The Impact of Student-Teacher Policy Perception on Employment Intentions in Rural Schools for Educational Sustainable Development Based on Push–Pull Theory: An Empirical Study from China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

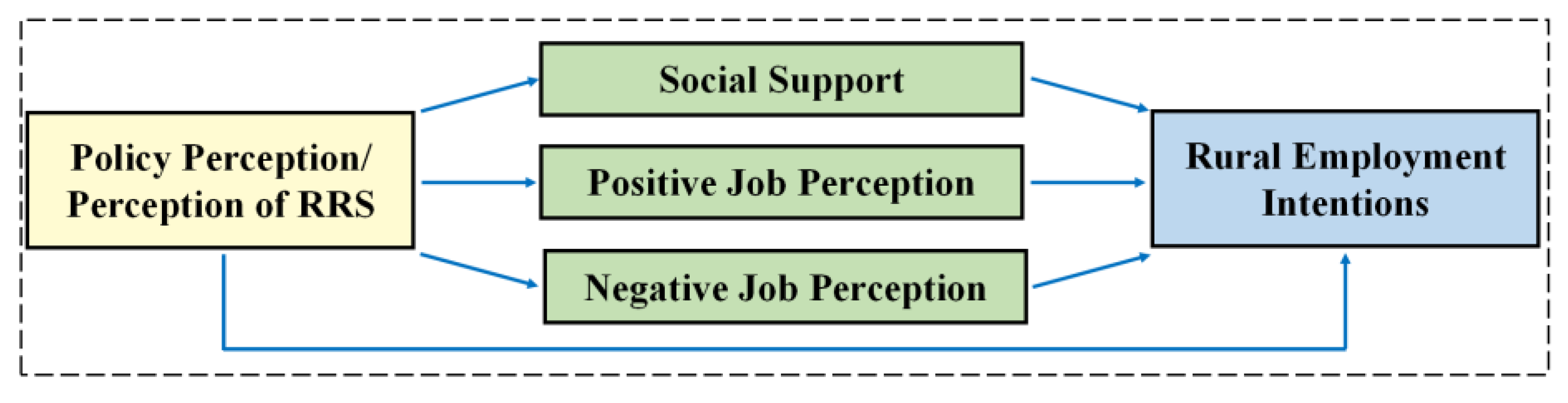

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Policy Perception and Rural Employment Intentions

2.2. Social Support

2.3. Job Perception

3. Research Design

3.1. Data Collection and Analysis

3.2. Sampling

3.3. Reliability

3.4. Validity

4. Results

4.1. Status Quo of Chinese Student-Teacher Perception of the Supporting Policy and Intentions to Teach in Rural Schools

4.2. Correlations between Factors That Influence Student-Teacher Rural Employment Intentions

4.3. Effects of Perception of RRS on Rural Employment Intentions

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aaronson, D.; Barrow, L.; Sander, W. Teachers and student achievement in the Chicago public high schools. J. Labor. Econ. 2007, 25, 95–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chetty, R.; Friedman, J.N.; Rockoff, J.E. Measuring the impacts of teachers II: Teacher value-added and student outcomes in adulthood. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 2633–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bertschy, F.; Künzli, C.; Lehmann, M. Teachers’ Competencies for the Implementation of Educational Offers in the Field of Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2013, 5, 5067–5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Indicators of Successful Teacher Recruitment and Retention in Oklahoma Rural Schools. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED576669 (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- Monk, D.H. Recruiting and Retaining High-Quality Teachers in Rural Areas. Future Child. 2007, 17, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanushek, E.A.; Kain, J.F.; Rivkin, S.G. Why public schools lose teachers. J. Hum. Resour. 2004, 39, 326–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeb, S.; Kalogrides, D.; Béteille, T. Effective schools: Teacher hiring, assignment, development, and retention. Educ. Financ. Policy 2012, 7, 269–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, H.; Cheng, X.; Cui, L. Progress or stagnation: Academic assessments for sustainable education in rural china. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X. Becoming a teacher in rural areas: How curriculum influences government-contracted pre-service physics teachers’ motivation. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 94, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the State Council. China Releases Five-Year Plan on Rural Vitalization Strategy. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2018-09/26/content_5325534.htm (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- Xue, E.; Li, J.; Li, X. Sustainable development of education in rural areas for rural revitalization in china: A comprehensive policy circle analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 2018 Central, No. 1 Document Fully Deploys and Implements the Rural Revitalization Strategy- Give Priority to the Development of Rural Education, Build a Strong Rural Teacher Team. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/gzdt_gzdt/s5987/201802/t20180205_326624.html (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- Arco, I.D.; Ramos-Pla, A.; Zsembinszki, G.; Gracia, A.D.; Cabeza, L.F. Implementing sdgs to a sustainable rural village development from community empowerment: Linking energy, education, innovation, and research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Faircheallaigh, C. Public participation and environmental impact assessment: Purposes, implications, and lessons for public policy making. Environ. Impact. Asses. 2010, 30, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, S.; Sives, A.; Morgan, W.J. The impact of international teacher migration on schooling in developing countries—The case of Southern Africa. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2006, 4, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, C. Uneven policy implementation in rural China. China. J. 2011, 65, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Walker, A. How principals promote and understand teacher development under curriculum reform in China. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Edu. 2013, 41, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, M.; Rozelle, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Luo, R.; Shi, Y. Conducting influential impact evaluations in China: The experience of the Rural Education Action Project. J. Dev. Effect. 2011, 3, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.J. Rural and urban differences in student achievement in science and mathematics: A multilevel analysis. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 1998, 9, 386–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y. Effects of free compulsory education on rural well-being in China. Asian-Pac. Econ. Lit. 2020, 34, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glewwe, P.; Muralidharan, K. Improving Education Outcomes in Developing Countries: Evidence, Knowledge Gaps, and Policy Implications; Elsevier Besloten Vennootschap: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, D.; Guo, H.D. Analysis of factors affecting college students’ will to work in rural areas: An empirical study based on a survey of students in Zhejiang province. J. Northwest A F Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2008, 11, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.; Liu, S. The influencing factors of college students’ rural employment intention in the context of the rural revitalization strategy. J. High. Educ-UK. 2019, 40, 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, H.S.; Taylor, S.F.; James, Y.S. “Migrating” to new service providers: Toward a unifying framework of consumers’ switching behaviors. J. Acad. Mark. Sci 2005, 33, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, B. Paradigms in migration research: Exploring “moorings” as a schema. Prog. Hum. Geog. 1995, 19, 504–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lengerke, T.V.; Vinck, J.; Rütten, A.; Reitmeir, P.; Abel, T.; Kannas, L.; Lüschen, G.; Diaz, J.A.R.; Zee, J.V.D. Health policy perception and health behaviours: A multilevel analysis and implications for public health psychology. J. Health Psychol. 2004, 9, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marshall, N.A. Can policy perception influence social resilience to policy change? Fish. Res. 2007, 86, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhe, C.; Guo-Hong, C. The influence of green technology cognition in adoption behavior: On the consideration of green innovation policy perception’s moderating effect. J. Discret. Math. Sci. Cryptogr. 2017, 20, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.C.; Fu, W.D. An empirical study on the employment intention and its influencing factors of the first free-tuition undergraduates of the six ministerial normal universities in China. J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2011, 50, 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Uygun, R.; Kasimoglu, M. The emergence of entrepreneurial intentions in indigenous entrepreneurs: The role of personal background on the antecedents of intentions. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 8, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Otache, I. Entrepreneurship education and undergraduate students’self- and paid-employment intentions: A conceptual framework. Educ. Train. 2019, 61, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. The Impacts of Self—leadership and Participation in Job Search Supporting Programs on Employment Intention of Senior Students in University: The Mediating Effect of Career Motivation. Korean Bus. Educ. Rev. 2015, 30, 377–405. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.S.; Tilse, C.; Wilson, J.; Tuckett, A.; Newcombe, P. Perceptions and employment intentions among aged care nurses and nursing assistants from diverse cultural backgrounds: A qualitative interview study. J. Aging. Stud. 2015, 35, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, P.; Hudson, S. Changing preservice teachers’ attitudes for teaching in rural schools. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2008, 33, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brill, S.; McCartney, A. Stopping the revolving door: Increasing teacher retention. Politics Policy 2008, 36, 750–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom. Med. 1976, 38, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thoits, P.A. Conceptual, methodological, and theoretical problems in studying social support as a buffer against life stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1982, 23, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, S. Can self-efficacy mediate between knowledge of policy, school support and teacher attitudes towards inclusive education. PloS ONE 2021, 16, e0262625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M.; Roslan, S.; Al-Amin, A.Q.; Filho, W.L. Does GATS’ Influence on Private University Sector’s Growth Ensure ESD or Develop City ‘Sustainability Crisis’—Policy Framework to Respond COP21. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muschalla, B. Mental health problem or workplace problem or something else: What contributes to work perception. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Ngo, H.; Playford, D. Gender equity at last: A national study of medical students considering a career in rural medicine. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliesi, K. The Consequences of Emotional Labor: Effects on Work Stress, Job Satisfaction, and Well-Being. Motiv. Emotion. 1999, 23, 125–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T. Study on the Influencing Factors and Countermeasures of Rural College Students’ Willingness to Return to Their Hometowns for Employment and Entrepreneurship. Master’s Thesis, Hubei University, Wuhan, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar, J.J. Structural Equation Modelling: Application for Research and Practice (with AMOS and R); Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kopalle, P.K.; Lehmann, D.R. Alpha inflation? The impact of eliminating scale items on Cronbach’s alpha. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1997, 70, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S. Tests of significance in factor analysis. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1950, 3, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufteros, X.A. Testing a model of pull production: A paradigm for manufacturing research using structural equation modeling. J. Oper. Manag. 1999, 17, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M.; Miles, J.N. Effects of sample size, model specification and factor loadings on the GFI in confirmatory factor analysis. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 1998, 25, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Kraemer, K.L. Post-adoption variations in usage and value of e-business by organizations: Cross-country evidence from the retail industry. Inform. Syst. Res. 2005, 16, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, L.; Rashid, H. The mediating role of work-leisure conflict on job stress and retention of it professionals. Acad. Inf. Manag. Sci. J. 2010, 13, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.L.; Ye, B.J. Mediating effect analysis: Methods and model development. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wen, Z.; Hau, K.T. Mediation effects in 2-1-1 multilevel model: Evaluation of alternative estimation methods. Struct. Equ. Modeling 2019, 26, 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Cox, M.G. Commentary on “Mediation analysis and categorical variables: The final frontier” by Dawn Iacobucci. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 600–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.W.; Zhang, Y.J.; Feng, W.B. Difficulties and Breakthroughs in Strengthening the Ranks of Rural Teachers:Based on the Survey of Rural Teachers’ Perception and Attitude Towards Policy. J. Chin. Soc. Educ. 2020, 6, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.P. It’s not only work and pay: The moderation role of teachers’ professional identity on their job satisfaction in rural China. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2020, 15, 971–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Li, X.Q. Policy’s perception and the college graduates’ grass-root employment: Based on the Bandura’s reciprocal determinism. Peking Univ. Educ. Rev. 2015, 13, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Beckley, T.M. Community stability and the relationship between economic and social well-being in forest-dependent communities. Soc. Nature Resour. 1995, 8, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Y. Research on the Implementation of Grassroots Employment Policy for College Students in Local Colleges and Universities. Master’s Thesis, Sichuan Normal University, Chengdu, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schepens, A.; Aelterman, A.; Vlerick, P. Student teachers’ professional identity formation: Between being born as a teacher and becoming one. Educ. Stud-UK 2009, 35, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranik, L.E.; Roling, E.A.; Eby, L.T. Why does mentoring work? The role of perceived organizational support. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lamote, C.; Engels, N. The development of student-teachers’ professional identity. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2010, 33, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, T.; Pál, J. Science teachers’ satisfaction: Evidence from the PISA 2015 teacher survey. OECD Publ. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fiksenbaum, L.; Jeng, W.; Koyuncu, M.; Burke, R.J. Work hours, work intensity, satisfactions and psychological well-being among hotel managers in China. Cross. Cult. Manag. 2010, 17, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.J.; Zhang, L.; Miao, R.F.; Wang, M.Z. Changes and prospects of rural teacher compensation policy from the perspective of positive psychology. Psychiat. Danub. 2021, 33, S265–S266. [Google Scholar]

- Preparations for the 2022 National Master’s Degree Entrance Examination are Underway. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/gzdt_gzdt/s5987/202112/t20211222_589176.html (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- Xie, Y.; Hannum, E. Regional variation in earnings inequality in reform-era urban China. Am. J. Sociol. 1996, 101, 950–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, J.; White, S.; Lock, G. The Rural Practicum: Preparing a Quality Teacher Workforce for Rural and Regional Australia. J. Res. Rural Educ. 2013, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage | Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Year | ||||

| Male | 101 | 15.0% | Freshman | 129 | 19.1% |

| Female | 574 | 85.0% | Sophomore | 117 | 17.3% |

| One-child family | Junior | 152 | 22.5% | ||

| Yes | 175 | 25.9% | Senior | 65 | 9.60% |

| No | 500 | 74.1% | First-year graduate | 74 | 11.0% |

| High school elective courses | Second-year graduate | 68 | 10.1% | ||

| Science | 332 | 49.2% | Third-year graduate | 26 | 3.90% |

| Literature and history | 343 | 50.8% | Others | 44 | 6.50% |

| Academic qualifications | Census registration | ||||

| Undergraduate | 504 | 74.7% | Urban | 292 | 43.3% |

| Graduate | 171 | 25.3% | Rural | 383 | 56.7% |

| Variable | Dimension | α | Variable | Dimension | α | Variable | Dimension | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social support | Family Support | 0.851 | Positive job perception | Career Development | 0.671 | Negative job perception | Work Pressure | 0.643 |

| Classmate Support | Work Environment | Cost of Living | ||||||

| Friend Support | Promotion Opportunities | Total α | 0.729 |

| KMO Value | Bartlett’s Spherical Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate Chi-Square | Degree of Freedom | Significance | |

| 0.734 | 1753.266 | 28 | <0.001 |

| Model Fit Indices | Recommended Value | Actual Values (Modified) |

|---|---|---|

| GFI | >0.90 | 0.986 |

| AGFI | >0.90 | 0.968 |

| RMSEA | <0.08, good; <0.05, excellent | 0.047 |

| SRMR | <0.05 | 0.035 |

| NFI | >0.90 | 0.978 |

| TLI | >0.90 | 0.977 |

| CFI | >0.90 | 0.987 |

| IFI | >0.90 | 0.987 |

| CIMN/DF | 1–3 | 2.496 |

| PNFI | >0.50 | 0.559 |

| Variable | Dimension | FL | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social support | ①Family Support | 0.674 *** | 0.864 | 0.682 |

| ②Classmate Support | 0.903 *** | |||

| ③Friend Support | 0.881 *** | |||

| Positive job perception | ①Career Development | 0.686 *** | 0.795 | 0.566 |

| ②Working Environment | 0.838 *** | |||

| ③Promotion Opportunities | 0.724 *** | |||

| Negative job perception | ①Work Pressure | 0.973 *** | 0.724 | 0.593 |

| ② Cost of Living | 0.489 * |

| a | b | c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AVE | 0.682 | 0.566 | 0.593 |

| Social support | 0.826 | ||

| Positive job perception | 0.452 *** | 0.752 | |

| Negative job perception | 0.053 | 0.165 *** | 0.770 |

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation (SD) | Minimum | Maximum | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural employment intentions | 0.439 | 0.497 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.248 | −1.944 |

| Policy perception | 2.790 | 0.793 | 1.000 | 5.000 | −0.094 | −0.047 |

| Social support | 2.238 | 0.667 | 0.820 | 4.100 | −0.071 | −0.017 |

| Positive job perception | 2.497 | 0.610 | 0.990 | 3.990 | −0.299 | −0.188 |

| Negative job perception | 2.434 | 0.642 | 0.730 | 3.660 | −0.410 | −0.239 |

| Satisfaction with unpaid teaching | 3.257 | 0.667 | 1.000 | 5.000 | −0.347 | 0.971 |

| Variable | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural employment intentions | a | 1 | |||||||||||

| Policy perception | b | 0.165 *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Positive job perception | c | 0.296 *** | 0.173 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| Negative job perception | d | −0.025 | 0.082 * | 0.141 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| Social support | e | 0.484 *** | 0.152 *** | 0.409 *** | 0.036 | 1 | |||||||

| Unpaid teaching participation | f | 0.046 | 0.172 *** | −0.041 | 0.05 | 0.023 | 1 | ||||||

| Unpaid teaching satisfaction | g | 0.089 * | 0.209 *** | 0.016 | 0.079 * | 0.086 * | 0.971 *** | 1 | |||||

| Gender | h | −0.065 | −0.032 | −0.014 | −0.008 | −0.112 ** | 0.134 *** | 0.110 ** | 1 | ||||

| One-child family | i | 0.025 | −0.045 | 0.047 | −0.002 | 0.011 | −0.018 | −0.037 | 0.140 *** | 1 | |||

| Academic qualifications | j | 0.185 *** | 0.031 | 0.139 *** | −0.039 | 0.228 *** | −0.123 ** | −0.103 ** | −0.092 * | 0.052 | 1 | ||

| High school elective courses | k | −0.116 ** | 0.036 | −0.081 * | −0.035 | −0.093 * | 0.072 | 0.07 | 0.152 *** | −0.021 | −0.157 *** | 1 | |

| Census registration | l | 0.157 *** | 0.042 | 0.059 | 0.002 | 0.121 ** | 0.023 | 0.024 | 0.019 | 0.377 *** | −0.007 | −0.04 | l |

| Rural Employment Intentions | Rural Employment Intentions | Positive Job Perception | Negative Job Perception | Social Support | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non. Std. Coeff. (SE) | OR (SE) | Non. Std. Coeff. (SE) | OR (SE) | Non. Std. Coeff. (SE) | Std. Coeff. (SE) | Non. Std. Coeff. (SE) | Std. Coeff. (SE) | Non. Std. Coeff. (SE) | Std. Coeff. (SE) | |

| Policy perception | 0.352 ** | 1.422 ** | 0.269 * | 1.308 * | 0.112 *** | 0.146 *** | 0.047 | 0.058 | 0.078 * | 0.093 * |

| (0.111) | (0.158) | (0.125) | (0.163) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.032) | (0.032) | (0.031) | (0.031) | |

| Positive job perception | 0.532 ** | 1.702 ** | ||||||||

| (0.177) | (0.302) | |||||||||

| Negative job perception | −0.285 | 0.752 | ||||||||

| (0.152) | (0.114) | |||||||||

| Social support | 1.675 *** | 5.339 *** | ||||||||

| (0.192) | (1.022) | |||||||||

| Academic qualifications (Undergraduates as the standard) | ||||||||||

| Graduate | 0.894 *** | 2.445 *** | 0.489 * | 1.631 * | 0.146 ** | 0.104 ** | −0.077 | −0.052 | 0.310 *** | 0.202 *** |

| (0.206) | (0.502) | (0.231) | (0.378) | (0.053) | (0.053) | (0.058) | (0.058) | (0.056) | (0.056) | |

| Unpaid teaching participation (did not take part in unpaid teaching as the standard) | ||||||||||

| Unpaid Teaching | −3.112 *** | 0.0445 *** | −1.652 | 0.192 | −1.164 *** | −0.888 *** | −0.622 ** | −0.451 ** | −1.251 *** | −0.873 *** |

| (0.890) | (0.0396) | (1.032) | (0.198) | (0.205) | (0.205) | (0.224) | (0.224) | (0.218) | (0.218) | |

| Unpaid Teaching Satisfaction | 1.027 *** | 2.792 *** | 0.587 | 1.798 | 0.336 *** | 0.861 *** | 0.207 ** | 0.503 ** | 0.403 *** | 0.943 *** |

| (0.266) | (0.741) | (0.309) | (0.556) | (0.061) | (0.061) | (0.067) | (0.067) | (0.065) | (0.065) | |

| High school elective courses (Science and Engineering as the standard) | ||||||||||

| Literature and history | −0.395 * | 0.673 * | −0.367 | 0.693 | −0.083 | −0.068 | −0.061 | −0.048 | −0.070 | −0.053 |

| (0.169) | (0.114) | (0.189) | (0.131) | (0.046) | (0.046) | (0.050) | (0.050) | (0.049) | (0.049) | |

| Census registration (Urban as the standard) | ||||||||||

| Rural | 0.716 *** | 2.047 *** | 0.618 ** | 1.855 ** | 0.040 | 0.032 | −0.014 | −0.011 | 0.161 ** | 0.120 ** |

| (0.184) | (0.376) | (0.206) | (0.383) | (0.049) | (0.049) | (0.054) | (0.054) | (0.052) | (0.052) | |

| Gender (Male as the standard) | ||||||||||

| Female | −0.179 | 0.836 | −0.015 | 0.985 | 0.048 | 0.028 | −0.001 | −0.000 | −0.129 | −0.069 |

| (0.237) | (0.198) | (0.268) | (0.264) | (0.065) | (0.065) | (0.071) | (0.071) | (0.069) | (0.069) | |

| One child (One-child family as the standard) | ||||||||||

| Not one child | −0.120 | 0.887 | −0.152 | 0.859 | 0.064 | 0.046 | 0.024 | 0.017 | −0.018 | −0.012 |

| (0.211) | (0.187) | (0.237) | (0.204) | (0.056) | (0.056) | (0.062) | (0.062) | (0.060) | (0.060) | |

| Constant term | −1.973 *** | 0.139 *** | −5.995 *** | 0.00249 *** | 2.028 *** | 2.365 *** | 1.837 *** | |||

| (0.435) | (0.0606) | (0.785) | (0.00196) | (0.115) | (0.126) | (0.122) | ||||

| Pseudo R2/R2 | 0.0915 | 0.2439 | 0.099 | 0.025 | 0.148 | |||||

| adj. R2 | - | - | 0.088 | 0.014 | 0.138 | |||||

| F | 84.71 *** | 225.75 *** | 9.165 *** | 2.178 * | 14.459 *** | |||||

| Number | 675 | 675 | 675 | 675 | 675 | |||||

| Path | Point EstimationEffect Value(Standard Error) | 95% CIs | Mediation Effect (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non. Std. Coeff. | Std. Coeff /OR | Non. Std. Coeff. | |||

| Policy perception→Rural employment intentions | c | 0.352 ** (0.111) | 1.422 ** (0.158) | ||

| Policy perception → Positive job perception | a1 | 0.112 *** (0.029) | 0.146 *** (0.029) | ||

| Positive job perception → Rural employment intentions | b1 | 0.532 ** (0.177) | 1.702 ** (0.302) | ||

| Policy perception → Negative job perception | a2 | 0.047 (0.032) | 0.058 (0.032) | ||

| Negative job perception → Rural employment intentions | b2 | 0.285 (0.152) | 0.752 (0.114) | ||

| Policy perception → Social support | a3 | 0.078 * (0.031) | 0.093 * (0.031) | ||

| Social support → Rural employment intentions | b3 | 1.675 *** (0.192) | 5.339 *** (1.022) | ||

| Policy perception → Rural employment intentions | c’ | 0.269 * (0.125) | 1.308 * (0.163) | ||

| Policy perception → Positive job perception → Rural employment intentions | a1*b1 | 0.060 (0.026) | - | [0.017, 0.116] | 17.04% |

| Policy perception → Negative job perception → Rural employment intentions | a2*b2 | −0.013 (0.013) | - | [−0.043, 0.005] | - |

| Policy perception → Social support → Rural employment intentions | a3*b3 | 0.131 (0.054) | - | [0.028, 0.242] | 37.21% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, S.; Wang, R.; Wang, T.; Zhou, W. The Impact of Student-Teacher Policy Perception on Employment Intentions in Rural Schools for Educational Sustainable Development Based on Push–Pull Theory: An Empirical Study from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116639

Chen S, Wang R, Wang T, Zhou W. The Impact of Student-Teacher Policy Perception on Employment Intentions in Rural Schools for Educational Sustainable Development Based on Push–Pull Theory: An Empirical Study from China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116639

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Siyu, Ran Wang, Tingting Wang, and Wenxian Zhou. 2022. "The Impact of Student-Teacher Policy Perception on Employment Intentions in Rural Schools for Educational Sustainable Development Based on Push–Pull Theory: An Empirical Study from China" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116639

APA StyleChen, S., Wang, R., Wang, T., & Zhou, W. (2022). The Impact of Student-Teacher Policy Perception on Employment Intentions in Rural Schools for Educational Sustainable Development Based on Push–Pull Theory: An Empirical Study from China. Sustainability, 14(11), 6639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116639