Exploiting Marketing Methods for Increasing Participation and Engagement in Sustainable Mobility Planning

Abstract

:1. Introduction

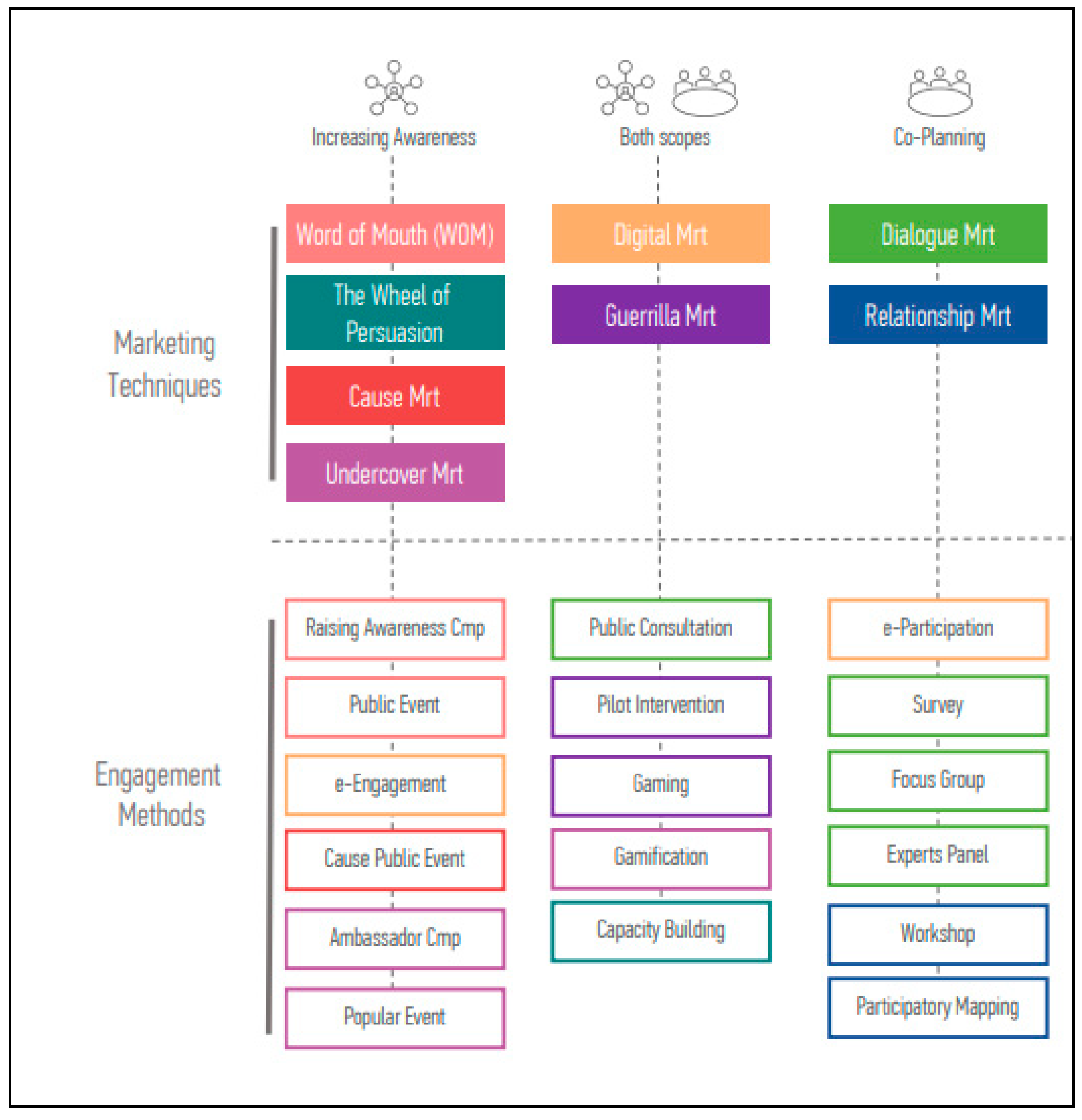

- Awareness, which refers to all techniques and methods used for informing, raising awareness among, and educating the public, with the ultimate goal of adopting new behavioral patterns that favor sustainable mobility.

- Collaboration and co-design, which refers to all techniques and methods exploited for promoting collaboration and active public participation in the design process [26].

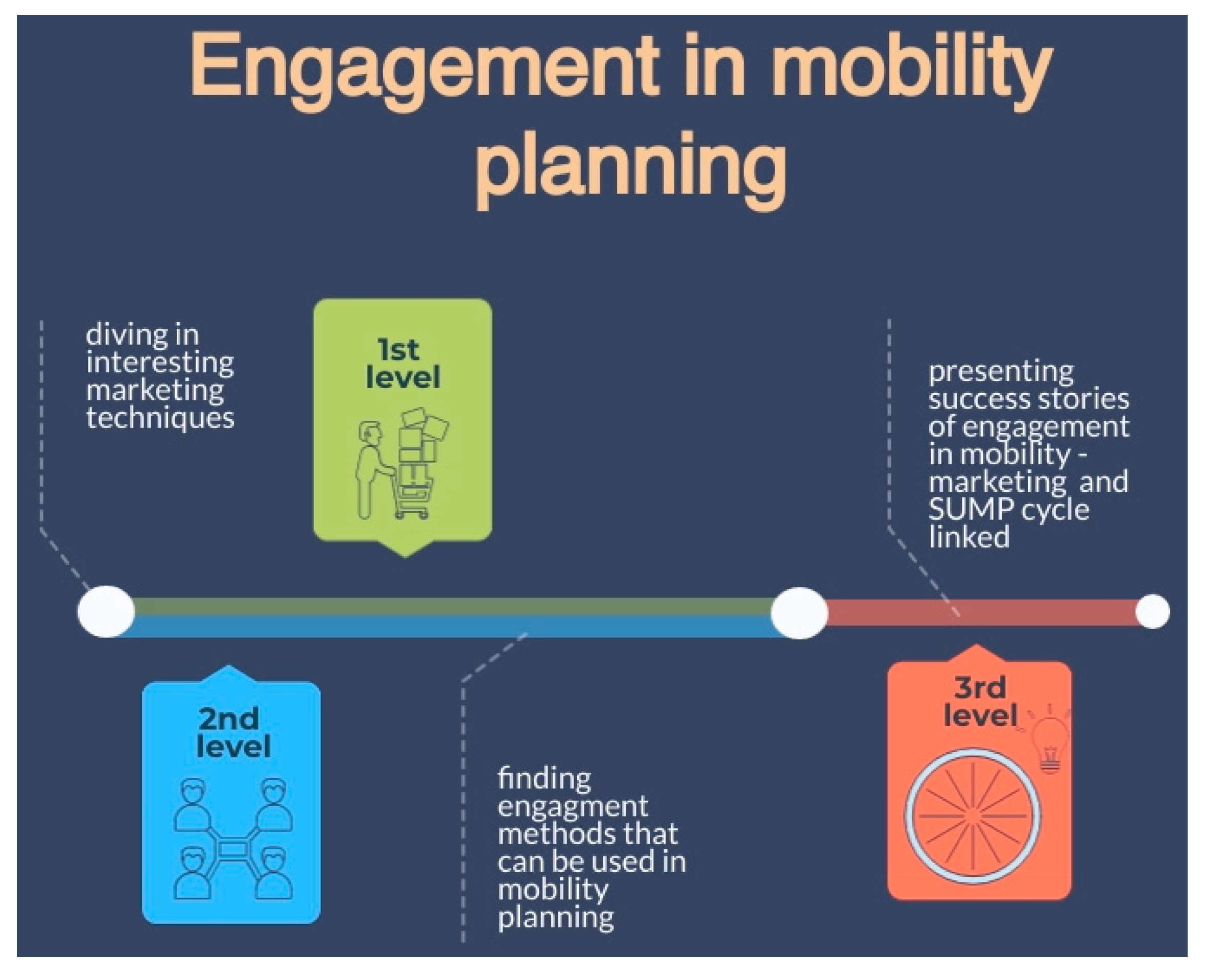

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. First and Second Levels of Review; Marketing Techniques and Methods for Increasing Engagement Levels

2.1.1. Word-of-Mouth Communication

- Rapid diffusion of information,

- Attracting the public interest through interactive visualized elements,

- Use of mass communication channels/wide range of audience coverage,

- Use of simple and targeted verbal content.

2.1.2. Cause Marketing

- Focuses on raising public awareness around a topic, while combining relevant activities or ideas that can be attributed to the topic under investigation.

- Is usually used by non-profit organizations.

- Offers the opportunity to engage the public, not only rationally but also emotionally, through the promotion of moral values and new patterns of behavior.

- Focuses on the emotional interaction of the audience, emphasizing the sense of social responsibility.

2.1.3. Digital Marketing

2.1.4. Dialogue Marketing

- Creating trust with the public;

- Offering simple and targeted thematic communication;

- Creating safe spaces for the exchange of views and ideas, encouraging diversity.

2.1.5. Relationship Marketing

- Target group interaction: Targeting a specific audience using social media to create dialogue.

- Creation of centers of influence: Cooperation with key actors for the creation of “cells” of influence.

- Co-planning: Use of targeted methods aimed at the cooperation of citizens and stakeholders in joint decision-making.

2.1.6. The Wheel of Persuasion

2.1.7. Guerilla Marketing

- Low-cost, low-budget needs;

- Inventiveness and creativity, e.g., in the use of alternative ways of interacting with the public;

- Intense interaction with the public;

- Use of digital channels to attract the target group and create an original experience [43]; augmented reality and virtual reality are the most modern aspects injected into guerilla marketing methods.

2.1.8. Undercover Marketing

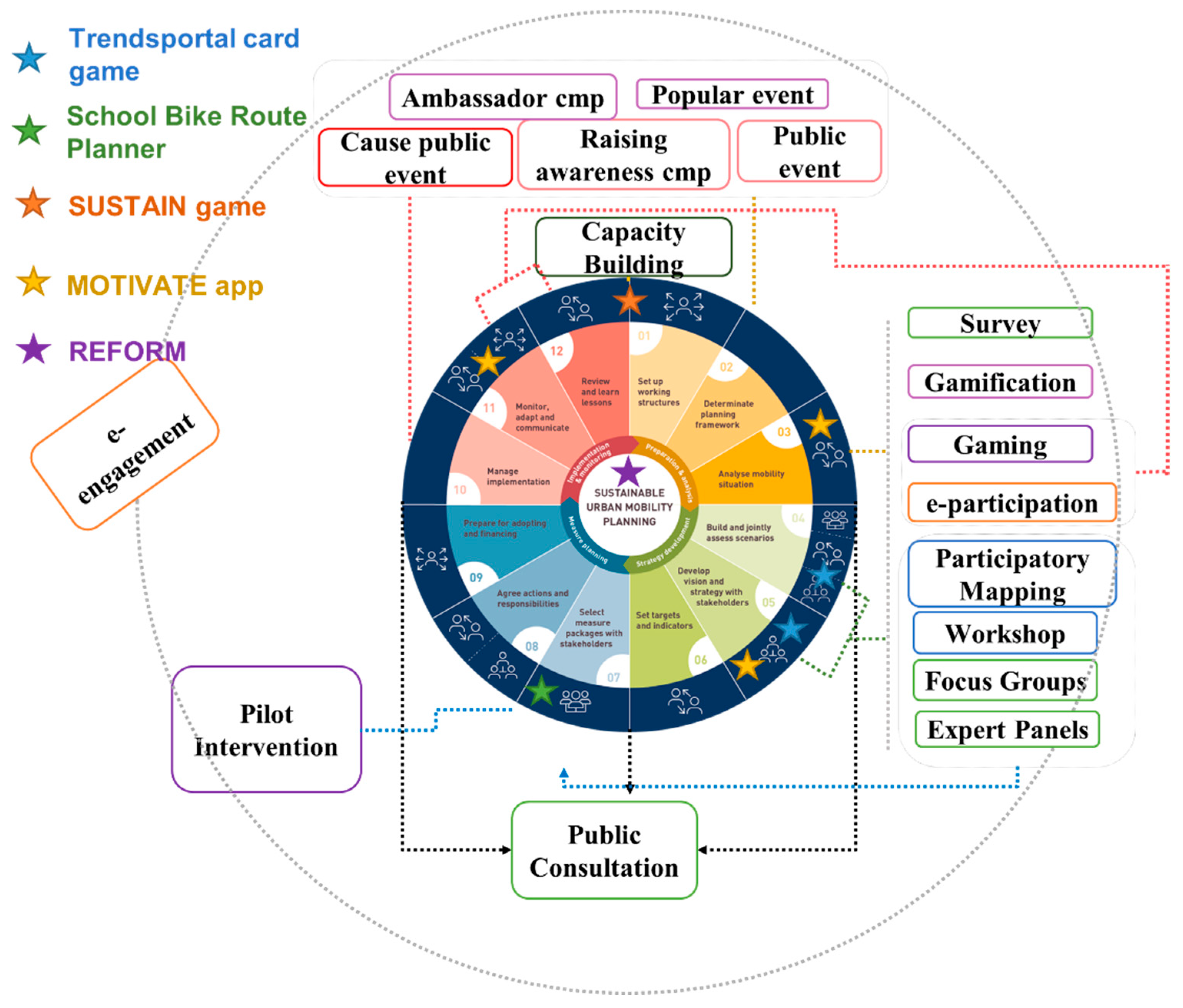

2.2. Third Level of Review; Success Stories in Engagement throughout the SUMP Cycle

2.2.1. MOTIVATE App: A Crowd-Sourcing and Interactive Learning Environment

- Support the participatory approach of the decision-making process;

- Provide insight into real travelers’ needs;

- Increase travelers’ interest in the mobility planning process;

- Transform travelers’ into active agents of sustainable mobility adoption;

- Raise awareness in terms of sustainable mobility.

2.2.2. Trendsportal Card Game; a Serious Game Facilitating Sustainable Mobility Vision Co-Creation

2.2.3. School Bike Route Planner; Co-Designing the Way to School by Bike

2.2.4. Placing Students in the Role of Decision Makers of Tomorrow, the Interactive SUSTAIN Erasmus + Project Sustainability Awareness Game

2.2.5. REFORM: Fostering Regional Cooperation and Capacity Building for SUMPs

- Improve the average level of knowledge among city officers and technicians about SUMPs;

- Raise awareness at regional and municipal levels about the scope and content of SUMPs;

- Enhance the planning capacities of regions and municipalities in SUMP development;

- Inculcate the SUMP principle of cross-sectoral and cross-municipal planning.

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forester, J. The Deliberative Practitioner: Encouraging Participatory Planning Processes; Mit Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.W. A theoretical basis for participatory planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigea, A. Theory and Methods of Participatory Design; Association of Greek Academic Libraries: Athens, Greece, 2015; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11419/5428 (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Merton, R.K. The Focused Interview and Focus Groups: Continuities and Discontinuities. Public Opin. Q. 1987, 51, 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.A. Moderating Focus Groups (Vol. 4); Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, C.; Kasemir, B.; Stoll-Kleemann, S.; Schibli, D.; Dahinden, U. Climate change and the voice of the public. Integr. Assess. 2000, 1, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, J. Focusing on the Focus Group. In Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2005; Chapter 8; pp. 116–132. [Google Scholar]

- Machina, M.J. Choice Under Uncertainty: Problems Solved and Unsolved. J. Econ. Perspect. 1987, 1, 121–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stratigea, A.; Giaoutzi, M. Linking global to regional scenarios in foresight. Futures 2012, 44, 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.G.; Dowlatabadi, H. Learning from integrated assessment of climate change. Clim. Chang. 1996, 34, 337–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmans, J. Methods for IA: The challenges and opportunities ahead. Environ. Model. Assess. 1998, 3, 155–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.; Wales, C. The Theory and Practice of Citizens’ Juries. Policy Politics Stud. Local Gov. Its Serv. 1999, 27, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishkin, J.J. The Voice of the People, Public Opinion and Democracy; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, J. Collaboration and Consensus. Town Ctry. Plan. 1998, 67, 111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, P. Critical Citizens; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, B. Citizens’ Engagement in Policymaking and the Design of Public Services; Parliamentary Library: Canberra, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Myrovali, G.; Tsaples, G.; Morfoulaki, M.; Aifadopoulou, G.; Papathanasiou, J. An Interactive Learning Environment Based on System Dynamics Methodology for Sustainable Mobility Challenges Communication & Citizens’ Engagement. In Decision Support Systems VIII: Sustainable Data-Driven and Evidence-Based Decision Support. ICDSST 2018; Dargam, F., Delias, P., Linden, I., Mareschal, B., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 313, pp. 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobos, A.; Jenei, A. Citizen Engagement as a Learning Experience. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 93, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bickerstaff, K.; Walker, G.P. Participatory Local Governance and Transport Planning. Environ. Plan. 2001, 33, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, C.; Richardson, T. Placing the public in integrated transport planning. Transp. Policy 2001, 8, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrovali, G.; Morfoulaki, M.; Vassilantonakis, B.-M.; Mpoutovinas, A.; Kotoula, K.M. Travelers-led Innovation in Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans. Period. Polytech. Transp. Eng. 2019, 48, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, P.; Porębska, A. Towards a Revised Framework for Participatory Planning in the Context of Risk. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, C.; Procentese, F.; Baldi, S. Participatory Planning and Community Development: An E-Learning Training Program. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2009, 38, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupprecht Consult (Ed.) Guidelines for Developing and Implementing a Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan, 2nd ed.; Rupprecht Consult Forschung & Beratung GmbH: Koln, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- e-smartec Project Interreg Europe 2014–2020. Del. Handbook for Success Tips on Marketing Techniques. 2020. Available online: https://projects2014-2020.interregeurope.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/tx_tevprojects/library/file_1611912931.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Levy, Y.; Ellis, T.J. A Systems Approach to Conduct an Effective Literature Review in Support of Information Systems Research. Inf. Sci. Int. J. Emerg. Transdiscipl. 2006, 9, 181–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whitnell, S. Successful Interventions with Hard to Reach Groups; Health and Safety Commission: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, M.; Lopez, C.; Molina, A. An integrated model of social media brand engagement. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 96, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopjani, L.; Stier, J.J.; Ritzén, S.; Hesselgren, M.; Georén, P. Involving users and user roles in the transition to sustainable mobility systems: The case of light electric vehicle sharing in Sweden. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 71, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, L.A.; Burkholder, G.J.; Morad, O.A.; Marsh, C. Computer-based technology and student engagement: A critical review of the literature. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2017, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meiners, N.H.; Schwarting, U.; Seeberger, B. The Renaissance of Word-of-Mouth Marketing: A New Standard in Twenty-First Century Marketing Management?! Int. J. Econ. Sci. Appl. Res. 2010, 3, 79. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, B.; Huba, J. Creating Customer Evangelists: How Loyal Customers Become a Volunteer Sales Force; Dearborn Trade Publishing: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- e-smartec Project Interreg Europe 2014–2020. H ελληνική εκδοχή του e-smartec Training Material, 2021. 2020. Available online: https://projects2014-2020.interregeurope.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/tx_tevprojects/library/file_1618577997.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Ng, S.; David, M.E.; Dagger, T.S. Generating positive word-of-mouth in the service experience. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2011, 21, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljas, A.E.M.; Walters, K.; Jovicic, A.; Iliffe, S.; Manthorpe, J.; Goodman, C.; Kharicha, K. Strategies to improve engagement of ‘hard to reach’ older people in research on health promotion: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, S.M.; Alcorn, D.S. Cause marketing: A new direction in the marketing of corporate responsibility. J. Consum. Mark. 1991, 8, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffey, D.; Ellis-Chadwick, F.; Mayer, R.; Johnston, K. Internet Marketing: Strategy, Implementation and Practice; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Abeza, G.; O’Reilly, N.; Reid, I. Relationship Marketing and Social Media in Sport. Int. J. Sport Commun. 2013, 6, 120–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightbody, R. ‘Hard to Reach’or ‘Easy to Ignore’? Promoting Equality in Community Engagement. 2017. Available online: https://researchonline.gcu.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/27037627/WWSHardToReachOrEasyToIgnoreEvidenceReview.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Funkhouser, G.R.; Parker, R. An Action-Based Theory of Persuasion in Marketing. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 1999, 7, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, J.C. Guerrilla Marketing; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Behal, V.; Sareen, S. Guerilla marketing: A low cost marketing strategy. Int. J. Manag. Res. Bus. Strategy 2014, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Armenia, S.; Ciobanu, N.; Kulakowska, M.; Myrovali, G.; Papathanasiou, J.; Pompei, A.; Tsaples, G.; Tsironis, L. An Innovative Game-Based Approach for Teaching Urban Sustainability. Balk. Reg. Conf. Eng. Bus. Educ. 2019, 3, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- e-smartec Project Interreg Europe 2014–2020. Del. State-of-the Art on Marketing Techniques for Citizens’ Engagement in e-smartec Regions. 2020. Available online: https://projects2014-2020.interregeurope.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/tx_tevprojects/library/file_1618911855.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Solińska-Nowak, A. Sustain, How to Learn Urban Sustainability through a Simulation. 2020. Available online: https://socialsimulations.org/sustain/ (accessed on 11 April 2021).

| MT | PM | Definition/Key Characteristics/Types or Tools | Participants | SUMP Cycle Phase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizens | Stakeholders | ||||

| Digital Marketing | e-Engagement | e-Engagement in the form of online campaigning is similar to the method “Raising Awareness Campaign” but focuses on web-based channels and digital tools. Key characteristics:

| All citizens | - | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Digital Marketing | e-Participation | e-Participation has been defined as “the utilization of information and communication technology in order to extend and deepen citizen’s participation.” Crowd-sourcing is an online citizen engagement method that enables active participation in decision-making or planning processes. This method is basically an open invitation to every citizen willing to participate in particular issues, by commenting and sharing insights or ideas, via a free-access online platform. Key characteristics:

| All citizens | Key stakeholders | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Dialogue Marketing | Surveys | A survey is a method used for the collection of information or opinions/preferences on a specific topic of interest from a predefined group of respondents. Key characteristics:

| All citizens | Key stakeholders | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Dialogue Marketing | Public Consultation | Public consultation is a regulatory process that invites citizens and stakeholders to provide their views and feedback on the current stage of the project. Key characteristics:

| Randomly selected citizens | Experts, stakeholders, and politicians | 1, 2, 3 |

| Dialogue Marketing | Focus Group | A focus group is a structured discussion among a small group of participants, facilitated by a skilled moderator. This method is designed to obtain insights, ideas, and opinions from the participants on a specific topic. Key characteristics:

| All citizens | All types of stakeholders | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Dialogue Marketing | Expert Panel | An expert panel is a specialized discussion among a variety of experts and active actors in a project. Its objective is to synthesize the input of experts from different disciplines on a certain topic and produce a vision or recommendations for future possibilities and needs for the selected topic/project. Key characteristics:

| - | Experts from many disciplines | 1, 2, 3 |

| MT | PM | Definition/Key Characteristics/Types or Tools | Participants | SUMP Cycle Phase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizens | Stakeholders | ||||

| Guerrilla Marketing | Pilot Interventions | Pilot intervention is an approach where physical interventions of a temporary character are implemented on a trial basis, similar to a prototype, leading toward a more permanent transformation in the future. Key characteristics:

| All citizens | Key stakeholders | 4 |

| Guerrilla Marketing | Gaming | The gaming approach can be described as a chameleon method. This approach masks learning technologies and pedagogical principles in a game-based environment with the objective of engaging and motivating participants by offering entertainment and joy. Types:

| All citizens | All types of stakeholders | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Undercover Marketing | Gamification | The gamification method has been broadly defined as the use of game elements in non-game contexts. It refers to an instructional approach with the aim to increase engagement, motivation, and participation. Key characteristics:

| All citizens | Key stakeholders | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Undercover Marketing | Ambassador Campaign | The ambassador campaign method is a form of indirect promotion by collaborating with important public figures (celebrities, opinion-leaders, influencers, etc.). Key characteristics:

| All citizens | - | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Undercover Marketing | Popular Events | The popular event method is an indirect form of promotion where the popularity of a current event is capitalized on in order to gather attention for an additional issue. The term “popular” refers to all types of events and happenings that are well established and known to the public, from major sports events and games to cultural events and festivals. Key characteristics:

| All citizens | - | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| MT | PM | Definition/Key Characteristics/Types or Tools | Participants | SUMP Cycle Phase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizens | Stakeholders | ||||

| Word of Mouth | Raising Awareness Campaign | A promotional campaign that uses several tools in order to reach as many individuals as possible. Key characteristics:

| All citizens | Relevant stakeholders | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Cause Marketing | |||||

| Word of Mouth | Public Events | A public event aims to raise awareness as a means of stimulating interest and creating publicity. Such events provide to the organizers the opportunities to inform the public about a priority issue, a specific milestone, or the entire project. Local individuals and organizations are invited to participate in them. Key characteristics:

| All citizens | Interdisciplinary group of stakeholders | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Cause Marketing | |||||

| MT | PM | Definition/ Key Characteristics/Types or Tools | Participants | SUMP Cycle Phase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizens | Stakeholders | ||||

| Relationship Marketing | Workshop | A workshop is an intensive planning session where citizens, stakeholders, and experts collaborate on the development of a shared vision. It is a face-to-face process designed to bring people from various sub-groups of society into a consensus by providing adequate information to all participants and equal opportunity to contribute in co-creating a vision/proposal. Key characteristics:

| Citizens from various sub-groups of society | All types of stakeholders | 1, 2, 3 |

| Relationship Marketing | Participatory Mapping | Participatory mapping, also called community-based mapping, is a general term used to define a method that combines the tools of modern cartography with participatory approaches in order to represent the spatial knowledge of local communities. Key characteristics:

| All citizens | All types of stakeholders | 1, 2 |

| The wheel of Persuasion | Capacity Building | Capacity building is a method that develops further a certain range of skills and competencies of the participants. Key characteristics:

| Selected group of citizens | All types of stakeholders | 1, 4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morfoulaki, M.; Myrovali, G.; Chatziathanasiou, M. Exploiting Marketing Methods for Increasing Participation and Engagement in Sustainable Mobility Planning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4820. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084820

Morfoulaki M, Myrovali G, Chatziathanasiou M. Exploiting Marketing Methods for Increasing Participation and Engagement in Sustainable Mobility Planning. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4820. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084820

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorfoulaki, Maria, Glykeria Myrovali, and Maria Chatziathanasiou. 2022. "Exploiting Marketing Methods for Increasing Participation and Engagement in Sustainable Mobility Planning" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4820. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084820

APA StyleMorfoulaki, M., Myrovali, G., & Chatziathanasiou, M. (2022). Exploiting Marketing Methods for Increasing Participation and Engagement in Sustainable Mobility Planning. Sustainability, 14(8), 4820. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084820