Abstract

The debate on IEQ (Indoor Environmental Quality), with a focus on the healthiness of the built environment and its possible influence on the natural environment, has been a relevant topic for a decade. This interest has expanded to the quality of building technologies, specifically their performances and environmental effects. The objectives set by the 2030 Agenda have led to overcome the idea that sustainability is only related to environment; instead, a holistic vision aimed at human health has been affirmed (objective 3). The period marked by the Covid19 emergency contributed to strengthen the need for human well-being, as the “quarantine” made us observe our living spaces, reflecting on quality that we ourselves perceive. There is the need for a transition from a “Green” approach to architecture, toward a “Human Centered” approach with a user-centered design. The paper focuses on the factors that can affect users’ well-being in their living space, by comparing the most common building environmental certifications (LEED, BREEAM) with WELL, a tool designed to verify the level of users’ health and well-being. Specifically, the objective is to verify, within these methodologies, the presence and possible weight of the indicators that define a quality living space according to the user’s perception.

1. Introduction

Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) defines the level of compliance of a set of building performances to requirements related to users’ needs. IEQ evaluation is a complex topic, because of the immaterial (psychological) and material (physical and environmental) characteristics involved. This topic has attracted an increasing interest: as a result, building regulations are now focused on users’ health, in addition to the well-known aspects related to energy saving. The last European Directive on building energy performance (EPBD 2018/844) reports the concept of “indoor climate” and describes the elements that influence it; however, it does not include specific indicators, which would contribute to the creation of healthy and comfortable indoor environments [1]. Instead, tool-measurable indicators are defined by the UNI EN 16798-1:2019 standard [2]: the latter proposes an evaluation of building energy performance in relation to indoor air quality, thermal environment, lighting, and acoustics. In particular, the standard measures IEQ as a function of local discomfort factors (air currents, asymmetry of the heating surface, temperature differences of vertical air currents, floor surface temperature, etc.).

Albeit recent studies have led to an improved definition of these standards, by introducing more efficient parameters and acceptable ranges, other research works have shown that, even when all the indoor parameters fall within the correct ranges, not all the users of the buildings are satisfied about their environment. In addition to individual variability, the reason could be related to the presence of non-environmental factors with an influence on perception, in addition to physical conditions [3]. IEQ is related to the concept of social sustainability in a human-centered vision, determined by users’ needs and by users’ environmental perception. Perception depends on time and on users’ adaptability to the environment [4] and can depend on countless factors (education level, psycho-social conditions at the workplace, urban context, age, birthplace, etc.). Hence, the possibility to control indoor environments improves general living quality [5].

Designing for an “average person” means to satisfy only 50% of the users; then, as in Design for All, the key is the control of elements. Architecture can truly become “for all” if space can be controlled as each one pleases. This concept implies overcoming the exclusively “green” architectural approach based on environmental sustainability, toward an approach that integrates the holistic “person-environment” concept, providing users with an active role in the management of the individual living environment. This is also confirmed by a large literature, as this topic is discussed in several research fields. In fact, the relation between building and health has been discussed when the World Health Organization created the term “Sick Building Syndrome” (SBS), relating users’ sensorial discomfort to chemical compounds in indoor air, and in the materials used. As a consequence, ASHRAE coded the IAQ (Indoor Air Quality) standard, which defined an acceptable CO2 level and a recommended air exchange rate. In this framework, some research works associate unsuitable thermo-hygrometric conditions with an increase in the risk of lung diseases in residential buildings, and with a drastic reduction in the attention level in workplaces [6]. A further indication from the field of Design is represented by the recent approach “User Experience (UX)”, a significant branch of the Human-Centered Design (HCD) method, which provides a system of techniques aimed to the evaluation of the emotional dimension [7]. In architecture, UX can be applied to the spatial experiences (residential, working spaces, etc.), to smart environments (the so-called ubiquitous computing), to driving, orientation and safety systems, and to the building-nature interaction. The starting point for a UX Designer is to ask why, how and which the best product for their user should be. The design process starts with a research phase to collect data, understand the user’s fundamental needs, perform user interviews, and set usability goals for the product within the project–in architecture, that corresponds to habitability. Recent survey methodologies have been successfully used in the co-design between designers and users, as a partial substitution for the measurement of parameters and aspects related to the use experience. However, the test of a single product is certainly simpler and more economical, than the comfort assessment of an indoor environment, with multiple elements and variables.

In the architectural field, the definition of quality has involved the entrepreneurial field and market strategies for building sale as well. In fact, enterprises compete in a global market; hence, they have started to make a voluntary use of building performance certifications. Over years, these have taken an increasingly crucial role as a guarantee of reliability and specificity of the performed work [8]. In the certifications proposed in the last decade, IEQ has been related to building projects with a high environmental sustainability, and to their realization in the building site; to the adoption of new technologies to increase the performance of the building system in terms of environmental comfort. The best-known tools–LEED, BREEAM, DGNB, etc. [9] are used to classify the performance level of new constructions, and of the existing ones, when subjected to a restoration intervention. Despite not being compulsory, they have been used for large-scale designs and constructions, making energy saving the main evaluation object; this is related to the economic advantage produced by the significant reduction in energy consumption for high-performance buildings. None of the most popular protocols envisages a specific evaluation area for social sustainability or–at least–for the human factor [10], even though the latter is crucial for the attractiveness of real estates. Moreover, certifications do not consider the substantial differences–demographic, physiologic, socio-cultural, etc. among building users, as they adopt the needs and expectation of a standard average user [11].

This research is aimed to support the definition of IEQ and its evaluation methodologies, by examining the indicators used by the best-known protocols: indicators are intended as minimum requirements for the evaluation of users’ well-being in their living environments. For this purpose, the scope of the research is limited to in-use residential buildings. As premised, the literature review shows that the positive characteristics of a given location can turn into a disadvantage for another one and this leads to subjective results: then, an in-depth study in the present research is performed on the evaluation criteria based on soft data, that consider living spaces according to users’ perception. For this purpose, the well-known protocols BREEAM and LEED have been compared with the more recent WELL, an evaluation tool generated through an interdisciplinary collaboration between researchers in architecture and clinical medicine, aimed to the transform the built environment in the name of human health and psycho-physical well-being [12].

2. Methods

Nowadays, the use of building quality evaluation tools is a consolidated practice, which has led to the development of one or more protocols in several countries (45 around the world). In order to carry out specific research on social sustainability and indoor quality, the starting point has been the analysis of the certification protocol WELL, managed by the International WELL Building Institute (IWBI). This choice has been performed as this protocol is constituted by indicators related to social aspects by 97%: this rate is significantly higher than all other protocols, which consider these aspects by the 30% in average [13]. Even though this protocol provides a huge quantity of information referred to the social dimension of IEQ evaluation by itself, the literature review was extended to at least two more protocols for completeness. The other 44 protocols consider the social dimension almost with the same percentages; so, the selection was performed according to the “crosswalk” initiative [14], developed by IWBI together with some partners among the main founders of international evaluation systems. This initiative was highly praised in the real estate as it was aimed at the obtainment of a double certification through the alignment between the WELL systems and additional protocols, by setting equivalences between the criteria of each comparative system. The alignments have been processed by the IWBI together with the Building Research Establishment (BRE) Global Ltd. and the Green Building Council (GBC). Among the most recent certification protocols, we have chosen those with specific features for the evaluation of existing residential building, to circumscribe the study to living environments. Hence, the protocols analyzed and compared are the following:

- -

- WELL V2 pilot Q1: certification issued by GBC, managed by IWBI (USA), 2021, pilot project;

- -

- LEED v4.1 O + M Existing Buildings: certification issued and managed by USGBC (USA), 2019 [15];

- -

- BREEAM International In-Use v6: certification issued and managed by BRE (UK), 2020 [16].

WELL and LEED protocols have the same Certificate Authority, and their model structures have the same pre-requisites, credits, and scores. In the first phase of the research, the three protocols have been examined one by one to select evaluation indicators for social sustainability. These latter have been collected in summary tables, and classified by macro-category, purpose, evaluation criteria, credits, and weight on the whole evaluation process. Since the study focuses on user perception, it was checked whether the evaluation criterion of each indicator required quantitative information regarding Building Performance (BP), to be determined through observation, tool measurement, or qualitative information based on User Perception (UP): that is, hard data or soft data.

The second research phase focuses on research quality. The adherence between the protocols and the principles outlined in the last conference of the Architects’ Council of Europe (ACE)–and expressed in the Declaration of Innsbruck of the 4 May 2019 [17]–was verified. The purpose of the Declaration is to provide reflection on the concept of the quality of the built environment, shedding lights on the good practices for its evaluation, by premising that this topic does not allow absolute truths, as these evaluations depends on the context, and on individual users’ perception. The Document lists some essential characteristics (criteria) for places, which can serve as quality drivers, as they bring benefits to individuals and society.

The research verifies the correlation between such “essential characteristics” and the examined protocols. The realized summary table highlights the correspondence between the criteria listed in the Declaration and their presence in the evaluation process. If the outcome is positive, the indicators whose evaluation object matches the thematic area of the essential characteristic are specified.

3. Discussion

3.1. IEQ Evaluation According to Social Sustainability in WELL V2 Pilot Q1

WELL Building Standard is the first certification to measure and certify building characteristic according to their impact on human well-being, with a specific focus on the modalities of user comfort and health improvement. Based on the first, pioneering version of WELL v1, WELL v2 is the most tested and verified version of the WELL Building Standard as of today. The goal of this certification is users’ satisfaction, and it is achieved through both conventional IEQ parameters (heat, light, sound, and air quality) and complex physio-psychological dimension.

In order to harmonize WELL to the main bio-building standards, the International WELL Building Institute (IWBI) has developed “crosswalks” together with the BRE (BREEAM) and the US Green Building Council (LEED). These report the synergies between the various building standards, in order to simplify the double certification of designs through the recognition of equivalent and aligned requirements. Like LEED and BREEAM certifications, WELL is a global tool, diffused in more than 50 countries. However, unlike the others, the evaluation methodology of WELL does not depend on the design typology (existing building, new construction), nor on the in-use destination. This evaluation tool has a univocal procedure, with flexibility and adaptability to any construction, without a fixed scorecard: it uses a score system, with 110 points available in each project scorecard. There are a number “precondition parameters”, required to achieve the certification; the others are optimizations, chosen by the evaluator according to the building under certification. All optimizations are characterized by point values, which define the level of compliance of the building with a need, directly or indirectly related to the key needs of health and well-being. Projects that fulfill all preconditions and a given number of optimizations can achieve various certification levels: Silver (50 points), Gold (60 points), Platinum (80 points).

The goal of health and well-being, set by WELL for both resident and occasional users, is articulated into several items: Air, Water, Nourishment, Light, Movement, Thermal Comfort, Sound, Materials, Mind, and Community.

All the aspects show that the architectural quality of the house or workplace strongly affects life quality, with a deep influence on users’ physical and psychological health. The nature of the precondition parameters also shows, in WELL’s philosophy, a healthy building–both public and private–should guarantee all the quality levels indicated by the ASHRAE and UNI EN international standards. For example, the European standard EN16798 [2] defines minimum requirements for air quality and environmental parameters for thermal comfort, lighting, and acoustics. The WELL protocol establishes a no less than annual monitoring system for the evaluation of these parameters and refers to specific standards.

Thermal comfort is acceptable if the values correspond to those set by ASHRAE 55:2013 [18], ISO 7730:2005 [19] or EN 15251:2007 [20]. Concerning lighting, the following standards are considered: IES Lighting Handbook, EN 12464-1: 2011 [21], ISO 8995-1:2002 [22]. Air quality is verified if the building uses an effective mechanical or natural ventilation system, in compliance with the indications from the regulatory framework; it is evaluated through a constant monitoring of the values of particulate, organic and inorganic gases, radon. Air quality must be verified both at the operation stage and during maintenance activities: the maintenance plan must include the constant cleaning of filters, powder limitations, and the use of non-harmful materials and products (in particular, without asbestos, mercury, and lead).

Just like air, water is subjected to continuous performance tests as well, by monitoring the presence of contaminants. Times and modalities of control phases should be established in a specific management program, aimed at the prevention of risks related to the exposure to most common bacteria. WELL is the only certification to consider how an architectural project can influence a person’s nourishment, on the basis of the distance of the building from healthy products, and on its availability of spaces for the cultivation of biological crops.

This view is similar to Design Thinking: its human-centered methodology integrates design skills with social sciences, through an interdisciplinary collaboration based on an iterative process, to realize innovative, user-centered products and systems. Compared to common certification standards, which focus on environmental sustainability, WELL has a different perspective as it shifts the concern from technological performances to users and their needs. In addition to the Nourishment item, this is demonstrated by the presence of several themes linked to the physical and psychological sphere.

Concerning physical health, the certification can only be obtained if the examined project has spaces and facilities for physical activities, and if it improves general well-being through an ergonomic design, aimed at a better comfort in living environments, and at an increased safety in workplaces. An architectural project can contribute to mental health by integrating green spaces in the adjacent lot. Indeed, WELL implements well-known concepts from studies that have been carried out since the ’80s, concerning the effects induced by nature on mental and physical well-being. These findings lead to limit people’s exposure to hostile environmental conditions by reducing crowding feeling, acoustic and atmospheric pollution; moreover, to generate restorative effects through the view of landscapes that induce a relaxation state.

Stakeholders’ involvement during planning and operation phases is a precondition, aimed to encourage sociality. This must be demonstrated through a building management document that details the mission oriented to the consultation of the concerned parties: that is, it must outline occasions for the celebration of culture, art and/or the site itself, in one or more common spaces. Moreover, the management must include the diffusion of didactic material to inform users on the possible physical and psychological risks deriving from the use of the spaces; meetings with the users regarding their health and well-being must be organized several times a year, through surveys or focus groups. Surveys must assess the following items: indoor environmental quality of air, water, light, sound and thermal comfort (questions on thermal comfort must assess two yearly conditions, that is for the cooling and the heating season); ergonomics and esthetics, maintenance and cleaning, services (access to green areas and park areas, nutrition options), general building data, standard socio-demographic data and the time spent in the building.

The following summary table (Table 1) reports the precondition parameters for each issue, without an assigned score, together with the aims and the assessment criteria for each parameter.

Table 1.

Precondition parameters of WELL V2 pilot Q1.

Concerning optimization parameters, some are more related with housing units, while others are meant for other in-use destinations. Each parameter can be applied both to the built environment, and to the building design stage. In order to use the same term of comparison as with the other standards here analyzed, the evaluation has been performed on a living environment, in an existing residential building. Out of n. 84 optimization parameters in WELL, n. 25 are user-centered: their weight is associated a significant incidence (49 out of 110: around the 45%) and they provide several opportunities for the involvement of stakeholders. The parameters suggest several user-centered measures to designers or site managers: for example, the diffusion of a digital or physical library concerning the impacts of thermo-hygrometric conditions, indoor air quality and water quality on human health, in addition to real-time monitoring data; measures to favor proper nutrition, with zero-kilometer food consumption (planting supplies, watering system and gardening tools).

Technology control is one of the key actions for user well-being: this is an evaluation parameter as well and is related to thermal systems (with a focus on thermal zoning) and to shading and lighting systems, including illumination level, temperature, and color.

Some indicators, added in the most recent versions, derive from the new needs of protection from health risks, induced by the pandemic. The management of the building can have a deep influence on group immunity, through a strategic plan that defines places for tests and vaccines and establishes rules for the use and cleaning of the tools shared by all the residents, with diffuse signals and indications to regulate users’ behavior in common areas. Universal Design requirements are optimization parameters and have a scarce relevance (less than 3%) in the protocol, despite the high number of international regulations on some of its items, such as the elimination of architectural barriers.

WELL adopts one single item for the evaluation of: systems aimed at improving accessibility to all functions and areas, space flexibility, and usability; wayfinding strategies, which use color, consistency and other perceptible elements to support people with different cognitive skills; technologies to fulfill the needs of disabled people, at the free use of the residents. On the other hand, the need for spaces destined to physical activity and relax is strongly stressed: in addition to the abovementioned preconditions, several optimization parameters evaluate the presence of recreational spaces, setting a minimum of 7 m2 per regular occupant, and further areas for sports, recreational areas, green areas, indoor and outdoor design aimed at integrating nature with houses.

WELL is founded on users’ needs, and can verify if users are integrated and have an active role in the control of spaces. However, the collection of users perceptions, which occurs for almost all the abovementioned aspects, has a scarce incidence on the overall score of the evaluation, as its weight is around 10%. The following table (Table 2) reports the selection of the optimization indicators that can be used for the classification of the quality of a living environment, and for the evaluation of users’ involvement in the management of the living space.

Table 2.

Optimization parameters that imply an active users’ involvement in WELL V2 pilot Q1.

3.2. Social IEQ Evaluation in LEED v4.1 O + M

The USA-native LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) is the most used protocol in the world. The USGBC (US Green Building Council) has developed different versions according to the in-use destination of buildings; for each of them, the evaluation parameters are based on the American Technical Standard ASHRAE and on the European Standards EN and ISO. The certification considers the whole life cycle of the building and is aimed at guaranteeing the achievement of high performances in key areas of environmental and human sustainability (resource saving, site accessibility, energy efficiency, project innovation, material quality and IEQ). LEED has a credit-based rating system: some credits are compulsory (prerequisite), can be assigned for each category, and their sum determines the achievement of a certification level (certified 40–49, Silver 50–59, Gold 60–79, Platinum ≥ 80 points).

The protocol LEED v4.1 has a particular focus on IEQ, and several credits are related to accessibility, resource consumption (water, energy and materials), waste services, indoor air quality. The version LEED v4.1 O + M is specific for existing buildings in full operation and at least one-year occupancy. The document is divided into two sections: “Existing Building Scorecard” and “Interiors Scorecard”: the former performs a global evaluation of existing buildings, considering external areas as well; the latter is focused on the indoor environment. This research only considers the section on the indoor environment. IEQ evaluation is performed for most indicators, with a suggestion to the professional certifier to carry out an objective audit in order to verify the presence of measure for the improvement of indoor conditions. In some cases, these measures involve the performances of the building; in other case, they affect management policy.

Resource saving is a recurring theme for the evaluation, and the following items are estimated: water consumption (14%), energy consumption, annual gas emissions (33%), by also checking whether control and rationalization measure have been implemented for these resources. Moreover, the evaluation includes the outline of all annual purchases of consumption and construction material, in order to check whether they are recycled, rechargeable, biological, and if they have environmental product certifications (4%). The protocol also focuses on the management of services, such as waste disposal (8%) systems: in particular, verifications are related to the presence of specific storages for recyclable materials is recommended, and to the weight (in kg) of landfilled or incinerated materials, which must be under fixed thresholds. Other focused items include: the purchase of materials and products for building maintenance, which must be ecological and rationalized (prerequisite); the performance of maintenance and refurbishment actions according to a structured plan (prerequisite); the use of controlled procedures and non-hazardous products in ordinary cleaning, and the presence of a specific management plan for extraordinary cleaning (e.g., disinfestation of hazardous animal organisms) (prerequisite).

Air quality is the most relevant indicator in the whole evaluation procedure, and is analyzed according to several aspects: the calculation of the emissions from cooling systems, if present; the verification of the system of natural or mechanic ventilation; the measurement of VOCs, air inflows and outflows (prerequisite); the establishment of the smoking ban (prerequisite); the control on dangerous substances within the products for maintenance interventions, and within pesticides, when used (1%).

The philosophy at the foundation of the LEED certification is similar to WELL: the two standards are aligned in several aspects, and are designed to operate together, in a long collaboration aimed to orient the building environment toward a higher respect for human health and environment.

The minimum indoor air performances indicated in LEED perfectly match the requirement of proper ventilation, of implementation of filtering systems for polluting particles, and to the smoking ban in common areas indicated in the WELL certification.

Some credits were removed in version V4, compared to the version V2 of the LEED protocol, in order to simplify the certification procedure: this disadvantages LEED as compared to WELL in relation to thermal and visual comfort, for which WELL prescribes several in situ measurements (e.g., simulation of daylight improvement, occupants’ control of light levels in all spaces, control and monitoring of thermal parameters). Regarding some items, such as those related to ecological cleaning management, WELL demands specific requirements for the formulation of the program, for the cleaning protocol and for product storage; conversely, LEED accepts any work plan, as long as there is one.

Basically, WELL evaluates users’ opinions and includes their involvement in all parameters; in LEED, user surveys are carried out in a minor percentage, and have different typologies of question than WELL. In particular, in LEED v4.1 O + M user perception is collected through surveys only regarding waste production, accessibility of mobility services (14%), and indoor air quality (50% in combination with TVOC and CO2 measurement). The core of LEED is the measurement of the performances of technological systems (68%) and building management services (32%) through parameters that orient evaluations toward environmental sustainability, rather than social or economic sustainability. The following summary table (Table 3) reports the list of precondition and optimization parameters, along their weight on the overall evaluation, for the classification of the quality of living environments according to LEED v4.1 O + M.

Table 3.

Precondition and optimization parameters of LEED v4.1 O + M Interiors Scorecard.

3.3. Social IEQ Evaluation in BREEAM In-Use v6

The British certification BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method) has been the first system ever for the evaluation of the environmental and social impacts of buildings and has represented a model for the following certification systems. BREEAM In-Use International Residential outlines a performance standard, which allows evaluating existing residential buildings and living environments; the last published version is V6, and dates back to May 2020. BREEAM assigns reward scores through a rating system with 8 categories: health and well-being, energy, transports, water, resources, resilience, soil consumption and ecology, pollution. One or more credits are attributed for each good practice, according to the relevance of the category of the action, for the achievement of the building sustainability goal. Hence, requisites and categories have heterogeneous weights within the evaluation. The sum of the points in all categories represents the total score, which determines the final rating: Acceptable > 10%, Pass > 25%, Good > 40%, Very Good > 55%, Excellent > 70% or Outstanding > 85%; a building whose score is below 10% cannot be classified. The certification is divided into two parts: the first one, “Asset Performance”, analyzes the intrinsic performances of the buildings, while the second one, “Building Management”, examines the quality of building management and operation. As for the other evaluation systems described above, the scope of the analysis is here limited to the study of building performances.

The highest number of social aspects can be found in the category “Health and Well-being” (with a 17% incidence on the total evaluation). Visual comfort is evaluated by measuring glazed area (HEA 01), shading systems (HEA 02), indoor and outdoor lighting levels (HEA 03), artificial lighting quality (HEA 05), view out (HEA 06). With reference to thermal comfort, the presence of user control for temperature and humidity levels is verified (HEA 07). Air quality is verified: by checking whether in the house–or in the housing complex–there are sensors for CO and CO2 detection (HEA 09–10), whether the ventilation system, if present, is in compliance with USE and ANSI/ASHRAE standards (HEA 08); by performing the ISO 11,665 standard [25] test for the presence of radon (HEA 13); by checking for the storage of chemical substances, if present (POL 02), whether cooling and hearing systems are in compliance with the standards, concerning VOC emissions (POL 03), and whether there are systems for the detection of hazardous gases (POL 05). The first part of the document does not consider acoustic comfort, as it is evaluated within the building management. Concerning user’s health and comfort, other indicators evaluate the presence of recreational spaces (HEA 11) and presence of inclusive features (horizontal and vertical accessibility, assistive technologies and wayfinding, etc.) in living spaces (HEA 12). Sustainable mobility is considered too, as its advantages benefit both the environment and users: the presence of some features (proximity to public transport nodes, separate cycling and pedestrian routes, recharge stations for electric vehicles), can lead to an easy, healthy and safe use of public transport and personal electric vehicles (TRA 01–04). Economic sustainability, which has a significant impact on users’ psyche, is evaluated by verifying the presence of preventive actions for resource consumption, such as: planned maintenance (in order to avoid unexpected and costly interventions), waste recycle and reuse, building resources inventory (RSC 01–03). Moreover, a good number of indicators (14.5%) is related to users’ safety, through the evaluation of flood risk (RSL 01–02), risk by natural calamities (RSL 03), building durability and resilience (RSL 03), and by verifying the presence of an alarm system (RSL 05). The category “land use” includes the evaluation of the percentage of cultivated area: apparently, this is related to environmental sustainability, but actually it influences users’ well-being, as it affects several factors, such as air quality, shading, thermal comfort, psyche (LUE 01). Other indicators are related to environmental sustainability and have not been listed as the paper deals with social sustainability; likewise, a relevant part of the document deals is focused on the evaluation of building energy performances (ENE 28.5%) and on sustainable water use (WAT 9%) but this has not been examined in-depth.

Hence, the weights can be summarized as follows: a weight of 40% (ENE + WAT + POL02) is exclusively related to environmental sustainability; a weight of 32.5% is distributed among indicators focused on both environmental and social sustainability (HEA09-10 + HEA13 + TRA01 + LUE + POL01 + RSL01-03); finally, a weight of 27.5% is attributed solely to social sustainability. Users’ involvement is almost absent: the analysis of the evaluation method of each indicator shows that user perception is considered by less than 5%, within the evaluation process (see Table 4). The comparison between BREEAM and WELL highlights the lower focus to social sustainability in the British protocol. For several items, WELL requires the execution of on-site performance tests by third parties, in addition to instrumental measurements. WELL often refers to the man-nature couple, by suggesting the use of natural materials, patterns, forms, colors and sounds within housing units, and recalling the supportive role of nature toward indoor and outdoor, thermal and visual comfort. The control of parameters by users is a fundamental element in both protocols; moreover, WELL encourages “shared control” for multiple users. Among the activities carried out in proximity of living environments, WELL suggests additional services, such as common recreational spaces (common vegetable gardens and kitchens, green areas, and spaces for physical activities), and defines several specifications for services located in closer proximity (e.g., a minimum size for common areas, in relation with living space; a minimum number of stations for sustainable mobility, or a maximum distance for public transports). WELL also includes an annual resource inventory, aimed at quickly providing information for maintenance and emergencies, in addition to practical training and frequent communication between users and technical experts. The following summary table (Table 4) reports the selection of precondition and optimization parameters, together with their weight on the overall evaluation, used to classify the quality of living environments according to BREEAM In-Use.

Table 4.

Precondition and optimization parameters of BREEAM In-Use Asset Performance.

4. Baukultur Criteria in the Declaration of Innsbruck vs. Evaluation Methods

The culture of quality design for living environments contributes to the pursuit of the common good and is the main subject of the conjunct Declaration signed in Davos in 2018 [26], by the Ministers of the States that have joined the European Cultural Convention. The document highlights the need o introduce a high-quality Baukultur at a political and strategic stage. The term “Baukultur” includes every human activity that transforms the built environment, and influences design and construction quality and processes [27].

The Declaration of Davos states that a construction quality culture does not only fulfill functional, technical and economic needs, but also social and psychological needs, and that this should be included in regulatory frameworks. Construction quality has a fundamental impact on the people’s behavior and daily life: in fact, it strengthens the sense of belonging and allows users to identify with their living environment, improving integration and civic sense.

More recently, the Declaration of Innsbruck (May 2019) “How to Achieve Quality in the Built Environment: Quality assurance tools and systems”, presented at the Conference of the Architects’ Council of Europe (ACE), cites the previous Declaration, and marks a further fundamental step to clarify the good practices for the evaluation of quality in the built environment. The ACE Declaration highlights the complexity of this evaluation process with respect to specific factors, among which the context, which is always different: that is, advantageous characteristics in one location can represent disadvantages in a different one. Moreover, the quality of the built environment partly depends on one hand on the perception of the individuals who evaluate it; however, some essential characteristics are indeed inherently associated with attractiveness, with economic, social, environmental, and cultural benefits to individuals and society. The Declaration lists the following essential characteristics for the evaluation of the quality of a place: aesthetics, habitability, environment friendly, accessibility and mobility, inclusiveness, distinctiveness and sense of place, affordability, integration into the surrounding environment.

The ACE declaration also suggests the following principles for the evaluation process: quality must be determined through interdisciplinary discussions, with the involvement of political actors and citizens, through a place-based (taking into account the specificity and the history of a place), holistic (considering all the social, environmental, cultural, and economic impacts) and “live” (the reuse of the existing built environment must be promoted) approach, with more flexible regulatory frameworks.

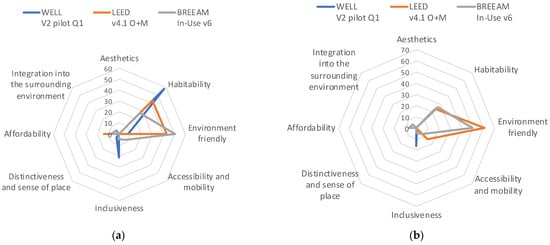

The evaluation indicators certification standards, analyzed in this paper, can be associated with almost all essential characteristics, yet with a heterogenous incidence (see Table 5, which reports the correspondences between indicators of each certification system, with essential characteristics). Hence, it seems that certification systems are aligned with the ACE criteria–aside from place aesthetics as in each certification system there is at least one indicator per criterion. However, the calculation of the weight distribution in the overall evaluations shows that most indicators evaluate Habitability (40% WELL; 33.5% LEED and 26.7% BREEAM) (see Figure 1a,b) and Environment Friendly (4% WELL; 52% LEED and 50.2% BREAAM). The correlation between indicators and items of the characteristics matches the propension of each certification toward a specific dimension of sustainability: the main goal of BREEAM and LEED is to assess the design of a building allows a high efficiency, a reduced quantity of polluting emissions, and high resistance to climate change during its whole life cycle; WELL attributes a higher weight to the technical characteristics of the building that provide safety, healthiness, and comfort. The analysis of the weight of the indicators shows inhomogeneity between certification systems with respect to Accessibility and mobility (0.5% WELL; 7% LEED and 7% BREEAM), Distinctiveness and sense of place (2% WELL; 0.5% LEED and 0% BREEAM), Affordability (1.5% WELL; 7% LEED and 6.8% BREEAM), and Integration into the surrounding environment (2.5% WELL; 0% LEED e 4.5% BREEAM).

Table 5.

Comparison between the essential quality characteristics from the Declaration of Innsbruck 2019 and the indicators in quality certifications WELL, LEED and BREEAM.

Figure 1.

Thematic areas of the certifications, compared to the criteria from the Declaration of Innsbruck 2019 (a) Comparison of precondition parameters. (b) Comparison of optimization parameters.

Inclusivity (18.5% WELL; 0% LEED and 4.8% BREEAM) is one of the main purposes of WELL for the achievement of the main goal of health and well-being; the focus on the Design for all, which is present in several criteria within the evaluation process, clearly shows that. The abovementioned percentages have been calculated according to the mean of the values of the precondition and optimization parameters. The value leads to acknowledge a gap between European theoretical systems, synthetized in the Declaration of Innsbruck, and the real evaluation tools in use. This shows the need for a harmonization, considering the vast use of certification systems and the economic interests associated with them within the real estate market.

5. Conclusions

The literature review has shown a wide agreement regarding the influence of living environments on people’s well-being; however, the evaluation and the realization of healthy and comfortable buildings can be a complex task for administrations and professionals. Building certification standards assist designers in taking into account aspects related to sustainability, and orient interventions toward technological solutions that increase living comfort. Moreover, certifications influence choices in the real estate sector, by guaranteeing valid design choices and a correct management; from the collectivity’s standpoint, they are a conventional declaration of building quality. High-quality built environments raise interest and attract investors; stakeholders’ appreciation toward certified buildings is reported in recent research. For example, the real estate value can increase by 7–11% as a function of the judgement of LEED evaluation; the certification does not affect only market value, but also the time-to-market [28].

The most diffuse building sustainability certification protocols, which have been examined in this paper, are WELL, LEED and BREEAM: their evaluation criteria consider design, construction and management from an environmental, economic and social standpoint, and in relation to well-being, yet in different ways and with different weights. Apart from the individual differences of the three examined standards, mostly related to the rating systems, all of them are based on hard data, and mainly evaluate building performances. The constant reference to international standards orients the evaluators toward the collection of measurable performance parameters, to be compared with those fixed by regulations. This is particularly related to environmental aspects (energy and resource consumption), and as a consequence a smaller focus is given to social sustainability, and even a smaller one to users’ survey.

A useful evaluation must effectively respond to stakeholders’ needs; however, the stakeholders are a multitude, with diverse interests, objectives, restrictions, and preferences, and they all require a specific, non-assimilable evaluation perspective [29]. Discussing and sharing design choices with users, through iterative and interdisciplinary processes, can lead to unstandardized, customized participative solutions, with a stronger grip on users’ interests.

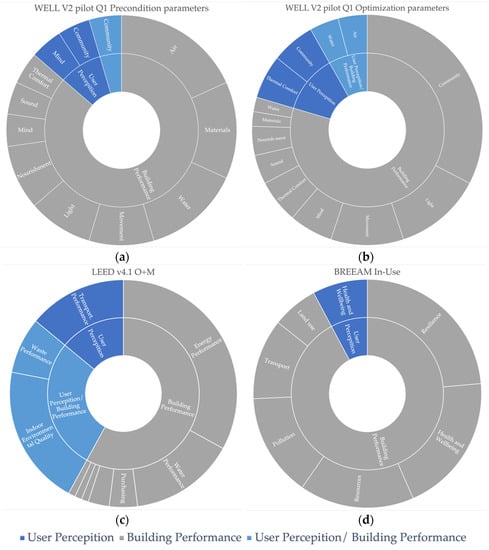

In such evaluation processes, users’ involvement can be defined as “passive”: that is, users are sensibilized, receive information on environmental parameters, and services that fulfill their daily needs. However, the collection of their opinion (user experience) is still a scarcely pursued path (in the examined standards, in the overall evaluation: 11% precondition parameters in WELL, 10% optimization parameters in WELL; 0% precondition parameters in LEED, 28% optimization parameters in LEED; 10% BREEAM) (see Figure 2a–d). For example, parameters regarding health rarely involve user perception, which could be helpful to avoid pathologies such as Sick Building Syndrome; instead, the highest weight is attributed to contaminant measurement, to the verification of ventilation technologies that determine indoor air quality and to the relationship with outdoor spaces.

Figure 2.

Weight of “user experience” in the examined standards, in the overall evaluation. (a) Comparison of WELL V2 pilot Q1 precondition parameters. (b) Comparison of WELL V2 pilot Q1 optimization parameters. (c) Comparison of LEED v4.1 O + M optimization parameters. (d) Comparison of BREEAM In-Use parameters.

Concerning “passive” involvement actions, WELL has the highest number of indicators, specifically aimed at users’ well-being and health: for this reason, it often integrates the other two certification systems through the so-called “crosswalk” plans to harmonize evaluations.

Furthermore, in none of the three certification protocols there is an interrelation between some of the analyzed factors: for example, the light which is linked to the external and internal shading and partly affects the temperature and humidity.

There are some cultures that use housing only for sleeping and some that live most of the year inside the buildings. This is another aspect that the protocols do not investigate, and which is closely related to the user. Moreover, depending on the “time of confinement “some aspects should have a greater weight than others.

Moreover, all three certification standards share a limited applicability on the most diffuse typology of built environment, that is modern buildings in reinforced concrete. These buildings are far from the concept of environmental sustainability, as they have null energy performances; lack economic sustainability since they require a continuous maintenance on materials; are often located in dense and overcrowded areas, and this has a strongly negative effect on social sustainability. Through aimed restoration interventions, these buildings could host high-quality spaces; however, the presence of excessively restrictive compulsory requirements–as shown by some of the criteria in the examined evaluation processes–excludes the possibility to valorize these buildings in the future. As an example, a residential building might hardly have a specific plan for legionella; in most cases, it is rare to find common areas for sport activities, for the in situ cultivation of biological products or for the local conversion of waste into resources. Presumably, the regeneration of this heritage could be effectively encouraged by adapting the base level of the certifications to the maximum potential of the existing building stock through customized solutions, more oriented toward final users’ needs, than to standardized parameters that involve complex technologies.

Funding

This research was funded by the Italian Ministry for the University (MIUR) with the project PON “Research and Innovation 2014–2020” Section 1 “Researchers Mobility” with D.D. 407 of 27/02/2018 co-financed by the European Social Fund–CUP B74I19000650001–id project AIM 1890405-3, area: “Technologies for the Environments of Life”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Dorizas, P.V.; De Groote, M.; Volt, J. The Inner Value of a Building—Linking Indoor Environmental Quality and Energy Performance in Building Regulation; Buildings Performance Institute Europe (BPIE): Bruxelles, Belgium, 2018; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- BS EN 16798-1:2019; Energy Performance of Buildings—Part 1: Indoor Environmental Input Parameters for Design and Assessment of Energy Performance of Buildings Addressing Indoor Air Quality, Thermal Environment, Lighting and Acoustics; BSI: London, UK, 2019.

- De Giuli, V.; Da Pos, O.; De Carli, M. Indoor Environmental Quality and pupil perception in Italian primary schools. Build. Environ. 2012, 34, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dear, R.J.; Brager, G.S. Developing an adaptive model of thermal comfort and preference. ASHRAE Trans. 1998, 104, 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Frontczak, M.; Wargocki, P. Literature survey on how different factors influence human comfort in indoor environments. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 922–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanger, P.O. What is IAQ? Indoor Air 2006, 16, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, D. The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Acampa, G. Linee guida delle politiche europee: Requisiti qualitativi e criteri di valutazione dell’architettura. SIEV Valori Valutazioni 2019, 23, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, R.; Wilkinson, S.; Bilos, A.; Schulte. A comparison of international sustainable building tools. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual Pacific Rim Real Estate Conference, Gold Coast, Australia, 16–19 January 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Attaianese, E.; Acierno, A. La progettazione ambientale per l’inclusione sociale: Il ruolo dei protocolli di certificazione ambientale. TECHNE J. Technol. Archit. Environ. 2017, 14, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- International WELL Building Institute. WELL Building Standard: WELL Certification v2™ Pilot. 2020. Available online: https://v2.wellcertified.com/v/en/overview (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Altomonte, S.; Schiavon, S.; Kent, M.G.; Brager, G. Indoor environmental quality and occupant satisfaction in green-certified buildings. Build. Res. Inf. 2017, 47, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guldager Jensen, K.; Birgisdottir, H. (Eds.) Guide to Sustainable Building Certifications; Statens Byggeforskningsinstitut, SBi: Aalborg, Denmark, 2018; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- International WELL Building Institute. People + Planet Applying LEED and The WELL Building Standard. Strategies for Interiors, New Buildings and Existing Buildings Seeking Dual Certification. LEED Crosswalk. 2020. Available online: https://a.storyblok.com/f/52232/x/202a35bb61/leed-crosswalk-with-q4-2020-addenda.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- U.S. Green Building Council. LEED v4.1 Operations and Maintenance. 2019. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/resources/leed-v41-om-beta-guide (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Building Research Establishment. BREEAM In-Use International Technical Manual: Residential V6.0. 2020. Available online: https://byggalliansen.no/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/SD243_BREEAM-In-Use-International_Residential-Technical-Manual-V6.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Architect’s Council of Europe (ACE). Statement Presented on 4 May 2019 in Innsbruck (Austria) on the Occasion of the ACE Conference “How to Achieve Quality in the Built Environment: Quality Assurance Tools and Systems”. 2019. Available online: https://www.ace-cae.eu/fileadmin/New_Upload/_15_EU_Project/Creative_Europe/Conference_Quality_2019/Inn_Stat_EN_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- ASHRAE/ANSI Standard 55-2013; Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013.

- BS EN ISO 7730:2005; Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment–Analytical Determination and Interpretation of Thermal Comfort Using Calculation of the PMV and PPD Indices and Local Thermal Comfort Criteria; BSI: London, UK, 2005.

- BS EN 15251:2007; Indoor Environmental Parameters for Design and Assessment of Energy Performance of Buildings, Addressing Indoor Air Quality, Thermal Environment, Lighting and Acoustics; BSI: London, UK, 2007.

- BS EN 12464-1:2011; Light and Lighting; Lighting of Work Places—Indoor Work Places; BSI: London, UK, 2011.

- 8995-1:2002 (CIE S 008/E: 2001); Lighting of Work Places—Part 1: Indoor; International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 62.2-2016; Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality in Residential Buildings; American National Standards Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2016.

- BS EN 16247-2:2014; Energy Audits—Part 2: Buildings; BSI: London, UK, 2014.

- ISO 11665-4:2012; Measurement of Radioactivity in the Environment—Air: Radon-222—Part 4: Integrated Measurement Methods for Determining Average Activity Concentration Using Passive Sampling and Delayed Analysis; International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- European Ministers of Culture. Davos Declaration Towards a High-Quality Baukultur for Europe, Office Fédéral de la Culture Section Patrimoine Culturel et Monuments Historiques. 2018. Available online: https://davosdeclaration2018.ch/media/Brochure_Declaration-de-Davos-2018_WEB_2.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Niglio, O. Baukultur e la Dichiarazione di Davos 2018. Per un Dialogo tra Culture. EDA, Esempi di Architettura. 2018. Available online: http://www.esempidiarchitettura.it/sito/journal_pdf/PDF%202018/55.%20Niglio_Baukultur_EdA_2018_2.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Rebuild Italia. Green Building: Valori e Tendenze. Ricerca Promossa da Rebuild Italia e Condotta in Collaborazione con CBRE ITALIA e GBCI EUROPE. 2018. Available online: https://www.rebuilditalia.it/it/MS/green-building-valori-e-tendenze/ (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Bentivegna, V. Gli aspetti relazionali della qualità dell’opera di architettura. SIEV Valori Valutazioni 2019, 23, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).