Abstract

There has been growing interest in the ways that individuals connected with nature during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly when they were alone in solitude. This study explored key themes describing individuals’ relationships with nature during this period and, more specifically, when individuals were relating to nature during time spent alone. Sixty participants (aged 19–80 years) discussed solitude during in-depth interviews. Participants were from different backgrounds and 20 different countries of origin. Thematic analysis was conducted by two architects (who may have been sensitive to the functional interaction of spaces in connecting people and nature) and identified descriptions of nature from broader narratives of solitude and time spent alone. Extracts from interview transcripts were coded using hierarchical thematic analysis and a pragmatist approach. The results showed that natural spaces were integral to experiencing positive solitude and increased the chance that solitude time could be used for rest, rejuvenation, stress relief, and reflective thought. Being in their local natural spaces also allowed participants to more spontaneously shift from solitude to social connection, supporting a sense of balance between these two states of being. Finally, solitude in nature, in part because of attention to shifting weather, gave a new perspective. As a result, participants reported increased species solidarity—the awareness that humans are part of an ecosystem shared with other species. We interpret the results in terms of the implications for built environments and the importance of accessing nature for well-being.

1. Introduction—Access to Nature Fosters Well-Being in Solitude

Humans have a deep connection with nature, which is expressed through their behaviour across a large number of domains, including through paintings, horticulture, architecture, poetry, and preferences for leisure time. Psychologists have understood this cognitive and emotional connection to be an important part of the human experience [1,2]. Nature connection positively affects psychological [3,4,5] and physical [6,7,8] well-being and mitigates psychological costs of stress [9]. Studies have shown that physically connecting with nature can foster this emotional connection to nature, improve hedonic and eudaimonic aspects [10] of well-being, and alleviate food insecurity through emotional connection to edible nature [11]. These benefits have policy implications [12]. For example, access to nature in cities can improve well-being through providing better air quality [13], and accessible nature connects communities [14].

The COVID-19 lockdowns disrupted everyday lifestyle and recreational choices and exposed many worldwide to largely unfamiliar stressors, uncertainties, and social isolation [15,16]. One disruption came in the form of the lockdowns imposed internationally, which extended the time spent in solitude for many [17]. Solitude—defined as the state of being alone and not physically with another [18]—can be understood to be a challenging (i.e., undermining well-being) or beneficial (i.e., increasing well-being) experience as a function of the circumstances in which it takes place [19]. During national lockdowns and periods of quarantine, solitude took the form of self-isolation, giving rise to the view that it reflected a pandemic of loneliness [20,21,22]. Findings have also suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic heightened the risk of loneliness for groups who were already at risk of feeling lonely (low-income households, 18–30 year olds, single-person households, and people over 65) before the pandemic [21,22], findings that were identified in a number of different countries [23].

Despite costs, an intriguing outcome of lockdowns has been increased appreciation of natural spaces, which has been reflected in descriptive findings that the majority of people spent more time in nature and had the intention to continue doing so [24,25]. Complementing this, some evidence has suggested that nature and nature connection played important roles in individuals’ recreation during the COVID-19 pandemic, with 89% of adults agreeing or strongly agreeing that green and natural spaces were important to their mental health [26]. Similarly, Forest Research found that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a sense of appreciation—a feeling of connection and access to nature, trees, and woods—helped people maintain or improve their well-being, as well as promoting a general valuing of natural spaces [27]. Additional work has found that people across the UK felt increased connection to nature after the first lockdown as compared to previous years [28]. Empirical studies have also indicated that nature connection fostered well-being during lockdowns [29,30]. It may be that accessing nature became a newly formed habit for some or that people felt a greater desire to be in nature. Recognizing the potential benefits of this connection, public health experts have seen connection to nature as a grounding for ecotherapy practices and have found that it can help people recover from the negative psychological effects caused by the COVID-19 pandemic [31].

As such, nature may have played an important role in encouraging a positive sense of well-being during lockdowns. Intriguingly, it may have mitigated the “pandemic of loneliness” to some extent by making solitude time more positive and rewarding for many. Though there is little research on the role of nature during solitude per se, one foundational paper has shown that, when spending time alone in solitude, connection to nature can create a sense of positive solitude [32]. The authors found that time in remote nature (wilderness) resulted in a greater focus on the environment and self/introspection, as well as greater care for the wilderness [32].

Much is known about the well-being outcomes of everyday nature connection but little about how nature connection manifests when it is employed as a psychological resource during periods of stress or adjustment, particularly when individuals connect to nature as they spend time in solitude on their own. The current project aimed to close this gap and extend our understanding of the impact of access to natural spaces by exploring its role as a resource to improve time spent alone in solitude in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Current Research

To date, there has been little research on the specific beneficial ways that individuals connected with nature during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly when they were alone and in solitude. This study therefore explored connection to nature in order to understand key themes that describe the meaning of nature connection during periods of solitude. The definition of nature varies across research studies [33], but in this study, we decided to use the term “nature” to refer to every physical element, living or static, that has not been made directly by humans. Therefore, “connection to nature”, in this study, refers to a positive sense of connection to the physical elements from nature and/or an appreciation of these elements.

To explore the role of nature as a potential resource in solitude during pandemic lockdowns, the current data collection and analysis investigated this topic from the ground up, extracting various experiences of—and relationships with—nature from broader narratives of solitude.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

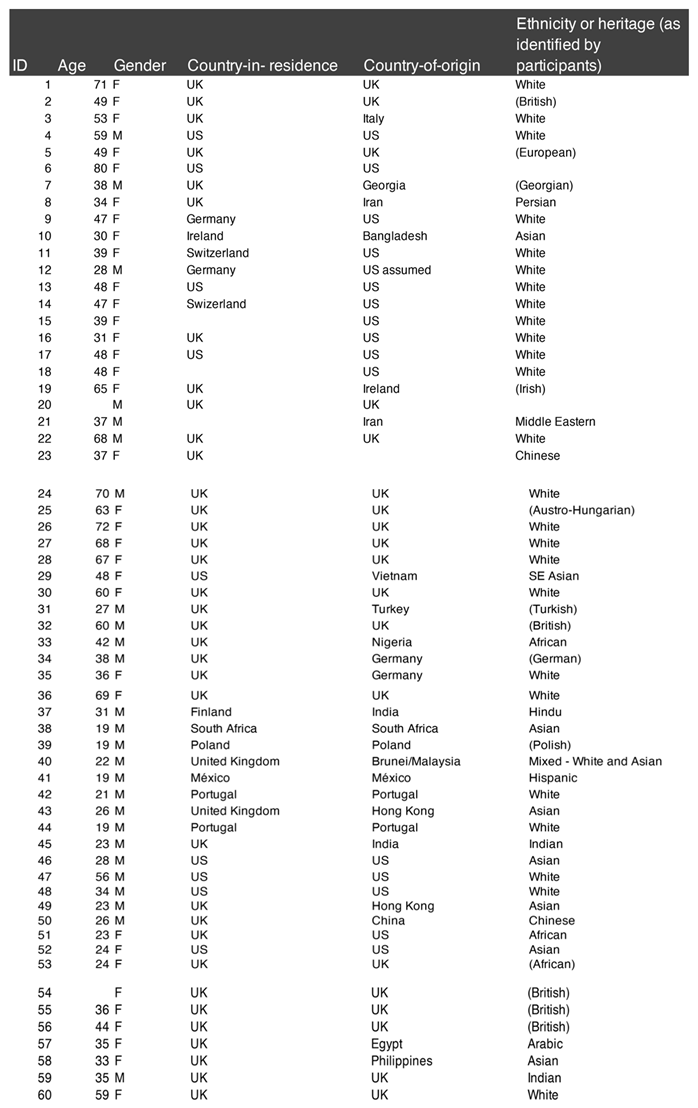

Sixty in-depth interviews (Appendix A) were conducted with adults aged 19–80 years. Participants were recruited through advertisements within the community, including by writing mailing lists in local communities and using university mailing networks; by inviting public (but anonymized) figures who had discussed their solitude to take part; and through Prolific.co, an online platform connecting participants and researchers. The goal was to recruit participants from different cultures and geographic locations, with different educational and socioeconomic levels, and of different, genders and adult ages. The final sample included individuals from 20 countries of origin, including Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Georgia, India, Iran, Italy, Nigeria, Mexico, the Philippines, Portugal, and Vietnam, and represented individuals of various ethnicities (e.g., in broad categories, 36 identified as White, 12 identified as East Asian, 6 identified as Middle Eastern or Persian, and 4 identified as Black or Hispanic). In total, the majority (37) were residents of the UK; 9 were residents of the US, and 11 resided in other countries (Appendix B). Participants who self-identified as fluent in English were recruited and all interviews were conducted in English. The sample also included students, unemployed individuals, and full-time workers and retirees, as well as healthy individuals and others living with long-term illnesses. We purposely sampled from these populations to capture distinctive life experiences, challenges, and perspectives (see more about the approach to sampling in [19], which focuses on resilience predictors of solitude outside the context of natural spaces). Participant characteristics are presented on the project OSF page.

3.2. Procedure

The study procedures were conducted for approximately one year starting in May 2020. The study followed APA and BPS ethical guidance and received approval from the School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences at the University of Reading #2020-034-KM. Interviews then took place online through Zoom or Teams or by phone and lasted approximately 45–60 min. Interviews were semi-structured, and the interviewer followed a predetermined set of questions. The research team conducted the interviews directly. Interviews involved questions that addressed: (1) the role of solitude in participants’ lives, (2) what participants’ time alone looked like on a daily basis, (3) participants’ positive and negative experiences in solitude, (4) participants’ thoughts on what made solitude good for them and, (5) participants’ thoughts on if and why they were resilient in solitude. The interview schedule is presented on the project’s OSF page, and it did not include questions about nature or natural spaces. However, during the initial analysis of the data, we noted strong themes having to do with the natural world when participants discussed their positive solitude.

We identified patterns in the data using thematic analysis [34,35]. After the data had been collected, we refined themes through multiple rounds of revisions aimed at achieving conceptual clarity and extracting meaning and placed them into hierarchical categories, with particular sensitivity to internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity [34,36].

Additional steps were taken to ensure data analysis was rigorous. One consideration was reflexivity; that is, how the perspectives and backgrounds of the lead interviewer and analyst would bias or colour how the data were interpreted (Schoenberg et al., 2011). The lead analyst kept a diary of codes and his assumptions and reactions in line with best practices [37]. Both lead researchers (RS and MS) are British chartered architects and approached the data with an interest in connection to nature and design of the built environment. However, analysis was kept open to all themes that emerged, whether relevant to built environments or disparate from them. With reference to the definition of nature stated in the introduction of this paper, during the coding, nature was coded as anything that was not made directly by humans, regardless of its context; for example, within the context of an urban street, seeing the sky and pigeons and breathing fresh air would be coded if spoken about.

4. Results

Participant interview content was initially coded under 23 headings. Each heading described a specific type of interaction with—or view of—nature. The nodes were then grouped into five themes (being in nature enriches solitude, community and socialising in nature, thinking of and thinking in nature, species solidarity, and elements and forces in nature) that are discussed within the main areas below. These overarching headings each described a way that nature changed the relationship with solitude and affected a sense of well-being.

4.1. Being in Nature Enriches Solitude

Solitude was deeply intertwined with nature, and nature was a positive element of wellness in solitude. This became apparent when interview participants were asked “what are the things that first occur to you when you hear the word solitude, and what does that mean to you personally?”. Natural settings were described frequently both in terms of past experience and as places conjured by the imagination.

“… the woods and the mountains especially, just kind of like really empty nature-scapes where the only sounds are like nature sounds and there’s just nobody around. It’s kind of unspoiled”Ppt 11 Ref [3]

Nature was also a way of coping with unwanted moments of solitude (i.e., isolation) or, conversely, using solitude to cope with life stress. When reflecting generally on experiences of solitude, many participants recounted instances of being in nature and described a general feeling of calm and comfort from observing nature at the macro scale. The physical scale of natural environments (i.e., increasing in size and quality) gave them a chance to reflect and take perspective on life experiences. Whereas, for some, nature helped to compensate for the lack of human connection when alone, other participants talked about actively seeking solitude in large, open natural spaces to cope with life stresses.

“Yes, it almost feels like being alone on the moon or something sometimes, you know. And it’s so, it’s so comforting because everything is so big and it’s been around for so long, and it’s just so massive it makes you and all your problems and your whole life seem so insignificant. And that’s a sort of great feeling, I think. It’s just so reassuring.”Ppt 11

“There’s only you and the sea and the cliffs and the grass, but it’s not a bad thing. Solitude is more positive than being lonely. It’s a different thing altogether.”Ppt 1

Walking (including walking the dog) was one of the most commonly discussed means of coping in isolation, invariably linking discussion to the natural surroundings. The participant below helpfully triangulated the link between activity, solitude, and being in nature. Though less succinctly, many others also described the mutually beneficial relationship of these three conditions.

“And so I mean it’s true that the activity helps but it’s also … it’s kind of a combination of the two or, rather, the three; getting out in nature, being, you know, in solitude, and also doing some activity.”Ppt 11

For some, specific elements of nature played an important role in appreciating and benefiting from natural surroundings. Participants talked about the pleasure of witnessing the growth of plants and the activities of animals and insects. In paying such close attention to their surroundings, many reflected on how being in nature stimulated different senses.

“I’m aware of the smells and the sounds and the air on my skin. And one thing I’ve actually enjoyed about the lock in is, “Why don’t you have a walk?” Because, you know, just going for a walk. Just taking a walk for no reason has never been part of what I do but it has been since then and really I’ve become so aware of the sounds of nature and the colours—so more than before. And that’s been one of the good things.”Ppt 25

Stepping down a scale to consider the domestic setting (home environment), we observed frequent references to the satisfaction and benefits of tending to and being in smaller natural spaces, such as private gardens. Participants spoke of the benefit of routine and habit when using garden spaces—as well as simply “pottering around” and spending time in a relaxed and unstructured way—and the well-being attained from just completing ad hoc and non-essential tasks. Gardens also offered an opportunity for growing food. A number of participants who described spending time in their gardens felt that having the garden was a privilege. Participants who were unable to be in nature expressed frustration.

“So, it’s quite nice just to sort of think that you can just sort of lose yourself in the greenhouse for an hour or two and get a little bit of work done. But often it’s just sort of thinking time and me time, to use a phrase that I don’t like, but it is me time, I suppose.”Ppt 32

“(I had) cabin fever, it was awful. I was yearning for the sea air, the coast, anything.”Ppt 28

“That I’m eating healthy, it’s something I’ve planted myself. It’s organic. Although you can go to the store and buy it, it’s not the same as growing your own vegetables.”Ppt 29

“I used to go to a gym and a sauna and swim three times a week near the monastery, and so that was my physical—main physical thing. Whereas if you’re working out in nature, gardening, it’s such an extremely pleasant environment. It’s just a very physical thing to do.”Ppt 19

Other forms of exercise and leisure activities were also commonly cited as reasons to be out in nature and often led to reflection about the social benefits of exercising outdoors, which is reported on separately under the next heading.

4.2. Community and Socialising in Nature

Although many participants used nature as an opportunity to have quality alone time, others enjoyed breaking solitude by seeking others out for brief interactions in natural environments. For example, many participants discussed exercising outdoors, and several felt that exercising in nature led to opportunities for socialising. From walking the dog to open water swimming, several people described enjoying the random encounters with others when outdoors. Participants also described how socializing changes when in nature, such as the facilitation of positive non-verbal direct communication with others. In addition to being a mutually convenient place to meet others for exercise, being outdoors has benefits for well-being.

“I feel I’m much more positive when I go outside to communicate with nature. It’s kind of part of my socialising as well… say hello to the joggers”Ppt7

“But most of the time if I’m not hiking I want to share it with my kid because we get along, we as a unit get along better in nature than we do anywhere else and I recognise that fact. We have these amazing discussions.”Ppt 18

“…you just feel, you don’t need to talk there, you just become part of the nature. And then you”

Although most discussion around social contact in nature centred on direct contact and communication with others, there were a number of participants who described acts of “people watching”, where being in nature where they could watch people enhanced their time alone.

“Sometimes, it’s nice just to sit, like, if you’re on holiday, just to sit and watch the world go by, that’s solitude, as well, because you’re just sitting there, maybe on the seafront or something, and you people watch, but you’re actually sitting there quite quiet and relaxed.”Ppt 36

4.3. Thinking of and Thinking in Nature

Participants expressed that thinking about nature and being in nature helped relax their minds when in solitude. Themes of mindfulness, therapy, and spirituality were commonly referenced. Some reflected on how recent experiences of isolation had led to new practices in mindfulness. Other participants talked about mindfulness practice more as a routine behaviour, such as taking part in yoga, meditation, or a daily walk. Some participants talked about mindfulness without necessarily describing it in these terms, speaking more generally about clearing their thoughts and mind.

“I’m just like, I need a break, and my idea of a break is just retreating into that space, and then just taking a walk, kind of like being on my own and just looking at nature, kind of doing mindfulness as we speak.”Ppt 10

“So, I think I almost have little rituals where I do certain things which then get me into a state of calm or solitude, or I might go for a walk, and in which case, I’m somebody who notices thing when they walk, so flowers and birds and blossom, and I actively note it. So, I think I do do particular things to let me feel solitude.”Ppt 2

“It’s calming actually, because your mind is pretty empty. My mind is pretty empty.”Ppt 1

Others explained that being in nature actually increased their focus or ability to rationalise their thoughts, including positive reflections about the past. The reflective environment of the interview led many to recall childhood experiences of being in nature, drawing comparisons between their living environment now and a time that was often more “free” and connected to nature.

“I’m watching the grass, the bugs, the birds. So I may go in with a noisy mind, typically I come out with a clearer mind unless of course I’m really fixated on something. But then I’ll also—sometimes it helps me start thinking.”Ppt 13

“I mean it was so different when I was a kid anyway, I mean when we were children there were hardly any cars on the road. There was freedom.”Ppt 28

4.4. Species Solidarity

There were many instances where participants described behaviours or beliefs that alluded to “species solidarity” [38]. Species solidarity concerns being cognisant of how (our) human lives are entwined with the living beings that form our global ecosystem. Experiencing nature during time alone enhances species solidarity, which in turn leads to reflection on human impact on other species and the environment. In the quote below, the participant encapsulates the issue of being disconnected from nature through the pressures of work and domestic routine and then being jolted to engage in the outdoors by the rather more primal needs of the family dog or by being close to house plants.

“… the dog starts barking because she hasn’t been out for a walk, and that reminds me to close off the day and see who wants to come for a walk.”Ppt 5

“I think—I hate to say it, but it’s kind of like talking to your plants. So, to me, it’s living. To me, it’s personification, it’s something alive to me. That’s my companion, I guess you can say.”Ppt 29

Several participants spoke of the consequences of mankind’s negative impact on the planet, generally expressing sadness. One participant shared their personal aspiration to make positive changes and help the environment, and several other people inferred this through the discussion around growing their own food (linking with “being in nature enriches solitude”).

“I love it. I love it. It’s fantastic. You can use it to heal a great deal. It’s something that should grow and be on itself, and be balanced if you like. Unfortunately mankind has gone and screwed that so royally I’m not so sure the earth can survive. And in fact I’ve got a great deal of sympathy for the extinction rebellion.”Ppt 22

“I like the environment, so I’d like to see myself do something good for the environment in the future, as a long term purpose, such as, in the future, I want—I thought to my—sometimes walking in the park on my own helps me to envision, envision myself planting a new tree a week in the future, so that kind of links. And being on myself, being on my own, sometimes, helps me just to imagine and to envision the future that I want to manifest.”Ppt 39

4.5. Elements and Forces of Nature

Participants found that experiencing elements and forces of nature, such as the seasons and weather, contributed to positive solitude by encouraging reflection and helping them gain perspective, resulting in improved well-being. Discussion about seasons and weather evolved naturally around descriptions of natural settings. From a practical standpoint, many participants simply stated the limitations of certain weather conditions and seasons. However, in some cases, this led to reflections about imposed changes on the pace of life and synchronisation with natural rhythms. Seasonal changes are known to have a bearing on mood and wellbeing and one participant highlighted this as being even more acute in a rural setting. There were also frequent references to elements in nature, with descriptions of water and wind leading to much reflection about the stimulation of different senses.

“The weather controls pretty much everything, so as well as controlling it, I can go somewhere, or if it’s going to be comfortable outside; it controls pretty much everything I do and a part of my mental state is definitely depending upon the weather.”Ppt 4

“…I would say like the rhythm, like that’s what I really noticed, like if you’re in the mountains by yourself like there’s a rhythm of your own that takes over,”Ppt 11

“Where in winter if I’m in a storm and the storm ends and the sun comes out and it’s a nice mild day, that’s a real positive sort of thing. The environment a lot here can affect my mental state as well, because the environment is so overwhelming, it’s so dominating.”Ppt 4

“I was enjoying being rained upon, and humming to myself actually, as I walked by one pond to reach another, then I went – yes, and I was just paying attention to the sensations of the rain, the sensations, the lovely sound of silence that there was.”Ppt 19

5. Discussion

Periods of solitude—time spent alone—can feel unwanted and lonely, while in other contexts, solitude is felt to be a beneficial state for reflection and re-energization [19,39]. The current findings explored the role that nature played in creating positive solitude throughout the COVID-19 pandemic period to date and suggested that access to nature was an important, if not critical, part of positive versus lonely solitude.

We identified a theme that we termed “being in nature enriches solitude”. This theme reflected the sentiment that positive solitude was closely intertwined with natural spaces and that nature gave comfort and calm during moments of solitude. Natural spaces, especially those that were expansive and high quality, were seen as especially valuable when experiencing forced solitude during a global pandemic, in large part because they helped to regulate stress and rejuvenate. These findings—that natural spaces played a role in enhancing solitude’s ability to regulate stress—underlined the importance of easy access to nature and natural spaces during pandemic lockdowns [26]. Previous research has identified that nature-related pro-environmental behaviour elicits positive feelings towards nature that reduce loneliness more broadly, supporting the conclusions drawn in this study [40]. Closely related, the theme “thinking of and thinking in nature” represented statements that natural spaces make solitude a more productive time to help clear one’s thoughts, speaking to the mental benefits of being alone in social environments. These results conceptually replicate previous studies that suggest natural spaces provide a time for reflection [41] and creativity [42], as well as more proximal research showing that, when safety is held constant, experiencing natural environments in solitude can be used for rejuvenation [39]. Here, we found that nature may be especially important for these benefits from solitude and that, in part, these benefits provide a stress-regulating function. Broadly, we saw participants’ responses highlighting once again the importance of nature for mental health [3,4,5].

Our findings also suggested that, although solitude in nature was beneficial, some people appreciated an opportunity to break solitude by seeking out social interactions. Nature was described as helpful for spontaneous opportunities to connect with others, allowing people to enter in and out of solitude in a flexible way. We see these results as supporting the theory that people need a balance between social and solitary periods [43] and that natural spaces can help achieve this balance. The “community and socialising in nature” theme also highlighted increased social engagement when exercising outdoors, a finding that echoed previous research [44], where the outdoor space for exercising was conceived as somewhere where others can also pass through, highlighting the importance of scale and access. With or without exercise, connection to nature seemed to enhance people’s social interactions, potentially increasing community cohesion and the sense of belonging in a community [14,45].

Thoughts from participants referred to being in nature as actual green spaces rather than a replication of natural spaces, highlighting that we need access to natural spaces as well as benefiting from replicating nature in and around our homes as per biophilic design guidance; i.e., the chances for positive solitude in biophilic designed internal spaces may be lower than those for time spent in nature in green spaces. Considering these results from the perspective of architecture, built environment professionals are increasingly understanding the need to design spaces that give us contact with nature and a feeling of being in nature, and principles such as biophilic design principles [46,47] and biophilic urban planning [48] are being used as tools to design such spaces. Bridging these areas of urban planning with psychology can provide guidance for these designs. For example, the results of the current study suggested that natural spaces might be designed in urban spaces to support both social time (for example, in schools) and quiet solitude time; for example, in the form of gardens. Future work can explore these and other avenues to practically applying these results.

Along with exploring the role that nature plays in shaping well-being during moments of solitude, we also found that connection to nature in solitude reminded some of a sense of “multispecies solidarity” [38]—an understanding that humans are part of nature, interlinked with other living things and dependent on the survival of other living things. Our results showed that connecting with nature during time alone enhanced species solidarity by leading participants to think about our impact on other living things, which underpins the thinking that connection to nature raises awareness of environmental issues [49]. Psychologists have found evidence of an association between multispecies solidarity and pro-environmental behaviour and between nature connection and pro-environmental behaviour [49]. In the context of the climate and ecological emergency, this is an important finding. It suggests that, if we find ways to connect people with nature, we could increase their willingness to engage in pro-environmental behaviour, which, in turn, could help address the climate and ecological emergency. Importantly, the theme “species solidarity” highlighted the importance of natural spaces rich in biodiversity for connection to other species, with the quality of biodiversity interventions being key [50,51]. Both nature connection and, in a separate theme, awareness of shifting weather patterns and the influence that they had on our participants’ solitude moments put things in perspective for participants, helping them to think about themselves in relation to the natural world in a new and connected light.

6. Implications for Development

The findings presented in this paper suggest that the present lack of nature integration in more urban, deprived areas is a significant issue that needs to be addressed [52,53] in order to maximize solitude well-being and minimize loneliness during time alone. It has been found that designing spaces in healthcare settings that connect people with nature is therapeutic, helping to reduce pain and stress and improve emotional wellbeing, thus helping patients recover from physical and mental health problems [8,54]. Recently, research has shown that urban nature provides resilience for retaining well-being and enables social distancing during pandemics, particularly in dense urban areas [55].

This study especially highlighted the importance of how we design nature integration within places where people live and work. Maintaining and increasing access to nature in urban settings is a key part of sustainable cities, helping to achieve UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and SDG11 (Sustainable and Resilient Communities) [55,56]. In addition, urban nature can address SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) by helping improve the energy efficiency of buildings [57]; SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) by integrating edible nature and food production in urban areas and on buildings [58]; SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) [59]; SDG 13 (Climate Action) by enhancing resilience to climate change [60]; SDG 14 (Life Below Water), where blue infrastructure provides ecosystems for a variety of species [61]; and SDG 15 (Life on Land) [62]. Built environment professionals analysed people’s experience of their apartments during the COVID-19 restrictions and found that apartment design should create opportunities for connection to nature through the use of balconies due to the importance of contact with nature [48]. There are scales of influence that need to be considered, from the room where a person is sitting and the rest of their home layout to the outdoor space around their home, their street design, the neighbourhood design, and their wider city.

7. Limitations and Future Research

As this study was undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic, the findings regarding the relationships that people had with solitude and the role of natural spaces in those relationships may not extend to everyday solitude beyond crisis periods such as that experienced during the data collection period. Despite this concern, much of the research studying the importance of access to natural spaces took place before the pandemic and speaks to the lasting importance of nature for well-being. Similarly, solitude can be a lonely or restive space in everyday life [19], and we have little reason to doubt that the apparently important role that nature plays in this time will shift in years to come. Understanding this is an assumption, future research should be conducted to examine these themes qualitative or quantitatively.

Additionally, although we spoke with individuals from different backgrounds and cultures, we did not identify whether experiences with nature in solitude would be different for those who come from different cultures, such as collectivist versus individualist ones [63], where solitude, in general, may not play an important role and natural spaces can be more specifically designed to promote interpersonal interactions with community members and close social networks. We also suggest future research should explore these issues with individuals from more and less population-dense environments to examine whether natural spaces are indeed a missing resource for positive solitude time in urban environments. It may be that those living in rural spaces find positive alone time in natural spaces easier and more accessible and that benefits can be achieved by increasing access in cities specifically.

Indeed, we did not directly discuss with participants whether they connect to nature in urban or rural environments and how. This was undertaken intentionally to keep the discussion open in terms of different ways of accessing and relating to nature, but we likely missed important insights about differences in nature connection within each of these distinct environments.

In addition, although nature was prominent in discussions about solitude among participants, it would have been useful to explicitly ask participants to discuss their thoughts about the role that nature plays for them when experiencing solitude. This would open further opportunities for analysing the nature–solitude link and give further insight into the types of nature spaces that may be important for positive solitude experiences.

Further research on the design of nature integration to achieve these qualities would be beneficial and help increase the chances of positive solitude. This may be especially important for increasing the quality of life of those who experience choiceless solitude. For example, nature has been shown to help the recovery of medical patients [8,54] and may be especially important to incorporate for those who are in long-term treatment with intermittent human contact. Individuals may also be required to stay home alone because of physical restrictions [64], and incorporating natural environments into their home environment may help increase well-being for these outpatient populations. Considering there is an aging population [65], addressing these issues is increasingly important.

8. Conclusions

The results of this study highlighted the importance of experiencing nature for mental well-being during periods of solitude. We found that natural spaces were critical—sometimes even definitional—for positive solitude and enriched alone time. Solitude in nature offered the chance for rejuvenation, reflection, and stress relief. Natural spaces also meant that solitude time offered a new perspective and promoted species solidarity. The results highlighted the importance of nature integration at varying scales in urban environments. Nature can and should be incorporated into urban spaces to create thoughtful and quiet spaces for reflection and regulation. This can be undertaken at different scales, from spaces inside buildings, around buildings, and in streets to larger green spaces. The quality of the biodiversity within these spaces, and the scale and access rights of these spaces, can be developed to facilitate alone and social time.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, M.S., R.S. and N.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Research Council (ERC) grant number SOAR-859810.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and received approval from the School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences at the University of Reading #2020-034-KM.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study can be found at 10.17605/OSF.IO/XPJ37.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Solitude Interview Questions

- Goals:

- (1)

- Allowing for nuance / complexity (looking for meaningful solitude, what does that look like and how does one achieve it)

- (2)

- Move away from too concrete, although some is good, into more speculation and internal focus

- (3)

- To understand both solitude itself (what makes it good/bad), and understand resilience within it (who are the kinds of people who say, ‘I miss being alone’?)

- Introduction

- Recognition that life has changed a lot in the past month, and that solitude may mean something different at the moment.

- Curious about how experiences reflect what solitude was like before vs. now.

- Recognition that solitude may have been challenging or had rewards, or both. Interested in that range of experiences.

- Questions

- (1)

- What comes to mind when you hear the word “solitude?” What does solitude mean to you, personally?

- (2)

- On an average day, how much time do you spend alone?

- (3)

- What does being alone look like for you? Can you tell me about it?

- a.

- The events/circumstances (morning walk, commute, crossword puzzle, etc.)/why are you alone?

- b.

- Can you elaborate... specifically about something that takes a chunk of time (not a few minutes here or there)?

- c.

- Could you also think about an extended period, and how those are different?

- (4)

- Generally, how do you feel when you’re alone?

- a.

- Do you anticipate it (in a good/bad way), and it is as good/bad as you imagined?

- b.

- What do you do to reduce negative or enhance positive feelings?

- (5)

- Do you ever choose to be on your own?

- (6)

- Describe your most recent negative solo time—what were you doing, where were you, and what made it tough?

- a.

- Had anything happened in your life to make alone time harder?

- b.

- How did you feel then? How do you feel during moments such as these?

- c.

- What did you think then? What kinds of thoughts do you have in moments such as these?

- d.

- Do you think there’s anything internal that contributes to those times being difficult?

- (7)

- Describe your most recent positive solo time—what were you doing, where were you, and what made it rewarding? (If only outdoors, is there anything indoors that applies as recent/meaningful?)

- a.

- Had anything happened in your life to make alone time rewarding?

- b.

- How did you feel then? How do you feel during moments such as these?

- c.

- What did you think then? What kinds of thoughts do you have in moments such as these?

- (8)

- Why do you think, for you, solitude is sometimes negative and at other times positive? OR mostly/always negative, OR mostly/always positive?

- a.

- Do you think there’s anything about you, in particular, your personality or outlook, that makes these instances of solitude either positive or negative?

- (9)

- [If not always negative] What are the benefits of solitude for you (creativity, grounding, etc.)? What’s exceptional or meaningful about being alone?

- (10)

- In talking about these experiences, do you think any differently about solitude and what it means to you?

Appendix B

References

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, J.L.; Benassi, V.A. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of emotional connection to nature? J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennigan, K. Therapeutic potential of time in nature: Implications for body image in women. Ecopsychology 2010, 2, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamitsis, I.; Francis, A.J. Spirituality mediates the relationship between engagement with nature and psychological wellbeing. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M.; Bruehlman-Senecal, E.; Dolliver, K. Why is nature beneficial? The role of connectedness to nature. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 607–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, M.v.d.; Bird, W. Oxford Textbook of Nature and Public Health: The Role of Nature in Improving the Health of a Population; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Twohig-Bennett, C.; Jones, A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.; Torquati, J.C. Examining connection to nature and mindfulness at promoting psychological well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 66, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsko, C.; Lindberg, K. Experiencing connection with nature: The matrix of psychological well-being, mindfulness, and outdoor recreation. Ecopsychology 2013, 5, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlmann, K.; Lin, B.B.; Ross, H. Who cares? The importance of emotional connections with nature to ensure food security and wellbeing in cities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, R.; Depledge, M.; Maxwell, S. Health and the Natural Environment: A Review of Evidence, Policy, Practice and Opportunities for the Future; Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2018.

- Abhijith, K.; Kumar, P.; Gallagher, J.; McNabola, A.; Baldauf, R.; Pilla, F.; Broderick, B.; Di Sabatino, S.; Pulvirenti, B. Air pollution abatement performances of green infrastructure in open road and built-up street canyon environments–A review. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 162, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.; Balmford, A.; DeHaan, C.R.; Gladwell, V.; Bradbury, R.B.; Amano, T. Seeing community for the trees: The links among contact with natural environments, community cohesion, and crime. BioScience 2015, 65, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgland, V.M.; Moeck, E.K.; Green, D.M.; Swain, T.L.; Nayda, D.M.; Matson, L.A.; Hutchison, N.P.; Takarangi, M.K.T. Why the COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic stressor. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0240146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, B.R. COVID-19 as a stressor: Pandemic expectations, perceived stress, and negative affect in older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, e59–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usher, K.; Bhullar, N.; Jackson, D. Life in the pandemic: Social isolation and mental health. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2756–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.V.T.; Weinstein, N.; Ryan, R.M. The possibilities of aloneness and solitude: Developing an understanding framed through the lens of human motivation and needs. In The Handbook of Solitude: Psychological Perspectives on Social Isolation, Social Withdrawal, and Being Alone; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 224–239. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, N.; Nguyen, T.-V.; Hansen, H. What time alone offers: Narratives of solitude from adolescence to older adulthood. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 714518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palgi, Y.; Shrira, A.; Ring, L.; Bodner, E.; Avidor, S.; Bergman, Y.; Cohen-Fridel, S.; Keisari, S.; Hoffman, Y. The loneliness pandemic: Loneliness and other concomitants of depression, anxiety and their comorbidity during the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 275, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, F.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Who is lonely in lockdown? Cross-cohort analyses of predictors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health 2020, 186, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Tilburg, T.G.; Steinmetz, S.; Stolte, E.; Van der Roest, H.; de Vries, D.H. Loneliness and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A study among Dutch older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, e249–e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, J.C.; Clark, A.E.; d’Ambrosio, C.; Vögele, C. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown stringency on loneliness in five European countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 314, 115492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J. COVID-19 Strengthens Our Connection with Nature. 2020. Available online: https://www.discoverwildlife.com/news/covid-19-strengthens-our-connection-with-nature/ (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Lemmey, T. Connection with Nature in the UK during the COVID-19 Lockdown; University of Cumbria: Carlisle, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- England, N. People and Nature Survey: How Are We Connecting with Nature during the Coronavirus Pandemic? 2020. Available online: https://naturalengland.blog.gov.uk/2020/06/12/people-and-nature-survey-how-are-we-connecting-with-nature-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic/ (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- O’Brien, L.; Forster, J. Engagement with nature and Covid-19 restrictions. In Quantitative Analysis; Forest Research: Gwynedd, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ONS. How Has Lockdown Changed Our Relationship with Nature? 2021. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/environmentalaccounts/articles/howhaslockdownchangedourrelationshipwithnature/2021-04-26 (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Jenkins, M.; Houge Mackenzie, S.; Hodge, K.; Hargreaves, E.A.; Calverley, J.R.; Lee, C. Physical activity and psychological well-being during the COVID-19 lockdown: Relationships with motivational quality and nature contexts. Front. Sport. Act. Living 2021, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Evans, M.J.; Tsuchiya, K.; Fukano, Y. A room with a green view: The importance of nearby nature for mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ecol. Appl. 2021, 31, e2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, P.; Banerjee, D. “Recovering with nature”: A review of ecotherapy and implications for the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 604440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrie, W.T.; Roggenbuck, J.W. The dynamic, emergent, and multi-phasic nature of on-site wilderness experiences. J. Leis. Res. 2001, 33, 202–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couvet, D.; Ducarme, F. What Does ‘Nature’ Mean. In Palgrave Communications; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 6, p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Sauzendeoaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzy, D. Qualitative Analysis; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nijhuis, M. Species Solidarity: Rediscovering Our Connection to the Web of Life. 2021. Available online: https://e360.yale.edu/features/species-solidarity-rediscovering-our-connection-to-the-web-of-life (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Staats, H.; Hartig, T. Alone or with a friend: A social context for psychological restoration and environmental preferences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Soucie, K.; Matsuba, K.; Pratt, M.W. Meaning in life mediates the association between environmental engagement and loneliness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, S.; Lima, M.; Silva, K. Nature can get it out of your mind: The rumination reducing effects of contact with nature and the mediating role of awe and mood. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 71, 101489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.J.; Lee, K.E.; Hartig, T.; Sargent, L.D.; Williams, N.S.; Johnson, K.A. Conceptualising creativity benefits of nature experience: Attention restoration and mind wandering as complementary processes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 59, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littman-Ovadia, H. Doing–being and relationship–solitude: A proposed model for a balanced life. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 1953–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, M.; Gladwell, V.F.; Gallagher, D.J.; Barton, J.L. Influences of green outdoors versus indoors environmental settings on psychological and social outcomes of controlled exercise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Lu, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Cao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y. Natural outdoor environment, neighbourhood social cohesion and mental health: Using multilevel structural equation modelling, streetscape and remote-sensing metrics. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 48, 126576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, W.; Ryan, C.; Clancy, J. Patterns of Biophilic Design [14 Patrones de diseño biofílico](Liana PenabadCamacho, trad.); Terrapin Bright Green, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Downton, P.; Jones, D.; Zeunert, J.; Roös, P. Biophilic design applications: Putting theory and patterns into built environment practice. In KnE Engineering; Knowledge E: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2017; pp. 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, T.; Halleran, A. How our homes impact our health: Using a COVID-19 informed approach to examine urban apartment housing. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2021, 15, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, C.M.; Schmitt, M.T. Do people who feel connected to nature do more to protect it? A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Baró, F. Greening the City: Thriving for Biodiversity and Sustainability; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; p. 153032. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Zhu, Q.C.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Chen, X.Y. Biodiversity at disequilibrium: Updating conservation strategies in cities. In Trends in Ecology & Evolution; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nadkarni, N.M.; Hasbach, P.H.; Thys, T.; Crockett, E.G.; Schnacker, L. Impacts of nature imagery on people in severely nature-deprived environments. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 15, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J.J.; Thompson, C.W.; Aspinall, P.A.; Brewer, M.J.; Duff, E.I.; Miller, D.; Mitchell, R.; Clow, A. Green space and stress: Evidence from cortisol measures in deprived urban communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 4086–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totaforti, S. Applying the benefits of biophilic theory to hospital design. City Territ. Archit. 2018, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, K.; Barthel, S.; Colding, J.; Macassa, G.; Giusti, M. Urban Nature as a Source of Resilience during Social Distancing Amidst the Coronavirus Pandemic. 2020. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:1501270 (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- UN. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, P. The effectiveness of green roofs in reducing building energy consumptions across different climates. A summary of literature results. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 151, 111523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samangooei, M. Individuals Cultivating Edible Plants on Buildings in England; Oxford Brookes University: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Voordt, T.V.d.; Jensen, P.A. The impact of healthy workplaces on employee satisfaction, productivity and costs. J. Corp. Real Estate 2021, 25, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamukcu-Albers, P.; Ugolini, F.; La Rosa, D.; Grădinaru, S.R.; Azevedo, J.C.; Wu, J. Building green infrastructure to enhance urban resilience to climate change and pandemics. Landsc. Ecol. 2021, 36, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negret, H.R.; Negret, R.; Montes-Londoño, I. Residential garden design for urban biodiversity conservation: Experience from Panama. In Biodiversity Islands: Strategies for Conservation in Human—Dominated Environments; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 387–417. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Bilan, S. Green infrastructure: Systematic literature review. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 35, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Individualism and Collectivism; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, N.J. Timely insights into the treatment of social disconnection in lonely, homebound older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 709–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN. World Population Ageing 2019 Highlights; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).