Abstract

Preparing preservice teachers for professional engagement is important for teacher education and has received much attention over the past decades. Therefore, finding effective training and coaching to improve the professional skills of preservice teachers (PSTs) is of great importance. This study developed a proactive online training program (POTP) based on a model of work-integrated learning (WIL) activities and teacher education. The objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of the POTP in improving PSTs’ professional skills. The participants consisted of 83 PSTs in an education program from two universities in Thailand. This study comprises three phases: phase I, the development of the POTP; phase II, a quasi-experimental study with a pretest-posttest design; and phase III, a focus group discussion. The findings demonstrated that PSTs in the group in which the POTP was implemented exhibited increased professional skill development compared to the PSTs in the control group, i.e., without the POTP. Analysis from the focus group confirmed that participants gained knowledge and satisfying online tools, and they were found to have better skills. They also revealed that the POTP not only improved professional skills but also enhanced the inspiration and confidence of the PSTs and supported their life and career goals and preparation. Therefore, educators, practitioners, and policymakers involved in pedagogical content knowledge development in teacher education programs can apply the POTP and assessment models proposed in this work to develop essential soft skills for PSTs and to better prepare them for their careers as teachers in the 21st-century digital era.

1. Introduction

Improving teacher training systems and teacher professional skills is a challenge in almost every country [1]. Recent research suggests that, in online and blended learning environments, especially in the post-COVID-19 pandemic era, PST programs and teacher professional development (TPD) programs should focus on building the skills and competencies of educators in the following dimensions: using education technology tools to improve teaching and learning [2,3], learning management systems, using data analytics as part of effective teaching, analyzing patterns and trends in student behavior and learning progress, developing effective teaching techniques and methods [4,5], preparing several types of work-ready students by applying work-integrated learning (WIL) processes [4], and designing mechanisms for assessments of learning that are more efficient and timely [6].

The disruptions of technology and the COVID-19 pandemic have challenged the education system and TPD programs, causing both students and teachers to dramatically adapt to new learning environments and to develop a deeper understanding of what constitutes effective teaching [7]. These affect the active use of distance and online technology in many areas [8] to enhance teaching–learning and management processes [9,10]. Thus, information communication technology (ICT), digital technology, social media, and social networking currently play important roles in establishing the effective coexistence of distance and education management [11,12]. In addition, these online technologies are applied to the processes of teacher production [13,14,15].

Presently, however, the continual improvement of the professional competency of PSTs through online training and the mentoring system is minimal [16], although the implementation of online mentoring through professional learning is effective in improving TPD [17]. According to several researchers, instructional multimedia promotes better learning motivation and performance than does the traditional approach [18,19,20]. In a similar vein, the study of Carrillo and Flores [21] highlighted that the COVID-19 pandemic impacted pedagogy’s need to integrate digital technology to support teaching and learning.

The readiness for and engagement in online teaching, learning, and training programs for PSTs became essential concerns during the pandemic [22]. Therefore, adequate support and development of technology-related professional pedagogical content knowledge and motivation for PSTs in education programs are needed [23,24]. However, research has demonstrated that adopting technology for teaching and learning and providing authentic training experiences in educational systems for PSTs are rare [16], even though information technology and online teaching–learning are necessary to enhance their teaching abilities and professional skills [9,25,26]. Adequate access to teaching resources, problems with implementing new teaching strategies, issues regarding technology use, and large classroom size management are challenges currently confronting PST programs in many countries, including Thailand [27]. In addition to the above concerns, teacher education programs must be revised to improve teacher skills, advance teacher visions, and promote teacher actions that meet societies’ demands for excellent, professional teachers. With that said, little is known about the benefits of training and coaching PSTs across the various dimensions or the degree to which such training and coaching contributes to creating professional teachers who are prepared to enter the teaching workforce [28,29,30]. This is especially true regarding a PST’s ability to incorporate online tools. Therefore, this research developed the Proactive Online Training Program (POTP), which is designed to provide PSTs with an opportunity to enhance their essential professional skills. Whereas regular training programs utilize competency-based and content-based approaches, and focus only on self-learning and on the development of the ability to integrate learning theories and real practices, e.g., professional knowledge and experiences, performance, and personal conduct, the POTP prepares work-ready teachers (PSTs) by applying work-integrated learning (WIL) and assessment models, which include, in addition to the development of essential soft skills, such as modern education and digital technology tools (online and blended learning environments), professional inspiration, management systems, creative problem solving, and communications and relationships with co-workers in the workplace, which are important in the digital and post-COVID-19 pandemic era.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of the POTP intervention in PST education programs to improve the professional skills of PSTs by examining the following research questions: (1) Does participation in the POTP positively impact the professional skills of PSTs, compared to PSTs who do not participate in the POTP? (2) How satisfied were the participants in the POTP with the formatting and organization of the online training program during the pandemic? (3) How effective and appropriate did the PSTs find the POTP?

The following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

PSTs participating in the POTP interventions enhance their professional skills.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

PSTs participating in the POTP intervention express satisfaction with the online training program.

In addition, to determine the interest level of the PSTs and their perceptions of the appropriateness of the POTP, a focus group discussion approach is applied. The POTP and assessment models applied in this work are expected to help educators, practitioners, and policymakers involved in pedagogical content knowledge development in teacher education programs to develop essential soft skills for PSTs and to better prepare them for their careers as teachers in the 21st-century digital era.

1.1. Teachers’ Production in Thailand

Teacher quality in Thailand has been commonly criticized, which has led to teacher education reform in the nation. Therefore, Thailand has many projects and programs designed to improve the education system with a focus on training student teachers as well as certified teachers. These programs focus on the development of effective, professional skills and abilities, including meeting the challenges of global changes and mastering the use of technology [31,32]. Realizing the importance of improving education in the country, the Ministry of Education (MOE) of Thailand announced in 2019 a teacher improvement plan to enhance the standards of teaching programs to include the integration of educational technologies and a competency-based approach [33]. According to the MOE announcement, the effective enhancement of current teacher production competency is essential, as the skills and competencies of teachers in Thailand should consist of personal attributes that are relevant to maturity and a strong sense of professionalism [34]; a combined form of relevant suites that address attitude, knowledge, ability, and skills to create a distinct teaching ability for enhancing and empowering learners [35,36]; keeping up with the modern digital world [37,38]; and the use of English in their professional work [39,40]. Accordingly, the teacher training programs in Thailand must be founded on a competency-based rather than a content-based approach by focusing on self-learning and on the development of the ability to integrate learning theories and real practices through the implementation and embracement of the PST program, which is a form of the WIL approach to teacher training [33,41].

The PST program in Thailand is operated according to the established professional standards for teachers, namely, (a) professional knowledge and experiences, (b) performance, and (c) personal conduct [41,42], and is intended to promote the appropriate concepts and to develop worldviews regarding inclusive education. It is argued that doing so can lead to successful sustainable education and education for all [43], which is the key means to fulfilling teachers’ professional standards, competencies, spirit, and ideology [33,41,44]. Thus, for the continuous development and transformation of novice PSTs to become more advanced and competent PSTs, it is imperative to include the following in PSTs programs: conferences, research, and coaching to enhance new skills; training in the use of technology; and courses to advance content knowledge [44]. However, due to the lockdown of the university during the pandemic, the preparation of PSTs had to shift from face-to-face to virtual learning environments, where it has been especially challenging to meet the standards of the curricula [45].

1.2. Work-Integrated Learning (WIL)

WIL is a pedagogical approach whereby students learn from the integration of experiential learning in educational and real workplace settings [46,47]. Students who participate in WIL systematically develop skills and knowledge in the before-, during-, and after-placement phases [48]. Currently, the WIL approach in the higher education curricula of Thailand and other countries does not focus just on student placement [4] but also on a variety of experiences in workplace environments, such as developing professional skills to increase job opportunities, learning and understanding work culture, and developing self-management skills. Connecting learners with businesses and communities provides a work-ready learning experience [46,48]. Thus, the WIL approach is an essential part of preparing workers to embrace their careers with the competence and confidence necessary in their profession [49,50,51]. However, again, the COVID-19 pandemic has created a critical and immediate impetus for rapid change in WIL practices and the adoption of online training guidelines [52].

The MOE of Thailand has been promoting the application of the WIL approach as a crucial path for supplementing teacher competency in PST programs [33,41]. WIL is an effective method that allows PSTs to transform their academic knowledge into real experiences by granting them work in many areas, such as community service programs, teacher and researcher assistantships, school work–study programs, and work exchanges, as they earn their degrees and prepare themselves for their professions [53]. Accordingly, implementing the WIL approach is believed to be an effective strategy for helping PSTs meet the requirements of their profession and should be a critical part of their professional preparation in the PST program [41,54].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

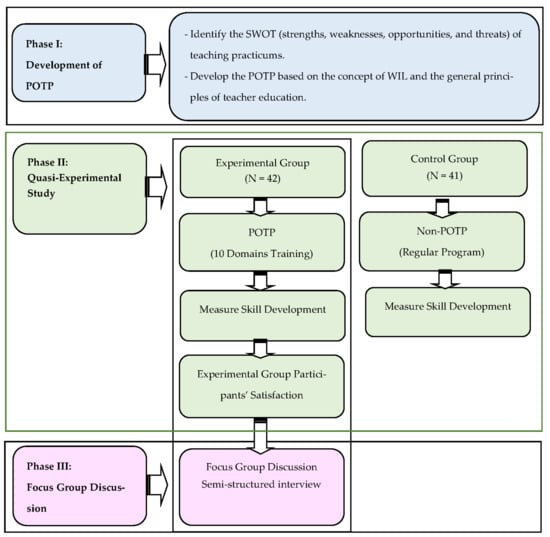

To understand the effectiveness of the online program and the context of training that was developed for the PST education program of two universities in Thailand, this study comprises three phases. Phase I includes the development of the POTP based on the literature review, and content validation is conducted. A pilot study is then carried out, and revisions of the questions are made based on the findings of that study. Phase II, a quasi-experimental study, is performed to assess the effectiveness of the POTP, and phase III consists of a focus group discussion.

2.1.1. Phase I: Development of POTP

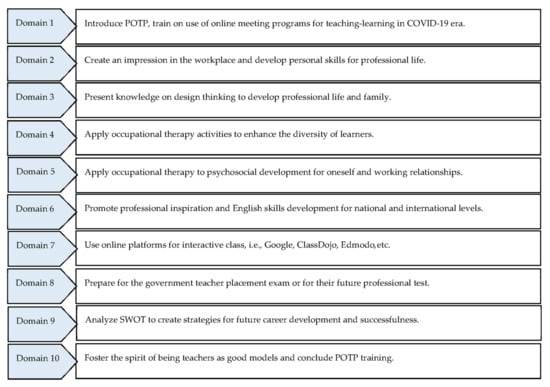

The first phase was to identify the SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) of teaching practicums according to student teachers’ perceptions as the road map for designing training programs and for developing the POTP for PSTs. The guides for developing the POTP were based on the concept of WIL and on the general principles of teacher education with a strong focus on pedagogical content knowledge. The POTP content was validated by five educational experts and five representative PSTs. The POTP was a pilot online program that consisted of ten essential domains, as presented in Figure 1, in which domains 6, 7, 8 and 10 are parts of the regular program. This domain online course was designed to increase essential professional skills during the PSTs’ learning process.

Figure 1.

Domains of 10 essential domains of POTP.

2.1.2. Phase II: Quasi-Experimental Study and Timeframe

A quasi-experimental research approach using a before–after nonequivalent group design was used in Phase II. This type of design consists of two groups: the experimental group and the control group. Both groups were given a pretest and posttest using a repeated measures design. To evaluate the effects of the POTP for PSTs on improving important professional skills, a before and after intervention comparison was conducted. The experimental group was treated with the ten domains of the POTP (1.50 h/time) from January to April 2021 and October to December 2021 during the PSTs’ internship program in the second semester of the 2020/2021 academic year. The last post-treatment measurement took place on April and December 2021, and then each of the experimental group participants received an online survey to assess their level of satisfaction with the POTP and intervention.

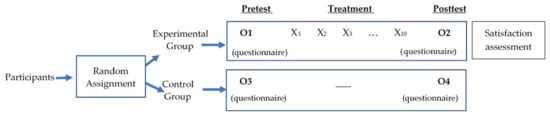

The participants were recruited into the study and were randomized into either the experimental or the control group using the quota selection method. The experimental group participants were treated with the ten domains of the POTP and were granted access to and guidance through the ZOOM program. The control group received a regular course as a non-POTP. Upon completion of each domain, both groups were provided information and resources for their own professional development as well as access to counseling services, if desired. The quasi-experimental research design is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Quasi-experimental research design of the study. Description: O1 = Premeasurement for experimental group, O2 = Postmeasurement for experimental group, O3 = Premeasurement for control group, O4 = Postmeasurement for control group, X = Each treatment for experimental group.

2.1.3. Phase III: Focus Group Discussion

After completing the POTP, eight PSTs from the experimental group were invited to join a focus group discussion. The focus group began with the moderator welcoming the attendees and introducing herself and the aim of the focus group discussion. Each participant was invited to introduce themselves to establish familiarity. The session was approximately 45 min in length.

The steps of the research process are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The steps in the research process.

2.2. Participants

The research population comprised fifth-year PSTs in the education programs at two universities in Thailand. All 83 participants were volunteer PSTs (100%) with a bachelor’s degree. The participants were randomly selected for the experimental or the control group. There were 42 volunteers in the experimental group (13 males, 29 females), in which the POTP was implemented. A total of 41 volunteers were placed in the control group (5 males, 36 females). In addition, 8 volunteers from the experimental group were selected to participate in the focus group discussion (4 males, 4 females). The inclusion criterion of the participants was that they must be fifth-year undergraduate students in an education program. The exclusion criterion was that the students did not have the time to participate in online training.

2.3. Instruments

Data were collected using two questionnaires and semi-structured interviews.

2.3.1. Questionnaires

(1) Skill assessment scale for PSTs (SASPST): The SASPST is a self-assessment tool consisting of 20 aspects graded on a five-point Likert scale (from 1 being completely unable to 5 being completely able). The SASPST consists of two subscales: general information (5 aspects) and competency level (15 aspects). A higher score means a higher level of competence. The SASPST is based on the concepts of professional standards for teachers, career preparation for 21st-century skills and for the COVID-19 pandemic era, classroom interaction, and the POTP domains. This scale was validated by six experts in the field and was used to assess competencies before and after the POTP program. The SASPST exhibited strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.879 for the experimental group and 0.760 for the control group.

(2) PSTs’ satisfaction with the training (PST-SAT): The PST-SAT assesses training satisfaction of the experimental group after the intervention. The questionnaire consists of ten items on a five-point Likert scale (from 1 being very dissatisfied to 5 being very satisfied). The scale exhibited strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.924.

Both questionnaires were developed by the researchers by applying and adapting previous questionnaires used to assess satisfaction with training programs [51,55]. They were evaluated for content validity by five experts, and the quality of each item was initially assessed using the index of item–objective congruence (IOC), with scores ranging between 0.80 and 1.00 for each aspect/item, thus indicating that the instruments exhibit reliability and are appropriate for implementation. The mean score of the five rating scales and their interpretation are as follows: 1.00 to 1.79 = poor, 1.80 to 2.59 = fairly poor, 2.60 to 3.39 = fair, 3.40 to 4.19 = fairly high, and 4.20 to 5.00 = high [56,57,58].

It should be noted that participants’ satisfaction with the regular program (for the control group) was not assessed, because we would only like to assess their perception on their skill development before and after participating in the regular program and not their satisfaction with the regular program itself.

2.3.2. Semi-Structured Interview

The semi-structured interview method was applied in the focus group discussion, which included eight volunteers. The aim of the discussion was to obtain information regarding the program after completing the POTP. The interview consisted of five guide questions: (a) How effective or beneficial is the POTP content for developing skills? (b) Does the POTP inspire you to pursue your career? (c) How suitable are the POTP formats, such as the use of the ZOOM program for training, the training duration, and the preparation for participation? (d) How appropriate is the POTP for developing PST programs for universities? and (e) How possible is it to implement the POTP concepts into authentic program practice?

2.4. Data Collection

Pretest and posttest data collection techniques were used in the experiment stage. Both the experimental and control groups received before and after program questionnaires to measure and compare the effectiveness of the training program and measure the degree of change in skill development. Before and after measurements were based on self-assessments using Google Forms as an online survey platform. The initial pre-survey was administered at the beginning of the semester, and the final post-survey was administered at the end of the semester.

A semi-structured interview format for the focus group discussion with PSTs provided an opportunity to delve deeper into the volunteers’ responses and to ask/discuss follow-up questions that led to richer and more compelling data [59]. The volunteers responded to open-ended questions for one hour regarding their perspectives on the effectiveness and possibility of the POTP in the future.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Suranaree University of Technology under Application No. EC-63-90. All participants gave their informed consent to participate in the study. Before the study began, the researchers notified the PSTs of the study’s aims and their right to withdraw from the study at any time. Furthermore, to reduce the pressure of participating in the focus group discussion and provide more truthful and open answers, course teachers did not lead the focus groups.

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Quantitative

A quantitative data analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows version 18.00. Descriptive statistics were used to record the demographic information, analyze the data of all variables, and measure the degree of satisfaction with the POTP.

To determine the effectiveness of the training between the POTP group and the non-POTP group, a before-and-after-training data analysis was conducted using various statistical tests, including the independent sample t-test and paired samples t-test. In this analysis, skill development was the dependent variable.

2.5.2. Qualitative

For the verbal data of the focus group discussion, two researchers analyzed the data collected via the semi-structured interview and adopted the content analysis method. The three concurrent flows of activity data, namely, reduction, data display, and conclusion drawing/verification [60], were used.

3. Results

3.1. The Differences in Skill Development of Before-After Treatment

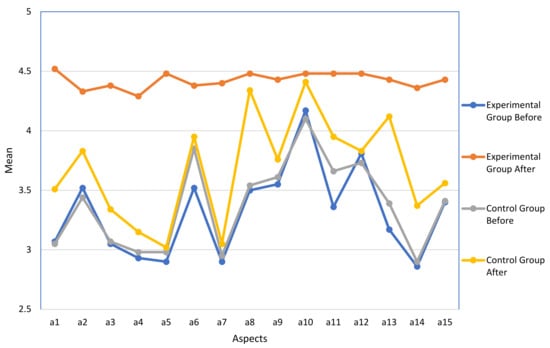

Table 1 and Figure 4 report the percent of increase in the comparison of mean scores obtained from the before–after treatment with respect to the features of skill development in the experimental group, i.e., the POTP group, and in the control group, i.e., the non-POTP group, as well as the results of the independent samples t-test.

Table 1.

Mean (M), Standard Deviation (SD), % Increase of Mean Scores of Skill Development, and Results of Paired Sample t-Test.

Figure 4.

Changes in the Estimated Means for Skill Development Before and After Treatment.

The mean differences in skill development before and after intervention were compared using a paired samples t-test (Table 1). With respect to the overall mean score of the experimental group, the paired samples t-test results indicated that the overall mean score after the POTP intervention (M = 4.42, SD = 0.44) was significantly higher than it was before the intervention (M = 3.31, SD = 0.35), t(41) = 12.429, p < 0.001. The % increase in the mean score was 33.49%. When considering each factor, it was found that all aspects of the experimental group exhibited significant improvement in skill at the end of the POTP intervention (p < 0.001 and 0.05). The top five means with the highest increase after completing the POTP intervention compared to the pretest for the experimental group were a5, Occupational therapy activities for psychosocial work (54.10%); a4, Exchange experiences with different disciplines and institutes (52.50%); Modern technology and classroom online platforms use (51.64%); a1, Ability to use online meeting program (47.29%); and a5, Occupational therapy for learning diversity (46.34%).

With respect to the control group, i.e., the non-POTP group, which was taught in a regular classroom, it was found that the mean pretest and posttest scores were significantly different (p < 0.05) in six aspects, namely, a1, Ability to use online programs such as ZOOM and Google Meet for teaching and collaborating; a2, Good personality and character building; a8, Plan for future teacher career examination; a11, Obtaining mentoring, encouraging, and inspiration for teaching as a profession; a13, Ability to reflect on the preservice teaching program for professional development; and a14, Ability to exchange preservice teaching program experiences with peers from different disciplines and different institutes. However, the maximum mean % increase of the control group was found to be moderate at 22.76%. Hence, the results of the paired samples t-test concluded that POTP treatment contributes significantly to the development of professional skills.

3.2. The Mean Differences of the Experimental and Control Groups in the Pretest and Posttest

Table 2 presents the results of the independent samples t-test that compared the means for the pretests and posttests of the two groups. Regarding the pretest scores, no significant differences between the means were detected (p > 0.05) for all categories except a11, Obtaining mentoring, encouraging and inspiration for teaching as a profession (t(81) = 2.224, p = 0.029). This result indicates that the randomization of participants into the experimental and control groups was relatively equitable.

Table 2.

The Results of the Independent Samples t-Test: Comparison of the Means of Skill Development between the Experimental and Control Groups.

With respect to the posttest scores, the results of the independent samples t-test demonstrate that the experimental group’s scores are statistically significantly higher (p < 0.05) than those of the control group in all aspects except a8, Plan for future teacher careers examination (t(81) = 1.014, p = 0.314), and a10, Fostering the spirit of being a teacher (t(81) = 0.473, p = 0.637).

3.3. Participants’ Satisfaction with the POTP

The results for each of the ten satisfaction aspects of the POTP format reveal fairly high to high levels of satisfaction (range 4.02 to 4.43) (see Table 3). There were no statistically significant group differences for any of the individual satisfaction factors.

Table 3.

Experimental Group Participants’ Satisfaction with the POTP (N = 42).

As presented in Table 3, the participants were highly satisfied with the training. All 42 experimental group participants who completed the post-training evaluation indicated that they were highly satisfied with the program (M = 4.22, SD = 0.62). When considering each item, the five items receiving the highest rankings were as follows: training contents are useful and appropriate (M = 4.43, SD = 0.50), knowledge of guest speakers is appropriate (M = 4.40, SD = 0.54), overall satisfaction (M = 4.38, SD = 0.54), suitability of program for educational programs at universities (M = 4.36, SD = 0.58), and clear program objectives and importance and duration of program, etc. (M = 4.24, SD = 0.62). The lowest scores were recorded for the following factors: training on Monday (M = 4.02, SD = 0.64), ten times per semester (M = 4.05, SD = 0.70), time period 19.00 to 20.30 (7 pm to 8:30 pm) (M = 4.05, SD = 0.66), and duration of 1.5 hours per class period (M = 4.14, SD = 0.70). As evidenced, the lowest scores were all concerned with the time and duration of the training.

3.4. Insights from Focus Group Discussion

There were eight experimental group volunteers (P1 through P8) who participated in the focus group discussion. The duration of this group discussion was one hour, and there were five interview questions. Conceptual analysis was used as the qualitative approach. All eight participants agreed that the program is effective and that they gained a new body of knowledge regarding educational technology issues, life and career aspirations, and preparation for future government teachers’ examinations as well as opportunities to continue study both in Thailand and abroad.

The responses obtained from the focus group discussion are as follows:

This is a very good program to improve my skills; there are many interesting topics such as how to use ZOOM, Google Meet, Google Form, ClassDojo, and Edmodo that are beneficial for the pandemic era that I want to know.(P1)

Especially all guest speakers are very knowledgeable, kind and friendly. I am very happy to participate, and I think this program is truly effective for me.(P1, P4)

I agree with them, and I am very happy to join this program. At first, I wanted to know how to use ZOOM and technology to enhance our teaching, and this program can fulfill my needs.(P2)

They all also revealed that the POTP program not only improved the professional skills of the PSTs, but it also enhanced their desire and confidence and encouraged them as they prepared for life and career opportunities.

I am always waiting to join this program when the time comes. I truly appreciate all guest speakers who truly inspire my future life and career, and I can share my dream with them too.(P3)

Normally, I always feel shy to share my dreams, but this program gives me the chance to speak out as well as provide useful information for me, such as a plan for continuous study and examination.(P5)

I also agree with them that this program has inspired and encouraged my dream that I want to be a government teacher and successful in my career and family life.(P7)

I plan to continue my master’s degree, and this program gives me the opportunity to continue my studies and know how to prepare.(P8)

When asked about the appropriateness of the training period, the answers were as follows:

The format is suitable, and we always got the reminder and call to ask us to join. Training duration of approximately 1.5–2.00 h a week is suitable, but sometimes in the evening Monday, we are tired after teaching.(P8)

It is possible to adjust to other times such as Friday afternoon if possible so we can push into the curriculum to continue development as a process of learning development skills, while practicing the strategies learned in PST program.(P4)

This program is appropriate for preparing preservice teachers in this era.(P1–P8)

Especially, the preservice teaching program of universities needs to provide more technology and English skills and teaching profession exam preparation because we want to know more to prepare and achieve”.(P1, P3, P5)

It is possible to apply in real practice such training programs for students and requirement activity development.(P1)

It will be good if we can embed into the curriculum and let all students join together because right now, we can use only online for the training program.(P4)

This is very convenient, but all participants need to have a good internet network, and then it will be effective.(P5)

All guest speakers and topics are great; it is sure to be useful in real application.(P6)

I love that we can learn and join online; that is very convenient for me.(P3)

Based on the responses, it can be concluded that the PSTs who participated in the POTP were satisfied and that this program is an effective online tool for enhancing PST programs during the COVID-19 pandemic era and into the 21st century.

4. Discussion

Based on the findings of this study, it can be determined that the POTP activities significantly improved the skill development of the PSTs in the experimental group. The highest achievement in the experimental group was noted for a14. Compared with the control group, i.e., the non-POTP group, the PSTs that received POTP training exhibited statistically significantly higher skill improvements, with the exception of a8 and a10, in which the two groups showed no significant difference in their mean scores. These findings are likely because the PSTs scored relatively high at the beginning of the intervention on these two factors, i.e., plans for future teacher career examination and the fostering of the spirit of being a teacher. This may also be because the appearance of ceiling effects in the experimental conditions exhibited smaller improvements after the intervention than did those of the low-rated traits in the pretest stage [61]. In other words, it may be possible that, during the three-month intervention period and the promotion of the education program, both groups of participants cultivated the spirit of being a teacher and planning for exams for their future teaching career. This is consistent with the findings of Peacock [62] that claim that teachers are supported in the spirit of being a teacher through the program. Furthermore, Romero-Tena et al. [63] state that teachers must manage their training plans and be able to position themselves in their future professional careers when such occupations require competitive examinations; therefore, every student teacher must prepare for employment [64].

Ultimately, this study has found that participation in the POTP resulted in improved performance with respect to the majority of the requisite skills. The reasons for this positive impact of the POTP may be that these modules were beneficial for the PSTs in the digital age, a careful SWOT analysis before the program was developed, or a detailed explanation of the learning goals along with guidance from the coaches was provided. It has been confirmed that coaching and training support the competencies of the PSTs required for their job [65,66,67]. According to the meta-analysis of Kraft et al. [68], Mok and Staub [28] and the literature review of Hoffman et al. [69] summarize the effectiveness of coaching practices for teachers’ pedagogical outcomes.

Moreover, the findings from these experiments are consistent with the qualitative analysis results of the focus group discussion, indicating that POTP is a capable and appropriate tool that can be used to improve teacher readiness for engaging in online teaching, learning, and training programs during the widespread COVID-19 pandemic. These results are consistent with the qualitative research of Mabalane [70], which indicate that the online intervention program before and during the WIL improves confidence, emotional readiness, pedagogic knowledge, and ability in several student-teacher tasks. Lachner, Fabian, Franke, Preiß, Jacob, Führer, Küchler, Paravicini, Randler, and Thomas [23] found that teachers must engage with technology and professional pedagogical content knowledge effectively.

However, online technology preparation for student teachers is necessary, a finding that corresponds with the study of Fraillon, Ainley, Schulz, Friedman, and Duckworth [16]. As ICT and online teaching–learning are important for enhancing teaching abilities and professional skills [25], POTP can be an effective tool for developing PSTs’ competencies with respect to enriching education programs that are consistent with the new 21st century national and global frameworks for teacher professional standards, practicums, and competencies. This, however, strongly suggests the need to prepare student teachers to become work-ready professional teachers and, as such, means there must be a focus on training and personalized learning in the development of core competencies and a focus on specific activities that focus on goals and self-development. Accordingly, the student-teacher curriculum should apply the POTP approach when training PSTs, given that the results of the study indicate that the POTP can improve those skills necessary for teacher competency, especially the “ability to exchange preservice teaching program experiences with peers from different disciplines and different institutes,” a factor that received a very high ranking among the PSTs who completed the POTP.

5. Conclusions

In this research work, a proactive online training program (POTP), which is based on work-integrated learning (WIL) and evaluation models, was developed for PSTs. In summary, this study showed that the PSTs who participated in the POTP significantly increased their essential competencies. In this sense, the POTP addressed and improved those skills that PSTs need during their preservice program practice. The traditional preservice program (non-POTP) did not officially provide an online training program that continually enhanced and updated necessary competencies that were required during the pandemic and that were necessary as the world continues to change. The POTP is a useful online tool for the continual introduction of new sets of skills, which is an important process as PSTs transition into more advanced and competent teachers, and as changes are contiually occurring with respect to attitudes, knowledge, ability, and skills. Thus, as the POTP can be a beneficial program for enhancing PSTs’ competencies, it should be embedded in the traditional PST program as an in-time online tool that offers a proven learning process and that creates outcomes according to the latest professional standards and 21st-century skills.

6. Limitations and Further Study

This study focused on fifth-year PSTs in their second semester, which was the last semester of their learning program. Therefore, the research design was created according to the limitations of the study time of the sample. In addition, measurements were made using only a five-point Likert scale to facilitate and reduce the stress of answering the online questionnaire. For future improvement, a rubric should be created, and background characteristics affecting learning outcomes should be studied. Additional limitations include no long-term follow-up of this training, which means that the sustaining of online learning outcomes is not assessed nor is it determined whether the changes in learning outcomes are effective and sustainable over the long term. Researchers should eliminate bias differences in activity level for the intervention that may be administered during the regular lecture period of the educational institution. Moreover, collecting more information on the socioeconomic and demographic backgrounds of participants would be informative for understanding their competencies and developing strategies to better enhance their professional skills. One of the key challenges for improving the effectiveness of PSTs is that the reach of online skill development programs must be broadened to promote the continued development of professional skills. Further research should consider the POTP approach to develop PSTs’ skills, and it may include a skills development needs assessment, importance–performance analysis (IPA), and expectations as guides to assess future essential skills needs of PSTs. In addition, future research should investigate whether the direct and indirect effects of other factors and online training as a mediating impact can support increased skill development. Finally, it would be interesting to study the application of social networking in developing professional skills, as this may be beneficial for developing and exploring PST deep learning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B. and B.K.; methodology, P.B. and B.K.; software, P.B. and B.K.; validation, P.B. and B.K.; formal analysis, P.B. and B.K.; investigation, P.B.; resources, P.B. and B.K.; data curation, P.B. and B.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.B. and B.K.; writing—review and editing, P.B. and B.K.; visualization, P.B. and B.K.; supervision, B.K.; project administration, P.B. and B.K.; funding acquisition, P.B. and B.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) (grant number วช.อว.(อ)(ภพ)/46/2564), the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) via the Program Management Unit for Human Resources and Institutional Development, Research, and Innovation (grant number B05F640220), and the Suranaree University of Technology (SUT) Research and Development Fund (grant number IRD2-202-64-12-12). The APC was funded by SUT and NRCT.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Suranaree University of Technology, under Application No. EC-63-90, for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Phra Udomtheerakun for facilitating data acquisition and research conduction.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Pokhrel, S.; Chhetri, R. A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. High. Educ. Future 2021, 8, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, J.M.-C.; Ching, G.S.; del Castillo, F.; Wen, T.-H.; Huang, Y.-C.; del Castillo, C.D.; Gungon, J.L.; Trajera, S.M. Perspectives on the barriers to and needs of teachers’ professional development in the Philippines during COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockee, B.B. Shifting digital, shifting context: (re)considering teacher professional development for online and blended learning in the COVID-19 era. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2021, 69, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlin, M.; Samarawickrema, G. A commentary on the criteria of effective teaching in post-COVID higher education. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2022, 41, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil, M. An efficient way of applying big data analytics in higher education sector for performance evaluation. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2018, 180, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.L.; Smith, S.J.; Frey, B.B. Professional development with universal design for learning: Supporting teachers as learners to increase the implementation of UDL. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2022, 48, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, B. Embracing the possibilities of disruption. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 1388–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavya, R.; Sambhav, S. Role of mobile communication with emerging technology in covid’19. Int. J. Adv. Trends Comput. Sci. Eng. 2020, 9, 3338–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jima’Ain, M.T.A.; Majid, S.F.A.; Hehsan, A.; Haron, Z.; Abu-Husin, M.F.; Junaidi, J. COVID-19: The benefits of informatiom technology (IT) functions in industrial revolution 4.0 in the teaching and facilitation process. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, T.; Safta, M.; Titirișcă, C.; Firtescu, B. Effects of digitalisation on higher education in a sustainable development framework-online learning challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyeye, B.; Ojih, S.E.; Bello, D.; Adesina, E.; Yartey, D.; Ben-Enukora, C.; Adeyeye, Q. Online learning platforms and Covenant university students’ academic performance in practical related courses during covid-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, S. Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2020, 49, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Competency Standards Modules: ICT Competency Standards for Teachers; UNESCO: Paris, Fance, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fauth, F.; González-Martínez, J. Trainees’ Personal Characteristics in the Learning Transfer Process of Permanent Online ICT Teacher Training. Sustainability 2022, 14, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chonsalasin, D.; Khampirat, B. The impact of achievement goal orientation, learning strategies, and digital skill on engineering skill self-efficacy in Thailand. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 11858–11870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraillon, J.; Ainley, J.; Schulz, W.; Friedman, T.; Duckworth, D. Preparing for Life in a Digital World. IEA International Computer and Information Literacy Study 2018 International Report; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Karo, D.; Petsangsri, S. The effect of online mentoring system through professional learning community with information and communication technology via cloud computing for pre-service teachers in Thailand. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, Z.; Anwar, H.; Luneto, B. Multimedia powerpoint-based arabic learning and its effect to students’ learning motivation: A treatment by level designs experimental study. Int. J. Instr. 2021, 14, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brame, C.J. Effective educational videos: Principles and guidelines for maximizing student learning from video content. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2016, 15, es6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butnaru, G.I.; Niță, V.; Anichiti, A.; Brînză, G. The effectiveness of online education during Covid 19 pandemic—A comparative analysis between the perceptions of academic students and high school students from Romania. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, C.; Flores, M.A. COVID-19 and teacher education: A literature review of online teaching and learning practices. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laksmiwati, P.A.; Adams, D.; Sulistyawati, E. Pre-service teachers’ readiness and engagement for online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rasch analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Intelligent Systems-ICETIS 2021; Al-Emran, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 299, pp. 326–340. [Google Scholar]

- Lachner, A.; Fabian, A.; Franke, U.; Preiß, J.; Jacob, L.; Führer, C.; Küchler, U.; Paravicini, W.; Randler, C.; Thomas, P. Fostering pre-service teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK): A quasi-experimental field study. Comput. Educ. 2021, 174, 104304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK): Confronting the wicked problems of teaching with technology. In Proceedings of the Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education International Conference 2007, San Antonio, TX, USA, 26–30 March 2007; Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education: Chesapeake, VA, USA, 2007; pp. 2214–2226. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A.R.; Murad, H.R. The impact of social media on panic during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iraqi Kurdistan: Online questionnaire study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedek, A. Digital transformation in collaborative content development. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2020, 9, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulla, K.; Winitkun, D. In-service teacher training program in Thailand: Teachers’ beliefs, needs, and challenges. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2018, 26, 1579–1594. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, S.Y.; Staub, F.C. Does coaching, mentoring, and supervision matter for pre-service teachers’ planning skills and clarity of instruction? A meta-analysis of (quasi-)experimental studies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 107, 103484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukkink, R.; Helmerhorst, K.; Gevers Deynoot-Schaub, M.; Sluiter, R. Training interaction skills of pre-service ECEC teachers: Moving from in-service to pre-service professional development. Early Child. Educ. J. 2019, 47, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Egert, F.; Fukkink, R.G.; Eckhardt, A.G. Impact of in-service professional development programs for early childhood teachers on quality ratings and child outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2018, 88, 401–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almonacid-Fierro, A.; De Carvalho, R.S.; Castillo-Retamal, F.; Fierro, M.A. The practicum in times of COVID-19: Knowledge developed by future physical education teachers in virtual modality. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2021, 20, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Teachers’ Professional Learning (TPL) Study: Design and Implementation Plan; OECD: Paris, Fance, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- MOE. Thai Qualifications Framework 1 (TQF1): Pedagogy and Educational Program (Four Years’ Program) B.E. 2560; Ministry of Education of Thailand (MOE): Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Koster, B.; Dengerink, J.J. Professional standards for teacher educators: How to deal with complexity, ownership and function. Experiences from the Netherlands. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2008, 31, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Toktamysov, S.; Berestova, A.; Israfilov, N.; Truntsevsky, Y.; Korzhuev, A. Empowerment or limitation of the teachers’ rights and abilities in the prevailing digital environment. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2021, 16, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOA. Alberta Education: Teaching Quality Standard; Government of Alberta (GOA): Alberta, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Makhmudov, K.; Shorakhmetov, S.; Murodkosimov, A. Computer literacy is a tool to the system of innovative cluster of pedagogical education. Eur. J. Res. Reflect. Educ. Sci. 2020, 8, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Soepriyanti, H.; Waluyo, U.; Sujana, I.M.; Fitriana, E. An Exploratory Study of Indonesian Teachers’ Digital Literacy Competences. Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 2022, 28, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W. A critical examination of ELT in Thailand: The role of cultural awareness. RELC J. 2008, 39, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.L. An exploration into Thai pre-service teachers’ views, challenges, preparation and expectations in learning to teach EFL writing. TESOL Int. J. 2021, 16, 112–142. [Google Scholar]

- MOE. Announcement of Thai Qualification Framework (TQF): A Bachelor’s Degree in Education (Four-Year Programs); Ministry of Education of Thailand (MOE): Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- TCT. Regulations on Teacher Professional Standards, 4th ed.; Teachers’ Council of Thailand (TCT): Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jamjuree, D. Teacher training and development in Thailand. J. Res. Curric. Dev. 2017, 7, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Raduan, N.A.; Na, S.-I. An integrative review of the models for teacher expertise and career development. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 428–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korucu-Kış, S. Preparing student teachers for real classrooms through virtual vicarious experiences of critical incidents during remote practicum: A meaningful-experiential learning perspective. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 6949–6971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khampirat, B. The impact of work-integrated learning and learning strategies on engineering students’ learning outcomes in Thailand: A multiple mediation model of learning experiences and psychological factors. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 111390–111406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billett, S. Realising the educational worth of integrating work experiences in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2009, 34, 827–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khampirat, B.; McRae, N. Developing global standards framework and quality integrated models for cooperative and work-integrated education programs. Asia-Pac. J. Coop. Educ. 2016, 17, 349–362. [Google Scholar]

- Bouwer, M.; Venketsamy, R.; Bipath, K. Remodelling work-integrated learning experiences of Grade R student teachers. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2021, 35, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khampirat, B. Relationships between ICT competencies related to work, self-esteem, and self-regulated learning with engineering competencies. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khampirat, B.; Pop, C.; Bandaranaike, S. The effectiveness of work-integrated learning in developing student work skills: A case study of Thailand. Int. J. Work-Integr. Learn. 2019, 20, 126–146. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, B.A.; Campbell, M. Reshaping work-integrated learning in a post-COVID-19 world of work. Int. J. Work-Integr. Learn. 2020, 21, 355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Groenewald, T.; Drysdale, M.; Chiupka, C.; Johnston, N. Towards a definition and models of practice for cooperative and work-integrated education. In International Handbook for Cooperative and Work-Integrated Education: International Perspectives of Theory, Research and Practic, 2nd ed.; Coll, R.K., Zegwaard, K.E., Eds.; World Association for Cooperative Education: Lowell, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Groundwater-Smith, S.; Ewing, R.; Le Cornu, S. Teaching: Challenges and Dilemmas; Thornson: South Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ulaş, İ. The Impact of ICT Instruction on Online Learning Readiness of Pre-Service Teachers. J. Learn. Teach. Digit. Age 2022, 7, 116–126. [Google Scholar]

- Florczak, K.L. Book Review: The Practice of Nursing Research: Conduct, Critique, and Utilization (5th ed.). Nurs. Sci. Q. 2005, 18, 365–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, N.; Grove, S.K. The Practice of Nursing Research Conduct, Critique & Utilization; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling, A. Research Methods in Health; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, K.E.; McInnis, K.J. Teachers’ and students’ perceptions of the active science curriculum: Incorporating physical activity into middle school science classrooms. Phys. Educ. 2014, 7, 234–253. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods; SAGE: California, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, C.M.; Kenny, D.A. Estimating the Effects of Social Interventions; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Peacock, M. The evaluation of foreign-language-teacher education programmes. Lang. Teach. Res. 2009, 13, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Tena, R.; Barragán-Sánchez, R.; Llorente-Cejudo, C.; Palacios-Rodríguez, A. The challenge of initial training for early childhood teachers. A cross sectional study of their digital competences. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Z.; Yan, J. A preliminary study on the career development path for higher vocational teachers of professional basic courses in the context of “double quality”. For. Chem. Rev. 2022, 66–76. Available online: https://www.forestchemicalsreview.com/index.php/JFCR/article/view/523 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Joyce, B.R.; Showers, B. Transfer of training: The contribution of “coaching”. J. Educ. 1981, 163, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtts, S.A.; Levin, B.B. Using peer coaching with preservice teachers to develop reflective practice and collegial support. Teach. Educ. 2000, 11, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S. Impacts of pre-service training and coaching on kindergarten quality and student learning outcomes in Ghana. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2018, 59, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, M.A.; Blazar, D.; Hogan, D. The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2018, 88, 547–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.V.; Wetzel, M.M.; Maloch, B.; Greeter, E.; Taylor, L.; DeJulio, S.; Vlach, S.K. What can we learn from studying the coaching interactions between cooperating teachers and preservice teachers? A literature review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 52, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabalane, V.T. Work integrated learning online enrichment intervention programme for student teachers. Int. J. High. Educ. 2022, 11, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).