Research on Open Practice Teaching of Off-Campus Art Appreciation Based on ICT

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Can students appreciate art outside of school through self-directed learning (SRL) and enhance their artistic interest?

- Based on ICT support, can students achieve good learning outcomes and teaching assessment requirements?

2. Related Backgrounds

2.1. SRL in the Distance Education

2.2. Aesthetic Education and Art Appreciation

2.3. Policy Background

2.4. Preliminary Research Results

2.5. The Purpose of This Research

3. Materials and Methods

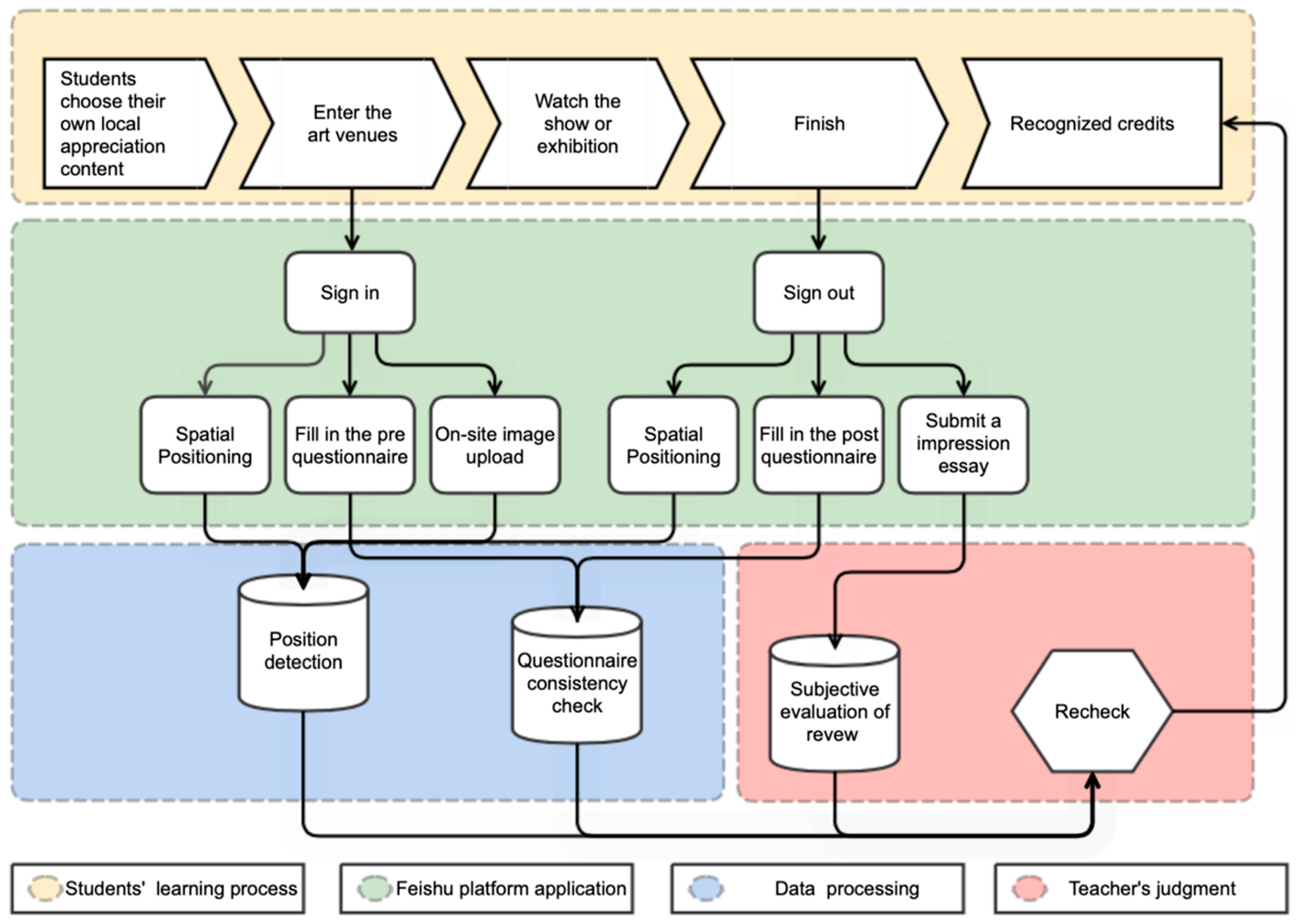

3.1. Experimental Procedure

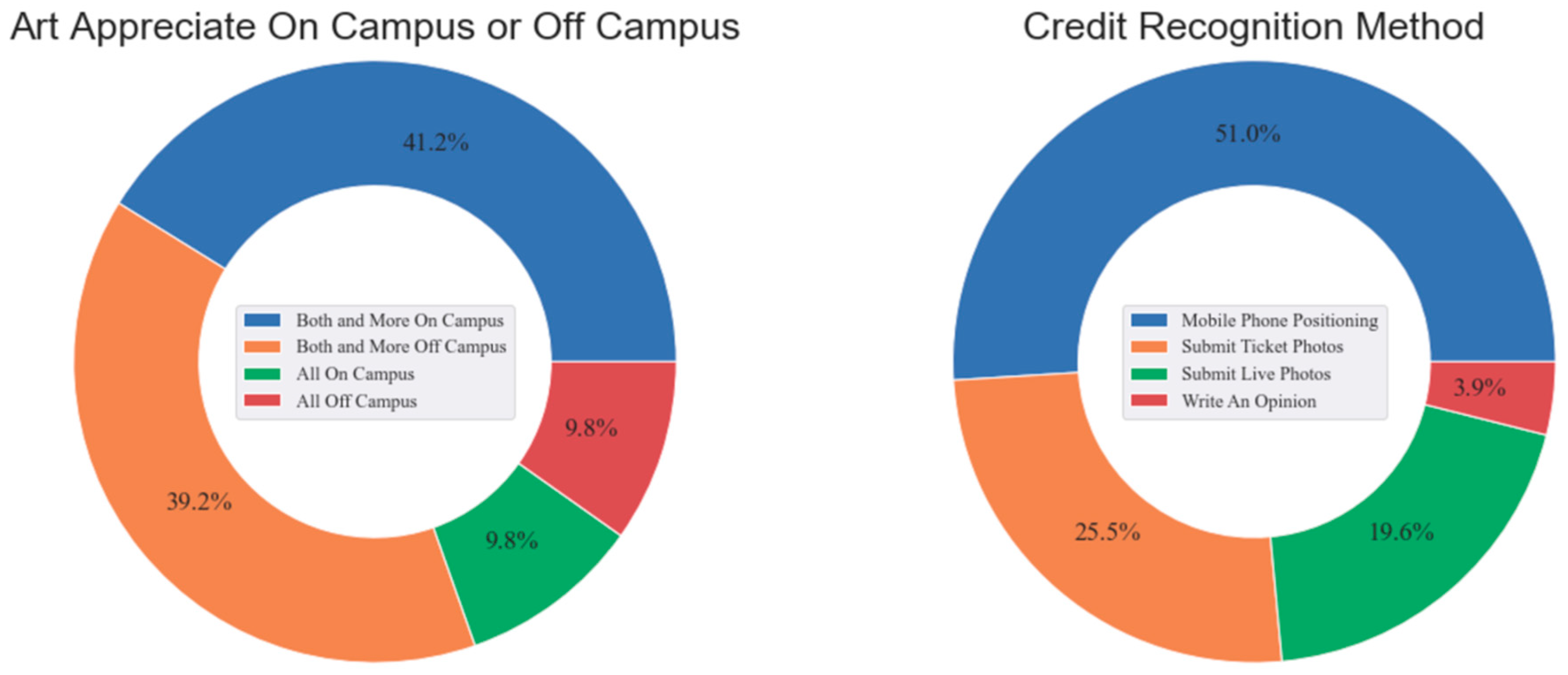

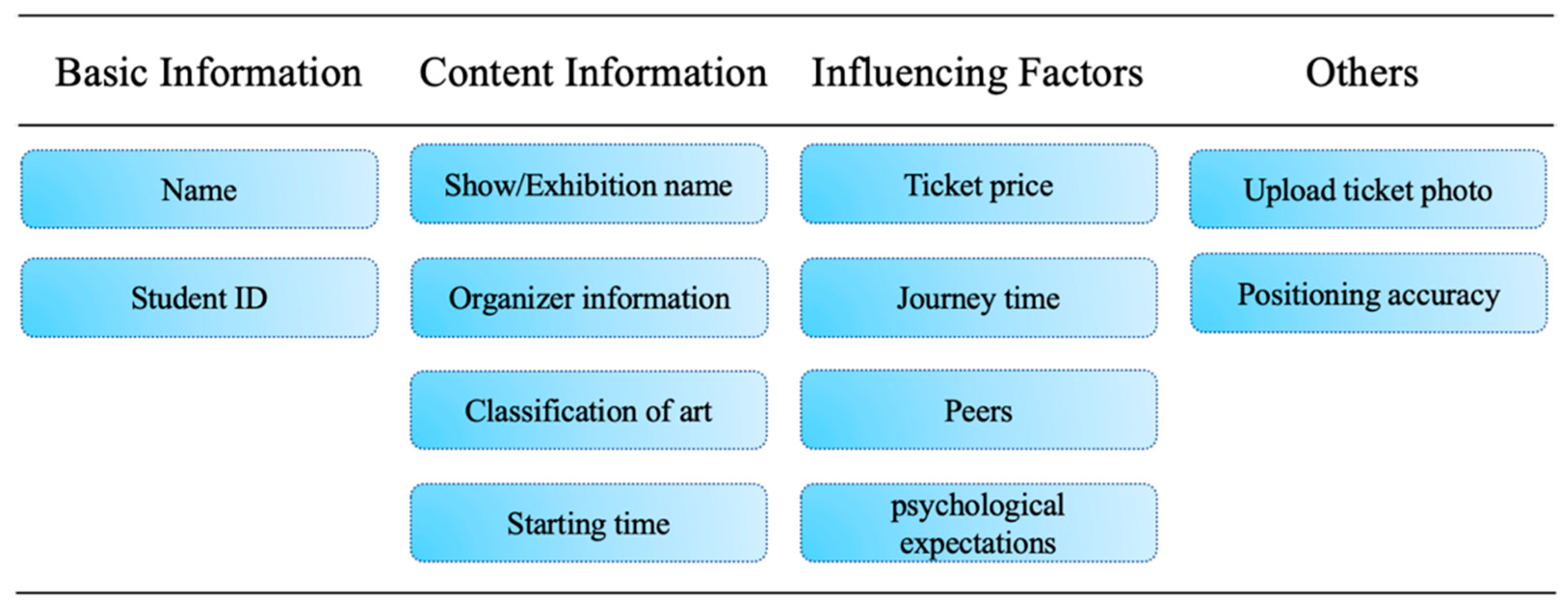

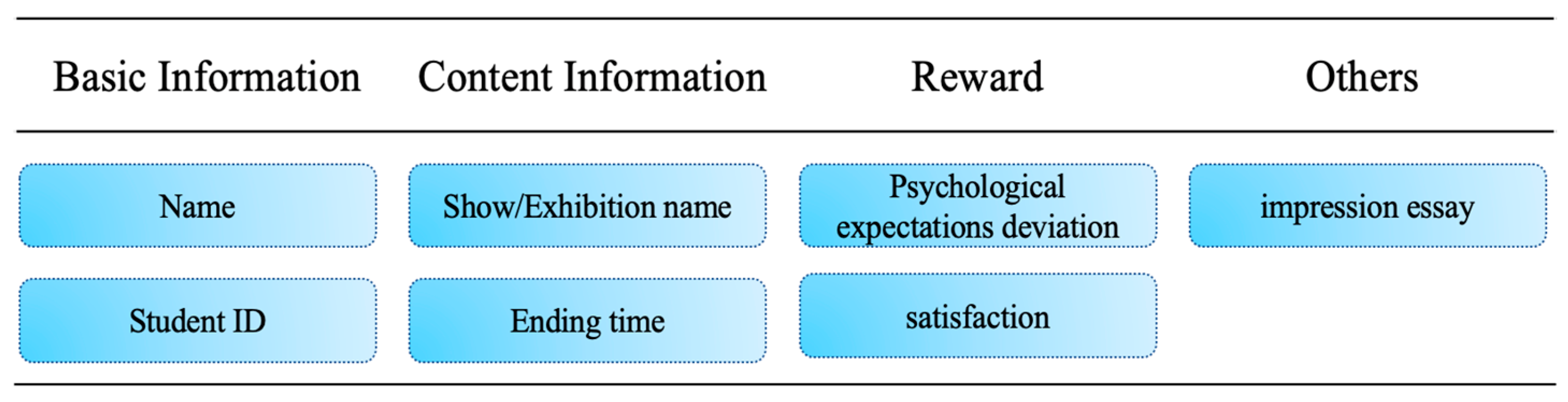

3.2. Mobile Positioning and Information Platform

3.3. Experimenter

3.4. Data Processing Method

4. Results

4.1. Experiment Results

4.2. Data Analysis Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eradze, M.; Bardone, E.; Dipace, A. Theorising on COVID-19 educational emergency: Magnifying glasses for the field of educational technology. Learn. Media Technol. 2021, 46, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, B.; Hogan, A. Pandemic Privatisation in Higher Education: Edtech & University Reform; Education International Research Pandemic Privatisation in Higher Education: Brisbane, Australia, February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hodaňová, J.; Hyksová, H.; Škultéty, M. Information and Communication Technologies in Educational Process. In Proceedings of the ICERI2020 Proceedings, Online, 9–10 November 2020; pp. 1714–1717. [Google Scholar]

- Corell-Almuzara, A.; López-Belmonte, J.; Marín-Marín, J.-A.; Moreno-Guerrero, A.-J. COVID-19 in the Field of Education: State of the Art. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agonács, N.; Matos, J.F.; Bartalesi-Graf, D.; O’Steen, D.N. Are you ready? Self-determined learning readiness of language MOOC learners. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 1161–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, S.b.; Ouahabi, A.; Lequeu, T. Remote Knowledge Acquisition and Assessment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Eng. Pedagog. (IJEP) 2020, 10, 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, S.; Ouahabi, A.; Lequeu, T. Synchronous E-learning in Higher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Vienna, Austria, 21–23 April 2021; pp. 1102–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Chancusig, J.; Bayona-Ore, S. Adoption Model of Information and Communication Technologies in Education. In Proceedings of the 2019 8th International Conference On Software Process Improvement (CIMPS), Leon, Mexico, 23–25 October 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhmudova, D.; Tadjibaev, B.; Dusmurodova, G.; Yuldasheva, G. Information and Communication Technologies for Developing Creative Competence in the Process of Open Teaching Physics and Maths. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2020, 24, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Jang, J.; Kim, J.; Paik, J. The Study on the Way of Art Appreciation and Education Program Using Principle of Perception and Eye Movement. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2016, 16, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Quesada, L.; Medina, C.S.; Sierra, D.; Bojorges, J. La Música como Estrategia Didáctica para el Fortalecimiento de los Niveles de Lectura una Propuesta Pedagógica. 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351019904_LA_MUSICA_COMO_ESTRATEGIA_DIDACTICA_PARA_EL_FORTALECIMIENTO_DE_LOS_NIVELES_DE_LECTURA_UNA_PROPUESTA_PEDAGOGICA (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Barnard-Brak, L.; Lan, W.Y.; Paton, V.O. Profiles in Self-Regulated Learning in the Online Learning Environment. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2010, 11, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.; Ogrin, S.; Schmitz, B. Assessing self-regulated learning in higher education: A systematic literature review of self-report instruments. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 2016, 28, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostroem, L.; Collen, C.; Damber, U.; Gidlund, U. A Rapid Transition from Campus to Emergent Distant Education; Effects on Students' Study Strategies in Higher Education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araka, E.; Oboko, R.; Maina, E.; Gitonga, R. Y Using Educational Data Mining Techniques to Identify Profiles in Self-Regulated Learning: An Empirical Evaluation. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2022, 23, 131–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myszkowski, N.; Zenasni, F. Individual Differences in Aesthetic Ability: The Case for an Aesthetic Quotient. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leddy, T.; Funch, B. The Psychology of Art Appreciation. J. Aesthetic Educ. 2001, 34, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funch, B. Art, emotion, and existential well-being. J. Theor. Philos. Psychol. 2020, 41, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, E.; Li, J. Constructing First-Class University and First-Class Discipline Classified. In Creating a High-Quality Education Policy System; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valsdóttir, K. Learning Journeys to Become Arts Educators A Practice-Led Biographical Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, D.-E. Online Art Education and Post Art Education Discourse—Case Study on Online Art Education. J. Res. Art Educ. 2020, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis, J.; Rodrigo, C. Open Educational Practices in Learning and Teaching of Computer Science. In Proceedings of the EDEN Conference. Process, Madrid, Spain, 21–24 June2021; pp. 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, A.; Huang, R.; Chang, T.-W.; Nascimbeni, F.; Burgos, D. Open Educational Resources and Practices in China: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admiraal, W. A Typology of Educators Using Open Educational Resources for Teaching. Int. J. Stud. Educ. 2021, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, J. Kano Model: An OS for Agile Leaders. In Great Big Agile; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 189–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardomuan, R.; Suryanegara, M. Analysis of the Need for Passengers’ Connectivity Aboard The Ship by using Kano Model. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Green Energy, Computing and Sustainable Technology (GECOST), Miri, Malaysia, 7–9 July 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, A.; Ebrahimi, S. Revising the interrelationship matrix of house of quality by the Kano model. TQM J. 2021, 33, 804–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Lin, R.; Wang, Z.; Cai, Y.; Wang, F. Curriculum Design of Art Appreciation in Colleges Based on Kano Model Demand Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Digital Society and Intelligent Systems (DSInS), Chengdu, China, 3–4 December 2021; pp. 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Mengjie, X. German Aesthetic Education from the Perspective of Phenomenology: Perception, Experience and Interaction. Explor. High. Educ. 2021, 74–80. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, A.H.K.; Hew, T.K.F. Information and Communication Technology in Educational Policies in the Asian Region. In Handbook of Comparative Studies on Community Colleges and Global Counterparts; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiu, A.; Bawa, K.; Saminu, S.; Zubairu, I. Application of Information and Communication Technology Facilities in Teaching and Learning Application of Information and Communication Technology Facilities in Teaching and Learning. In Emerging Trends in Contemporary Education A Book of Readings; Ahmadu Bello University Press Ltd.: Zaria, Nigeria, 2021; pp. 88–104. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351811380_Application_of_Information_and_Communica-tion_Technology_Facilities_in_Teaching_and_Learning_Application_of_Information_and_Communication_Technology_Facilities_in_Teaching_and_Learning (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Zimmerman, B. Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: An Overview. Theory Pract. 2002, 41, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seel, N.M. Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, R. Spatial-Positioning Technology. In Introduction to Geospatial Information and Communication Technology (GeoICT); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, N.G.; Shcheblyakov, E.S.; Farafontova, E.L.; Pugatskiy, M.V. The Use of Information and Communication Technologies in Education. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Economic and Social Trends for Sustainability of Modern Society (ICEST 2020), Krasnoyarsk, Russia, 20–22 May 2020; pp. 772–779. [Google Scholar]

- Moursund, D. Introduction to Information and Communication Technology in Education. 2005. Available online: https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/handle/1794/3181 (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Teräs, M.; Suoranta, J.; Teräs, H.; Curcher, M. Post-Covid-19 Education and Education Technology ‘Solutionism’: A Seller’s Market. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2020, 2, 863–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G.; Mantovani, F.; Wiederhold, B.K. Positive Technology and COVID-19. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, L.; Yudong, Z.; Hui, Z.; Weicheng, F. Accurate prevention and control of public health emergency and integrated management. Eng. Sci. China 2021, 23, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mickel, L. Performance practice as research, learning and teaching. Teach. High. Educ. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, J.; Lu, M.; Morton, Y.; Yang, Y. Introduction to the special issue on the BeiDou navigation system. Navigation 2019, 66, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Liang, J.; Ke, N.; Zhuang, L. Review on the Development of Indoor Positioning Technology. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2019, 9, 1072–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, H.; Xu, J.; Liu, C. Modelling and Simulation on Wireless Communication Positioning Technology in the Mall. In Proceedings of the 2017 29th Chinese Control And Decision Conference (CCDC), Chongqing, China, 28–30 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Liu, J.; Yin, Y.; Wang, W.; Hu, D.; Chen, P.; Niu, Q. Survey on WiFi-based indoor positioning techniques. IET Commun. 2020, 14, 1372–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petousi, V.; Sifaki, E. Contextualising harm in the framework of research misconduct. Findings from discourse analysis of scientific publications. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 23, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, P.; Conde-Jiménez, J.; Reyes-de Cózar, S. The development of the digital teaching competence from a sociocultural approach. Comunicar 2019, 27, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sova, R. Art Appreciation as a Learned Competence: A Museum-based Qualitative Study of Adult Art Specialist and Art Non-Specialist Visitors. Cent. Educ. Policy Stud. J. 2015, 5, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, A.; Fukushima, K.; Kawada, R. How Will Sense of Values and Preference Change during Art Appreciation? Information 2020, 11, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, P.; Lin, Z. Artificial Intelligence in Education: A Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 75264–75278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, H.E.; Gad, A.G.; Abohany, A.A.; Sorour, S.E. An Efficient Data Mining Technique for Assessing Satisfaction Level of Online Learning for Higher Education Students During the COVID-19. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 6286–6303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjabi, I.; Ouahabi, A.; Benzaoui, A.; Taleb-Ahmed, A. Past, Present, and Future of Face Recognition: A Review. Electronics 2020, 9, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Soleimani, F.; Irish, I.; Hosmer, J.; Soylu, M.Y.; Finkelberg, R.; Chatterjee, S. Predicting Cognitive Presence in At-Scale Online Learning: MOOC and For-Credit Online Course Environments. Online Learn. 2022, 26, 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sébastien Jacques, A.O. Distance learning in higher education in france during the COVID-19 pandemic. High. Educ. Policies Dev. Digit. Ski. Respond COVID-19 Crisis Eur. Glob. Perspect. 2021, 1, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Adjabi, I.; Ouahabi, A.; Benzaoui, A.; Jacques, S. Multi-Block Color-Binarized Statistical Images for Single-Sample Face Recognition. Sensors 2021, 21, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadbent, J.; Poon, W.L. Self-regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review. Internet High. Educ. 2015, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M.; Preckel, F. Variables associated with achievement in higher education: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 565–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croeser, S. Teaching Open Literacies. Cult. Sci. J. 2020, 12, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalova, T.I.; Tolstykh, O.M. Application of Information and Communication Technologies in Hybrid Learning of Engineering Students. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Quality Management, Transport and Information Security, Information Technologies (IT&QM&IS), Yaroslavl, Russia, 6–10 September 2021; pp. 677–681. [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez-Lopez, F.J.; Maurandi-Lopez, A.; Castejon-Mochon, J.F. Virtual Practical Teaching and Acquisition of Competencies in the Statistical Training of Teachers during Sanitary Confinement. PNA-Revista de Investigacion en Didactica de la Matematica 2022, 16, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.Z. Research on the Difficulties and Countermeasures of the Practical Teaching of Ideological and Political Theory Courses in Colleges and Universities Based on Wireless Communication and Artificial Intelligence Decision Support. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021, 2021, 3229051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus-Quinn, A.; Hourigan, T.; McCoy, S. The Digital Learning Movement: How Should Irish Schools Respond? Econ. Soc. Rev. 2019, 50, 767–783. [Google Scholar]

- Colás-Bravo, P.; Conde-Jiménez, J.; Reyes-de-Cózar, S. Sustainability and Digital Teaching Competence in Higher Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirin, S.; Vasojević, N.A.; Vučetić, I. Education Management and Information and Communication Technologies. In Proceedings of the 5th EMAN Conference Proceedings (Part of EMAN Conference Collection), Online/Virtual, 18 March 2021; pp. 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, G.; Carlson, A. Distinguishing intention and function in art appreciation. Behav. Brain Sci. 2013, 36, 153–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

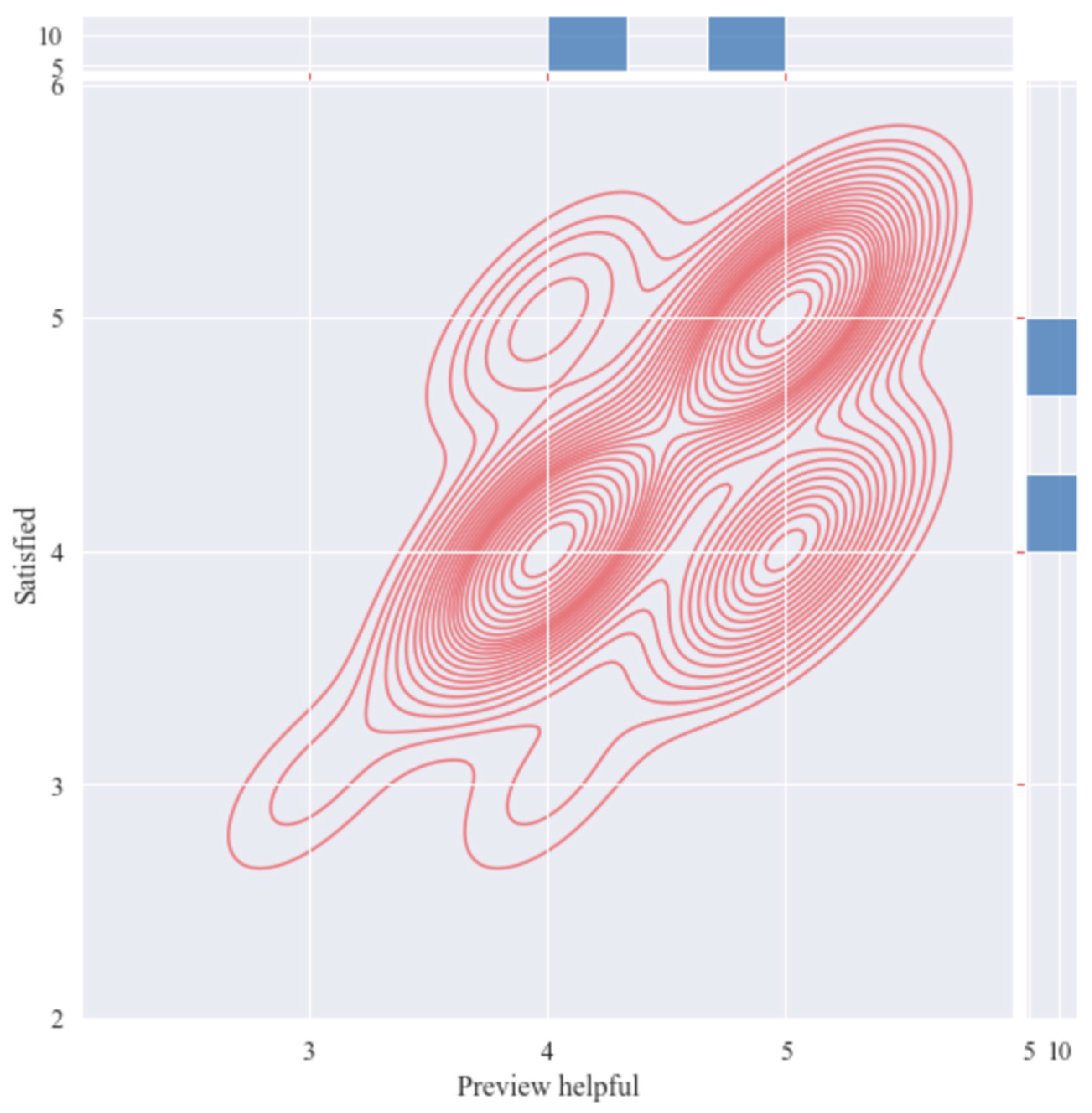

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item A | Increase interest | Psychological expectations | Preview helpful | Psychological expectations | Increase interest | Preview helpful |

| Item B | Satisfied | Satisfied | Satisfied | Peer | Psychological expectations | Psychological expectations |

| p | 1.89404582104268 × 10−7 | 3.14581603588882 × 10−5 | 1.87530180025815 × 10−4 | 7.43520014047949 × 10−4 | 2.33872682150937 × 10−3 | 2.90517692166116 × 10−3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, B.; He, B.; Wang, Z.; Lin, R.; Yang, J.; Zhou, R.; Cai, Y. Research on Open Practice Teaching of Off-Campus Art Appreciation Based on ICT. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4274. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074274

Song B, He B, Wang Z, Lin R, Yang J, Zhou R, Cai Y. Research on Open Practice Teaching of Off-Campus Art Appreciation Based on ICT. Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):4274. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074274

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Baoqing, Bingyang He, Zehua Wang, Ruichong Lin, Jinrui Yang, Runxian Zhou, and Yunji Cai. 2022. "Research on Open Practice Teaching of Off-Campus Art Appreciation Based on ICT" Sustainability 14, no. 7: 4274. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074274

APA StyleSong, B., He, B., Wang, Z., Lin, R., Yang, J., Zhou, R., & Cai, Y. (2022). Research on Open Practice Teaching of Off-Campus Art Appreciation Based on ICT. Sustainability, 14(7), 4274. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074274