1. Introduction

Companies tackle the grand challenges humanity is facing in various ways [

1,

2]. Some businesses across industries offset their carbon footprint or adapt their supply chains to source from local providers, while others adopt more operational practices toward sustainability [

3,

4]. The ambition of value-driven businesses is to make progress on the grand agenda to ensure the alignment of the business core values with the grand challenges faced by societies [

5,

6]. Value-driven organizations are guided by a set of core values shared among internal and external stakeholders [

7], which symbolize their identity, mission, and culture and can create and sustain a competitive edge [

8,

9]. Shared core values can also operate at the industry level, in the form of “macro cultures” where core values are shared across organizations [

10,

11,

12,

13]. While core values are the cornerstone of a sustainable business strategy and can serve as a platform to build consumer commitment and loyalty to an organization, they can also introduce challenges when an organization wants to evolve and consider new strategic initiatives [

14,

15,

16]. A decision to move towards an economic growth strategy may require changes in organizational values, which may conflict with the larger sustainability macro culture, and negatively impact social ties with the consumer and the community.

The craft beer industry is still emerging and growing, both nationally and globally [

17]. A challenge faced by many craft breweries as they aspire to expand operations to find more economic stability is to remain committed to their original core values. This challenge is amplified in an industry where social values are strongly embraced by consumers seeking creativity, small production, local identity, and anti-mass production [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Thus, small craft beer breweries aspiring to grow face a dilemma—to remain true to industry values while embracing expansion, without alienating core local consumers. However, we still know very little as to how organizations in general, and craft beer brewing companies specifically, resolve both growth and staying true to their industry macro values while maintaining relationships with their community as key stakeholders. Thus, this study examines: How can social and economic values be pursued in the craft beer brewery business?

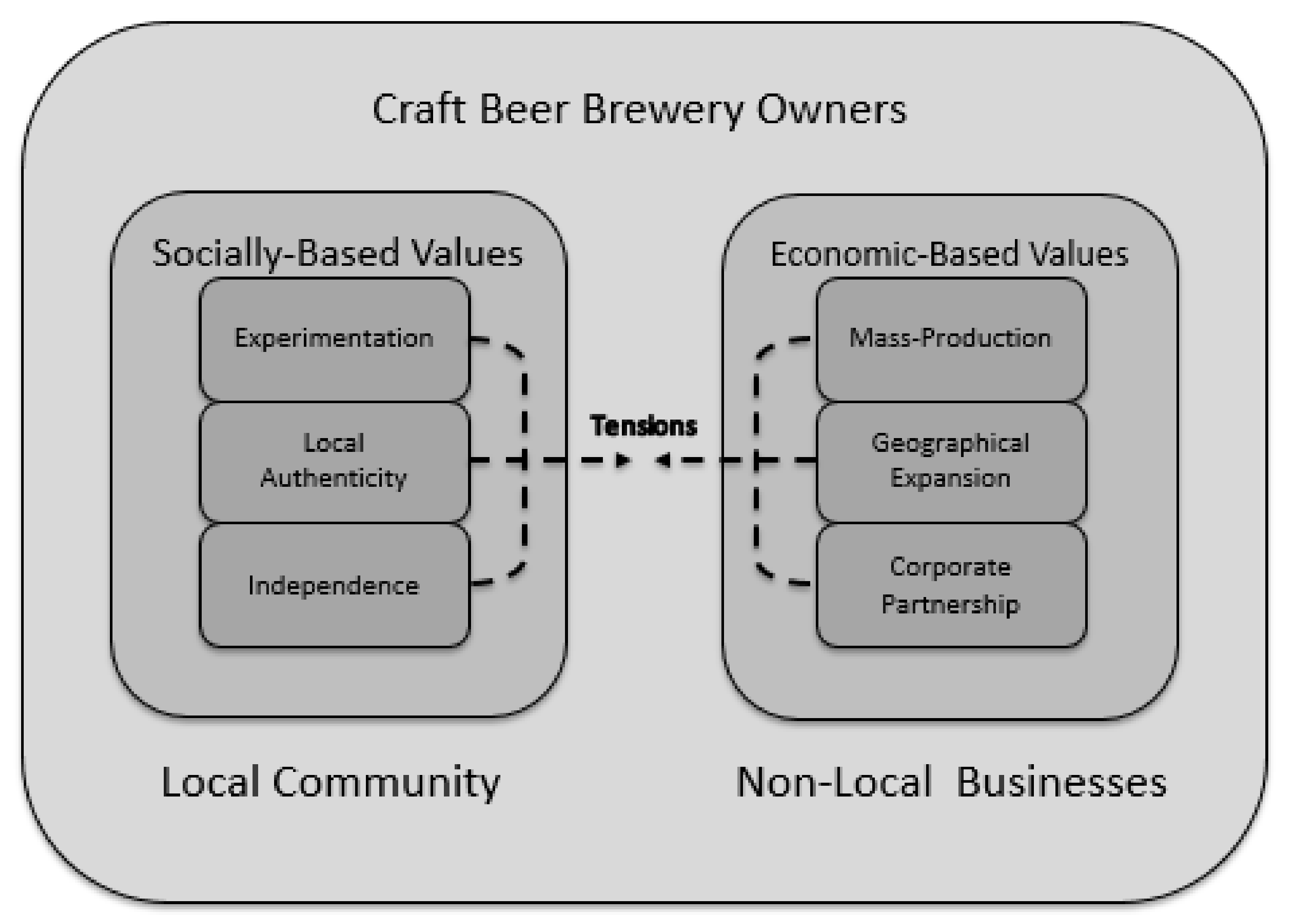

This article sheds light on the relationships with consumers and their local community, and on how organizations can involve consumers and connect with them in order to build long-term success through consistent shared organizational values. With an in-depth case research from six emerging craft breweries in Maine as context, this study takes a closer look at how sustainable business strategies can operate to reconcile conflicting values. Specifically, our exploratory study reveals tensions between experimentation, authenticity, and independence rooted in a socially based macro culture, on the one hand, and mass production, geographical expansion, and corporate partnership for economic growth, on the other hand. Our findings demonstrate the importance of working at a local level in order to successfully pursue non-local economic growth and reconcile profit business demands and longer-term sustainability and social value aspirations.

2. Background and Motivations

The interest in the causes and consequences of corporate social responsibility (CSR) has grown significantly over the past few decades. Here, CSR reflects a general orientation toward corporate decision making in which firms have not only a financial responsibility, but also a legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibility [

22]. Much of the research on CSR has been developed from a stakeholder perspective whereby qualities of moral worth are attributed to firms with a positive reputation for social responsibility [

23]. Specifically, the stakeholder perspective argues that some consumers feel more attracted to firms with a reputation for social responsibility, which increases market opportunities and can result in increased demand or paying a premium for the firm’s products [

24,

25]. In other words, firms in highly competitive industries can utilize CSR as a differentiation strategy to build relationships with stakeholders and create a competitive advantage [

26,

27].

The majority of CSR research has focused on larger firms, with less attention given to SMEs; however, there is mounting evidence that SMEs are increasingly using CSR practices to differentiate their products and promote growth [

28,

29,

30]. Recent research in the craft brewing industry suggests that brewers attempt to utilize CSR but struggle to communicate these accomplishments to their customers [

31,

32]. Perhaps the most prevalent way firms communicate their values to their customers is through their mission, vision, and core values. In this study, we seek to better understand a set of core values that SMEs (craft brewers) could focus on as a means of differentiating their products from those of their larger competitors (large brewers).

Framing the discussion within the context of sustainability, organizations have traditionally embraced and fostered core values from within the boundaries of the organization [

33,

34,

35,

36]. However, responsible organizations are increasingly emphasizing the importance of their relationships with external stakeholders interfaced through shared values [

37,

38]. In recent years, consumers, as key external stakeholders, have become more active, connected, and informed [

39], and their loyalty is often based on corporate values [

40]. Social values are increasingly used as a platform to connect with consumers to communicate what the company believes and pursues—often framed within social issues such as corporate social responsibility, environmental and social governance, sustainability, business ethics, and equality.

Organizational values can play a key role in fostering but also alienating consumers as key external stakeholders. Stakeholder theory points to the importance of keeping an active and open pathway with a range of external stakeholders, as they can have a real impact on businesses’ success [

7,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Wheeler and Sillanpa (1998: p. 203) [

45], in their framing of organizations as “the stakeholder corporation”, made a convincing argument regarding the importance of listening to an organization’s external stakeholders as an inclusion strategy based on ongoing dialogues to align values. Further, they argue that “values which are articulated top-down, or which are cast in tablets of stone are by definition non-inclusive and will inevitably become ossified”.

Some companies in the food and service (F&B) sector have succeeded by staying committed to their original values. For example, Ben and Jerry’s (B&Js), a value-driven organization, have successfully incorporated social, environmental, and corporate justice values into their brand. Their early success was a strong commitment to its consumers based on shared social values (e.g., same-sex marriage equality). The company was sold in 2000 to the food giant Unilever, and many followers believed that these values, along with B&Js’ identity, would not survive, causing original fans to turn away from the brand. Yet, B&Js has succeeded, in part based on successfully seeking and winning B Corp. certification status in 2012. Moreover, the success has also been attributed to the independent board of directors, which is responsible for the social mission, integrity of the brand, and wage settings in factories (Jostein Solheim, CEO).

Socially-Based Values

The importance of involving external stakeholders is likely a function of the strength of the organization and, by extension, of industry values, in the form of macro cultures [

10]. At its roots, the craft beer industry is characterized by three closely related core values, that also help distinguish it from mainstream large-scale beer breweries: creativity and innovation (through the small scale), authenticity, and independence (commitment to community) [

46]. First, while there are only four main ingredients in beer: water, yeast, hops, and some form of grain, there are virtually endless combinations of flavors that can be added and innovative brewing techniques. Craft beer brewers are very much driven by experimentation and exploring new styles, and there are currently over 150 styles of craft beers, and more are continually emerging as crafter brewers continue to explore [

47,

48,

49]. Most brewers started as hobby-brewers learning through trial, error, and an interest in experimentation and creativity. Innovation is also heavily linked with the production process and method—for example, exploring new ways to ferment and flavor beer (e.g., adding fruit, extracts, and different varieties of hops and yeast strains) that continue to generate new flavors and types of craft beer [

47]. Keeping the operations small allows for low-risk experimentation in small batches, trial and error with little waste and financial loss, and quick feedback from local patrons. This is in stark contrast to large breweries, which make little changes to their core beers to scale and maintain a consistent beer. Second, authenticity is linked with the notion of (hand) craft, where the value lies in artisanal production, rather than mass-produced beer, which is viewed as fake by many craft beer enthusiasts [

21]. Authenticity allows for variability (not homogeneity) and aims to counter the mass production, industrialization, and dominance of a few powerful large-scale brewers, in a David-Goliath sense.

Finally, the importance of independence is influenced by the neo-localism movement—increased demand for products with strong links to the local community [

18,

19,

20,

50]. This movement has been noted in related industry segments including restaurants, food, grocery, and agriculture (i.e., farm to table), framed within the broader sustainability movement. Some argue that neo-localism provides a local community with a means to reaffirm its identity by choosing locally sourced and produced beer [

20]. Within this movement, there is also an interest to support local businesses, and research suggests that small local craft breweries can help revitalize and support sleepy rural towns. The connection between the local community and craft brewery founders has been noted as a key factor for the survival of craft beer breweries. For instance, nine out of ten professional brewers have roots as homebrewers (Brewer Association), which further links the brewer-community together, as the brewmaster often has kinship ties in the local community.

The three core values of small scale, authentic craft, and independence are symbolized by unique specialty beers through small batches crafted and sold locally in the same building, in taprooms where the brewmaster engages with local patrons on a first name basis [

46,

51,

52]. These core industry values resonate and are generally embraced by the local community patrons, which are further reinforced by compelling start-up stories about the humble beginnings of the brewery, on a shoe-string budget, starting in the founder’s kitchen [

19].

A recent 2020 report by the Brewer Association shows a decrease in the number of opening breweries and an increase in the number of closing breweries [

53]. Organizations’ decisions to expand their operations while trying to maintain a key market share is becoming more pressing in competitive markets, trying to move away from a single “either/or” strategy approach to an “and/also” multi-strategy approach [

44,

54]. However, we still know very little as to how organizations in general, and craft beer brewing companies specifically, resolve both growth and staying true to their industry macro values while maintaining relationships with their community as key stakeholders. By using the emerging craft beer industry as context, this study takes a closer look at how companies build long-term success through consistent shared organizational values.

4. Findings

Our findings reveal several conflicting challenges between three pairs of core values: (1) experimentation–mass-production; (2) local authenticity–geographical expansion; and (3) independence–corporate partnering. We further unpacked these managerial tensions that operated within both social and economic values.

4.1. Experimentation–Mass-Production

First, a focus on experimentation involved a localized emphasis by engaging customers in idea generation and feedback through both informal knowledge exchange (in taprooms) and formal channels (i.e., open house brew days and brewing competitions) to maintain a commitment to novel and creative brewing. One brewmaster commented: “We have plenty of homebrewers coming by with samples. They want feedback on how to improve it and we get ideas for new flavors”. A customer explained: “I love going to the taproom and know that there will be something different on tap for me to try. That’s why I go there. And the fact that John [the brewmaster] stands on the other side of the counter pouring is great and I can have a conversation about the latest brew”. Another brewmaster commented on the role of the open house: “We have open brew days to invite people to come and see the operation and how we brew. People love the access and we build a relationship with our community”. Moreover, experimentation could also involve a collaboration between craft breweries and customers. For example, during amateur craft beer competitions, typically arranged by a craft beer club, winners had the opportunity to collaborate with a local professional to create a new craft beer (i.e., Pro-Am collaborative brew), as one amateur brewer explained:

“It was really cool, I got to work with a brewery, we sat down and talked about our ideas and then got to work using the brewer’s [brewing] system. I didn’t get any money, but I learned a lot and got to know the brewer. And of course, I had bragging rights [laughing]”.

In contrast, while creating new beers was important, all craft breweries we interviewed were considering expanding their operations. A key reason was simply to be able to keep up with consumer demand, yet it seemed to change the nature of work, as one brewmaster commented on the tensions of going from small-scale production to mass production:

“We used to can and label by hand. It was cool in the beginning; you had a hand in everything included in the beer making. But as our production grew and added machines for bottling, canning, label makers, and packing machines, you’re losing the feel and connection with the product, and now it’s mostly mass-produced. But we still do some hand-made stuff—like for special brews or aged ones, we use non-standard bottles that don’t fit in the machine. Our locals love it”!

Another reason was to expand and market its most popular craft beers, often referred to as their “flagship” beers, for distribution beyond local consumption. When probing a brewmaster on the importance of flagship beer: “It was the beer that really pushed me to go pro. All my friends said, this is excellent, and people here would pay for it”. Flagship beers seemed key for growth. Craft breweries generally offered three to four experimental craft beers that they rotated once a batch was sold out. However, all breweries tried to have their flagship beers, which they had perfected over time, always available. One brewmaster explained:

“We have perhaps five or six variations of our pilot beers that we test and tweak in order to perfect them. Once we are happy with it, we scale it and mass produce it. But it has to be right and we need to make sure it can hold up in cans [for aging on the shelf in grocery stores] without turning bad”.

Seeking growth meant that brewers needed to expand their production, which meant that their original location had to be expanded. A few of the brewers had recently bought additional facilities to allow for scaling their production. As one brewmaster explained:

“Brewing is a very space and labor intensive thing, we need lots of room to add barrels and a bigger brew system to make more beer. And we had to reconfigure the landing dock to make it easier to move the grain bags with a forklift; lifting those bags by hand was a killer. But we need to keep our original taproom—that’s where our customers expect to have our fresh beer”.

Others have expanded their original location by purchasing adjacent land to add brewing capacity, parking spaces, and outdoor seating, to maintain the same location for all brewing operations. Interestingly, growth aspiration seemed possible with an ambidextrous production strategy of small-scale novel beer along with large-scale flagship beer. That is, as long as small batches and creative new offerings were still part of the core values, local customers approved the economic interest for growth. One customer explained: “Well, as long as they are still producing new cool beers and I get the local vibe, I could care less that they are trying to get bigger. Good for them that they are selling good beer and have a high demand for it”.

Thus, our fieldwork shows a dual focus on both staying true to creativity and expanding production on a few flagship beers. Owners and brewmasters clearly made efforts to explore and innovate, to offer innovative beers, and to create and maintain strong social ties with local patrons and up-and-coming home brewers. At the same time, mass-production was pursued based on increased demands, perfecting and scaling operations to produce flagship beers that also served as an identity of the craft brewery.

4.2. Local Authenticity–Geographical Expansion

A second theme involved the tension between maintaining authenticity while pursuing a geographical expansion beyond the initial local market. Our fieldwork indicated efforts to embrace local meaning and a sense of place in a range of ways. For example, incorporating names and places with local significance for new beers, company logos, and beer flavors; as one brewmaster explained:

“Our brewery has its roots here in the local community; this is where it all started. Our name [of our brewery] indicates where we are, if you look at our company logo, you will see elements that symbolize significant meaning to all our local patrons; our beers often are named from local places like islands, pictures of Maine stuff, names of rivers, lighthouses, outdoorsy stuff, it communicates who we are and where we are from”.

Another customer commented: “It is important to stay true to the craft, I’m not a big fan of buying supermarket beer, the beer I buy in this place has meaning to me, I know who made it, I can relate to the name of the beer, and I feel like I’m part of this place”. Another customer commented: “It’s important to me to support real people. If I buy a beer here, I know that some of this money goes straight into the pocket to the guy pouring me the beer. I really don’t care for mega breweries that are all about profit and paying someone that has no clue how to make an IPA. This brewery really cares about making beer that locals want. Money doesn’t seem like a priority”. Authenticity was further emphasized by maintaining the focus on small batches of experimental flavors, aged in various wooden casks, and hand-canned beers, as explained by one brewmaster:

“It’s important that we keep trying new things. We make some really cool beer that we age in our casks that were originally used for making whiskey. We can’t really make much money of these batches, the volume isn’t there, they are gone in a few days, but it keeps things interesting, and our locals really love the artisan process”.

During our interviews with owners and brewmasters, we quickly became aware that all breweries were seeking to expand and grow beyond the local market. The desire for geographical expansion was due to a need for economic stability and survival. When pushing on this theme, brewers made the point that expanding production was needed to allow others beyond the local community to enjoy their beers. One owner explained the importance of non-local distribution through flagship beers: “When tourists come here during the busy season [summer], they get familiar with our brand and hopefully they fall in love with our beers and will look for it once they are back home. We need our tourists to keep drinking our beer when they go back home”.

At the same time, the importance of local meaning and a sense of place was also used as branding and marketing tools to expand distribution across states, as explained by another owner:

“Let’s be honest, Maine as a brand sell. We just got back, the both of us [owner and brewmaster], from the Great American Beer Festival in Denver a couple of weeks ago, and we were both very surprised by the volume of people who came up to our booth who had a connection to Maine and wanted to taste. We see a lot of breweries along the coast using lobsters, lighthouses, and boats on their beers [logos], we use moose in our brand and labels. Selling local stuff at a non-local venue works; it’s like they feel like they travel to Maine by opening the can of beer and get a taste of it—literally”.

Interestingly, the goal of geographical expansion through local authenticity seemed to resonate and was embraced by local customers; one of them explains,

“I think it’s cool that we show people [from out of state] what we are about, we are proud about what this state is about, we are hard workers, great snowy winters, and beautiful warm summer, I feel proud when I see these things [on the label] on the beer”.

In sum, both breweries and local consumers seemed to understand the value of a dual focus on local authenticity and geographical expansions. On the one hand, owners and brewmasters were able to grow and showcase their locally inspired craft beers beyond their immediate local market, helping to drive out-of-state sales. On the other hand, the local community still felt connected and able to keep consuming creative craft beer. For example, consumers seemed to build stronger social ties and meaning with the local brewery, as they felt connected and part of a community’s local history, location, culture, and sense of place even as it continued to grow in non-local markets.

4.3. Independence–Corporate Partnership

The final theme discovered in our fieldwork involved tensions between the desire to operate independently and the need for expansions through partnerships beyond brewery boundaries.

Independence seemed driven through social community commitments. It was evident that a brewery owner wanted to run its business, keep the flow of innovative beer, and maintain its emphasis on local consumers. Our interviews suggest that the owners and brewmasters seemed very keen on maintaining an operation that allowed for freedom and the choice of when to open, what to offer, and how it was delivered. One owner explained: “We make sure that we’re in charge of how we do things around here. Even if we have bank loans to pay, we are in charge to brew beers that we think will taste good and our customers to enjoy”. This was further supported by various consumers; as one explained:

“The thing about craft beer is that it’s fresh, new, and different. If I want to get the same stuff, I can just go and get supermarket beer. I feel that what I drink [at the tap room] influences what they will make next time. I like the idea that we [customers] have a say in what is brewed, not some corporate dude”.

The importance of independence was further emphasized by the social presence, as another owner explained:

“We try to maintain our local feel by creating local taprooms, it allows us to keep an ear to what our community wants to drink, they like to come and hang out and connect with our staff, and we switch our beer a lot based on what our patrons want to drink”.

Moreover, self-distribution further supported the notion of valuing independence. The ability to offer beer straight from the production room not only saved the owner money, but also maintained the breweries’ choice as to what beer to make.

However, the need for independence and self-distribution created challenges for growth in non-local markets, as one owner explained: “You have to be careful about how you go about growth and partnerships. You don’t want to come across as a ‘corporate-sell-out’, to your loyal local fans. You might upset those who drink our beer because they reject mass-production and want to support the little guy”. Moreover, flagship beer was distributed through third-party distributors, which required a consistent flavor, a quality suitable for longer-term storing, and volume. This allowed for non-local distribution, as explained by one brewmaster:

“It’s helpful to be able to partner with a distributor, it gets our beer out there and we don’t have to deal with trucks and drivers. We focus on our beer, which is what we are good at, and the distributor helps put our beers on the shelves. But we do need to increase our production to meet our agreement, we need to make sure we always have enough beer for the distributor. It creates some pressure on us and it’s pretty repetitive”.

Another owner elaborated further:

“Our local stuff that we self-distribute is more fun, we can be creative and explore things. But the beer we send to the distributor has to be perfect—it’s our brand out there, and if it’s not up to snuff, it will hurt us. But our local guys [consumers] expect experimental stuff, and they get it and enjoy having the first try”.

Interestingly, while taprooms supported the local feel and self-distribution, they also served as a marketing mechanism for tourism and a platform to engage out-of-state consumption and needed distribution through formal business contractual agreements with distributors and wholesalers, as one owner explained:

“Our taproom is a great marketing tool, when tourists come, they try our products, and the more of a local feel we have, we think it helps our beer sales out of state. They love the Maine feel. So we need to make sure we always have our core beers [flagship] because that’s what we offer out of state, especially during the busy summer times”.

The notion of business partnership seemed acceptable to local customers as long as a personal connection and local roots were maintained, as explained by one customer:

“I think it’s kind of cool that they [the brewery] sell this beer out of state. Whenever I go to a bar in Boston, I look for it. But I don’t feel they are like the mega beer companies just because they sell out of state. It’s still a craft beer company that always tries to offer new stuff, and I know it starts at home, where we get to try it first”.

In sum, our final themes of independence and corporate partnership seemed to operate in conjunction with one another. Offering creative small batches distributed locally while at the same time engaging in mass-producing flagship beers through distribution and agreements with retail stores created a dialectical relationship between independent flexibility and contractual obligations. Moreover, the physical location served both local and non-local expectations for both exploration and exploitation.

5. Discussion

Although many firms have aspired to balance social and economic values for years, not much was known about the causes and consequences of CSR until the past few decades. Much of this progress can be attributed to the contributions of stakeholder theory in describing precisely how and why CSR may contribute to a firm’s social and economic performance. This paper draws on the stakeholder perspective, with moral and social underpinnings for responsible innovation, to describe how craft beer companies utilize CSR to disrupt an industry dominated by large-scale brewers, by emphasizing the values important to their stakeholders.

From a stakeholder perspective, a primary driver of the adoption of CSR practices is the institutional pressure from outsiders (i.e., stakeholders). More recent research suggests that large firms and small firms experience different institutional pressures from separate stakeholders. Specifically, larger firms are driven toward CSR by entities such as shareholders, media, or government regulation; on the other hand, most small firms are driven toward CSR via the desire to build social capital with the local community (1–3). In other words, for SMEs, the use of CSR can enhance customer engagement, which leads to enhanced customer loyalty, word-of-mouth advertising, and customer feedback (4). Additionally, innovation is an important factor in understanding the relationship between social and firm performance [

62,

63]. That is, firms are most successful in converting social performance to financial performance when they use CSR as a means to innovate and disrupt the status quo.

Along these lines, we find that craft beer companies disrupted the traditional mainstream large-scale beer breweries by attending to their patrons, local roots, and social creativity, before pursuing economic values. Values-driven organizations with a strong sense of purpose are increasingly trying to build and foster relationships with external stakeholders through social ties to reach economic goals [

64]. Much of the focus on external stakeholders such as suppliers, competitors, the government, and unions have been heavily researched [

14,

15,

16,

65]. However, customers and their communities have received much less attention.

Organizations need to establish some basic definitions about their core values to ensure that “people know what they’re talking about and what they’re trying to accomplish” [

66]. Consumers are more informed and often vote with their dollars based on what the company stands for (i.e., Social Values). Engaging with consumers can be critical for a business, especially in industries founded on broad macro cultures shared by both businesses and their local community. This is also occurring among small businesses that have strong ties to local communities.

The present study expands on this research by examining how both social and economic values can co-exist. Our findings show a complex relationship between industry (social) values and business (economic) values. Specifically, our fieldwork suggests that craft breweries try to reconcile this dilemma through a multi-level dynamic business model that fulfills dual goals at both the local and non-local levels outlined in

Figure 1. While our model suggests three distinct sub-values, in practice (and typically for qualitative research) they are not mutually exclusive and necessarily overlap. For example, exploring flavors and ingredients is closely linked with the desire to signal local culture and meaning, and made possible by maintaining, at some level, the ability to control when and what to brew. Similarly, the scaling operation capacity and revenue is tied to expanding sales in non-local markets and further supported through third-party partnerships with distributors and retail stores. We further flesh out our theoretical contributions by grounding them in stakeholder theory and responsible innovation research.

5.1. Responsible Innovation

Stakeholder theory generally follows a strategic, moral branch [

67]. The premise of this theory in practice is a focus on non-economic values before bottom-line financial thinking. For example, Merck & Co., a pharmaceutical company, discovered a treatment for river blindness (through its medication Mectizan). After realizing that the only patients that suffered from river blindness, caused by a parasite, were poor rural citizens in central Africa, Merck decided to provide the drug for free, indefinitely [

68]. Our study shows that craft breweries pursue both—combining both social and economic gains in a micro-macro or local-non-local in a dialectical sense [

69]. That is, economic gains cannot be achieved unless social gains are pursued as well. The key for this paradox to succeed is involving and engaging their core followers. Stakeholder theory research shows that stakeholders are more accepting when they perceive the process to be fair [

23]. Moreover, stakeholder theory assumes a need to treat all players equally. Extending this logic, we observed that local breweries were more accepting of growth and expansion if they also perceived a link between their core social interests and the involvement with local customers, competitors, and other stakeholders.

Like other value-driven organizations, craft breweries face a fundamental tension between remaining faithful to local values and seeking non-local economic growth. Small firms rest on a set of social values that underpin the emphasis on experimentation in the craft, maintaining a local authentic feel, and being independent of the influence of large businesses. However, from a business perspective, breweries that aspire to expand are re-investing in their production facility, expanding sales to non-local markets by partnering with external business entities.

Responsible innovation has the wider objective of addressing grand societal challenges, including environmental degradation, climate change, and social and economic well-being. Responsible innovation suggests links between strategic and ethical agency [

70,

71,

72] and explores approaches to companies’ innovation practices that consider responsibility, ethics, and sustainability [

73]. Previous research has explored the importance of organizational values and rituals for innovation [

43], as well as the association between different innovation strategies and organizational principles [

63,

74]. However, its integration into industry is still in its infancy, and even more so when it comes to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) [

75].

Our study demonstrates that these contradicting social and economic values can co-exist and, in fact, potentially reinforce both sets of values. Several firms found the right balance motivated as much by their cultural commitment to innovation as by market opportunity and financial growth. On the one hand, maintaining social values geared towards the local community maintains and reinforces the craft brewery’s founding purpose: to continually invent and offer interesting experiences (beer innovation), that local patrons can relate to and identify with without the appearance of external business interference. On the other hand, the simultaneous pursuit of economic values appears possible by seeking growth through the brewery’s signature products (flagship beers), expanding non-local sales and partnering with distributors and wholesalers. Interestingly, the local community seems to accept non-local businesses as long as they feel engaged and connected to the business and their beer. Accordingly, we offer the following set of propositions:

Proposition 1. Social values of responsible innovation, authenticity, and independence are pursued through a longer-term, local community focus.

Proposition 2. Economic values of growth, geographical expansion, and business partnering are pursued based on a shorter-term, non-local focus.

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

The limitations of our case-based study can serve as a basis for future research. First, our research sought to better understand how craft brewers jointly utilize economic and social values to differentiate their products from those of larger brewers. Although our research contributes to a better understanding of this area, we collected data from a set of firms in a geographically unique area. Generally, Maine is a state void of large metropolitan areas, where people have a heightened sense of connection to the environment and natural resources. Future research should seek to better understand how brewers seek to differentiate their products in alternative geographic regions and cultural norms. Second, our qualitative research approach makes it hard to quantify the degree to which CSR practices are utilized as a strategic initiative in craft breweries rather than being something that happens more by coincidence. Moreover, our findings indicate that these firms believe that balancing economic and social responsibility is an important part of their philosophical business model, but our research does not depict how this balancing act affects consumer preferences or firm success. Future research should address these quantitative questions, such as how the degree of CSR affects the brand image, consumer preference, or attractiveness as an employer within the microbrew sector. Although much of the CSR research indicates that these are all possible outcomes in large firms, there exists little research along these lines in SMEs, in particular microbreweries. Finally, we interviewed representatives from six breweries. This research approach yielded consistent and robust data from these firms, but the small sample size makes our findings hard to generalize beyond these firms. Future research should consider larger survey-based sampling methods to better understand the generalizable features of the strategic and moral use of CSR in the craft brewing industry. Similarly, consumer surveys could be a worthy avenue to better understand how a firm’s espoused social values are communicated to and received by consumers.