1. Introduction

This article responds to three concerns: transition theory’s weak engagement with agency [

1], the need for generalisable conceptual frameworks around how inter-organisational relations and place-specificity matter in transitions [

2], and contentious understandings of the sustainability concept [

3]. It does so by presenting a flexible, heuristic framework for developing place-dependent narratives of sustainability transitions grounded in investment choices. The sustainability buckets framework presented here is lodged in a strand of thought that is in the making: the ‘geography of sustainability transitions’ [

1,

2,

4,

5,

6].

(…) place-specificity matters while there is little generalisable knowledge and insight about how place-specificity matters.

This article took the above quote as a call to action. This call to action came from sustainability transitions geographers and started with the need ‘for a more intimate engagement with the dynamics of socio-technical configurations, which embodied a stronger emphasis on early formation processes’ in transitions to sustainability [

1]. This statement echoes what other transition scholars acknowledge as a weak engagement with agency in transition theory [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Approaches to fill such a gap include studies on the power relations in transitions [

9] and the geography of sustainability transitions. Hansen and Coenen (2015) developed a comprehensive review on the latter. They concluded that most geography of transitions authors still focus on mapping and making visible localised processes of change through case studies (e.g., Raven’s work in the Netherlands, India, and beyond [

5,

11]). Hansen and Coenen (2015) argue a gap remains to be filled: generalisable conceptual frameworks around how inter-organisational relations and place-specificity matter [

2]. What these and other transition authors argue could be framed as the lack of engagement with the localised, messy social dynamics that configure sustainability transitions, which we frame here as place-based ‘relational agencies’ [

12].

At stake is what can be broadly termed as the formulation of a ‘geography of sustainability transitions’ research agenda.

A recent agenda circulated among the Sustainability Transitions Research Network (STRN) aims to foster other strands of thought within the field. The agenda identifies nine research streams, including the geography of transitions, recognising a need for a greater engagement with agency via ‘co-evolution and multi-actor dynamics’ and ‘power and politics in transitions’ [

3]. The point is that transition studies require a stronger theory of social change, including frameworks and heuristic tools that can change and adapt to the realities of place-based transitions in the making. Place-dependencies include the messy social dynamics that underpin the potential for enabling, reproducing, replicating, and upscaling ongoing transitions [

13].

Köhler et al. (2019), among others, also emphasise an obstacle to filling such a gap. Researchers and scholars from different backgrounds who are interested in transitions struggle with how the notion of sustainability itself is still highly contested, partly due to the tendency in the critical literature to present generalisable approaches. ‘One-size-fits-all’ approaches may range, for instance, from

protecting the environment [

14] to supporting the development of entirely new value chains [

12], foster more sustainable

use of environmental resources [

15],

out-designing waste [

16], or addressing

social equity [

17]. The problem with these rigid approaches to defining sustainability, which we frame here as investment targets, is their inflexibility. Here we argue that while all of them might convey essential considerations, the extent of their relevance will be contingent on different people-place specificities.

Section 2 briefly elaborates on a sample of distinct approaches to sustainability that generalise the concept, which may hinder its transplantation to different people-place dynamics.

Having outlined the three concerns that inspired the creation of the sustainability buckets framework, this Introduction will now provide an overview of the theoretical underpinnings of this heuristic and how it operates. We drew upon a review of the available practice-oriented business literature (focused on strategic investment buckets) to create a flexible heuristic tool that could help navigate a universe of voices, discussing sustainability transitions from different perspectives, while focusing on the investment choices entailed.

This article starts from the stance that there is a consensus around the need to move away from unsustainable practices (or the

what); the question mark sits on the

how. Here, we direct attention to the investment needed for experimenting with different transition pathways. In the business literature, authors use the idea of

strategic buckets to conceptualise the prioritisation of resource allocation [

18,

19,

20]. Decision-makers use buckets of resources as a metaphor to guide experiments with different potential investment targets and their outcomes. The notion is helpful to transition studies because it emphasises the need to invest in sustainability outcomes, the presence of alternative configurations of resource–target relationships, and the challenges of prioritising and selecting among different targets. Regarding investment in transitions, decision makers could be placed in government, business, or any setting where investment choices are required.

The notion of strategic buckets facilitates dialogue among people from different backgrounds [

18,

19,

20]. Strategic buckets do this by connecting the people responsible for real-world deliverables (or on the ground management) with the people developing high-level strategies (or high-level management). Hutchison-Krupat and Kavadias (2015) put it this way: ‘the project manager knows the difficulty of the initiative [or chance of success translated as return on investment (ROI)], whereas senior management knows the likelihood of the initiative’s difficulty [or its articulation with an organisation’s high-level strategies] (p. 392)’. To put it bluntly, these people need to talk to each other, even though they come from different perspectives regarding strategic innovation and its implementation on the ground. This process allows for information asymmetry to reduce among different parts of an organisation, as strategic buckets are co-designed by people working both on deliverables and high-level strategists. Once a collection of strategic buckets is agreed upon, decision-makers stimulate thinking around resource allocation, entailed risk assessments, and expected ROI. Strategic buckets have proven useful for new product development and strategic innovation through dialogue facilitation and shared narratives [

18,

19,

20]. Strategic buckets constitute a praxis-oriented mechanism, for ‘decisions regarding strategic buckets and the protection of resources have little or no theoretical foundation’ [

18] (p. 908).

By bringing strategic buckets into dialogue with the geography of sustainability transitions strand of knowledge, we take an unorthodox approach to constructing new knowledge, inspired by the pathway paved by Stephenson and colleagues (2015, 2010) in the construction of a heuristic framework called sustainability cultures [

21,

22,

23]. The unorthodox design of the sustainability cultures heuristic provides a baseline to argue for the framework presented here: the sustainability buckets. Stephenson and colleagues’ heuristic is centred on understanding the ‘actor’ (transition agents broadly understood) and

why their normative orientation, material choices, and practices take shape. The sustainability buckets offer a complementary approach to that of Stephenson and colleagues’ focus on actors’ behaviours, by centring the analysis on

how investment choices may take shape to enable, upscale and transplant transitions [

13]. It also frames different sustainability approaches as distinct investment targets that can co-exist and, perhaps more importantly, that will change according to people-place specificities. This approach to building new knowledge responds to both the need for generalisable conceptual frameworks around how actor-relations and place-specificity matter in transitions and transition theory’s weak engagement with agency (which has been widely recognised in transition theory—see, for example [

9,

10,

24,

25]). It also builds a bridge with the third concern, which this article outlines as contentious understandings of the sustainability concept.

Section 2 provides an overview of sustainability as a concept grounded in distinct narratives, illustrating tensions that underpin its contentious understandings. This overview builds momentum to introduce the flexible heuristic presented here, which we designed to embody distinct sustainability narratives according to their relevance to diverse people-place dynamics.

Section 3 describes the methodological approach used to build the sustainability buckets heuristic (new knowledge construction), reflects on its successful application in a previously published study, and explores its potential for being helpful to different agri-food sectors (e.g., eggs, honey, meat, and dairy) and even distinct, high-level systems (e.g., transport or energy).

The sustainability buckets are helpful to navigate, organise, and code meanings and understandings of sustainability [

12]. In doing so, this heuristic provides a theoretical foundation for synthesising empirical data from different kinds of transition studies with the vast, rich literature on sustainability meanings and understandings. The framework proposed here can also facilitate dialogue around more sustainable investment choices and, thereby, the design of sustainability narratives that people from different backgrounds can own and share. The argument put forward here is that such shared narratives are vital for transitions to mainstream and become the new normal; however, sustainability narratives need to change according to different place-specificities and so does our flexible framework.

The purpose of the sustainability buckets is to help a nuanced design of ‘reconfiguration pathways’ [

26], in which the ‘co-evolution of levels’ could hopefully change the entire architecture of regimes [

3]. The co-evolution of levels refers to the three levels in the multi-level perspective (MLP): niche, landscape, and regime [

7,

27]. The MLP has been underpinning several studies concerned with how niche innovations may mature and challenge socio-technical regimes, leading to potential transition pathways [

26]. More open conceptions of the term sustainability would see it less as a destination and more as a process of change [

12]. As these processes are in the making, any attempt to rigidly encapsulate how meanings and values are articulated would hamper the generalisation of concepts to different contexts (that transition geographers call for). The sustainability buckets metaphor put forward in this article constitutes a useful framework to emphasise not just that there are multiple dimensions to sustainability, but that these must be materialised through investment and de-investment, and this in turn means that sustainability must be a place-dependent process of change.

This Introduction revealed the two objectives that this article meets. First, it indicated how the sustainability buckets may help synthesise the critical literature with the messy social dynamics underpinning transitions in the making, by providing a flexible heuristic to do so. Second, this Introduction presented the sustainability buckets as one step further in answering a call for more generalisable knowledge and insight about how relational agencies and place-specificity matter in transitions in the making, focusing on strategic investment choices. This Introduction also laid out the three theories that underpin the sustainability buckets: ‘sustainability cultures’ (a foundation to our unorthodox construction of new knowledge); ‘strategic investment buckets’ (our building blocks from the business literature); and ‘transition pathways’ (more specifically, our purpose: reconfiguration pathways). The following sections will unpack how the sustainability buckets meet our two objectives, by paying attention to the investment choices entailed in the mainstream penetration of sustainability transitions.

2. Sustainability Narratives

This section presents a brief literature review, highlighting different scholarly understandings of sustainability while providing a platform for elaborating on their rigid structures. It positions our proposed framework, the sustainability buckets, in the current state of knowledge on sustainability narratives. This section builds toward the sustainability buckets discussion that will follow. Importantly, this review is not meant to exhaust the vast, rich variety of narratives surrounding sustainability understandings and meanings. It is intended to provide a sample to justify how ‘sustainability is not tightly defined’ in this article but rather ‘explored in different contexts’ [

28] through the sustainability buckets framework. We will start with correlations and distinctions between weak and strong sustainability approaches and this article’s guiding transition pathway (reconfiguration), followed by the reviewed sample of sustainability narratives and the sustainability buckets’ position within these.

Solow (1974) and Hartwick (1977) argue that human capital (e.g., infrastructure and knowledge) can substitute for natural capital (e.g., fossil fuels and biodiversity) in what came to be known as the weak sustainability concept. Weak sustainability is also underpinned by the idea that ‘natural resources may decline as long as human capital increases’, and capital is left constant over generations [

29,

30]. Intergenerational equity is an economic concept of ‘fairness between generations’; based on the idea that ‘constant capital over time provides the platform for sustainable growth equity’ [

29,

30]. In the late 1980s, the weak sustainability concept began to underpin international politics. In 1992, 178 nation states signed the Agenda 21 at the Rio Summit, in which these national authorities committed to having ‘a plan for sustainable management of land resources, by no later than 1996′ [

31]. A group of scholars argue that most local authority initiatives adopted a weak version of sustainability [

32]; instead of a strong sustainability approach to planning, in which human capital and natural capital are dependent and complementary rather than interchangeable [

28]. Both weak and strong sustainability approaches require thinking through

how people can move away from less sustainable practices. In this context, transition studies frame this

how as transition pathways, e.g., [

26,

33,

34]

The interest here lies in the use of the sustainability buckets for shaping investment choices that can lead to reconfiguration pathways [

26], which aligns with the strong sustainability approach. Drawing on Geels and Schot (2007), transitioning sectors or systems would reconfigure the regime entirely (i.e., ‘reconfiguration pathway’) while less holistic interventions (related to weak sustainability approaches) will result in a ‘transformation pathway’, in which the regime adopts useable parts without changing its basic structure (also referred to as ‘greenwash’). Between these extremes, the authors highlight the potential for niche innovations to renew a regime’s technological dimension (‘technical substitution pathway’); or, due to insecurities and uncertainties leading to regime actors’ perceived loss of control, niche innovations might not mature enough to enable a technical substitution and become stuck in a ‘de-alignment’ pathway [

35].

The focus here is on the sustainability buckets as a heuristic framework for helping shape investment choices related to reconfiguration pathways. This article, however, also recognises that the notion of sustainability itself is still highly contested, and therefore understandings of reconfiguration pathways are contentious [

3]. In the remainder of this section, we use a sample of these strands of thought to illustrate tensions in the critical literature and highlight concepts pertinent to the sustainability buckets theoretical underpinnings.

Romero-Lankao et al. (2016, p. 3) argue sustainability has its ‘origins in the biology and ecology, where it refers to the rates at which renewable resources can be used or polluted without affecting ecosystem structure and function’. This minimalist framing of sustainability was taken in multiple different directions. Ecological economics focuses attention on relations ‘between human economic systems and the natural systems that support them and, thereby, demonstrate the costs associated with environmental degradation’ [

14]. Political ecology approaches, on the other hand, begin from a recognition of the politically embedded nature of economies and explore the relations between power, environmental use, the costs and benefits of those uses, and who wins and loses as a consequence [

4]. The latter approach finds an echo in the 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs).

Agyeman (2008) takes the concept further to the notion of ‘just sustainabilities’, which tends to provide strong ‘social sustainability’ to match strong ecological notions of sustainability. To him, they suggest ‘the need to ensure a better quality of life for all, now and into the future, in a just and equitable manner, whilst living within the limits of supporting ecosystems’ [

17] (p. 753). In agri-food studies, others within the political ecology tradition attempt to align the strong sustainability concept with ‘agroecological’ values [

36] or use the notion of sustainability to link ecological and social justices (ecosystems and human bodies) more directly.

Good human health requires ecological viability and, vice versa, what is good for ecology—diversity, low impact farming, sustainability—can be good for health.

The transitions to sustainability scholarship offers a systemic perspective to this kind of connection. It sees sustainability as ‘a system property’. Therefore, ‘products, services, technology or organisation cannot be sustainable on their own but may be elements of sustainable systems’ [

15] (p. 472). This observation is taken up in different ways in different applications of transitions thinking. The idea of a circular economy, for example, highlights waste and the potential to turn it into value to materialise sustainability.

Circular economy uses theory and principles from industrial ecology. The aims of industrial ecology are to close the loop of materials and substances, and reduce both resource consumption and discharges into the environment. Industrial metabolism in industrial ecology refers particularly to the idea of industrial systems working as natural ecosystems.

The point of this sample of narratives is that definitions of sustainability are ‘manifold and highly diverse’ [

38]. For example, some of these approaches could perform as destinations (e.g., circular economy and just sustainability), others as pathways (e.g., systemic transitions and transition pathways), and some as both (e.g., political ecology). From high-level notions of weak and strong sustainability to more specific approaches such as the circular economy and political ecology, what all these attempts to define and appropriate the term sustainability have in common is their boundaries that make sense in relation to specific place-dependent realities. Instead, this article welcomes the impermanence of the term sustainability. As a fluid analytical concept, sustainability offers a helpful conceptual language for performing political work in the context of social change.

3. Sustainability Buckets: Methodology for Constructing New Knowledge and Application of the Framework

Considering what is meant by sustainability represents a substantial challenge, given the breadth of understandings developed in the critical literature. To reiterate points elaborated in the Introduction, we put forward a way of thinking about these multiple perspectives grounded in investment choices and dialogue facilitation to enable, upscale, transplant, and reproduce sustainability transitions in the making (or reconfiguration pathways). This article uses the idea of strategic buckets from the business literature to emphasise the materiality of sustainability values. For commitments to be meaningful, businesses, consumers, and society at large must invest in these values. The following subsections outline the use of the sustainability buckets in building a flexible narrative for agri-food transitions, which will be synthesised with the place-based relational agencies shaping two case studies: the reorganisation of the New Zealand egg sector, cross-analysed against the case of a New Zealand mainstream honey distributor. This article extracts findings from this cross-case analysis to explain how the sustainability buckets take shape and illustrate their application as a heuristic.

The cross-case analysis of the reorganisation of the New Zealand egg sector and a mainstream honey distributor resulted from multiple interviews conducted in New Zealand and was published in 2020. Participants included farmers, business owners, distributors, and central government (for a detailed description of the methodology applied in the cross-case analysis, including number of participants interviewed and criteria for selecting participants, please see [

12]). Ribeiro (2020) used the sustainability buckets to explore how the participants prioritised investment choices [

12]. Ribeiro (2020) also ‘pattern-matched’ [

39] principles clustered in the sustainability buckets with the practices encountered on the ground, which resulted from the investment choices coded from the interviews. This was the methodological foundation for elaborating on transition pathways for the resulting products and services and their potential for aiding in the reconfiguration of sectors and systems of production, distribution, and consumption in New Zealand. This section uses the qualitative insights from this published research [

12] to demonstrate how the sustainability buckets are helpful to synthesise the critical literature with empirical findings and how they can transform according to different people-place dynamics.

This section focuses both on how the heuristic can be applied (using empirical findings from a previous study) and the methodology used to build the sustainability buckets (or construct new knowledge). Starting with the latter, the sustainability buckets transformation capacity resulted from a process to construct new knowledge understood by methodologists as a combination of abduction and retroduction [

40].

(…) abduction involves analysing data that fall outside of an initial theoretical frame or premise. Retroduction is a method of conceptualising which requires the researcher to identify the circumstances without which something (the concept) cannot exist. Used in conjunction, these forms of inference can lead to the formation of a new conceptual framework or theory.

A literature review of agri-food transitions helped outline the preliminary sustainability buckets before Ribeiro's (2020) engagement with participants (see

Table 1). As we synthesised empirical findings with the critical literature nested under our original four sustainability buckets, ‘explanatory propositions’ were revised [

42], and the evidence was examined from a new perspective in the iterative process that generated the five sustainability buckets presented in this article.

Table 1 demonstrates our starting and ending points, directing attention to how one sustainability bucket split into two (or was ‘revised’). This kind of theoretical revision grounded in empirical findings is also known as grounded theory [

43], which aided the construction of the sustainability buckets heuristic.

The following subsections will explain how each change unfolded and shaped the five sustainability buckets put forward here, which were articulated by the cross-case analysis of two New Zealand agri-food case studies. In this context, the sustainability buckets draw attention to ‘(…) economically viable edibles that promote socially just relationships while embodying circular practices, that nourish both the body and the planet’ [

12] (p. 24).

3.1. First Change: How Nourishment Was Split into Nourish the Body and Nourish the Planet

The critical agri-food literature highlights connections between nourishing the planet and the body through ideas such as agroecology. As briefly reviewed in the previous section, a group of scholars and researchers advocates for the interdependencies between human bodies and the health of soils and ecosystem services in health care and related policy making [

37]. Ribeiro's (2020) primary data collected on the reorganisation of the egg sector in New Zealand aligns with Lang (2005) and colleagues’ claims (which are grounded in agroecological values and political ecology), whereas the honey distributor shapes a different sustainability narrative.

The interviewed free-range eggs producer-distributor claims to have commissioned research to test their organic and free-range eggs against caged eggs and that this research company concluded their eggs contain three times more Omega 3, twice the amount of vitamins, are higher in natural protein and have less unsaturated fats. The participant claims the research also indicated that, nutritionally, their organic and free-range eggs are the same. The participant suggests that the keys for generating nutrient-dense eggs are the outdoor activities of the hens and their exposure to sunlight, organic grass and soil with worms. He admits that ‘everything you put into the hens’ feed will also go into the eggs’ (Eggs executive 2019, pers. comm., 27 February). These findings point to the alignment between human health and environmental stewardship put forward by Lang (2005) and colleagues.

Ribeiro (2020) investigated another food sector in New Zealand to test the nourishment principle connecting the health of the human body and the planet. The interviewee represented a honey business that claimed to sell high-quality, nutritious honey (Honey executive 2018, pers. comm., 9 November 2018). They believed the operation was sustainable because of the high-nutrient density of their honey, which they assessed in their in-house labs. They reassured their customers of such nutrient-density through the information disclosed on the packaging of their honey. This enterprise invested in technological tools for assessing the quality of their honey and claimed to consistently purchase the best quality honey from independent beekeepers, measuring pollen count in their in-house lab to make sure they were accurately advertising the type of honey (e.g., manuka, floral, etc.). The participant recognised, however, that exposing the bees to pesticides did not feature in their list of quality requirements nor did feeding the bees some of their own honey. The reason for the non-existence of pesticides in this company’s honey is the bees’ biology. Bees have the ability to filter pesticides from the nectar before turning it into honey, compromising their own health while generating high-quality honey [

44].

The honey distributor illustrates how nourishing the body might not necessarily relate to nourishing the planet. In the honey case, high-nutrient density might be achieved regardless of animal welfare or environmental stewardship. These kinds of business practices might produce transformation pathways, in which regime actors adopt parts of innovations without changing the regime’s architecture. Splitting the nourishment bucket in two can help decision-makers assess exactly where investment may be required for the reconfiguration of regimes to take place. Making a distinction between nourishing the body and the planet in strategic investment choices can help avoid greenwashing practices that might take advantage of one of the two. The following two subsections will demonstrate how the two sustainability buckets drawn from nourishment may perform, by synthesising the critical literature on meat and dairy with the empirical findings drawn from our case studies. We chose meat and dairy because these production systems raised a lot of attention in the critical literature. This approach also serves the purpose of illustrating how the sustainability buckets can transform in the analysis of distinct sectors and remain fit for purpose across distinct people-place dynamics.

3.1.1. Nourish the Body

Foods that nourish the body provide humans with essential nutrients needed for survival and healing. They boost humans’ immune systems, making people more resilient to non-communicable diseases. The rise of diet-related diseases is deeply rooted in the prevalent Western diets [

45], a contemporary concern. Diet-related diseases include different types of cancer, type II diabetes, and heart conditions, among others [

46,

47]. Healthcare costs skyrocketed worldwide due to the direct relationship between those diseases and the consumption of less nutritious foods high in fat, sugar and salt, regular alcohol intake, and meat-based diets [

45,

46,

48]. The increased human population coupled with the rise of meat consumption also contributes to rainforests loss, decreasing carbon sequestration and increasing enteric methane emissions (a pivotal contribution of ruminants to climate change) [

49]. In other words, the rise of meat consumption makes both people and the planet sick.

Some nutritionists advise humans to eat a balanced plant-based diet, which provides important micro-nutrients, including omega 3s, vitamins, and proteins [

45,

50,

51]. For example, some nutritionists advise people to decrease their meat consumption, eat one egg per day, and honey instead of sugar, to complement a balanced plant-based diet [

45]. However, there is no consensus in the literature that a completely vegan diet can adequately nourish the human body. What the literature highlights is the multiple health benefits of decreasing meat consumption worldwide while increasing the variety of ingredients in plant-based diets. While meat can be a valuable source of zinc, iron, and vitamin B12, the UN, the FAO, and others recommend an intake of no more than 500 g of cooked meat per week—with a small portion of the 500 g potentially comprised of processed meats, such as free-range ham [

45,

52]. The World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) links ‘eating more than 500 g of cooked red meat each week’ with ‘a higher risk of colorectal cancer’ [

52].

3.1.2. Nourish the Planet

Here we argue that animal welfare could potentially be framed as nourishing the body but also directs attention to non-human bodies, sustainable animal husbandry, and what might be termed nourishing the planet. Nourishing the planet in this way can further boost systemic syntropy or regenerative production systems [

53], for example, through production practices grounded in agroforestry [

54], agroecology [

36], permaculture [

55], and food forestry [

56]. In a regenerative production system, bees, for instance, not only produce nutritious honey but also perform an important ecosystem service as pollinator insects. Furthermore, regarding the eggs case study, although this article frames eggs as vital elements in nourishing the human body (see

Section 3.1), it also recognises how laying hens’ manure can become a natural fertiliser (nourishing the planet).

Animal husbandry can further boost the nutrients circulating in agri-food systems [

16]. Grazing cattle might perform a valuable ecosystem service if rotated to different pastures according to seasonality and grass growth, to promote soil carbon sequestration. By embedding other approaches, such as agroforestry and permaculture, regenerative agriculture results in plural outputs such as biomass, nutrient-dense foods, and non-edible plants while providing a platform for sustaining biodiversity [

54]. For example, the eggs case study presents links between this kind of animal husbandry and agroecological systems of food production in New Zealand. According to the egg participant, their free-range laying hens find the grass at the height appropriate for finding organic worms because the farmers rotate grazing animals. They use sheep when the grass is too tall and sell the manure to external partners. In this context, biodiversity coupled with strategic commercial partnerships constitute keys to unlock more sustainable food futures.

3.2. Second Change: From Fairtrade to Socially Just Relationships

The socially just relationships sustainability bucket constitutes the second change drawn from the synthesis of the critical literature with the empirical findings. The starting point of this sustainability bucket’s literature review was Fairtrade and how this labelling scheme would benefit farmers. Fairtrade was the starting point because of its declared focus on the farmers’ livelihood and wellbeing: ‘(…) empower millions of farmers and workers around the world by tackling poverty and poor working conditions (…)’ (

https://fairtradeanz.org/what-is-fairtrade, accessed on 9 August 2021). According to the Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International, Fairtrade labels operate on two dimensions. The contracts signed with farmer-suppliers establish a minimum price, even if conventional commodity prices fall. In addition, a premium price is paid ‘to allow farmers to cover their cost of production and improve their lives–by, for instance, providing money to be invested in their farms and in schools’ (

https://info.Fairtrade.net, accessed on 9 August 2021). However, private certification companies provide expensive labelling schemes that can make the Fairtrade label too costly for the farmers/producers this label is meant to protect [

57]. This sustainability bucket argues that socially just relationships can be established regardless of labelling schemes and may embody other kinds of Fairtrade principles, such as commitments to buy the farmers’ produce before the harvesting season and, therefore, without precise information about the yield (e.g., community supported agriculture [

58]).

Socially Just Relationships

The empirical findings on the upstream supplier of free-range and organic eggs helped articulate the socially just sustainability bucket. The business consists of over 20 individually owned farms, whose eggs are labelled under one brand. The business model resembles that of a cooperative. The farmers get to keep ownership of the land and sign contracts guaranteeing a price fluctuation of their eggs of no more than 3% above or below current values. Without using the Fairtrade labelling scheme, which would incur further costs, this business is mainstreaming their free-range eggs nationally and abroad without compromising the livelihood of the farmers. On the other hand, the honey business buys the best possible quality honey from independent beekeepers for the lowest possible price. Thus, socially just commitments appear to be absent from their business strategy in favour of achieving a higher ROI.

The synthesis of the critical literature with the empirical findings led to framing socially just relationships on the grounds of transparency and equity, regardless of Fairtrade labelling schemes. Socially just relationships embody an understanding of how equitable and transparent the negotiations between economic actors from different parts of the value chain are. These require investment and thus again imply a socially just relationships sustainability bucket. Often, it is in this sphere of investment choices that producers, processors, and distributors fail to grasp the full intent of sustainability transitions—let alone materialise them into just transitions [

59]. Groups of people who create and negotiate products and services routinely may fail to account for this dimension of sustainability while mainstream economic actors blind themselves to it in the pursuit of profit and higher ROI [

60,

61]. While contemporary economies are primarily shaped by uneven power relationships and the practices of corporate capitalism, this sustainability bucket draws attention to the wellbeing and livelihood of the people who produce our foods.

3.3. Changed the Least: Circular Economy and Economic Viability

The circular economy and the economic viability sustainability buckets changed the least during the synthesis of the empirical insights with the review of the agri-food critical literature. Brief literature reviews are clustered in the following subsections, configuring the two sustainability buckets on a high level. We chose to ground these two sustainability buckets on high-level theories to demonstrate how the sustainability buckets framework transforms to suit not only different agri-food sectors but also high-level, distinct systems. Although the literature comes from agri-food studies due to the case studies used in this article, the high-level framing of circular economy and economic viability proposed here demonstrates how the sustainability buckets could help organise investment choices targeting other systemic transitions, such as transport or energy. We also use the economic viability sustainability bucket to highlight articulations between the five sustainability buckets, by going back to the critical literature on meat and dairy to elaborate on notions of perceived value and external costs.

3.3.1. Circular Economy

The circular economy approach aims to address the environmental impacts of linear practices or the ‘take-make-dispose’ mindset embodied in ‘business as usual’ [

62]. Food waste is a significant concern worldwide. People currently waste around 33% of the food we produce or 1.3 billion tonnes per year [

63]. The UN predicts if food waste was cut by only 25% [

64], that would be enough to feed the entire human population, which reached 7.7 billion in 2019. Drawing upon both Steel (2013) and the FAO (2011), if 25% of wasted food could feed 1 billion people in the early 2010s, enough food was already produced to feed around 10 billion people back then. And yet Steel estimates that one billion of us were obese while another billion starved in 2013 [

65]. Households account for around 40% of the total food wasted in parts of the Global North, whereas food loss happens mostly during production and distribution in parts of the Global South [

66]. A food circular economy nourishes the planet by avoiding waste and carbon emissions in production, distribution, and consumption practices [

16]. In a food circular economy, the consumer transitions into an active agent that purchases sustainable foods, re-directs packaging for recycling, avoids food waste in the household, and practises composting [

66,

67], which is no small challenge.

Both the egg and honey participants seem to lack knowledge on how households performed in the waste generation from egg and honey by-products. They did, however, explore articulations between ROI and circular practices. The honey business uses plastic jars. The participant claimed that plastic is a business strategy to decrease the logistical costs of selling overseas. The eggs participant utilises recyclable cardboard boxes and engages more directly with circular practices by selling the hens to backyard farmers right after egg production declines (instead of killing the laying hens). All 22 farmers operate the same way to avoid the hens’ premature death while retaining some gross profit over their sale. For the eggs participant, when egg production goes below a certain level, they would either kill or sell the hens. The feed and land availability costs become too high to sustain the necessary ROI and positive cash flow. The egg participant’s circular endeavours are embedded in the broader perspective of the circular economy, which directs attention to the value generation potential of avoiding waste and the issues of food access inequality the following subsection will touch on. The point is that circular practices can increase ROI for businesses (e.g., profit from selling less productive laying hens, instead of the costs of killing them) and diminish issues to do with access inequality on the other end of value chains (e.g., the potential for feeding the hungry by redirecting food waste to those in need).

3.3.2. Economic Viability

The economic viability sustainability bucket is of particular interest to the heuristic presented here, as it implies investment that may shape the mainstream penetration of sustainability transitions. Economic viability involves securing the returns needed to sustain ethical commitments embedded in the other sustainability buckets, such as circular and socially just practices, which also directs attention to the trade-offs and investment choices that currently characterise mainstream food provisioning (or the agri-food regime) in New Zealand. For instance, we discussed circular trade-offs (profits of selling less productive laying hens versus the costs of killing them) and socially just relationships (eggs cooperative model versus honey quality for the lowest possible price). Another example of relevant trade-offs refers to how sustainable foods have been portrayed by some Western media as too costly due to perceived inefficiencies in sustainable production systems, such as the amount of land required [

68]. The egg participant claims to have been accused of inefficiency, for the free-range hens’ lifestyle would require five times more land than caged eggs production systems (including ‘barn raised’ and ‘aviary’ systems of production). At the same time, the honey participant claimed to avoid purchasing from organic beekeepers, who protect the bees from pesticides and feed them some of their honey, due to the increase in costs that would impact their prices for end consumers. The point is how these externalities and production practices impact the economic viability to the end consumer. Sustainable foods, critics argue, may fail to feed everyone sustainably and remain a niche production system to feed the few who can (or will) pay such premium prices.

Industrialised production systems, critics argue, are more cost-effective and therefore more suitable to feed a growing human population. For example, one could argue beef has never been cheaper, and a growing number of people nowadays get to enjoy what was once perceived as a luxury. As is the case with other foods, industrialised animal husbandry democratised access to beef, while organic meat remains an expensive niche product that would require too much land to produce. Yet the critical literature highlights how the real cost of cheap food gets externalised and paid for in other ways, without necessarily enhancing the life quality of farmers (

socially just relationships) [

14,

36,

37,

46,

69]. Cheap beef consumes resources and contributes to both climate change (

circular economy) and the costs of health care systems skyrocketing worldwide (

nourish the body) [

49,

69,

70]. The nourish the body sustainability bucket highlighted links between excessive meat consumption and diet-related diseases, but beef can also mal-nourish the planet (

nourish the planet). According to the FAO, cattle are the animal species responsible for the most emissions from agriculture, ‘representing about 65% of the livestock sector’s emissions’ worldwide. Grazing animals also put pressure on land use. The FAO estimates that 26% of the world’s ice-free land is used for livestock grazing (e.g., cows and sheep) and that 33% of croplands are used for livestock feed production [

71].

To illustrate the external costs of industrialised food systems, Patel (2012) famously estimated the cost of a Big Mac hamburger at around USD 200 predominantly due to the externalities embedded in intensifying grazing cattle (or economies of scale) [

70]. Economies of scale, or achieving proportionate savings in cost through an increased level of production [

72], directs attention to how efficiency underpins economic viability. Some authors, however, claim that sustainable practices get lost within economies of scale (e.g., [

73] on organics mainstream penetration in California). Others argue that any food transition to sustainability will have to involve mainstream penetration and, consequently, regime actors (i.e., supermarkets, catering services, and other major retailers) (e.g., [

74] on consumption junctions). The sustainability buckets framework aligns with the latter approach. Grounded in the empirical findings, the underlying assumption explored in the economic viability sustainability bucket is that economies of scale may be a vital component of sustainability transitions while recognising diverse pathways may also be produced. The honey distributor achieved volume sales domestically and abroad by stripping down the honey bought from New Zealand beekeepers to a minimalist for profits approach, even though they invest in the nourish the body sustainability bucket (using technology to classify the quality and kind of honey commercialised under their brand). The eggs participant, on the other hand, invests resources in all the sustainability buckets presented here, demonstrating how the use of technology to upscale free range and organic eggs production in over 20 individually owned farms may enable the mainstream penetration of sustainability transitions.

4. Discussion

The sustainability buckets outlined in the previous section provided an understanding of how this heuristic tool can be useful to synthesise the critical literature with empirical findings. In doing so, this article meets the first objective outlined in the Introduction. The second objective met regards how the sustainability buckets constitute one step further in answering a call by transition geographers. They called for more generalisable knowledge and insight about how relational agencies and place-specificity matter in transitions in the making, which the sustainability buckets achieve through a focus on strategic investment choices and the heuristic’s capacity to transform, remaining fit-for-purpose across distinct people-place dynamics.

Section 3 demonstrates how the sustainability buckets can be used as practice-oriented generalisable knowledge by applying the framework to different sectors (meat and dairy). Distinct place-dependent realities were explored using the eggs and honey New Zealand case studies. The heuristic’s applicability to these different sectors and place-dependent realities highlights the sustainability buckets capacity to change and adapt to the people-place dynamics relevant to distinct sectors and, the evidence from a previous publication suggests [

12], potentially even other high-level systems (e.g., transport or energy).

The sustainability buckets are a tool for exploring pathways for changing the system from within, in which case, ROI remains a vital component of sustainable investment choices. One of our case studies demonstrates how ROI and externalities do not necessarily imply BAU. The New Zealand free-range eggs case achieves ROI and economic viability grounded on socially just relationships, circular practices, and nourishing both the body and the planet (see argument for splitting the nourishment bucket in

Section 3.1). The sustainability buckets can also help flag attempts to greenwash unsustainable practices that could be framed as sustainable on one of the dimensions broken down by the sustainability buckets. As the honey case study demonstrates, nourishing the body and economic viability may not suffice if socially just relationships, circular practices, and nourishing the planet are overlooked (see articulations of all sustainability buckets in

Section 3.3.2).

The Introduction, however, also highlighted that the sustainability buckets might facilitate dialogue, enabling the construction of sustainability narratives that people from different backgrounds can own and share, which is the focus of this discussion. An example of communication enhancement is how the heuristic structured the design of the interviews, which were informed by the literature reviewed before engagement with participants (see

Table 1). The questions targeted resource allocation to sustain practices such as more land for the laying hens’ free-range lifestyle, the increase of technological capability to assess honey quality, and the strategic development of one of the most successful national branding strategies in the world: NZ Inc. [

75,

76]. The government announcement to phase out caged eggs in the country was issued under the Animal Welfare Act, one of the legislative levers of NZ Inc. [

77]. According to a government interviewee, the act aimed at increasing the value of exports from the country’s primary sector (Central government participant 2018, pers. comm., 13 September). This strategy spilt over domestically, influencing the reorganisation of the egg sector in New Zealand. The eggs participant acknowledges that government’s announcement helped their free-range and organic eggs to mainstream, as supermarkets followed government’s lead and issued a similar announcement shortly afterwards. Government’s announcement could be framed as landscape dynamics that opened windows of opportunity for the co-evolution of the reorganisation of regime actors (supermarkets’ announcement) and technical substitution (free-range eggs upscaling production to meet a rising domestic demand).

Regarding the dialogue facilitation component of the heuristic, people working in business and government participated in the published research from which this article draws empirical insights [

12]. Both clusters of relational agencies (business and government) share one concern: the justification of resource allocation. Businesspeople need to account for their decisions by articulating investment choices with the strategies set out for the enterprise and the increase of revenue target. Governments, on the other hand, need to justify the expenditure of taxpayer money. However, in the reorganisation of the egg sector in New Zealand, there is another component at play. Government’s and supermarket’s announcements to phase out caged eggs could be framed as landscape dynamics that opened windows of opportunity for the mainstream penetration of free-range eggs in the country and the related mobilisation of resources to upscale this system of production (see [

78]). This transition could be framed as a technological substitution pathway, for a reconfiguration pathway would depend on the distributors’ capacity to achieve a higher degree of sustainability. Future studies could help unpack how sustainable major retailers’ business models could become. There is a need for more information and insights into how these mainstream actors operate.

The dialogue facilitation component articulates clusters of people sitting in different parts of the value chain, which draws attention to the articulations between the sustainability buckets themselves (as signalled in the economic viability sustainability bucket, in

Section 3.3.2).

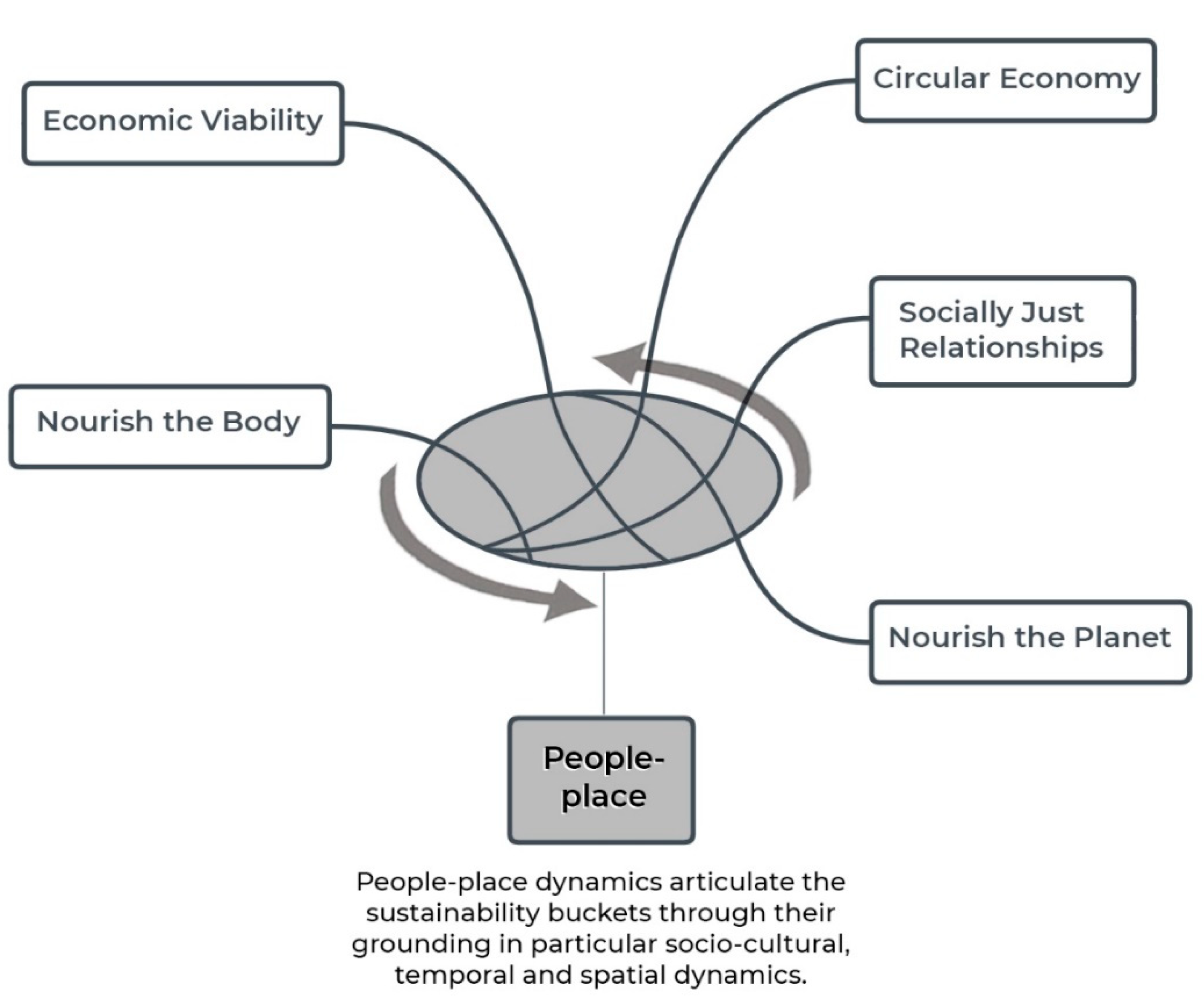

Figure 1 illustrates these relationships. It represents the five sustainability buckets that took shape in their articulation with the analysed case studies, as a conceptual tree seen from above that finds its roots in people and place. People-place dynamics, represented at the centre of

Figure 1, is where time, regulations, non-bio and bio-materials, and energy flow and transform. People-place dynamics is where the sustainability buckets heuristic tool comes together to forge new articulations of realities and, consequently, re-shape the sustainability buckets themselves. The use of double arrows and the notion of space, rather than the singular arrows of fixed logics and the boxes of stable entities, highlights relationality, recursivity, and co-constitutiveness rather than cause and effect. The double arrows symbolize movement and how the sustainability buckets take new shapes and become re-arranged through negotiations of resource allocation. The people-place articulation provides a grounding property to the investment choices embodied in transitions in the making, which extrapolates spatial embeddedness beyond the food dimension.

5. Conclusions

What inspired the creation of the sustainability buckets was an interest in how we could move on from discussing the weaknesses of different sustainability-related strands of knowledge into a constructive dialogue that could help upscale, reproduce, or transplant transitions to sustainability in the making. In doing so, this article achieves two objectives. First, it presents an innovative heuristic framework that can adapt to the place-specificities of different transitions in the making. Our framework directs attention to the need for strategically investing in transitions while facilitating dialogue among strategic and on-the-ground decision-makers involved in processes of resource allocation. Another publication tested these considerations, by interviewing business and government people (among others) and organising insights around investment choices (or sustainability buckets) [

12]. Decision-makers, however, could be placed in any setting where investment choices are required (e.g., NGOs).

Section 2 and

Section 3 reviewed some vital sustainability concerns, suggesting that different sustainability investment targets will embody different resource allocation considerations. We argue such targets are contingent not only on investment choices but also people-place dynamics.

In the case of the reorganisation of the egg sector in New Zealand, parts of the critical literature directly related to what was found on the ground, whereas others provided the opportunity to expand the horizons of concepts and ideas. The point is sustainability narratives need to be tested against real-world transitions. For instance, there is a vital articulation to highlight between transition theory and how the cross-case analysis of the data collected on free-range eggs and honey made in New Zealand led to revise ‘explanatory propositions’ [

42] from the critical literature. Most notably, we examined some of the connections between nourishing the planet and the body from a new perspective, by splitting the nourishment sustainability bucket in two. The analysis of the honey case study sheds light in this regard, by demonstrating how nutrient-dense honey may lack a correlation with nourishing the bees (or the planet). Bees’ capacity to filter pesticides and endure a sugar diet produced opportunities for transformation pathways in the honey case study. In other words, it is possible to greenwash the, nevertheless, high-nutrient dense honey produced. Splitting the nourishment sustainability bucket into two aids the design of reconfiguration pathways, which requires recognising where nourishment connections may be real and where they could produce opportunities for transformation pathways (or greenwash).

Second, every time they are transplanted and re-shaped, the sustainability buckets framework may help facilitate the co-design of a plurality of sustainability transitions narratives that people from different cultural backgrounds could own and share. As we talked with government and businesspeople in New Zealand, we used the notions nested under the sustainability buckets to understand how investment choices were underpinning potential reconfiguration pathways in the egg sector and what could be framed as transformation pathways found in a New Zealand honey case study. People from different backgrounds could relate to this notion, which enabled us to build a narrative structured by the five sustainability buckets. The synthesis of such empirical insights with the critical literature reviewed shaped the five sustainability buckets, which may change and incorporate new notions of sustainability relevant to dynamics embodied in distinct place, people, and time. The evidence suggests that, as they change, these five sustainability buckets may help shape resource allocation for transitions not only agri-food-related but also other high-level systems, such as transport or energy.

This article draws on the findings from a published study to present a new heuristic that meets two objectives. To reiterate, we first discussed how the sustainability buckets may help synthesise the critical literature with the messy social dynamics underpinning transitions in the making, by providing a flexible heuristic to do so. Second, the sustainability buckets contribute to answering a call for more generalisable knowledge and insight about how relational agencies and place-specificity matter in transitions in the making, focusing on strategic investment choices. And

Section 4 elaborated on how the dialogue facilitation feature of the heuristic underpins the two objectives met by this article. The three points we put forward in this article shape the sustainability buckets as a conceptual contribution to the geography of sustainability transitions. This article’s rationale started from the position that sustainability transitions are place-dependent and in the making. The five sustainability buckets presented here, therefore, constitute a snapshot in a specific place and time. We designed the sustainability buckets by embracing the impermanence of processes in the making, or transitions, so that this heuristic framework could change, remain fit for purpose, and helpful as hopeful transformations evolve.

A gap remains, however, that could be framed as a third, aspirational objective that lurked in the shadows of this article. There is still the need for testing the framework in the early stages of decision-making processes and, therefore, the construction of shared sustainability narratives. Perhaps the most exciting thing about our framework is that it can help people enable actual transitions, their transplantation, and reproduction potentials. Decision maker(s) may use the sustainability buckets alongside other investment priorities (or strategic buckets) to allocate resources to actions that, ideally, generate both return on investment (ROI) and more sustainable outcomes. Decision makers, transition researchers, and sustainability activists would also create their own sustainability buckets, depending on the people-place dynamics where they are embedded. As the framework takes new shapes, it will remain fit-for-purpose and aid a plurality of decision makers to think through investment choices relevant to creating more sustainable, place-based futures.