Learning Football for Good: The Development and Evaluation of the Football3 MOOC

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background of Football3 and Football3 for All

3. Development of the MOOC

3.1. Analysis

3.2. Design

3.3. Development

3.4. Implementation

3.5. Evaluation

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Framework and Design

4.2. Data Collection

4.2.1. Feedback Survey

4.2.2. Focus Group Discussions

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results

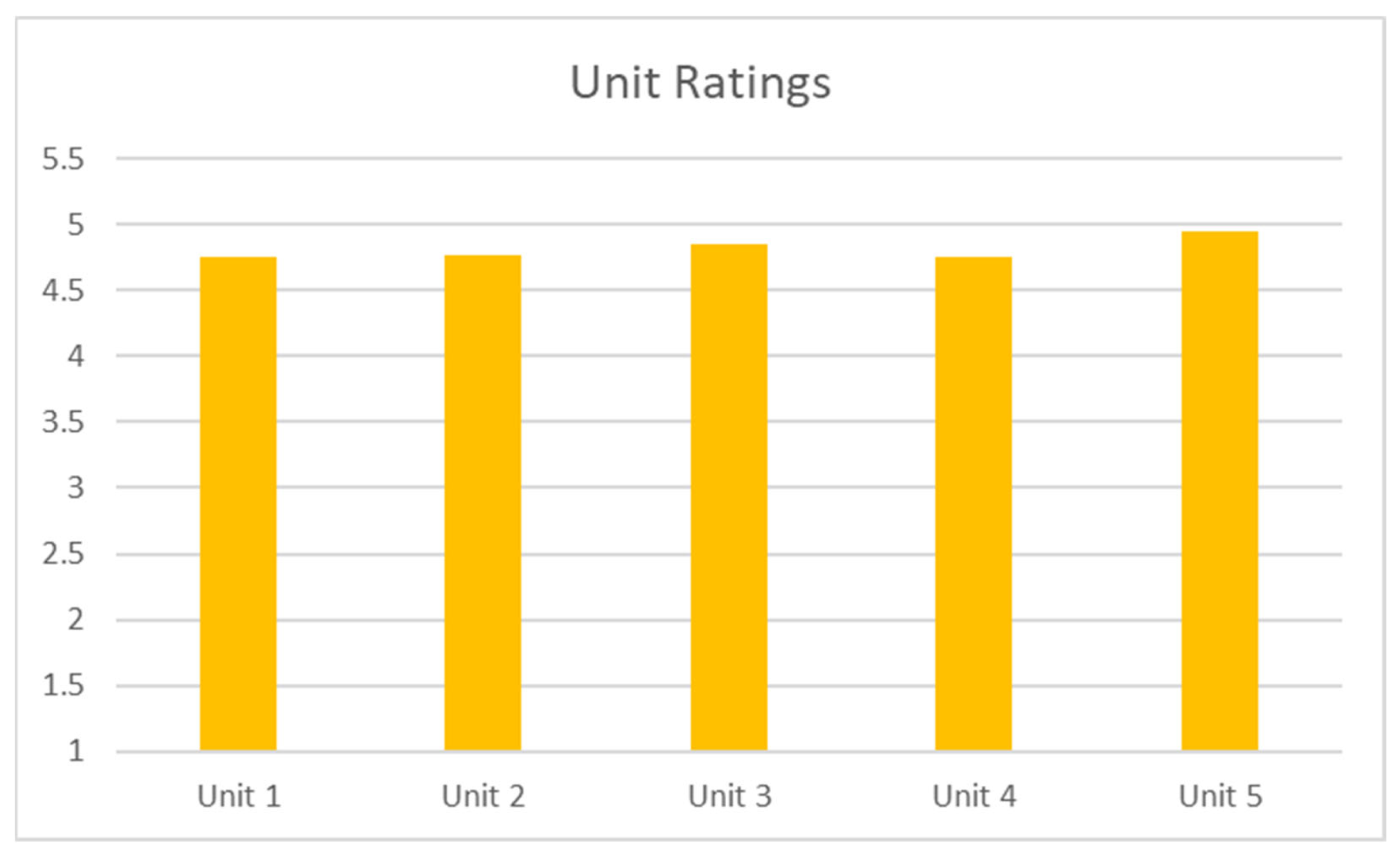

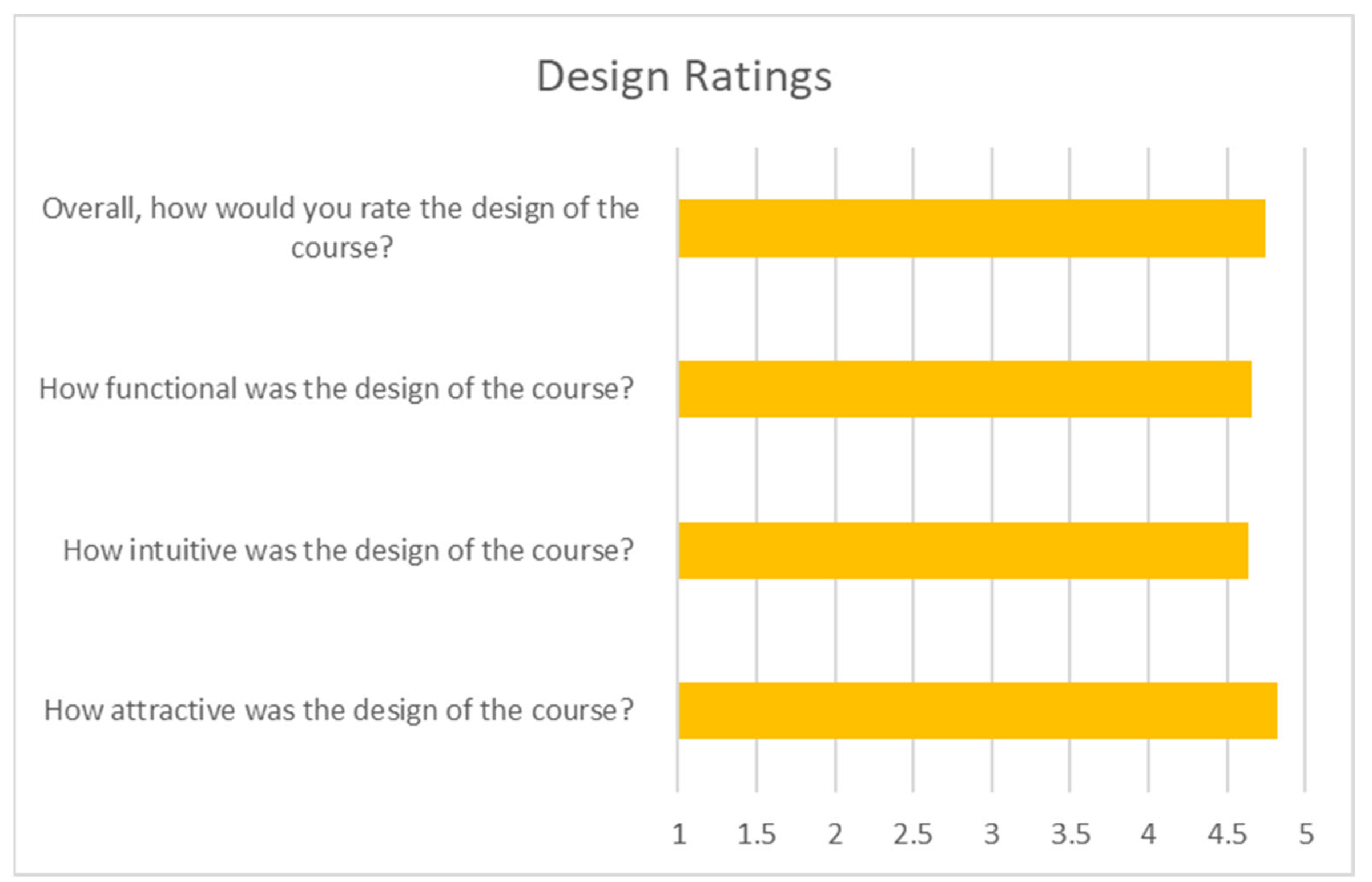

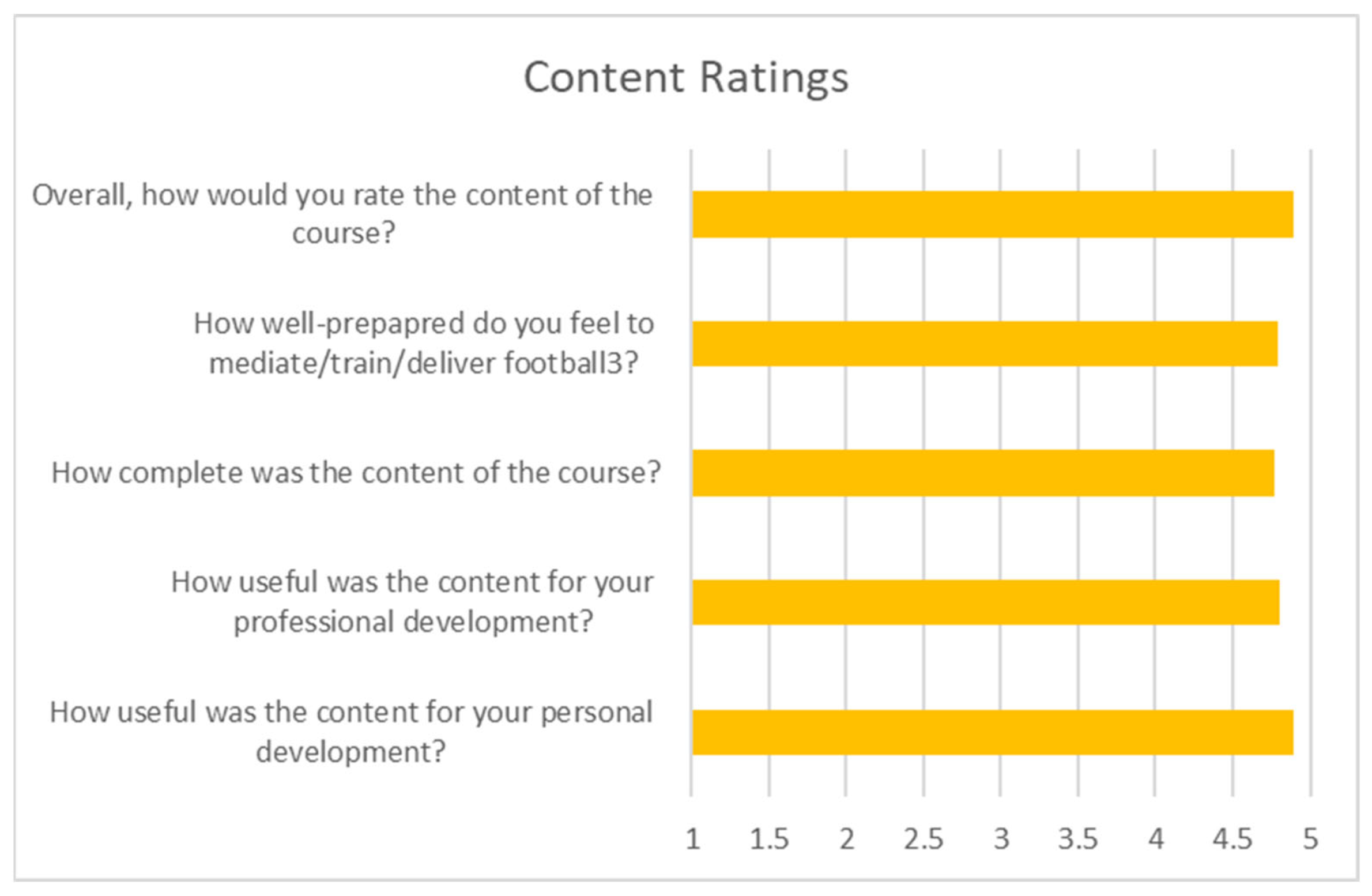

5.1. Quantitative Results Course Satisfaction

5.2. Qualitative Results

5.2.1. Course Satisfaction

5.2.2. Readiness and Transfer to the Pitch

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Eekeren, F.; Ter Horst, K.; Fictorie, D. Sport for Development: The Potential Values and Next Steps. Review of Policy, Programs and Academic Research 1998–2013; International Sports Aliance: ‘s-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beutler, I. Sport serving development and peace: Achieving the goals of the United Nations through sport. Sport Soc. 2008, 11, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coalter, F.; Theeboom, M.; Truyens, J. Developing a programme theory for sport and employability programmes for NEETs. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2020, 12, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansell, A.H.; Giacobbi, P.R.; Voelker, D.K. A Scoping Review of Sport-Based Health Promotion Interventions With Youth in Africa. Health Promot. Pract. 2021, 22, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, F.; Jones, A.; Smith, L. Building Peace through Sports Projects: A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, A. Peace Building Through Sport? An Introduction to Sport for Development and Peace. J. Confl. 2013, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, L. Can sport for development programs improve educational outcomes? A rapid evidence assessment. Phys. Cult. Sport. Stud. Res. 2020, 87, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, P.G.; Woods, H. A systematic overview of sport for development and peace organisations. J. Sport Dev. 2017, 5, 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenkorf, N. Sustainable community development through sport and events: A conceptual framework for Sport-for-Development projects. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Camiré, M. Reconciling competition and positive youth development in sport. Staps 2015, 3, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Llerena, A.; Pedrero, M.N.; Flores-Aguilar, G.; López-Meneses, E. Design of a Methodological Intervention for Developing Respect, Inclusion and Equality in Physical Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K.; Schröder, R.; Minas, M. Streetsport-for-Development: Ansätze und Potenzial von Streetsport im Entwicklungskontext. In Sport im Kontext von Internationaler Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung: Perspektiven und Herausforderungen im Spannungsfeld von Wissenschaft, Politik und Praxis; Petry, K., Ed.; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen, Germany, 2020; pp. 193–206. ISBN 9783847423720. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, J.C.; Barreira, D.; Galatti, L.; Chow, J.Y.; Garganta, J.; Scaglia, A.J. Enhancing learning in the context of Street football: A case for Nonlinear Pedagogy. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2019, 24, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, L.; Hebel, M.; Meijers, B.; Springborg, G. Football3 Handbook: How to Use Football for Social Change; streetfootballworld: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Streetfootballworld. Annual Report 2016; Streetfootballworld: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C. Can “Participatory Football” Foster Social Inclusion of Marginalized Youth? Hertie School of Governance: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas, L.; Springborg, G. Football3 Trainer Manual; streetfootballworld: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gannett, K.; Kaufmann, Z.; Clark., M.; McGarvey, S. Football with three ‘halves’: A qualitative exploratory study of the football3 model at the Football for Hope Festival 2010. J. Sport Dev. 2014, 2, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Strachan, L.; MacDonald, D.J.; Côté, J. Project SCORE! Coaches’ perceptions of an online tool to promote positive youth development in sport. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2016, 11, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McSweeney, M.; Millington, R.; Hayhurst, L.M.; Darnell, S. Becoming an Occupation? A Research Agenda Into the Professionalization of the Sport for Development and Peace Sector. J. Sport Manag. 2021, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, B.; Phillips, J.; Vanreusel, B. Opportunities and challenges facing NGOs using sport as a vehicle for development in post-apartheid South Africa. Sport Educ. Soc. 2014, 19, 789–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jansen, D.; Schuwer, R. Institutional MOOC Strategies in Europe; EADTU: Heerlen, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Del Sánchez-Vera, M.M.; Prendes-Espinosa, M.P. Beyond objective testing and peer assessment: Alternative ways of assessment in MOOCs. RUSC. Univ. Know. Soc. 2014, 12, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The International Platform on Sport and Development. Sport for Sustainable Development: Designing Effective Policies and Programmes. Available online: https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/sport-for-sustainable-development (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Sector Programme Sport for Development. Learning Lab. Available online: https://www.sport-for-development.com/learning-lab (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Iuliano, E.; Mazzilli, M.; Zambelli, S.; Macaluso, F.; Raviolo, P.; Picerno, P. Satisfaction Levels of Sport Sciences University Students in Online Workshops for Substituting Practice-Oriented Activities during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, L.; Robrade, D. The Challenges and Realities of E-Learning During Covid-19: The Case of University Sport and Physical Education. Challenges 2022. in review. [Google Scholar]

- Armour, K.M.; Casey, A.; Goodyear, V.A. Armour, K.M.; Casey, A.; Goodyear, V.A. A Pedagogical Cases Approach to Understanding Digital Technologies and Learning in Physical Education. In Digital Technologies and Learning in Physical Education: Pedagogical Cases; Casey, A., Goodyear, V.A., Armour, K.M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781315670164. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. E-Learning Methodologies and Good Practices; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011; ISBN 9789251344019. [Google Scholar]

- Branch, R.M. Instructional Design: The ADDIE Approach; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; ISBN 9780387095059. [Google Scholar]

- West, C.; Griesbeck, J. Die andere Dimension des Spiels: Streetfootballworld festival 06–zur Rekonstruktion der Verknüpfung von Gewalt, Verwundbarkeit und Identität über Erinnerung, Gedächtnis, Kommunikation und Raum. In Organisation und Folgewirkung von Großveranstaltungen; Bogusch, S., Spellerberg, A., Topp, H.H., West, C., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009; pp. 191–225. ISBN 9783531161969. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Football3 for Respect! Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/579748-EPP-1-2016-2-DE-SPO-SCP (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Biester, S.; Rees, C. Fußball-Lernen-Global: Wie Organisationen weltweit über Straßenfußball gemeinsam zu sozialem Wandel beitragen. In Sport im Kontext von Internationaler Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung: Perspektiven und Herausforderungen im Spannungsfeld von Wissenschaft, Politik und Praxis; Petry, K., Ed.; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen, Germany, 2020; pp. 181–192. ISBN 978-3-8474-2372-0. [Google Scholar]

- Segura Millan Trejo, F.; Norman, M.; Jaccoud, C. Encounters on the Field: Observations of the Football-3-Halves Festival at the Euro Cup 2016. Sociol. Sport J. 2018, 35, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- streetfootballworld. Welcome to the Football3 Mobile Course. Available online: football3.nimbl.uk/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Crawford-Ferre, H.G.; Wiest, L.R. Effective Online Instruction in Higher Education. Q. Rev. Distance Educ. 2012, 13, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Picciano, A.G. Theories and Frameworks for Online Education: Seeking an Integrated Model. OLJ 2017, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, A.; Chen, X. Online Education and Its Effective Practice: A Research Review. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2016, 15, 157–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azevedo, J.; Marques, M.M. MOOC Success Factors: Proposal of an Analysis Framework. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Innov. Pract. 2017, 16, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- University of Vienna. EDU:PACT Module Review and Validation Report; University of Vienna: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thiel, A.; Diehl, K.; Giel, K.E.; Schnell, A.; Schubring, A.M.; Mayer, J.; Zipfel, S.; Schneider, S. The German Young Olympic Athletes’ Lifestyle and Health Management Study (GOAL Study): Design of a mixed-method study. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matsangos, N.; Gargalianos, D.; Coppola, S.; Vastola, R.; Petromilli, A. Investigation of skills acquired by athletes during their sporting career. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2020, 15, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Furim Institut. Athletes Becoming Social Entrepreneurs! Developing a Gamification Based Social Entrepreneurship Training Program for Athletes: Pilot Scheme Report; Furim Institut: Oslo, Norway, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Joffe, H. Thematic Analysis. In Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health and Psychotherapy; Harper, D., Thompson, A.R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, UK, 2011; pp. 209–223. ISBN 9781119973249. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; ISBN 9780199588053. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 160940691773384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- streetfootballworld. Football3 for All. Available online: https://www.streetfootballworld.org/project/football3-all (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Svensson, P.G.; Hambrick, M.E. Exploring how external stakeholders shape social innovation in sport for development and peace. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonia, T.G.; Pierpaolo, L. Research on a massive open online course (MOOC): A Rapid Evidence Assessment of online courses in physical education and sport. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2019, 19, 2328–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-A.; Wu, D.; Cheng, J.-N.; Fu, B.; Zhang, L.; Lu, A.-M. Application of MOOC Teaching in Sports Course Teaching Practice. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. 2017, 13, 8089–8097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponticorvo, M.; Schembri, M.; Miglino, O. How to Improve Spatial and Numerical Cognition with a Game-Based and Technology-Enhanced Learning Approach. In Understanding the Brain Function and Emotions; Ferrández Vicente, J.M., Álvarez-Sánchez, J.R., de La Paz López, F., Toledo Moreo, J., Adeli, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, India, 2019; pp. 32–41. ISBN 9783030195908. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, M.A.; Farrell, K.; Wolff, E.A.; Hillyer, S.J. Sport for development and peace: Surveying actors in the field. J. Sport Dev. 2019, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Analysis | Needs and target group analysis to identify the suitability of e-learning as a mode of delivery and the key characteristics of the target group. |

| Design | This includes formulating the learning objectives, determining the order in which objectives should be achieved and selecting instructional/delivery strategies. In the end, this step leads to a blueprint that will be used as a reference to develop the course. |

| Development | In this stage, e-learning content is produced (e.g., videos, quizzes, graphics, etc.). |

| Implementation | The course is installed and delivered to learners. |

| Evaluation | Evaluation is a continuous process that touches all steps. This can include evaluating learner reactions, learner skill development or the impact on organisations. |

| Unit | Learning Contents |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Code | Country | Gender | Background |

|---|---|---|---|

| FGD1 | Brazil | F | Local, sport-based NGO |

| FGD2 | Canada | F | Local, sport-based NGO |

| FGD3 | Canada | F | Local, sport-based NGO |

| FGD4 | Kenya | M | Local, sport-based NGO |

| FGD5 | Kenya | M | Local, sport-based NGO |

| FGD6 | Spain | M | Local, sport-based NGO |

| FGD7 | Ukraine | M | Local, sport-based NGO |

| FGD8 | Germany | M | International development organisation |

| FGD9 | Kenya | F | Local, sport-based NGO |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moustakas, L.; Kalina, L. Learning Football for Good: The Development and Evaluation of the Football3 MOOC. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2061. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042061

Moustakas L, Kalina L. Learning Football for Good: The Development and Evaluation of the Football3 MOOC. Sustainability. 2022; 14(4):2061. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042061

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoustakas, Louis, and Lisa Kalina. 2022. "Learning Football for Good: The Development and Evaluation of the Football3 MOOC" Sustainability 14, no. 4: 2061. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042061

APA StyleMoustakas, L., & Kalina, L. (2022). Learning Football for Good: The Development and Evaluation of the Football3 MOOC. Sustainability, 14(4), 2061. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042061