Abstract

Lubenice on the island of Cres in Croatia is one of the most valuable examples of a small historic Mediterranean town. Although the settlement is protected as an immovable cultural property and is also on the list of cultural assets of the Republic of Croatia for inclusion on the UNESCO World Heritage List, developmental stagnation, continuous demographic decline, decay of part of the valuable building stock, inappropriate interventions on individual houses and the emergence of radical intervention initiatives in a time of change demand a systematic and comprehensive evaluation of the town’s cultural heritage. This article presents a methodology for the analysis of a cultural landscape using the example of Lubenice. The methodological approach is based on the analysis of the historical development and of natural, urban and architectural features of the cultural landscape. The components of the cultural landscape were evaluated using general and specific criteria. Conducting an evaluation according to this methodology provides guidelines for future interventions in order to improve the preservation of historic heritage and prevent damage by future interventions, while ensuring sustainable development.

1. Introduction

The circumstances in which the world finds itself and the changes experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic pose numerous challenges to planners. The opening up of teleworking opportunities to a growing number of employees and the need for social distancing have prompted people to consider relocating from densely populated urban areas to less populated urban or even rural areas. Such isolated or peripheral areas that have become depopulated have renewed potential and are becoming more desirable places to live. A sense of connection with the landscape and a low density population allow people greater freedom of movement and a sense of security in a pandemic.

Since such sparsely populated areas, and especially small historic towns, are very sensitive, we need high quality sustainable development strategies to avoid misguided spatial interventions. Impetuous decisions relating to development could lead to the devastation of small historic towns and the loss of cultural diversity and heritage. Making appropriate decisions is crucial because this type of heritage represents significant development potential for Europe [1,2,3,4].

Cultural heritage is of great value to society from a cultural, environmental, social and economic point of view and is confronted with important challenges related to present day transformations. In all its diversity, it represents an important source of identity, innovation and creativity. It plays a unique role in achieving the Europe 2020 strategy goals for ‘smart, sustainable and inclusive growth’ because it has social and economic impact and contributes to environmental sustainability. The role of cultural heritage in sustainable development must be enhanced on different levels, focusing primarily on urban and rural planning, redevelopment and rehabilitation projects. Cultural heritage must be seen as an asset in spatial planning, the construction of buildings and development of territories, and its protection against a variety of threats is the goal of a dedicated set of actions under the third pillar of the European Framework for Action on Cultural Heritage, namely ‘Cultural heritage for a resilient Europe’ [5,6,7].

The cultural landscapes of small Mediterranean towns are important elements of Europe’s cultural heritage. As stated in The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, the term ‘cultural landscape’ embraces a diversity of manifestations of the interaction between humankind and its natural environment. Cultural landscapes often reflect specific techniques of sustainable land use, considering the characteristics and limitations of the natural environment they are established in, and a specific spiritual relation to nature. Cultural landscapes fall into three main categories, namely (1) a clearly defined landscape designed and created intentionally by people; (2) an organically evolved landscape, and (3) an associative cultural landscape [8].

The natural, architectural and intangible heritage of small Mediterranean towns is a fundamental resource for development and quality of life, with the unique cultural, natural, economic and social characteristics of towns and their landscapes determining their individuality and value. Although small Mediterranean towns, with their centuries-old urban traditions, are an important component of the spatial identity of European countries, and their protection and maintenance are of great importance for the preservation of national culture, changes in their historical role and the degree of their urban significance often endanger their urban structure and spatial integrity.

The causes of endangerment lie in a neglected economic base and a lack of interest in heritage, and in overdevelopment and inappropriate methods of restoring historic structures, in both cases causing the loss, decay or degradation of the inherited value of the historic urban environment and associated landscapes. Considering that heritage is a ‘non-renewable resource’, it is necessary to recognize its value [9] in order to sustain the significance of this heritage and establish the preconditions for sustainable development.

In addition to the economic, social and environmental aspects, the elaboration of a sustainable development strategy requires an emphasis to be placed on the preservation and active use of historical heritage in accordance with The Historic Urban Landscape approach [10]. Of particular importance for future development is the definition of possible models for the revival and enhancement of heritage, which must be determined in accordance with the factors of identity, influence and value as well as in harmony with the criteria for new interventions [11]. Defining a development vision of a small historic town and elaborating its sustainable development strategy also demands special consideration of the carrying capacity of the settlement and its cultural landscape [12,13]. Special care in this sense must be taken regarding cultural tourism, since this, as one of the largest and fastest-growing global tourism markets, can lead to ‘touristification’, ‘tourism gentrification’ and, more recently, ‘overtourism’ [14,15,16,17].

The analysis and evaluation of the cultural landscape of the settlement of Lubenice on the island of Cres in Croatia conducted in this article, based on a set methodology, provides a case study for recognition of the unique heritage value of a small Mediterranean town. The settlement of Lubenice was selected as a valuable example, with a unique landscape and urban and architectural features that pose a variety of challenges regarding future development.

This article presents a methodology for the analysis and evaluation of the elements of the historical identity and features of the cultural landscape of a small historic town using the example of Lubenice. Conducting an evaluation using this methodology provides the foundations and guidelines for future interventions in order to improve the preservation of heritage and prevent potential damage by such interventions while ensuring sustainable development.

The settlement is protected as an example of immovable cultural heritage and since 2005 has been listed on UNESCO’s tentative list under Selection criteria V (an outstanding example of a traditional human settlement, land-use, or sea-use which is representative of a culture (or cultures), or human interaction with the environment especially when it has become vulnerable under the impact of irreversible change [18]), which clearly indicates that the primary value of Lubenice’s cultural heritage lies in the preservation of the entirety of the space created by the interrelationship of human activity and natural features throughout history, making it a valuable example of a cultural landscape. The settlement of Lubenice is characterized by a compact urban space on a natural elevation above the Adriatic coast and an agrarian landscape, with which the settlement forms a unique and recognizable spatial unit. Following development stagnation, continuous demographic decline, the partial decay of the valuable building stock, inappropriate construction interventions on individual buildings and the emergence of radical intervention initiatives such as the transformation of the settlement into a dispersed hotel, it is necessary to determine a well-defined strategy for future development. As a precondition for the preservation of Lubenice’s inherited values, an analysis of the historic cultural landscape using contemporary methodology must be conducted in order to identify its unique heritage characteristics and draw up guidelines for sustainable development.

The aim of this paper is to present a methodology for the analysis of the elements of the historical identity and features of the cultural landscape of a small historic town as a basis for a sustainable development strategy. The methodology enables the identification of the unique values of historic small towns in order to determine the most appropriate manner of development in the future. Conducting an analysis using this methodology provides the foundations and guidelines for future interventions in order to improve the preservation of cultural and natural heritage while ensuring sustainable development. This is especially important due to pressures on small historic towns, which are becoming more attractive to live in during times of change.

2. Material and Methods

This article presents the methodology of the analysis and evaluation of the cultural landscape features of a small historic town as a key element in the development of its sustainable development strategy. The methodology is employed in the analysis and evaluation of the cultural landscape features of the historic Mediterranean town of Lubenice on the island of Cres in Croatia.

The methodology is based on the Historic Urban Landscape Approach (HUL), regulating the conservation and development of historic urban landscapes such that they do not lose their qualities and the historical significance. The HUL approach aims at preserving the quality of the human environment, enhancing the productive and sustainable use of urban spaces while recognizing their dynamic character, and promoting social and functional diversity. It integrates the goals of urban heritage conservation and those of social and economic development [19,20]. The methodology furthers the contributions of previous researchers in the field of cultural landscapes [21,22,23,24,25,26].

The focus of the research is to emphasize the connection and unity of the architectural, urban and natural landscape features as components of the cultural landscape (considering that none of the components or aspects alone would represent heritage value comparable to the most valuable domestic or international examples). Highlighting the unique value of the cultural landscape of historic towns and underlining the significance of the integral protection of all elements ensures the preservation of the cultural landscape and its sustainable development.

The methodological approach is based on two basic elements of analysis. The first element is an analysis of historical development and the second element is an analysis of the contemporary natural, urban and architectural features of the cultural landscape.

The analysis of historical development was carried out on the basis of available bibliographic and cartographic data. It enables an understanding of the process of settlement and the formation of specific features, depending on the occupation of space and building construction in certain historical periods, demographic and sociological aspects (urban/rural lifestyle, population and size of the settlement in certain historical periods), economic aspects (periods of growth, periods of stagnation and/or decline) and geopolitical and strategic aspects (the affiliation of the settlement with different countries and/or larger settlements in certain historical periods, the significance of the settlement and its position in the regional defense system, control of trade routes, etc.).

An analysis of the natural, urban and architectural features of the cultural landscape allows for determination of the following:

- Landscape types, which are determined by superimposing cartographic data of historical and present land use, topographic features, geological and hydrographic features and conducting visual exposure analysis.

- Urban structure types, which are determined by analyzing the settlement layout, urban matrix, the silhouette from surrounding viewpoints and the characteristic urban patterns.

- Architectural types of the building stock, which are determined by the historical and present purpose, date of construction, architectural style, location of the building on its plot, history of adaptations, spatial organization, type of construction and building materials, facade design, building condition and degree of preserved originality.

The evaluation of individual types of components of the cultural landscape is carried out on the basis of set general and individual criteria. Five general criteria were established for evaluation: integrity, authenticity, current condition, age value and development potential. Integrity represents a completely preserved urban/natural space and building structure, without subsequently introduced degrading elements. Authenticity represents the degree of preservation of original architectural and urban structures and landscape units. The current condition refers to the construction and technical condition of buildings, the preservation of the silhouette and the urban matrix, as well as the design and use of landscapes. The age value refers to dating the construction of individual buildings and the formation of the urban matrix as well as to the continuity of contact landscape land use. Development potential relates to the possibilities for modern use of the existing building stock, the way the community and the individuals can function in a particular settlement (during the pandemic) and maintaining the continuity of traditional land use, which supports biological diversity.

Individual evaluation criteria are defined for each cultural landscape type (shown in detail in Table 1) on the basis of which of the individual components of each type are analyzed and presented in Section 4.

Table 1.

General and specific criteria for evaluation of cultural landscape.

Results of the analysis according to the set methodology should serve as one of the criteria for decision making on future interventions at a particular location.

3. Results: Small Town of Lubenice on the Island of Cres

This chapter presents the results of the analysis and evaluation of the small historic town of Lubenice on the island of Cres (Figure 1). The results are structured according to the proposed methodology, including an analysis of the historical development and an analysis of the landscape, urban and architectural features of the settlement.

Figure 1.

Position of Lubenice on the island of Cres in Croatia. Map by the authors.

3.1. Historical Development of Lubenice

In prehistoric times, the settlement of Lubenice was a strategically important Illyrian and Liburnian hill fort, the existence of which has been confirmed by tumuli (tombstones) from the Bronze and Iron Age on the surrounding highlands. In ancient times, Lubenice was referred to as Hibernitia (winter/cold settlement), one of the four most important settlements on the island of Cres that had a fully formed urban core. At the foot of the settlement, there was a significant villa rustica with surrounding agricultural land and a harbor on the seashore. In the Middle Ages, the settlement became the seat of the parish, and the basic spatial composition of the settlement was established. The town was fortified by the construction of walls on the east perimeter, with town gates to the north and south. The urban matrix was defined, with two longitudinal streets along with three agglomerations of houses organized around communal inner courtyards (piazzetta). In these courtyards, public and private use was intertwined; they were public in terms of access to all buildings and private in terms of use of outdoor space, in keeping with the Mediterranean way of life [27].

During the Renaissance and Baroque periods, a series of public and sacral buildings were built on the medieval urban matrix, together with residential buildings of high aesthetic quality, forming a unique spatial composition and urban silhouette.

The settlement had the status of a commune until the end of the 15th century, when it fell under the jurisdiction of the town of Cres [28]. The general progress of development on the island of Cres in the 18th century and at the end of the 19th century resulted in an increase in the population and the further expansion of the settlement beyond the fortified perimeter towards the north and south. At the end of the 19th century, a second floor had been constructed on most houses within the town center.

Economic development, accompanied by construction activity on sacral and residential buildings, as well as maintenance and the minor expansion of existing houses, continued in the early 20th century, while in the second half of the 20th century, as a result of forced industrialization and anti-agrarian policy, there was a marked stagnation and depopulation of the settlement. The trend of stagnation and depopulation continued in the early 21st century, which is clearly evident from the fact that, according to the 2021 census [29], Lubenice has only six permanent residents in five households.

3.2. Analysis of the Landscape, Urban and Architectural Features of the Settlement of Lubenice

This subchapter presents the results of the research, structured to present the elements of landscape features, urban features and architectural features.

3.2.1. Landscape Features

The cultural landscape of Lubenice is made up of units whose features clearly indicate the genesis of the space, conditioned by the physical limitations of the topography as well as the social and economic factors of particular periods of urban development [30]. The entry of the Historic Urban Unit of the Lubenice Settlement in the Register of Cultural Property of the Republic of Croatia—List of Protected Cultural Assets in 2006 determined a zone of complete protection of historic structures for the settlement itself, as well as a buffer zone for the wider area, but without a detailed characterization of the landscape or typological classification. Considering the size of the buffer zone and the diversified character of the landscape within it, a detailed landscape inventory and description must be carried out as a prerequisite for evaluation and the determination of future development guidelines.

By superimposing cartographic data on historical land use (a Franciscan cadastre from 1821 and a cadastral map from 1830) on present day land use (based on a digital orthophoto map, digital cadastre and ‘Corine Land Cover’), topographic data (based on topographic maps and a GIS digital model of the terrain), geological and hydrographic features of the area (based on the Basic Geological Map of the Republic of Croatia) and analysis of the visual features of the city and the landscape, the characteristic landscape types and subtypes/patterns in the buffer zone were determined.

The typological classification covers a number of aspects and identifies seven landscape types with eight characteristic subtypes and twelve landscape patterns, which are graphically presented and whose landscape features are described.

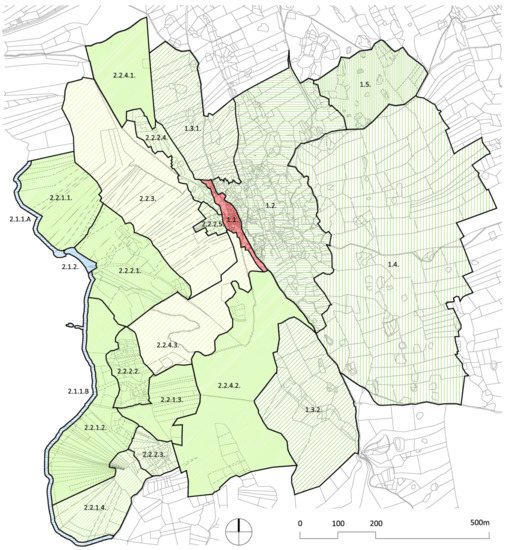

The settlement of Lubenice is located in the central eastern part of the island of Cres, in the area between Lake Vrana and the sea coast. The urban core of the settlement is situated on a rock ridge that forms a dividing line between two different landscape units on the island of Cres. The eastern unit is characterized by an elevated position and separation from the sea, fertile soil and small settlements with associated cultivated valleys, while the western unit is characterized by visual openness to the sea and uninhabited, steep and mostly wooded (western) slopes [31]. An analysis of the landscape features in the eastern landscape unit determined the following landscape types, subtypes and patterns (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Lubenice cultural landscape types, subtypes and patterns. Map by the authors.

- The historic urban landscape (1.1)

The historic settlement of Lubenice is situated on a rock ridge, at an altitude of 380 m above sea level. It has a compact urban form defined by medieval town walls. The organic urban matrix of residential houses is organized along two main streets, which in their eastern part start from the town square where the church, former town loggia and bell tower are located. The western point of the settlement is marked by the town cemetery and a chapel. Due to its acropolis position, the settlement is visually exposed to the wider terrestrial and marine environment and forms a distinctive panoramic image with characteristic urban shapes and outlines.

- The historic agrarian valley landscape east of the settlement (1.2)

The historic agrarian valley has a number of “ponikve” (sinkholes, circular recesses with steep sides, mostly in the form of a funnel). Today, it has natural plant cover on terraced surfaces, bounded by a small network of dry stone walls, with auxiliary buildings and a network of field paths. The terraces were once cultivated with traditional cultures: olives, vines and grains; today, they are left to the succession of macchia. Due to the wild vegetation and a lack of maintenance of the agricultural land, the visual pattern of dry stone walls has been lost (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

(a) Landscape type 1.2. The historic agrarian valley landscape east of the settlement. Photo by the authors. (b) Landscape type 2.2. The sloping landscape. Photo by the authors.

- The historic slope of pastureland north of the settlement (1.3.1)

A slight northeast slope with long dry stone walls defining large, regular rectangular spaces. They spread over the localities of Ograda and Presleh and were used as pastures with scarce vegetation. Today, they are hardly used, and the characteristic landscape pattern of pastures has been transformed into natural vegetation, with the succession of macchia and forest.

- The historic slope of pastureland south of the settlement (1.3.2)

A gentle northeast slope with rectangular long, dry stone wall regulation at the Hrib locality, still clearly visible despite extensive natural vegetation; the landscape pattern of the former pasture has been retained.

- The historic hilly pasture landscape (1.4)

A hilly area, historically used for pasture, with a network of dry stone walls with a relatively large, almost rectangular pattern. The dominant topographic feature is hilly terrain with slight slopes, sinkholes and sparse vegetation. The northern edge of this area is delineated by a road leading from Lubenice to the village of Žbičina, bounded on both sides by dry stone walls. Among the historic anthropogenic structures, the prehistoric mound (tumulus) at the Vrh sela locality and the medieval chapels of St. Mihovil and St. Petar stand out.

- The historic hilly agrarian and forest landscape (1.5)

A hilly area, historically of mixed use, mainly covered by coniferous forest, with a fragmentary network of dry stone walls, located north of the road to nearby Žbičina village.

In the western landscape unit, the following landscape types, subtypes and patterns have been identified:

- Coastal landscape (2.1)

A landscape unit that extends in a narrow belt along the entire area, featuring two patterns: the natural rocky coast (2.1.1) and the natural pebble beach (2.1.2). The beach, coastal belt and slopes are strongly involved in the characteristic panoramic image of Lubenice from the sea.

- Sloping landscape (2.2) (Figure 3b)

Landscape that includes several different subtypes and patterns, which define its structure and visual appearance: forested and macchia-covered slopes (2.2.1), agriculturally cultivated slopes (2.2.2) and historic steep slopes (2.2.3).

The dominant feature of this area is geomorphological and natural: a steep slope covered with forest and macchia in the lower parts and hilltops without vegetation, with particular emphasis on the geological structures of bare, rocky cliffs. Smaller areas near dried-up small streams were agricultural, cultivated with olive groves and vineyards. Today, these areas have been left to the succession of wild vegetation. Anthropogenic elements in the space are the medieval chapel of St. Ivan, located in the Pod Lubenice locality, paths leading to previously agricultural land and to the bay, and archaeological remains (a villa rustica with mosaic remnants and other archaeological findings of material culture—amphorae, coins and jewelry). Immediately adjacent to the western town ramparts are small terraced gardens surrounded by dry stone walls.

3.2.2. Urban Features

The analysis of urban features refers to the historic urban core of the settlement, analyzing its overall layout (to determine the conditioning of the location and the shape of the settlement by its historical genesis, the relationship between the built structure and topography, traffic system, etc.), its urban matrix (built structure, traffic system and public spaces), silhouettes from surrounding vantage points and characteristic urban patterns.

An important part of the heritage value of Lubenice lies in the complete preservation of the medieval urban matrix and spatial composition (silhouettes) of the settlement, as well as the intact preservation of the historic urban fabric with traditional residential architecture, sacral buildings, public spaces and fragments of the medieval fortification system. The urban core has an irregular, elongated oval layout, determined by the morphology of the terrain (the edge of a cliff) to the west, by the perimeter of medieval walls to the east, by the town square with the most significant public and sacral buildings to the south and by a rocky plateau between the urban core and the cemetery.

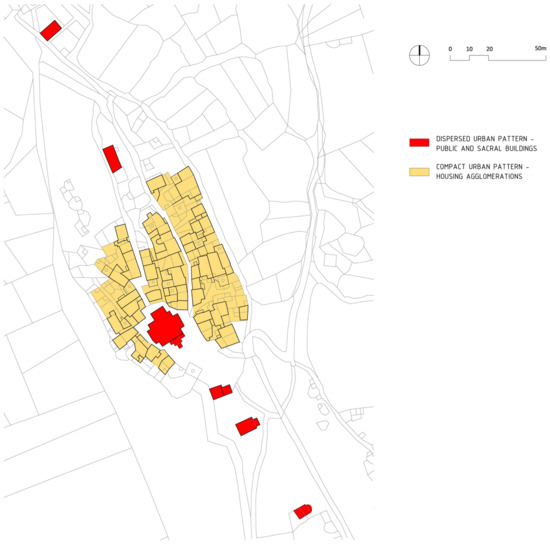

There are two basic types of urban structure in the urban core: the compact urban pattern in the central part (A) and the dispersed urban pattern in the northern and southern parts (B1 and B2) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Urban patterns. Map by the authors.

- Compact urban pattern

The compact urban pattern is formed by traditional residential buildings in three linear agglomerations, spatially defined by the eastern and western perimeter of the urban fabric and by two main longitudinal streets running northwest–southeast. The residential agglomerations are characterized by a marked compactness/density (terraced and semi-detached houses), determined by the small scale of building plots and by the functional organization of buildings around internal courtyards, which creates a distinct urban pattern.

Public space in the central part of the urban core comprises two parallel main streets, with proportions characteristic for the medieval cores of Mediterranean towns (width to height ratio less than 1:1, covered passages, etc.) and is primarily of a pedestrian character, while internal courtyards (some separated from the street by walls with stone portals) create semi-public spaces (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

(a) Compact urban pattern. Photo by the authors. (b) Dispersed urban pattern. Photo by the authors.

- Dispersed urban pattern

The dispersed urban pattern is composed by public, sacral and communal buildings and public spaces in the northern and southern parts of the urban core.

In the southern part, the parish church, the bell tower, the town loggia and the municipal water cistern define the perimeter of the main square. The edges of the parking plateau, situated south of the square, are defined by two medieval chapels (St. Antun and St. Nedjelja), while in the northern part of the settlement, in a mostly unbuilt area, is the former school building and a cemetery with the chapel of St. Stjepan.

The urban structure of areas with a dispersed urban pattern is characterized by low density construction, with freestanding buildings on large plots surrounded by public space. The southern area, with a dispersed urban pattern, is defined by the town square, public and residential buildings with views over the sea to the west and over the agricultural landscape to the east, and a main access road and parking area between two medieval chapels. The northern area, with a dispersed urban pattern, is characterized by an unbuilt rocky plateau between a former school building and a chapel (Figure 5b).

3.2.3. Architectural Features

The first step in determining the architectural features of the built structure is an analysis of individual buildings, which includes the time of construction, architectural style, situation on the building plot, history of construction and adaptations, historical and current purpose, internal spatial organization, construction type and building materials, facade design, building condition and degree of preservation of the original building. This analysis creates the basis for evaluation according to the previously defined value categories.

The analysis of individual buildings enables the creation of a database of comparable information. Using this data, the classification of particular building types can be carried out, and the characteristic architectural features of each type can be determined.

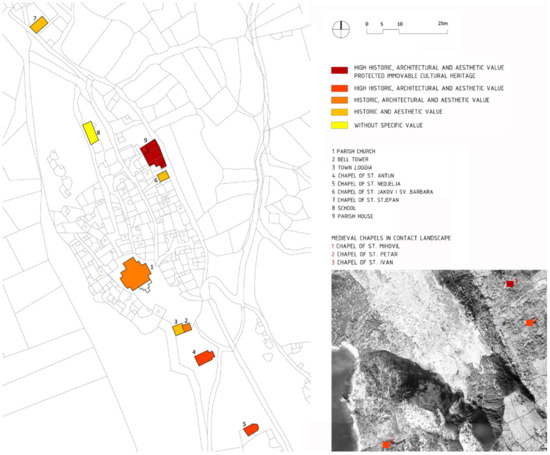

The analysis of the individual buildings in Lubenice identified four building types according to their purpose: (1) public and sacral buildings, (2) residential buildings (3) fortifications, and (4) public spaces. It determined the characteristic architectural features of each type with regard to the construction period, architectural style, layout and spatial organization, building materials, degree of originality and present use.

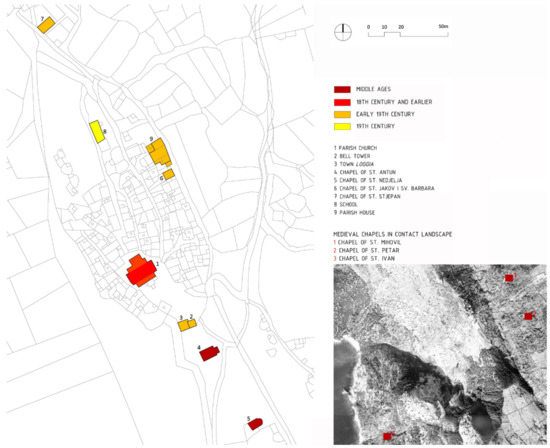

- Architectural features of public and religious buildings

Public and sacral buildings in the Lubenice settlement show historical stratification, with chapels in the contact landscape and the peri-urban area mostly built during the Middle Ages, while buildings in the northern and southern part of the urban core were mostly built during the 18th century (parish church, bell tower, town loggia, clergy house, chapel of St. Jakov and St. Barbara) and in the first half of the 19th century (school building).

Due to the variety of construction periods of individual buildings, elements of different historical architectural styles are present, from Romanesque (chapel of St. Nedjelja), Gothic (chapels of St. Antun, St. Mihovil, St. Petar and St. Ivan) and Baroque (parish church, bell tower, clergy house and chapels of St. Stjepan, St. Jakov and St. Barbara), through to the style of the 19th and early 20th century (school building) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Construction period of public and religious buildings. Map by the authors.

Public and religious buildings are freestanding, with the exception of the semi-detached chapels of St. Jakov and St. Barbara and the interconnected structures of the bell tower and the town loggia.

Most of the buildings are comprised of a single space, with a simple cross-section and rectangular ground floor plan. Medieval chapels have a rectangular or semicircular apse; exceptions are the three-naved parish church with a basilic cross-section, the clergy house complex and the four-story bell tower.

The walls of public and sacral buildings are made of stone; some are plastered with lime mortar and some have exposed stone masonry (chapels and the southern part of the clergy house complex).

Most of the buildings have gabled roofs (with the exception of the bell tower, with its pyramidal roof, and the town loggia with its single pitched roof), with original stone slate or terracotta roof tiles.

All public and sacral buildings in the urban and peri-urban area have been maintained and preserved (except for the chapel of St. Nedjelja and the southern part of the clergy house), while the medieval chapels in the contact landscape have not been maintained (the chapel of St. Mihovil is dilapidated/partially damaged and in need of restoration, while the chapels of St. Petar and St. Ivan are dilapidated).

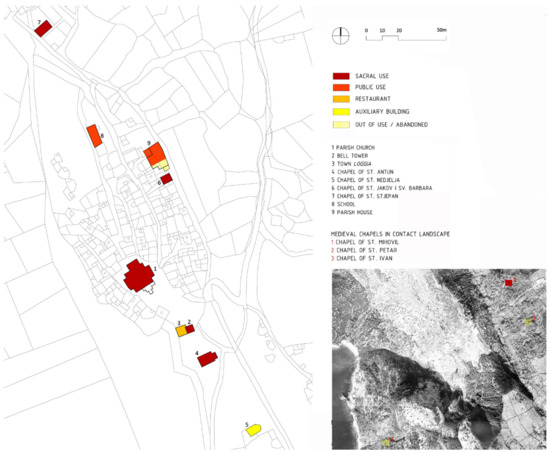

Chapels in the contact landscape, the bell tower and the chapel of St. Antun have been retained in their original condition. The parish church has preserved layers of historical alterations, while the school building, clergy house and chapel of St. Nedjelja have been partially altered (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Condition of public and religious buildings. Map by the authors.

Some of the sacral buildings have retained their original purpose. The clergy house is currently used as an exhibition space, the chapel of St. Nedjelja is used as an auxiliary building, and the chapels in a dilapidated state (the chapel of St. Petar and St. Ivan) have no function. The former school building has retained its public use and is now used as an NGO headquarters, while the town loggia has been transformed into a restaurant (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Current use of public and religious buildings. Map by the authors.

- Architectural features of residential buildings

Residential buildings in the town’s core form three linear agglomerations, with a compact urban structure characterized by semi-detached and terraced houses organized around internal courtyards. Most of the houses were built during the 18th and early 19th centuries on the basis of the archetypical house of the island of Cres, characterized by a simple rectangular floor plan, with the addition of functional external building elements such as external staircases, fireplaces and water cisterns. Houses were originally two-storied, with a room used as a cellar on the ground floor and living space on the upper floor. This has been retained in a small number of examples, while most of the houses were altered by the addition of a second floor during the 19th century. Walls were made from local broken stone, arranged in an irregular style, originally with a lime mortar finish. The principal buildings had gabled roofs, while the roofs of exterior buildings (annexes) were single-pitched. Roofs had traditional stone slate cladding and stone gutters (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Construction period of residential buildings. Map by the authors.

The distinctiveness of the housing in Lubenice is expressed through an upgrade of the archetypal architectural expression by the use of elements such as impressively shaped crowns on external water cisterns, exterior staircases, prominent chimneys, wooden pergolas with stone supports over water storage terraces, stone portals and vaulted street aisles. Houses in which such building elements have been used are the most valuable examples of the housing stock (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Stone portal and vaulted street aisle in the central housing agglomeration. Photo by the authors.

A small number of buildings are used for tourism, while the majority of the housing stock is used as permanent or periodical housing; almost half of the buildings are neglected, i.e., disused. The housing stock has a strong potential for year-round usage, not just as tourist apartments during the summer (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Current use of residential buildings. Map by the authors.

- Architectural features of fortifications

The medieval fortification system of untreated stone walls that defined the northern, eastern and southern perimeter of the Lubenice urban core is today preserved in fragments: in the northern part, as a long, isolated stretch of walls along the access road to the cemetery, and in the eastern part, as fragments of freestanding walls or walls that formed the basis of houses that were later built. The north and south town gates have been preserved.

The architectural logic of the stretches of the fortification system on the northern, eastern and southern perimeter of the medieval town suggests the existence of town walls in the southern part of the urban core; for their precise determination and possible presentation, additional archaeological research would be needed (Figure 12 and Figure 13).

Figure 12.

City fortification elements. Map by the authors.

Figure 13.

Part of northern city gate and medieval wall. Photo by the authors.

- Architectural features of public spaces

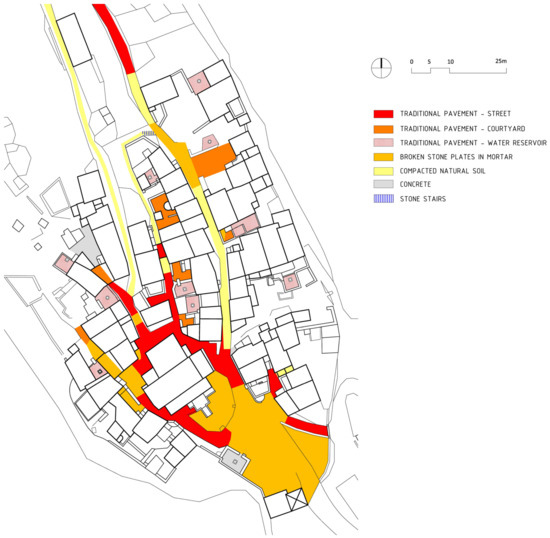

Lubenice public spaces comprise an access square in the southern part of the urban core, two main streets leading from the square towards the northern part of the settlement (the western street leading towards the former school building and the eastern towards the town cemetery) and a passage through the central housing agglomeration. The access square has an irregular layout, with a slight fall towards the south, and is paved with broken stone slabs laid in cement mortar, without any elements of surface drainage. A communal water cistern with a stone crown and edged with stone walls forms an integral part of the square (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Public and semi-public space pavement types. Map by the authors.

The streets are characterized by the partly preserved original pavement, with broken or partially carved stone elements laid vertically and without mortar (smaller, irregular stones used for streets and larger, shaped stones for internal courtyards and terraces of external water cisterns) (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Fragment of original street pavement. Photo by the authors.

The analysis of the landscape, urban and architectural features determined the types of components of the cultural landscape in the settlement of Lubenice (Table 2). Based on the evaluation of individual types of components according to general and specific criteria, an integral valuation was carried out, the results of which are presented in the discussion.

Table 2.

Types of cultural landscape component, defined by the analysis of the landscape, urban and architectural features of the settlement of Lubenice.

4. Discussion

The results of the analysis enable an evaluation to be made of individual elements, according to the previously defined value categories and groups.

The following value categories have been selected for the evaluation of landscape units: evident (archaeological, architectural, urban and environmental), aesthetic, documentary, cultural, symbolic, socio-economic, natural and ecological. The cumulative value of all these values is expressed as cultural significance, with the cultural significance (degree of value) proportional to the degree of sensitivity to changes in the landscape [32,33].

According to the above criteria, the historic urban landscape of the settlement (1.1), the coastal landscape (2.1) and the slope landscape (2.2) are of very high value and thus have a very high degree of sensitivity to change in the context of Lubenice’s cultural landscape. High value and a high degree of sensitivity to change are characteristic for the historic agrarian valley landscape east of the settlement (1.2) and the historic hilly pasture landscape (1.4), while the historical slopes of pastureland (1.3) and the historic hilly agrarian and forest landscape (1.5) have moderately high value and a moderately high sensitivity to change.

Based on this analysis, evaluation and characterization, it can be concluded that the wider area surrounding Lubenice represents a very valuable, organically evolved, continuing cultural landscape, which clearly reflects specific techniques of sustainable land use, considering the characteristics and limits of the natural environment in which they are established and a specific spiritual relation to nature.

The original urban features of Lubenice have been completely preserved and, as such, are of high visual, historical and environmental aesthetic value, both in terms of the town’s urban layout and silhouette and of the preservation of the urban matrix and characteristic urban pattern of housing groups organized around semi-public (internal) courtyards. Due to the high visibility from the surrounding landscape, the urban features have a high sensitivity to change.

The evaluation of architectural elements was carried out on the basis of several criteria: historical/documentary, archaeological, architectural, urban and environmental aesthetic value. According to the above criteria, in the category of public and sacral buildings, two medieval chapels in the southern part of the urban core (St. Antun and St. Nedjelja), one chapel in the contact landscape (St. Mihovil) and the clergy house complex are of high historical, architectural and environmental aesthetic value and thus have a high degree of sensitivity to change. The parish church and bell tower have historical, architectural, environmental aesthetic and symbolic value; the medieval chapels of St. Petar and St. Ivan have historical, architectural and environmental aesthetic value, while the town loggia and the chapels of St. Jakov and St. Stjepan have only environmental aesthetic value (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Evaluation of public and sacral buildings. Map by the authors.

Houses in the urban core mostly belong to the same historical stratum and are of the same traditional building type, with the exception of houses built on the medieval fortifications and a few buildings that bear the architectural characteristics of town houses. Several 19th century buildings located in the northwestern part of the town are of slightly lower historical and architectural value. Particularly valuable elements of the residential architecture are common residential courtyards with stone walls and portals, vaulted passageways, functional external building elements (fireplaces, stone-paved exterior water reservoirs, chimneys of prominent dimensions and various shapes), and architectural details such as stone gutter supports, stone rings for mounting wooden pergolas over the terraces of water cisterns, wooden racks for drying fruit, etc. (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Evaluation of residential buildings. Map by the authors.

The preserved elements of the fortification system represent cultural and historic heritage of high historical, architectural and aesthetic value, and as such have a very high sensitivity to change.

The original pavements of public and semi-public spaces (squares, streets and common courtyards), with broken or partially-carved stone elements laid vertically and without mortar, is of architectural value and documents a historic construction technique.

Methods of the analysis and evaluation of historical landscapes and townscapes such as Landscape Character Assessment [34], Historic Landscape Characterization [35], Urban Morphology [36], Space Syntax [37], etc., consider the phenomenon of landscape and urban morphology separately. Given the specificities of small historic towns, the presented methodology strives to enhance the integral perception of all elements of space from the scale of architecture to the scale of landscape, continuing previous research that strives toward a holistic and multidisciplinary approach [38].

5. Conclusions

The Lubenice cultural landscape, due to its historical, documentary, architectural, urban, landscape and archaeological value can be rated as of very high or exceptional value and thus classified as having international significance.

The high cultural, historical, urban, architectural, aesthetic and landscape value of Lubenice in relation to other island settlements is in the blend of urban and rural features, with urban features visible in the organization of buildings along streets and around common courtyards, the preserved original silhouette of the settlement, compact urban structure within medieval fortifications and architectural elements on individual buildings (stylistic profiles of windows and doors, carved stones on corner building walls, arched aisles characteristic of the medieval historic nuclei of coastal and island towns, etc.).

Lubenice stands out in the broader spatial context as one of the smallest historical urban units continuously populated from prehistoric times to the present day and due to its historic compactness as a fortified town in a preserved cultural landscape.

The exceptional value of the Lubenice cultural landscape lies in the preserved historical fabric of the town, the architectural details, the composition of the buildings and the location of the urban core on a strategic location at the top of a steep cliff amidst a spacious, centuries-old agricultural landscape with impressive vistas (from the town and of the town). The equilibrium of spatial elements at all levels (from architectural to landscape elements) in such an environment is extremely fragile, susceptible to disruption with each ‘addition’ or modification.

This fragile balance makes the Lubenice area highly valuable, sensitive and demanding for revitalization, which must be based on the preservation of the unique, integrated value of the cultural landscape, evaluated by the above-described methodology.

Future protection and development planning requires special attention to be paid to the protection of the urban structure and its silhouettes from surrounding vistas. The vistas from the southern approach to the settlement, from the sea and from the famous beach beneath the town are especially important to the identity of the settlement. Encouraging traditional agriculture, such as orchards, olive groves and pastures, within the system of dry stone walled plots in the valley east of the settlement and the traditional vineyards on the steep slopes west of the settlement, can maintain the value of the natural landscape and support biological diversity.

In order to establish potentially applicable models for the revival and enhancement of Lubenice’s heritage in accordance with the factors of identity, influence and value, and in harmony with the criteria for new interventions, it is advisable to conduct a comparative analysis of selected relevant examples (case studies) to determine historical and modern models in similar situations, which will guarantee the selection of the best model for a specific case.

Definition of a development scenario, whether it is based on the introduction of a new type of permanent use or the introduction of tourist use, i.e., development based on cultural tourism, requires the determination of the carrying capacity of the settlement, so that new activities and interventions do not significantly disturb the inherited natural, built and socio-cultural environment.

The proposed methodology of analysis and evaluation of the cultural landscape, which takes into account the unity of the architectural, urban and landscape features, should be taken as a starting point for a long-term development strategy, supplemented by other transdisciplinary analytical frameworks in order to preserve its uniqueness and vitality in times of change.

The scientific contribution is the establishment of an integrated method of analysis and evaluation of the cultural landscape that equally considers individual buildings, the urban structure and the contact landscape. The above-described methodology enables the definition of guidelines for the sustainable development of small historic towns at a time of an evident increase in interest, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The methodology is primarily applicable for the analysis and valuation of small historic towns. For application in larger cities and rural settlements, the method should be adapted and supplemented with additional spatial components.

In future scientific research, the method of analysis and evaluation could be used alongside qualitative assessment and quantitative valuation of elements of the cultural landscape. Furthermore, the above methodology could be adapted for research on the cultural landscape of large cities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K. and L.P.K.; methodology, D.K., L.P.K. and B.D.B.; formal analysis, D.K. and L.P.K.; investigation, D.K., L.P.K. and B.D.B.; resources, D.K. and B.D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K. and L.P.K.; writing—review and editing, D.K., L.P.K. and B.D.B.; visualization, D.K. and L.P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- European Council. The New EU Strategic Agenda 2019–2024. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/39914/a-new-strategic-agenda-2019-2024.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Europa Nostra. Work Plan for Culture 2019-2022: EU Ministers of Culture Make the Legacy of the European Year a Priority. Available online: https://www.europanostra.org/work-plan-for-culture-2019-2022-eu-ministers-of-culture-make-the-legacy-of-the-european-year-a-priority/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- European Commission. The New European Agenda for Culture. Available online: https://www.cultureinexternalrelations.eu/cier-data/uploads/2018/06/commission_communication_-_a_new_european_agenda_for_culture_2018.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- European Commission. The New Leipzig Charter-The Transformative Power of Cities for the Common Good. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/newsroom/news/2020/12/12-08-2020-new-leipzig-charter-the-transformative-power-of-cities-for-the-common-good (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- European Commission. The European Framework for Action on Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/5a9c3144-80f1-11e9-9f05-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Conclusions of 21 May 2014 on Cultural Heritage as a Strategic Resource for a Sustainable Europe. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014, 183, 36–38. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52014XG0614%2808%29 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Council Conclusions on Risk Management in the Area of Cultural Heritage, 8208/20, the European Framework for Action on Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/44116/st08208-en20.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- DeSilvey, C.; Harrison, R. Anticipating loss: Rethinking endangerment in heritage futures. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fusco Girard, L. Toward a Smart Sustainable Development of Port Cities/Areas: The Role of the Historic Urban Landscape Approach. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4329–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Obad Šćitaroci, M. The Heritage Urbanism Approach and Method. In Cultural Urban Heritage: Development, Learning and Landscape Strategies; Obad Šćitaroci, M., Bojanić Obad Šćitaroci, B., Mrđa, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. V–XIV. [Google Scholar]

- Canestrelli, E.; Costa, P. Tourist carrying capacity. A Fuzzy Approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 1991, 18, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. The concept of carrying capacity for tourism destinations: Dead or merely buried? Prog. Tour. Hosp. Res. 1996, 2, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, S.M. Tourism Management in World Heritage Sites and its Impact on Economic Development in Mali and Ethiopia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 211, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCain, G.; Ray, N.M. Legacy tourism: The search for personal meaning in heritage travel. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Hoa, P.S.Y.; Du Cros, H. Relationship between tourism and cultural heritage management: Evidence from Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle-Vaquero, M.d.l.; García-Hernández, M.; Mendoza de Miguel, S. Urban Planning Regulations for Tourism in the Context of Overtourism. Applications in Historic Centres. Sustainability 2021, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Barreiro Martínez, D.; Parga-Dans, E.; Alonso González, P. Democratising Heritage Values: A Methodological Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UNESCO’s Tentative List. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/state=hr (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- UNESCO. Recommendation on Historic Urban Landscape; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. The Valletta Principles for the Safeguarding and Management of Historic Cities, Towns and Urban Areas; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eetvelde, V.; Antrop, M. Integrating Cultural Themes in Landscape Typologies. In European Landscapes and Lifestyles: The Mediterranean and Beyond; Roca, Z., Spek, T., Terkenli, T., Plieninger, T., Höchtl, F., Eds.; Edições Universitárias Lusófonas: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009; pp. 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, K.; Lenon, J. Managing Cultural Landscapes (Key Issues in Cultural Heritage); Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bandarin, F.; Van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rodwell, D. Conservation and Sustainability in Historic Cities; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Scazzosi, L. Reading and assessing the landscape as cultural and historical heritage. Landsc. Res. 2004, 29, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. The Historic Urban Landscape paradigm and cities as cultural landscapes. Challenging orthodoxy in urban conservation. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohorovičić, A. Analiza razvoja urbanističke strukture naselja na otocima zapadnog Kvarnera [An analysis of the development of the urban structure of settlements on the islands of the Eastern Kvarner]. Ljetop. JAZU 1956, 61, 461–493. [Google Scholar]

- Pozzo-Balbi, L. L’Isola di Cherso; A.R.E.: Rome, Italy, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Available online: https://www.dzs.hr (accessed on 24 December 2021).

- Dumbović Bilušić, B. Krajolik kao Kulturno Naslijeđe; Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Croatia: Zagreb, Croatia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Andlar, G.; Kremenić, T.; Križanić, M.; Borovičkić, M. Studija Krajobraza Otoka Cresa; Island Development Agency: Cres, Croatia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brunsden, D.; Thornes, J. Landscape Sensitivity and Change. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1979, 4, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fairclough, G.; Sarlöv Herlin, I.; Swanwick, C. (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Landscape Character Assessment: Current Approaches to Characterisation and Assessment; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, G.J. A new landscape for cultural heritage management: Characterisation as a management tool. In Landscapes Under Pressure: Theory and Practice of Cultural Heritage Research and Preservation; Lozny, L., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, V. Urban Morphology: An Introduction to the Study of the Physical Form of Cities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, S. The Use of Space Syntax in Historical Research: Current practice and future possibilities. Proceedings of Eighth International Space Syntax Symposium, Santiago, Chile, 3–6 January 2012; Greene, M., Reyes, J., Castro, A., Eds.; Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2012; p. 8193. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, J. The Cultural Values Model: An integrated approach to values in landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 84, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).