Using Indicators to Evaluate Cultural Heritage and the Quality of Life in Small and Medium-Sized Towns: The Study of 10 Towns from the Polish-German Borderland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. CBH as a Parameter of Quality of Life in Small and Medium-Sized Towns

- −

- small towns of up to 20,000 residents;

- −

- medium-sized cities of 20,000–100,000 residents;

- −

- large cities of at least 100,000 residents.

- Multifaceted relations between CBH and quality of life exist and can be identified, structured, and measured by indicators. At the same time, the various relations between these phenomena are often intuitively understood and indirectly discussed in numerous studies rooted in various scientific disciplines.

- The relations between CBH and QoL are more visible in small and medium-sized towns lacking other assets characteristic of larger cities.

3. Research Methods

- The literature review, which focused on three thematic areas: QoL, SMTs, and CBH. The relationship between these fields was analysed with the aim of identifying gaps in the current quality of life assessments of historic small and medium-sized towns. From the large number of literature sources, we extracted 22 studies focusing on the quality of life [16,17,18,19,20,21,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76], (see Table A1 in Appendix A). Since the empirical part of our research was aimed at towns located in the transborder area, we focused in particular on studies that are nationally recognized as important for Polish and German urban policy and research. The studies were found, with few exceptions, using internet search engines; no results have been excluded, as long as we considered them to be a studies on the quality of life in cities (some additionally focus on the region). The studies were first selected separately by the German and Polish members of the team and then jointly discussed and approved. The final set of analyses included 11 studies from Germany, 7 from Poland, 1 from Italy, and 3 with an international focus. The Polish and German studies, which were of primary interest to the authors, come from the years 2006–2018. The purpose of the analysis was to explore the extent to which the characteristics relevant to the QoL of historic SMT (in peripheral locations) are taken into account in the evaluation of urban QoL, particularly in Germany and Poland. Most of these studies focused on urban areas, but several also considered the entire country or region without differentiating between urban or rural areas. From 22 studies on QoL, we identified and extracted 412 indicators that we assigned to 10 categories (dimensions) of QoL, i.e., work, living conditions (housing), services for citizens, free time, nature and cultural heritage, health, safety, education and engagement, and society. In the next step, the ten dimensions were compressed into five that better relate to the object of study without limiting the overall scope of the issue. (Table 1).

- Semi-structured interviews and expert workshops. For the scope of the study, we conducted an extended interview (in written form) with five selected German and Polish experts representing the fields of urban regeneration, SMT research, QoL, innovative indicators, and built heritage. In the first phase, the role of the experts was to indicate and assess possible relations between QoL and CBH, as well as to propose the indicators for their measurement according to their fields of expertise. The experts’ opinions, together with the findings of the authors’ literature review, were then confronted and jointly discussed during the workshop. All the results were then summarised, and on this basis, the assumptions on a possible contribution of the built heritage to quality of life in small and medium-sized towns (one attributed to each of the five dimensions mentioned above) were formulated. The third task of the experts was to formulate their opinions on the proposed assumptions (the final set of dimensions and assumptions attributed to them are presented in Table 1).

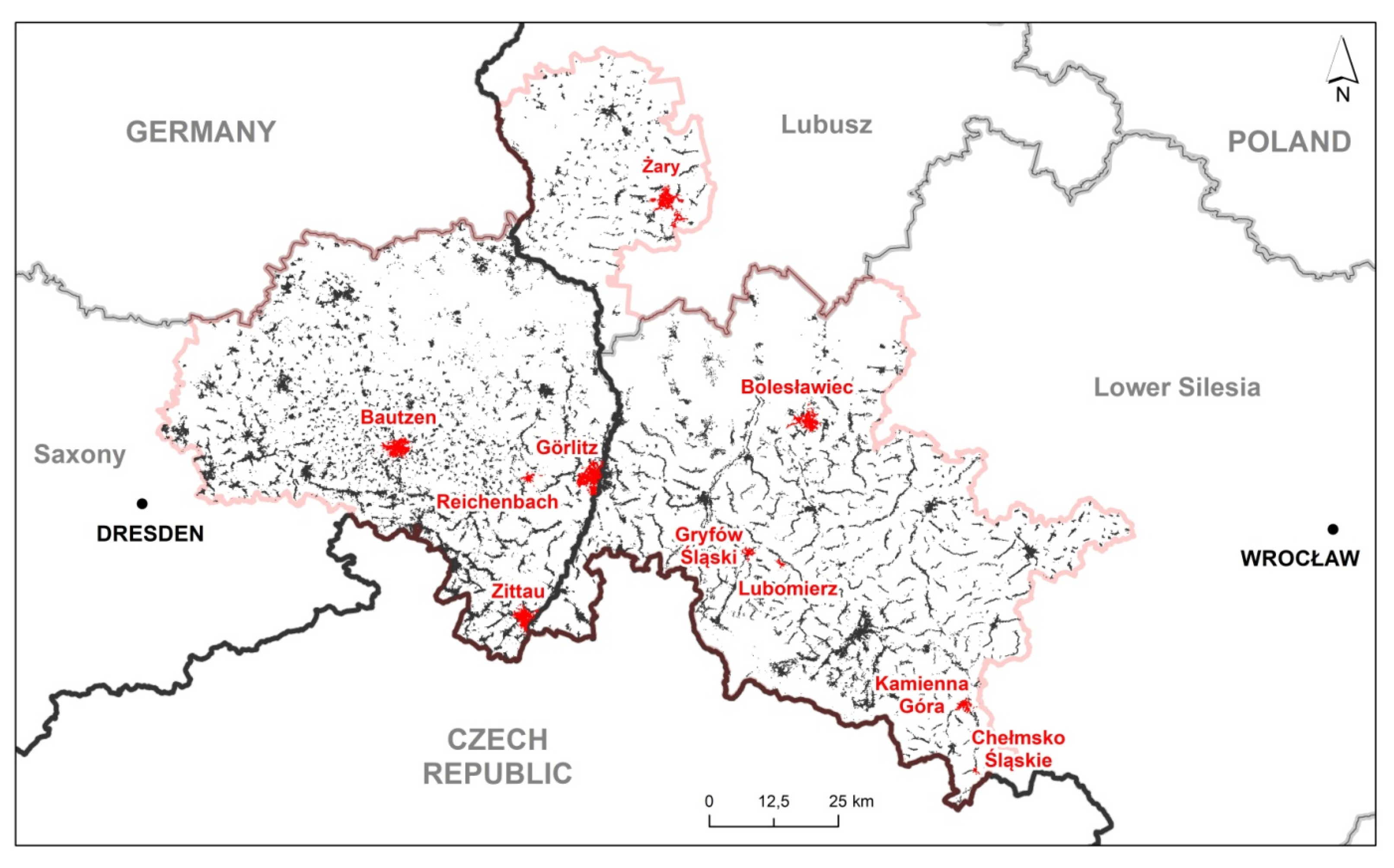

- The focus group discussion served as the platform for confirming or falsifying the assumptions elaborated previously. The assumptions were examined in 10 small and medium-sized towns on the Polish -German borderland. The pilot towns were the partner towns of the Polish-German project “REVIVAL!—Revitalization of Historic Towns in Lower Silesia and Saxony” implemented under the Interreg Poland-Saxony 2014–2020 cooperation programme: Bolesławiec, Chełmsko Śląskie (Chełmsko Śląskie lost its status as a town in 1945, after which it has been treated administratively as a village. However, because the settlement has retained its historic town centre with numerous elements of cultural heritage, the authors decided to include it in the study. In this article, the term “town” is used to refer to all 10 settlements, including Chełmsko Śląskie), Gryfów Śląski, Kamienna Góra, Lubomierz, and Żary in Poland; and Bautzen, Görlitz, Reichen-bach/O.L., and Zittau in Germany (Figure 1). All pilot towns possess a historic centre that is structurally distinct from other areas in terms of urban functions and fabric, in particular, an abundant CBH. All 10 towns are of medieval origin, having obtained their town charters in the 13th or 14th centuries. Of the six Polish towns, Żary belongs to the Lubusz Voivodeship, while the rest are located in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship. All four German towns are located in Saxony. According to data from 2019, the towns that could be classified as medium are: Görlitz (55,980 inhabitants), Bolesławiec (38,872), Bautzen (38,425), Żary (37,304), and Zittau (25,085). Only the small town of Kamienna Góra (18,840) has a population in the range of 10,000 to 20,000. The remaining towns have less than 10,000 inhabitants, including Gryfów Śląski (6617), Reichenbach/O.L. (4915), Chełmsko Śląskie (1936 (Data for Chełmsko Ślaskie from the PESEL registry)), and Lubomierz (2004) [77,78]. There is also great diversity in the area size of the settlements, ranging from 8 km2 to 67 km2, as well as in the size of their historic centres. From a regional and national perspective, most of the towns can be described as peripheral. Furthermore, they are also largely peripheral in socioeconomic terms. The meetings were held between October 2019 and January 2020 and were attended by representatives of the town administrations and societies of the partner towns. The composition varied and at times included mayors, elected town representatives, associations, traders, educational institutions, heritage conservation agencies, town managers, and planners, all of various age groups. The discussion focused on the links that exist between cultural heritage and local quality of life in these towns. Each of the five proposed dimensions was discussed along with its associated assumption. The selected results of the focus group discussions, along with literature references, are presented in Section 4.

4. Results

4.1. Inadequacy of Existing Indicators—Results from Literture Review

4.2. Cultural Built Heritage Matters—Results from the Focus Group Discussions

4.2.1. Urban Identity/Sense of Place

4.2.2. Society

4.2.3. Urban Fabric, Structure, and Space

4.2.4. Services and Facilities

4.2.5. Economy

4.3. Proposed Indicator-Based Approach

- −

- between cities of the same size, with and without a well-preserved CBH;

- −

- between cities of different sizes, both with a well-preserved CBH.

5. Conclusions and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Code | Study |

|---|---|

| S1 | ZDF Deutschland-Studie 2018 [ZDF Study on Germany 2018]. Available online: https://www.prognos.com/de/projekt/zdf-deutschland-studie-2018 (accessed on 24 November 2021) [61] |

| S2 | Bundeskanzleramt, Stab Politische Planung, Grundsatzfragen und Sonderaufgaben und Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, Leitungs- und Planungsabteilung. Bericht der Bundesregierung zur Lebensqualität in Deutschland [Report of the German Government on the Quality of Life in Germany]; Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [62] |

| S3 | Büttner, T.; Ebertz, A. Lebensqualität in den Regionen: Erste Ergebnisse für Deutschland [Quality of Life at the Regional Level: First Results for Germany]. ifo Schnelldienst 2007, 60, 13–19. [63] |

| S4 | Lemcke, J.; Zakrewski, T. Dresden in Zahlen [Dresden by Numbers]; Landeshauptstadt Dresden: Dresden, Germany, 2010. [64] |

| S5 | Hietzgern, K. Partizipation, Identifikation und Lebensqualität im städtischen Raum. Eine empirische Studie in der niederösterreichischen Stadt Krems [Participation, Identification, and Quality of Life in Urban Areas. Empirical Study in the Town of Krems in Lower-Austria] (MSc Thesis); Universität Wien: Vienna, Austria, 2009. [16] |

| S6 | Fachhochschule Westküste. Institut für Management und Tourismus (IMT). Tourismus und Lebensqualität in Cittaslow-Städten. Studienergebnisse in den Cittaslow-Städten Bad Essen, Deidesheim und Meldorf [Tourism and Quality of Life in Cittaslow-Cities. Study Results in the Cittaslow-Cities Bad Essen, Deidesheim and Meldorf]; Fachhochschule Westküste Institut für Management und Tourismus: Heide, Germany, 2018. [17] |

| S7 | Schmitz-Veltin, A.; West, C. Leben und Arbeiten in Penzberg: Studie zur Lebensqualität [Living and Working in Penzberg: Study on the Quality of Life]; Universität Mannheim: Mannheim, Germany, 2006 [18] |

| S8 | Heiden, A. Lebensqualität in Siegen. Eine Studie zum Stadterleben der Siegner Bürgerinnen und Bürger [Quality of Life in Siegen. A Study on Perceptions of the City Among the Citizens of Siegen]; Stadt Siegen: Siegen, Germany, 2009. [19] |

| S9 | iW Consult. Wirtschaftswoche Städteranking 2018 [Wirtschaftswoche’s Ranking of Cities 2018]. Available online: https://www.wiwo.de/politik/deutschland/staedteranking/definitionen/ (accessed on 24 November 2021). [65] |

| S10 | Sturm, G.; Walther, A. Landleben-Landlust? Wie Menschen in Kleinstädten und Landgemeinden über ihr Lebensumfeld urteilen [Country Life—Desire for the country? How People in Small Towns and Rural Communities Evaluate Their Living Environment], BBSR-Berichte KOMPAKT, 10/2010; Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung: Bonn, Germany 2010. [20] |

| S11 | Sturm, G., Walther, A. Lebensqualität in kleinen Städten und Landgemeinden: Aktuelle Befunde der BBSR-Umfrage [Quality of Life in Small Towns and Rural Communities: Current findings of the BBSR-Survey], BBSR-Berichte KOMPAKT, 5/2011; Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung: Bonn, Germany, 2011. [21] |

| S12 | European Commission. Quality of life in cities. Perception survey in 79 European cities; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2013. [66] |

| S13 | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Better Life Initiative Country Notes Germany. Available online https://www.oecd.org/statistics/Better-Life-Initiative-country-note-Germany.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2021). [67] |

| S14 | Istituto nazionale di statistica (Istat). Il benessere equo e sostenibile in Italia [Fair and Sustainable Wellbeing in Italy]; Istat: Roma, Italy, 2017. [68] |

| S15 | Grifoni, R.C.; D’Onofrio, R.; Sargolini, M. Quality of Life in Urban Landscapes: In Search of a Decision Support System. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [69] |

| S16 | Główny Urząd Statystyczny (GUS). Jakość życia w Polsce [Quality of Life in Poland]; Główny Urząd Statystyczny: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. [70] |

| S17 | Polityka. Ranking jakości życia [Quality of Life Ranking]. Available online: https://www.polityka.pl/tygodnikpolityka/mojemiasto/1762774,1,ranking-jakosci-zycia.read (accessed on 24 November 2021) [71] |

| S18 | Bański, J.; Pantyley, V. Warunki życia we wschodniej Polsce według regionów i kategorii jednostek osadniczych [Living Conditions in Eastern Poland by Region and Settlement Units]. Nierówności społeczne a wzrost gospodarczy 2013, 34, 107–123. [72] |

| S19 | Jeran, A. Jakość i warunki życia—perspektywa mieszkańców i statystyk opisujących miasta na przykładzie Bydgoszczy, Torunia i Włocławka [Quality And Conditions of Life—Perspective Residents and Statistics Describing the Town on the Example Bydgoszcz, Torun and Wloclawek]. Roczniki Ekonomiczne Kujawsko-Pomorskiej Szkoły Wyższej w Bydgoszczy 2015, 8, 222–235. [73] |

| S20 | PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). Raport na temat wielkich miast Polski [Report on the Great Cities of Poland]. Available online: https://www.pwc.pl/pl/sektor-publiczny/raporty_warszawa-pol.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2021). [74] |

| S21 | Binda, A.; Łobodzińska, A.; Motak, E.; Nowak-Olejnik, A.; Jarząbek, B.; Poniewierska, A. Miasta województwa małopolskiego: zmiany, wyzwania i perspektywy rozwoju [Cities of the Malopolska Region: Changes, Challenges and Development Perspectives]; Małopolskie Obserwatorium Rozwoju Regionalnego, Departament Polityki Regionalnej, Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Małopolskiego: Kraków, Poland, 2018. [75] |

| S22 | Konecka-Szydłowska, B. Ocena przestrzeni publicznej małych miast aglomeracji poznańskiej [Assessment of Public Spaces of Small Towns in the Poznań Agglomeration]. Problemy Rozwoju Miast 2016, 3, 5–12. [76] |

References

- Bogdański, M. Selected Factors Forming the Economic Base of Small And Medium-sized Towns in Poland. Samorz. Teryt. 2017, 3, 5–17. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Śleszyński, P. Poland of Medium-Sized Cities. Assumptions and the Concept of Deglomeration in Poland; Klub Jagielloński: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat (BMI). Discussion Forum on Spatial Development: Equal Living Conditions—Foundation for Homeland Strategies; MORO Informationen. 14/6; Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat: Berlin, Germany, 2019. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Inwestycji i Rozwoju. National Strategy of Regional Development 2030; Ministerstwo Inwestycji i Rozwoju: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Rozwoju. The Strategy for Responsible Development for the Period up to 2020 (Including the Perspective up to 2030); Ministerstwo Rozwoju: Warszawa, Poland, 2017. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Konecka-Szydłowska, B. Socio-Economic Links and Significance Of Small Towns of the Poznań Agglomeration. Studia Ekon. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Katowicach 2016, 279, 162–177. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Śleszyński, P. Determination and Typology of Medium-size Cities Losing Their Socio-Economic Functions. Prz. Geogr. 2017, 89, 565–593. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragila, M.; Leontidou, L.; Nuvolati, G.; Schweikart, J. Towards the development of quality of life indicators in the ‘digital’ city. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2004, 31, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borys, T. The Proposal of Seven Typologies of Life Quality. Pr. Nauk. Akad. Ekon. Wrocławiu Gospod. Sr. 2008, 9, 125–134. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Słaby, T. Standard of living, quality of life. Wiad. Stat. 1990, 6, 8–10. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, R.A. Objective and Subjective Quality of Life: An interactive Model. Soc. Indic. Res. 2000, 52, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E. Measuring Quality of Life: Economic, Social, and Subjective Indicators. Soc. Indic. Res. 1997, 40, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Better Life Index. Available online: https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/ (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Vemuri, A.W.; Costanza, R. The role of human, social, built, and natural capital in explaining life satisfaction at the country level: Toward a National Well-Being Index (NWI). Ecol. Econ. 2006, 58, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, K.; Badland, H.; Hooper, P.; Koohsari, M.J.; Mavoa, S.; Davern, M.; Roberts, R.; Goldfeld, S.; Giles-Corti, B. Developing Indicators of Public Open Space to Promote hHalth and Wellbeing in Communities. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 57, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hietzgern, K. Participation, Identification, and Quality of Life in Urban Areas. Empirical Study in the Town of Krems in Lower-Austria. Master’s Thesis, Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria, 2009. (In German). [Google Scholar]

- Fachhochschule Westküste. Institut für Management und Tourismus (IMT). Tourism and Quality of Life in Cittaslow-Cities. Study Results in the Cittaslow-Cities Bad Essen, Deidesheim and Meldorf; Fachhochschule Westküste Institut für Management und Tourismus: Heide, Germany, 2018. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz-Veltin, A.; West, C. Living and Working in Penzberg: Study on the Quality of Life; Universität Mannheim: Mannheim, Germany, 2006. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Heiden, A. Quality of Life in Siegen. A Study on Perceptions of the City Among the Citizens of Siegen; Stadt Siegen: Siegen, Germany, 2009. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Sturm, G.; Walther, A. Country Life—Desire for the country? How People in Small Towns and Rural Communities Evaluate Their Living Environment; BBSR-Berichte KOMPAKT, 10/2010; Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung: Bonn, Germany, 2010. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Sturm, G.; Walther, A. Quality of Life in Small Towns and Rural Communities: Current findings of the BBSR-Survey; BBSR-Berichte KOMPAKT, 5/2011; Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung: Bonn, Germany, 2011. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Battis-Schinker, E.; Al-Alawi, S.; Knippschild, R.; Gmur, K.; Książek, S.; Kukuła, M.; Belof, M. Towards Quality of Life Indicators for Historic Urban Landscapes—Insight Into a German-Polish Research Project. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2021, 10, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkoglu, H. Sustainable Development and Quality of Urban Life. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 202, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Roders, A.; van Oers, R. Editorial: Bridging Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 1, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, C.; Sutherland, M. Built Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Urban Development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmas, L.; Geronimi, V.; Noël, J.F.; Sang, J.T.K. Economic Evaluation of Urban Heritage: An Inclusive Approach Under a Sustainability Perspective. J. Cult. Herit. 2015, 16, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocca, F. The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development: Multidimensional Indicators as Decision-Making Tool. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthold, É.; Rajaonson, J.; Tanguay, G.A. Using Sustainability Indicators for Urban Heritage Management: A Review of 25 Case Studies. Int. J. Herit. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 4, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Appendino, F. Heritage-related Indicators for Urban Sustainable Development: A Systematic Review. Urban Transp. Constr. 2018, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, P.; Pereira Roders, A.R.; Colenbrander, B. Impacts of Common Urban Development Factors on Cultural Conservation in World Heritage Cities: An Indicators-Based Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Cultural Heritage: Report (Special Eurobarometer No. 466). Available online: https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/s2150_88_1_466_eng?locale=en (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- Runge, A.; Kwiatek-Sołtys, A. Small and Medium-Sized Polish Towns on the Settlement Continuum Axis. In Man in the Urban Space; Soja, M., Zborowski, A., Eds.; Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej UJ: Kraków, Poland, 2011; pp. 151–162. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- De Noronha, T.; Vaz, E. Theoretical Foundations in Support of Small and Medium Towns. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servillo, L.; Atkinson, R.; Hamdouch, A. Small and Medium-Sized Towns in Europe: Conceptual, Methodological and Policy Issues. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2017, 108, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runge, A. Methodological Problems Associated with Research on Midsize Towns in Poland. PR Geogr. 2012, 129, 83–101. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Poland. Basic Urban Statistics 2016; Statistics Poland, Statistical Office in Poznań: Warszawa, Poland; Poznań, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt-, und Raumforschung (BBSR). Continuous Urban Observation—Spatial Distinctions. Types of Cities and Counties in Germany. Available online: https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/DE/forschung/raumbeobachtung/Raumabgrenzungen/deutschland/gemeinden/StadtGemeindetyp/StadtGemeindetyp.html (accessed on 26 November 2021). (In German).

- Czapiewski, K.; Bański, J.; Górczyńska, M. The Impact of Location on the Role of Small Towns in Regional Development: Mazovia, Poland. Eur. Countrys 2016, 8, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffner, K. Small Towns in Development Rural Surroundings. In Small Towns in Local and Regional Development; Heffner., K., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2005; pp. 11–34. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, K. Small Towns and Rural Areas. Do Local Centers Are Needed by Contemporary Countryside? Studia Ekon. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Katowicach 2016, 279, 11–24. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, K.; Solga, B. Local Centres of Rural Areas Development—Significance and Connections of Small Towns. In The Role of Small Towns in the Development of Rural Areas; Rydz, E., Ed.; Studia Obszarów Wiejskich; PTG, IGiPZ PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2005; Volume 11, pp. 25–38. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatek-Sołtys, A. Small Towns in Lesser Poland Voivodship During Systemic Transformation; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Akademii Pedagogicznej: Kraków, Poland, 2004. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatek-Sołtys, A. Small Towns in Poland: Barriers and Factors of Growth. Procd. Soc. Behv. 2011, 19, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Porsche, L.; Steinführer, A.; Sondermann, M. (Eds.) Smalltown Research in Germany: State of the Art Perspectives, and Recommendations; Verlag der ARL—Akademie für Raumforschung und Landesplanung: Hannover, Germany, 2019. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Runge, A. The Role of Medium Towns in Development of a Settlement System in Poland; Uniwersytet Śląski: Katowice, Poland, 2013. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Lauber, B. (Ed.) Medium-Sized Town: Urban Life Beyond the Metropolis; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 2010. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Lauber, B. Other Urbanities: On the Plurality of the Urban; Böhlau Verlag: Vienna, Austria, 2018. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Steinführer, A. Villages and Small Towns in Transformation. Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung (bpb). 2020. Available online: https://www.bpb.de/izpb/laendliche-raeume-343/312690/doerfer-und-kleinstaedte-im-wandel (accessed on 26 November 2021). (In German).

- Śleszyński, P. Delimitation of Medium-Sized Towns Losing Socio-Economic Functions; IGiPZ PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2016. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, M.; Haase, A.; Leibert, T. Contextualizing Small Towns–Trends of Demographic Spatial Development in Germany 1961–2018. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B 2021, 103, 196–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuzańska-Żyśko, E. Small Towns in Transition: A Study in the Silesia Region; Wydawnictwo Śląsk: Katowice, Poland, 2005. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R. Policies for Small and Medium-Sized Towns: European, National and Local Approaches. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2017, 108, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Noronha, T.; Vaz, E. Framing Urban Habitats: The Small and Medium Towns in the Peripheries. Habitat Int. 2015, 45, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, H.; Motoyama, Y. Entrepreneurship in Small and Medium-Sized Towns. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2020, 32, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.P.; Serrano Giné, D.; Pérez Albert, M.Y.; Brandajs, F. Identifying and Classifying Small and Medium Sized Towns in Europe. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2017, 108, 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Growe, A. Research on Small and Medium-Sized Towns: Framing a New Field of Inquiry. World 2021, 2, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krätke, S. Strengthening the polycentric urban system in Europe: Conclusions from the ESDP. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2001, 9, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sýkora, L.; Mulíček, O. Territorial arrangements of small and medium-sized towns from a functional-spatial perspective. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2017, 108, 438–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, R. ‘Measure and mean‘—Middletown Revisited. In Medium-Sized Town: Urban Life Beyond the Metropolis; Schmidt-Lauber, B., Ed.; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 2010; pp. 38–51. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Czarnecki, A. Significance of Small Towns in the Structure of Economic Relations of Rural Enterprises in the Green Lungs of Poland Region. Studia Ekon. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Katowicach 2012, 92, 63–82. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- ZDF Deutschland-Studie 2018. Available online: https://www.prognos.com/de/projekt/zdf-deutschland-studie-2018 (accessed on 24 November 2021). (In German).

- Bundeskanzleramt, Stab Politische Planung, Grundsatzfragen und Sonderaufgaben und Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, Leitungs- und Planungsabteilung. Report of the German Government on the Guality of Life in Germany; Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung: Berlin, Germany, 2016. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Büttner, T.; Ebertz, A. Quality of Life at the Regional Level: First Results for Germany. IFO Schnelld. 2007, 60, 13–19. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Lemcke, J.; Zakrewski, T. Dresden by Numbers; Landeshauptstadt Dresden: Dresden, Germany, 2010. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- iW Consult. Wirtschaftswoche’s Ranking of Cities 2018. Available online: https://www.wiwo.de/politik/deutschland/staedteranking/definitionen/ (accessed on 24 November 2021). (In German).

- European Commission. Quality of Life in Cities. Perception Survey in 79 European Cities; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). OECD Better Life Initiative Country Notes Germany. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/statistics/Better-Life-Initiative-country-note-Germany.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Istituto nazionale di statistica (Istat). Fair and Sustainable Wellbeing in Italy; Istat: Roma, Italy, 2017. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Grifoni, R.C.; D’Onofrio, R.; Sargolini, M. Quality of Life in Urban Landscapes: In Search of a Decision Support System; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny (GUS). Quality of Life in Poland; Główny Urząd Statystyczny: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Polityka. Quality of Life Ranking. Available online: https://www.polityka.pl/tygodnikpolityka/mojemiasto/1762774,1,ranking-jakosci-zycia.read (accessed on 24 November 2021). (In Polish).

- Bański, J.; Pantyley, V. Living Conditions in Eastern Poland by Region and Settlement Units. Nierówności Społeczne Wzrost Gospod. 2013, 34, 107–123. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Jeran, A. Quality And Conditions of Life—Perspective Residents and Statistics Describing the Town on the Example Bydgoszcz, Torun and Wloclawek. Rocz. Ekon. Kuj.-Pomor. Szkoły Wyższej Bydg. 2015, 8, 222–235. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). Report on the Great Cities of Poland. Available online: https://www.pwc.pl/pl/sektor-publiczny/raporty_warszawa-pol.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2021). (In Polish).

- Binda, A.; Łobodzińska, A.; Motak, E.; Nowak-Olejnik, A.; Jarząbek, B.; Poniewierska, A. Cities of the Malopolska Region: Changes, Challenges and Development Perspectives; Małopolskie Obserwatorium Rozwoju Regionalnego, Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Małopolskiego: Kraków, Poland, 2018. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Konecka-Szydłowska, B. Assessment of Public Spaces of Small Towns in the Poznań Agglomeration. Probl. Rozw. Miast 2016, 3, 5–12. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Poland. Local Data Bank. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDL/dane/podgrup/temat (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Sachsen. Statistik. Available online: https://www.statistik.sachsen.de/html/bevoelkerungsstand-einwohner.html (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Heritage Lottery Fund. 20 Years in 12 Places: 20 Years of Lottery Funding for Heritage. Improving Heritage, Improving Places, Improving Lives. Report Summary. Heritage Lottery Fund. 2015. Available online: https://www.heritagefund.org.uk/sites/default/files/media/attachments/20_years_in_12_places_main_report.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Rochberg-Halton, E. The Meaning of Things. Domestic Symbols and the Self; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Murzyn-Kupisz, M. The socio-economic impact of built heritage projects conducted by private investors. J. Cult. Herit. 2013, 14, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, M.J. Interactional Past and Potential: The Social Construction of Place Attachment. Symb. Interact. 1998, 21, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujang, N.; Kozlowski, M.; Maulan, S. Linking Place Attachment and Social Interaction: Towards Meaningful Public Places. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2018, 11, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłosek-Kozłowska, D. Cultural Heritage and the Strategy of the Sustainable Development. Studia KPZK 2011, 142, 293–307. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Murzyn-Kupisz, M.; Działek, J. Cultural Heritage in Building and Enhancing Social Capital. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 3, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.E. City Size and Civic Involvement in Metropolitan America. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2000, 92, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannemann, C. Die The Development of Spatial Differentiations—Small Towns in Urban Research. In Varieties of the Urban; Löw, M., Ed.; Leske+Budrich: Opladen, Germany, 2002; pp. 265–279. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Golędzinowska, A. Transformation of Public Space in Medium Sized Town in Conditions of Market Economy in Poland. Ph.D. Thesis, Politechnika Gdańska, Gdańsk, Poland, 2015. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, C. The Medium-Sized Town—Ordinary Example or Ideal of Urban Development? In Medium-Sized Town: Urban Life Beyond the Metropolis; Schmidt-Lauber, B., Ed.; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt/Main, Germany, 2010; pp. 280–287. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Wuthnow, R. Small-Town America: Finding Community, Shaping the Future; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit (BMUB). Urban Monument Protection: Position Statement of the Expert Group 2015. The Heritage of the Cities—A Chance for the Future; Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit (BMUB): Berlin, Germany, 2015. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G.; Duif, L. Small Cities with Big Dreams: Creative Placemaking and Branding Strategies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, K. Downtown Development Principles for Small Cities. In Downtowns: Revitalizing the Centres of Small Urban Communities; Burayidi, M., Ed.; Garland: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puissant, S.; Lacour, C. Mid-sized French Cities and Their Niche Competitiveness. Cities 2011, 28, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, A. The Small Town on the Way to Modernity. Pro-Reg.-Online 2007, 4, 12–135. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Okulicz-Kozaryn, A. Unhappy Metropolis (When American City is Too Big). Cities 2017, 61, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallows, J.; Fallows, D. Why Young Americans Are Increasingly Moving to Small Towns? Time. 2018. Available online: https://time.com/5246798/american-small-towns-deborah-james-fallows/ (accessed on 28 November 2021).

- Farmer, L. Millennials Are Coming to America’s Small Towns. The Wall Street Journal. 2019. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/millennials-are-coming-to-americas-small-towns-11570832560 (accessed on 28 November 2019).

- Sullivan, B. Why Are Millennials Moving to These Small Towns? Credit.com. 2017. Available online: https://www.marketwatch.com/story/why-are-millennials-moving-to-these-small-towns-2017-10-30 (accessed on 28 November 2017).

- Knoop, B.; Battis-Schinker, E.; Knippschild, R.; Al-Alawi, S.; Książek, S. Built Cultural Heritage and Urban Quality of Life in a Context of Peripheralization: A Case Study from the German-Polish Border. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B, 2022; under review. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | Assumption |

|---|---|

| 1. Urban Identity/Sense of Place | The cultural built heritage makes the town special and provides a sense of home to its inhabitants. |

| 2. Society | The cultural built heritage of the town is a source of pride for the inhabitants, who together promote its preservation and use. |

| 3. Urban fabric, Structure, and Spaces | The historic centre plays a crucial role in the daily life of the inhabitants, hosting the most important administrative, social, cultural, religious, and commercial functions, as well as offering attractive housing, work, and public spaces. |

| 4. Services and Facilities | The cultural built heritage is widely used by all age groups for leisure, cultural, and educational activities; these are often related to local traditions and festivities. |

| 5. Economy | The cultural built heritage of the town is relevant to the local economy by offering job opportunities in the construction, tourism, and event sectors. It helps attract business and investment. |

| No. | Dimensions 1 | Name of Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 1 | • Satisfaction with the town (S4, S8, S10, S12, S17) 2 |

| 2. | 1 | • Social order: the feeling of being at home—sense of being lost (S22) |

| 3. | 1 | • Personal connection to the town (S5) |

| 4. | 1, 2 | • Local bonds to the place (relatives, friends, house, landscape) (S10) |

| 5. | 1, 2 | • Reputation of the neighbourhood (S10) |

| 6. | 1, 3 | • Image of the town/skyline (recognisability and symbolic value) (S6, S14) 3 |

| 7. | 1, 2, 3 | • Satisfaction with the nearby environment (S10) |

| 8. | 1, 2, 3 | • Satisfaction with the neighbourhood (S10) |

| 9. | 2 | • Number of local NGOs (S1, S7) |

| 10. | 2 | • Close/attractive/collaborative town for citizens (S6, S13) |

| 11. | 2 | • Forms of public participation (known, desired, used) (S8) |

| 12. | 2, 3, 4, 5 | • Perception of the town (S8) |

| 13. | 3 | • Mixture of commerce, recreational offerings and residential function (S11) |

| 14. | 3 | • Architectural quality and degree of maintenance of public areas in public housing (S14) |

| 15. | 3 | • Quality and level of maintenance of public-housing buildings (S14) |

| 16. | 3 | • Architectural quality (street furniture, art installations) of open spaces (S14) |

| 17. | 3 | • Adaptation of the type and architectural character of the building to the local climate (S14) |

| 18. | 3 | • Overall impact of colour and building harmony (materials, paving, openings, proportions) (S14) |

| 19. | 3 | • Urban and architectural form and arrangement: compact—dispersed; uniform—chaotic; existence of street furniture—lack of street furniture (S22) |

| 20. | 3 | • Functional order: good social infrastructure—lack of social infrastructure (S22) |

| 21. | 3 | • Aesthetic order: beautiful—unattractive (S22) |

| 22. | 3 | • Functional order: saturation with social infrastructure—lack of saturation with social infrastructure (S22) |

| 23. | 3 | • Satisfaction with the offer of goods in neighbourhood (S8) |

| 24. | 3 | • Distance to workplace in km (S10) |

| 25. | 3 | • Duration of commute to work (S10) |

| 26. | 3 | • Facilities within walking distance (S11) |

| 27. | 3, 5 | • Presence of shops (S4, S6, S12) |

| 28. | 3, 5 | • Local offers of food/clothing/household goods/other (city centre, district, other city, online) (S8, S11) |

| 29. | 3, 5 | • Density of bars and restaurants (S8, S11) |

| 30. | 4 | • Satisfaction with cultural organisations (S4, S6, S12) |

| 31. | 4 | • Number of museums (S7) |

| 32. | 4 | • Music events (S8) |

| 33. | 4 | • Markets, city fairs, and nightlife (S8) |

| 34. | 4 | • Local recreation possibilities (S11) |

| 35. | 4 | • Density and relevance of the museum heritage (museums, archaeological sites, monuments) (S14) |

| 36. | 5 | • Role of tourism in the city (S6) |

| 37. | 5 | • Influence of tourism on quality of life (profit for retailers, support of regional culture, more services offered) (S6) |

| Dimension | Name of Indicator | Type of Indicator | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The level of identification with the town | subjective | survey research |

| 1 | Sense of pride in the town | subjective | survey research |

| 1 | Visual attractiveness of the urban space | subjective | survey research |

| 1 | The level of uniqueness of the architectural cultural heritage of the town | subjective | survey research |

| 2 | Sense of local community | subjective | survey research |

| 2 | Opportunity to get involved in the local community life | subjective | survey research |

| 2 | Sense of having influence on the situation in the town | subjective | survey research |

| 2 | Number of institutions, organisations and associations related to the cultural heritage per 10,000 inhabitants | objective | municipal data, public statistics, field research, register of entrepreneurs |

| 3 | Land use mix of the town centre | objective | field research, spatial databases |

| 3 | Percentage of residential buildings in the town centre with retail and service facilities on the ground floor | objective | field research |

| 3 | Bicycle and pedestrian facilities in the town centre | objective | field research, spatial databases |

| 3 | Satisfaction with public spaces in the town centre | subjective | survey research |

| 4 | Satisfaction with the cultural offerings in the town | subjective | survey research |

| 4 | Number of cultural events that take place in the town centre during the year per 10,000 inhabitants | objective | municipal data, interviews with local stakeholders, public statistics |

| 4 | Participation of residents in cultural events taking place in the town centre | objective | survey research |

| 4 | Number of heritage/listed buildings used for cultural, social, or educational amenities | objective | municipal data, field research, spatial databases |

| 5 | Impact of cultural heritage on the economic development of the town | subjective | survey research |

| 5 | Number of enterprises based on local cultural heritage (tangible and intangible) per 10,000 inhabitants | objective | municipal data, field research, public statistics, register of entrepreneurs |

| 5 | Vacancy rate in the town centre | objective | field research, spatial databases |

| 5 | Number of tourists visiting the town per 10,000 inhabitants (annually) | objective | municipal data, public statistic |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Książek, S.; Belof, M.; Maleszka, W.; Gmur, K.; Kukuła, M.; Knippschild, R.; Battis-Schinker, E.; Knoop, B.; Al-Alawi, S. Using Indicators to Evaluate Cultural Heritage and the Quality of Life in Small and Medium-Sized Towns: The Study of 10 Towns from the Polish-German Borderland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031322

Książek S, Belof M, Maleszka W, Gmur K, Kukuła M, Knippschild R, Battis-Schinker E, Knoop B, Al-Alawi S. Using Indicators to Evaluate Cultural Heritage and the Quality of Life in Small and Medium-Sized Towns: The Study of 10 Towns from the Polish-German Borderland. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031322

Chicago/Turabian StyleKsiążek, Sławomir, Magdalena Belof, Wojciech Maleszka, Karolina Gmur, Marta Kukuła, Robert Knippschild, Eva Battis-Schinker, Bettina Knoop, and Sarah Al-Alawi. 2022. "Using Indicators to Evaluate Cultural Heritage and the Quality of Life in Small and Medium-Sized Towns: The Study of 10 Towns from the Polish-German Borderland" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031322

APA StyleKsiążek, S., Belof, M., Maleszka, W., Gmur, K., Kukuła, M., Knippschild, R., Battis-Schinker, E., Knoop, B., & Al-Alawi, S. (2022). Using Indicators to Evaluate Cultural Heritage and the Quality of Life in Small and Medium-Sized Towns: The Study of 10 Towns from the Polish-German Borderland. Sustainability, 14(3), 1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031322