Abstract

Martial arts (“budo”) is a service system in which instructors and students co-create physical and mental values through training encounters in a physical servicescape—the dojo. We explored how actors develop eudemonic wellbeing in this servicescape. We selected the dynamics theory of perception of servicescapes as the theoretical framework to examine the process of behavior change based on the interaction between participants and the environment. We also employed service-dominant logic (SDL), which views services as a value co-creation process among actors, and we also employed transformative service research (TSR), which explores uplifting change to improve wellbeing. We collected data from the World Seido Karate Organization Seido-juku, which has been active worldwide for more than 40 years. We conducted interviews with 17 members and analyzed the secondary data. The results indicated that (1) the participants integrated the value co-creation learned through the training at the servicescape as a model for daily life, and (2) the servicescape created positive mental change in the participants and promoted their personal growth. Martial arts training in a dojo can enable participants to independently create a state of wellbeing at any time. It supports sustainable personal growth, and the dojo is perceived as a eudemonic servicescape.

1. Introduction

Martial arts is a service system in which actors (instructors and students) co-create physical and mental values through training encounters in a physical servicescape—the dojo. Today, there are many students of martial arts worldwide. According to statistics from the Nippon Budokan Foundation (2016), more than 50 million people study martial arts overseas in nine martial arts disciplines. Martial arts are traditionally understood as “learning to treat people before learning to fight,” [1] and a “spiritual practice” [2] (p. 43). In the process of training, participants sometimes experience physical pain and setbacks, but they develop a sense of self-reliance as a mental strength [3,4] (p. 13). The service system of martial arts has unique characteristics that support the formation of eudemonic wellbeing [5], a state in which participants develop meaning and direction in their lives. However, not enough is known about how the actions and perceptions of the servicescape and actors—including institutions (such as normative consciousness) that comprise the service system—are linked to the value of martial arts practitioners.

Bitner et al. [6] define a servicescape as a space composed of physical and non-physical elements surrounding the service process. Participants engage in an act of meaning-making in the servicescape through their interactions in the service setting [7]. Rosenbaum [8] focuses on this action and develops a theory that participants form perceptions of the servicescape in stages. Servicescapes function as places where participants self-reflect and deepen their perceptions [9,10,11,12], thereby changing the meaning of the place and the methods of resource integration [13,14]. Although it is possible that these dynamics of actors’ perceptions function in the servicescape of the dojo—and that they influence the value co-creation of martial arts practitioners—these dynamics have been inadequately studied.

Rokeach (1973) [15] defines values as functionally integrated cognitive systems, beliefs about the desirability of a goal or action among several alternatives, and distinguishes between “terminal values,” which represent the desired ultimate state that humans seek, and “means values,” which represent the states necessary to reach a final value. The two values are “terminal value,” which indicates the ultimate state desired by humans, and “instrumental value,” which indicates the state necessary to reach the final value. However, there was no mention of the means of acquiring final value, necessary value, or the relationship between them [16]. In contrast, Schwartz & Bilsky (1987) [17] considered value to be the goal of individual behavior and an unwavering, consistent concept underlying behavior.

Research into the relationship between values and behavior has included the strength of predictors of values-based behaviors on wellbeing [18], changes in values through time [19], organizational sustainability and values [20], the role of values in influencing moral attitudes in sports [21], and the internalization of martial arts principles and philosophy and value systems [22]. However, there is not enough research on the mechanisms behind these—the value change process, and the organizations in which value co-creation is functioning and continuing—especially in the context of martial arts.

Service Dominant Logic (SDL) views service as a value co-creation process among actors. Participating actors create new exchangeable resources through resource integration [23,24] and contribute to the formation of their own wellbeing through interaction [25,26,27]. Transformative Service Research (TSR) explores the interaction between service actors and consumers to implement uplifting changes and improvements in the well-beinig of both parties [25,28]. Physical exercise contributes significantly to the development of positive psychological factors [29,30,31]. In the context of sports research, some pioneering studies have shown that sports improve well-beinig [32,33,34]. However, there is a paucity of research on the formation of well-beinig in martial arts [35]. Additionally, the research primarily focuses on professional competitive sports [36]. There is insufficient research on non-competitive or non-commercial martial arts.

Therefore, we focus on karate—one of the most popular martial arts among participants—and analyze how it is practiced as a service system that shapes wellbeing. We selected the qualitative Gioia research method [37,38,39] and the World Seido Karate Organization Seido-juku, which has been active globally for over 40 years. Seido-juku is an organization that has developed an independent philosophy and training system. It promotes the original, traditional budo, distinct from sport-oriented budo. This novel study analyzes the formation of wellbeing within a dojo from the viewpoint of budo as a service system.

1.1. Theoretical Background

1.1.1. Servicescape

Bitner et al. [6] define a servicescape as a space composed of physical and non-physical elements surrounding a service process. It has been reported that physical and social servicescapes influence co-creation value and customer satisfaction [40]. The physical environment influences human emotions and happiness [41]. For example, pleasant background music in a service space positively affects the attitudes of consumers and salespeople [42,43]. Additionally, service locations with well maintained plants, fountains, and walkways increase the level of individual and social wellbeing [44] while comfortable, attractive spaces enhance consumers’ willingness to purchase [45,46,47]. Intangible factors, such as the presence of other customers [48] or social interactions between customers and employees [49], affect how people feel in the service space.

Participants engage in an act of meaning making in the servicescape through their interactions in this setting [7]. Rosenbaum [8] focuses on this action and develops a theory of how participants’ perceptions of the servicescape are formed in stages. Participants continuously interact in the servicescape and perceive it multidimensionally as: (i) a practical space that satisfies their needs, (ii) a gathering space that satisfies their communication needs with their peers, and (iii) a home-like space that satisfies their need for personal and emotional support.

This act of signification is directed at the space, and towards oneself. Consumers internalize their interactions with a store’s environment and artifacts to form an identity [11,50,51,52,53,54,55]. For example, volunteers find their social roles through interactions in the servicescape, and this becomes a means of self-expression [56,57]. The servicescape functions as a place for participants to self-reflect and deepen their awareness [9,10,11,12].

Actors’ actions in the servicescape are influenced by the social institutions and norms they share [58,59,60,61], while simultaneously modifying them through social interaction [23,62,63,64,65,66]. For example, Ho & Shirahada [67] observed long-term participation for a shopping–assistance service for elderly people and found that the social exchange of this service in the servicescape forms altruistic norms out of contractual norms. This process also transforms each actor’s role perceptions. The continuous interaction among actors in the servicescape changes the meaning ascribed to the place and how the resources are integrated [13,14]. Furthermore, the interactions change the institutions within the servicescape. Actor dynamics are an important perspective in the effective analysis and description of the value co-creation process in the servicescape of the dojo.

1.1.2. Value Creation and Wellbeing

Rokeach (1973) states that values constitute a functionally integrated cognitive system and can be defined as beliefs about the desirability of an objective or action among several alternatives. There are central beliefs and the beliefs, attitudes, and values that are functionally formed around them. Values include personal values, which are an element of personality, and social values, which remain as social norms, behaviors, and institutions. Based on these hypotheses, two types of value were established: “terminal value,” which indicates the ultimate desirable state that humans seek, and “instrumental value,” which indicates the state necessary to reach the final value. However, the extent to which the factors of value set forth by Rokeach comprehensively and representatively covered the domain of values was rarely verified [16]. In contrast, Schwartz & Bilsky (1987), who considered the means of acquiring end values and relationships, considered value to be a goal of individual behavior as well as a consistent concept that underlies individual behavior in any given situation.

Although individuals with higher levels of mindfulness tend to be more aware of their internal experience and more attentive to their own behavior, values-based behavior is a stronger predictor for wellbeing than mindfulness [18]. Even after an event that temporarily alters values, the original values may continue to act to influence perceptions and behaviors as one’s normal life becomes longer and one no longer reflects on one’s values. There has been little systematic analysis on how values change over time and their underlying mechanisms [19]. In the context of organizations and values, the values that organizations proclaim and that guide the behavior and attitudes of their employees are widely shared and make a positive contribution to the socioeconomic environment, which is necessary to achieve organizational sustainability, and positive human potential is required as a precondition for this, but there have been few studies dealing with this [20]. The role of achievement motivation in determining behavior in sports is already well recognized, but the role of values, which seem to be an intervening variable influencing moral attitudes in sports, is still insufficient [21]. In martial arts, the internalization of their principles and philosophy is said to give moral values a fundamental place in the hierarchy of values, although it has been noted that instructors who teach the system of values have an important role in this [22]. However, there are few reported cases of organizations in which it works and continues to do so.

SDL views service as a value co-creation process among actors who create new, exchangeable resources through resource integration [23,24]. Kjellberg identifies these as generic actors [64]. Actors can create their wellbeing through their interactions [25,26,27]. Wellbeing is defined as a state of being happy, healthy, or prosperous (Merriam-Webster Dictionary). The study of wellbeing can be divided into: the hedonic stream, which measures wellbeing by emotions at the time of its realization, and the eudaimonia stream, which assesses the role of wellbeing in human development and social dynamics [68]. Aristotle says that “happiness (eudaimonia) is the highest human good that can be achieved through action and are self-sufficient and fulfilling” [69]. This is a concept of personal growth that explores the practice and purpose of human life [70,71,72].

Physical exercise contributes significantly to the development of positive psychological factors [29,30,31]. Research on the physical and mental benefits of exercise indicates that sports enhance self-esteem and disposition [73,74]. These positive experiences improve life balance and wellbeing [74,75,76]. Martial arts are beneficial to the body and mind and improve physical and mental reactions to success or failure [77], boost athletic performance [78], and enrich the development and education of young people [79]. Some pioneering studies have shown that psychosocial interventions through martial arts training in educational settings augment the self-discipline and wellbeing of young people [32,34]. However, the formation of wellbeing in the value creation process of martial arts has not been fully investigated [35].

1.1.3. Transformative Service Research

Transformative Service Research (TSR) is service research that explores the interaction between service actors and consumers to implement uplifting changes and improvements in the wellbeing of both parties [25,28]. TSR is unique because it defines the outputs of services as improving accessibility so that those in need can receive the services they need, mitigating vulnerability or the possibility of consumers being disadvantaged in some way, improving wellbeing and quality of life, maintaining equity, and reducing inequality.

Services include experiences that engender changes in the values and perceptions of the actors, which in turn trigger their motivation to engage in an activity [80]. From service work studies, Nasr et al. [81] and Nasr et al. [82] show that the experience of receiving positive feedback from customers has a constructive impact on service employees’ confidence and motivation. Moreover, Sharma et al. [83] show that organizational services positively impact employees physically, psychologically, and emotionally while heightening their performance and wellbeing.

TSR is unique because it views services as an opportunity to institute positive change through interactions in value co-creation with its participants. However, the TSR lens has not been fully applied to value co-creation situations other than commercial service. Sport has the potential to foster the formation of social identity [84] and form eudemonic wellbeing [33], and there is growing interest in providing support [85,86] and related services [86,87,88] to enhance the wellbeing of athletes, but the focus has been on professional competitive sports [36]. There is insufficient focus on the non-competitive aspects of martial arts as an inclusive sport.

1.2. This Study

The concept of a servicescape extends beyond a physical place where services are provided and functions as a space that influences the value co-creation process of service participants in various ways. We have shown that through value co-creation, service participants can satisfy their own needs and form wellbeing based on the experience of co-creation and relationship building among participants in the servicescape.

However, insufficient research has been conducted on the relationship between the servicescape and wellbeing formation. We selected martial arts as the focus of this study because it involves physical activity and character development. It is a process of self-discipline and growth in which a human being—through continuous practice, despite the experience of pain and setbacks—develops resilience. Martial arts philosophy is the practice of a normative system, the determination of a way of life, and the description of the internalization of certain values. Through the practice of martial arts, social interaction and social awareness can be enhanced. There is an expectation that martial arts, as a science that explores the human being, serves as an excellent approach to the realm of knowledge and scientific disciplines being described [89]. However, the process of how participants create wellbeing requires more attention.

In this qualitative study, we focus on karate, a martial art with numerous participants. Assuming that the karate dojo is a servicescape that forms wellbeing, we explore how dojos create wellbeing from the perspectives of the theory of perception—in which martial arts practitioners form meaning about the servicescape in stages—the formation of self-awareness through interaction among participants and the institutions that are formed in the servicescape.

2. Materials and Methods

Given the paucity of service-related research on martial arts and the limited understanding of the central concepts, we selected an exploratory research design. We analyzed qualitative data collected from interviews with karate practitioners and their responses to a questionnaire.

2.1. Target

The focus of this study is the World Seido Karate Organization Seido-juku (hereafter referred to as Seido-juku). Seido-juku is a school of karate founded in 1976 by Japanese karate master Kaicho (Grand Master/Chairman) Tadashi Nakamura. The headquarters are in New York, and there are 45 dojos in the United States and 109 dojos worldwide. Nakamura developed his philosophy on the principle of—“to walk the path of sincerity with honest people, cooperating and learning from each other, and never being ashamed as a human being” [90]. This is the foundation for the participants’ training in the dojos. Nakamura has created a training system that allows anyone to use karate as a medium for physical and mental growth.

We selected this school because it has produced numerous karate practitioners worldwide for about half a century, in different cultures and environments. Since Seido-juku continues to operate mainly as a dojo where individual participants gather for training, we decided to achieve our research objectives by investigating and analyzing the interactions that occur at the dojo—among multiple participants and their instructors—in terms of the theory of perception that forms meaning in stages for servicescapes, the formation of self-awareness among participants, and the institutions formed in the servicescape. This allows us to explore the social role of resource integration, value co-creation, and transformative value in the still insufficiently researched services of martial arts. Therefore, we selected an exploratory approach to gain a deeper understanding through in-depth research. Many members of Seido-juku have practiced for many years, even into old age. We assume that those members who had been practicing for many years and had been promoted to the instructor class or above are witnesses to the Seido-juku philosophy and the blossoming of their own lives. Therefore, by focusing on these individuals, we can examine and explain the multiple resources and dimensions of value that are integrated and bring Seido-juku into sharp relief. We conducted semi-structured interviews with three members living in Japan and administered a questionnaire similar to the questions asked in the semi-structured interviews to five members living in Japan and nine members living overseas. This allowed for the flexible discovery of information pertinent to each respondent. At this stage of data collection, we reached the point of data saturation—no new themes emerged from the data collected through the interviews and questionnaires.

The respondents from the interviews and questionnaires are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The respondents from the interviews and questionnaires.

2.2. Interview Protocol and Procedures

To achieve the research objective of exploring the formation of servicescapes through martial arts training, we asked the following research question: “What kind of servicescape exchanges take place in the dojo?” To obtain answers to this question, we selected one person from each of the different levels of training (instructor level, intermediate, and beginner) and asked the following questions in interviews: “What motivated you to take up karate?”, “What are your impressions of the karate dojo?”, “How do you perceive the training system?”, “What are your impressions of the competition among students in the dojo space?”, “What impact does karate have on your life?” “What memorable event impressed you with the Chairman?”. We asked students at the instructor level about their perceptions when teaching younger students. Because the interviews were semi-structured, the wording of the questions varied from interviewee to interviewee. Probe questions were used to further investigate the answers, and we used open-ended questions that emerged in the flow of the conversation to encourage deeper reflection and facilitate rich data collection. The interviews were conducted in a public café and lasted, on average, about one hour.

2.3. Analysis

We used the Gioia method to analyze our qualitative data. This grounded theory research method [91], which is robust and inductive, provides a theoretical concept of the social phenomenon being studied [37,38,39]. The advantages of the Gioia method are as follows. The Gioia method views both the informant and the researcher as “knowledgeable subjects” within a socially constructed world. The informant is assumed to be knowledgeable about their own intentions, thoughts, and feelings driving their actions [37]. The co-creation of a theory occurs when the knowledge of both parties is integrated into a resource [38,39].

In this method, the researcher first categorizes the data using the respondents’ statements as verbatim as possible. In context, the statements are then interpreted and structured. The statements are then substituted with theoretical terms from which an emergent, functional model arises [38,92].

This methodology can identify the interrelationships implied from the occurrence of a phenomenon while considering the mechanisms that led to the derived data structure [37,93].

The Gioia method begins with a primary analysis, in which terms articulated by informants are classified by comparing and highlighting their similarities and differences in determining the categories of the primary code [37,91]. In the secondary analysis, researcher-centered concepts, themes, and dimensions are established. Moving from primary codes to secondary themes and dimensions maintains the rigor of qualitative research and provides the basis for building the data structure [37]. An interpretive approach to the dynamic connections among the static concepts that emerge here—showing the relationships among them—facilitates the building of a dynamic, inductive model and an emergent grounded theory, rooted in the data [37,38,94]. Then, using the themes generated by the secondary analysis and the dimensions of the tertiary analysis, the data are modeled, accounting for the connections among concepts in an interpretive manner. Regarding the reliability and validity of the data analysis, we added that the two researchers who have promoted this study have discussed the results of the analysis together. This was performed to avoid biased interpretation by a single researcher [95].

3. Results

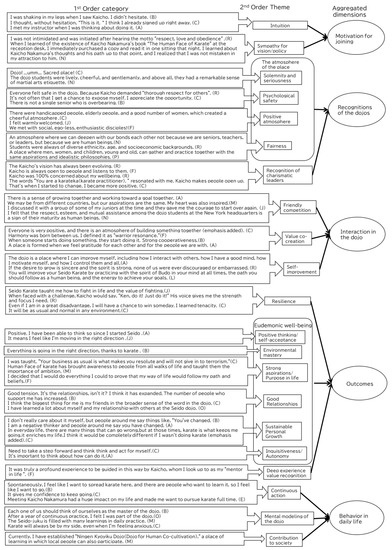

Figure 1 shows the structure of the analyzed data. The results of the analysis show that five different outcomes can be chronologically linked to the new outcomes achieved by the mutual activities of the participants in Seido-juku: 1. types of motivation for joining the dojo, 2. initial perceptions of the dojo, 3. types of interaction experienced through training with other participants in the dojo, 4. perceptions of the value of attending the dojo, and 5. changes in behavior in daily life attributed to practicing karate in the dojo.

Figure 1.

Data structure.

3.1. Motivation for Joining

Two themes were extracted as motivations for joining: intuition and sympathy for vision/policy. We found that the motivation of the participants of these dojos to join is diverse, suggesting that they can continue their training at Seido-juku, regardless of their reason for joining. The dojo was a space that fulfilled the needs of the participants when they joined the dojo and began their training.

3.1.1. Intuition

Respondents encountered karate either by chance—without any particular motivation—or when they went to see a friend participate in karate. We propose that the participants relied on intuition, rather than rationality, when they joined the dojo and that this was generated by observing training at the dojo:

When I was studying in New York, I did not look for something on my own, but there was a person named S. who wanted to do something... She looked at several places and found one that really impressed her. She felt this was a decent place... She was going to the same language school as me, so she asked me if I wanted to go there. That’s when I went to the trial session. (C).

I was only there as a chaperone when a work colleague asked me to go with her to see a karate class in Manhattan. In the end, my friend did not join but I did. Karate seemed like a good way to get in shape, and the people there were all very friendly. (K).

3.1.2. Sympathy for Vision/Policy

We also propose that empathy with the vision and policy of the Seido-juku motivates participants to join the dojo. L stated that he was in another school and had doubts about the dojo, was influenced by the vision and policies of the dojo and was impressed by the founder’s books. J’s decision to join Seido-juku was also influenced by the fact that she felt she could trust a dojo that had many long-time members:

I felt no purpose in life for karate, and I was questioning whether I would continue to practice karate. It was then that I came across Kaicho Nakamura’s book “The Human face of Karate”. I read the book in one sitting and was convinced that Seido Karate was the karate I was looking for. There was something that Kyokushinkai did not have. (L).

I wanted an instructor who continues to face the challenge of training students to become black belts and establishing them as senior karate practitioners. (J).

3.2. Perceptions of the Dojos

We extracted two themes for perceptions of the dojos: “Atmosphere of the place” and “Perceptions of a charismatic leader.” The results suggest that the respondents recognized the dojo as a place where they could continue their training in safety, where a leader is a person of character who could be respected, and where they could communicate with anyone without any division.

3.2.1. The Atmosphere of the Place

O from the UK described the dojo as a place where dojo students took their training seriously and where they felt a sense of holiness and solemnity that was different from their everyday lives (solemnity and seriousness). E from New Zealand stated that he was originally aware of the Chairman’s philosophy and recognized that the karate practiced at the dojo was safe and consistent with that philosophy. Specifically, he perceived that the dojo was a psychologically safe place where everyone was treated equally and could participate without physical or emotional danger (psychological safety). N, in Japan, remembers receiving polite explanations and responses from dojo participants as a memorable experience and attributed his decision to join and continue training to the welcoming atmosphere created by others (positive atmosphere). Furthermore, Japan’s Q perceived the dojo as a fair space where there were no prerequisites for learning karate and where students with handicaps could receive the assistance they need (fairness):

When I first visited the dojo, I was impressed. The pure energy and dedication of the students were breathtaking. The intricacies of the movements were unlike anything I had ever encountered before. I felt strongly that this was a place where I could learn and grow. The respect I had for the students and seniors in the dojo supported that attitude. (O).

We are very fortunate that Kaicho Nakamura has embodied his belief that the true form of karate is for all people to be able to practice safely. Kaicho Nakamura founded Seido-juku under the slogan of “The human face of karate”. He opened the door to karate for everyone, young and old, strong, and weak, able-bodied, and physically challenged. (E).

I immediately visited the dojo and took an introductory training session. I was impressed that a black-belt woman carefully guided me through the basics, basic self-defense, and Taikyoku kata, and that she even hung up the dustcloth after the practice, just like in Japan. (N).

At the Honbu (Headquarters) Dojo in New York, there were people from all walks of life practicing. There were elderly people, LGBTQ+ people, people with disabilities, and people like me from other countries. We practiced together every day without any distinction. The physically challenged were given the help they needed. A guide dog, waiting for its visually impaired owner, also watched the practice from its usual seat. Here, it was not only those who are strong and muscular and good at karate who were respected but also those who have various difficulties and came to train their bodies and minds. (Q).

3.2.2. Recognition of Charismatic Leaders

H, in the USA, suggested that the charisma of the founder, the instructor, ruled the place because of his outstanding technique and the instinctive presence that set them apart from other karate practitioners. L, of Japan, describes the founder as the most respected person for his karate strength and for his cultivated personality and his ability to act with unparalleled precision. This was based on:

I saw in him the mental focus and commitment of a warrior in action, a man who is committed to what he is doing... In addition to his natural athletic ability, strength, and agility, Kaicho Nakamura had a technique that could almost be described as artistic. Leadership is not about words, but about actions and attitude, and Nakamura had something more instinctive in addition to his looks... When I met Nakamura, I could tell by his movements that he was not like other karate practitioners... His voice, his demeanor, and his physical presence dominated the communication in the room. (H).

Kaicho Nakamura was my senior in Kyokushin Karate, and in addition to his strength in karate, he had a well-developed personality. He always thought about things in a human way and could take precise and unparalleled action based on that thinking. (L).

3.3. Interaction in the Dojo

We identified three themes for interaction in the dojo: friendly competition, value co-creation, and self-improvement. The participants explained that training is not something to be performed individually, but it is a friendly competition among peers. Further, as training continues, the perception of the dojo changes from a meaning of place to personal meaning and recognizes that it is a space for self-improvement. In the world of martial arts—which has a long tradition of preserving and passing on heritage—the systems are not rigid. Even the implicit distinctions among hierarchies and genders can be transformed through the co-creation of participants and instructors.

3.3.1. Friendly Competition

The participants reported that friendly competition means that fellow students encourage each other to improve their skills and virtues. In the dojo, each participant supports and encourages the goals of the other. When karate participation becomes infrequent, the participants hold each other accountable and create an environment of friendly competition among themselves. This is evident in the following comments from dojo participants:

One of the things I learned at Seido-juku was the importance of having a flexible and open mind without being bound by one set of values. There were people of all ages, genders, races, and occupations who came to practice at the dojo. It was a treasure of my life to be able to learn the Japanese martial art of karate while surrounded by such people. (N).

As time went on, many of us developed close relationships and were expected to attend classes and training. If we missed a day or two, we usually got a call. (D).

3.3.2. Value Co-Creation

The results suggest that in the dojo, there is value co-creation, which consists of collaboration among students and between instructors and students, and that students find new directions rather than adhering to tradition. The students experience creating something together with their peers, and even within the master–student relationship, there is mutual input and knowledge co-creation for the improvement of the dojo. J, in the USA, describes how the founder accepts the students’ suggestions to change old ways of doing things and create new ways:

All of my friends are positive, and we are all working together to create something... Yeah, there’s that kind of atmosphere. (C).

Kaicho wanted more female members in the dojo and wanted to make us feel welcome by making the training more inclusive... When I told him that I and the other women in the group felt more welcome if we were allowed to practice the same as the male students, he listened... Despite the traditional thinking that he took for granted, he went to his office and thought about what had happened and what the women wanted, and he decided that this was a time for change, a time to change his way of thinking. He listens and hears everyone. (J).

3.3.3. Self-Improvement

Self-improvement means learning deeply and growing spiritually. K, from the USA, stated that it was precisely because the dojo was a place of self-improvement—where one was constantly challenged to grow—that one could continue attending and practicing:

What keeps me coming to the dojo is that there is always a challenge worth tackling. Of course, my physical strength is declining, but in my training, I focus on the discipline that strengthens my inner self. That is most important to me. As long as I make that effort, the classes will always provide a learning experience. (K).

3.4. Outcomes

We identified resilience, eudemonic wellbeing, and deep experiential value recognition as outcomes that can be obtained through the interactions that occur during dojo practice. The results suggest that, by experiencing or acquiring these outcomes, the participants developed the ability to create a state of wellbeing, share it with their peers, contribute to their personal growth by changing their way of life, and influence the external environment.

3.4.1. Resilience

The analysis revealed that one of the outcomes developed was the spirit of never giving up—the ability to persevere, or resilience. E described this as a strong spirit; this is the spirit of living one’s life:

I define the role of Seido Karate as a martial art as follows: “To use the techniques and practice of Seido Karate as a tool and vehicle to bring out the spirit of living out one’s life as a human being,” “Let’s do it! I will be strong! I can do it!” It is important to persistently hold on to this attitude. A strong spirit is a strong life force, and it is the will to continue living and defending what we believe is right, no matter what. (E).

J describes this as the perseverance to resolve problems peacefully:

I confronted problems more directly and did not give up until they were resolved. I am more patient, more deliberate in my approach to people, and more willing to listen to them. If there is a conflict, I am more deeply and fully committed to resolving it peacefully. (J).

3.4.2. Eudemonic Wellbeing

Ryff identifies six dimensions of mental health (wellbeing), or wellness [5]. There are testimonies of people who have achieved these dimensions by continuing to practice at Seido-juku and simultaneously realizing eudemonic wellbeing [68]. This engenders positive consciousness. For example, Q, in Japan, learned to inspire herself and live cheerfully. She reported experiencing (1) self-acceptance. F, from Israel, suggested that he had become more positive in his thinking about realizing his dreams and visions, and achieved (2) environmental mastery, which is the ability to effectively manage people and the environment around him. P, from Japan, was determined to become an instructor by training at the dojo and to pass on what he had learned to future generations. Having such strong aspirations can be linked to the (3) creation of purpose in life. The interactions in the dojo are also thought to create (4) good relationships. For example, P from Japan was impressed by the greatness of the relationships created by the Seido family. K, from the USA, said that she learned a lot from training with friends worldwide, who respected their humanity. The dojo experience offers the possibility of sustainable (5) personal growth and (6) the acquisition of a spirit of inquiry and autonomy. For example, N, in Japan, discussed his personal growth, saying that he ran a dojo because he wanted to grow together with others. P, in Japan, discussed his inquisitiveness/autonomy, saying that he wanted to continue to practice so that he did not miss what was important, and so that his mind could be cultivated and bear fruit.

The beauty of diversity and the desire to coexist with others, knowing the suffering of others, brings joy to our lives by bonding us with people from all walks of life. I believe that learning how to encourage myself and have a cheerful attitude toward life has given me an irreplaceable asset. (Q).

A vision is also a dream. If you dream it, it will come true. When dreams come true, visions come true. (F).

It is not a gym for exercising, but a place to train the body and spirit. It is a place where men, women, and children, young and old, can gather and practice together with the same aspirations and ideal philosophy. It is also a place that gives us energy and heals us when we are tired. Such a place, exactly like the headquarters dojo in New York, is needed. I realized that maintaining and sustaining this place is my mission from now on. (P).

We, the karate practitioners of Seido, are scattered all over the world, connected by the bond of the World Seido Karate Organization. I am proud to have had the great opportunity to meet and train with so many good and decent people for so long. I have learned so much from them. I have great respect for their dedication and their humanity. (K).

Having friends from all over the world visit my dojo has broadened my worldview of myself and the members of the branch, who tend to have a narrow perspective. I am reminded of the grandeur and greatness of such a wonderful chain of human relationships spreading all over the world, and of the strong bonds of the Seido family. (P).

We are running the Tokyo Dojo with the sole intention of passing on to our dojo students all the techniques and spirit of “The Human Face of Karate” that we have learned from Kaicho Nakamura, and to improve ourselves together with our dojo students so that we can all grow as human beings. (N).

I will continue to keep my eyes open and ears attentive, so as not to miss what is really important, and I will continue to practice my mind with the “cultivate the mind and it will bear fruit” written by Kaicho Nakamura. (P).

3.4.3. Deep Experience Value Recognition

The interaction in the dojo of Seido-juku facilitates the acquisition and improvement of karate skills and the deep experience of value recognition—a transformation of personality with human growth that changes the way of thinking and living. For example, E, from New Zealand, spoke of growing a sense of spirituality, and K, from the USA, said that true karate—”The Human Face of Karate”—had a significant impact on her entire life. L, from Japan, said that training with people with physical disabilities allowed him to know their hearts:

With proper karate training, the limits of what you thought you knew are far away. Gradually, students will grow both physically and spiritually. Here is the most important point—they can grow their spiritual sense. In other words, martial arts prepare you to face the unknown enemies you will encounter in your life. (E).

I would like to thank Kaicho Tadashi Nakamura for creating a path for me to learn true karate. The curriculum created around the belief in the Human Face of Karate, the lessons learned, the opportunities for examination and growth for each of us, the people, and the organization created by them, have all had a profound impact on my wonderful life. (K).

I assisted classes for the mentally handicapped, the blind, and other physically handicapped people and trained with them. These people are learning the spirit of martial arts through Seido Karate and exercising their bodies, and they are using it as their life force. I was able to understand their feelings and hearts when I saw them learning with great effort. (L).

3.5. Behavior in Daily Life

We propose that training at the dojo of Seido-juku facilitated behavioral changes in daily life beyond the dojo setting. Specifically, we identified continuous action, mental modeling of the dojo, and social contribution. It is possible that the dojo itself—the space that generates wellbeing—is made conscious and becomes a eudemonic servicescape.

3.5.1. Continuous Action

The participants suggested that, in addition to improving their karate, what they gained from the practice inspired them to keep working toward their life goals. For example, Q, from Japan, stated that she was able to visualize what she wanted to become and to keep working toward that goal.

I believe that by looking within yourself to find out why you do karate and what it means for your life, you will find your true self, which in turn will lead you to know clearly what your wish is not only in karate but in life as well. I no longer give up as quickly in the face of difficulties, and I have a clear picture in my mind of what I want to become and how I want to live my life, and I can continue working toward that goal. (Q).

3.5.2. Mental Modeling of the Dojo

It is evident that through the accumulation of karate experience, some participants gained a sense that the dojo was an integral part of their daily way of life. The spirit of karate is usually shared by the participants in the dojo, and it dominates the servicescape as the norm for karate practice. Interestingly, however, the interview results suggest that this spirit, or mental model, may be a guiding principle in the participants’ daily life away from the dojo. For example, Q from Japan said that the “act of mutual understanding to know oneself and others” in the dojo functions outside of the dojo, and J from the USA said that her karate dojo training experience helped her to solve problems in her daily life. We theorize that the dojo is internalized by each individual as a mental model. Through training in the dojo, the philosophy and behavior of the dojo are incorporated into the students’ minds as concrete experiences. These are conceptualized as abstract concepts and become fixed in the student’s mind as new values. They begin to be used in daily life as beliefs. Through the accumulation of this series of actions, the consciousness formed in the dojo becomes the backbone of each individual’s daily life and becomes a mental model. Q expresses this concept as:

When you know yourself and can communicate your thoughts and feelings to others, they will open up to you and mutual understanding will deepen. This is very useful even outside of the dojo and is one of the ways I feel that karate has helped me in my life. (Q).

The hardest training always takes place outside the dojo. In the beginning, my mind was beating itself up in almost every sparring session. Now, when I am training with someone in the dojo, I can respond with focus and concentration to all of the real, present moments. However, when I leave the dojo, many things are not so easy. My mind goes back to the old days, flailing around in all directions like a big fish caught on a hook, looking for a way out. Seido karate practice is the strong fishing line I use over and over again to reel this fish in. This is the time to be thankful for the path of Seido and to be truly grateful to Kaicho for teaching me how to fight and the value of fighting in life. (J).

3.5.3. Contribution to Society

The interview results suggest that the karate experience—along with the aspect of mental modeling of the dojo that is reflected in the individual participants, may also motivate social contribution activities, such as community contribution and human resource development. For example, P, in Japan, considered promoting karate in school education for youth development; L, in Japan, took action to visit an elementary school affected by the earthquake and tsunami; and M, in Japan, said that his goal was to teach karate and develop human resources who can contribute to the world:

To spread the charm and splendor of karate to young people, we would like to assist and participate in clubs and club activities at the schools to which our members belong and at the schools from which they graduated. (P).

We visited S City at the request of Kaicho Nakamura and were shocked to see the devastation beyond our imagination. We gave donations from Seido-juku students around the world and the traditional Japanese paper cranes made to help people rise above the hardship to S City Hall and T Elementary School. We learned the importance of social contribution and felt the joy of helping and encouraging each other with the people around us. (L).

It is my mission and ambition that through Seido Karate, many people who can contribute to society, to their country, and the world will be trained in my dojo and that I will produce such people. (M).

4. Discussion

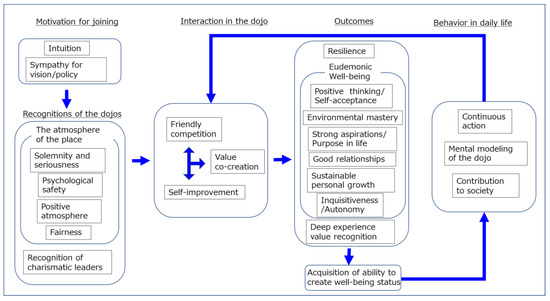

Figure 2 depicts the flow of wellbeing formation in a dojo based on the data that we organized and analyzed using the Gioia method.

Figure 2.

Flow of Wellbeing Formation in a dojo.

First, in the servicescape of the dojo, participants experience friendly competition, self-improvement, and value co-creation. This experience may be related to their perception of the dojo, including factors, such as the atmosphere of the dojo and the personalities of its leaders. The results suggest that these perceptions are nurtured through continuous involvement with the dojo.

The interactions of the participants in these dojos might have created a variety of wellbeing outputs, including their resilience, deep experiential value recognition, positive thinking/self-acceptance, environmental mastery, strong aspirations/life purpose, good relationships, sustainable personal growth, and inquisitiveness/autonomy. These outputs indicate the development of the ability to create a state of wellbeing, rather than the acquisition of a state of wellbeing. The exercise of this ability leads to changes in daily behavior, such as involvement with the dojo, continued effort toward achieving life goals, mental modeling of the dojo, and execution of social contributions.

The purpose of this study was to analyze how participants acquire eudaimonic wellbeing [5] by considering the dojo as a servicescape from the perspective of martial arts as a servicesystem. We believe that the martial arts service system has unique characteristics that support the formation of eudaimonic wellbeing, a state in which participants have a sense of meaning and direction in their lives. As a theoretical framework, we first selected the stage-based perception theory of servicescapes, which supports the process of behavior change based on the interaction between the participant and the environment. In addition, we utilized the analytical perspectives of Service Dominant Logic (SDL), which views services as a value co-creation process among actors, and Transformative Services Research (TSR), which explores uplifting change to improve wellbeing to examine the components of the service ecosystem, including value co-creation, institutions, and the environment. We developed an analytical framework that focuses on value co-creation and institutions, which are the components of service ecosystems, while utilizing the analytical perspectives of SDL and TSR.

There are two points that this study highlights as new possibilities for the function of servicescapes. First, the servicescape fosters a sense of integration with daily life. Second, the servicescape can facilitate uplifting mental changes in the participants and promote their personal growth.

Regarding the first point, the data from this study suggest that the dojo experience is remembered by the participants through training and examinations, following the philosophy and discipline of the dojo. This experience is then conceptualized through introspective observation and established as an authentic martial artist identity. This suggests that those who continue to participate in the dojo servicescape may gain psychological capital—defined by Luthans et al. [96] as hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism that promote positive reactions and autonomous goal achievement. They also use the martial artist identity gained in the dojo as a mirror for their lives. Servicescape research proposes that participants mature their perceptions of a place in stages and ultimately perceive it as a safe place, such as home [8]. Our study suggests that there is a new cognitive act of sense formation—that extends beyond the current recognition of place in a servicescape—and integrates a person’s values with the dojo. This sense is stored in the participant’s inner self through physical and mental training, and when taken out of the dojo and into everyday life, the servicescape is transferred as a mental model to various situations, becoming an independent ability to form wellbeing.

Second, we propose a perspective that explains how participants experience uplifting change. The physical activity of training in the servicescape of the dojo is not intended to be a transitory positive experience. Rather, what the participants specifically gain in the servicescape is human growth, such as a resilient spirit, and an altruistic attitude. The goal of the discipline is a positive transformation of the personality. The potential of sport and service to create transformative value has been recognized [85]. However, there is still insufficient research on how individuals experience uplifting change and how they form wellbeing through physical disciplines [11,14,97]. Our study suggests the following: participants face and harmonize with their true selves through the practice, thereby liberating the self that was previously limited. Then, the self turns outward and harmonizes with the surrounding organization and social and natural environment. In this process, participants positively transform their personalities—transformative values—while recognizing their sense of interconnectedness. They acquire the ability to support sustainable human growth, which enables them to face unknown difficulties in the future and to independently create a state of wellbeing at any time in their life path. An uplifting change and spiritual growth that improve wellbeing occur within the self [98] through the interaction among participants. Sustained practice is necessary to achieve this, but when participants achieve their goals, they become aware of new goals, which motivates them to maintain attendance at the dojo and continue practicing. A cycle of interaction occurs among participants. The participants in this study understand that training in the dojo is a process of human development and that the dojo continues to form various kinds of wellbeing through the repetition of training among participants. This finding adds new perspectives to transformative service research.

The wellbeing formation mechanisms examined in this paper have shown the potential for growth among participants, service builders, and providers, respectively. There have been many examples of transforming the operational policies and environment of physical places based on the concept of third places [99]. However, as we have shown in this paper, third place can also be considered as an opportunity to transform one’s way of life by moving from the perception of a physical place to absorbing the way the place itself interacts within the participants and transferring the interaction in the dojo in their daily lives. By utilizing this opportunity for participants to form the ability to acquire wellbeing through various activities in a third place, we can expect to create opportunities for the formation of wellbeing in various spaces beyond the physical third place, such as the metaverse and other virtual spaces.

In addition, with the growing interest in the SDGs (Social Development Goals), it is becoming increasingly important to create opportunities for people to grow through social contribution. Creating value for society through active participation in volunteer activities has the potential to provide growth and wellbeing to organizations, their members, and society. To this end, we believe that it is important to cultivate an awareness of the need for each individual to voluntarily tackle social issues. The model mechanism discussed in this study is expected to contribute as a tool for fostering human resources, which can innovate and provide new value to society. In particular, the mechanism demonstrated in this paper is relevant in that it is the result of wellbeing acquired through quality experiences in the servicescape, which matures the gaze towards others and results in altruistic behavior. We believe that this model can contribute to the study of human resource development that enables the autonomous formation of eudaimonia.

5. Conclusions

This study considered the dojo, a place of martial arts training, as a servicescape and aimed to conduct an exploratory analysis of how actors acquire eudaimonic wellbeing [5], a state of having meaning and direction in their lives. Our analysis suggested that the Seido-juku dojo is a servicescape where eudemonic wellbeing is realized through training. The participants in the study report that value co-creation in that place can be integrated as a model for daily life, and the effects contribute to human development as an uplifting change. This is not a transient positive experience, but the acquisition of the ability to develop a resilient spirit to live life, contribute socially, and behave altruistically. Participants can develop the ability to support sustainable human growth, using the training in the dojo as a medium to create an independent state of wellbeing at any time. Many service studies that involve physical activity, such as in the context of sports, discuss dominance in terms of competitiveness and commerciality, and martial arts are often discussed in this context. However, there is a paucity of research on how services are exchanged and how value co-creation occurs through martial arts, which are not necessarily competitive. By focusing on the dojo—where karate training has been sustained for more than 40 years—we propose that wellbeing can be developed through sustained involvement in its service activities. We believe that further research in the areas of sustainable human development, character building, and non-commercial activities—including the context of sports and martial arts—will further deepen the study of services to develop eudemonia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K. and K.S.; methodology, I.K. and K.S.; software, I.K.; validation, I.K. and K.S.; formal analysis, I.K. and K.S.; investigation, I.K.; resources, I.K. and K.S.; data curation, I.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K.; writing—review and editing, K.S.; visualization, I.K.; supervision, K.S.; project administration, K.S.; funding acquisition, K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number 20H01529), and The APC was waived.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barczynski, B.; Maciej Kalina, R. Budo-a Unique Keyword of Life Sciences. Arch. Budo 2009, 5, 117–119. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, S.; Brown, D. Kata-The True Essence of Budo Martial Arts? Rev. Artes Marciales Asiáticas 2016, 11, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauka, E.O. A Philosophical Examination of Karate’s Plausibility in Moral Education. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Res. 2018, 6, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, T. The Meaning and Role of Budo (the Martial Arts) in School Education in Japan. Arch. Budo 2006, 2, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J.; Crosby, L.; Brown, S.; Walker, B.; Kleine, S. Servicescapes: The Impact of Physical Surroundings on Customers and Employees. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, D.; Nilsson, E. All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Servicescape in Digital Service Space. J. Serv. Mark. 2017, 31, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S. Exploring the Social Supportive Role of Third Places in Consumers’ Lives. J. Serv. Res. 2006, 9, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuba, L.; Hummon, D.M. A Place to Call Home: Identification with Dwelling, Community, and Region. Sociol. Q. 1993, 34, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, Y.; Sirakaya-Turk, E.; Preciado, S. Symbolic Consumption of Tourism Destination Brands. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Massiah, C. An Expanded Servicescape Perspective. J. Serv. Manag. 2011, 22, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanasuwan, K. The Self and Sysbolic Consumption. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 2005, 6, 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, R. Existential Consumption and Irrational Desire. Eur. J. Mark. 1997, 31, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Kelleher, C.; Friman, M.; Kristensson, P.; Scherer, A. Re-Placing Place in Marketing: A Resource-Exchange Place Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 79, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, V.A.; Law, H.G. Structure of Human Values. Testing the Adequacy of the Rokeach Value Survey. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 49, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Bilsky, W. Toward A Universal Psychological Structure of Human Values. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, A.M.; Atkins, P.W.B.; Donald, J.N. The Meaning and Doing of Mindfulness: The Role of Values in the Link Between Mindfulness and Well-Being. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardi, A.; Goodwin, R. The Dual Route to Value Change: Individual Processes and Cultural Moderators. J. Cross. Cult. Psychol. 2011, 42, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farcane, N.; Deliu, D.; Bureană, E. A Corporate Case Study: The Application of Rokeach’s Value System to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Sustainability 2019, 11, 6612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Whitehead, J.; Ntoumanis, N. Relationships Among Values, Achievement Orientations, and Attitudes in Youth Sport. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2008, 30, 588–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostorz, K.; Gniezinska, A.; Nawrocka, M. The Hierarchy of Values vs. Self-Esteem of Persons Practising Martial Arts and Combat Sports. Ido Mov. Cult. 2017, 17, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. It’s All B2B...and beyond: Toward a Systems Perspective of the Market. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F.; Smith, R.H.; Hunt, S.; Laczniak, G.; Malter, A.; Morgan, F.; O’brien, M. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Ostrom, A.L.; Corus, C.; Fisk, R.P.; Gallan, A.S.; Giraldo, M.; Mende, M.; Mulder, M.; Rayburn, S.W.; Rosenbaum, M.S.; et al. Transformative Service Research: An Agenda for the Future. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.; Raggio, R.D.; Thompson, S.M. Service Network Value Co-Creation: Defining the Roles of the Generic Actor. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 56, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskela-Huotari, K.; Vargo, S.L. Institutions as Resource Context. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2016, 26, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Ostrom, A.L. Transformative Service Research: Advancing Our Knowledge About Service and Well-Being. J. Serv. Res. 2015, 18, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, D.L.; Hammond, E.J.; Reifsteck, C.M.; Williams, R.A.; Adams, M.M.; Lange, E.H.; Becofsky, K.; Rodriguez, E.; Shang, Y.-T. Physical Activity and Quality of Life. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2013, 46, S28–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive Psychology. An Introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuillemin, A.; Boini, S.; Bertrais, S.; Tessier, S.; Oppert, J.-M.; Hercberg, S.; Guillemin, F.; Brianc¸on, S. Leisure Time Physical Activity and Health-Related Quality of Life. Prev. Med. 2005, 41, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, G.; Fischetti, F.; Cataldi, S.; Latino, F. Effects of Shotokan Karate on Resilience to Bullying in Adolescents. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2019, 14, S896–S905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouali, D.; Hall, C.; Pope, P. Measuring Eudaimonic Wellbeing in Sport: Validation of the Eudaimonic Wellbeing in Sport Scale. Int. J. Wellbeing 2020, 10, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakes, K.D.; Hoyt, W.T. Promoting Self-Regulation through School-Based Martial Arts Training. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2004, 25, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macarie, I.-C.; Roberts, R. Martial Arts and Mental Health. Contemp. Psychother. 2010, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, S.; Diener, E. Goals, Culture, and Subjective Well-Being; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001; Volume 27, ISBN 0146167201. [Google Scholar]

- Gehman, J.; Glaser, V.L.; Eisenhardt, K.M.; Gioia, D.; Langley, A.; Corley, K.G. Finding Theory–Method Fit: A Comparison of Three Qualitative Approaches to Theory Building. J. Manag. Inq. 2018, 27, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, J.; Hassan, Y.; Pandey, J.; Pereira, V.; Behl, A.; Fischer, B.; Laker, B. Leader Signaled Knowledge Hiding and Erosion of Cocreated Value: Microfoundational Evidence From the Test Preparation Industry. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Halbusi, H.; Estevez, P.J.; Eleen, T.; Ramayah, T.; Hossain Uzir, M.U. The Roles of the Physical Environment, Social Servicescape, Co-Created Value, and Customer Satisfaction in Determining Tourists’ Citizenship Behavior: Malaysian Cultural and Creative Industries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Mehrabian, A. Evidence for a Three-Factor Theory of Emotions. J. Res. Pers. 1977, 11, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebat, J.C.; Chebat, C.G.; Vaillant, D. Environmental Background Music and In-Store Selling. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 54, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, L.; Morin, S. Background Music Pleasure and Store Evaluation: Intensity Effects and Psychological Mechanisms. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 54, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Ramirez, G.C.; Camino, J.R. A Dose of Nature and Shopping: The Restorative Potential of Biophilic Lifestyle Center Designs. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 40, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Grewal, D.; Parasuraman, A. The Influence of Store Environment on Quality Inferences and Store Image. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. Off. Publ. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1994, 22, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, B.; Bilgihan, A.; Haobin, B.; Buonincontri, P.; Okumus, F. The Impact of Servicescape on Hedonic Value and Behavioral Intentions: The Importance of Previous Experience. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 72, 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rayburn, S.W.; Voss, K.E. A Model of Consumer’s Retail Atmosphere Perceptions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L.; Kim, W.G. An Expanded Servicescape Framework as the Driver of Place Attachment and Word of Mouth. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 476–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A.; Tasci, A.D.A. Experienscape: Expanding the Concept of Servicescape with a Multi-Stakeholder and Multi-Disciplinary Approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruffe-Burton, H.; Wakenshaw, S. Revisiting Experiential Values of Shopping: Consumers’ Self and Identity. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2011, 29, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. Attachment to Possessions. In Place Attachment; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine, S.; Baker, S. An Integrative Review of Material Possession Attachment. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2004, 1, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Milligan, M.J. Interactional Past And Potential: The Social Construction Of Place Attachment. Symb. Interact. 1998, 21, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, M.J.; Collier, J.E. Experiential Purchase Quality: Exploring the Dimensions and Outcomes of Highly Memorable Experiential Purchases. J. Serv. Res. 2018, 21, 456–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. Changing Geographies of Care: Employing the Concept of Therapeutic Landscapes as a Framework in Examining Home Space. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 55, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.L.; Clark, M. Volunteer Choice of Nonprofit Organisation: An Integrated Framework. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 63–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymer, W.W.; Samu, S. Volunteer Service as Symbolic Consumption: Gender and Occupational Differences in Volunteering. J. Mark. Manag. 2002, 18, 971–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, J.; Koskela-Huotari, K.; Tronvoll, B.; Edvardsson, B.; Wetter-Edman, K. Service Ecosystem Design: Propositions, Process Model, and Future Research Agenda. J. Serv. Res. 2021, 24, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaka, M.A.; Vargo, S.L. Extending the Context of Service: From Encounters to Ecosystems. J. Serv. Mark. 2015, 29, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, S.; Patterson, A.; Maull, R.; Warnaby, G. Feed People First: A Service Ecosystem Perspective on Innovative Food Waste Reduction. J. Serv. Res. 2018, 21, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Institutions and Axioms: An Extension and Update of Service-Dominant Logic. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, M.E. Shared Intention. Ethics 1993, 104, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cova, B. Community and Consumption:Towards a Definition of the “Linking Value” of Product or s Ervices. Eur. J. Mark. 1997, 31, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellberg, H.; Nenonen, S.; Thomé, K.M. Analyzing Service Processes at the Micro Level: Actors and Practices. In The Sagehandbook of Service-Dominant Logic; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Storbacka, K.; Nenonen, S. Scripting Markets: From Value Propositions to Market Propositions. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taillard, M.; Peters, L.D.; Pels, J.; Mele, C. The Role of Shared Intentions in the Emergence of Service Ecosystems. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2972–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, B.Q.; Shirahada, K. Actor Transformation in Service: A Process Model for Vulnerable Consumers. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2021, 31, 534–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Mental Health in Adolescence: Is America’s Youth Flourishing? Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2006, 76, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, T. Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics, 2nd ed.; Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.: Indianapolis, CA, USA, 1999; ISBN 9781626239777. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Hedonia, Eudaimonia, and Well-Being: An Introduction. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B. Psychological Well-Being: Meaning, Measurement, and Implications for Psychotherapy Research. Psychother. Psychosom. 1996, 65, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H. Know Thyself and Become What You Are: A Eudaimonic Approach to Psychological Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratton, C. Sport, Health and Economic Benefit In Sport England; Sport England: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley, D.; Bickerton, C. Subjective Well-Being and Engagement in Arts, Culture and Sport. J. Cult. Econ. 2017, 41, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downward, P.; Rasciute, S. Does Sport Make You Happy? An Analysis of the Well-Being Derived from Sports Participation. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2011, 25, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, C. Well-Being in Competitive Sports-The Feel-Good Factor? A Review of Conceptual Considerations of Well-Being. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2011, 4, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, A. Coping with Competitive Situations in Humans. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005, 29, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, B.; Haijun, H.; Yong, L.; Chaohui, Z.; Xiaoyuan, Y.; Singh, M.F. Effects of Martial Arts on Health Status: A Systematic Review. J. Evid. Based. Med. 2010, 3, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, D.H.; Stout, J.R.; Burris, P.M.; Fukuda, R.S. Judo for Children and Adolescents: Benefits of Combat Sports. Strength Cond. J. 2011, 33, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press (OUP): New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, L.; Burton, J.; Gruber, T.; Kitshoff, J. Exploring the Impact of Customer Feedback on the Well-Being of Service Entities ATSR Perspective. J. Serv. Manag. 2014, 25, 531–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, L.; Burton, J.; Gruber, T. When Good News Is Bad News: The Negative Impact of Positive Customer Feedback on Front-Line Employee Well-Being. J. Serv. Mark. 2015, 29, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kong, T.T.C.; Kingshott, R.P.J. Internal Service Quality as a Driver of Employee Satisfaction, Commitment and Performance. J. Serv. Manag. 2016, 27, 773–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trussell, D.E. Building Inclusive Communities in Youth Sport for Lesbian-Parented Families. J. Sport Manag. 2020, 34, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinet, L.; Zhedanov, A. A “Missing” Family of Classical Orthogonal Polynomials. J. Sport Manag. 2010, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischman, D.; Sotiriadou, P.; Mulcahy, R.; Kean, B.; Cury, R.L. The Impact of “Capitalization” Social Support Services on Student-Athlete Well-Being. J. Serv. Mark. 2021; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, T.J.; Darcy, S.; Johns, R.; Pentifallo, C. Inclusive by Design: Transformative Services and Sport-Event Accessibility. Serv. Ind. J. 2016, 36, 532–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Sato, M.; Filo, K. Transformative Sport Service Research: Linking Sport Services with Well-Being. J. Sport Manag. 2020, 34, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cynarski, W.J.; Lee-Barron, J. Philosophies of Martial Arts and Their Pedagogical Consequences. Ido Mov. Cult. Martial Arts Anthropol. 2014, 14, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, T. The Human Face of Karate, 1st ed.; Shufunotomo CO., LTD.: Tokyo, Japan, 1989; ISBN 4-07-975055-2. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A. Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons, and Evaluative Criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, R.; Gioia, D.A. From Common to Uncommon Knowledge: Foundations of Firm-Specific Use of Knowledge as a Resource. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 421–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, K.G.; Gioiia, D.A. Building Theory About Theory Building: What Constitutes A Theoretical Contribution? Acad. Manaagement Rev. 2011, 36, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Chittipeddi, K. Sensemaking and Sensegiving in Strategic Change Initiation. Strateg. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirahada, K.; Wilson, A. Well-Being Creation by Senior Volunteers in a Service Provider Context. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2022; In press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Luthans, K.W.; Luthans, B.C. Positive Psychological Capital: Beyond Human and Social Capital. Bus. Horiz. 2004, 47, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Friman, M.; Ramirez, G.C.; Otterbring, T. Therapeutic Servicescapes: Restorative and Relational Resources in Service Settings. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Gupta, R.K.; Arora, A.P. Spiritual Climate of Business Organizations and Its Impact on Customers’ Experience. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, R.; Brissett, D. The Third Place. Qual. Sociol. 1982, 5, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).