Abstract

To enhance the sustainability of local communities in an aging society, older people have begun independently organizing community activities as social support services. The knowledge created by the community-dwelling older people for these community activities is a valuable resource. Although many studies have addressed the motivations of older people to participate in social activities, few studies have explored motivations toward knowledge creation in community activities. The present study investigates how older people are motivated knowledge creation in community activities from the perspective of services marketing. We conducted in-depth interviews with older individuals participating in community activities and identified four scenes (reminiscence, resonance, reuse, and rewarding) by content analysis. These four scenes are associated with specific contexts describing how older people are motivated knowledge creation in community activities. We interpreted these scenes from the axes of the source of motivation (intrinsic and extrinsic) and approaches for psychological well-being (affiliation and power) and developed the 4R model. Our findings add insights to services marketing to enhance the sustainability of local communities through community activities.

1. Introduction

As economies and health care have developed, the global population is aging. One in six people worldwide will be over 60 years old by 2030 [1], and it is estimated that the number of people aged 65 years and over will be more than double the number of children aged 12 years and under by 2050 [2]. In Japan, where the population is aging the fastest compared to the rest of the world, the percentage of people aged 65 years and over exceeded 29% in 2021 [3]. The aging population and urbanization have led to a decline in livelihoods in rural areas and weakened human connections in local communities [4,5]. Well-being has deteriorated as older people live in areas with feeble communities that face difficulties accessing essential services [6,7].

Since aging makes transportation over long distances difficult, relationships with neighbors are directly related to the well-being of community-dwelling older people [8]. In lonely older people, cognitive age increases and health deteriorates [9]. Aging makes it challenging to establish new relationships due to reduced perceptual and motor functions, so older people need support in building and maintaining relationships [10,11]. Their cognitive age and future time perspectives improve as they gain a positive outlook on their future, and their well-being increases as they can prevent the decline of physical functions compared to their chronological age [9,12]. Therefore, social support rooted in the local community is essential for enhancing the sustainability of rural areas in an aging society [13].

Despite the demand for support, aging and depopulation limited the management resources of local governments. Consequently, community-dwelling older people began independently managing service organizations to provide community activities as social support services [4,14]. Their community activities form servicescapes as a sub-community in the local community and encourage other community-dwelling older people to gather in those servicescapes [15,16]. Older people can age healthier by building positive relationships with other community residents [17]. Community-dwelling older people generate social benefits by engaging in community activities [18] and enhance their well-being by building supportive relationships with members involved in activities [19,20].

Knowledge creation by the activity members is essential to enhance the sustainability of local communities [21,22]. Due to the lack of management resources, community activities in an aging society require constant knowledge creation to overcome various constraints for sustainable social support services. Community activities increase participation by inviting friends through word of mouth rather than extensive advertising [23]. Knowledge creation is facilitated by widespread knowledge sharing through expanded organizational networks [24,25]. However, while many studies have examined the drivers of social participation among older people [26,27,28], how knowledge creation among the elderly is promoted in community activities has been overlooked. Uncovering older people’s motivations for knowledge creation can enhance the sustainability of local communities.

Community-dwelling older people participating in community activities are both consumers and providers of social support services [29,30]. They are both recipients of social support and actors providing support by integrating resources with other residents. By receiving social support, older people regain access to essential services and are empowered and participate in service delivery [14]. We draw on social identity theory and employee passion for investigating this duality. Social identity theory indicates that people seek their identity in the social community to which they belong [31]. Service consumer research shows that older people strongly tend toward this [32]. Moreover, community-dwelling older people participating in community activities may seek their identity in the sub-community formed by the participants of community activities [14,33]. This identification may strengthen older people’s attachment to community activities and motivate their knowledge creation for the sustainability of the activities. Employee passion describes the work attitudes of the frontline employees in terms of both affective and identity [34]. Frontline employees increase their passion through customer interaction [35], which is also aroused by developing job skills and providing high-quality services [34,36]. The arousal of passion may motivate knowledge creation for the service organization as older people will find it meaningful to participate in community activities. Services marketing research highlights the importance of understanding the interaction context to interpret the logic of actor behavior [37,38]. The service context is molded by relationships with other actors and affects the motivation of the behavior of the focal actor. Therefore, to understand older people’s motivation, unveiling how the context in community activities affects their knowledge creation from the perspectives of social identity theory and employee passion is necessary.

This study aims to investigate how older people are motivated knowledge creation in community activities from the perspective of services marketing. This study adds insights to services marketing for the sustainability of the local community through community activities. The structure of this study is as follows: Section 2 details the interview survey conducted for this study. Section 3 presents the 4R model as a theoretical model derived from the results. Finally, Section 4 concludes with theoretical and practical implications and future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

Data were collected through in-depth interviews. The respondents were 12 older individuals participating in three service organizations that provide community activities as social support services to enhance the sustainability of local communities with an aging population in Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan. Respondents were core members of the service organizations who were introduced by the executive of the organizations.

The first service organization, A, is a nonprofit organization (NPO) created by community-dwelling older people in a D Town, where more than 35% of the population is aged 65 years and over. They provide services to support the daily lives of older residents, focusing primarily on assisting with daily shopping. Since all stores have been closed due to urbanization, older people find it challenging to obtain groceries. As a result, older people in the town encounter “food deserts” [39]. NPO A began its activities by providing transportation support for older people to and from the supercenter. Later, they opened a store in the town to help with the daily shopping of older residents.

The second service organization, B, is a council founded by community-dwelling older people in an E Town and provides events to revitalize the town with the support of the local government. They represent a civic group collaborating directly with the government to revitalize the local community [40]. E Town has a history as a traditional pottery town. However, as in D Town, urbanization has not only decimated the commercial function of the town but also reduced interaction among the residents. By collaborating with the local government, some community-dwelling older people who had initially only gathered for their daily conversation organized Council B and utilized a vacant space as the town’s symbol to revitalize interaction among the residents.

The third service organization, C, is a committee organized by senior members of an agricultural cooperative in an F Town. They are engaged in the production of bamboo shoots and the protection of bamboo forests. The search for successors to the traditional bamboo shoots that have been produced for more than 100 years and branding of their products has revitalized human connections in the local community. Each interview took about one hour on average. Table 1 shows respondent demographics.

Table 1.

Respondent demographics.

The interview questions enquired about the knowledge the respondents had created in the community activities. Subsequently, to understand the context in which older people were motivated knowledge creation from the perspective of social identity theory, we asked what the community activities and service organizations meant to them. In addition, from the perspective of employee passion, we asked how the community activities and knowledge creation in those activities affected their passion.

Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Content analysis was used for analysis. First, the authors independently coded all the text data. The coding process consisted of open coding, in which each sentence was labeled with a category representing the meaning of its content, and axial coding, in which similar categories were integrated to elicit themes [41]. The themes were the data related to scenes of knowledge creation. Then, the authors arranged the relationships among the themes elicited in the coding process through discussion.

3. Results

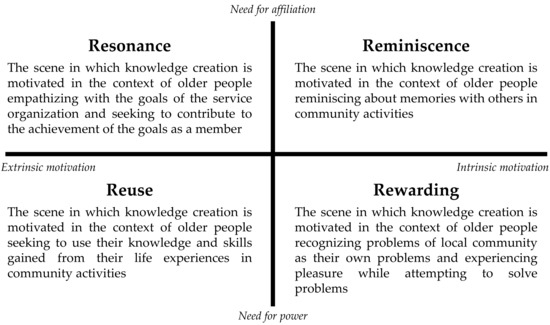

The interview data coding converged in four scenes in which older people are motivated knowledge creation as they work to solve their shared problems through community activities: Reminiscence, Resonance, Reuse, and Rewarding. The four scenes are each linked to a specific context that is classified according to two axes: source of motivation (intrinsic and extrinsic) and approaches for achieving psychological well-being (affiliation and power). The 4R model representing the relationship of four scenes is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

4R model.

Intrinsic motivation refers to behavior motivated by internal volition [42]. Conversely, behavior motivated based on external incentives is extrinsic motivation [43]. Older people are intrinsically motivated knowledge creation when they enjoy the content of community activities. Conversely, older people are extrinsically motivated knowledge creation when they feel compelled to engage in activities for a specific purpose or demand, such as to improve circumstances in their local community.

Psychological well-being is a state of possession of capability that contributes to positive functionings in life [44,45]. Psychological well-being is enhanced by acceptance of one’s life and building positive relationships with others [46,47]. We interpret the formation of psychological well-being from the perspective of the actions based on the need for affiliation and power. Actions based on the need for affiliation enable positive relationships with others by satisfying their demands [48,49]. In contrast, the action to dominate others by demonstrating one’s capabilities rather than developing relationships with others is based on the need for power [50,51]. In a scene in which older people seek to build positive relationships with others while inspiring each other in community activities, their knowledge creation can be interpreted based on the need for affiliation. Conversely, knowledge creation in a scene where older people want to change their surroundings by demonstrating their knowledge and skills can be understood as the need for power.

3.1. Reminiscence (Intrinsic Motivation/Need for Affiliation)

Reminiscence is a scene in which knowledge creation is motivated in the context of older people reminiscing about memories with others in community activities. Memories of the past are evoked through interaction, and knowledge is created because it is exciting to link these memories to current local community life. Therefore, reminiscence is based on intrinsic motivation and the need for affiliation. Recalling the past promotes older people’s service behavior [32]. Memory recall in reminiscence is evoked in conversation with other activity members. Such recollection triggers memories of others, and the successive recall of memories promotes knowledge creation among older people. An example of interview data are shown below.

I am 70 years old now, and I was born and raised here. Because I have spent so much of my life here, I remember how E Town used to be, and I also remember the buildings like this when I was a child. I want to talk about these things with people. When we made a map (of E Town as a community activity), we would get opinions like this place was not quite right. From such opinions, the conversation will gradually expand such as “Oh, there were people who lived here,” or “There was a store like this.”(Respondent 8)

In this example, Respondent 8 explains knowledge creation in a scene where people gathered to make a historical map of the town as an activity of Council B. Memories that an individual could not recall are brought back through discussion among participating members. He created knowledge that can be applied to the current environment by recalling the past environment of E Town through the development of a historical map. In this scene, Respondent 8 seems motivated knowledge creation about the activities that Council B should undertake to revitalize the town through the context of his reminiscing of memories.

3.2. Resonance (Extrinsic Motivation/Need for Affiliation)

Resonance is a scene in which knowledge creation is motivated in the context of older people empathizing with the goals of the service organization and seeking to contribute to the achievement of the goals as a member. Knowledge is created by empathizing with the service organization’s goal of solving community problems and building positive relationships with other residents while fulfilling their demands. Resonance is therefore based on extrinsic motivation and the need for affiliation. Strengthening resident networks can help older people understand their role in the community and encourage their engagement in community activities as social support services [52]. Examples of interview data are shown below.

If you want people to come shopping (in the store), it’s important to make it fun. If the products are the same every week, it will become boring, and people will dislike coming here. I’m trying to come up with ideas for new products, and I’m hoping that we can put something new on the shelves.(Respondent 3)

In this example, Respondent 3 explains knowledge creation in a scene where members of NPO A discussed products in the newly established store in D Town. She empathized with NPO A’s goal of helping older people in D Town access daily necessities. She believed that the products in the store should be designed to encourage older people to visit the store to achieve the service organization’s goal, and she generated ideas by guessing the needs of older residents. In this scene, Respondent 3 appears to be motivated knowledge creation about the products in the store through the context that resonates with service organization goals.

There is a family in my town with a 76-year-old woman with dementia and her 40 year old son who is mentally challenged. I’ve been inside (their house) sometimes and realized that it is very difficult for families with dementia patients. A comprehensive support network including the local government and care managers has been established, and we are working together now. If we had not provided such a comprehensive support system, the family would have been in trouble, and they would have died. But I’m proud that our efforts have made them live with a sense of fulfillment in their lives. …Well, there is also the garbage disposal problem. A large amount of garbage contains diapers and dirty things. But the son can hardly take the garbage out. I gathered various care staff to discuss countermeasures, and finally, it simply occurred to me to set up a basket of garbage stations in front of their house. And the city government approved this idea. This is the first case in the city. Thanks to that, the son, who hardly ever goes outside said he would. Positive thought has a positive result, leading to the son’s autonomous action. I’m proud of my proposal. I’m very impressed that I was able to kill two birds with one stone.(Respondent 2)

In this example, Respondent 2 explains knowledge creation in a scene where he gathered individuals caring for older people in D Town for a discussion. He empathized with NPO A’s goal of creating an environment where older residents can live comfortably. He wanted to help a family with a mother who has dementia and a mentally challenged son live a fulfilling life by solving their garbage disposal problem. In this scene, Respondent 2 appears motivated knowledge creation about solutions to the problem of garbage disposal for the family through the context that resonated with the goal of the service organization rather than from his interest.

3.3. Reuse (Extrinsic Motivation/Need for Power)

Reuse is a scene in which knowledge creation is motivated in the context of older people seeking to use their knowledge and skills gained from their life experiences in community activities. Knowledge is created by utilizing one’s knowledge and skills to solve local problems to gain a positive view of one’s life. Therefore, reuse is based on extrinsic motivation and the need for power. Reuse is similar to resonance in that it is rooted in the extrinsic motivation to solve local problems through community activities. However, reuse differs in that knowledge creation is motivated by the desire to enhance one’s psychological well-being through the application of one’s own knowledge and skills rather than considering others’ demands. Previous research indicates that self-efficacy facilitates knowledge creation from successful experiences among members of the younger generation [53]. In light of previous research, older people generally have richer knowledge and skills than younger generations, so their knowledge creation may be more easily motivated the reuse. Examples of interview data are shown below.

The best thing (for me in terms of the benefits of starting NPO A) was the prevention of dementia. I guess everyone is happy as a result. It’s a good thing, even for me. But, as far as what is most important for running a nonprofit organization, the most difficult thing is to collect money. This is impossible to manage unless you have studied marketing to some extent. Becoming a supporting member is a donation. That is to say, “Please give us money to do this kind of project and help this person.” There are not many people who can do this. I unintentionally have been in sales for 41 years. It’s a good thing I studied marketing. A long time ago, it was a matter of course that if you made a good product, people would buy it, but nowadays you need a contrivance. No matter how good the product is, everyone needs a contrivance. And if you couldn’t create a contrivance, you couldn’t sell the product. The wisdom (I gained in the past work) is still in use.(Respondent 1)

In this example, Respondent 1, the chairman of NPO A, explains knowledge creation in a scene where he applied the knowledge and skills he gained from his past work to the management of the NPO. He had been a manager in addition to a salesperson, and such experience with organizational management benefited him in knowledge creation regarding the service organization’s management. He was proud that he could use his unique knowledge and skills to manage the service organization, as few older people in rural areas have such extensive managerial experience. As an NPO, A sought a wide range of donors from all over the city to pay for their activities and needed to appeal to people with their activities. To create knowledge for this purpose, he reused the knowledge and skills he developed as a company employee to solve local problems. In addition, he affirmed his own life so far by using such knowledge and skills. In this scene, Respondent 1 appears motivated knowledge creation about NPO management through the context of reusing the knowledge and skills he developed as a company employee.

E Town is a town of Kutani (the traditional pottery of the city), so there are a lot of traditional Kutani works made by successive generals buried in each household. I thought it would be a good idea to bring them out. I hope we can discover some treasures. I hope to somehow bring out the treasures that are buried in the closets of each household so that everyone can see them. In G Town (another town in the same prefecture), people organize their back rooms for a festival, decorate their gardens, invite guests, and display their treasures on the porch. I saw it when I was young. I think it would be wonderful if we could have a festival by the townspeople, like a mini Kutani Festival. I think this idea would be useful.(Respondent 7)

In this example, Respondent 7 explains knowledge creation in a scene where he mentioned a festival as an activity he would like to undertake in B Council. He was looking for ideas to revitalize E Town and realized he could use his experience with a festival in another place and was thinking about how he could use that knowledge to promote interaction among residents in E Town. In this scene, Respondent 7 appears motivated knowledge creation about the concept of a festival in E Town by reusing past knowledge.

3.4. Rewarding (Intrinsic Motivation/Need for Power)

Rewarding is a scene in which knowledge creation is motivated in the context of older people recognizing problems of the local community as their problems and experiencing pleasure while attempting to solve problems. Knowledge is created by the pleasure of solving local community problems by applying one’s knowledge and skills in community activities. Therefore, rewarding is based on intrinsic motivation and the need for power. Knowledge creation is motivated by the participation of previously uninvolved older people in solving local community problems. They find pleasure and a sense of identity in the community by using their knowledge and skills [54]. An example of interview data are shown below.

I thought it would be more fun if we made our tea bowls at the last tea ceremony event. Along with it, participants brought their matcha bowls and asked the teacher to make tea for them to drink. The other day, we held a workshop for making matcha bowls, and we had a tea party with flowers. A thousand people came. It was a great success. I felt that we could do it. I felt confident that if we could continue this every year, we would be able to revitalize the whole town from the center of the building. Afterwards, many people who came to the workshop suggested that we install electricity and water. For example, we could hold a jazz party, or a science class for school children, or a pottery class. There are 13 rooms here. If we fix the light bulbs and the bad parts and rent the rooms, we can bring in money to pay the rent to the owner. We are trying our best to prepare a plan for this year and hope that the town and city will provide a budget for next year.(Respondent 8)

In this example, Respondent 8 explains knowledge creation in a scene where B Council members were discussing the renovation of a vacant former traditional Japanese-style restaurant building in E Town and its use as a symbol of the town. He was pleased with the event’s success after the renovation. He began to actively use his knowledge and skills in knowledge creation on the building’s use. In this scene, Respondent 8 seems motivated knowledge creation on how to use the building to promote interaction among community residents through the context of the community activities that he believed were worthwhile.

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

Our findings add insights regarding older people’s motivation toward knowledge creation in community activities that enhance the sustainability of local communities to services marketing. The knowledge of older people who participate in community activities is a valuable resource for enhancing the sustainability of local communities in an aging society. When their knowledge is utilized as management resources, engagement of the surrounding older people in community activities is promoted. As a result, local communities become more sustainable as service ecosystems [14,55]. From a services marketing perspective, we modeled the contexts in which older people are motivated knowledge creation through community activities. Contexts in which older people are motivated knowledge creation are categorized along two axes: source of motivation (intrinsic and extrinsic) and approaches for achieving psychological well-being (affiliation and power). Understanding their motivation in the context of community activities as social support services clarifies the logic of knowledge creation behavior. Moreover, it provides insight into the motivations of community-dwelling older people in accepting their role as part of the service ecosystem of the local community [56]. While some community-dwelling older people may be intrinsically motivated to participate in the service ecosystem as members of the local community based on the need for affiliation, others may engage in the service ecosystem as actors who contribute to sustaining the local community to satisfy extrinsic motivation and need for power. The present study underlines the importance of understanding the context of older people’s motivation as services marketing research. In addition, this study contributes to the theoretical development of the concept of context in service research by elucidating it from the perspective of motivation.

Increasing the sustainability of local communities through community activities improves the well-being of community-dwelling older people. Older people living in feeble communities in an aging society have limited access to essential services, which lowers their well-being [57,58]. As vulnerable consumers, even older people who do not have access to essential services can gain transformative value for enhancing well-being by participating in community activities [14,59]. Older people enhance their well-being by functioning not only as recipients of social support services but also as providers of them. As the 4R model indicates, community activities enable older people to fulfill their capabilities and lead vibrant lives. Performing a given task in community activities gives them new goals for their daily lives [60]. In addition, their well-being is enhanced through the productivity of knowledge creation while interacting with others [61]. The 4R model deepens our knowledge of the context in which community-dwelling older people are motivated knowledge creation in community activities as social support services and adds insights to transformative service research, which studies human well-being enhancement through services [62,63]

4.2. Practical Contributions

It is essential for service organizations that provide community activities to recognize the part of the 4R model to which their activities can be linked. Just as tailoring services to meet customers’ needs, providing activities with a context that meets the demands of older people who participate in community activities can facilitate their knowledge creation [64]. Community activities can meet the complex demands of participants themselves and as a servicescape where people gather [65]. A single community activity can have multiple contexts, as service is a sequential process shift from one scene to another. Individual older people may be simultaneously motivated knowledge creation by a single context, or a single older person may be motivated knowledge creation by multiple contexts. The synergistic effect may promote further knowledge creation among older people if it is motivated by multiple contexts.

Community activities provided by community-dwelling older people in rural areas need support for gathering participants continuously. Overcoming this problem requires increasing the engagement of a limited number of participants. This objective is achieved by clarifying the organization’s goals and providing internal marketing that shares these goals [66]. Being informed about the goals increases trust among organization members [67,68]. Reinforcing cooperation among participants in community activities promotes a spirit of mutual support [69] and can attract other older residents who may potentially become new participants. Service managers’ concern for activity members can reduce turnover and promote retention [70,71]. Since participants in community activities are both customers and providers, it is necessary to increase retention as providers and loyalty as customers [72]. Older people who provide community activities become sensors that identify the needs of recipients of benefits and highlight service organizations’ future goals by increasing retention and loyalty [73].

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

The present study investigated community-dwelling older people in Japan, where the population is aging. However, investigation of this issue in other cultures is required to verify the generality of the findings. The environment that older people face differs across cultures, and their behavior varies according to cultural differences [74,75]. Analyzing data from cultures other than Japan can provide a better understanding of the generality of the 4R model. Additionally, most respondents in this study were male. Gender differences exist in how people connect. These variations lead to differential health outcomes [76,77]. Investigating how gender differences arise in the impact of each context of the 4R model would be helpful in producing new insights. The present study is limited to qualitative analysis, and the proposed model requires verification of its generalizability. Therefore, a quantitative analysis should also be pursued in future studies. Revealing differences in the effects of motivation in each context is theoretically and practically significant. Furthermore, quantitative analysis is also valuable for clarifying multiple contexts’ synergistic effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Q.H. and K.S.; methodology, B.Q.H.; validation, K.S.; formal analysis, B.Q.H.; investigation, K.S.; resources, K.S.; data curation, B.Q.H.; writing—original draft preparation, B.Q.H.; writing—review and editing, K.S.; visualization, B.Q.H.; supervision, K.S.; project administration, K.S. and B.Q.H.; funding acquisition, B.Q.H. and K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS, grant numbers 21K13342 and 20H01529.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Bureau of Japan. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/data/topics/topi1291.html (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- Ho, B.Q.; Shirahada, K. Barriers to Elderly Consumers’ Use of Support Services: Community Support in Japan’s Super-Aged Society. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2020, 32, 242–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, F. China’s Carbon Inequality of Households: Perspectives of the Aging Society and Urban-Rural Gaps. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 185, 106449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boenigk, S.; Kreimer, A.A.; Becker, A.; Alkire, L.; Fisk, R.P.; Kabadayi, S. Transformative Service Initiatives: Enabling Access and Overcoming Barriers for People Experiencing Vulnerability. J. Serv. Res. 2021, 24, 542–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curb, J.D.; Guralnik, J.M.; LaCroix, A.Z.; Korper, S.P.; Deeg, D.; Miles, T.; White, L. Effective Aging Meeting the Challenge of Growing Older. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1990, 38, 827–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, Y.L.; Yen, I.H. Aging and Place: Neighborhoods and Health in a World Growing Older. J. Aging Health 2014, 26, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.R.; Slade, M.D.; Kasl, S.V. Longitudinal Benefit of Positive Self-Perceptions of Aging on Functional Health. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2002, 57, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudiny, K. ‘Active Ageing’: From Empty Rhetoric to Effective Policy Tool. Ageing Soc. 2013, 33, 1077–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattilo, J.; Lorek, A.E.; Mogle, J.; Sliwinski, M.; Freed, S.; Frysinger, M.; Schuckers, S. Perceptions of Leisure by Older Adults who Attend Senior Centers. Leis. Sci. 2015, 37, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppelwieser, V.G.; Klaus, P. Revisiting the Age Construct: Implications for Service Research. J. Serv. Res. 2021, 24, 372–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, N.; Akiyama, H. Japan: Super-Aging Society Preparing for the Future. Gerontologist 2011, 51, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, B.Q.; Shirahada, K. Actor Transformation in Service: A Process Model for Vulnerable Consumers. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2021, 31, 534–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish, J.T.; Berry, L.L.; Lam, S.Y. The Effect of the Servicescape on Service Workers. J. Serv. Res. 2008, 10, 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Simpson, P.M.; Siguaw, J.A. Communities as Nested Servicescapes. J. Serv. Res. 2017, 20, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, R.; Zaslavsky, O.; Cochrane, B.; Eagen, T.; Woods, N.F. Healthy Aging Through the Lens of Community-Based Practitioners: A Focus Group Study. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.; Singh, S.P.; Jyoti, J.; Pattanaik, F. Work Stress, Health and Wellbeing: Evidence from the Older Adults Labor Market in India. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2022, 9, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.L.; Smyer, M.A. The Resilience of Self-Esteem in Late Adulthood. J. Aging Health 2005, 17, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinstrup, J.; Meng, A.; Sundstrup, E.; Anderson, L.L. The Psychosocial Work Environment and Perceived Stress Among Seniors with Physically Demanding Jobs: The SeniorWorkingLife Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, B.Q.; Shirahada, K. Knowledge Co-Creation and Co-Created Value in the Service for the Elderly. Int. J. Knowl. Syst. Sci. 2016, 7, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Storey, C.; Kahn, K.B. The Role of Knowledge Management Strategies and Task Knowledge in Stimulating Service Innovation. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, D.; Tomczak, T.; Henkel, S. Can Friends Also Become Customers? The Impact of Employee Referral Programs on Referral Likelihood. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, B.Q.; Inoue, Y. Driving Network Externalities in Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijnen, M.; Lievens, A.; de Ruyter, K.; Wetzels, M. Knowledge Creation Through Mobile Social Networks and Its Impact on Intentions to Use Innovative Mobile Services. J. Serv. Res. 2009, 12, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Fombelle, P.W.; Bolton, R.N. Member Retention and Donations in Nonprofit Service Organizations: The Balance Between Peer and Organizational Identification. J. Serv. Res. 2021, 24, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katagiri, K.; Kim, J.H. Factors Determining the Social Participation of Older Adults: A Comparison Between Japan and Korea Using EASS. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194703. [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur, M.; Roy, M.; Michallet, B.; St-Hilaire, F.; Maltais, D.; Généreux, M. Associations Between Resilience, Community Belonging, and Social Participation Among Community-Dwelling Order Adults: Results from the Eastern Townships Population Health Survey. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 2422–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, B.Q.; Murae, Y.; Hara, T.; Okada, Y. Consumer Experience as Suppliers on Value Co-Creation Behavior. J. Serviceology 2019, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Murae, Y.; Ho, B.Q.; Hara, T.; Okada, Y. Two Aspects of Customer Participation Behaviors and Different Effects in Service Delivery: Evidence from Home Delivery Services. J. Mark. Dev. Comp. 2019, 13, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Worchel, S., Austin, W.G., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Grougiou, V.; Pettigrew, S. Senior Customers’ Service Encounter Preferences. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Ward, J.; Walker, B.A.; Ostrom, A.L. A Cup of Coffee with a Dash of Love: An Investigation of Commercial Social Support and Third-Place Attachment. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 10, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A.C.; Newmeyer, C.E.; Jung, J.H.; Arnold, T.J. Frontline Employee Passion: A Multistudy Conceptualization and Scale Development. J. Serv. Res. 2022, 25, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, J.M.; Ho, V.T.; O’Boyle, E.H.; Kirkman, B.L. Passion at Work: A Meta-Analysis of Individual Work Outcomes. J. Organ. Behav. 2020, 41, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; Wheeler, J.K.; Cox, J.F. A Passion for Service: Using Content Analysis to Explicate Service Climate Themes. J. Appl. Psychol. 1992, 77, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbert, S.; Winklhofer, H.; Temerak, M.S. Customers as Resource Integrators: Toward a Model of Customer Learning. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 15, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Institutions and Axioms: An Extension and Update of Service-Dominant Logic. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, S.; Macintyre, S. “Food Deserts”: Evidence and Assumption in Health Policy Making. BMJ 2002, 325, 436–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.P. Service Provision Through Public-Private Partnerships: An Ethnography of Service Delivery to Homeless Teenagers. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies of Qualitative Research; Weidenfeld and Nicholson: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L. Mental Health in Adolescence: Is America’s Youth Flourishing? Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2006, 76, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H. Know Thyself and Become What You Are: A Eudaimonic Approach to Psychological Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H. Psychological Well-Being: Meaning, Measurement, and Implications for Psychotherapy Research. Psychother. Psychosom. 1996, 65, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.W. Motives in Fantasy, Action, and Society; Van Nostrand: Jersey City, NJ, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, H.A. Explorations in Personality; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, D.C. The Achieving Society; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, D.C. Human Motivation; Scott Foresman: Chicago, IL, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Verleye, K.; Gemmel, P.; Rangarajan, D. Managing Engagement Behaviors in a Network of Customers and Stakeholders: Evidence from the Nursing Home Sector. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, B.Q. Effects of Learning Process and Self-Efficacy in Real-World Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattilo, J.; Mogle, J.; Lorek, A.E.; Freed, S.; Frysinger, M. Using Self-Determination Theory to Understand Challenges to Aging, Adaptation, and Leisure Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Act. Adapt. Aging 2018, 42, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Fehrer, J.A.; Jaakkola, E.; Conduit, J. Actor Engagement in Network: Defining the Conceptual Domain. J. Serv. Res. 2019, 22, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danatzis, I.; Karpen, I.O.; Kleinaltenkamp, M. Actor Ecosystem Readiness: Understanding the Nature and Role of Human Abilities and Motivation in a Service Ecosystem. J. Serv. Res. 2022, 25, 260–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemot, S.; Dyen, M.; Tamaro, A. Vital Service Captivity: Coping Strategies and Identity Negotiation. J. Serv. Res. 2022, 25, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, B.; Hurmerinta, L.; Leino, H.M.; Menzfeld, M. Autonomy or Security? Core Value Trade-Offs and Spillovers in Servicescapes for Vulnerable Consumers. J. Serv. Res. 2022, 25, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieler, M.; Maas, P.; Fischer, L.; Rietmann, N. Enabling Cocreation with Transformative Interventions: An Interdisciplinary Conceptualization of Consumer Boosting. J. Serv. Res. 2022, 25, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.L.; Sarkisian, N.; Winner, E. Flow and Happiness in Later Life: An Investigation into the Role of Daily and Weekly Flow Experiences. J. Happiness Stud. 2009, 10, 703–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeilig, H.; Tischler, V.; van der Byl Williams, M.; West, J.; Strohmaier, S. Co-Creativity, Well-Being and Agency: A Case Study Analysis of a Co-Creative Arts Group for People with Dementia. J. Aging Stud. 2019, 49, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Ostrom, A.L.; Corus, C.; Fisk, R.P.; Gallan, A.S.; Giraldo, M.; Mende, M.; Mulder, M.; Rayburn, S.W.; Rosenbaum, M.S.; et al. Transformative Service Research: An Agenda for the Future. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Gremler, D.D.; Kumar, S.; Pattnaik, D. Mapping of Journal of Service Research Themes: A 22-Years Review. J. Serv. Res. 2022, 25, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sok, P.; Sok, K.M.; Danaher, T.S.; Danaher, P.J. The Complementarity of Frontline Service Employee Creativity and Attention to Detail in Service Delivery. J. Serv. Res. 2018, 21, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimoun, L.; Gruen, A. Customer Work Practices and the Productive Third Place. J. Serv. Res. 2021, 24, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, P.K.; Ungson, G.R. Internal Market Structures: Substitutes for Hierarchies. J. Serv. Res. 2001, 3, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisingerich, A.B.; Bell, S.J. Perceived Service Quality and Customer Trust: Does Enhancing Customers’ Service Knowledge Matter? J. Serv. Res. 2008, 10, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H.; Sandvik, K.; Selnes, F. Direct and Indirect Effects of Commitment to a Service Employee on the Intention to Stay. J. Serv. Res. 2003, 5, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.I.; Lee, I.C.; Chu, T.L.; Chang, H.T.; Liu, T.W. How Can Supervisors Improve Employees’ Intention to Help Colleagues? Perspectives from Social Exchange and Appraisal-Coping Theories. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 15, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, A.; Babakus, E.; Yavas, U. The Effects of Perceived Management Concern for Frontline Employees and Customers on Turnover Intentions: Moderating Role of Employment Status. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 9, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, R.V.; Bayón, T.; Totzek, D. How Customer Satisfaction Affects Employee Satisfaction and Retention in a Professional Service Context. J. Serv. Res. 2013, 16, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D. Understanding Relationship Marketing Outcomes: An Integration of Relational Benefits and Relationship Quality. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; Paul, M.C.; White, S.S. Too Much of a Good Thing: A Multiple-Constituency Perspective on Service Organization Effectiveness. J. Serv. Res. 1998, 1, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, M.S.; Fiske, S.T. Modern Attitudes Toward Older Adults in the Aging World: A Cross-Cultural Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 993–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirahada, K.; Ho, B.Q.; Wilson, A. Online Public Services Usage and the Elderly: Assessing Determinants of Technology Readiness in Japan and the UK. Technol. Soc. 2019, 58, 101115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.N.; Waters, D.L.; Gallagher, D.; Morley, J.E.; Garry, P. Predictors of Skeletal Muscle Mass in Elderly Men and Women. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1999, 107, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicotte, M.; Alvarado, B.E.; León, E.M.; Zunzunegui, M.V. Social Networks and Depressive Symptoms Among Elderly Women and Men in Havana, Cuba. Aging Ment. Health 2008, 12, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).