Natural Environment Protection Strategies and Green Management Style: Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Literature Review Results

3.1. SLR Results

3.2. CLR Results

3.2.1. Green Management Style

3.2.2. Natural Environment Protection Strategies

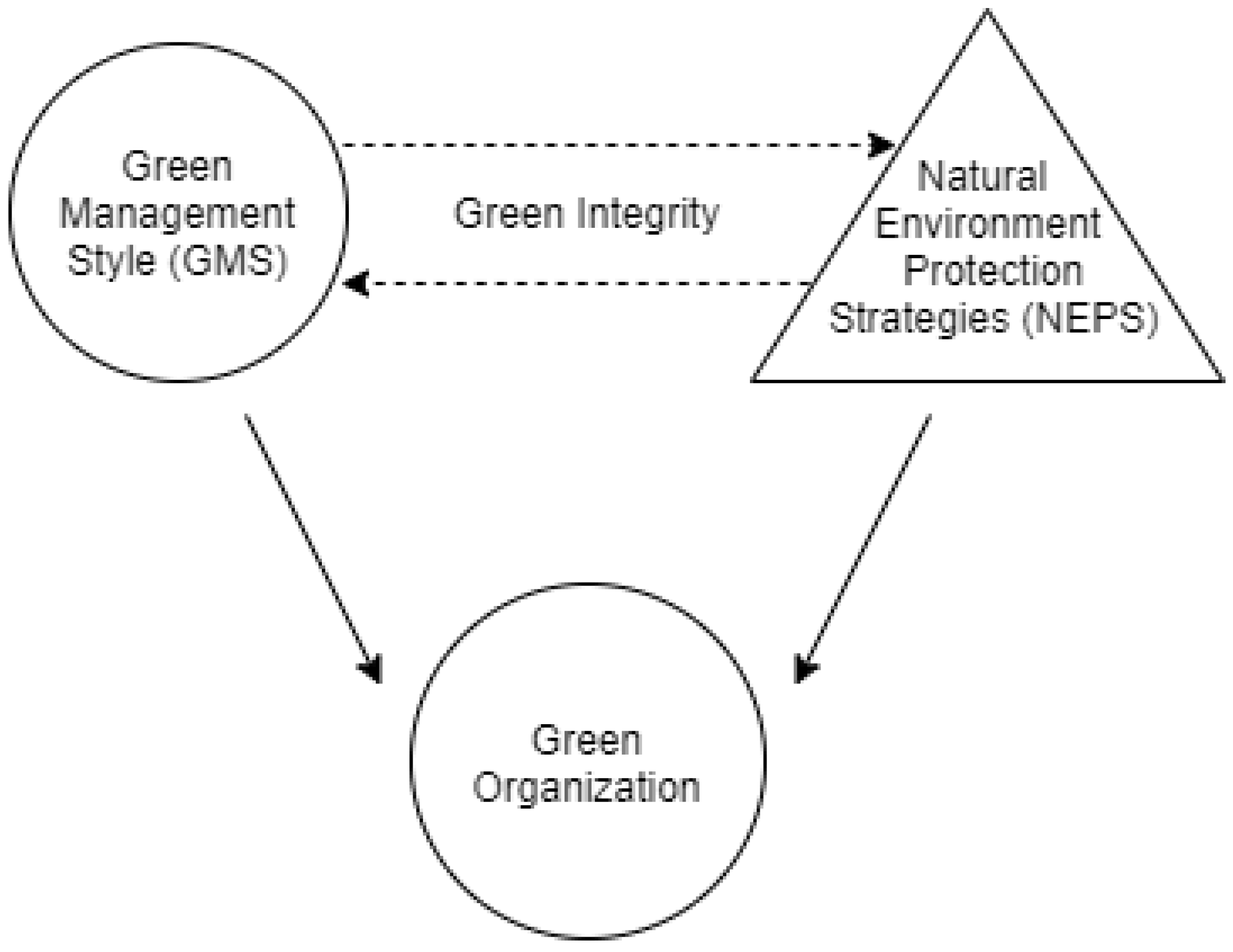

3.2.3. Green Integrity Model

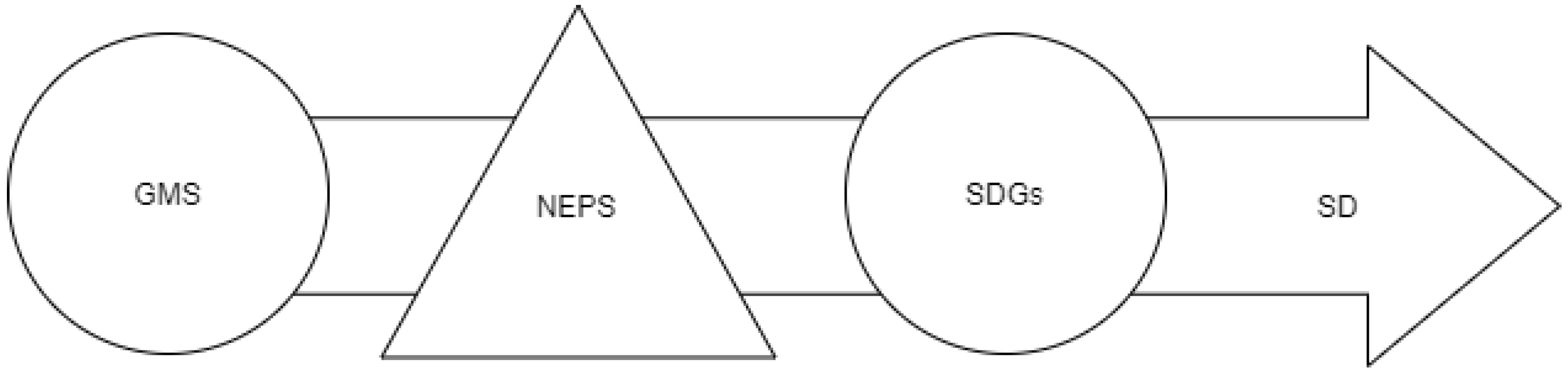

4. Discussion

5. Implications and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ciot, M.-G. Implementation Perspectives for the European Green Deal in Central and Eastern Europe. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sztorc, M. The Implementation of the European Green Deal Strategy as a Challenge for Energy Management in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Energies 2022, 15, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Majumdar, A.; Majumdar, K.; Raut, R.D.; Narkhede, B.E. Attaining sustainable development goals (SDGs) through supply chain practices and business strategies: A systematic review with bibliometric and network analyses. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Environmental Goods and Services Sector (env_egs). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/env_egs_esms.htm (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Environmental Protection Strategies for Sustainable Development; Malik, A.; Grohmann, E. (Eds.) Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 978-94-007-1590-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cudečka-Puriņa, N.; Atstāja, D.; Koval, V.; Purviņš, M.; Nesenenko, P.; Tkach, O. Achievement of Sustainable Development Goals through the Implementation of Circular Economy and Developing Regional Cooperation. Energies 2022, 15, 4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-I.; Wu, Y.-C. The influence of enterprisers’ green management awareness on green management strategy and organizational performance. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2014, 31, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, B.; Kelboro, G. Farmers’ contributions to achieving water sustainability: A meta-analytic path analysis of predicting water conservation behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino, V.; Balice, A.; Dangelico, R.M. Environmental strategies and green product development: An overview on sustainability-driven companies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2009, 18, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, G.; Greening, H.S.; Yates, K.K. Management Case Study. In Treatise on Estuarine and Coastal Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 11, pp. 31–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sapta, I.K.S.; Sudja, I.N.; Landra, I.N.; Rustiarini, N.W. Sustainability Performance of Organization: Mediating Role of Knowledge Management. Economies 2021, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.; Schrempf-Stirling, J.; Stutz, C. The Past, History, and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 166, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, K.; Bakker, K. Governance and sustainability at a municipal scale: The challenge of water conservation. Can. Public Policy 2011, 37, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. Let’s get this transition moving! Can. Public Policy 2016, 42, S10–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuffic, P.; Sotirov, M.; Arts, B. Your policy, my rationale. How individual and structural drivers influence European forest owners’ decisions. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 1024–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, M.; Sypniewska, B. The impact of management methods on employee engagement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiakou, S.; Vrahnakis, M.; Chouvardas, D.; Mamanis, G.; Kleftoyanni, V. Land Use Changes for Investments in Silvoarable Agriculture Projected by the CLUE-S Spatio-Temporal Model. Land 2022, 11, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Petison, P. A retrospective and foresight: Bibliometric review of international research on strategic management for sustainability, 1991. Sustainability 2020, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, M.; Nadeem, M.; Zaman, R. Biodiversity disclosure, sustainable development and environmental initiatives: Does board gender diversity matter? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 969–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur-Wierzbicka, E. Towards circular economy—A comparative analysis of the countries of the European Union. Resources 2021, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Bolívar, M.P. Characterizing the Role of Governments in Smart Cities: A Literature Review. Public Adm. Inf. Technol. 2016, 11, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, I.; Sadorsky, P. Environmental management practices and performance in Canada. Can. Public Policy 2013, 39, S157–S175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipsher, S.A. The Private Sector’s Role in Poverty Reduction in Asia; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; ISBN 9780857094483. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Azorin, J.F.; López-Gamero, M.D.; Tarí, J.J.; Pereira-Moliner, J.; Pertusa-Ortega, E.M. Environmental Management, Human Resource Management and Green Human Resource Management: A Literature Review. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozar, Ł.; Oleksiak, P. Organisations Facing the Challenges of Sustainable Development–Selected Aspects Organizacje Wobec Wyzwań Zrównoważonego Rozwoju–Wybrane Aspekty; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2022; ISBN 9788382208191. [Google Scholar]

- Egels-Zandén, N.; Rosén, M. Sustainable strategy formation at a Swedish industrial company: Bridging the strategy-as-practice and sustainability gap. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 96, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, F.; Farooq, S.; Boer, H. The impact of country of origin and operation on sustainability practices and performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 304, 127097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.H. Examining green policy and sustainable development from the perspective of differentiation and strategic alignment. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1096–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillebeeckx, S.J.D.; Kautonen, T.; Hakala, H. To Buy Green or Not to Buy Green: Do Structural Dependencies Block Ecological Responsiveness? J. Manag. 2022, 48, 472–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Shukla, V.; Mangla, S.; Chanchaichujit, J. Do firm characteristics affect environmental sustainability? A literature review-based assessment. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 1389–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C. Social Innovation Governance in Smart Specialisation Policies and Strategies Heading towards Sustainability: A Pathway to RIS4? Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, C.; Sova, R. EU Net-Zero Policy Achievement Assessment in Selected Members through Automated Forecasting Algorithms. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inform. 2022, 11, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, B.F.; Baer, D.; Lindkvist, C. Identifying and supporting exploratory and exploitative models of innovation in municipal urban planning; key challenges from seven Norwegian energy ambitious neighborhood pilots. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 142, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Shen, N.; Ying, H.; Wang, Q. Can environmental regulation directly promote green innovation behavior?—Based on situation of industrial agglomeration. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginter, A.; Zarzecka, K.; Gugała, M. Effect of Herbicide and Biostimulants on Production and Economic Results of Edible Potato. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowska-Woszczycka, A.; Pactwa, K. Social License for Closure—A Participatory Approach to the Management of the Mine Closure Process. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzesiak, S.; Sulich, A. Car Engines Comparative Analysis: Sustainable Approach. Energies 2022, 15, 5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birknerová, Z.; Uher, I. Assessment of Management Competencies According to Coherence with Managers’ Personalities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K. Structural and individual determinants of workplace victimization: The effects of hierarchical status and conflict management style. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmolke, A.; Thorbek, P.; DeAngelis, D.L.; Grimm, V. Ecological models supporting environmental decision making: A strategy for the future. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, L.L.; Delevaux, J.M.S.; Leary, J.J.K.; Cox, L.J.; Oleson, K.L.L. Opportunities and Strategies to Incorporate Ecosystem Services Knowledge and Decision Support Tools into Planning and Decision Making in Hawai’i. Environ. Manag. 2015, 55, 884–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, R.A.; Gunningham, N.; Thornton, D. Explaining corporate environmental performance: How does regulation matter? Law Soc. Rev. 2003, 37, 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csordás, A.; Lengyel, P.; Füzesi, I. Who Prefers Regional Products? A Systematic Literature Review of Consumer Characteristics and Attitudes in Short Food Supply Chains. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasseur, L.; You, M. Facing Climate Change Through Sustainable Agriculture: Can Results from China Be Transferred to Africa? In Agricultural Adaptation to Climate Change; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Shi, C.; Zhai, K. An evaluation of environmental governance in urban China based on a hesitant fuzzy linguistic analytic network process. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyvyanyy, A.; Ouyang, C.; Barros, A.; van der Aalst, W.M.P. Process querying: Enabling business intelligence through query-based process analytics. Decis. Support Syst. 2017, 100, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokop, V.; Gerstlberger, W.; Zapletal, D.; Striteska, M.K. The double-edged role of firm environmental behaviour in the creation of product innovation in Central and Eastern European countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 331, 129989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floress, K.; de Jalón, S.; Church, S.P.; Babin, N.; Ulrich-Schad, J.D.; Prokopy, L.S. Toward a theory of farmer conservation attitudes: Dual interests and willingness to take action to protect water quality. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zema, T.; Sulich, A. Models of Electricity Price Forecasting: Bibliometric Research. Energies 2022, 15, 5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimm, C.; Sperling, F.; Busch, S. Identifying Sustainability and Knowledge Gaps in Socio-Economic Pathways Vis-à-Vis the Sustainable Development Goals. Economies 2018, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malabagi, S.; Kulkarni, V.N.; Gaitonde, V.N.; Satish, G.J.; Kotturshettar, B.B. Product Lifecycle Management (PLM): A decision-making tool for project management. AIP Conf. Proc. 2021, 2358, 100013. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, R.E.; Anderson, L.E. Managing Outdoor Recreation: Case Studies in the National Parks; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2012; ISBN 9781845939311. [Google Scholar]

- García-Morales, V.J.; Ruiz-Moreno, A.; Llorens-Montes, F.J. Effects of technology absorptive capacity and technology proactivity on organizational learning, innovation and performance: An empirical examination. Technol. Anal. Strategy Manag. 2007, 19, 527–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Producing a systematic review. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 671–689. ISBN 978-1-4129-3118-2. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, R.; Lamond, D.; Pane Haden, S.S.; Oyler, J.D.; Humphreys, J.H. Historical, practical, and theoretical perspectives on green management: An exploratory analysis. Manag. Decis. 2009, 47, 1041–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascur, J.P.; Verberne, S.; van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Browsing citation clusters for academic literature search: A simulation study with systematic reviews. In Proceedings of the CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Lisbon, Portugal, 14 April 2020; Volume 2591, pp. 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Using qualitative research synthesis to build an actionable knowledge base. Manag. Decis. 2006, 44, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Denyer, D.; Overy, P. Sustainability-oriented Innovation: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Claver-Cortés, E.; López-Gamero, M.D.; Tarí, J.J. Green management and financial performance: A literature review. Manag. Decis. 2009, 47, 1080–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchinetti, T.; Benetti, G.; Giuffrida, D.; Nocera, A. SLR-kit: A semi-supervised machine learning framework for systematic literature reviews. Knowl. Based Syst. 2022, 251, 109266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boar, A.; Bastida, R.; Marimon, F. A Systematic Literature Review. Relationships between the Sharing Economy, Sustainability and Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.; van Eck, N.; Waltman, L. Large-scale comparison of bibliographic data sources: Web of Science, Scopus, Dimensions, and CrossRef. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Scientometrics and Informetrics, ISSI 2019–Proceedings, Rome, Italy, 2–5 September 2019; Volume 2, pp. 2358–2369. [Google Scholar]

- Bascur, J.P.; van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. An interactive visual tool for scientific literature search: Proposal and algorithmic specification. In Proceedings of the CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Cologne, Germany, 14 April 2019; Volume 2345, pp. 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, M.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Mahmood, M.; Uddin, M.A.; Biswas, S.R. Ethical leadership for better sustainable performance: Role of employee values, behavior and ethical climate. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 130527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waltman, L.; van Eck, N.J.; Wouters, P. Counting publications and citations: Is more always better? J. Informetr. 2013, 7, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L.; Dekker, R.; van den Berg, J. A comparison of two techniques for bibliometric mapping: Multidimensional scaling and VOS. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 2405–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colavizza, G.; Boyack, K.W.; van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. The Closer the Better: Similarity of Publication Pairs at Different Cocitation Levels. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2018, 69, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. How to normalize cooccurrence data? An analysis of some well-known similarity measures. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 1635–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltman, L.; van Eck, N.J. Field-normalized citation impact indicators and the choice of an appropriate counting method. J. Informetr. 2015, 9, 872–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaruga, E.; Załoga, E. Qualitative–Quantitative Warning Modeling of Energy Consumption Processes in Inland Waterway Freight Transport on River Sections for Environmental Management. Energies 2022, 15, 4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.-Z.; Waltman, L. A large-scale bibliometric analysis of global climate change research between 2001 and 2018. Clim. Chang. 2022, 170, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundurpi, A.; Westman, L.; Luederitz, C.; Burch, S.; Mercado, A. Navigating between adaptation and transformation: How intermediaries support businesses in sustainability transitions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 125366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecl, G.T.; Araújo, M.B.; Bell, J.D.; Blanchard, J.; Bonebrake, T.C.; Chen, I.C.; Clark, T.D.; Colwell, R.K.; Danielsen, F.; Evengård, B.; et al. Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: Impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. Science 2017, 355, eaai9214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buysse, K.; Verbeke, A. Proactive environmental strategies: A stakeholder management perspective. Strategy Manag. J. 2003, 24, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahtinen, S.; Yrjölä, M. Managing sustainability transformations: A managerial framing approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 223, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainbridge, J.M.; Potts, T.; O’Higgins, T.G. Rapid policy network mapping: A new method for understanding governance structures for implementation of marine environmental policy. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, I. Greening Business; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stål, H.I.; Bengtsson, M.; Manzhynski, S. Cross-sectoral collaboration in business model innovation for sustainable development: Tensions and compromises. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Yu, T.; Yi, W.; Li, Y. Twenty-year retrospection on green manufacturing: A bibliometric perspective. IET Collab. Intell. Manuf. 2021, 3, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-León, E.; Reyes-Carrillo, T.; Díaz-Pichardo, R. Towards a holistic framework for sustainable value analysis in business models: A tool for sustainable development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Zhan, X.; Zhang, H.; Xu, M.; Liu, J.; Zheng, C. How much is global business sectors contributing to sustainable development goals? Sustain. Horiz. 2022, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar-Sulej, K. Pro-environmental organizational culture: Its essence and a concept for its operationalization. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, J.; Heinz, N.; Cornelissen, G.; Le Menestrel, M. How to encourage business professionals to adopt sustainable practices? Experimental evidence that the ‘business case’ discourse can backfire. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidlerová, H.; Stareček, A.; Vraňaková, N.; Bulut, C.; Keaney, M. Sustainable Entrepreneurship for Business Opportunity Recognition: Analysis of an Awareness Questionnaire among Organisations. Energies 2022, 15, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckstrand, K. Towards a Climate-Neutral Union by 2050? The European Green Deal, Climate Law, and Green Recovery. In Routes to a Resilient European Union; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Belas, J.; Gavurova, B.; Machova, V.; Mikolas, Z. Selected factors of corporate management in SMEs sector [Wybrane czynniki zarządzania korporacyjnego w sektorze MSP]. Polish J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 21, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, G. Monsters, Catastrophes and the Anthropocene: A Postcolonial Critique; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2020; ISBN 9781351064866. [Google Scholar]

- Male, S.; Kelly, J.; Gronqvist, M.; Graham, D. Managing value as a management style for projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2007, 25, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Yang, X.; Liu, C.; Yang, W. Business strategy and firm efforts on environmental protection: Evidence from China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.; Kirwan, J. Exploring the Ecological Dimensions of Producer Strategies in Alternative Food Networks in the UK. Sociol. Ruralis 2011, 51, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutzschenreuter, T.; Kleindienst, I. Strategy-process research: What have we learned and what is still to be explored. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 673–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, S.K.; Fergus, C.E.; Skaff, N.K.; Wagner, T.; Tan, P.-N.; Cheruvelil, K.S.; Soranno, P.A. Strategies for effective collaborative manuscript development in interdisciplinary science teams. Ecosphere 2018, 9, e02206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, J.P.; Kafouros, M.; Lock, A.R. Metaphorical images of organization: How organizational researchers develop and select organizational metaphors. Hum. Relat. 2005, 58, 1545–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulich, A.; Sołoducho-Pelc, L. Renewable Energy Producers’ Strategies in the Visegrád Group Countries. Energies 2021, 14, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjed, A.; Khan, R.A.A.; Khan, M.M. Morgan metaphors of organization: A promising approach to organizational analysis over the years. J. Manag. Res. 2001, 1, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, G. Reflections on images of organization and its implications for organization and environment. Organ. Environ. 2011, 24, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtenblad, A.; Putnam, L.L.; Trehan, K. Beyond Morgan’s eight metaphors: Adding to and developing organization theory. Hum. Relat. 2016, 69, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswick, C.; Grant, D. Re-Imagining Images of Organization: A Conversation With Gareth Morgan. J. Manag. Inq. 2016, 25, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G. Commentary: Beyond Morgan’s eight metaphors. Hum. Relat. 2016, 69, 1029–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozar, Ł. Shaping the Green Competence of Employees in an Economy Aimed at Sustainable Development. Green Hum. Resour. Manag. (Zielone Zarządzanie Zasobami Ludzkimi) 2017, 6, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Laloux, F. Reinventing Organisations: A Guide to Creating Organisations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness; Nelson Parker: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova-Aguirre, L.J.; Ramón-Jerónimo, J.M. Exploring the inclusion of sustainability into strategy and management control systems in peruvian manufacturing enterprises. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bititci, U.S.; Mendibil, K.; Nudurupati, S.; Turner, T.; Garengo, P. The interplay between performance measurement, organizational culture and management styles. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2004, 8, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadas, K.K.; Avlonitis, G.J.; Carrigan, M.; Piha, L. The interplay of strategic and internal green marketing orientation on competitive advantage. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukin, E.; Krajnović, A.; Bosna, J. Sustainability Strategies and Achieving SDGs: A Comparative Analysis of Leading Companies in the Automotive Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montabon, F.; Sroufe, R.; Narasimhan, R. An examination of corporate reporting, environmental management practices and firm performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 998–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgelman, R.A. Intraorganizational Ecology of Strategy Making and Organizational Adaptation: Theory and Field Research. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisaki, K.; Shimpo, M.; Akamatsu, R. Factors related to food safety culture among school food handlers in Tokyo, Japan: A qualitative study. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2019, 22, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassi, A.A.; Bryde, D.J.; Abdullah, A.; Argyropoulou, M. Conflict Management Style of Team Leaders in Multi-Cultural Work Environment in the Construction Industry. In Proceedings of the Procedia Computer Science, Barcelona, Spain, 8–10 November 2017; Volume 121, pp. 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, Z. Wildness and Wellbeing: Nature, Neuroscience, and Urban Design; Palgrave Pivot: Devon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Suleman, Q.; Syed, M.A.; Shehzad, S.; Hussain, I.; Khattak, A.Z.; Khan, I.U.; Amjid, M.; Khan, I. Leadership empowering behaviour as a predictor of employees’ psychological wellbeing: Evidence from a cross-sectional study among secondary school teachers in Kohat Division, Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Venturi, M.; Agnoletti, M. Landscape perception and public participation for the conservation and valorization of cultural landscapes: The case of the cinque terre and porto venere unesco site. Land 2021, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A. The Resource-Based View, Resourcefulness, and Resource Management in Startup Firms: A Proposed Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1841–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Concepción, A.; Gil-Lacruz, A.I.; Saz-Gil, I. Stakeholder engagement, CSR development and SDGs compliance: A systematic review from 2015 to 2021. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laszlo, C. The Sustaianble Company; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brodt, S.; Klonsky, K.; Tourte, L. Farmer goals and management styles: Implications for advancing biologically based agriculture. Agric. Syst. 2006, 89, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielcarek, P. Strategic Coherence and Process Maturity in the Context of Company Ambidextrousness; C.H. Beck: Warsaw, Poland, 2021; ISBN 978-83-8235-568-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, K.; Thomas, S.; Rosano, M. Using industrial ecology and strategic management concepts to pursue the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/policies/sustainable-development-goals_en (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Kopnina, H. Sustainability: New strategic thinking for business. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2017, 19, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawicka, E. Sustainable business strategies as an element influencing diffusion on innovative solutions in the field of renewable energy sources. Energies 2021, 14, 5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayambire, R.A.; Pittman, J. Opening the black box between governance and management: A mechanism-based explanation of how governance affects the management of endangered species. Ambio 2022, 51, 2091–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona-Moreno, E.; Céspedes-Lorente, J.; de Burgos-Jiménez, J. Environmental strategies in Spanish hotels: Contextual factors and peformance. Serv. Ind. J. 2004, 24, 101–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvancarova, Z.; Franek, J. Corporate governance development in Central and Eastern Europe. Actual Probl. Econ. 2016, 179, 122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Attanasio, G.; Preghenella, N.; De Toni, A.F.; Battistella, C. Stakeholder engagement in business models for sustainability: The stakeholder value flow model for sustainable development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 860–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Strategic attributions of corporate social responsibility and environmental management: The business case for doing well by doing good! Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, A.; Haapanen, L.; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P.; Tarba, S.Y.; Alon, I. Climate change, consumer lifestyles and legitimation strategies of sustainability-oriented firms. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossai, C.I.; Boswell, B.; Davies, I.J. Sustainable asset integrity management: Strategic imperatives for economic renewable energy generation. Renew. Energy 2014, 67, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztel, H.; Hinz, O. Changing organisations with metaphors. Learn. Organ. 2001, 8, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, Y. Narrative Ecologies and the Role of Counter-Narratives: The Case of Nostalgic Stories and Conspiracy Theories; Taylor and Francis Inc.: Abingdon, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781317399490. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Aragón-Correa, J.A.; Marano, V.; Tashman, P.A. The Corporate Governance of Environmental Sustainability: A Review and Proposal for More Integrated Research. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1468–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qi, S.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, J.; Huang, X. Green credit policy, government behavior and green innovation quality of enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 331, 129834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Miller, D. People matter: Commitment to employees, strategy and performance in Korean firms. Strategy Manag. J. 1999, 20, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroozesh, N.; Karimi, B.; Mousavi, S.M. Green-resilient supply chain network design for perishable products considering route risk and horizontal collaboration under robust interval-valued type-2 fuzzy uncertainty: A case study in food industry. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 307, 114470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sołoducho-Pelc, L.; Sulich, A. Between Sustainable and Temporary Competitive Advantages in the Unstable Business Environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhloufi, L.; Laghouag, A.A.; Meirun, T.; Belaid, F. Impact of green entrepreneurship orientation on environmental performance: The natural resource-based view and environmental policy perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerst, M.; Schotter, A. Strategic Integrity Management as a Dynamic Capability. In Strategic Management in the 21st Century; Wilkinson, T., Kannan, V.R., Eds.; Praeger Publishers: Westport, CT, USA, 2013; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, N.M.; Kiet, W.W.; Saat, M.M.; Othman, A. A relationship analysis between green supply chain practices, environmental management accounting and performance. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2020, 15, 113–131. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J.S.; Barney, J.B.; Freeman, R.E.; Phillips, R.A. Stakeholder Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; ISBN 9781108123495. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, Y. Organizations in a State of Darkness: Towards a Theory of Organizational Miasma. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 1137–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-P.; Wen, J.; Zheng, M. Environmental governance and innovation: An overview. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 12720–12721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozar, Ł. Green Jobs. Determinants–Identification–Impact on the Local Labour Market Zielone Miejsca Pracy. Uwarunkowania–Identyfikacja–Oddziaływanie Na Lokalny Rynek Pracy; Uniwersytet Łódzki: Łódź, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stanef-Puică, M.-R.; Badea, L.; Șerban-Oprescu, G.-L.; Șerban-Oprescu, A.-T.; Frâncu, L.-G.; Crețu, A. Green Jobs—A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulich, A.; Zema, T. Green jobs, a new measure of public management and sustainable development. Eur. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 8, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulich, A.; Sołoducho-Pelc, L. The circular economy and the Green Jobs creation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 14231–14247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trovato, M.R.; Cappello, C. Climate Adaptation Heuristic Planning Support System (HPSS): Green-Blue Strategies to Support the Ecological Transition of Historic Centres. Land 2022, 11, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemczyk, J.; Sus, A.; Bielińska-Dusza, E.; Trzaska, R.; Organa, M. Strategies of European Energy Producers: Directions of Evolution. Energies 2022, 15, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.M. The Eight ‘S’s of successful strategy execution. J. Chang. Manag. 2005, 5, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notaro, S.; Lovera, E.; Paletto, A. Consumers’ preferences for bioplastic products: A discrete choice experiment with a focus on purchase drivers. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-K.; Lujan-Blanco, I.; Fortuny-Santos, J.; Ruiz-de-Arbulo-López, P. Lean Manufacturing and Environmental Sustainability: The Effects of Employee Involvement, Stakeholder Pressure and ISO 14001. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegarden, L.F.; Sarason, Y.; Childers, J.S.; Hatfield, D.E. the Engagement of Employees in the Strategy Process and Firm Performance. J. Bus. Strategy 2005, 22, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. Technological thinking: Its impact on environmental management. Environ. Manag. 1985, 9, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascher, W. Long-term strategy for sustainable development: Strategies to promote far-sighted action. Sustain. Sci. 2006, 1, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E.G. Creating an enterprise-level ‘green’ strategy. J. Bus. Strategy 2008, 29, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravcikova, D.; Krizanova, A.; Kliestikova, J.; Rypakova, M. Green marketing as the source of the competitive advantage of the business. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, C.; Ackermann, F. Making Strategy: The Journey of Strategic Management; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, G. Employee engagement: What’s your strategy? Strategy HR Rev. 2018, 17, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins-Loução, M.A.; Dias, T.; Cruz, C. Integrating Ecological Principles for Addressing Plant Production Security and Move beyond the Dichotomy ‘Good or Bad’ for Nitrogen Inputs Choice. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moini, H.; Sorensen, O.J.; Szuchy-Kristiansen, E. Adoption of green strategy by Danish firms. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2014, 5, 197–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Kim, Y.; Han, K.; Jackson, S.E.; Ployhart, R.E. Multilevel Influences on Voluntary Workplace Green Behavior: Individual Differences, Leader Behavior, and Coworker Advocacy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1335–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borin, N.; Lindsey-Mullikin, J.; Krishnan, R. An analysis of consumer reactions to green strategies. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2013, 22, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speculand, R. Beyond Strategy: The Leaders Role in Successful Implementation. Strateg. Dir. 2011, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.Y.A.; Sasmita, P. Engaging employees through balanced scorecard implementation. Startegic HR Rev. 2013, 12, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, B. Changing environmental strategies over time: An empirical study of the steel industry in the United States. J. Environ. Manag. 2001, 62, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousali, C.; Besseris, G. Lean Screening for Greener Energy Consumption in Retrofitting a Residential Apartment Unit. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lieshout, J.W.; Nijhof, A.H.J.; Naarding, G.J.W.; Blomme, R.J. Connecting strategic orientation, innovation strategy, and corporate sustainability: A model for sustainable development through stakeholder engagement. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 4068–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, H.J. Environmental proactivity of hotel operations: Antecedents and the moderating effect of ownership type. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier-Meek, M.A.; Johnson, A.H.; Sanetti, L.M.H. Evaluating the Fit of the Ecological Framework for Implementation Variables. Assess. Eff. Interv. 2019, 45, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colby, M.E. Environmental management in development: The evolution of paradigms. Ecol. Econ. 1991, 3, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, S.R. Green management: The next competitive weapon. Futures 1992, 24, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Grenville, J.A. Inside the ‘black box’: How organizational culture and subcultures inform interpretations and actions on environmental issues. Organ. Environ. 2006, 19, 46–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Query Syntax | No. of Results (10 August 2022) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (ALL (natural AND environment AND protection AND strategies)) AND (“management style”) | 164 |

| 2 | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (natural AND environment AND protection AND strategies)) AND (“management style”) | 2 |

| 3 | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“environmental strategies”)) AND (“management style”) | 1 |

| 4 | TITLE-ABS-KEY (((environmental AND strategies)) AND (((management AND style)) AND (natural AND environment AND protection)) AND (conservation)) | 7 |

| 5 | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (environmental AND strategies)) AND (((management AND style)) AND (natural AND environment AND protection)) AND (conservation) | 345 |

| 6 | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (environmental AND strategies)) AND (management AND style) AND (natural AND environment AND protection) AND (conservation) AND (“management style”) | 20 |

| 7 | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (environmental strategies)) AND (((((management style)) AND (natural environment protection)) AND (conservation)) AND (“management style”)) AND (“protection strategies”) | 0 |

| Cluster | Color | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Red | climate change; decision making; environmental impact; environmental management; environmental protection; forestry; stakeholder; sustainable development |

| 2 | Green | agricultural land; agricultural management; agriculture; farmers attitude; farming system; innovation; management practice; perception |

| 3 | Blue | adaptive management; biodiversity; conservation management; ecosystem service, incentive; resource management |

| 4 | Yellow | animals; human; nonhuman; review |

| Cluster | Color | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Red | adaptive management; climate change; decision making; ecology; ecosystem; ecosystem service; environmental monitoring; environmental planning; rivers; water management; water quality; |

| 2 | Green | adaptation; environmental impact; environmental issue; environmental management; life cycle; natural resource; stakeholder; sustainability; sustainable development; |

| 3 | Blue | conservation of natural resources; economics; environmental economics; environmental policy; environmental protection; government; strategic approach; |

| 4 | Yellow | agricultural land; agriculture; biodiversity; conservation; conservation management; land management; |

| Common Keywords |

|---|

| climate change; decision making; environmental impact; environmental management; environmental protection; stakeholder; sustainable development; agricultural land; adaptive management; biodiversity; conservation management; ecosystem service; |

| Cluster | Color | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Red | adaptive environmental management; climate change; conservation of natural resources; decision making; ecology; management practice; management style; strategic planning; |

| 2 | Green | ecosystem services; environmental policy; environmental quality; incentive; land management; natural resource; strategic approach; |

| 3 | Blue | community resource management; conservation management; environmental management; stakeholder; sustainability; sustainable development; |

| 4 | Yellow | environmental protection; management; public policy |

| Cluster | Color | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Red | decision making; environment management; land management |

| 2 | Green | conservation of natural resources; environmental protection; |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sołoducho-Pelc, L.; Sulich, A. Natural Environment Protection Strategies and Green Management Style: Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710595

Sołoducho-Pelc L, Sulich A. Natural Environment Protection Strategies and Green Management Style: Literature Review. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):10595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710595

Chicago/Turabian StyleSołoducho-Pelc, Letycja, and Adam Sulich. 2022. "Natural Environment Protection Strategies and Green Management Style: Literature Review" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 10595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710595

APA StyleSołoducho-Pelc, L., & Sulich, A. (2022). Natural Environment Protection Strategies and Green Management Style: Literature Review. Sustainability, 14(17), 10595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710595