Avoidance of Supermarket Food Waste—Employees’ Perspective on Causes and Measures to Reduce Fruit and Vegetables Waste

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mixed Methods Research Design

2.2. Descriptions of the Stores

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Field Visits

- Store visit 1: interview in the back office of the store (1 employee), participating observations in the FV department (2 employees), field notes and photos on site, compiling memory notes;

- Store visit 2: interview in the back office of the store (1 employee), participating observations in the FV department (2 employees), interview in the FV department (1 employee), field notes and photos on site, compiling memory notes;

- Collecting data from the database on food waste kept by the store;

- Follow-up telephone call (1 employee), compiling memory notes;

- Processing and analysis of qualitative data (interviews and observations);

- Processing and analysis of quantitative data (waste data from the stores);

- Respondent validation: presentation and discussion of results (1 employee), compiling memory notes.

2.3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.3.3. Participatory Observations

2.3.4. Waste Data from the Stores

2.4. Data Analyses

2.5. Delimitations

2.6. Ethical Considerations

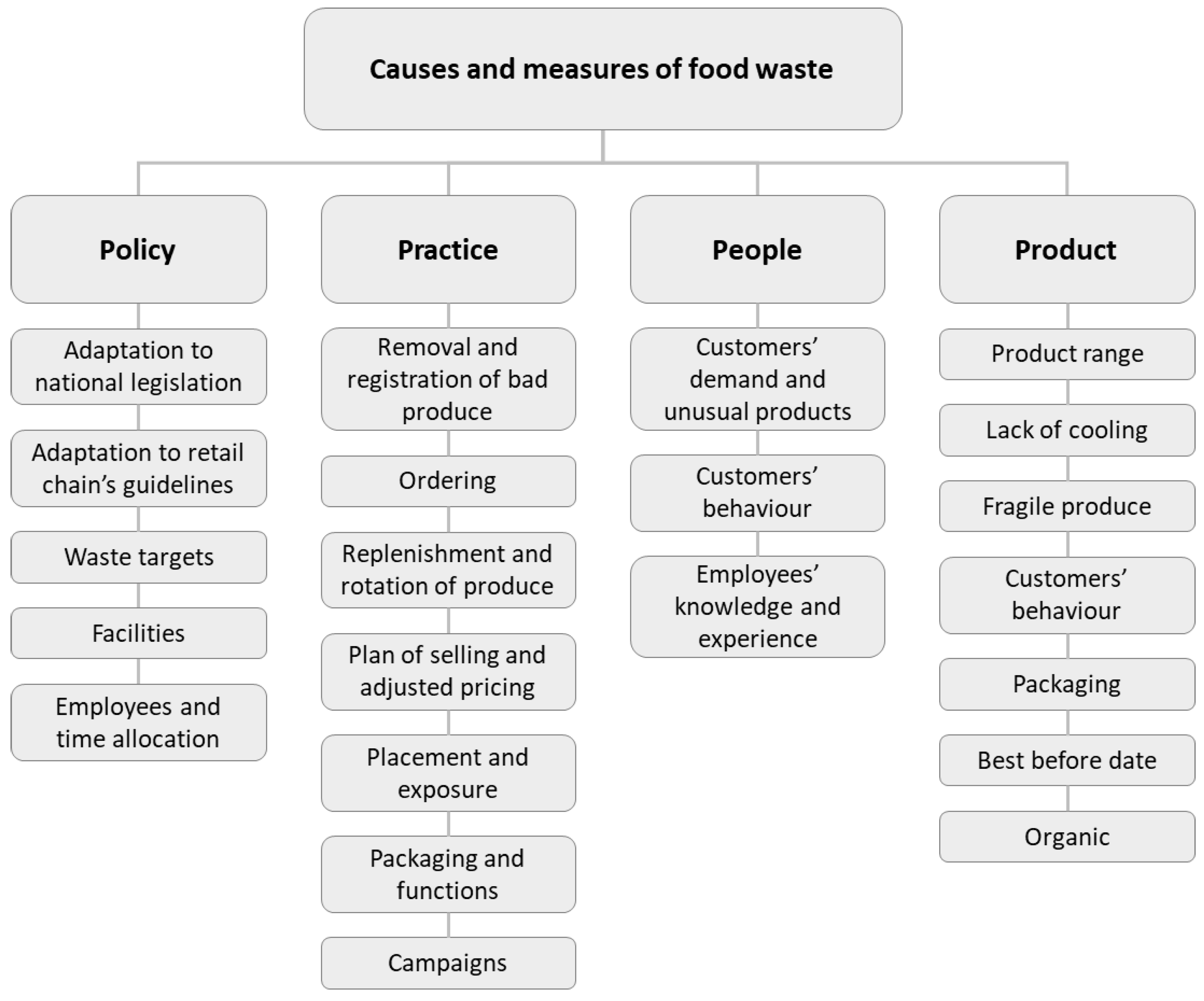

3. Results

3.1. Policy

3.2. Practice

3.2.1. Removal and Registration of Bad Produce

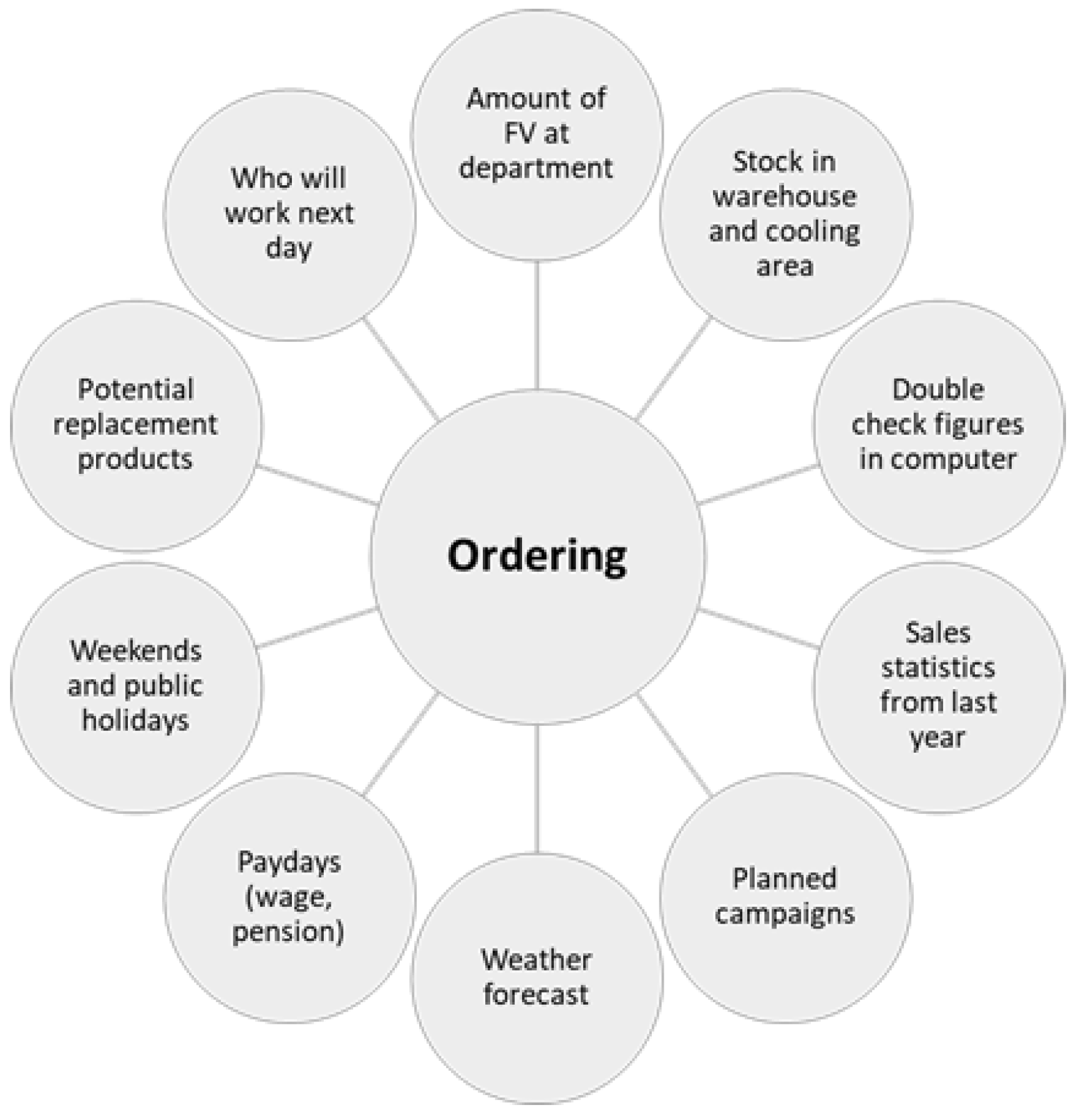

3.2.2. Ordering

3.2.3. Replenishment and Rotation of Produce

3.2.4. Plan of Selling and Adjusted Pricing

3.2.5. Placement and Exposure

3.2.6. Packaging and Functions

3.2.7. Campaigns

3.3. People

3.3.1. Customers’ Demand and Unusual Products

3.3.2. Customers’ Behaviour

3.3.3. Employees’ Knowledge and Experience

3.4. Product

3.4.1. Amount of Food Waste

3.4.2. Product-Specific Causes

4. Discussion

4.1. The Central Role of Employees

4.2. Product-Specific Causes

4.3. An Overview of Causes and Measures: Policy, Practice, People, Product

4.4. The Use of Results and Future Work

4.5. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Shukla, J.S.P.R., Calvo Buendia, E., Masson-Delmotte, V., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Zhai, P., Slade, R., Connors, S., van Diemen, R., Ferrat, M., et al., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Papargyropoulou, E.; Lozano, R.; Steinberger, J.K.; Wright, N.; bin Ujang, Z. The food waste hierarchy as a framework for the management of food surplus and food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obadi, M.; Ayad, H.; Pokharel, S.; Ayari, M.A. Perspectives on food waste management: Prevention and social innovations. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 31, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeswani, H.K.; Figueroa-Torres, G.; Azapagic, A. The extent of food waste generation in the UK and its environmental impacts. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 532–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; de Hooge, I.; Amani, P.; Bech-Larsen, T.; Oostindjer, M. Consumer-Related Food Waste: Causes and Potential for Action. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6457–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikovskaja, V.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. Food Waste Avoidance Actions in Food Retailing: The Case of Denmark. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2017, 29, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Food Losses and Food Waste—Extent, Causes and Prevention; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vadakkepatt, G.G.; Winterich, K.P.; Mittal, V.; Zinn, W.; Beitelspacher, L.; Aloysius, J.; Ginger, J.; Reilman, J. Sustainable Retailing. J. Retail. 2021, 97, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, C.; Stoessel, F.; Baier, U.; Hellweg, S. Quantifying food losses and the potential for reduction in Switzerland. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicatiello, C.; Franco, S.; Pancino, B.; Blasi, E. The value of food waste: An exploratory study on retailing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 30, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebersorger, S.; Schneider, F. Food loss rates at the food retail, influencing factors and reasons as a basis for waste prevention measures. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 1911–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancoli, P.; Rousta, K.; Bolton, K. Life cycle assessment of supermarket food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 118, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicatiello, C.; Franco, S.; Pancino, B.; Blasi, E.; Falasconi, L. The dark side of retail food waste: Evidences from in-store data. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125 (Suppl. C), 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Smith, F.; Mirosa, M.; Skeaff, S. A mixed-methods study of retail food waste in New Zealand. Food Policy 2020, 92, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, C.; Adenso-Diaz, B.; Yurt, O. The causes of food waste in the supplier? Retailer interface: Evidences from the UK and Spain. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, K.; Eriksson, M.; Strid, I. Carbon footprint of supermarket food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 94, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilska, B.; Piecek, M.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. A Multifaceted Evaluation of Food Waste in a Polish Supermarket—Case Study. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech-Larsen, T.; Esbjerg, L. The Garden of the Self-Service Store. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2006, 12, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teller, C.; Holweg, C.; Reiner, G.; Kotzab, H. Retail store operations and food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 981–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicatiello, C.; Blasi, E.; Giordano, C.; Martella, A.; Franco, S. “If only I Could Decide”: Opinions of Food Category Managers on in-Store Food Waste. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horoś, I.K.; Ruppenthal, T. Avoidance of Food Waste from a Grocery Retail Store Owner’s Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Gherbin, A. An exploratory study of food waste management practices in the UK grocery retail sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 1184–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, V.; Holweg, C.; Teller, C. What a Waste! Exploring the Human Reality of Food Waste from the Store Manager’s Perspective. J. Public Policy Mark. 2016, 35, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moraes, C.C.; de Oliveira Costa, F.H.; Pereira, C.R.; Da Silva, A.L.; Delai, I. Retail food waste: Mapping causes and reduction practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, C.; Dhir, A.; Akram, M.U.; Salo, J. Food loss and waste in food supply chains. A systematic literature review and framework development approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, L.; Williams, H.; Berghel, J. Waste of fresh fruit and vegetables at retailers in Sweden—Measuring and calculation of mass, economic cost and climate impact. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 130, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priefer, C.; Jörissen, J.; Bräutigam, K.-R. Food waste prevention in Europe—A cause-driven approach to identify the most relevant leverage points for action. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 109, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, O.J.; Stenmarck, A.; Werge, M.; Silvennoinen, K.; Katajajuuri, J.-M. Initiatives on Prevention of Food Waste in the Retail and Wholesale Trades; IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute Ltd.: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thyberg, K.L.; Tonjes, D.J. Drivers of food waste and their implications for sustainable policy development. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 106, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verghese, K.; Lewis, H.; Lockrey, S.; Williams, H. Packaging’s Role in Minimizing Food Loss and Waste Across the Supply Chain. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2015, 28, 603–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Strid, I.; Hansson, P.-A. Waste of organic and conventional meat and dairy products—A case study from Swedish retail. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 83, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; de Hooge, I.; Normann, A. Consumer-Related Food Waste: Role of Food Marketing and Retailers and Potential for Action. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2016, 28, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Liu, G.; Parfitt, J.; Liu, X.; Van Herpen, E.; Stenmarck, Å.; O’Connor, C.; Östergren, K.; Cheng, S. Missing Food, Missing Data? A Critical Review of Global Food Losses and Food Waste Data. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6618–6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, I.Y.; Manning, L.; James, K.L.; Grigoriadis, V.; Millington, A.; Wood, V.; Ward, S. Food waste management: A review of retailers’ business practices and their implications for sustainable value. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 125484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on Waste and Repealing Certain Directives. 2008. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/topics/waste-and-recycling/waste-framework-directive_en (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- United Nations. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. 2015. Available online: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- European Commission. A New Circular Economy Action Plan For a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe COM/2020/98 Final. 2020. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/policy-documents/com-2020-98-final-a (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Ivankova, N.V.; Creswell, J.W.; Stick, S.L. Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice. Field Methods 2006, 18, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L.; Gutmann, M.L.; Hanson, W.E. An Expanded Typology for Classifying Mixed Methods Research into Designs. In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research; Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S.; Brinkmann, S. Den Kvalitativa Forskningsintervjun; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; SAGE: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Denscombe, M. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Research Projects, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Maidenhead, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, C.M. Classifications of retail stores and shopping centres: Some methodological issues. GeoJournal 1998, 45, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICA. ICA Sweden. 2022. Available online: https://www.icagruppen.se/en/about-ica-gruppen/our-operations/ica-sweden/ (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Cicatiello, C.; Franco, S. Disclosure and assessment of unrecorded food waste at retail stores. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwalbe, M.L.; Wolkomir, M. Interviewing men. In Handbook of Interview Research; Gubrium, J.F., Holstein, J.A., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, E.A. Open-Ended Interviews, Power, and Emotional Labor. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 2007, 36, 318–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Strid, I.; Hansson, P.-A. Food losses in six Swedish retail stores: Wastage of fruit and vegetables in relation to quantities delivered. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 68, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Ghosh, R.; Mattsson, L.; Ismatov, A. Take-back agreements in the perspective of food waste generation at the supplier-retailer interface. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 122, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holweg, C.; Teller, C.; Kotzab, H. Unsaleable grocery products, their residual value and instore logistics. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2016, 46, 634–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, V.S.; Ferreira, L.M.D.; Silva, C. Prioritising food loss and waste mitigation strategies in the fruit and vegetable supply chain: A multi-criteria approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 31, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, T.; Fink, C. The Comprehensive Business Case for Sustainability. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S.; Van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argyris, C. On Organizational Learning, 2nd ed.; Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| Respondent | Store | Gender | Years of Work Experience at FV Department | Interview (Approx. Min) | Observation (Approx. Min) | Follow-Up Call (Approx. Min) | Respondent Validation (Approx. Min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employee A1 | A | F | 33 | 90, 120, 30 | 60, 60, 90, 90 | 30 | 70 |

| Employee A2 | A | F | 10 | - | 60, 60, 90, 90 | - | - |

| Employee B1 | B | F | 22 | 60, 60, 60 | 60, 90, 90 | 60 | 45 |

| Employee B2 | B | F | 6 | - | 30 | - | - |

| Employee B3 | B | M | 4 | - | 30 | - | - |

| Employee C1 | C | M | 20 | 90, 90, 30 | 60, 90, 90 | 30 | 60 |

| Employee C2 | C | F | 1 | - | 30, 45, 45 | - | - |

| FV Category | Wasted Mass [kg] | Waste Quota [%] | Share Packaged [%] | Waste Quota Packaged [%] | Waste Quota Unpackaged [%] | Share Organic [%] | Waste Quota Organic [%] | Waste Quota Conventional [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potato | 5600 | 0.6 | 51 | 1.1 | 0.1 | * | - | - |

| Banana | 4800 | 1.0 | 45 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 45 | 1.3 | 0.8 |

| Apple | 4600 | 1.6 | 8 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 5 | 3.6 | 1.5 |

| Melon | 4500 | 1.8 | * | - | - | 5 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

| Lettuce | 3600 | 2.8 | 100 | 2.8 | - | 9 | 6.1 | 2.5 |

| Tomato | 3500 | 1.2 | 58 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 5 | 3.6 | 1.1 |

| Pear | 3500 | 3.6 | 26 | 4.8 | 3.2 | * | - | - |

| Sweet pepper | 3100 | 3.1 | 48 | 2.1 | 4.0 | * | - | - |

| Orange | 2900 | 1.3 | 33 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 7 | 3.3 | 1.2 |

| Clementine | 2100 | 1.1 | 26 | 2.4 | 0.6 | * | - | - |

| Grape | 1600 | 1.4 | 98 | 1.3 | 11.0 | * | - | - |

| Cabbage | 1500 | 1.6 | 21 | 4.6 | 0.7 | 5 | 3.6 | 1.5 |

| Nectarine | 1300 | 2.2 | 47 | 3.3 | 1.2 | * | - | - |

| Carrot | 1300 | 0.6 | 91 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 17 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| Berry | 1200 | 2.8 | 100 | 2.8 | - | * | - | - |

| Onion | 1000 | 0.4 | 33 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 5 | 1.4 | 0.4 |

| Cucumber | 900 | 0.6 | 100 | 0.6 | - | * | - | - |

| Avocado | 900 | 1.4 | 48 | 1.5 | 1.2 | * | - | - |

| Lemon | 900 | 1.7 | 5 | 5.6 | 1.5 | * | - | - |

| FV Category | Product Range | Lack of Cooling | Fragile Produce | Customers’ Behaviour | Packaging | Best Before Date | Organic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potato | x | x | x | ||||

| Banana | x | x | x | x | |||

| Apple | x | x | x | ||||

| Melon | x | x | x | ||||

| Lettuce | x | x | x | x | |||

| Tomato | x | x | x | x | |||

| Pear | x | x | x | ||||

| Sweet pepper | x | x | |||||

| Orange | x | x | |||||

| Clementine | x | ||||||

| Grape | x | x | |||||

| Cabbage | x | x | x | x | |||

| Nectarine | x | x | |||||

| Carrot | x | x | |||||

| Berry | x | x | |||||

| Onion | x | x | x | ||||

| Cucumber | x | ||||||

| Avocado | x | x | |||||

| Lemon | x | x |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mattsson, L.; Williams, H. Avoidance of Supermarket Food Waste—Employees’ Perspective on Causes and Measures to Reduce Fruit and Vegetables Waste. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610031

Mattsson L, Williams H. Avoidance of Supermarket Food Waste—Employees’ Perspective on Causes and Measures to Reduce Fruit and Vegetables Waste. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):10031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610031

Chicago/Turabian StyleMattsson, Lisa, and Helén Williams. 2022. "Avoidance of Supermarket Food Waste—Employees’ Perspective on Causes and Measures to Reduce Fruit and Vegetables Waste" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 10031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610031

APA StyleMattsson, L., & Williams, H. (2022). Avoidance of Supermarket Food Waste—Employees’ Perspective on Causes and Measures to Reduce Fruit and Vegetables Waste. Sustainability, 14(16), 10031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610031