Abstract

This study identifies to what extent DAX40 companies integrate ESG rating information into their reporting and whether the disclosure of ESG ratings results has a positive impact on professional and non-professional stakeholders, and thus represents a benefit for the reporting company. Our study shows that 82.5% of DAX40 companies report ESG rating results and we find that the disclosure of ESG rating results is a useful method for reporting companies (compared to non-reporters), as it leads to higher stock prices and better reputations. Considering that ESG rating results can differ substantially among different agencies, therefore, even companies with mixed ESG rating results benefit from reporting. In addition, our results support the literature that non-professional stakeholders use low-threshold information offers as an information channel. We show that companies that additionally report their ESG rating results on company websites generate higher reputation scores compared to companies that do not report their rating results on their websites.

1. Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a strategy in which environmental and social aspects as economic aspects are assigned equal importance [1] (p. 2). Given the issues of climate change, resource scarcity and social inequality, CSR is playing an increasingly important role in sustainability discussions [2] (p. 1). Investors in the capital market are also showing rising interest in this topic, as CSR performance has become an increasingly relevant investment criterion for many stakeholders [3]. In 2018-2020 the number of sustainable and responsible investments increased by over 15% [4] (p. 5). Additionally, studies have shown that sustainability-related information is relevant for not only investors, but also non-professional stakeholders who show an increasing interest in a sustainable corporate orientation [5,6]. Cheng et al. (2015) noted that society is increasingly considering sustainability while evaluating a company [7]. In this context, studies have found that strong CSR performance has a positive impact on a company’s reputation and can therefore be relevant for its relationship with non-professional stakeholders [8,9]. In connection with the rising demand for CSR, interest in sustainability information has also been growing. Companies use business and sustainability reports to maintain the legitimacy of their business models. By communicating their CSR strategies, CSR goals and the nonfinancial impacts of their corporate activities, companies can signal their responsibility to stakeholders [10].

Since the implementation of the EU CSR Directive 2014/95/EU into national law, sustainability reporting has become mandatory for large capital-market-oriented companies in Germany. However, there is considerable leeway in reporting due to extensive options for selecting frameworks and the wide range of design options for reporting formats and content within these frameworks. Studies have shown that reporting quality varies widely in terms of its scope and depth [11]. Sustainability reports are therefore often only comparable to a limited extent for stakeholders, so it can be difficult or investors to make efficient investment decisions based solely on (inhomogeneous) nonfinancial reports [12] (p. 116). Additionally, due to comprehensive requirements, the nonfinancial reports can comprise several hundred pages, so the risk of information overload exists. It is difficult, especially for non-professional stakeholders, to identify and assess information in terms of quantity and quality. Thus, merely having a sustainability report does not automatically mean that a company is sustainable; companies can use the nonfinancial reporting to engage in a kind of greenwashing and present selected CSR success stories without making fundamental changes to their corporate policy. Waivers concerning the concretization of the report content and the material audit obligation of the reports thus lead to a considerable restriction concerning required transparency. Sustainability ratings, which are produced by rating agencies based on an objective assessment of a company’s sustainability performance, aim to address these problems, and provide stakeholders with useful information [13]. Various rating agencies produce sustainability ratings even without being commissioned to do so by companies. Consequently, a whole range of ESG ratings exist for many listed companies. However, these ratings differ in their outcomes based on different priorities and weight factors [14,15,16]. Therefore, stakeholders must consult a variety of sources to obtain a comprehensive CSR assessment for a company.

Many studies have separately addressed the impact of sustainability reporting and ESG ratings. Some studies have examined the impact of sustainability reporting on financial and corporate performance [17,18,19]. There is overwhelming agreement that investors are assigning sustainability reporting an increasingly important role in investment decisions [20,21,22]. Other studies have investigated the impact of ESG rating outcomes on financial performance [23], and on CSR-related corporate behavior [24,25,26]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no studies exist that combine both aspects and consider the impact of additional and objective sustainability information via ESG ratings in sustainability reporting on companies’ stakeholders, which is the starting point of the present paper.

Research Question

CSR becoming an important issue for stakeholders has led to increasing demand for CSR-related information from companies [5,6]. In addition to the significant increase in CSR-related requirements of stakeholders, an intensification of regulations to promote CSR is discernible. In particular, the implementation of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which will lead to a considerable expansion of the number of companies required to report, represents an important regulatory change. In Germany only large capital-marketed companies have been obliged to report on sustainability till now; however, with the implementation of the CSRD, CSR reporting will become mandatory for companies that are not capital-market oriented. With the implementation of the directive, non-financial reporting is being given the same importance as financial reporting, leading to a European-wide reporting standard. For companies that have already been required to report on their non-financial actions since 2017, alignment to reporting which addresses the needs of stakeholders should be the reporting quality benchmark. Studies show that stakeholders attach great importance to comprehensive disclosure of CSR information [27,28,29]. It can therefore play an important role for companies with reporting obligations in providing additional CSR-related external information, such as ESG rating results. This study makes an important contribution in this research area by highlighting the effect of external reporting quality measures.

Companies that have so far achieved advantages against competitors just through the publication of a voluntary report must now find other ways to stand out positively. In this context, studies show that voluntary sustainability reports have a lower reporting depth and quality than those prepared in response to a legal requirement [30,31,32]. Consequently, it is conceivable that even non-capital market-oriented companies that are experienced in reporting adjust their reporting to serve the information needs of stakeholders. Thus, our study also contributes to non-capital-market-oriented companies by providing implications for companies’ reporting strategies. Furthermore, the study links to important theories that have already been used in other studies to explain the content of CSR reporting. The study contributes to companies that will be affected by the CSRD and companies that already provide CSR reports. As both the report and ESG ratings are useful sources of information on the company’s sustainability performance, we investigate whether integrating rating results from the most important rating agencies into sustainability reporting influences stakeholder perceptions and thus has an impact on the company’s performance. This approach can reduce the lack of comparability and interpretation problems resulting from verbal descriptions. Additionally, if this approach is taken, stakeholders no longer must independently search for various ESG rating results. Related to this, we ask the following research questions which are addressed in the descriptive results:

Q1. Are ESG rating results integrated into annual and sustainability reports?

Q2. Does the integration of ESG ratings impact the perception of the company by stakeholders and is therefore associated with advantages (or disadvantages) for the company?

We limit the investigation to DAX 40 companies, as they have been assessed by many ESG rating agencies due to their significant role in Germany and have many years of reporting experience (having been obliged to report since 2017) and sufficient resources to ensure comprehensive reporting [33] (p. 80).

In the first step, we investigate whether information on ESG ratings is included in reports of DAX 40 companies and how these companies deal with ESG rating disagreements. Based on a manual evaluation of the annual and sustainability reports of DAX40, we show that 29 of the 40 DAX companies report at least one ESG rating result. Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI), Sustainalytics, and ISS are the most frequently known rating agencies. In the second step, we examine how the corporate reporting of ESG rating results affects professional stakeholders (investors) and non-professional stakeholders (i.e., consumers). For our analysis of the impact of reporting ESG rating results, we use share price developments to measure the effect on investors and the consumer reputation of DAX companies to measure the effect on non-professional stakeholders. Our proxy for corporate reputation results from the YouGov BrandIndex, which is provided by the YouGov Group, an international research data and analytics group. BrandIndex is based on the perceptions of non-professional stakeholders from thousands of consumer interviews across more than fifty-five markets. Our findings show that in general, it is advantageous for companies to report ESG rating results, as we find higher stock prices for companies that disclose their ESG rating results. We specifically find evidence that transparency plays a crucial role in reporting; therefore, companies with mixed results also benefit from reporting. Additionally, our results confirm the literature stating that non-professional stakeholders tend to be less interested in annual reports than professional stakeholders due to time restrictions [34] or their insufficient ability to process and evaluate such information [35]. Instead, non-professional stakeholders use low-threshold information offers (through company websites) as an information channel. Our results imply that ESG-rated companies gain positive effects from additionally reporting their rating results on company websites as they generate higher reputation scores than companies that do not report their rating results on their websites.

Considering the increasing regulation regarding the disclosure of nonfinancial information and the rising stakeholder interest in CSR, our findings can be useful for many companies to increase the quality and transparency of their ESG reporting.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we employ a theoretical framework and a comprehensive literature review. Section 3 describes our research design. In Section 4, we present our descriptive results, which are verified by an empirical investigation in Section 5. In Section 6, we discuss our results. Finally, conclusions with future research avenues and limitations close the paper.

2. Theoretical Background & Hypotheses Development

For some years now, there have been signs of a trend toward taking more responsibility for the earth and society. Sustainability and responsibility in the case of environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) are increasingly in demand and are no longer just a niche topic. While the terms CSR and ESG are sometimes used interchangeably in the literature, differences can be identified between the two concepts [36,37]. CSR offers an approach that provides general insight into the environmental, social and economic aspects of a company. ESG, on the other hand, addresses the opportunities and risks that result from a company’s CSR approach. Further, ESG provides quantitative information on sustainability efforts, while CSR information comprises of a qualitative nature [37,38]. Consequently, there is a closer connection between CSR and ESG, as the CSR commitment forms the basis for the ESG evaluation parameters [39]. Rather, sustainable ESG responsibility is now regarded as a necessary condition for corporate survival because organizational legitimacy depends on society’s acceptance [40,41].

Therefore, companies need to address sustainability topics in their business models and their reporting to address the ESG information needs of stakeholders, which is in line with the stakeholder accountability approach [16,42,43].

2.1. Stakeholder Accountability Approach

The stakeholder accountability approach emphasizes the importance of taking stakeholder interests into account. In contrast to the shareholder value approach, there is no exclusive focus on economic objectives; in addition, socially relevant criteria must be addressed [44,45]. Accordingly, an essential task of companies is to align the organizational culture and strategic decisions with the stakeholders’ requirements [46] (p. 93), [47]. Due to increasing CSR-oriented concerns of stakeholders, it can be assumed that CSR is an essential prerequisite for successful stakeholder management; therefore, it represents a relevant part of the stakeholder accountability approach [48]. It should be noted that the exclusive consideration of stakeholder interests based on legal claims is not sufficient for not implementing the stakeholder accountability approach [49]. Accordingly, the requirements of the legislator must be compulsorily supplemented by proactive pursuit and implementation of further stakeholder concerns [46] (p. 94). In Germany, significant CSR requirements are currently derived from Directive 2014/95/EU, which obligate capital market-oriented companies with more than 500 employees to report non-financial information. With the planned implementation of the CSRD, the reporting obligation will be extended to non-capital market companies. Following the legal requirements, companies could integrate ESG rating results in the report to provide stakeholders with extra information.

2.2. Legitimacy Theory

Another important theory in the context of CSR reporting derives from the legitimacy theory [50] (p. 58). Legitimacy theory assumes that a company can only exist on the market in the long term if it is given legitimacy by society [51] (p. 292); [52] (p. 192). Legitimacy in this context is understood as a state in which the actions and characteristics of a company correspond to the values and norms of society [53] (p. 572). Within the legitimacy theory, the existence of a social contract between companies and society—from which explicit requirements of the legislator and implicit requirements of society for companies arise—is assumed [54] (p. 1064); [55] (p. 577); [56] (p. 2). Consequently, in addition to law-abiding behavior, an elementary task is to identify and consider society’s implicit requirements. Against the background of the threat of climate change and the increase in social inequality, the demand for an ecologically and socially responsible corporate orientation is becoming greater [57] (p. V); [30] (p. 4611). Thus, CSR represents an essential component for achieving or maintaining legitimacy. For CSR efforts to become visible to society, and thus actually contribute to the attainment of legitimacy, companies must communicate transparently to the outside world [51] (p. 292); [58]; [59] (p. 281). The integration of objective ESG rating results can be an important and useful mean to achieve social acceptance, as it can provide evidence for strong CSR efforts and increase the transparency of the companies. In the literature, legitimacy theory is often extended by aspects of signaling theory, as the CSR report might serve as a signaling tool to provide voluntary information about CSR efforts and CSR achievements [50,60]. From this perspective, companies with strong CSR performance try to signal their CSR achievements by the voluntary provision of additional information, whereas companies with weak CSR performance limit themselves to mandatory disclosures [61,62].

According to these theories, sustainability reporting and ESG rating results are possible ways to signal and maintain the legitimacy of a company and meet the information needs of all stakeholders. Therefore, companies and stakeholders can benefit from transparent nonfinancial corporate reporting [63,64].

2.3. Literature Review

In this context, various studies examine the relationship between CSR performance and financial performance to identify a positive relationship [18,65,66,67,68,69,70]. Another stream of literature has assessed the influence of CSR performance on corporate reputation and indicated a positive relationship [8,9,17,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73]. Therefore, there is a consensus that both stakeholder groups have a great interest in sustainability-related information [29]. While there is general agreement on the relationship between good CSR performance and financial performance and good CSR performance and corporate reputation, there are heterogeneous results regarding the effect of sustainability reporting [19]. In the capital market, investors are showing increasing interest in corporate sustainability and sustainability reporting, as strong CSR performance is an increasingly relevant investment criterion for many stakeholders [3]. In this context, studies have also shown that a strong sustainability report can positively impact financial performance [19,27,74]. Further studies have examined the direct effect of sustainability reporting on investors and recognized that investors attach great importance to nonfinancial reporting in their decision-making process [7,75,76]. Moreover, Chrzan and Pott (2021) concluded from previous studies that a sustainability report can positively impact investor relations and thus influence financial performance [28]. Furthermore, in an experimental study, the above authors found that investors perceive supplementary (taxonomy-aligned) environmental information in reporting positively and, thus, trustworthiness can be increased, regardless of content [28].

Regarding the effect of sustainability reporting on corporate reputation, Pham/Tran (2020) and Odriozola/Baraibar (2017) showed that the disclosure of CSR measures has a positive effect on corporate reputation, whereas Pérez-Cornejo et al. (2020) investigated the indirect effect of reporting in general on corporate reputation [18,19,77]. Thus, the above authors assumed that in addition to external factors (such as the corporate environment), internal factors could also influence the intensity of the relationship between good CSR performance and reputation [77]. Furthermore, they found a positive effect of a high-quality CSR report on the relationship between good CSR performance and corporate reputation. Miras-Rodríguez et al. (2020) pointed out that in contrast, sustainability reporting can have negative effects on corporate reputation in cases of moderate CSR performance [17]. In such cases, sustainability reports are perceived by stakeholders as a purely strategic measure to highlight the positive aspects of sustainability performance, even though actual CSR commitment needs improvement [78]. Axjonow et al. (2018) even found that the preparation of CSR reports does not lead to an immediate increase in reputation [35]. These findings are consistent with the results of the study by Axjonow et al. (2016), which also found no causal relationship between CSR reporting and corporate reputation on the part of non-professional stakeholders in the US [79]. Moreover, Banke and Pott (2022) examined the significance of a sustainability report and assumed a low benefit for non-professional stakeholders due to the scope [80]. Maniora (2013) argued that due to the extraordinary scope of CSR reports, addressees could hardly grasp and evaluate the content [34]. Furthermore, there is a lack of objective comparability of the communicated CSR performance [34]. Although financial performance can be positively influenced by strong CSR performance and high-quality CSR reports, this weakness seems to significantly reduce the motivation of stakeholders to read a sustainability report, especially non-professional stakeholders.

As an alternative or supplement to sustainability reporting, important information on corporate sustainability can be obtained from the results of ESG rating agencies. In particular, professional stakeholders use the results of ratings and take them into account while making investment decisions [81]. Furthermore, several studies have found that companies with strong ESG rating results have shown higher stock returns in the U.S. market during the COVID-19 crisis than weakly rated companies [82,83,84]. This correlation has been confirmed by Engelhardt et al. (2021) for European companies [85]. While these results refer specifically to the effect of ESG rating results in times of crisis, similar effects have been found in Refinitiv’s study, which shows that well-rated companies have better stock performance than do poorly rated companies [86]. Beyond the results of Albuquerque et al. (2020) and Engelhardt et al. (2021), Refinitiv noted that the correlation is independent of a crisis [83,85,86]. Moreover, Signori et al. (2021) confirmed in their study that investors especially use ESG ratings to evaluate companies [82]. However, at the same time, the above study criticized the fact that ESG ratings are predominantly related to financial performance and thus focus only on the relationship with professional stakeholders. Furthermore, only a few studies have examined the effect of ESG rating results on non-professional stakeholders.

Even though investors use ESG rating results, it is evident that more than one rating result should be used for a sufficient assessment due to a large number of disagreements among rating agencies [87]. Stakeholders, therefore, need to invest time in comparing rating results between rating agencies to obtain an adequate overall impression of the results.

This brief literature review shows that sustainability reports and ESG ratings can provide useful information as a potential source of information, but both sources of information have drawbacks. Conceivably, the problems presented can be solved by combining the two information sources, for example by integrating rating results from the most important rating agencies into sustainability reporting.

2.4. Hypothesis Development

Concerning the stakeholder theory, we assume that CSR reports going beyond the legal requirements can serve to fully satisfy the interests of stakeholders. The integration of ESG rating results into the report fulfills this criterion as it complements statutory objectives and measures with CSR assessments. Furthermore, studies show that ESG rating results are a helpful tool for many stakeholders to obtain an impression of the company’s CSR [81]; thus, the integration of ESG ratings is of interest to stakeholders. Prior research thus supports the assumption that companies are interested in integrating ESG rating results. In combination with the legitimacy theory, however, we assume that the integration of negative results could be harmful to the company, as weak results suggest a violation of social contracts. This is consistent with the signaling theory, according to which companies voluntarily report only information about good performance. Therefore, we state the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Companies that integrate ESG rating results into their reporting only consider results of sustainability rating agencies where they have achieved a high rating.

Prior research indicates that stakeholder value comprehensive CSR information. For example, Signori et al. (2021) and Refinitiv (2021) identify that additional information influences stakeholder perceptions [81,86]. This is also in line with legitimacy theory, as the additional information indicates that the social contract is being adhered to. However, this assumption only applies if the additional information is regarded as strong. Supplementary information that indicates weak CSR behavior could negatively impact stakeholders [17]. Therefore, we state the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

Integrating (only) strong ESG rating results in business and sustainability reports positively impact investors.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

Integrating strong and weak ESG rating results in business and sustainability reports negatively impacts investors.

Based on the literature, we assume that non-professional stakeholders tend not to read annual sustainability reports due to time restrictions (e.g., Maniora 2013) or insufficient ability to process and evaluate this information [33,34]. Instead, non-professional stakeholders use low-threshold information offers to satisfy their need for information about companies. We suppose that the company’s website is a suitable information channel for society; thus, we state the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a (H3a).

Integrating strong ESG assessment results in business and sustainability reports has a low impact on non-professional stakeholders.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b).

Communicating strong ESG assessment results on the website positively impacts non-professional stakeholders.

3. Sample Selection and Data Description

In our study on the impact of ESG ratings in corporate reporting on market participants, we focus on DAX40 companies because they are the leading German companies that have a pioneering function in terms of sustainability. Additionally, most DAX40 companies have been committed to ESG beyond legal requirements for many years. Moreover, they are rated by nearly all relevant rating agencies due to their size, sales strength, and importance to the German economy. DAX40 ESG ratings are hand-collected data from companies annual and sustainability reports for 2020.

3.1. ESG Ratings

Generally, ESG ratings of companies serve to inform stakeholders and support them in making decisions regarding sustainable financial products. Ratings also offer great benefits for the rated companies. Moreover, the information highlights the potential for improvement, and problems in the environmental, social and corporate governance areas can be identified at an early stage. Comparability, especially within industries, further advances sustainable development. Companies with good sustainability performance can gain advantages, and a good rating sends positive signals to shareholders and other stakeholders. However, the design options for sustainability ratings are diverse. They differ, for example, in terms of data sources, the selection of rating criteria or the generation of the final score. Rating agencies essentially use four different approaches to select rating criteria to rate companies. Distinctions are made among negative criteria, positive criteria, the best-in-class approach, and rating by risk. In addition to rating criteria, companies are often rated based on risks. Companies face various social, environmental, and entrepreneurial risks depending on their industry, business model and products or services. The greater these risks are, the more consciously these companies must be managed [88]. Since all the assessment approaches presented have their advantages and disadvantages, a combination of these approaches is often used in practice [88]. The market for sustainability rating agencies has changed significantly in recent years. The financial markets focus on economic risk-based financial products results in the growing demand for ESG information; thus, there is now a wide range of ESG company ratings available. Moreover, many small providers of sustainability services have merged with large agencies. Additionally, traditional rating agencies of financial market information also select more information on ESG data and add ESG rating criteria to their models [16]. However, this variety of providers means that investors need to be aware of the multitude of sustainability rating providers and their respective underlying valuation models to make an efficient investment decision while weighing individual ESG preferences. Companies can contribute to greater transparency by publishing the rating results in their annual reports and pointing out the differences in the weighting of the criteria and different methods. We check whether and to what extent they do so, and we hand collect not only the information provided in annual and sustainability reports, but also the DAX40 rating results provided by rating agencies on their website to verify the information provided by the companies and/or add missing ratings.

3.2. Financial Performance

We use financial performance as a measure of the effect on professional stakeholders (investors) and corporate reputation as an indicator of the impact on non-financial stakeholders (consumers) to examine the impact of ESG ratings on stakeholders. For some years, stakeholders have been placing increasing emphasis on ESG aspects while selecting their potential investments [89,90]. In addition to financial aspects, their investment decisions are also influenced by nonfinancial information. Professional stakeholders, in particular, influence the development of the share price through their investment decisions. Therefore, the use of share price values as a measure of the impact on investors seems particularly suitable for our study, as market value is significantly influenced by the investors’ perceptions of the company [91,92]. We take monthly share price values from the database provider Refinitv, starting in the second quarter of 2021. We focus on share price values from 12 periods after the publication of the 2020 annual and sustainability reports. Therefore, we receive 480 company month observations for our investigation.

3.3. Corporate Reputation

We follow Waddock/Googins (2011) and Fombrun/Shanley (1990) and use corporate reputation as an indicator of the effect on consumers to determine the impact of ESG ratings on non-professional stakeholders [93,94]. In this way, corporate reputation reflects stakeholders’ assessment of the extent to which a company meets the expectations of its stakeholders [93,94]. Following Axjonow et al. (2016), we use YouGov’s BrandIndex to measure the perception of the corporate reputation of non-professional stakeholders [79]. BrandIndex is based on perceptions of non-professional stakeholders from thousands of consumer interviews across more than fifty-five markets, consisting of 15 metrics. We focus on the metric of brand reputation, as a good reputation represents a significant target for companies and forms one of the most important intangible assets [95]. For our investigation, we select the reputation scores of brands that match the company names of DAX40 companies. In addition, we add reputation scores of the most common brands of DAX40 companies, whose company names are not the same as their brand names; e.g., for the company Henkel, we used the brand Persil, and for the company Bayer, we chose their most common brand, Aspirin. Following this approach leaves us with reputation scores for 18 of the DAX40 companies. We use the YouGov net reputation score by month for 12 months after the annual and sustainability reports are published, beginning on 1 April 2021. Therefore, we receive 216 observations for our investigation.

4. Descriptive Results

Companies can make it easier for their stakeholders to obtain information by already including the rating results of the most relevant agencies in their reports and highlighting any differences in the rating models that lead to divergent rating results. The following analysis aims to examine the effects of disclosing ESG rating results in corporate reporting on professional stakeholders (investors) and non-professional stakeholders (i.e., consumers).

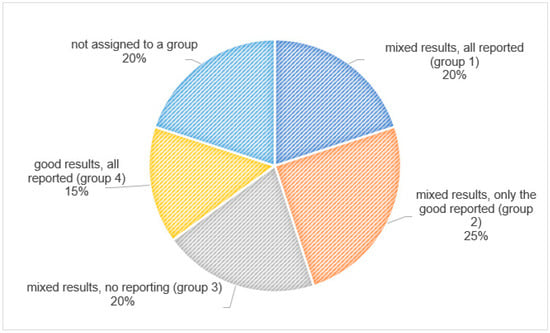

Therefore, addressing Q1 (whether ESG rating results are integrated into the annual and sustainability reports of companies), we evaluate in the first step which rating agencies are most frequently used by companies in their annual and sustainability reports and whether deviating rating results can be explained. For this purpose, we hand-collect ESG rating data from the annual and sustainability reports of DAX40 companies and from the most mentioned three rating agencies that provide their ratings on their official websites. In the next step, we group DAX40 companies according to their ESG rating results and their transparency in reporting the results into the following four groups:

- Group 1: companies with mixed rating results, which are all integrated into their annual or sustainability reports

- Group 2: companies with mixed rating results but only the good result(s) are integrated into their annual or sustainability reports

- Group 3: companies with mixed rating results, which are not integrated into their annual or sustainability reports

- Group 4: companies with strong rating results only, which are all integrated into their annual or sustainability reports

Seven companies cannot be assigned to one of these groups. Therefore, our sample contains n = 33 companies with 12 observations each, which are distributed among the groups as shown in Table 1:

Table 1.

Number of companies in the sample by the availability of dependent and independent variables.

4.1. ESG Rating Results

Regarding Q1. (whether ESG rating results are disclosed in the annual and sustainability reports of companies), we identify the four most relevant rating agencies that are mentioned in German corporate sustainability and annual reports of DAX40 companies:

CDP [24x], MSCI [16x], ISS-oekom [16x], and Sustainalytics [14x]. We crosscheck the reported corporate rating results with the publicly available results from the websites of CDP, MSCI, and Sustainalytics. Consequently, 37 and 39 of the DAX40 companies are rated by CDP and Sustainalytics and MSCI, respectively. We exclude ratings by ISS-oekom from our investigation since these ratings are not publicly available; thus, we cannot verify the reported corporate rating results.

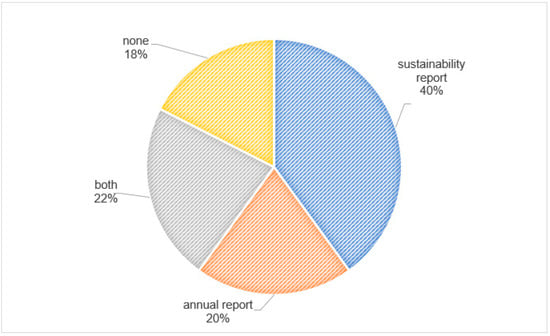

Our survey shows that 82.5% of DAX40 companies (33 companies) report that they have a sustainability rating. A total of 24.24% of them (8 of 33 DAX40 companies) report on their sustainability rating in the annual report, while 48.48% of them (16 of 33 DAX40 companies) report on their sustainability ratings in the sustainability report. A total of 27.27% of reporting companies (9 of 33 DAX40 companies) communicate sustainability ratings in both annual and sustainability reports. A total of 17.5% of DAX40 companies (seven companies) do not report any sustainability rating result, even though 15% (six companies) are rated by rating agencies.

Figure 1 illustrates where DAX40 companies report their sustainability ratings. The majority of these companies (40%) report their sustainability ratings exclusively in their sustainability reports; while 20% report this information exclusively in their annual reports, 22.5% communicate this information in both reports. The remaining 17.5% of companies do not communicate their sustainability ratings, even though sustainability ratings are available for most of them (15%).

Figure 1.

Sustainability rating information in corporate reporting.

In accordance with the literature, our data collection reveals considerably varying ESG rating results depending on the rating agency. An example of this is the sustainability rating of RWE AG. While the company receives a strong ‘A’ rating by MSCI, the Sustainalytics rating ‘high risk’ is in the weaker range. However, CDP rates RWE AG ‘B’ in climate protection and ‘B-’ in water, placing the company in the middle of the scale. Similar differences are achieved in the sustainability ratings of Volkswagen AG. While the company attains one of the higher ratings, with an ‘A-’ rating from CDP, MSCI assigns a ‘CCC’ rating, which corresponds to the worst possible rating and Sustainalytics rates Volkswagen AG’s sustainability performance in the medium risk range. Therefore, the collected data provides evidence of the existence of different rating models and the data basis of ESG rating agencies, as suggested in the literature. Furthermore, our data show that even large variances in ESG rating results are communicated very differently by the concerned companies. While RWE, for example, reports on all three results, Volkswagen mentions only the good CDP result in its annual and sustainability report (i.e., cherry picking).

Additionally, we observe differences in the reporting strategy of companies that have received similar ratings from rating agencies. Companies are divided into four groups to identify the effects of the different integrations in corporate reporting on stakeholder groups. Group 1 includes companies that have mixed ESG rating results and explicitly integrate all rating results into their annual or sustainability reports. Group 2 comprises companies that have mixed ESG rating results but integrate only the strong results (at least an ‘A’ or a ‘low risk’ result) into their annual or sustainability report. Group 3 contains companies that have mixed ESG rating results and integrate none of the results into their annual or sustainability reports. Finally, Group 4 involves companies with only strong ESG rating results (that receive at least an ‘A’ or a ‘low risk’ result) and explicitly integrates all their results into their annual or sustainability report. Figure 2 shows how the companies can be assigned to the four groups, with eight of the 40 companies not being assigned to any of the four groups.

Figure 2.

Division of DAX40 into groups.

Of the companies, 20% report ESG rating results, even though they have received not only good but mixed ratings. So, we reject Hypothesis 1.

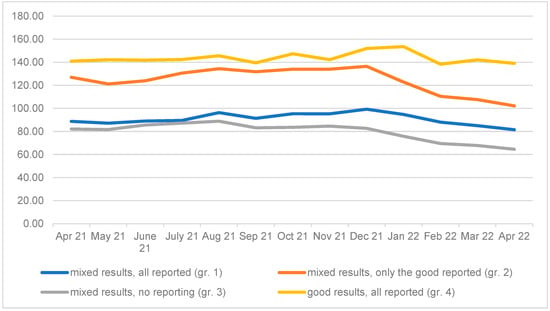

4.2. Impact on Professional Stakeholders

Addressing our second hypothesis about the impact of the integration of ESG rating results in corporate reporting on professional and non-professional stakeholders, our descriptive results indicate that strong ESG rated companies that communicate all their good rating results (Group 4) and companies that communicate only the good ESG rating results in their reporting (Group 2) achieve a higher average share price than the companies that achieve mixed rating results but communicate all results (Group 1) and those, that do not communicate any results (Group 3). These results, in general, confirm that the integration of strong ESG rating results in business and sustainability reports has a positive impact on investors. Figure 3 shows the average stock price development of all four groups of ESG-rated DAX40 companies.

Figure 3.

Average stock prices of ESG-rated DAX 40 companies.

4.3. Impact on Non-Professional Stakeholders

Numerous academic papers have derived a positive relationship between good CSR performance and corporate reputation [8,9,67,68,69]). Based on these studies, we therefore compare the reputation of DAX40 companies concerning their ESG rating results and their reporting of these results. We use the reputation score from YouGov’s BrandIndex to measure the corporate reputation of non-professional stakeholders. Our results show that Group A, predominantly ‘good’ rated companies (with at least an ‘A’ or a ‘low risk’ rating from at least two rating agencies), achieves a mean net reputation score of 16.5 and that Group B, predominantly lower-rated companies (category B; lower or ‘medium risk’ and poorer ratings from at least two rating agencies), generate a mean net reputation score of 14.9. Figure 4 illustrates the average reputation net score of ‘good’ versus ‘below good’ ESG-rated companies.

Figure 4.

Average reputation of ‘good’ versus ‘below good’ ESG-rated DAX40 companies.

The two groups in question differ in their mean reputation scores, as predominantly ‘good’-rated companies achieve a higher mean reputation score than do predominantly lower-rated companies. In accordance with the literature, this observation shows that ESG performance is relevant for consumer behavior, as sustainable companies generally have a better reputation than do poor ESG-performing companies.

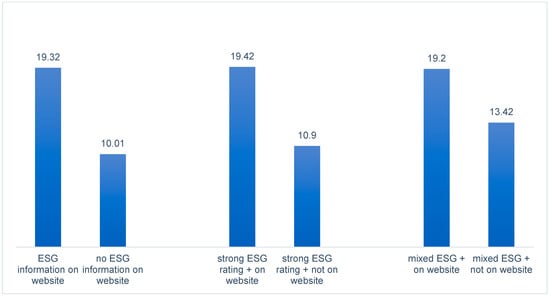

In order to measure the effect of disclosing ESG rating results in corporate reporting on non-professional stakeholders, we consider that they might not read the companies’ annual and sustainability reports due to time restrictions or their insufficient ability to process and evaluate such information [34,35]. Therefore, the literature suggests not using the websites of companies as a common channel for decision-making by non-professional stakeholders [96,97,98]. Thus, we add hand-collected ESG rating information from the websites and press releases of DAX40 companies to our sample of non-professional stakeholders and group the companies according to their disclosure of ESG rating results on their company websites. Figure 5 illustrates the average net reputation scores of DAX40 companies grouped by their reporting of ESG rating information on their websites.

Figure 5.

Reputation of companies (not) communicating ESG rating results on their websites.

A comparison of the mean net reputation values of DAX40 companies indicates that strong ESG-rated companies (receiving at least an ‘A’ or a ‘low risk’ rating from at least two rating agencies) generate a higher reputation from non-professional stakeholders (net reputation score of 19.4 vs. 10.9, respectively) when they communicate these ratings on their websites. These results confirm that the reporting of strong ESG rating results on company websites has a positive impact on non-professional stakeholders. Furthermore, even reporting mixed ESG rating results leads to a higher reputation by non-professional stakeholders compared to no reporting of mixed results (net reputation score of 19.2 vs. 13.42, respectively).

Overall, our descriptive results reveal that the majority of DAX40 companies integrate ESG rating results into their annual or sustainability reports, even if the results are mixed. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is rejected. However, our descriptive results initially indicate that hypotheses 2a, 3a, and 3b can be confirmed. We provide empirical results in the next chapter to finally verify these hypotheses.

5. Empirical Model & Results

In a second step, we empirically investigate our descriptive results and carry out an OLS regression analysis on the impact of ESG performance (1), the impact of reporting ESG ratings (2), and the impact of transparency of ESG rating disclosure (3) in companies reporting on professional and non-professional stakeholders.

We estimate the following model to address Hypotheses 2a, 2b, 3a, and 3b:

In the first step, we evaluate the fundamental influence of ESG performance on investors. Our dependent variable Yi,t is the share price of the company i at the end of the month t as a measure of investors’ behavior. The explanatory variable X1 reflects how sustainable a company is. We conduct X1 by determining the sum of the equally weighted ESG rating results generated by the n = 3 rating agencies (CDP, MSCI and Sustainalytics) based on the previous reporting period t − 1 for each company i. We determine an overall ESG rating score for each company by the cumulated, equally weighted rating scores (each subtracted from 100 before accumulation to facilitate interpretation). A high value of the ESG rating score implies a strong overall rating and vice versa. Further, we control for fixed group effects and fixed time effects. We dispense with the usual control variables for company size, age, and economic strength, as DAX40 is already located exclusively for the largest, capital market-oriented companies with the highest turnover. In all our models we include fixed effects which capture the above-mentioned assignment of a company to one of the four groups.

Model (I) on the fundamental impact of ESG performance on professional stakeholders is:

We proceed in the same way for nonfinancial stakeholders using the reputation score of YouGov’s BrandIndex as a dependent variable X1 and measure Model (I) on the fundamental impact of ESG performance on non-professional stakeholders (consumers):

In a second step, we investigate the impact of ESG rating disclosure on stakeholders. We rerun Model (I) using the variable ESG reporting as an explanatory variable X2. We measure X2 by weighting each transformed rating score by 1 if the individual score is disclosed in reporting and zero otherwise. The ESG reporting score increases with the degree of disclosure, it indicates how the company presents sustainability to their stakeholders. The cumulated weighted ESG rating scores present our variable X2.

Model (II) on the impact of ESG rating disclosure in companies reporting on professional stakeholders:

We proceed in the same way for nonfinancial stakeholders using the reputation score of YouGov’s BrandIndex as dependent variable Y2 and measuring Model (II) on the fundamental impact of ESG rating disclosure in corporate reporting on non-professional stakeholders (consumers). As consumers in general tend not to read annual or sustainability reports, we further add a dummy variable Homepage that captures if a company discloses ESG rating results on their websites or not:

In a third step, we investigate the impact of transparency of reporting on stakeholders. We rerun our model using a linear transformation of X1 and X2 as explanatory variable X3 (= X1 − X2)of Model (III) and run the following OLS regression for the impact of transparency in reporting on professional stakeholders:

We measure transparency X3 as the difference between the cumulated ESG rating scores and the cumulated reported ESG rating scores. If a company discloses all its available rating results, the value of X3 = 0; therefore, X3 decreases with the degree of transparency. We proceed in the same way for investigating the impact of transparency on non-financial stakeholders and measuring Model (III) using the reputation score of YouGov’s BrandIndex as a dependent variable Y2.

As non-professional stakeholders might not use annual or sustainability reports for information, we conduct a different transparency measure for our Model (III). We weight the ESG rating results by 1 if they are disclosed on the company’s website and zero otherwise, and then generate the difference between the cumulated ESG ratings and the weighted cumulated ESG ratings. Again, a value of zero indicates high transparency and increasing values of our transparency measure indicate a decreasing level of transparency.

In the last step, we analyze the transparency effect of disclosing ESG rating results on stakeholders by group and rerun Model III by groups 1–4. As the number of observations by the group is too small for regression in the case of non-professional stakeholders, we run our Model IV only for the professional stakeholders in the groups.

Our empirical results confirm the descriptive results mentioned above. Table 2 provides the results of our regression analysis.

Table 2.

Empirical regression results. ** denotes statistical significance at the 5% level, *** denotes statistical significance at the 1% level.

The results of Model I give evidence of a significant fundamental impact of ESG performance on both stakeholder groups. While ESG performance has a significant negative influence on share prices (driven by untabulated group effects), reputation increases significantly with ESG performance, which proves the increasing demand from consumers for sustainability.

The results of Model II show a significant impact of ESG rating disclosure on stakeholders. Reporting ESG rating results lead to higher share prices and higher reputation.

Furthermore, our results highlight the relevance of transparency in reporting for stakeholders. Companies generate a significant positive impact on both investors and consumers when the difference between ESG rating score and ESG reporting score decreases (high reporting transparency), see results of Model III. Additionally, the results of our group-wise analysis (Model IV) support the importance of transparency in reporting for the capital market. Above all, transparent companies that disclose all received rating results (Group 1 and Group 4) generate a significant inverse impact on their share prices. Thus, they achieve a significant positive impact on their share price when the difference between ESG score and reporting score is low, regardless of the initial ESG strength. According to low transparency (Group 3 generates high differences between ESG scores und reporting scores), the impact on non-reporters’ share prices is significantly affected by their fundamental ESG strength. Overall, our empirical results are consistent with the descriptive findings; thus, Hypothesis 2a is supported. Hypothesis 2b, on the other hand, must be rejected because transparency is an important criterion for stakeholders and has a positive effect on stakeholder perception, leading to positive effects for companies reporting mixed results.

Further, our results indicate that the company homepage is an adequate additionally reporting channel for non-professional stakeholders. While including ESG rating results in the annual and sustainability report has a significant but weak impact on non-professional stakeholders, the influence of reporting on the company homepage reveals a significant effect on the reputation of consumers (Model II). These results confirm hypotheses 3a and 3b.

6. Discussion

Our results indicate that ESG performance is an important criterion for stakeholders’ investment decisions. Thus, our results support the literature on the fundamental influence of ESG strength on firm performance. Additionally, we provide evidence on signaling theory, as companies report ESG ratings to achieve higher stock returns and reputation. Furthermore, our results show that companies take advantage of additionally disclosing ESG rating information on their websites, as non-professional stakeholders use low-threshold information channels for decision making. Above all, we show that transparency of reporting has a relevant impact on stakeholders as companies that report all rating results benefit significantly from higher share prices even with mixed rating results, as opposed to selective or nonreporting companies. Therefore, our results emphasize that transparency plays a crucial role in reporting. Share prices of companies not reporting ESG rating results are dependent on their fundamental ESG strength. However, fully transparent reporting companies that report even mixed results gain from transparency through increased share prices. This observation fosters the literature’s view of the importance of the credibility of reporting information and is consistent with the study by Hyousun/Tae (2018), who report that transparency plays a major role in CSR communication for trust building [99]. Investors use business and sustainability reporting as their primary source of information and cherish credibility through transparency. A large amount of information in CSR reports can lead to incomprehension or confusion, even among experienced report users, thus leading to a so-called information overload. Therefore, there is a risk that the report reader is either no longer able to interpret excessively extensive information or is unwilling to completely view the report due to time restrictions [34]. This might lead to communicated results of the rating agencies being given particularly strong weight in decision-making. The additional, more objective information provided by rating agencies thus leads to more credibility of sustainability information, and concomitantly contribute to more transparency in ESG reporting, which, in turn, increases the overall good impression of companies that publish ESG rating results.

However, a wide range of ESG rating results for the same company raises the question of the extent to which a large variance of ESG rating results provides useful information to investors. ESG ratings aim to support investors in their decision making, but mixed results lead stakeholders to search for differences in the underlying assessment of the rating process. The factors included in the rating process and how they are weighted are not transparent. Thus, the weighted factors possibly conflict with the stakeholders’ individual understanding of sustainability. Nevertheless, a low threshold but high level of corporate transparency ensures that society can obtain objective CSR-related information to assess the CSR performance of a company better, even if the high degree of divergence between the various rating agencies remains critical at this point.

7. Conclusions and Limitations

Our findings highlight the advantage for companies to publish good ESG rating results, as it brings higher stock prices and a better reputation to companies with strong ESG rating results. These findings are consistent with important scientific theories such as stakeholder and legitimacy theory. Furthermore, the study shows that even the communication of weaker results can have a positive effect on stakeholders. We argue that, unlike signaling theory, a high level of transparency might signal credibility and willingness to improve CSR actions. In the past, “greenwashing” often had a negative effect on stakeholders; the unsparing presentation of ESG results could now trigger the opposite effect among stakeholders.

Furthermore, the additional CSR information in reports can strengthen the relationship with stakeholders implying implications for management. It may be helpful to describe the potential for improvement to achieve a better result in the future, as it signals a willingness to act. We should also note that increasing CSR regulation (e.g., CSRD) and political actions (e.g., Green Deal) will continue to make CSR a key issue for companies’ reporting. Therefore, it is conceivable that ESG rating results become more attention, so there is a risk that stakeholders might change perceptions due to (poor) ESG rating results from other sources instead of the company.

Finally, our findings allow for the interpretation that sustainable companies that communicate ESG rating results through effective information channels gain from generating transparency through a higher market value and higher reputation. Thereby, corporate ESG transparency fosters sustainability issues in society and self-fulfillment within the company.

Although this study provides insights into the impact of integrating ESG rating results into annual and sustainability reports on professional and non-professional stakeholder groups, it is not free of limitations. First, economically stronger companies may have more financial opportunities than economically weaker companies to promote sustainable topics inside the company. However, by considering only companies from the DAX40, which have the highest turnover in Germany, in our study, we significantly reduce the probability that the companies examined pursue a weak CSR strategy due to a lack of financial opportunities. Second, readers should note that other relevant factors influencing share prices and the reputation of companies are not considered. Thus, the observed share prices and reputation values of the examined companies may also have arisen due to other or additional characteristics such as the financial situation or size of the company. As previous study results allow for the assumption that CSR is an important component of investment decisions and reputation, the argument that CSR does not influence price and reputation value can be eliminated. Nevertheless, the effect may have been distorted during our observation period by disruptive events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Third, the large heterogeneity of indicators is one of the problems that complicate previous research into the relationship between CSR and the financial performance of companies. The research uses stock market-based measures, i.e., stock prices, and accounting measures of operating performance, e.g., earnings per share, to measure financial performance.

For future research, it is relevant to investigate to what extent the effects observed can also be transferred to non-capital-market-oriented companies through the implementation of the CSRD in 2024. Furthermore, it is conceivable that online platform channels, besides the company website, are a more effective medium to communicate ESG rating results. It could be investigated how ESG rating information, communicated by the company on Instagram or Facebook, affects reputation and stock prices.

Author Contributions

Each author has made substantial contributions to this paper: Conceptualization, M.B.; methodology, M.B. and S.L.; formal analysis, M.B. and S.L.; investigation, M.B. and S.L.; resources, C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B. and S.L.; writing—review & editing, C.P.; visualization, M.B. and S.L.; supervision, C.P.; project administration, S.L.; funding acquisition, C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge financial support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and TU Dortmund University within the funding program Open Access Costs.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers of this paper for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Elkington, J. The triple bottom line. In Environmental Management: Readings and Cases, 2nd ed.; Capstone Publishing Limited: Oxford, UK, 1997; pp. 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Altenburger, R. Gesellschaftliche Verantwortung als Innovationsquelle. In CSR Und Innovationsmanagement; Altenburger, R., Ed.; Management-Reihe Corporate Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, R.; Cowton, C.J. The maturing of socially responsible investment: A review of the developing link with corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 52, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, M.; Van Hoom, V.; Lan, D.; Woll, L.; O’Connor, S. Global Sustainable Investment Alliance. Global Sustainable Investment Review. 2020, Volume 2021, pp. 1–31. Available online: https://gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/GSIR-20201.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Habib, R.; White, K.; Hardisty, D.J.; Zhao, J. Shifting consumer behavior to address climate change. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 42, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzetti, M.; Gatti, L.; Seele, P. Firms Talk, Suppliers Walk: Analyzing the Locus of Greenwashing in the Blame Game and Introducing ‘Vicarious Greenwashing’. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 170, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.M.; Green, W.J.; Ko, J.C.W. The Impact of Strategic Relevance and Assurance of Sustainability Indicators on Investors’ Decisions. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2015, 34, 131–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunjra, A.I.; Boubaker, S.; Arunachalam, M.; Mehmood, A. How Does CSR Mediate the Relationship between Culture, Religiosity and Firm Performance? Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 39, 101587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, S.A.; Zhu, B.; Liu, S. Forecast of Biofuel Production and Consumption in Top CO2 Emitting Countries Using a Novel Grey Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 123997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Kühnen, M. Determinants of Sustainability Reporting: A Review of Results, Trends, Theory, and Opportunities in an Expanding Field of Research. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenger, S.; Maniora, J.; Pott, C. Implikationen des CSR-Richtlinie-Umsetzungsgesetzes für den Mittelstand—Empirische Analyse der MDAX-Unternehmen. Die Wirtsch. (WPg) 2019, 72.2019, 779–789. [Google Scholar]

- Velte, P. Does ESG performance have an impact on financial performance? Evidence from Germany. J. Glob. Responsib. 2017, 8, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalet, S.; Kelly, T.F. CSR Rating Agencies: What is Their Global Impact? J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2019, 5822, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billio, M.; Costola, M.; Hristova, I.; Latino, C.; Pelizzon, L. Inside the ESG Ratings: (Dis)Agreement and Performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1426–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escrig-Olmedo, E.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.; Ferrero-Ferrero, I.; Rivera-Lirio, J.; Muñoz-Torres, M. Rating the Raters: Evaluating How ESG Rating Agencies Integrate Sustainability Principles. Sustainability 2019, 11, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miras-Rodríguez, M.d.M.; Bravo-Urquiza, F.; Escobar-Pérez, B. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting Actually Destroy Firm Reputation? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1947–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odriozola, M.D.; Baraibar-Diez, E. Is Corporate Reputation Associated with Quality of CSR Reporting? Evidence from Spain: Quality of CSR Reporting and Corporate Reputation in Spain. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.S.T.; Tran, H.T. CSR Disclosure and Firm Performance: The Mediating Role of Corporate Reputation and Moderating Role of CEO Integrity. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitolla, F.; Raimo, N.; Rubino, M. Board Characteristics and Integrated Reporting Quality: An Agency Theory Perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. 2020, 27, 1152–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egginton, J.F.; McBrayer, G.A. Does It Pay to Be Forthcoming? Evidence from CSR Disclosure and Equity Market Liquidity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverte, C. The Impact of Better Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure on the Cost of Equity Capital: Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and Cost of Capital. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, G.; Sciarelli, M. Towards a more ethical market: The impact of ESG rating on corporate financial performance. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clementino, E.; Perkins, R. How Do Companies Respond to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Ratings? Evidence from Italy. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avramov, D.; Cheng, S.; Lioui, A.; Tarelli, A. Sustainable investing with ESG rating uncertainty. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 145, 642–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, M.; Shiu, Y.; Wang, C. Socially responsible investment returns and news: Evidence from Asia. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1565–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, A.-A.; Chen, L.-N.; Hu, J.-C. A Study of the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility Report and the Stock Market. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrzan, S.; Pott, C. Does the EU Taxonomy for Green Investments affect Investor Judgment? An Experimental Study of Private and Professional German Investors. SSRN J. 2021, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan, E.; Kantur, D.; Maden, C.; Telci, E.E. Investigating the Mediating Role of Corporate Reputation on the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Multiple Stakeholder Outcomes. Qual. Quant. 2016, 50, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mion, G.; Loza Adaui, C.R. Mandatory Nonfinancial Disclosure and Its Consequences on the Sustainability Reporting Quality of Italian and German Companies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hąbek, P.; Wolniak, R. Assessing the quality of corporate social responsibility reports: The case of reporting practices in selected European Union member states. Qual. Quant. 2016, 50, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campopiano, G.; De Massis, A. Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting: A Content Analysis in Family and Non-family Firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 511–534. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24702957 (accessed on 7 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Axjonow, A. The Impact of Financial and Non-Financial Disclosure on Corporate Reputation among Non-Professional Stakeholders. 2017. Available online: https://eldorado.tu-dortmund.de/bitstream/2003/36036/1/Dissertation_Axjonow.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Maniora, J. Der GRI G4 Standard–Synergie oder Antagonismus zum IIRC-Rahmenwerk? Erste empirische Ergebnisse über das Anwendungsverhältnis beider Rahmenwerke. Z. Int. Kap. Rechn. 2013, 10, 479–489. [Google Scholar]

- Axjonow, A.; Ernstberger, J.; Pott, C. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure on Corporate Reputation: A Non-Professional Stakeholder Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. J. Corp. Finance 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollman, E. Corporate Social Responsibility, ESG, and Compliance. Los Angeles Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2019-35. 2019. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3479723 (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Piyush, G. The Evolution of ESG from CSR. Available online: https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=80bbe258-a1df-4d4c-88f0-6b7a2d2cbd6a (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Hiß, S. Globale Finanzmärkte und nachhaltiges Investieren. In Handbuch Umweltsoziologie; VS Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011; pp. 651–670. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jenkins, H. A Critique of Conventional CSR Theory: An SME Perspective. J. Gen. Manag. 2004, 29, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, F.; Tencati, A. Sustainability and Stakeholder Management: The Need for New Corporate Performance Evaluation and Reporting Systems. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, M. The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. N. Y. Times Mag. 1970, 122–124. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/13/archives/a-friedman-doctrine-the-social-responsibility-of-business-is-to.html (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Chen, R. Social and financial stewardship. Account. Rev. 1975, 50, 533–543. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell, O.C.; Gonzalez-Padrom, T.L.; Hult, G.M.T.; Maiganan, I. From market orientation to stakeholder orientation. J. Public Policy Mark. 2010, 29, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; McVea, J. A stakeholder approach to strategic management. SSRN Electron. J. 2001. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=263511 (accessed on 7 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- van Huijstee, M.; Glasbergen, P. The practice of stakeholder dialogue between multinationals and NGOs. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangle, S.; Babu, P.R. Evaluating sustainability practices in terms of stakeholders’ satisfaction. Int. J. Bus. Gov. Ethics 2007, 3, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienaber, A.; Borgstedt, P.; Liesenkötter, B.; Schewe, G. Kommunikation von ökologisch nachhaltiger Unternehmensführung im Energieversorgungssektor—Eine qualitativ-longitudinale Analyse zur Transparenz in der Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung. Z. Umweltpolit. Umweltr. 2015, 1, 54–98. [Google Scholar]

- Deegan, C. Introduction. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Whetten, D. Rethinking the Relationship Between Reputation and Legitimacy: A Social Actor Conceptualization. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2008, 11, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoni, L.; Bini, L.; Bellucci, M. Effects of social, environmental, and institutional factors on sustainability report assurance: Evidence from European countries. Meditari Account. Res. 2020, 28, 1059–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Davey, H.; Eggleton, I.R.C. Towards a comprehensive theoretical framework for voluntary IC disclosure. J. Intellect. Cap. 2011, 12, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danisch, C. The Relationship of CSR Performance and Voluntary CSR Disclosure Extent in the German DAX Indices. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stibbe, R. CSR-Erfolgssteuerung; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri, M.A. Theoretical insights on integrated reporting: The inclusion of non-financial capitals in corporate disclosures. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2018, 23, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P.; Stawanoga, M. Integrated reporting: The current state of empirical research, limitations and future research implications. J. Manag. Control 2017, 28, 275–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, G. The market for ‘lemons’: Quality uncertainty and the market-mechanism. Q. J. Econ. 1970, 84, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrecchia, R. Discretionary disclosure. J. Account. Econ. 1983, 5, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, R.A. Disclosure of non-proprietary information. J. Account. Res. 1985, 23, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackmann, J. Die Auswirkungen der Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung Auf den Kapitalmarkt: Eine Empirische Analyse, 1st ed.; Gabler Research; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hetze, K. Effects on the (CSR) Reputation: CSR Reporting Discussed in the Light of Signalling and Stakeholder Perception Theories. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2016, 19, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Strategic attributions of corporate social responsibility and environmental management: The business case for doing well by doing good! Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, A.; Liang, H.; Renneboog, L. Socially Responsible Firms. SSRN J. 2014, 112, 1507–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Lead to Superior Financial Performance? A Regression Discontinuity Approach. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 2549–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, H.; Li, K.; Ma, Y. Stakeholder Orientation and the Cost of Debt: Evidence from State-Level Adoption of Constituency Statutes. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2021, 56, 1908–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Liang, H.; Zhan, X. Peer Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 5487–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Liang, H.; Ng, L. Socially Responsible Corporate Customers. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 598–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenhoefer, L.M. The impact of CSR on corporate reputation perceptions of the public—A configurational multi-time, multi-source perspective. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2019, 28, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanaland, A.J.S.; Lwin, M.O.; Murphy, P.E. Consumer perceptions of the antecedents and consequences of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D.S. Creating and Capturing Value: Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility, Resource-Based Theory, and Sustainable Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1480–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuy, C.T.M.; Khuong, N.V.; Canh, N.T.; Liem, N.T. Corporate Social responsibility disclosure and financial performance: The mediating role of financial statement comparability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemir, S.; Baccouche, C.; Ayadi, S.D. The Influence of ESG Information on Investment Allocation Decisions: An Experimental Study in an Emerging Country. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2019, 20, 458–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikhardsson, P.; Holm, C. The Effect of Environmental Information on Investment Allocation Decisions—An Experimental Study. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cornejo, C.; Quevedo-Puente, E.; Delgado-García, J.B. Reporting as a Booster of the Corporate Social Performance Effect on Corporate Reputation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1252–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, D.; Boiral, O. The Quality of Sustainability Reports and Impression Management: A Stakeholder Perspective. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2017, 30, 643–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axjonow, A.; Ernstberger, J.; Pott, C. Auswirkungen der CSR-Berichterstattung auf die Unternehmensreputation. UmweltWirtschaftsForum 2016, 24, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banke, M.; Pott, C. Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung im Zuge einer zunehmenden CSR-Regulierung: Auswirkungen auf nicht-kapitalmarktorientierte Unternehmen? Z. Umweltpolit. Umweltr. 2022, 1, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; Velamuri, S.R. A New Approach to CSR—Company Stakeholder Responsibility. In The Routledge Companion to Corporate Social Responsibility; Taylor & Francis Group: Milton, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Signori, S.; San-Jose, L.; Retolaza, J.L.; Rusconi, G. Stakeholder value creation: Comparing ESG and value added in European companies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, R.; Koskinen, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, C. Resiliency of Environmental and Social Stocks: An Analysis of the Exogenous COVID-19 Market Crash. Rev. Corp. Financ. Stud. 2020, 9, 593–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, K.V.; Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. Social Capital, Trust, and Firm Performance: The Value of Corporate Social Responsibility during the Financial Crisis: Social Capital, Trust, and Firm Performance. J. Financ. 2017, 72, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Engelhardt, N.; Ekkenga, J.; Posch, P. ESG Ratings and Stock Performance during the COVID-19 Crisis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refinitiv. Refinitiv MarketPsych ESG Analytics—Quantifying Sustainability in Global News and Social Media. 2021, RE1327580/2-21. Available online: https://resourcehub.refinitiv.com/443870globalsustainablefinanceesg/443870-ESG-PaperMarketPsychSustainability?utm_source=Eloqua&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=443870_2021GlobalSustainableFinanceESG&utm_content=443870_2021GlobalSustainableFinanceESG+Email6MarketPhychQuantAMERSEMEA (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Chatterji, A.K.; Levine, D.I.; Toffel, M.W. How Well Do Social Ratings Actually Measure Corporate Social Responsibility? J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2009, 18, 125–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, S. Die Integration von Nachhaltigkeitsratings in konventionelle Ratings: Wie gelingt das Mainstreaming? In Corporate Social Responsibility auf dem Finanzmarkt; Ulshöfer, G., Bonnet, G., Eds.; Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, A.; Glaum, M.; Kaiser, S. ESG performance and firm value: The moderating role of disclosure. Glob. Financ. J. 2018, 38, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, W.B.; Jackson, K.E.; Peecher, M.E.; White, B.J. The Unintended Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility Performance on Investors’ Estimates of Fundamental Value. Account. Rev. 2014, 89, 275–302. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24468519 (accessed on 7 June 2022). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, B.; Niu, F. Investor Sentiment, Accounting Information and Stock Price: Evidence from China. Pac. -Basin Financ. J. 2016, 38, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jian, X.; Li, L. Does fair value measurement model have value relevance? Empirical evidence from financial assets investigation. China Account. Rev. 2010, 8, 383–398. [Google Scholar]

- Waddock, S.; Googins, B.K. The Paradoxes of Communicating Corporate Social Responsibility. In The Handbook of Communication and Corporate Social Responsibility; Ihlen, Ø., Bartlett, J.L., May, S., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.; Shanley, M. What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.W.; Dowling, G.R. Corporate Reputation and Sustained Superior Financial Performance: Reputation and Persistent Profitability. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saat, R.M.; Selamat, M.H. An examination of consumer’s attitude towards corporate cocial responsibility (CSR) web communication using media richness theory. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 155, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Branco, M.C.; Rodrigues, L.L. Corporate Social Responsibility and Resource-Based Perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]