Residents’ Motivation and Place Meanings in a Hallmark Event: How to Develop a Sustainable Event in the Hosting Destination

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Place Meaning in an Event

2.2. Residents’ Motivation in an Event

2.3. Motivation in the SDT

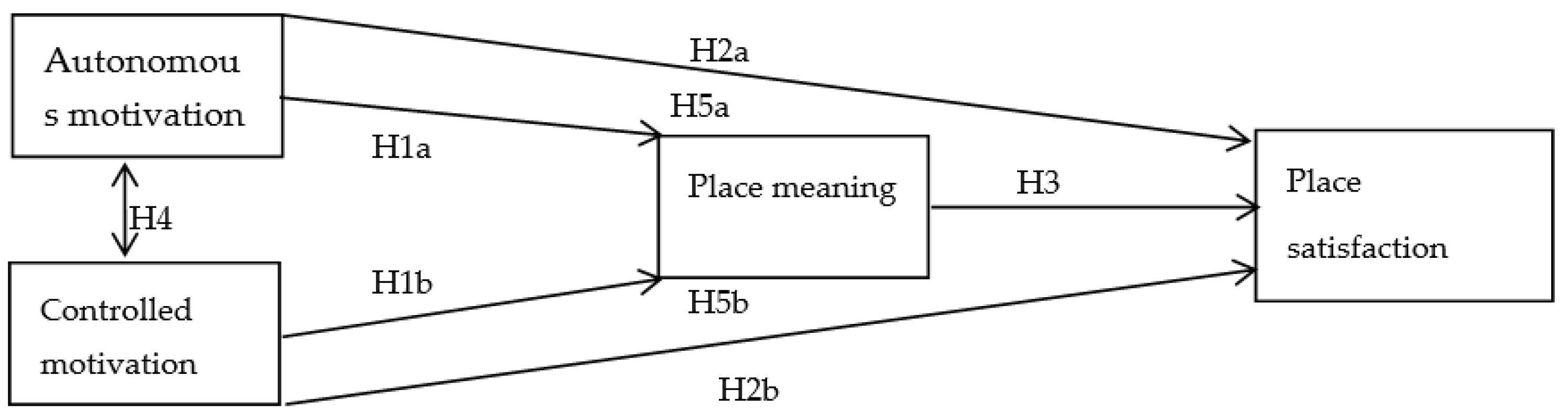

2.4. Research Hypotheses

3. Methodology and Data

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Case

3.3. Study 1

3.3.1. Research Design

3.3.2. Data Collection

3.3.3. Data Analysis

3.4. Study 2

3.4.1. Research Design and Procedure

3.4.2. Data Collection

3.4.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Study 1

4.2. Study 2

4.2.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.2.2. Reliability and Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

4.2.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4.2.4. Testing for Mediation Using SEM Bootstrap Approach

5. Discussion

5.1. Residents’ Place Meaning in PCFLC

5.2. Residents’ Motivation on Place Meaning and Place Satisfaction

5.3. The Mediating Role of Place Meaning in the Relationship between Residents’ Motivation and Place Satisfaction

6. Conclusions

7. Recommendation

8. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hinch, T.; Holt, N.L. Sustaining places and participatory sport tourism events. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1084–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, M.C. For a While They Live a Few Feet Off the Ground. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 2016, 45, 367–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, C.T. Are you being served? The impacts of a tourist hallmark event on the place meanings of residents. Event Manag. 2007, 11, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triste, L.; Vandenabeele, J.; van Winsen, F.; Debruyne, L.; Lauwers, L.; Marchand, F. Exploring participation in a sustainable farming initiative with self-determination theory. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2018, 16, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.R.B. Assessing the Impact of Hallmark Events: Conceptual and Research Issues. J. Travel Res. 1984, 23, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, R.E.; Pearce, D.G. Why do people attend events: A comparative analysis of visitor motivations at four South Island events. J. Travel Res. 2001, 39, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Pion: London, UK, 1976; pp. 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Campelo, A.; Aitken, R.; Thyne, M.; Gnoth, J. Sense of place: The importance for destination branding. J. Travel Res. 2013, 53, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Vansteenkiste, M. Self-determination theory and basic need satisfaction: Understanding human development in positive psychology. Ric. Psicol. 2004, 27, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dedeurwaerdere, T.; Admiraal, J.; Beringer, A.; Bonaiuto, F.; Cicero, L.; Fernandez-Wulff, P.; Hagens, J.; Hiedanp, J.; Knights, P.; Molinario, E. Combining internal and external motivations in multi-actor governance arrangements for biodiversity and ecosystem services. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 58, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kwok, Y.Y.; Chui, W.H.; Wong, L.P. Need satisfaction mechanism linking volunteer motivation and life satisfaction: A mediation study of volunteers subjective well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 1315–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.M.; Williams, K.J.H.; Ford, R.M. Community perceptions of plantation forestry The association between placemeanings and social representations of a contentious rural land use. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynveen, C.J.; Kyle, G.T.; Sutton, S.G. Natural area visitors’ place meaning and place attachment ascribed to a marine setting. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.J.; Wallace, G.N.; Williams, D.R. Place as Relationship Partner: An Alternative Metaphor for Understanding the Quality of Visitor Experience in a Backcountry Setting. Leis. Sci. 2006, 28, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieryn, T.F. A space for place in sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2000, 26, 463–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lau, C.; Li, Y. Analyzing the effects of an urban food festival: A place theory approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.F. Space and place: Humanistic perspective. In Philosophy in Geography; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1979; pp. 387–427. [Google Scholar]

- Stedman, R.C. Is it really just a social construction? The contribution of the physical environment to sense of place. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R. Making sense of ‘place’: Reflections on pluralism and positionality in place research. Landsc. Urban Plan 2014, 131, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufford, M. Thresholds to an alternate realm: Mapping the chaseworld in New Jersey’s Pine Barrens. In Place Attachment; Altman, I., Low, S.M., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 231–252. [Google Scholar]

- Dustin, D.L.; Schneider, I.E.; McAvoy, L.H.; Frakt, A.N. Cross-cultural claims on Devils Tower National Monument: A case study. Leis. Sci. 2002, 24, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, M. American Indians, place meanings and the old/new West. J. Leis. Res. 2004, 34, 383–396. [Google Scholar]

- Guojun, Z.; Shuzhi, S.; Hong, Z.; Bo, L.; Xiaomei, C. Food culture production behind globalization and place conflicts—A case study of Guangzhou. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 33, 291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Bricker, K.S.; Kerstetter, D. An interpretation of special place meanings whitewater recreationists attach to the South Fork of the American River. Tour. Geogr. 2002, 4, 396–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M. The relationship between tourist motivations and the interpretation of place meanings. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowall, S. A comparison between Thai residents and non-residents in their motivations, performance evaluations, and overall satisfaction with a domestic festival. J. Vacat. Mark. 2010, 10, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Kozak, M.; Ferradeira, J. From tourist motivations to tourist satisfaction. Int. J. Cult. Hosp. Res. 2013, 7, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báez, A.; Devesa-Fernández, M. Motivation, satisfaction and loyalty in the case of a film festival: Differences between local and non-local participants. J. Cult. Econ. 2017, 41, 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeng, H.Y.; Jang, H.Y.; Li, J.M. A critical review of the motivational factors for festival attendance based on meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 17, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Gibson, H.; Sisson, L. The loyalty process of residents and tourists in the festival context. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H.E.; Daniels, M.J. Does the music matter? Motivations for attending a music festival. Event Manag. 2005, 9, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Sun, J.; Mahoney, E. Roles of Motivation and Activity Factors in Predicting Satisfaction: Exploring the Korean Cultural Festival Market. Tour. Anal. 2008, 13, 413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, W.; Zhao, W. Determinants of Arts Festival Participation: An Investigation of Macao Residents. Event Manag. 2012, 16, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.J.; Thompson, M. Self determination theory and the wine club attribute formation process. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 561–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.; Ryan, R.M. When helping helps: Autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.; Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Motivation, meaning, and wellness: A Self-determination perspective on the creation and internalization of personal meanings and life goals. In The Human Quest for Meaning Theories, Research, and Applications; Wong, P.T.P., Ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. To be happy or to be self-fulfilled: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. In Annual Review of Psychology; Fiske, S., Ed.; Annual Reviews: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2001; Volume 52, pp. 141–166. [Google Scholar]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Aelterman, N.; De Muynck, G.; Haerens, L.; Patall, E.; Reeve, J. Fostering Personal Meaning and Self-relevance: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective on Internalization. J. Exp. Educ. 2018, 86, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Olafsen, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, M.H.; Crocker, P.R.; Peter, R.E. Testing Self-Determined Motivation as a Mediator of the Relationship Between Psychological Needs and Affective and Behavioral Outcomes. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 645–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, Y.; Li, C. Helping others helps? A self-determination theory approach on work climate and wellbeing among volunteers. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2018, 14, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Holmes, M.; Novotny, M. Because I believe in it: Examining intrinsic and extrinsic motivations for sustainability in festivals through self-determination theory. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 47, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Geus, S.; Toepoel, G.; Richards, V. The Dutch Queen’s Day event: How subjective experience mediates the relationship between motivation and satisfaction. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2013, 4, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Masso, A.; Dixon, J.; Hernández, B. Place Attachment, Sense of Belonging and theMicro-Politics of Place Satisfaction. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology and Quality of Life Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Stedman, R. Toward a social psychology of place: Predicting behavior from place-based cognitions, attitude, and identity. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Bo, L. Concepts analysis and research implications: Sense of place, place attachment and place identity. J. South China Norm. Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2011, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hesari, E.; Peysokhan, M.; Havashemi, A.; Gheibi, D.; Ghafourian, M.; Bayat, F. Analyzing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationship with residential satisfaction in new cities: The case of Sadra, Iran. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 142, 1031–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmetyinen, A.; Dimitrovski, D.; Nieminen, L.; Pohjola, T. Cruise destination brand awareness as a moderator in motivation-satisfaction relation. Tour. Rev. 2016, 71, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukergin, K.G.; Gürlek, M. ‘What if this is my last chance?’: Developing a last-chance tourism motivation model. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, J.Y.Y.; Ntoumanis, N.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Duda, J.L.; Williams, G.C. Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: A meta-analysis. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 7, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amérigo, M.; Aragonés, J.I. A theoretical and methodological approach to the study of residential satisfaction. J. Environ. Psychol. 1997, 17, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Elliot, A.J. Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal weil-being: The self-concordance Model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, S.J. The relationship between teacher autonomous support and high school students’ self-motivation and basic psychological needs. J. Southwest China Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 41, 141–145. [Google Scholar]

- King, L.A.; Hicks, J.A.; Krull, J.; Del Gaiso, A.K. Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, Z. A Study on Characteristics of Tourist Tourism Motivation in Forest Park Based on Self-Determination Theory; MA Type; Central South University of Forestry and Technology: Changsha, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oostlander, J.; Güntert, S.; Wehner, T. Linking autonomy-supportive leadership to volunteer satisfaction: A self-determination theory perspective. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2014, 25, 1368–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z. Sustained participation in virtual communities from a Self-Determination perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6347. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo, L.C. For better or worse: Exploring multiple dimensions of place meaning. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. The Influence of Academic Autonomous Motivation on Learning Engagement and Life Satisfaction in Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction. J. Educ. Learn. 2018, 7, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyd, N. The 39th China Luoyang Peony Culture Festival Ended Successfully. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1699621629937271529&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- Yin, R. Case Study Research, 4th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, J.W.; Davenport, M.A.; Anderson, D.H.; Leahy, J.E. Place meanings and desired management outcomes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 101, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Smith, L.D.G.; Weiler, B. Relationships between place attachment, place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviour in an Australian national park. J. Sustain. Tour 2013, 21, 434–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.L.; Gillaspy, J.A.; Purc-Stephenson, R. Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: A review and some recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2009, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 112–117. [Google Scholar]

- Bongomin, G.O.C.; Munene, J.C.; Ntayi, J.M.; Malinga, C.A. Collective action among rural poor Does it enhance financial intermediation by banks for financial inclusion in developing economies? Int. J. Bank Mark. 2018, 37, 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator—Mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.; Black, B.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice-Hall International: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhonglin, W.; Baojuan, Y. Mediating effect analysis: Method and model development. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, M.A.; Anderson, D.H. Getting from Sense of Place to Place-Based Management: An Interpretive Investigation of Place Meanings and Perceptions of Landscape Change. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2005, 18, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K.; Kaminoff, R. Place identity: Physical world socialization of the self. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kil, N.; Holland, S.M.; Stein, T.V. Place meanings and participatory planning intentions. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2014, 27, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greider, T.; Garkovich, L. Landscapes: The social construction of nature and the environment. Rural Sociol. 1994, 59, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Jun-Xi, Q.; Xiao-Liang, C. Place and identity: The rethink of place of European-American Human Geography. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 25, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Twigger-Ross, C.L.; Uzzell, D.L. Place and identity processes. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S. Symbolic ties that bind: Place attachment in the plaza. In Place Attachment; Low, S., Altman, I., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Arch, W.G. Tourism Sensemaking; Strategies to Give Meaning to Experience; Ringgold, Inc.: Portland, OR, USA, 2011; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 2008, 3, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrd, P.P.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The relation of intrinsic need satisfaction to performance and well-being in two work settings. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 2045–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, M. Residential attachment: Sources of residential and community satisfaction. J. Soc. Issues 1982, 38, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant Number | Age | Sex | Educational Level | Length of Residence in Luoyang | Number of Participation Times in PCFLC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 23 | Female | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| P2 | 23 | Male | 3 | >15 | 1 |

| P3 | 62 | Female | 1 | >15 | 5 |

| P4 | 45 | Female | 1 | >15 | >10 |

| P5 | 21 | Male | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| P6 | 21 | Male | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| P7 | 46 | Male | 2 | >15 | >5 |

| P8 | 24 | Female | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| P9 | 44 | Female | 4 | >15 | >10 |

| P10 | 48 | Male | 2 | >15 | >5 |

| P11 | 37 | Female | 4 | 10 | >5 |

| P12 | 36 | Female | 4 | >15 | 1 |

| P13 | 65 | Male | 4 | >15 | >5 |

| P14 | 32 | Male | 2 | >15 | 3 |

| P15 | 39 | Male | 4 | 13 | 2 |

| P16 | 36 | Male | 4 | >15 | 4 |

| P17 | 38 | Female | 4 | >15 | >5 |

| P18 | 42 | Male | 4 | >15 | >10 |

| P19 | 36 | Male | 4 | 14 | 3 |

| P20 | 28 | Female | 2 | >15 | >5 |

| P21 | 27 | Female | 4 | >15 | 3 |

| Thematic Nodes | Semantic Codes | Frequency | Total | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic dependency | Increase economic income | 43 | 82 | 24.26 |

| Provide job opportunities | 24 | |||

| Promote the development of related industries | 15 | |||

| Leisure | Enrich hallmark event life | 28 | 125 | 36.98 |

| Strengthen the family ties | 35 | |||

| Strengthen social relations | 38 | |||

| Aesthetic | 10 | |||

| entertainment | 14 | |||

| Self-development | Perfect or optimize the world outlook | 18 | 36 | 10.65 |

| Make a personal breakthrough | 11 | |||

| Improve one’s ability | 7 | |||

| Self-identification | Represent part of me | 8 | 95 | 28.11 |

| Have a sense of pride | 36 | |||

| Be important in PCFLC | 12 | |||

| Be attached to the place | 25 | |||

| Be attached to the community | 14 |

| Item | Item Description | Factor Loading | Factor Mean Value | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous motivation | 4.009 | 0.670 | 0.909 | ||

| MA1 | This is part of my life. | 0.962 | |||

| MA2 | I want to get a sense of accomplishment by doing this. | 0.772 | |||

| MA3 | I am interested in the festival. | 0.819 | |||

| MA4 | I want to achieve specific goals. | 0.668 | |||

| MA5 | I want to have fun by doing this | 0.844 | |||

| Controlled motivation. | 3.724 | 0.609 | 0.820 | ||

| MC1 | I will be upset if I don’t do that. | 0.805 | |||

| MC2 | I am influenced by external factors. | 0.611 | |||

| MC3 | I am mainly for economic necessities. | 0.898 | |||

| Leisure | 3.151 | 0.628 | 0.892 | ||

| LI1 | It’s relaxing for me. | 0.772 | |||

| LI2 | It enriches my hallmark event life. | 0.681 | |||

| LI3 | It provides a chance to socialize with friends and other contacts. | 0.907 | |||

| LI4 | It’s an aesthetic activity. | 0.651 | |||

| LI5 | It ties the generations of my family together. | 0.912 | |||

| Economic dependence | 4.117 | 0.684 | 0.869 | ||

| ED1 | The festival increases the incomes of residents. | 0.714 | |||

| ED2 | The festival supplies more jobs for us. | 0.781 | |||

| ED3 | The festival promotes the development of related industries. | 0.966 | |||

| Self-identity | 3.675 | 0.571 | 0.863 | ||

| SI1 | I am proud of holding the festival in Luoyang. | 0.957 | |||

| SI2 | Attending the festival reflects a part of me. | 0.682 | |||

| SI3 | I feel like part of my community. | 0.896 | |||

| SI4 | I make a very positive contribution to the success of the event. | 0.456 | |||

| SI5 | I feel like part of the place. | 0.683 | |||

| Self-development | 3.222 | 0.596 | 0.741 | ||

| SD1 | The festival promotes my abilities. | 0.633 | |||

| SD2 | The festival optimizes my worldview. | 0.889 | |||

| Place satisfaction | 3.567 | 0.629 | 0.835 | ||

| PS1 | I believe I did the right thing in PCFLC. | 0.728 | |||

| PS2 | I am satisfied with my experience in PCFLC. | 0.751 | |||

| PS3 | I am happy about my decision to PCFLC. | 0.891 |

| Non-Mediated Model | Mediated Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled motivation → Place meaning | Not estimated | −0.322 *** |

| Autonomous motivation → Place meaning | Not estimated | 0.334 *** |

| Place meaning → Place satisfaction | 0.404 *** | 0.445 *** |

| Controlled motivation → Place satisfaction | 0.033 | −0.056 *** |

| Autonomous motivation → Place satisfaction | 0.242 *** | 0.329 *** |

| χ2 | 412.932 | 316.036 |

| DF | 86 | 84 |

| CMIN/DF | 4.802 | 3.762 |

| Probability | 0 | 0 |

| IFI | 0.904 | 0.932 |

| TLI | 0.882 | 0.914 |

| NFI | 0.882 | 0.909 |

| CFI | 0.903 | 0.931 |

| RMSEA | 0.089 | 0.075 |

| Standard Total Effects | Controlled Motivation | Autonomous Motivation | Place Meaning | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place meaning | −0.322 *** | 0.334 *** | 0 | ||

| Place Satisfaction | −0.056 *** | 0.329 *** | 0.445 *** | ||

| Standard direct effects | Controlled motivation | Autonomous motivation | Place meaning | ||

| Place meaning | −0.322 *** | 0.334 *** | 0 | ||

| Place satisfaction | 0.088 | 0.18 ** | 0.445 *** | ||

| Standard indirect effects | Controlled motivation | Autonomous motivation | Place meaning | ||

| Place meaning | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0 | ||

| Place satisfaction | −0.143 *** | 0.148 *** | 0 | ||

| Bootstrap mediation results | Point estimates | Standard error | Lower bound | Upper bound | p |

| Controlled motivation → Place satisfaction | −0.143 | 0.051 | −0.266 | −0.064 | 0 |

| Autonomous motivation → Place satisfaction | 0.148 | 0.045 | 0.078 | 0.259 | 0 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Path Coefficients | T-Value | p Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1b | CM → PM | −0.322 | −5.466 | *** | supported |

| H1a | AM → PM | 0.334 | 5.708 | *** | supported |

| H3 | PM →PS | 0.445 | 5.107 | *** | supported |

| H2b | CM → PS | 0.088 | 1.424 | 0.154 | unsupported |

| H2a | AM →PS | 0.18 | 3.162 | 0.002 | supported |

| H4 | AM ↔ CM | −0.344 | −6.322 | 0 | supported |

| H5b | CM → PM → PS | −0.143 | 1.856 | *** | supported |

| H5a | AM →PM → PS | 0.148 | 6.736 | *** | supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Wu, S.; Sun, H. Residents’ Motivation and Place Meanings in a Hallmark Event: How to Develop a Sustainable Event in the Hosting Destination. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159526

Zhang J, Wu S, Sun H. Residents’ Motivation and Place Meanings in a Hallmark Event: How to Develop a Sustainable Event in the Hosting Destination. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159526

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jie, Shaofeng Wu, and Huan Sun. 2022. "Residents’ Motivation and Place Meanings in a Hallmark Event: How to Develop a Sustainable Event in the Hosting Destination" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159526

APA StyleZhang, J., Wu, S., & Sun, H. (2022). Residents’ Motivation and Place Meanings in a Hallmark Event: How to Develop a Sustainable Event in the Hosting Destination. Sustainability, 14(15), 9526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159526