Examining the Factors Influencing Tourists’ Destination: A Case of Nanhai Movie Theme Park in China

Abstract

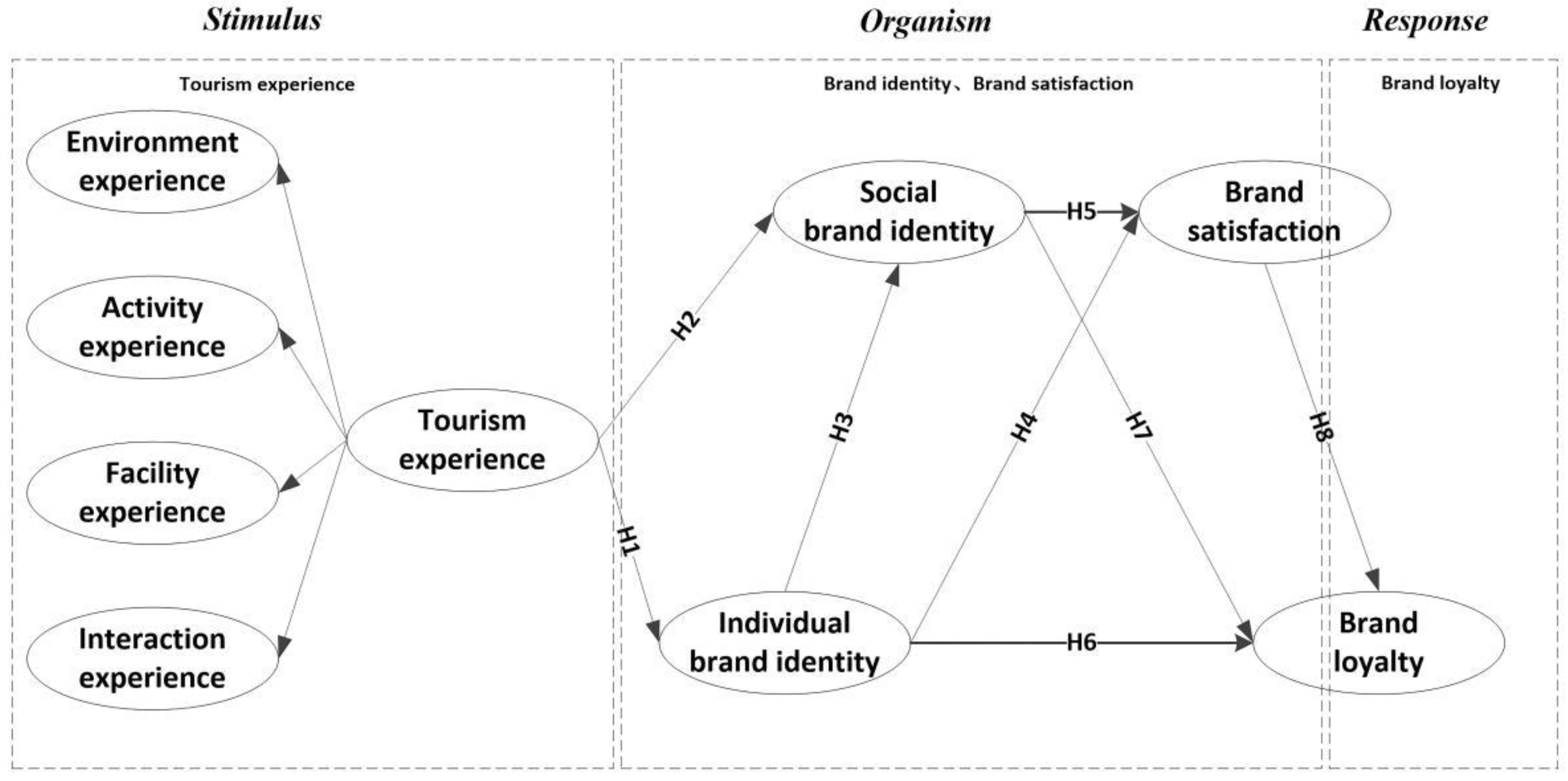

:1. Introduction

- To examine the tourism experience components within the theme park context;

- Explore the relationship between tourists’ experience and their brand identity of theme park;

- Explain the influence path between brand identity and brand loyalty on theme park;

- Explain the influence path between tourists’ tourism experience and their brand loyalty of theme park.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) Theory

2.2. Tourism Experience

2.3. Brand Identity

2.4. Brand Satisfaction and Brand Loyalty

3. Methods

3.1. Study Site and Participants

3.2. Measurement and Instrument Design

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

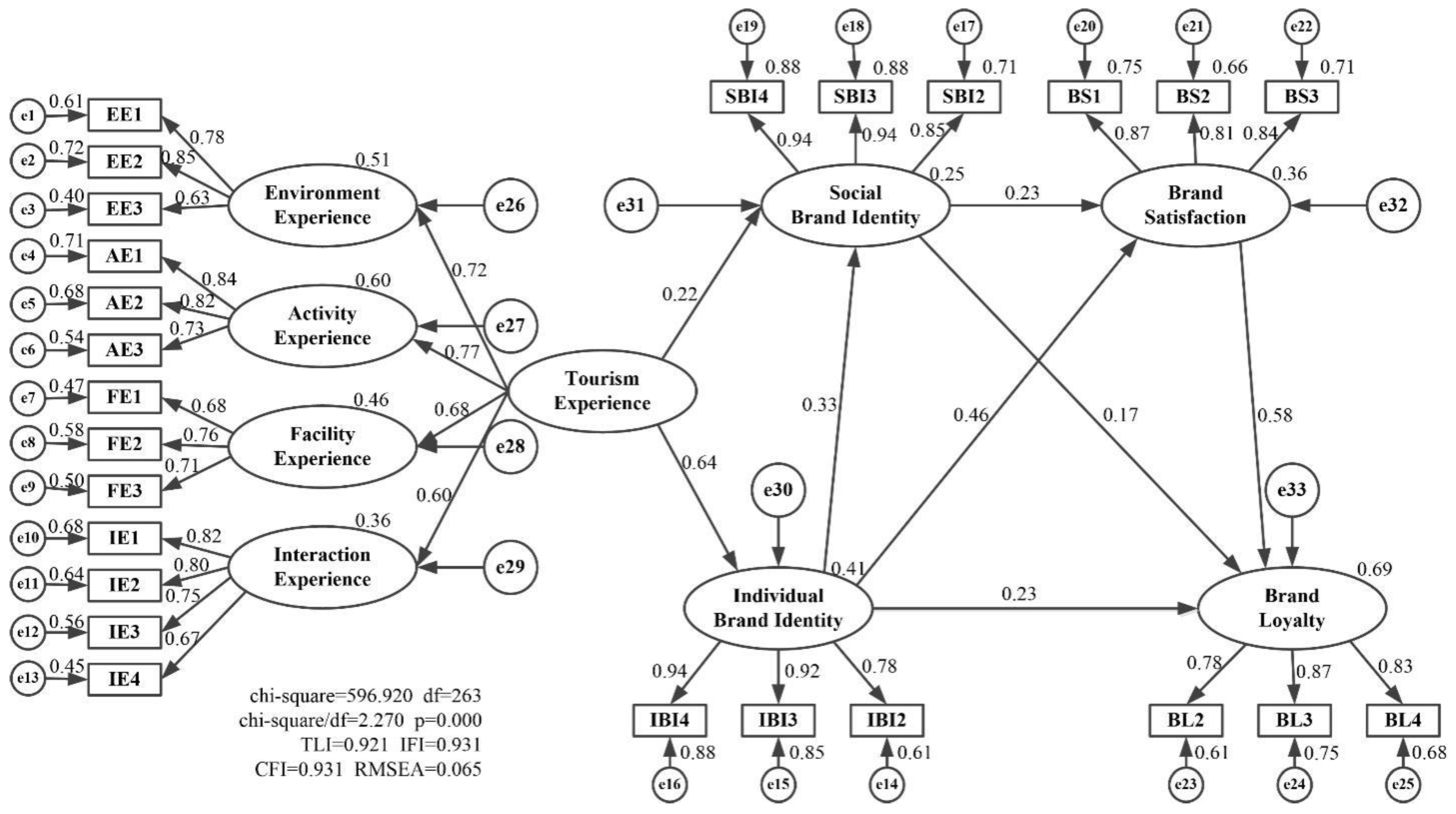

4.2. First-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Second-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.4. Structural Model Evaluation and the Research Hypotheses Testing

4.5. Mediating Effect Test

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, W.; Sung, H.; Suh, E.; Zhao, J. The effects of festival attendees’ experiential values and satisfaction on re-visit intention to the destination: The case of a food and wine festival. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1005–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J. 2019 Tea/Aecom Theme Index and Museum Index. Available online: https://www.teaconnect.org/images/files/TEA_369_18301_201201.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Cheng, Q.; Fang, L.; Chen, H. Visitors’ brand loyalty to a historical and cultural theme park: A case study of hangzhou songcheng, china. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissler, G.L.; Rucks, C.T. The overall theme park experience: A visitor satisfaction tracking study. J. Vacat. Mark. 2011, 17, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the experience economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cabanas, E. Experiencing designs and designing experiences: Emotions and theme parks from a symbolic interactionist perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 16, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Nguyen, T.; Shapoval, V.; Zhai, L. Applying augmented reality (ar) technologies in theatrical performances in theme parks: A transcendent experience perspective. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, A.; Tasci, A.D.; Wei, W. Crowded and popular: The two sides of the coin affecting theme-park experience, satisfaction, and loyalty. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Fong, L.H.N.; Shang, Z.; Gan, M. Rethinking the impact of theme park image on perceived value and behavioral intention: The case of chimelong ocean kingdom, china. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Du, H.; He, F. Research on brand promotion of theme park tourism enterprises based on lovemark theory. Enterp. Econ. 2021, 40, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrba, Ľ.; Kolačkovská, J.; Kršák, B.; Sidor, C.; Lukáč, M. Perception of the impacts of tourism by the administrations of protected areas and sustainable tourism (un) development in slovakia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. The impact of memorable tourism experiences on loyalty behaviors: The mediating effects of destination image and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, M.-D.; Pablos-Heredero, C.D.; Montes-Botella, J.-L. The internal demand of cultural tourism: Understanding satisfaction and fidelity to destination in spain through a non-linear structural model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, Q.Y. Analysis of the evaluation dimensions and causal relationship on theme park visitors’ experience quality: Based on a c-trip comments review of disney and happy valley. Tour. Sci. 2017, 31, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volo, S. Conceptualizing experience: A tourist based approach. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Tourism Experience and Tourism Design. In Design Science in Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bloemer, J.M.; Kasper, H.D. The complex relationship between consumer satisfaction and brand loyalty. J. Econ. Psychol. 1995, 16, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Q.; Cai, R.L. Analysis on the relationship between theme park consumption experience and tourism behavior intention. J. Commer. Econ. 2016, 23, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.Z.; Tang, P. The influencing mechanism of tourism experience quality on visitors’ destination loyalty. J. Anhui Univ. 2022, 46, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, R.; Bond, E.; Baer, R. Building service brands via social identity: Lessons from the sports marketplace. J. Market. Theory Prac. 2001, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokburger-Sauer, N.; Ratneshwar, S.; Sen, S. Drivers of consumer–brand identification. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, Y.; Harris, L. Social identity perspective on brand loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.Y. A brand equity driving model based on brand personality and brand identification. J. Beijing Technol. Bus. Univ. 2006, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A.; Tehseen, S.; Itoo, M.H.; Parrey, S.H. Customer brand identification, affective commitment, customer satisfaction, and brand trust as antecedents of customer behavioral intention of loyalty: An empirical study in the hospitality sector. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. 2019, 29, 196–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.M.; Li, R. Study on the relationship during customer experience, brand identity and brand loyalty: The young customer experience of apple mobile phone as the example. Econ. Manag. 2013, 27, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, L.Q.; Wang, X.Y. Effect tourism destination brand image recognition elements on tourists’ behavior intention: Mediated with brand identification. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2016, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.H.; Xue, Z. Customer perception support, co-creation experience and brand identity. Res. Financ. Econ. Issues 2016, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.L.; Meng, R.; Xu, J.Z. Research on the formation of brand fan effect in new media environment. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2021, 30, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aml, A.; Cjs, B.; Pb, A. Domestic tourists’ experience in protected natural parks: A new trend in pandemic crisis? J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 35, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, W.; Cervera-Taulet, A.; Pérez-Cabañero, C. Exploring the links between destination attributes, quality of service experience and loyalty in emerging mediterranean destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D. Characteristics of the audience for ‘events’ at a heritage site. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1974; pp. 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu, S.A.; Machleit, K.A.; Davis, L.M. Atmospheric qualities of online retailing: A conceptual model and implications. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 54, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J. Stimulus-organism-response reconsidered: An evolutionary step in modeling (consumer) behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, H.L. The influence of hedonic and utilitarian motivations on user engagement: The case of online shopping experiences. Interact. Comput. 2010, 22, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Kim, Y.G. Application of the stimuli-organism-response (sor) framework to online shopping behavior. J. Internet Commer. 2014, 13, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.; Ribeiro, L. The Effect of Atmosphere on Emotions and Online Shopping Intention: Age Differentiation. proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference, Perth, Australia, 28–30 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, F.C.; Agyeiwaah, E.; Lynn, I.; Chen, L. Examining food festival attendees’ existential authenticity and experiential value on affective factors and loyalty: An application of stimulus-organism-response paradigm. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, J.J.; Leong, L.Y.; Tan, G.W.H.; Lee, V.H.; Ooi, K.B. Mobile social tourism shopping: A dual-stage analysis of a multi-mediation model. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, Z.A.; Shalbafian, A.A.; Allam, Z.; Ghaderi, Z.; Murgante, B.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R. Enhancing memorable experiences, tourist satisfaction, and revisit intention through smart tourism technologies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.W. Destination loyalty modeling of the global tourism. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Choe, Y.; Song, H. Brand behavioral intentions of a theme park in China: An application of brand experience. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, Q.G.; Jia, G.Q. Effects of tourist shopping experience elements on customer value, satisfaction, and the purchase intentions. Tour. Trib. 2009, 24, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Jing, J.J. A study of the impacts of religious tourism experiences on the behavioral disposition of tourists: The mediating ef-fect of tourists’ mood. Tour. Sci. 2015, 29, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B.H. Experimental marketing: How to get customers to sense, feel, think, act and relate to your company and brands. Eur. Manag. J. 2000, 18, 695. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Koo, C.; Chung, N. The role of mobility apps in memorable tourism experiences of korean tourists: Stress-coping theory perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Ritchie, J.B.; McCormick, B. Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, A.; Tasci, A.D. Exploring the experiential and sociodemographic drivers of satisfaction and loyalty in the theme park context. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.S.; Si, Y.H.; Li, H. Experience consumption model and implementation plan on the construction of theme parks. Urban Probl. 2008, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. The antecedents of memorable tourism experiences: The development of a scale to measure the destination attributes associated with memorable experiences. Tour. Manag. 2014, 44, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, P.C.; Feng, Y.H. The interaction between brand identity, brand experience and customer loyalty. J. Commer. Econ. 2021, 1, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Jiang, M.H. Content marketing, brand identity and consumer brand loyalty. J. Commer. Econ. 2019, 23, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Wang, J.; Han, H. Effect of image, satisfaction, trust, love, and respect on loyalty formation for name-brand coffee shops. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 79, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Del Bosque, I.R. Csr and customer loyalty: The roles of trust, customer identification with the company and satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.; Sharma, J. Customer engagement for evaluating customer relationships in hotel industry. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Recreat. 2017, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Customer-company identification: A framework for understanding customers relationships with companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Impact of tourists’ perceived value on brand loyalty: A case study of xixi national wetland park. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokha, A.K. Brand equity, brand satisfaction, and brand loyalty: A study of select e-commerce industry. Int. J. Online Mark. 2021, 11, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeho, A.J.; Prentice, R.C. Conceptualizing the experiences of heritage tourists: A case study of new lanark world heritage village. Tour. Manag. 1997, 18, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.-S.; Lee, J.-S.; Lee, C.-K. Measuring festival quality and value affecting visitors’ satisfaction and loyalty using a structural approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, C.-K.; Chung, N.; Kim, W.G. Factors affecting online tourism group buying and the moderating role of loyalty. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Lee, F.; Suh, Y.G. Satisfaction and loyalty from shopping mall experience and brand personality. Serv. Mark. Q. 2015, 36, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Nassen, K.D. Representation of measurement error in marketing variables: Review of approaches and extension to three-facet designs. J. Econom. 1998, 89, 393–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, R.L. Factor Analysis, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, R.; Gore, P.A. A Brief Guide to Structural Equation Modeling. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 719–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (pls) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, R.S.; Edwards, B.D.; Cortina, J.M. On the Practice of Allowing Correlated Residuals among Indicators in Structural Equation Models. In Statistical and Methodological Myths and Urban Legends: Doctrine, Verity and Fable in the Organizational and Social Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hocevar, D. Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First-and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 97, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, R.L. The communicative power of product packaging: Creating brand identity via lived and mediated experience. J. Mark. Theory Prac. 2003, 11, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.Q.; Chen, Y.Y.L.; Liu, X.G. The mechanism of the effect of clothing brand color salience on brand loyalty. J. Silk 2021, 58, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbedweihy, A.M.; Jayawardhena, C.; Elsharnouby, M.H.; Elsharnouby, T.H. Customer relationship building: The role of brand attractiveness and consumer–brand identification. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2901–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.K.; Han, D.; Park, S.B. The effect of brand personality and brand identification on brand loyalty: Applying the theory of social identification. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 2001, 43, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 117 | 38.4 |

| Female | 188 | 61.6 | |

| Age | 18~25 | 91 | 29.8 |

| 26~35 | 133 | 43.6 | |

| 36~45 | 60 | 19.7 | |

| 46 and above | 21 | 6.9 | |

| Occupation | Student | 44 | 14.4 |

| Worker | 10 | 3.3 | |

| Company employee | 127 | 41.6 | |

| Individual laborer | 43 | 14.1 | |

| Enterprise management personnel | 9 | 3.0 | |

| Civil servant | 11 | 3.6 | |

| Education/health/scientific research practitioners | 29 | 9.5 | |

| Retiree | 9 | 3.0 | |

| Other practitioners | 23 | 7.5 | |

| Educational level | Primary/Junior High school | 6 | 2.0 |

| Senior high school/technical school/vocational school | 25 | 8.2 | |

| College | 68 | 22.3 | |

| University | 183 | 60.0 | |

| Graduate school and above | 23 | 7.5 | |

| Income (CNY) | 3000 and under | 43 | 14.1 |

| 3001~6500 | 98 | 32.1 | |

| 6501~10,000 | 121 | 39.7 | |

| 10,001 and above | 43 | 14.1 |

| Construct | Loading | Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment Experience | ||||

| EE1 CTV Nanhai movie theme park has beautiful natural landscape | 0.787 *** | 0.793 | 0.799 | 0.575 |

| EE2 The cultural architecture of CTV Nanhai movie theme park has its own characteristics | 0.856 *** | |||

| EE3 CTV Nanhai movie theme park is clean and tidy | 0.611 *** | |||

| Activity Experience | ||||

| AE1 The activities of CTV Nanhai movie theme park are rich and varied | 0.846 *** | 0.839 | 0.843 | 0.642 |

| AE2 The activities of CTV Nanhai movie theme park are creative | 0.834 *** | |||

| AE3 The activity scene design of CTV Nanhai movie theme park conforms to the theme | 0.717 *** | |||

| Facility Experience | ||||

| FE1 The leisure service facilities of CTV Nanhai movie theme park are perfect | 0.620 *** | 0.755 | 0.766 | 0.529 |

| FE2 The tour guide supporting facilities of CTV Nanhai movie theme park are perfect | 0.892 *** | |||

| FE3 CTV Nanhai movie theme park can provide characteristic tourist souvenirs | 0.639 *** | |||

| Interaction Experience | ||||

| IE1 I get along well with other tourists in CTV Nanhai movie theme park | 0.834 *** | 0.844 | 0.846 | 0.581 |

| IE2 I interact well with other tourists in CTV Nanhai movie theme park | 0.795 *** | |||

| IE3 I think the behavior of other tourists in CTV Nanhai movie theme park is civilized and appropriate | 0.740 *** | |||

| IE4 The activities of CTV Nanhai movie theme park can promote family/couple/parent-child interaction | 0.668 *** | |||

| Individual Brand Identity | ||||

| IBI2 I agree with the values represented by the brand “CTV Media” | 0.780 *** | 0.910 | 0.914 | 0.781 |

| IBI3 I agree with the lifestyle represented by this brand | 0.946 *** | |||

| IBI4 I agree with the tourism services provided by this brand | 0.917 *** | |||

| Social Brand Identity | ||||

| SBI2 Traveling in the theme parks of “CTV Media” can make me gain the respect of others | 0.841 *** | 0.932 | 0.933 | 0.824 |

| SBI3 Traveling in the theme parks of “CTV Media” can help me distinguish myself from different types of people | 0.938 *** | |||

| SBI4 Traveling in the theme parks of “CTV Media” helps me get social recognition | 0.941 *** | |||

| Brand Satisfaction | ||||

| BS1 Generally speaking, I am very satisfied with the theme parks of “CTV Media” | 0.859 *** | 0.878 | 0.881 | 0.711 |

| BS2 Generally speaking, I feel happy to travel to the theme parks of “CTV Media” | 0.802 *** | |||

| BS3 I think it is a good decision to travel to the theme parks of “CTV Media” | 0.867 *** | |||

| Brand Loyalty | ||||

| BL2 Instead of trying other unknown theme parks, I prefer to travel to the theme parks of “CTV Media” | 0.782 *** | 0.864 | 0.865 | 0.682 |

| BL3 I will continue to take “CTV Media” as the preferred tourism destination brand | 0.890 *** | |||

| BL4 I am willing to recommend the theme parks of “CTV Media” to the people around me | 0.802 *** | |||

| BL | BS | SBI | IBI | IE | FE | AE | EE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL | 0.826 | |||||||

| BS | 0.782 | 0.843 | ||||||

| SBI | 0.536 | 0.440 | 0.908 | |||||

| IBI | 0.632 | 0.552 | 0.471 | 0.884 | ||||

| IE | 0.444 | 0.505 | 0.384 | 0.607 | 0.762 | |||

| FE | 0.375 | 0.530 | 0.295 | 0.393 | 0.413 | 0.727 | ||

| AE | 0.349 | 0.488 | 0.291 | 0.404 | 0.370 | 0.579 | 0.801 | |

| EE | 0.341 | 0.494 | 0.262 | 0.426 | 0.326 | 0.447 | 0.665 | 0.758 |

| Model | Chi-Square | df | Chi- Square/df | CFI | GFI | AGFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-order four factor correlation model | 126.654 | 59 | 2.147 | 0.960 | 0.940 | 0.908 | 0.061 |

| Second-order factor model | 132.541 | 61 | 2.173 | 0.957 | 0.940 | 0.910 | 0.062 |

| Recommended value | The smaller the better | The bigger the better | <3.000 | >0.900 | >0.900 | >0.900 | <0.080 |

| Path | Unstd. Path Estimate | S.E. | t-Value | p | Std. Path Estimate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TE | → | IBI | 0.973 | 0.145 | 60.689 | *** | 0.643 |

| IBI | → | SBI | 0.528 | 0.133 | 30.969 | *** | 0.331 |

| TE | → | SBI | 0.524 | 0.226 | 20.317 | 0.021 * | 0.217 |

| IBI | → | BS | 0.429 | 0.061 | 60.975 | *** | 0.460 |

| SBI | → | BS | 0.132 | 0.036 | 30.708 | *** | 0.226 |

| IBI | → | BL | 0.254 | 0.064 | 30.945 | *** | 0.229 |

| SBI | → | BL | 0.121 | 0.035 | 30.438 | *** | 0.174 |

| BS | → | BL | 0.686 | 0.078 | 80.828 | *** | 0.575 |

| Relationship | Point Estimation | Product of Coefficients | Bias-Corrected | Percentile | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | Z | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||

| Direct effect | |||||||

| IBI→BL | 0.254 | 0.078 | 30.256 | 0.109 | 0.415 | 0.104 | 0.411 |

| Indirect effect | |||||||

| ① IBI→SBI→BS→BL | 0.048 | 0.019 | 20.526 | 0.019 | 0.099 | 0.013 | 0.085 |

| ② IBI→SBI→BL | 0.064 | 0.028 | 20.286 | 0.021 | 0.136 | 0.013 | 0.122 |

| ③ IBI→BS→BL | 0.294 | 0.064 | 40.594 | 0.190 | 0.443 | 0.186 | 0.433 |

| Indirect total effect | 0.406 | 0.071 | 50.718 | 0.287 | 0.573 | 0.274 | 0.553 |

| Comparison of chain mediating effects | |||||||

| ② vs. ① | 0.016 | 0.029 | 0.552 | −0.031 | 0.088 | −0.038 | 0.078 |

| ③ vs. ① | 0.246 | 0.066 | 30.727 | 0.131 | 0.393 | 0.131 | 0.394 |

| ③ vs. ② | 0.230 | 0.073 | 30.151 | 0.097 | 0.383 | 0.101 | 0.391 |

| Effect Type | Point Estimation | Product of Coefficients | Bias-Corrected | Percentile | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | Z | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||

| Mediation effect test between tourism experience and brand loyalty: | |||||||

| Total effect | 0.753 | 0.174 | 40.328 | 0.496 | 10.181 | 0.496 | 10.181 |

| Direct effect | 0.000 | 0.000 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Indirect effect | 0.753 | 0.174 | 40.328 | 0.496 | 10.181 | 0.496 | 10.181 |

| Comparison of mediation effect between tourism experience and brand loyalty: | |||||||

| ① TE→ISI→BL | 0.247 | 0.084 | 20.940 | 0.108 | 0.445 | 0.103 | 0.434 |

| ② TE→SBI→BL | 0.064 | 0.043 | 10.488 | 0.010 | 0.193 | 0.005 | 0.172 |

| ③ TE→IBI→SBI→BL | 0.062 | 0.028 | 20.214 | 0.023 | 0.144 | 0.015 | 0.120 |

| ④ TE→SBI→BS→BL | 0.048 | 0.042 | 10.143 | 0.003 | 0.160 | 0.002 | 0.158 |

| ⑤TE→IBI→SBI→BS→BL | 0.047 | 0.019 | 20.474 | 0.021 | 0.098 | 0.014 | 0.086 |

| ⑥ TE→IBI→BS→BL | 0.286 | 0.096 | 20.979 | 0.152 | 0.533 | 0.149 | 0.527 |

| ① vs. ② | 0.184 | 0.088 | 20.091 | 0.025 | 0.375 | 0.019 | 0.368 |

| ① vs. ③ | 0.185 | 0.088 | 20.102 | 0.031 | 0.380 | 0.034 | 0.385 |

| ① vs. ④ | 0.200 | 0.091 | 20.198 | 0.039 | 0.400 | 0.023 | 0.380 |

| ① vs. ⑤ | 0.201 | 0.088 | 20.284 | 0.049 | 0.400 | 0.049 | 0.401 |

| ① vs. ⑥ | −0.039 | 0.120 | −0.325 | −0.330 | 0.151 | −0.315 | 0.157 |

| ② vs. ③ | 0.001 | 0.053 | 0.019 | −0.094 | 0.120 | −0.089 | 0.131 |

| ② vs. ④ | 0.016 | 0.033 | 0.485 | −0.038 | 0.097 | −0.060 | 0.076 |

| ② vs. ⑤ | 0.017 | 0.050 | 0.340 | −0.049 | 0.157 | −0.053 | 0.144 |

| ② vs. ⑥ | −0.223 | 0.098 | −20.276 | −0.459 | −0.072 | −0.454 | −0.068 |

| ③ vs. ④ | 0.015 | 0.060 | 0.250 | −0.105 | 0.115 | −0.129 | 0.102 |

| ③ vs. ⑤ | 0.016 | 0.028 | 0.571 | −0.030 | 0.084 | −0.037 | 0.076 |

| ③ vs. ⑥ | −0.224 | 0.100 | 20.240 | −0.466 | −0.082 | −0.473 | −0.084 |

| ④ vs. ⑤ | 0.001 | 0.045 | 0.022 | −0.052 | 0.107 | −0.048 | 0.123 |

| ④ vs. ⑥ | −0.239 | 0.094 | −20.543 | −0.485 | −0.099 | −0.454 | −0.086 |

| ⑤ vs. ⑥ | −0.240 | 0.096 | −20.500 | −0.475 | −0.105 | −0.478 | −0.106 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, L.; Ouyang, F.; Li, Y.; Zhan, J.; Akhtar, N.; Ittefaq, M. Examining the Factors Influencing Tourists’ Destination: A Case of Nanhai Movie Theme Park in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11419. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811419

Zhou L, Ouyang F, Li Y, Zhan J, Akhtar N, Ittefaq M. Examining the Factors Influencing Tourists’ Destination: A Case of Nanhai Movie Theme Park in China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11419. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811419

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Liting, Fei Ouyang, Yang Li, Jieling Zhan, Nadeem Akhtar, and Muhammad Ittefaq. 2022. "Examining the Factors Influencing Tourists’ Destination: A Case of Nanhai Movie Theme Park in China" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11419. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811419

APA StyleZhou, L., Ouyang, F., Li, Y., Zhan, J., Akhtar, N., & Ittefaq, M. (2022). Examining the Factors Influencing Tourists’ Destination: A Case of Nanhai Movie Theme Park in China. Sustainability, 14(18), 11419. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811419