Investigating the Effects of Video-Based E-Word-of-Mouth on Consumers’ Purchase Intention: The Moderating Role of Involvement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

2.1. Video-Based Electronic Word-of-Mouth and Purchase Intention

2.2. Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM)

2.3. Consumers Involvement

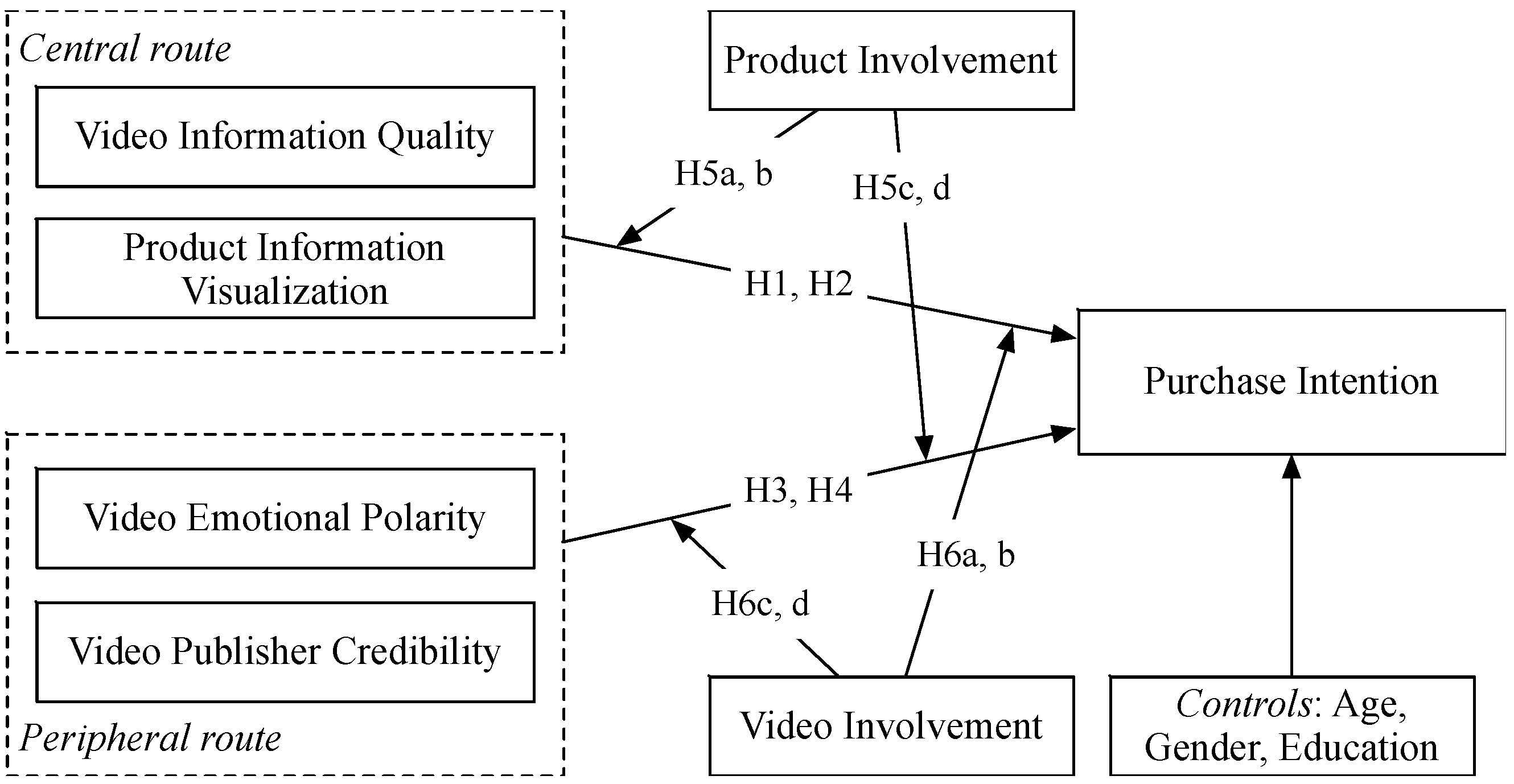

3. Research Model and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Relationships between Central Route Factors and Purchase Intention

3.2. Relationships between Peripheral Route Factors and Purchase Intention

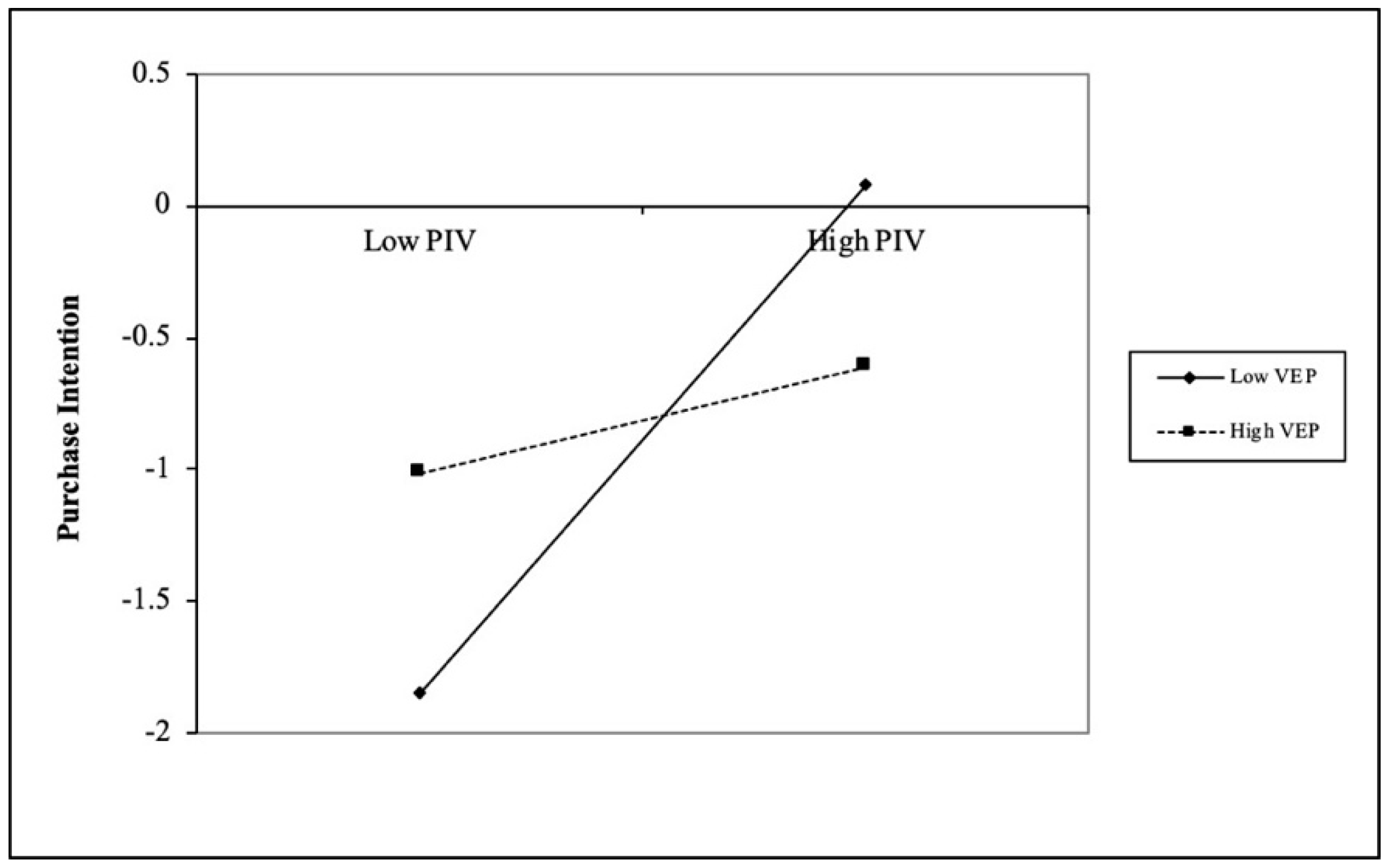

3.3. Moderating Role of Product Involvement

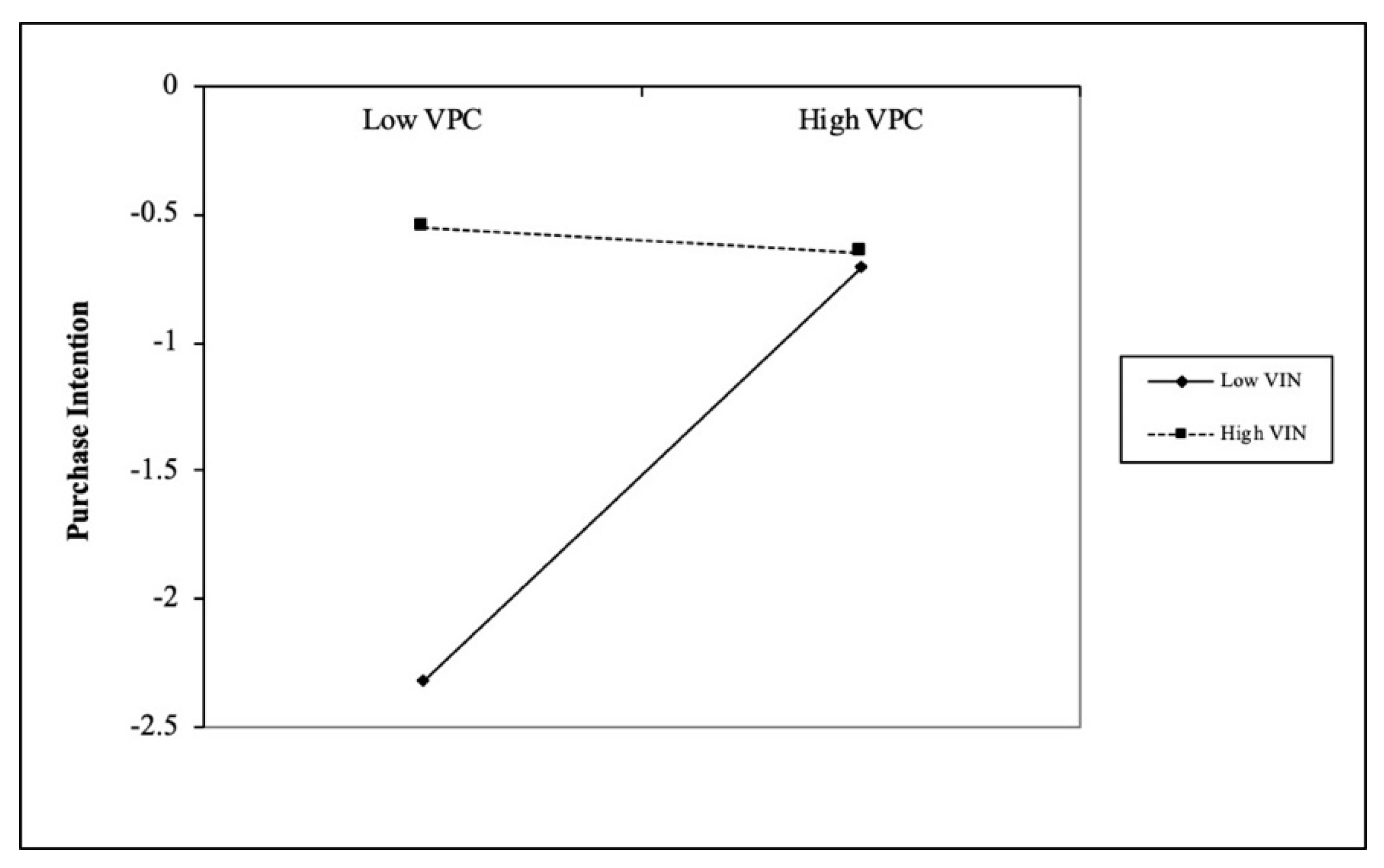

3.4. Moderating Role of Video Involvement

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Measurement Development

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Common Method Bias (CMB)

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Measurement Model

5.2. Structural Model

5.3. Qualitative Results

6. Discussion, Implications, and Future Research

6.1. Key Findings

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frade, J.L.H.; de Oliveira, J.H.C.; Giraldi, J.d.M.E. Advertising in streaming video: An integrative literature review and research agenda. Telecommun. Policy 2021, 45, 102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Yang, J.; Zhu, M.; Majeed, S. Relationship between consumer participation behaviors and consumer stickiness on mobile short video social platform under the development of ICT: Based on value co-creation theory perspective. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2021, 27, 697–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.R.; Mittal, D. Optimizing customer engagement content strategy in retail and E-tail: Available on online product review videos. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.N.; Fischer, E.; Yongjian, C. How Does Brand-related User-generated Content Differ across YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter? J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellis, G.J.; MacInnis, D.J.; Tirunillai, S.; Zhang, Y. What drives virality (sharing) of online digital content? The critical role of information, emotion, and brand prominence. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Vedula, N.; Sun, W.; Lee, H.; Gupta, H.; Ogihara, M.; Johnson, J.; Ren, G.; Parthasarathy, S. Multimodal content analysis for effective advertisements on YouTube. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–21 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tafesse, W. YouTube marketing: How marketers’ video optimization practices influence video views. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 1689–1707. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.-I.; Cheng, S.-Y.; Shih, Y.-T. Effects among product attributes, involvement, word-of-mouth, and purchase intention in online shopping. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2017, 22, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, A.; Kumar, S.R. Electronic word-of-mouth and the brand image: Exploring the moderating role of involvement through a consumer expectations lens. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballon, P.; Van Hoed, M.; Schuurman, D. The effectiveness of involving users in digital innovation: Measuring the impact of living labs. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1202–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, Z.; Farah, M.; Kassab, D. Amazon’s approach to consumers’ usage of the Dash button and its effect on purchase decision involvement in the U. S. market. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.Y.Y.; Ngai, E.W.T. Conceptualising electronic word of mouth activity: An input-process-output perspective. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2011, 29, 488–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Ha, L. Which form of word-of-mouth is more important to online shoppers? a comparative study of WOM use between general population and college students. J. Commun. Media Res. 2015, 7, 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Moisescu, O.; Dan, I.; Gică, O. An examination of personality traits as predictors of electronic word-of-mouth diffusion in social networking sites. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 21, 450–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobon, S.; García-Madariaga, J. The Influence of Opinion Leaders’ eWOM on Online Consumer Decisions: A Study on Social Influence. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, N.C.; Zhang, R.; Ha, L. Does valence of product review matter? The mediating role of self-effect and third-person effect in sharing YouTube word-of-mouth (vWOM). J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2019, 13, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, B.M.; Reith, R. Cultural differences in the perception of credible online reviews—The influence of presentation format. Decis. Support Syst. 2022, 154, 113710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.M.; Lu, K.; Wu, J. The effects of visual information in eWOM communication. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2012, 6, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, S.; Khong, K.W.; Goh, W.W.; Chong, A.Y.L. Examining the antecedents of persuasive eWOM messages in social media. Online Inf. Rev. 2014, 38, 746–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.-C.; Chuang, H.H.-C.; Liang, T.-P. Elaboration likelihood model, endogenous quality indicators, and online review helpfulness. Decis. Support Syst. 2021, 153, 113683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Koh, N.S.; Reddy, S.K. Ratings lead you to the product, reviews help you clinch it? The mediating role of online review sentiments on product sales. Decis. Support Syst. 2014, 57, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, H.; Yang, Y.; Pan, X.; Zhang, Z.; An, W. Sentiment analysis for online reviews using conditional random fields and support vector machines. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 20, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopezosa, C.; Orduna-Malea, E.; Perez-Montoro, M. Making video news visible: Identifying the optimization strategies of the cybermedia on YouTube using webmetrics. Journal. Pract. 2019, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Bose, I.; Koh, N.S.; Liu, L. Manipulation of online reviews: An analysis of ratings, readability, and sentiments. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 52, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Aakash, A.; Aggarwal, A.G.; Kapur, P.K. Analyzing the impact of review recency on helpfulness through econometric modeling. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2021, 12, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.; Thadani, D.R. The impact of electronic word-of-mouth communication: A literature analysis and integrative model. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 54, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, H.; He, W.; Hong, C. What influences online reviews’ perceived information quality? Electron. Libr. 2020, 38, 273–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and Validation of a Scale to Measure Celebrity Endorsers’ Perceived Expertise, Trustworthiness, and Attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baber, A.; Thurasamy, R.; Malik, M.I.; Sadiq, B.; Islam, S.; Sajjad, M. Online word-of-mouth antecedents, attitude and intention-to-purchase electronic products in Pakistan. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See-To, E.W.; Ho, K.K. Value co-creation and purchase intention in social network sites: The role of electronic Word-of-Mouth and trust—A theoretical analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-H.; Hsu, I.-C.; Lin, C.-C. Website attributes that increase consumer purchase intention: A conjoint analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Bechwati, N.N. Word of mouse: The role of cognitive personalization in online consumer reviews. J. Interact. Advert. 2008, 9, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkan, I.; Evans, C. The influence of eWOM in social media on consumers’ purchase intentions: An extended approach to information adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Costa, C.; Oliveira, T.; Gonçalves, R.; Branco, F. How smartphone advertising influences consumers’ purchase intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Hyun, H.; Thavisay, T. A study of antecedents and outcomes of social media WOM towards luxury brand purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The effects of involvement on responses to argument quantity and quality: Central and peripheral routes to persuasion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghakhani, N.; Oh, O.; Gregg, D.G.; Karimi, J. Online Review Consistency Matters: An Elaboration Likelihood Model Perspective. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 23, 1287–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, M.H.; Ghazali, E.; Mohtar, M. The role of elaboration likelihood model in consumer behaviour research and its extension to new technologies: A review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 664–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-H.; Lee, J.; Han, I. The Effect of On-Line Consumer Reviews on Consumer Purchasing Intention: The Moderating Role of Involvement. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2007, 11, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.A.; Krampf, R.F.; Palmer, J.W. The role of interface in electronic commerce: Consumer involvement with print versus online catalogs. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2001, 5, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celsi, R.L.; Olson, J.C. The role of involvement in attention and comprehension processes. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Moutinho, L. The role of brand image, product involvement, and knowledge in explaining consumer purchase behaviour of counterfeits: Direct and indirect effects. Eur. J. Mark. 2011, 45, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, S.; Khong, K.W.; Chong, A.; Lin, B. Examining the Impacts of Electronic Word-of-Mouth Message on Consumers’ Attitude. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2017, 57, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.-H.; Hu, D.-C.; Chung, Y.-C.; Huang, A.-P. Risk and opportunity for online purchase intention—A moderated mediation model investigation. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 62, 101621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Chang, Y.-C. What drives purchase intention on Airbnb? Perspectives of consumer reviews, information quality, and media richness. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1512–1523. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Tang, H.; Zhang, Y. Electronic word-of-mouth and consumer purchase intentions in social e-commerce. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2020, 41, 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwanji, V.S.; Cortese, J. Contrasting user generated videos versus brand generated videos in ecommerce. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljukhadar, M.; Senecal, S. Communicating online information via streaming video: The role of user goal. Online Inf. Rev. 2017, 41, 378–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Chen, L.; Santhanam, R. Will video be the next generation of e-commerce product reviews? Presentation format and the role of product type. Decis. Support Syst. 2015, 73, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.-I.; Stoel, L. Using rich media to motivate fair-trade purchase. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2017, 11, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Du, R. The Effects of Review Presentation Formats on Consumers’ Purchase Intention. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, C. Social interaction-based consumer decision-making model in social commerce: The role of word of mouth and observational learning. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, D.-H.; Han, I. The effect of negative online consumer reviews on product attitude: An information processing view. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2008, 7, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Yin, G.; He, W. Is this opinion leader’s review useful? Peripheral cues for online review helpfulness. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2014, 15, 267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, H.S.; Voyer, P.A. Word-of-Mouth Processes Within a Services Purchase Decision Context. J. Serv. Res. 2000, 3, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strubel, J.; Petrie, T.A. The clothes make the man: The relation of sociocultural factors and sexual orientation to appearance and product involvement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Issue involvement as a moderator of the effects on attitude of advertising content and context. Adv. Consum. Res. 1981, 8, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Kim, K.J.; Sundar, S.S. Customization in location-based advertising: Effects of tailoring source, locational congruity, and product involvement on ad attitudes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 51, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Bai, X. An empirical study on continuance intention of mobile social networking services. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2014, 26, 168–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D. Managing User Trust in B2C e-Services. E-Serv. J. 2003, 2, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta-Bergman, M.J. The Impact of Completeness and Web Use Motivation on the Credibility of e-Health Information. J. Commun. 2004, 54, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. The Personal Involvement Inventory: Reduction, Revision, and Application to Advertising. J. Advert. 1994, 23, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The Behavioral Consequences of Service Quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vijver, F.J.R.; Leung, K. Methods and data analysis of comparative research. In Handbook of Cross-Culturalpsychology: Theory and Method; Berry, J.W., Poortinga, Y.H., Pandey, J., Eds.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, B.; Rayport, J. TikTok: Super App or Supernova? 2021. Available online: https://hbr.org/podcast/2021/11/tiktok-super-app-or-supernova (accessed on 31 July 2022).

- Beauchemin, C.; González-Ferrer, A. Sampling international migrants with origin-based snowballing method: New evidence on biases and limitations. Demogr. Res. 2011, 25, 103–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Armstrong, J.; Overton, T. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, L.J.; Hartman, N.; Cavazotte, F. Method variance and marker variables: A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 477–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mason, C.H.; Perreault, W.D., Jr. Collinearity, power, and interpretation of multiple regression analysis. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Fang, Y.; Lim, K.H. Understanding sustained participation in transactional virtual communities. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 53, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhue, D.; Lewis, W.; Thompson, R. Statistical power in analyzing interaction effects: Questioning the advantage of PLS with product indicators. Inf. Syst. Res. 2007, 18, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regress: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ismagilova, E.; Slade, E.L.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. The Effect of Electronic Word of Mouth Communications on Intention to Buy: A Meta-Analysis. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 22, 1203–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.; Lennon, S.J. E-atmosphere, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2010, 14, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Definition |

|---|---|

| Video information quality | The extent to which the video information is perception of precision, credibility, relevance, comprehensibility, and timeliness [26]. |

| Product information visualization | The extent to which consumers are able to comprehensively comprehend the product information expressed in the review videos [25]. |

| Video emotion polarity | The extent to which consumers are attracted or affected by the emotion polarity (positive emotion) toward the product in the video [27]. |

| Video publisher credibility | The extent to which consumers perception of the video publisher is credible [28]. |

| Category | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 110 (65.1) |

| Female | 59 (34.9) | |

| Education | High school or below | 12 (7.1) |

| College | 12 (7.1) | |

| University or above | 145 (85.8) | |

| Age | Under 20 | 9 (5.3) |

| 21–25 | 107 (63.3) | |

| 36–40 | 2 (1.2) | |

| 41 and above | 51 (30.2) | |

| Construct | Indicator | Substantive Factor Loading (R1) | R12 | Method Factor Loading(R2) | R22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Video Information Quality (VIQ) | VIQ1 | 0.883 *** | 0.780 | −0.079 | 0.006 |

| VIQ2 | 0.935 *** | 0.874 | −0.060 | 0.004 | |

| VIQ3 | 0.738 *** | 0.545 | 0.025 | 0.001 | |

| VIQ4 | 0.690 *** | 0.476 | 0.125 | 0.016 | |

| Video Emotional Polarity (VEP) | VEP1 | 0.927 *** | 0.859 | −0.008 | 0.000 |

| VEP2 | 0.918 *** | 0.843 | 0.008 | 0.000 | |

| Video Information Visualization (VIV) | VIV1 | 0.821 *** | 0.674 | −0.022 | 0.000 |

| VIV2 | 0.746 *** | 0.557 | 0.041 | 0.002 | |

| VIV3 | 0.897 *** | 0.805 | −0.016 | 0.000 | |

| VIV4 | 0.821 *** | 0.674 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Video Publisher Credibility (VPC) | VPC1 | 0.842 *** | 0.709 | 0.041 | 0.002 |

| VPC2 | 0.902 *** | 0.814 | 0.013 | 0.000 | |

| VPC3 | 0.877 *** | 0.769 | 0.021 | 0.000 | |

| VPC4 | 0.988 *** | 0.976 | −0.072 | 0.005 | |

| Video Involvement (VIN) | VIN1 | 0.837 *** | 0.701 | 0.017 | 0.000 |

| VIN2 | 0.917 *** | 0.841 | −0.065 | 0.004 | |

| VIN3 | 0.863 *** | 0.745 | 0.063 | 0.004 | |

| VIN4 | 0.892 *** | 0.796 | −0.017 | 0.000 | |

| Product Involvement (PIN) | PIN1 | 0.945 *** | 0.893 | −0.035 | 0.001 |

| PIN2 | 0.946 *** | 0.895 | 0.004 | 0.000 | |

| PIN3 | 0.874 *** | 0.764 | 0.032 | 0.001 | |

| Purchase Intention (PUI) | PUI1 | 0.841 *** | 0.707 | 0.116 ** | 0.013 |

| PUI2 | 0.981 *** | 0.962 | −0.050 | 0.003 | |

| PUI3 | 0.999 *** | 0.998 | −0.065 | 0.004 | |

| Average | 0.878 | 0.777 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| Construct | Indicator | Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Video Information Quality (VIQ) | VIQ1 | 0.814 | 0.830 | 0.887 | 0.662 |

| VIQ2 | 0.868 | ||||

| VIQ3 | 0.744 | ||||

| VIQ4 | 0.825 | ||||

| Video Emotional Polarity (VEP) | VEP1 | 0.916 | 0.825 | 0.919 | 0.851 |

| VEP2 | 0.929 | ||||

| Product Information Visualization (PIV) | PIV1 | 0.791 | 0.840 | 0.893 | 0.677 |

| PIV2 | 0.763 | ||||

| PIV3 | 0.894 | ||||

| PIV4 | 0.837 | ||||

| Video Publisher Credibility (VPC) | VPC1 | 0.865 | 0.924 | 0.946 | 0.815 |

| VPC2 | 0.915 | ||||

| VPC3 | 0.904 | ||||

| VPC4 | 0.925 | ||||

| Video Involvement (VIN) | VIN1 | 0.829 | 0.900 | 0.930 | 0.769 |

| VIN2 | 0.867 | ||||

| VIN3 | 0.917 | ||||

| VIN4 | 0.892 | ||||

| Product Involvement (PIN) | PIN1 | 0.917 | 0.911 | 0.944 | 0.850 |

| PIN2 | 0.946 | ||||

| PIN3 | 0.902 | ||||

| Purchase Intention (PUI) | PUI1 | 0.937 | 0.935 | 0.958 | 0.885 |

| PUI2 | 0.939 | ||||

| PUI3 | 0.947 |

| Mean | S.D. | VIQ | VEP | PIV | VPC | VIN | PIN | PUI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIQ | 4.997 | 1.062 | 0.814 | ||||||

| VEP | 4.787 | 1.320 | 0.320 (0.394) | 0.922 | |||||

| PIV | 4.644 | 0.981 | 0.623 (0.757) | 0.310 (0.377) | 0.823 | ||||

| VPC | 5.260 | 1.082 | 0.686 (0.782) | 0.469 (0.539) | 0.636 (0.718) | 0.903 | |||

| VIN | 4.231 | 1.251 | 0.401 (0.461) | 0.410 (0.484) | 0.384 (0.444) | 0.378 (0.409) | 0.877 | ||

| PIN | 4.357 | 1.049 | 0.522 (0.605) | 0.248 (0.284) | 0.465 (0.532) | 0.396 (0.432) | 0.635 (0.708) | 0.922 | |

| PUI | 4.836 | 1.303 | 0.537 (0.599) | 0.315 (0.357) | 0.617 (0.692) | 0.677 (0.721) | 0.492 (0.529) | 0.443 (0.479) | 0.941 |

| Construct | DV = Purchase Intention | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Gender | 0.216 ** | 0.291 *** | 0.272 *** |

| Age | 0.027 | 0.013 | 0.002 |

| Education | 0.144 | −0.031 | −0.021 |

| VIQ (H1) | 0.077 | 0.137 | |

| PIV (H2) | 0.382 *** | 0.449 *** | |

| VEP (H3) | 0.057 | 0.030 | |

| VPC (H4) | 0.327 *** | 0.212 * | |

| VEP × VIQ | 0.358 *** | ||

| VEP × PIV | −0.359 *** | ||

| VPC × VIQ | −0.227 | ||

| VPC × PIV | 0.175 | ||

| R2 | 0.079 | 0.579 | 0.630 |

| △R2 | 0.499 | 0.051 | |

| F (p-value) | 0.079 ** | 47.703 *** | 5.388 *** |

| Construct | DV = Purchase Intention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Gender | 0.216 ** | 0.291 *** | 0.274 *** | 0.231 *** |

| Age | 0.027 | 0.013 | −0.019 | 0.009 |

| Education | 0.144 | −0.031 | 0.026 | 0.050 |

| VIQ | 0.077 | 0.031 | 0.034 | |

| PIV | 0.382 *** | 0.302 *** | 0.252 *** | |

| VEP | 0.057 | −0.031 | −0.022 | |

| VPC | 0.327 *** | 0.334 *** | 0.290 *** | |

| PIN | 0.010 | 0.077 | ||

| VIN | 0.280 *** | 0.351 *** | ||

| PIN × VIQ (H5a) | −0.310 ** | |||

| PIN × PIV (H5b) | 0.038 | |||

| PIN × VEP (H5c) | −0.141 * | |||

| PIN × VPC (H5d) | 0.159 | |||

| VIN × VIQ (H6a) | 0.203 * | |||

| VIN × PIV (H6b) | 0.045 | |||

| VIN × VEP (H6c) | 0.112 | |||

| VIN × VPC (H6d) | −0.376 ** | |||

| R2 | 0.079 | 0.579 | 0.633 | 0.725 |

| △R2 | 0.499 | 0.054 | 0.092 | |

| F (p-value) | 4.742 ** | 47.702 *** | 11.812 *** | 6.306 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhai, L.; Yin, P.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, M. Investigating the Effects of Video-Based E-Word-of-Mouth on Consumers’ Purchase Intention: The Moderating Role of Involvement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9522. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159522

Zhai L, Yin P, Li C, Wang J, Yang M. Investigating the Effects of Video-Based E-Word-of-Mouth on Consumers’ Purchase Intention: The Moderating Role of Involvement. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9522. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159522

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhai, Lingyun, Pengzhen Yin, Chenyang Li, Jingjing Wang, and Min Yang. 2022. "Investigating the Effects of Video-Based E-Word-of-Mouth on Consumers’ Purchase Intention: The Moderating Role of Involvement" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9522. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159522

APA StyleZhai, L., Yin, P., Li, C., Wang, J., & Yang, M. (2022). Investigating the Effects of Video-Based E-Word-of-Mouth on Consumers’ Purchase Intention: The Moderating Role of Involvement. Sustainability, 14(15), 9522. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159522