Abstract

Intangible cultural heritage tourism has become a hot topic in academia and industry. As a vital tourism resource, intangible cultural heritage can activate the in-depth experience of tourists for local culture to enhance the attraction and competitive advantage of national or regional tourism. From the perspective of culture, design is used to realize a kind of life taste and form a lifestyle through cultural creativity and industry, with applications in different fields to create a human lifestyle through innovative design. This study proposed a framework exploring form and ritual and discusses the aesthetic economy from form (Hi-tech) to ritual (Hi-touch) through case studies. There were three cases that analyzed how to improve local tourism development through the interaction between form and ritual. The results show that this model can integrate sustainable development into intangible cultural heritage tourism and can be further verified in other countries and regions.

1. Introduction

Since the 1990s, the study of livelihood in rural areas has become an essential issue in alleviating rural poverty [1]. The sustainable development of indigenous livelihoods requires affirmation and protection of the wisdom of local cultures [2]. Intangible cultural heritage is the essence of local folk culture and an important part of cultural heritage. In 2003, the UNESCO General Conference adopted the “Convention for the Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage”, which aims to protect the intangible cultural heritage of various countries, including the research, preservation, protection, publicity, promotion, inheritance, and revitalization of heritage in all aspects. The relevance of intangible cultural heritage and sustainable development has been widely recognized and advocated by major international organizations (e.g., ICOMOS 2011; UNESCO 2013, 2015; UN-HABITAT 2016) [3]. Travel has already become an inseparable part of human lives, even in times of global world problems. However, serious problems such as excessive energy consumption and increasingly severe negative environmental impacts, including climate change, need to be solved urgently [4]. Many scholars are exploring how to realize tourism’s cultural and social values except for economic benefits. Research on intangible cultural heritage tourism has become an academic hotspot, especially the impact of intangible cultural heritage tourism. As a valuable tourism resource, intangible cultural heritage provides the possibility for the development of the corresponding tourism industry. Under the upsurge of public concern, intangible cultural heritage, as an important tourism resource to enhance the attraction and competitiveness of national or regional tourism, is increasingly recognized. The potential demand of tourists for an intangible cultural heritage tourism experience is enormous, and a large number of tourist groups may become consumers of intangible cultural heritage tourism [5]. Culture and its heritage reflect and shape values, beliefs, and aspirations, thereby defining a people’s national identity. It is crucial to preserve our cultural heritage because it keeps our integrity as a people. In addition to its intrinsic value, culture provides important social and economic benefits. With improved learning and health, increased tolerance, and opportunities to come together with others, culture enhances our quality of life and increases overall well-being for both individuals and communities. In addition, culture is a driver of sustainable development. Therefore, culture must be integrated into sustainable development strategies.

According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, in 2019, the number of domestic tourists in China reached 6.006 billion, the number of outbound tourists was nearly 150 million, and the number of inbound tourists exceeded 60 million, making China the world’s largest tourism country and the country with the highest number of domestic and foreign tourists. However, because of COVID-19, the number of domestic tourists in China was 2.879 billion in 2020 and 3.246 billion in 2021, with a total decrease of 52.1% and 46%, respectively, compared with 2019 (NBSPRC, 2022). Reactivating the development of tourism through cultural innovation has become an urgent research topic. The value of cultural innovation has changed from the pursuit of Hi-tech quality of form in the past to the Hi-touch taste of ritual, forming an aesthetic economy from Hi-tech to Hi-touch to add value to tourism in ethnic minority areas and help local people eliminate poverty and become rich.

Minority areas retain a large number of intangible cultural resources, which is the cultural wealth accumulated by locals over a long period of time. However, today, with society’s rapid development, they are facing the dilemma of losing vitality. How to better inherit and continue these unique cultures and achieve sustainable development is an important research topic. The custom of eating together has always been one of the enduring research topics in anthropology and ethnology [6], through a study of communal meals at religious and sacrificial ceremonies, and states that “those who eat and drink together are closely linked by a bond of friendship and mutual responsibility”. The form of eating together has the cultural function of constructing “we belong to the same community” among people. In Chinese culture, as a symbol of social status, etiquette status, special occasions, and other social affairs, food is not only a nutritional resource but also a means of communication. The “Zhuanzhuanjiu” (Turning wine) of the Dong and Yi ethnic groups, the “Tongxinjiu” (Concentric wine) of the Lisu and Dulong ethnic groups, and the “Lianbei” (Continuous cup) of drinking of the Paiwan ethnic groups in Taiwan all use the method of drinking together to share delicious wine. Being a beverage made by brewing, wine is actually a cultural extension of human food and has two layers of “cultural” and “super-cultural” properties. With the concept of sustainable development of intangible cultural heritage tourism, foreign tourists can enhance their in-depth experience of local culture in the ceremonies of different activities, strengthen the communication effect of culture, and at the same time enable local people to better recognize the value of local culture. This ensures that cultural memory can be passed on from generation to generation and makes rational use of traditional culture to form a benign interaction and achieve sustainable development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Development of Cultural Heritage Tourism

Cultural heritage is an important factor for the sustainable development of tourism, which can improve public awareness and support for cultural relics protection, and also make a great contribution to poverty alleviation and the protection of nature and culture [7]. Jokela et al. [8] discussed how art and design practices might help support and develop renewable economies in the Arctic. The dimensions of sustainability in this context include cultural and social sustainability, which means that contemporary renewable productions must respect cultural diversity and heritage and be produced in collaboration with local inhabitants to share economic benefits with the region. Practical ideas and potential strategies for developing the use of arts-based methods in creative tourism were presented by Huhmarniemi et al. [9].

Developing countries are rich in intangible cultural heritage, and the development of tourism by villagers can reinforce the importance of their traditional culture, bring them a sense of pride and identity, and create (rebuild) their new identities through tourism [10,11]. It also enhances the sense of experience and promote sustainable development. Through festival tourism products, ethnic villages create an in-depth experience to improve cultural taste, excavate ethnic culture, cultivate festival brands, carry out experiential tourism, develop unique tourism products, enhance the participation of tourism projects, and create an authenticity theme experience. Sacred values reflect the authentic character of local culture [12]. Sincere encounters enable tourists to participate in genuine cultural exchanges or interactive experiences [13].

Cultural commercialization can be regarded as a means for people to reevaluate their history [10]. The combination of tourism poverty alleviation and intangible cultural heritage tourism in ethnic areas can improve the quality of life of poor people and establish cultural and ecological protection areas. Community participation in intangible cultural heritage tourism development is conducive to protecting and cultivating the living space of intangible cultural heritage, inspiring and highlighting the cultural consciousness of the inheritance subject, and exploring and displaying the spiritual connotation of intangible cultural heritage. Tourist artworks that absorb ancient culture are not only a response to consumer demand, but also a response to nationalism.

The authenticity of intangible heritage is rooted in the location of the heritage, and they expect a local performance. At the same time, there is still a primitive spiritual connection between off-domain existential intangible heritage tourism and the heritage identity. Studies have shown that when events take place far away from the source of cultural traditions, tourists can also obtain a high degree of authenticity perception, and there are significant group differences [14]. Chronis [15] believes that tourists are not passive text readers during story performances but actively participate in negotiation and fill in gaps and imagination by using their previous background knowledge. In the interactive performance, with the jointly constructed text circles in the live culture, read by its members and further changed through constant reinterpretation and changing social context, a co-construction culture model is constructed, illustrating that the living inheritance of intangible cultural heritage in the tourism field is precious.

2.2. Cultural Innovation Design

Creative cultural design has two purposes: to preserve people’s memory of history and skill of life; that is, intangible cultural assets and tangible cultural assets. As far as historical memory is concerned, it must pass through real hardware (building or field) to store people’s memories. From the perspective of creative design, people should not only keep the tangible field, but the main purpose should be making this field a perceptual field (situation), in order to evoke people’s historical memory. This, according to this memory, then provides people with a touching experience to stimulate people’s life, and then connects the surrounding fields to build a sensory life circle, so as to encourage people to create a creative life with cultural connotation. The regional knowledge system is formed in situated learning in relation to local ecocultures, traditions, and diverse indigenous and non-indigenous cultures. The knowledge can be adopted by newcomers and even guests when participating in ecocultures [16]. Therefore, the purpose of cultural innovation design is to “create a perceptual field (form), provide a moving experience (ritual) and construct a sensory life (situation)” through creativity. As far as life skills are concerned, the purpose is to stimulate creativity with intangible assets, and then reproduce the creativity from cultural meaning in modern life using modern technology. Intangible cultural assets can only show their skills through tangible daily necessities.

In the face of the rapid development of information technology, designers should act as “interpreters of technology, leaders of human nature, creators of sensibility and makers of taste”. Among them, the makers of taste are Hi-touch which moves consumption. Hi-touch cultural and creative products express human nature, while Hi-tech industrial products pursue material nature. Cultural and creative products are Hi-touch and appeal to sensibility; industrial products are Hi-tech and appeal to rationality. Cultural and creative products focus on the story of life, while industrial products pursue the rationality of production. Therefore, cultural and creative products usually have a moving story, which can enrich the connotation of life. Through cultural creativity, they can express the quality of Hi-tech and appeal to the taste of Hi-touch. From the perspective of cultural creativity, the aesthetic economy is the best interpretation from Hi-tech to Hi-touch [17]. Cultural innovation design should protect people’s most meaningful life memory and most exquisite life skills, and consider how to integrate with the cultural and creative industry to form the cultural relics preservation of upstream memory and skills and stimulate designers’ creative design. It is also to let the creativity originate from cultural relics, form the creativity with cultural connotation into products, and then use innovative products for life, and finally let enterprises become brands, so as to achieve the so-called purpose of “originating from cultural relics, forming in products, being used for life, and becoming a brand”. From the perspective of the cultural and creative industry, “thinking of the ancients and originating from cultural relics” is the purpose of cultural relics’ preservation to achieve the cultural and creative industry of “making good use of science and technology and reproducing elegance” [18,19]. After preserving cultural relics, how to play the follow-up “creating a perceptual field, providing a moving experience, and constructing a sensory life” should comprehensively consider the form and ritual of cultural innovation design.

2.3. Memory and Innovative Design

Memory is a narrative of the past and time, and memory can travel back and forth between the past and reality with the help of imagination [20]. Memory is attached to specific things such as space, pictures, and objects [21]. Events and objects cannot be remembered by themselves, but as special ideograms; they can create an atmosphere of memory and act as a catalyst to stimulate memory. Cultural memory is the collective memory of a nation or country. In communication, cultural memory relies on organized and public collective communication. Ritual coherence (rituelle Kohärenz) is an important way of inheritance [22]. Ritual has two meanings: one is rituals and customs in the sense of religion; the other is the etiquette, customs, and procedures in life. As a medium and form of cultural memory, ritual refers to particular celebration ceremonies at special times and occasions [23].

As a group, our identity will be affected by socially distributed memory processes and individual internal memory processes. Group identity will dynamically affect extended social memory, which affects collective memory as the background of collective identity [24]. The mimicry memory (das mimetische Gedächtnis) is concerned with human behavior (Handeln), while daily actions (Alltagshandeln) and customary customs (Brauch und Sitte) are based on the tradition of mimeticity [22]. The creator creates cultural relics through life skills, which reflects the beauty of craftsmanship and carries the ancestors’ wisdom. It is an imitation of life memories, focusing on coping. We always recall, imagine, and realistically reshape the past, so representation is the core issue of memory, and reproduction of memory is an important innovative way. Through cultural creativity, excellent cultural customs and relics are processed and integrated to highlight specific characteristics so that they not only meet the aesthetic and functional needs of modern people, but also have the imprint of unique local culture, which can extend memory. Extended memory largely depends on the interaction or coupling of an individual’s rich, dense, and external (currently mainly social) resources [25]. Social interaction can have a positive impact on extended memory [25,26,27]. In innovative design, creative design is used to create a new aesthetic model, shape a new lifestyle, and create memories that are different or even opposite to previous life experiences, while subverting memories can enhance the audience’s experience and realize brand entrepreneurship.

Imitating memory, reproducing memory, extending memory, and subverting memory are the four translation techniques designers use for cultural relics and customs. For imitating memory, the critical point is copying; tor reproducing memory, it is to replace; for extending memory it is to strengthen; and for subverting memory, it is to innovate. In cultural innovation, it can be imitated memory that is completely copied, reproduced memory that strengthens cultural attributes, or extended memory that expands and sublimates, or the completely opposite subversive memory. Collective memory is a continuous trend of thought and a kind of non-human continuity, because it only retains what is active and can survive in the collective ritual from the past. Studies have shown that vision has beneficial effects on individual memory [28,29,30]. Loveday and Conway [31] demonstrated that images are more effective at evoking memories than written records of personal experiences. Individuals can play an active role in the constructive environment, thus supporting the realization of many memory goals [24]. Long-standing social connections provide a solid connection to the distant past and help form a highly lasting memory through common memories [26]. In cultural innovation design, using the above four kinds of memory can enhance the audience’s perception of culture to obtain a pleasant interactive experience, thereby enhancing the brand’s value.

2.4. Cultural Innovation Design Analysis Mode

Shaping is the final result of the entire cultural innovation and design activities, and is the overall performance of “function and aesthetics” and “technology and human nature”. It can be seen that the shape of the product includes design elements of different proportions and the combination of factors of different proportions results in different shapes. It meets the objective requirements of science but may not meet the personal needs of human nature. In order to explore the relationship between operation interface and engineering interface, human factors engineering expert Kreifeldt [32], of Tufts University in the United States, put forward the human factors system design and analysis mode of “user—product—task” [33]. Besides the operation interface and engineering interface, a product also needs a decorative function or an aesthetically pleasing interface. The operation interface provides an easy-to-use product, the engineering interface gives a usable product, and the aesthetic interface presents a pleasant product; a balance between the three is a well-designed product. In terms of cultural innovation design, Professor Kreifeldt proposed the relationship between operational interface, engineering interface, and aesthetic interface, which is worth studying as a reference for cultural innovation design.

Culture is a way of life that was formed by a group of people who put forward life ideas (creative) under the nurturing of the culture existing at that time. Through the products of daily life, a life taste (form) was created, and the recognition of more people formed a fashionable lifestyle (ritual). The driving force of creativity is that designers extract the symbolic meaning of a particular lifestyle, convert the symbolic meaning into visual consumption symbols, and then design these consumption symbols into life products to become creative commodities. The industry is the medium to realize cultural creativity, mainly to show some life ideas, in order to form a brand, promote life taste through brand marketing, and, finally, meet consumers of a certain lifestyle with innovative products. It then continues to promote and expand implementation, so as to create a cultural and creative industry. From the perspective of culture, lifestyle is a kind of taste realized by culture, design creativity, and industry.

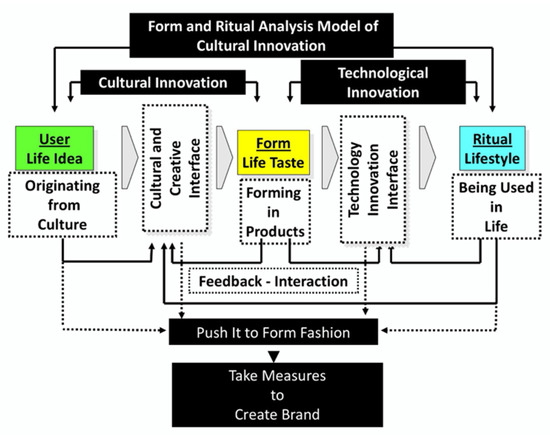

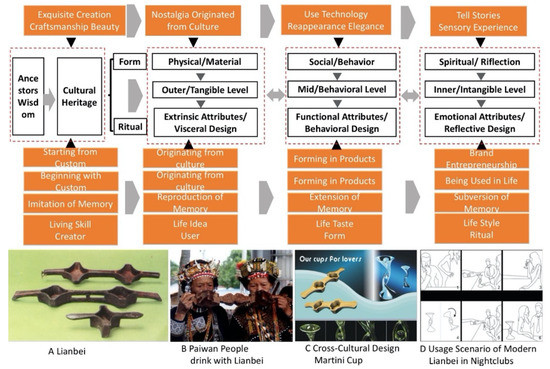

The so-called “start from culture, form in products, and use for life”, the core of the cultural and creative industry, is that craft (culture) forms business (industry) through creativity (design). How to turn craftsmanship and creativity into business is a question that the cultural and creative industry must consider. Scientific and technological innovation can affect product functions. However, the more restricted by technology, engineering, or production technology, the more restricted the freedom of form (product shape) and the composition of ritual (subjective aesthetics), and the more functional the product’s final shape will be. When the technological aspect of a product becomes more mature, the expression of cultural creativity (form) will be accessible, and the presentation of form aesthetics (ritual) will be more diverse. The final shape of the product is formed through the interaction among users, products (forms), and tasks (rituals). This is also why similar products, through different designs, will show a variety of shapes [17,34] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Form and Ritual Analysis Model of Cultural Innovation. (Redraw from [34]. Copyright 2001 Lin and Kreifeldt).

3. Research Methods

This research uses the aforementioned cultural innovation design and analysis model, based on three major parts: cultural level, influencing factors, and situational examples. The cultural level is divided into three stages: social background, product forms, and cultural rituals. From the internal, intermediate, and external levels of culture, this research is carried out on the users’ life ideas, life tastes, and lifestyles. In terms of influencing factors, life ideas come from needs, emotional responses, or inner feelings; in terms of life taste, they need a tool (form) to express this need, and the product of daily life needs to consider its usability and behavioral feelings so that there are different forms of demand. As far as lifestyle is concerned, it is not only manifested in life culture, but also a ritual outside the form.

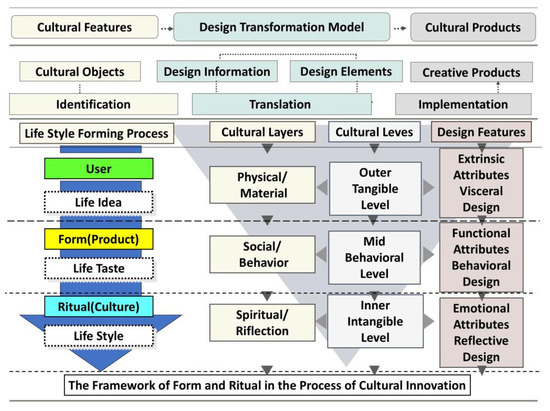

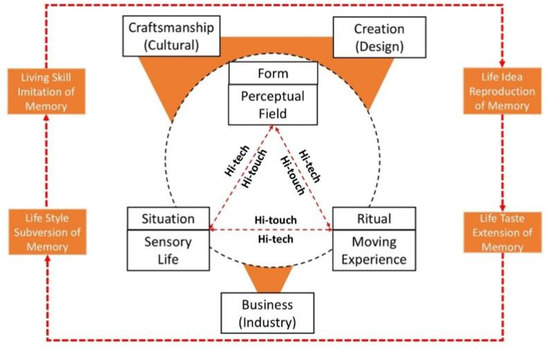

According to Rungtai Lin [35], data are raw facts; information is organized data, which is a substantive description of data; information in the context of individual role, learning behavior, and experience is knowledge. In the past, digital archives digitized the physical data of cultural relics, which were stored on the Internet and integrated into information through websites. After users access the digital archives of information for various learning, entertainment, and other activities, it will be transformed into meaningful knowledge for users. Therefore, this principle is adopted in the transformation stage of cultural innovation design, and the process of cultural innovation research is used as the basis for the user to convert from data to information to knowledge. In the process of transformation, systematic research will be carried out on the three transformation processes of data value addition, information value addition, and knowledge value addition. The corresponding application experiments of cultural innovation design will be conducted to verify that these three types of value-added activities can be used in the application mode of cultural innovation design in the future. For the correlation analysis between user (life idea) and form (product, life taste), user (life idea) and ritual (culture, lifestyle), and form (product, life taste) and ritual (culture, lifestyle), the relationship between each are shown in Figure 2 [36].

Figure 2.

Value-added Model of Cultural Innovation Design from Form to Ritual. (Redraw from [36]. Copyright 2016 Lin and Chen).

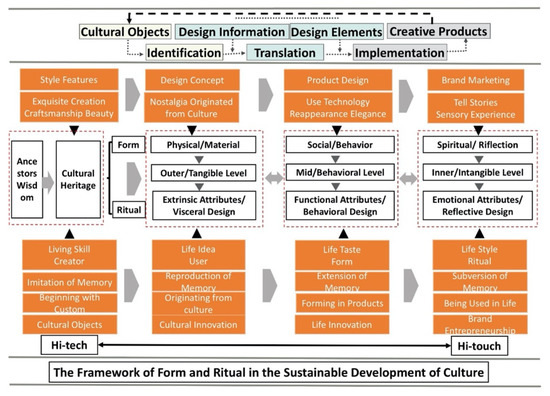

The services provided by tourism constitute experiential services, focusing on the experience of tourists when they interact, rather than just the functional benefits of the products and services provided [37]. The wisdom of our ancestors has gradually evolved into cultural heritage in the long river of history, and cultural heritage needs to be carried by tangible materials, and its cultural relics reflect the beauty of our ancestors’ craftsmanship. Through cultural relics, the aesthetic feeling of culture and art can make modern people think of the ancient times and benefit from the interpretation and communication of culture. With the addition of design, the purpose of cultural innovation is realized, and the intuitive design of external attributes is completed. While inheriting the beauty of ancestors’ culture and art, we should add modern technology to the design, strengthen the functional attributes, make it have better practical functions, and realize life innovation. At the same time, through the writing of stories, it can enhance the emotional experience of the audience, strengthen the emotional attributes, and reflect the humanistic design, so as to realize the marketing of brand entrepreneurship, better shape the culture, and add value to help the preservation and dissemination of cultural heritage. Cultural relics begin with customs, and are more imitating memories, showing the creator’s living skills; cultural creativity originates from culture. Through design, it attempts to reproduce memory and reflect users’ life ideas; life innovation takes shape in products, extends memory through the practical performance of products, and presents life taste through forms; brand entrepreneurship is used in life, through internal emotional communication and even subversion of memory, new emotional experience is obtained, and the lifestyle is shaped by rituals. In the design process, it is first necessary to analyze and identify cultural relics. After analyzing the design information, the designer translates and transforms the imitation memory with the emphasis on copying, reproduction on the replacement, extension on strengthening, and subversion on remodeling, then integrates design elements into the design process, and finally completes the design and realizes creative products. Through the transformation of forms and rituals, the completion of cultural and creative brands can bring benefits and enhance cultural transmission. At the same time, it can well protect cultural heritage with continuity, improve the economic income of local people, achieve poverty alleviation and prosperity, and bring about the sustainable development of culture and economy (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cultural Sustainable Development Model from Form to Ritual. (Redraw from [17]. Copyright 2015 Lin and Kreifeldt).

In the development of China’s civilization for thousands of years, wine has penetrated almost all social life fields. It has been determined by people with a conventional pattern, which is also one of the important pillars of food culture. The special influence of wine on people’s psychological states and the social media function of wine make wine closely related to lifestyle and other cultural phenomena, and have a profound impact on people’s lives. The wine culture of ethnic minorities has unique cultural characteristics, and behind the customs are the unique values of the aborigines. The drinking customs accumulated by ancestors and the cultural relics handed down are also valuable resources of intangible cultural heritage, which are of great value for mining local tourism resources. Yi nationality is the sixth largest minority in China, mainly distributed in Yunnan, Sichuan, Guizhou, and Guangxi Provinces; Dong people are mainly distributed in Guizhou, Hunan, Guangxi, Hubei, and other provinces; Lisu people are mainly distributed in Yunnan, Sichuan, and other places, mostly living in mountainous areas; Dulong people are one of the ethnic minorities with a small population in China (in 2021, the population was 7310, mainly distributed in Nujiang Prefecture, Yunnan Province); Paiwan people, with a population of about 60,000, are distributed in Kaohsiung, Pingtung, and Taitung, Taiwan. This study selects the Zhuanzhuanjiu (Turning wine) of Dong and Yi ethnic groups, Tongxinjiu (Concentric wine) of Lisu and Dulong ethnic groups, and the Lianbei (Continuous cup) of Paiwan ethnic groups in Taiwan as research cases. The above cases all share wine by drinking together, which not only carries the cultural memory of aborigines, but also reflects living skills and life ideas. The critical purpose of this study is to explore the sustainable development of culture from the form and ritual through the support of cultural creativity. As an intangible heritage among tangible heritage, shared national memory is vital to stimulate the close relationship between nation and culture, and can enhance their sense of national identity [38].

4. Case Analysis and Discussions

Since ancient times, wine has been the catalyst to warm people’s social activities, and it is also an indispensable drink in people’s everyday life. In daily life, wine is needed for celebrations, and also needed for sacrifices. If you are happy, you need to drink; if you are disappointed, you also need to drink. Drink when you have something to do, and drink when you have nothing to do. Common sayings such as “a thousand cups of wine are scarce for a confidant”, “the intention of the drunken man is not in the wine”, “the wine is not intoxicating but one is self-intoxicating”, and so on explain that drinking or its process is a kind of spiritual enjoyment or emotional integration. Drinking is a sacred social activity for aborigines. All ethnic groups pay great attention to drinking utensils and make appropriate drinking utensils according to the principles of customs. The interpersonal relationship shown by drinking wine together still has special significance in modern society [18,19]. Life ideas comes from life culture, based on life needs, or emotional expression, or feelings. From the perspective of cultural significance, sharing and harmony are its main ideas, and it is also the most distinctive place in the cultural connotation of drinking together.

4.1. Zhuanzhuanjiu of Yi and Dong Nationalities

Zhuanzhuanjiu is a drinking form in which several people sit around, share a wine pot and a wine bowl, and pass on the same drink in turn in a certain way. It is popular in Yunnan, Sichuan, and other places. In the southwest ethnic minority areas, it is often seen that three or five people sit around in groups in the fields, on the roadsides in front of the mountains, or in the street markets, with a wine pot and an earthen bowl containing wine in the middle. People pass the wine pot or wine bowl in a certain direction, drink a sip of wine, tell a joke; everyone gets along with others and laugh with heads tilted backward. Until the pot is empty, they bid farewell with a smile [39]. The Yi people in Liangshan, of Sichuan Province, when there are too many people and too few cups to drink, will surround themselves on the spot; each person will take a sip, pass the wine cups in turn, and drink in turn, and those who see it will have a share. Everyone will drink in moderation according to the amount of wine, and no one will drink more or less. Sometimes the wine bottle is used to drink directly, which is commonly known as Zhuanzhuanjiu. It is a kind of wine etiquette for Yi people to enhance friendship and exchange emotions. In terms of regulating the relationship between the Yi people in Liangshan, it plays an irreplaceable role in reconciling interpersonal relationships, healing spiritual wounds, comforting grief, softening or strengthening people’s will, and bonding the emotions of men and women [40].

The “Tasting New Festival” of the Dong people in Zhijiang, Hunan Province, is held every June when the early rice festival opens. Hundreds of men, women, and children in the village will form a circle around the tables and benches. Drinks and dishes are displayed on the table. This is the noblest hospitality etiquette of the Dong people—“Closing Banquet”, also known as “Hundred Family Banquet”. Zhuanzhuanjiu is the opening and final play of the closing banquet, which consists of three steps: Step 1—hundreds of people on the scene fill up the wine, and everyone holds a cup with their right hand and arms each other in a circle; Step 2—everyone sings the wine songs together and walk around the table; Step 3—turn back to the original seat, raise the cup to the mouth of the person on the right, and everyone will drink at the same time. Usually, both the host and guest should walk around the table with arm in hand for two rounds and have two drinks. The first cup turns to the right, which is called “start right smoothly left”, and the second cup turns to the left, which is called “start left smoothly right”, which means to wish the guests and hosts a happy reunion and that everything proceeds smoothly [41].

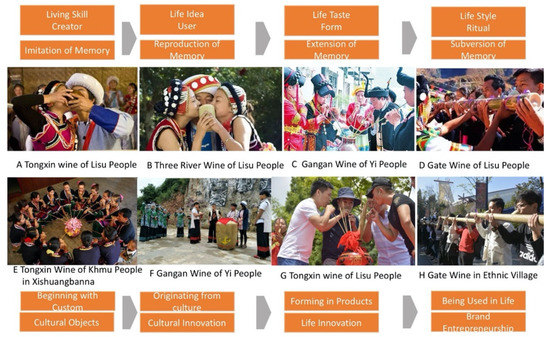

Figure 4 shows that ethnic minorities apply the traditional custom of Zhuanzhuanjiu to tourism experience projects. A and B are the traditional customs of Zhuanzhuanjiu of the Yi nationality. People sit by the stove or on the grass in a circle to share wine and promote friendship. In fact, it is the reproduction of cultural heritage customs and the imitation of memory. C and D are a turning wine for the Dong people. They place several tables together into a long strip. Everyone joins hands in a circle, sings a toast song while going around the circle, and then drink wine together, mostly indoors because this is not affected by the weather. The atmosphere is intense, originating from the unique local culture. They enrich the form and content according to their needs, allowing participants to experience life ideas and reproduce the memories of intangible cultural heritage. F and G are large-scale outdoor activities with a large number of people, commonly known as the Hundred Family Banquet. The table is in the shape of a concentric circle, which can accommodate hundreds of people at the same time, and they deeply experience the custom of drinking wine, which means reunion and completeness. According to tourism needs, the custom innovates the form, presents the taste of life, and extends the local cultural memory. E and H are innovative ways of entertaining tourists. During dinner, 4–5 local men or women, each holding a pottery bowl, pour the bowls in order from high to low as the rice wine is continuously poured. Accompanied by a toast song, the guests drink the wine in the bowl at the lowest point. Because of the continuous pouring of wine, there is a feeling of inexhaustible drinking. The form is taken from the beautiful scenery of natural mountains and flowing water, and also implies continuous friendship and blessings. This form only toasts one guest at a time. It is suitable for essential guests or when there are few tourists. It reflects the lifestyle through ritual and boldly creates and subverts the traditional memory. Tourists have shaped the brand characteristics in the in-depth experience.

Figure 4.

Tourism Experience Conversion of Zhuanzhuanjiu Wine. (Source: this study).

4.2. Tongxinjiu of Lisu and Dulong Nationalities

Tongxinjiu is a crucial way for the Lisu people in Yunnan Province to eliminate contradictions and estrangements, and to communicate interpersonal relationships and feelings. The two share a bowl of Tongxinjiu, the primary method to connect feelings, enhance friendship, and eliminate estrangement. When old friends meet, they cross their arms and tie their necks, and drink a bowl of wine in one gulp, and their emotions are deepened; when boys and girls drink Tongxinjiu, their life together will be determined; when friends have suspicions or conflicts, after drinking a bowl of Tongxinjiu, old enmities and new resentments will melt away [42]. Tongxinjiu reflects Lisu’s warm and bold national character, shows Lisu’s deep affection for their relatives and friends, and implies “one heart and one mind”. At present, there are about six ways to drink Tongxinjiu: the first way is Yahabazhi (stone moon wine). When drinking, people stand around the table, holding a wine cup in their right hand and holding a friend or guest in their left hand. The shape resembles a full moon. After the toast song, everyone drinks the wine together, reflecting solidarity, respect for friends, and sincerity. The second way is Sannizhi (three rivers flowing together in wine). Three people put their left hands together and close to each other. The cup on their right hand winds anticlockwise to form the shape of Jinsha River, Lantsang River, and Nujiang River, symbolizing the three people working together to create a better future. The third way is Rankazhi (warrior wine). This comprises the “strong see off wine” sent by the elders to the warriors and the “welcome wine” for the warriors to return in triumph, which means that they have incomparable courage and determination to overcome all difficulties. The fourth way is Puhuazhi (fortune wine). Two people cross their cups and hook each other’s wrists. At the same time, they hold each other’s hands with their hands and their lower limbs also cross. The number eight is formed up and down, implying the excellent wish for success and wealth. The fifth way is Sijiazhi (missing wine). Two people face to face, with their right hands around each other’s neck and their left hands supporting each other’s back, or holding their shoulders and face close to each other’s face and their mouths close together, drink together at the same time, implying “one mind”. The sixth way is Rishizhi (longevity wine). When honoring the elders, the younger generation holds the wine cup with both hands and kneels in half. The cup should be lower than the elder’s cup. They clink the cup and drink together, reflecting their respect for the elderly [43].

During a wedding ceremony for people of Yunnan Dulong nationality, the parents of both sides of the marriage hand the couple a bowl of rice wine. The bride and groom take it with both hands, hold the bowl, and drink it with their faces close to each other. It is known as Tongxin wine, which symbolizes never separating and growing old together. At the wedding ceremony of the Bulang people in Mojiang, a bottle of watery wine is placed on the table, with two curved bamboo poles inserted in it. The bride and groom drink wine together, wishing that they love each other and grow old together. In addition, the custom of newlyweds drinking together also exists among Wa, Bai, Jingpo, Achang, Pumi, and other ethnic minorities. When the Lahu people get married, the bride and groom should drink a bowl of clear water together, indicating that their hearts are pure and the husband and wife are of one mind and will grow old together [44].

Figure 5 shows the conversion mode of the tourism experience of Tongxinjiu. The pictures show two, three, and then many people drinking together. Whether there are two, three, or many people, the common point is that they all use the wine from the same utensil. A: Two people drinking together, with most pairs being couples, lovers, relatives, and friends. They can enhance their feelings by drinking together, which reflects unity. Between lovers, it also implies growing old together, imitating memory through customs. B: Three people drinking together is based on the metaphor of the Jinsha, Lantsang, and Nujiang rivers in nature, and natural harmony refers to emotional harmony, which originates from the cultural reproduction of memory and reflects cultural creativity. C and F: GanganJiu (rod wine) is shared by many people. Multiple hollow thin bamboo rods are inserted into the pot, with many people forming a circle and drinking together at the same time. Drinking together implies one mind. E: Khmu people in Xishuangbanna, Yunnan Province, place a pottery pot wine in the middle. People sit down and form a circle and each person takes a bamboo pole, with many people drinking together at the same time. Through innovative forms, the memory of traditional culture is extended. D and H: Lanmenjiu (gate wine) is an innovative form. It is usually set at the entrance of the village or at the door of the house. Tourists will be stopped and local women will present wine vessels made of long and thick bamboo. Several small bamboo branches are arranged on the bamboo as openings. When drinking, many people are in a row side by side and operate harmoniously. They drink together during the toast song to experience the hospitality of the local people, and also feel the beautiful meaning of concentric wine. The whole process has a strong sense of ritual, breaking the traditional form of two or three people drinking together in an in-depth experience, adopting the way of subverting memory to shape the lifestyle and strengthen people’s understanding of the local culture.

Figure 5.

Tourism Experience Conversion of Tongxin Wine. (Source: this study).

4.3. The Lianbei of Paiwan People in Taiwan

Taking the drinking utensils of the Paiwan ethnic group in Taiwan, using the Lianbei as an example, through the discussion of aboriginal life culture, this paper attempts to understand the cultural connotation (life idea) of the Lianbei, how to measure the harmony (life taste) of its operation when used by two people, and how to show the shared culture (lifestyle) in life with the Continuous cup. It is speculated from the relevant literature that Paiwan people have the habit of drinking a cup of wine together in their daily life, which later evolved into a form of special drinking cups, and then formed a cultural ritual in their lifestyle. The process is shown in Figure 6. The Continuous cup is mostly used in weddings, ceremonies, or tribal festivals. The two people who are drinking must operate harmoniously at the same time to complete the drinking action. It not only connects each other’s friendship, but also conveys the warmth and harmonious feeling between people. Drinking utensils have cultural connotations of form and ritual in tradition. In addition to the cultural connotations of Paiwan cups, it is worth studying the evolution from traditional single drinking utensils to interesting two-person drinking utensils [17,18]. Lianbei is a life product design that expresses the harmony of human nature by Taiwan aborigines. In addition to the shape of the Lianbei, the size of the human body needs to be considered, while its operation must also comply with human factors engineering. It can reproduce the spiritual enjoyment in the process of drinking or achieve the emotional integration of drinkers. This kind of life utensil is full of humanity and wisdom, and is what modern life products lack.

Figure 6.

Creative Design of the Continuous Cup. (Source: this study).

The significance of the Lianbei in the Paiwan nationality is to convey the meaning of friendship. In the modern nightclub culture, it is also through drinking to make friends. Therefore, the cultural meaning of friendship conveyed by the Lianbei has been transformed into a modern life culture with nightclubs as the background—the Martini cup is an interpretation of the modern nightclub dating culture and echoes the original cultural connotation of the Lianbei [17,18]. In Figure 6, C is the Martini cup designed by Yanting Guo, Yipei Zhang, and Mingxian Sun from the Institute of Craft Design, National Taiwan University of Arts, who won the Golden Prize in the Pompeii Martini Cup Design Competition in Taiwan and participated in the international competition in Italy on behalf of Taiwan. The design concept is to transform the original horizontal side-by-side-linked cup into a vertical symmetrical form, and add the cultural meaning of the aboriginal-linked cup to the traditional form of the Martini cup, which is a typical cross-cultural design of the cultural exchange between the East and the West. This combination of traditional and modern dating mediums allows people to make friends decently and unrestrictedly in the environment of nightclubs, through the cups that symbolize friendship. The usage scenario is shown in Figure 6. The overall shape shows a well-conceived sense of design, expressing the texture and artistic sense of the medium through glass, and giving full play to the spirit of Taiwanese local craftsmanship. From the cultural point of view, the sharing is the unique character in the shape and meaning of the cup. Therefore, the design team started brainstorming according to the characteristic of sharing, and classified many words similar to sharing, including the connection of heart and hand, the connection of heart and mind, the connection of heart and heart, the integration of mind and matter, in pairs and couples, the killing of two birds with one stone, the pairing of two, the exchange of emotions, the one hundred years harmony, and so on. From the stirring words, the design team believes that emotional communication is a phrase that can express the figurative and abstract connotations of the cup. Therefore, emotional communication is further considered as the development direction of design. From the relationship between drinking and emotional communication, it is outlined that nightclub culture can fully express this characteristic, that is, make friends through drinking and then achieve the effect of emotional communication, joy, and relaxation, and indirectly echo the Lianbei of Paiwan people which conveys the cultural meaning of friendship, sharing, and celebration among ethnic groups.

4.4. Discussions

In this research, three case studies were used to examine the role of intangible cultural heritage and sustainable development. Through research, it can be seen that in tourism activities, people have shifted from the pursuit of Hi-tech (functionality, rationality, and high technology) to the pursuit of Hi-touch (high feeling, human nature, and touching experience) [17]. It can be seen in the system of wine, people, and environment that the process-oriented dialogical and place-specific is the basis of the evolution of design form [16]. Through the analysis of drinking together by different ethnic groups, it is found that there are commonalities in the drinking culture of different ethnic minorities, including: (1) Carrying shared values; (2) Embodying the character traits of simplicity, enthusiasm, and interaction; (3) Paying attention to the communication mode of joint cooperation; (4) Presenting a life attitude of harmonious coexistence with nature.

Through the cultural characteristics of drinking together, the designer allows tourists to stimulate their interest and improve their cognition in the interaction between form and ritual through on-site viewing, interaction, tasting, and other personal experiences in ethnic minority areas, so as to finally share a moving experience and complete the dissemination of culture. Figure 6 shows how designers master the cultural connotation, and the creativity of cultural and creative commodities through starting from customs, originating from culture, forming in products and being used in life, and through imitation of memory, reproduction of memory, extension of memory, and subversion of memory, to show the connection between intangible culture and modern life through memory in the process of cultural creativity.

How to improve emotional cognition in interactive experience is the focus of designers’ consideration. Based on the model of sustainable experience design for local revitalization [45] and the analysis of the above three cases, this study proposed a framework of sustainable experience design from the perspective of the aesthetic economy from form (Hi-tech) to ritual (Hi-touch), as shown in Figure 7. It can be supported to create a perceptual field, provide a moving experience, and construct a sensory life from the three aspects of form, ritual, and scene, so as to turn the unique culture in the intangible cultural heritage into a business through creative design, in order to achieve sustainable development of the cultural industry.

Figure 7.

Sustainable Experience Design Model of Intangible Cultural Heritage. (Redraw from: [45]. Copyright 2022 Yang, C. H. et al.).

The intangible cultural heritage in ethnic minority areas is the accumulation of the long-term life of the aborigines, with a long history and unique aesthetics. The costumes, food, architecture, religious beliefs, life concepts, and values of ethnic minorities have their own characteristics, which have unique attraction and mystery to the experience of tourists. These cultural characteristics are also vital to attracting tourists to participate in in-depth experiences. The rich intangible cultural heritage in ethnic minority areas is a precious resource with substantial value and significance in promoting the local tourism industry. When tourists watch, understand, and participate in various activities, they better understand the language, song and dance, architecture, clothing, diet, life concept, and folk skills of ethnic minorities. At the same time, local intangible culture continues to gain value in tourism, which can make local aborigines pay more attention to their own culture and encourage them to explore, protect, and inherit their unique cultural memory. Due to the influence of cultural adaptation and assimilation, foreign tourists will have specific destructive effects on local culture and environment, so it is necessary to integrate the value of local culture into development [46]. Protection must follow the living protection principle and cultural memory logic. Improvement and innovation should be reasonably designed to reflect the subject’s value orientation and stimulate the participant’s cultural identity. It should comply with the principle of cultural aesthetics. In order to increase attraction and entertainment, it is also necessary to create some new forms of activities [47]. A noteworthy issue is that with the entry of a large number of foreign tourists, people from different places will also allow local aborigines to gain more exchanges and contacts. How to avoid the damage and impact of foreign cultures and values on local aborigines is a significant issue. At the same time, sufficient attention should also be paid to how to avoid the damage of foreign tourists to the local environment. Precise and prudent methods should be taken, and these are worthy of further study.

5. Conclusions

This research selected three case studies with the theme of ethnic minorities drinking together. From the perspective of the interaction between form and ritual in cultural innovation, it proposes the design framework of form and ritual in cultural innovation, discusses how to reproduce the cultural connotation of drinking together in modern life, and is even used in the development of cultural and creative products to become daily necessities. The life idea of drinking together demonstrates the core values of its cultural meaning–harmony and sharing. According to this idea, the life taste of drinking together is developed. This form requires the drinkers to operate harmoniously at the same time in order to complete the drinking action. Finally, it has become fashionable to form a lifestyle. People can share wine on different occasions. Fine wine not only helps people to connect but also conveys the feeling of warmth and harmony between them. The model constructed in this study is mainly used to apply intangible cultural heritage to the development of innovative products. It focuses on how to make people know, understand, and love their cultural meaning through creative design and the interaction between form and ritual in order to achieve the goal of sustainable development and promote sustainable development of cultural industries in ethnic minority areas.

Through this research’s case studies, the effectiveness of the construction model is verified. However, only three cases were selected due to the limitations of objective conditions. Whether the model is reliable in the sustainable development of the intangible cultural heritage of ethnic minorities in other countries and regions needs further verification.

Author Contributions

Each author contributed to the paper. Conceptualization, J.W. and Y.L.; methodology, L.-H.J. and P.-H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.L.; supervision, P.-H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support for this research provided by the General Projects of Shenzhen Philosophy and Social Science Planning under Grants, No. SZ2022B037; and Shenzhen University Young Teachers’ Scientific Research Launch Project, No. 860-000002112001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Rungtai Lin and Lijuan Guo.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McAreavey, R.; McDonagh, J. Sustainable Rural Tourism: Lessons for Rural Development. Sociol. Rural. 2011, 51, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- James, A.; Bansilal, S. Indigenous knowledge practitioners’ sustainable livelihood practices: A case study. Indilinga Afr. J. Indig. Knowl. Syst. 2010, 9, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Labadi, S.; Giliberto, F.; Rosetti, I.; Shetabi, L.; Yildirim, E. Heritage and the Sustainable Development Goals: Policy Guidance for Heritage and Development Actors; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Streimikiene, D.; Svagzdiene, B.; Jasinskas, E.; Simanavicius, A. Sustainable tourism development and competitiveness: The systematic literature review. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Xiao, G.; Xu, W.; Xie, Y. An Analysis of Tourists’ Perception Difference and Travel Demand of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in Guilin. Areal Res. Dev. 2014, 33, 109–114, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.R. Religion of the Semites; Meridian Books: New York, NY, USA, 1957; p. 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, G. Heritage as a driver for development—Its contribution to sustainable tourism in contemporary society. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS 17th General Assembly, Paris, France, 27 November–2 December 2011; pp. 496–505. [Google Scholar]

- Jokela, T.; Coutts, G.; Beer, R.; Din, H.; Usenyuk-Kravchuk, S.; Huhmarniemi, M. The Potential of Art and Design to Renewable Economies. In Renewable Economies in the Arctic; Natcher, D., Koivurova, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 62–80. [Google Scholar]

- Huhmarniemi, M.; Kugapi, O.; Miettinen, S.; Laivamaa, L. Sustainable future for creative tourism in lapland. In Creative Tourism: Activating Cultural Resources and Engaging Creative Travellers; Duxbury, N., Albino, S., Pato Carvalho, C., Eds.; Cabi International: Wallingford, UK, 2021; pp. 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, S. Beyond authenticity and commodification. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K. Living pasts: Ontested Tourism Authenticities. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singgalen, Y.A.; Sasongko, G.; Wiloso, P.G. Ritual capital for rural livelihood and sustainable tourism development in Indonesia. J. Manaj. Hutan Trop. 2019, 25, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.P. Authenticity and sincerity in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D.; Healy, R.; Sills, E. Staged authenticity and heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronis, A. Coconstructing Heritage at the Gettysburg Storyscape. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 386–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhmarniemi, M.; Jokela, T. Arctic art and material culture: Northern knowledge and cultural resilience in the northernmost Europe. Arct. Yearb. 2020, 2020, 242–259. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, R.; Kreifeldt, J. Do Not Touch—A Dialogue between Design Technology and Humanity Arts; NTUA: New Taipei City, Taiwan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, R. Transforming Taiwan aboriginal cultural features into modern product design: A case study of cross-cultural product design model. Int. J. Des. 2007, 1, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, R. Designing friendship into modern products. In Friendships: Types, Cultural, Psychological and Social; Toller, J.C., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, M. Das Kollektive Gedächtnis; S. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1985; pp. 34–77. [Google Scholar]

- Nora, P. Zwischen Geschichte und Gedächtnis; S. Fischer: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1998; pp. 11–42. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, J. Das Kulturelle Gedächtnis: Schrift, Erinnerung und Politische Identität in Frühen Hochkulturen, Vol. 1307; CH Beck: Munich, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.B. Cultural Memory, Tradition Renewal and Heritage of Traditional Festivals. J. Renmin Univ. China 2007, 1, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Smart, P. Extended memory, the extended mind, and the nature of technology-mediated memory enhancement. In Proceedings of the 1st ITA Workshop on Network-Enabled Cognition: The Contribution of Social and Technological Networks to Human Cognition, Baltimore, MD, USA, 22 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, J.; Harris, C.B.; Keil, P.G.; Barnier, A.J. The psychology of memory, extended cognition, and socially distributed remembering. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 2010, 9, 521–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnier, A.J.; Sutton, J.; Harris, C.B.; Wilson, R.A. A conceptual and empirical framework for the social distribution of cognition: The case of memory. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2008, 9, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sutton, J. Remembering. In Cambridge Handbook of Situated Cognition; Ayded, M., Robbins, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, E.; Kapur, N.; Williams, L.; Hodges, S.; Watson, P.; Smyth, G.; Srinivasan, J.; Smith, R.; Wilson, B.; Wood, K. The use of a wearable camera, SenseCam, as a pictorial diary to improve autobiographical memory in a patient with limbic encephalitis: A preliminary report. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2007, 17, 582–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, A.R.; Pauly-Takacs, K.; Caprani, N.; Gurrin, C.; Moulin, C.J.A.; O’Connor, N.E.; Smeaton, A.F. Experiences of Aiding Autobiographical Memory Using the SenseCam. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2012, 27, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crete-Nishihata, M.; Baecker, R.M.; Massimi, M.; Ptak, D.; Campigotto, R.; Kaufman, L.D.; Brickman, A.M.; Turner, G.R.; Steinerman, J.R.; Black, S.E. Reconstructing the past: Personal memory technologies are not just personal and not just for memory. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2012, 27, 92–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveday, C.; Conway, M.A. Using SenseCam with an amnesic patient: Accessing inaccessible everyday memories. Memory 2011, 19, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreifeldt, J.G.; Hill, P.H. Toward a theory of man–tool system design applications to the consumer product area. Proc. Hum. Factors Soc. Annu. Meet. 1974, 18, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Kreifeldt, J.; Hung, P.-H.; Chen, J.-L. From Dechnology to Humart—A Case Study of Taiwan Design Development. In Cross-Cultural Design Methods, Practice and Impact; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Kreifeldt, J.G. Ergonomics in wearable computer design. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2001, 27, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R. Preface—The Essence and Research of Cultural and Creative Industries. J. Des. 2011, 16, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-L.; Chen, S.-J.; Hsiao, W.-H.; Lin, R. Cultural ergonomics in interactional and experiential design: Conceptual framework and case study of the Taiwanese twin cup. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 52, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Sotiriadis, M.; Zhang, Y. The Influence of Smart Technologies on Customer Journey in Tourist Attractions within the Smart Tourism Management Framework. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.Y. Shared national memory as intangible heritage: Re-imagining Two Koreas as One Nation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 520–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. Wine Culture and Health; Yanbian People’s Publishing House: Yanji, China, 2009; pp. 122–123. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Z. An Analysis of Wine Culture of the Yi Nationality in Liangshan. J. Southwest Univ. Natl. Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 1999, 20, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. Chinese Folk Songs and Customs; Shanghai Music Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2016; pp. 450–453. [Google Scholar]

- He, M. On Minority Wine Culture. Ideol. Front. 1998, 12, 69–72, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, M. Singing at the Moment Must Be Drunk: Wine Culture Volume; Beijing University of Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2013; pp. 163–165. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, M. The Symbolism of the Traditional Food Culture of Yunnan Minorities. Ethn. Art 2010, 3, 41–46, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.-H.; Sun, Y.; Lin, P.-H.; Lin, R. Sustainable Development in Local Culture Industries: A Case Study of Taiwan Aboriginal Communities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottyn, I. Livelihood trajectories in context of repeated displacement: Empirical evidence from Rwanda. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, K. Countermeasures for Tourism Development of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Ganzi Prefecture. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2012, 6, 565–569. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).