Abstract

Food waste remains an ongoing problem in hotel operations, and changing employees’ behaviour is key to tackling this issue. Analysing the influences on employees’ working practices can help to drive pro-environmental behaviour changes that reduce food waste, thus supporting the UN’s SDG 12: ensuring responsible consumption and production patterns. This study used the theory of planned behaviour as its theoretical framework and empirical data generated through participant observation, analysis of organisational documents, and semi-structured interviews in luxury hotels to examine waste drivers among employees. The findings suggest that hotel workers adopt a rational rather than moral lens toward food waste. Moreover, attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control strongly influence intentions to perform pro-environmental behaviours. Positive attitudes and strong subjective norms propel employees toward pro-environmental behaviours while a lack of perceived control acts as a constraining force.

1. Introduction

Food waste has been recognized as one of the prime global challenges of the 21st century [1]. The topic has become a significant policy issue due to increased recognition of the negative social, economic, and ecological impacts of waste generation and disposal. Though it is difficult to quantify food waste, research has estimated that 1.3 billion tonnes of food waste are produced every year [2]. This amounts to between 30–50% of global food production output (ibid). Wastage of edible food drives global food [in]security [3], and it is difficult to justify, in the present climate, when global food production systems are already under strain, owing to the rapid rise in human population as well as declining soil health [4]. Food waste also places additional demands on the wider food system [5]. Natural resources are expended in growing, harvesting, transporting, processing, and storing food products. With wastage of food, precious natural resources, such as water and energy, are lost and, when inappropriately disposed, food waste produces potent greenhouse gases [6,7]. Consequently, the social and environmental impacts of food waste are not limited to the loss of food. Despite this increased recognition, the waste of edible food has continued unabated. This is true for domestic provisioning as well as commercial foodservice businesses [8].

The hospitality sector, which encompasses a variety of foodservice operations, either as standalone units or as supporting components of larger organisations, including in hotels, has often attracted criticism for wastefulness in its operations and for making significant contributions to overall food waste [9,10]. For instance, it has been estimated that the British hospitality sector alone produced 1.1 million tonnes of food waste annually [11]. This represented approximately 12% of total food waste in the country and, in financial terms, was valued at £3.2 billion. Moreover, research has suggested that around 75% of food waste generated by the hospitality sector was avoidable [11]. Consequently, there remain significant opportunities for preventing waste from arising. In addition, previous research estimates that in the hospitality and food service sector, preparation waste accounts for 45% of overall generated food waste [12]. This is significantly higher than waste attributable to spoilage or plate waste. This indicates inefficiencies within production practices and stresses that employees’ attitudes and behaviours have a central role to play if waste minimisation efforts are to succeed. It is widely agreed that waste prevention is of critical importance for hotels, in particular, for public relations, economic, environmental, marketing, legal, and ethical reasons. Despite this, the problem of food waste in hotels has received limited attention in the academic literature and much of the work has focused on consumers rather than employees [8,13,14,15,16,17].

Many scholars have contended that human behaviours contribute to current socio-environmental problems [18,19,20]. Hence, the study of behaviours that may affect the environment positively has gained traction [21]. Pro-environmental behaviours (PEBs) can be defined as those that minimise damage to the environment, at the very least, or may benefit it [22]. Employees’ pro-environmental behaviour (ePEB) was defined as ‘any action taken by employees that she or he thought would improve the environmental performance of the company’ [23]. Hotels often rely on members of staff to enact PEB voluntarily as these are rarely formalised in job descriptions [24]. Hence, further understanding of the drivers of hotel employees’ PEB in different contexts is needed. Much scholarly work has been devoted to studying PEB in private and public settings. However, given the variation in work and workplace scenarios, studies of PEB within diverse employment environments are needed to expand the evidence base [17,25,26]. In a similar vein, studies examining staff attitudes and behaviours are only gradually emerging [17,27,28,29,30,31,32]. These studies have primarily focused on employees’ perceptions on the issue, their motivations and personal norms. Some take a general approach in examining the causes and drivers of waste, while others focus on certain types of hotels (all-inclusive, for instance) or generational cohorts (Gen Z, in particular). Previous research has established that the effectiveness of behavioural interventions generally increases when they are specifically directed toward antecedents of behaviours [22]. Despite that, the prime drivers of food waste prevention within hospitality work settings remain under-researched and poorly understood [33,34].

This paper contributes to this body of knowledge by examining dispositional factors that influence employees’ PEB in luxury hotels. Luxury hotels offer a unique and compelling context to study PEB change because demanding brand standards and customer expectations drive service provision, often at the expense of environmental objectives [34]. Moreover, the study adopts the theory of planned behaviour as its conceptual framework [35], within a qualitative empirical strategy, which is capable of producing context sensitive insights into lived experiences that shape antecedents of behaviours, cf. [29]. The research context, conceptual focus, and empirical strategy thus help to ensure that the findings of this study can support the strategic decisions of hospitality operators seeking to encourage sustainable practice through PEB change.

2. Literature Review

The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) has been widely applied within environmental studies [35]. The fundamental premise of TPB is that all human behaviours are rational [36,37]. Hence, an individual is likely to perform PEBs because they believe the outcomes to be beneficial for themselves. Proponents of TPB thus contend that self-interest is a (if not the) core driver of PEB.

The TPB approach recognises that social and dispositional forces interact to influence behaviours. Behaviours are shaped by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control (PBC). Moreover, TPB postulates that these drivers collectively create an intention within an individual to act, which can then lead to the behaviour itself. Within the TPB model, the intention to act is the critical and immediate predictor of behaviour.

Attitude has been defined as ‘the degree to which a person has (un)favourable evaluation or appraisal of the behaviour in question’ ([35], p. 188). Individuals assess the likely consequences of their behaviour, placing greater value on particular outcomes, and hence favouring these over others. The perceived consequences, labelled as outcome beliefs, shape the attitude toward the specific behaviour. In the present context, an individual’s attitude toward food waste is shaped by two distinct constructs. These are the actor’s beliefs toward said behaviour (i.e., whether wasting food is a problem) and the value they assign to the outcome (i.e., whether engaging in waste prevention efforts is worthwhile in light of the perceived investment).

There is broad agreement in the literature that attitude is one of the strongest drivers of ePEB [38,39,40]. A recent study tested the impacts of attitudes in determining waste prevention behaviour outcomes. The research concluded that people who held either positive attitudes toward waste prevention or negative attitudes toward wasting food tend to throw less food away [41]. Another study examined attitudes of Generation Z hospitality employees [28]. The findings suggested that young hospitality employees carry positive attitudes toward waste prevention and/or negative attitudes toward wastage. Both were likely to lead to less waste because individuals tended to enact behaviours that were consistent with positive attitudes and avoided actions toward which they carried negative attitudes. Given the salience of attitudes in guiding behaviours, the following research question has been proposed:

RQ1: What are hospitality managers’ and employees’ attitudes toward food waste?

PBC refers to actors’ evaluations of how easy or difficult it may be to enact certain behaviours [35]. In light of PBC, employees also assess whether they have the capabilities to perform said behaviours [42]. Based on these two factors, employees make choices about orchestrating their efforts. Past research has conceptualised PBC as self-efficacy or problem-efficacy because it is commonly understood to rely on actors’ self-evaluation of whether they believe that they possess adequate resources, skills, and knowledge to perform behaviours [35,43].

Previous research has suggested that employees sometimes did not engage with PEB at work, because they sensed that their choices were limited by strictly defined organisational policies [44]. This may also apply to the corporate hospitality sector as work practices are often governed by management and enforced through standard procedures, policies, and training. A prime example is the use of standard recipes that are widely used in corporate hotel companies and commercial kitchens. Likewise, menu design is often controlled by management teams that are remote from hotel operations. Consequently, operational staff may feel restricted in their ability to engage in PEBs, even when they have strong positive attitudes toward them. Other scholars have added weight to this argument, noting that employees viewed reducing food waste as a difficult challenge [28,45]. Food waste prevention initiatives demanded time, extra effort, and often required deliberate, conscious changes in behaviour. Based on these discussions, the following research questions were formulated:

RQ2: How do perceptions of control over individual work routines influence employees’ behaviours toward waste prevention?

RQ3: What are the constraints toward waste prevention encountered by hospitality employees?

Subjective norms can be conceived as the ‘perceived social pressure [exerted by] significant reference persons to perform or not to perform a behaviour’ ([36], p. 16). This approach is built on the assumption that human society should be seen as being organised through social networks [46]. Consequently, actors consider certain individuals important and therefore value their opinion over those of others. Perceptions of how such influential people may judge their actions was likely to have a significant impact on whether people chose to enact or reject behaviours. Subjective norms drive behaviours in several ways. First, the actor may fear that a specific behaviour may provoke negative social outcomes, including disapproval or sanctions. Second, they may wish to enhance their social identity, for example, by belonging to a certain group [46]. Evidently, subjective norms are guided by the individual’s perceptions of how others expect them to behave. Within workplaces, colleagues form a central reference group [47]. This is especially relevant in hotel kitchens where employees are required to work in interdependent units, and shared organisational practices are visible to other team members. For example, a recent study demonstrated that subjective norms can operate within hotel kitchen teams and exert pressure on employees to minimise waste [48]. Research Question 4 focuses on the influence exerted by social norms:

RQ4: What roles do referent group practices play in influencing employees’ food waste creation/prevention behaviours?

The review of the literature revealed that organisational researchers have examined environmental issues more generally and food waste specifically in the hospitality sector. However, previous research mainly focused on analysing food production systems and waste quantification mechanisms, alongside the impacts of regulations and other interventions [13]. However, drivers of ePEB have remained under-researched [49,50].

3. Methods

3.1. Study Context, Strategy, and Sampling

The research used a multiple case study strategy [51] and the fieldwork was conducted according to constructivist paradigmatic principles, with a relativist ontology and subjectivist epistemology [52]. This position avoided positivist assumptions that reality is fixed and common for everyone, and it rejected empirical imperatives to reduce human behaviour to measurable variables. In contrast, the study used a multimethod qualitative approach to examine organisational actors’ subjective realities within their everyday work settings. This sought to generate a rich contextual understanding of employees’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours. Data were collected in several organisational subunits (i.e., various departments related to food, such as procurement, receiving, storage, production, service (both buffet and a la carte), and waste disposal). The case study company explored multiple strategies to reduce food waste and provided access to hotels in two different countries. This was not a comparative study; nevertheless, studying different empirical settings enabled us to consider diverse situational factors. Moreover, the common focus and methods adopted in both contexts were used to create a rich ‘composite’ data set, which consequently helped to identify a variety of operational and institutional factors that drove food waste and shaped the potential for waste reduction [34,48].

The case organisation is a world-renowned international hotel chain, with hundreds of properties across the globe. Primary data were collected from two of their luxury hotels, one in Germany and the other in the United Kingdom. Focusing on one category of hotel operation allowed the phenomenon to be analysed within its context. Furthermore, five-star hotels have been known to produce more food waste than lower category ones [53]. The two case study hotels were comparable in terms of size and nature of services provided as well as star classification (both hotels were rated five stars). Food-handling practices were similar, driven by brand standards and organisational policies, which were consistent across the two sites. Including two sites allowed for a greater depth of investigation, since it was possible to observe emerging patterns across the empirical sites [51]. Data were collected over eight months and at various temporal points to capture differences in employees’ behaviours over time.

Criterion sampling was employed to select the case study hotel company [51,54]. The following four criteria were used: the company (a) had an established system for reporting their sustainable performance, (b) could provide basic data on the quantities of food waste created, (c) procured food using a centralised and disciplined buying system, and (d) provided access for the researchers to collect data. Numerous hotel companies that met the first three criteria were identified, but the selected case study company was open to collaboration and provided access to their units, thus also meeting the fourth criteria. This was especially important as the research team needed to spend significant time on site interviewing employees and observing their workplace behaviours. Hence, a hotel company that was open to inquiry that could be deemed disruptive to operations was ideally suited. The case study company could be considered a typical case within the international luxury hotel sector.

Purposive sampling was used to identify the most relevant people to engage in the study [51,54]. Based on the essential criterion of information richness, members of staff who controlled or influenced food inputs at the case study hotels were selected. Respondents from various levels of the organisation were invited to participate in the study. Previous studies have endorsed this approach, arguing that it was important for case study researchers to select a sample that took into account significant divisions of labour and responsibility within organisations [27,30,53]. Employees at management levels, including directors, general managers, head chefs and cost controllers were included in the sample. Data were also collected from employees in supervisory roles (such as restaurant supervisor, back of house supervisor, sous chefs, and junior chefs). In addition, general level employees (such as service staff, commis, and kitchen porters) also took part in the study. This sampling approach, which included employees from all levels and from across the food system, generated various, often contrasting views and therefore provided balanced insights into the topic.

3.2. Data Collection Methods

Corresponding to other organisational case study research, primary data were collected using participant observation and analysis of organisational documents, in conjunction with group and individual semi-structured interviews [51]. Various documents were examined to establish a deeper understanding of the business context and standard operational practices. Corporate operational documents shed light on company policies and procedures, which were compared and contrasted with observations of employees’ behaviours in the workplace. A wide range of documents were analysed, including those pertaining to company-wide policies (such as social responsibility reports and the corporate food waste strategy), site level management (menus, standard recipes, list of suppliers, and purchase and waste disposal invoices) and operations (inter- and intra-departmental communications and food waste collection data).

To encourage respondents to express their views and opinions freely, open-ended questions were asked about food-related practices in the workplace. The semi-structured format also enabled interviews to explore unanticipated, emerging themes in detail [55]. Interview questions were initially guided by key themes identified through the literature review. For example, questions were asked about food waste in general and people’s attitudes on the topic. A number of questions probed how food waste arises within the food cycle, which helped to understand the social context and constraints that may have discouraged people from adopting PEBs. In addition, follow-up questions were guided by the flow of discussions. Sixteen formal one-on-one interviews were conducted, each typically lasting between 45 and 60 min. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed manually. It was evident that many respondents were less guarded and spoke freely before and after the recording was done. Therefore, naturally occurring conversation was noted with the permission of the respondents. The interview schedule has been included in Appendix A.

Group interviews examining food production and service practices offered valuable opportunities to gather additional data [53]. Altogether, three group interviews were conducted, covering an additional eleven respondents. The interviews were audio-recorded with permission from the respondents. Subsequently, they were manually transcribed. Manual transcription was favoured as we also noted important cues, such as long pauses, pitch, and tone of respondents’ voices. The transcribed scripts were 243 pages long.

A member of the research team played the role of ‘observer as participant’ in the case sites [56]. Observations were overt and unstructured. Routine, mundane actions and interactions pertaining to food handling and waste were noted in the observation log. Furthermore, non-verbal communications and critical incidents were noted. Beyond helping to capture people’s behaviours, in situ observations gave the researcher opportunities to ask follow-up questions from interviews and to probe further about observed practices. Observations thus provided unique, context-sensitive insights into dispositional drivers of employees’ behaviours and the actions reported in interviews could be reassessed in light of observational data.

3.3. Data Analysis

Primary data were analysed through a reflexive thematic approach [57]. In the spirit of the study’s constructivist position, the analysis sought to identify rich, subjective insights from the data rather than reducing it to a mechanistic, quantification of words and phrases [52,57]. The significance of different data was determined through the researchers’ interpretation in relation to the research questions. To start with, transcripts were read multiple times; this provided a general sense of respondents’ perspectives. Open coding helped to order the initial interpretation of findings, some of which were common to the two case study hotels, while many others were unique. Examples of codes created at this stage were brand standards, food safety, infrastructure, management support, and training.

Open coding was followed by focused coding, where some of the initial labelling and coded data were rejected for one of two reasons. First, the coded data did not align with the overall objective of the study (for example, level of unionisation and customer education). Second, it was not sufficiently connected to the issues identified in the wider data set (for instance, sharing of food products and staff briefings). Where necessary, multiple codes were assigned to the same data set. Subsequently, initial themes were developed; these were guided by the literature review and codes were assigned to the themes. Examples of initial first-order themes were dispositional factors, organisational factors, external environmental factors, social agents, and non-human agents, to name a few. The themes were reviewed, refined, and (re)named. For the purpose of this paper, data associated with the three key areas—attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural control—were (re)examined in detail and the relevant findings were reordered for discussion in this context.

Data and methodological triangulation were employed to support trustworthiness of the findings and their interpretation. Similar to other qualitative organisational case study research, data generated through document analysis, participant observation, and interviews were reassessed in relation to each other [51]. This allowed us to challenge or explain the findings and assumptions. Interview questions were often guided by observed behaviours. Likewise, during observation, the research team kept records of whether employees’ behaviours were consistent with the hotel company’s environmental policy. Data generated from the two empirical case sites were combined in the final analysis. This synthesised analysis stage helped to identify converging and diverging themes and issues across the two cases. In addition, different respondents’ viewpoints were compared and contrasted. This helped to ensure that the subjective experiences and realities of major stakeholders were faithfully represented [52].

4. Findings

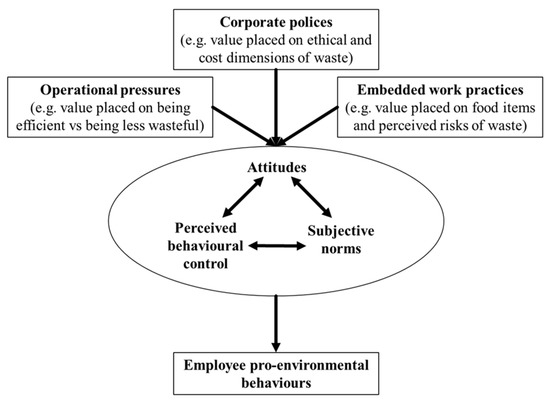

The study’s findings are summarised in Figure 1. The data highlighted three aspects of organisational practice that influenced waste creation and reduction: corporate policies, operational pressures, and embedded work practices. These, in combination, helped to determine staff’s dispositions toward performing pro-environmental behaviours in relation to food waste. The findings thus consider how these factors potentially shaped staff’s attitudes, perceived behavioural control, and subjective norms.

Figure 1.

Factors shaping dispositions toward pro-environmental behaviours.

4.1. Attitude

Organisational documents indicated that the prevention of food waste was a central concern at a corporate level for the case study hotel company. Many initiatives were directed toward reusing or recycling food waste at both case study sites. However, these appeared to have variable impacts on staff’s attitudes and ultimately their pro-environmental behaviour. Senior management attitudes toward food waste prevention appeared positive. However, their attitudes appeared to be driven primarily by the financial implications of wastage. For example:

Chefs will give that [waste prevention] a lot of attention because it ultimately affects his costs and what he purchases, whether it is under the headline of food waste, it is more about his food gross profits; but yes, absolutely, directly affects food waste.(Director of Operations, UK)

We are looking at it from the cost perspective. Food waste at the end is food cost. The costs urge us to really look active to our buffet, prevent food waste at the end. Controlling your food cost actively means that everything you do, you influence waste. The target is not reduce waste, no, target is control your cost. Waste is one part of that.(Director of Operations, Germany)

Potential cost savings by preventing waste from arising drove positive attitudes toward it, cf. [13,28]. However, the cost-driven, rational approach divided respondents, as many reported negative attitudes toward waste prevention when the financial outcomes were not lucrative enough and savings were outweighed by the effort involved. With this reasoning, sous chefs working at operational levels rationalised wastage of cheaper food items.

You cannot not have food ready. Curry and rice are cheap anyway, so we will have these ready in bulk, but the meats etc., we will batch cook.(Junior Sous Chef, UK)

Eggs is not so expensive, so this is where we can say, okay it’s not bad like if we have to throw those six away and make six new ones.(Sous Chef, Germany)

Moreover, many reported negative attitudes toward waste prevention in general.

We are working on that [food waste prevention] but the difficulty with that is we all have the day job to do as well, so we are sometimes having to park our day jobs to try and focus on that… and to find that window in your day job to sort of focus on that, because otherwise you are sort of doing it half-heartedly, and you will find that we do things half-heartedly even with the sustainability project.(Head of Sustainability, UK)

But the point is, many things, especially regarding waste is something which is like ‘in the way’, which is annoying. Even for me as well, and to add more stuff [to my work], this is just annoying.(Sous Chef, Germany)

The data suggest that many employees expressed strong, negative attitudes toward waste prevention, suggesting that they were less inclined to engage with PEB. Moreover, perceived lack of penalties for waste also drove negative attitudes, further propelling employees away from adopting PEBs. The Assistant Head Chef in the UK noted,

They [general level employees] think it’s like too much pressure, just dump it, nothing will happen.

Previous studies reported that employees’ PEB was significantly different at work than at home [28]. However, the findings of this study offered a contradictory view. Respondents who reported positive attitudes toward waste prevention revealed that their behaviours were consistent and that they made a conscious effort to minimise waste from arising at home as well as work.

TPB postulates that individuals’ attitudes concern a specified behaviour. The findings of this study indicate that respondents who enacted behaviours that could help to minimise waste also performed various other PEBs, such as recycling. The findings from this study thus help to stress that pro-environmental attitudes are not discreet entities, but may instead form clusters that become embedded over time within individuals’ mental makeup. It can be argued that individuals who hold positive dispositions toward one PEB are more likely to engage in other such behaviours.

I am actually somebody, I do pride myself on not throwing lot of food away, I do tend to buy food that is produced in the region if I can, I try to buy seasonal things, ermmmm… I just was throwing my garbage out this morning and I don’t throw away a lot of food. I freeze food if I can’t eat it.(General Manager, Germany)

At home, we don’t just cook like that. We now measure the rice, we measure the meat or dal, and we cook only what we require. Apart from [that], in my home, we don’t use plastic, all glass storage. And, we make a list [for] buying… I buy what I need, if it’s not in the list, I don’t buy(Assistant Head Chef, UK)

Surprisingly, many respondents affirmed that their own attitudes toward this issue had shifted through the interactions they had with colleagues.

…[O]thers don’t care—I myself am demoralised now. Such initiatives must be driven by the management; I simply cannot see any interest. The kitchen team will simply disregard food waste prevention by saying that ‘we don’t have the time’. They will give you excuses such as food hygiene, but the reality is that it is down to extra work, and nobody sees this as their job.(Waitress, Germany)

…[A]fter a while, I get bored of telling people. How many times? It’s like talking to a wall, 3–4 times to the same guy, you get bored and don’t care anymore. I am going mad and going back home in a bad mood, and I think—you know what, I don’t care anymore. Do what you like.(Supervisor—Back of House, UK)

Previous research observed that attitudes could be influenced through various social interactions [58]. The findings of the current study echo those findings, highlighting that respondents’ attitudes toward PEBs were influenced by embedded practices in the workplace [58]. Primary data suggest that attitudinal transfer might be experienced by (a) actively interacting with others or (b) passively interacting with others by simply observing others’ behaviours. This implies that attitudes themselves are not static but fluid. Many respondents identified a shift in their own attitudes. Importantly, participants frequently agreed that their positive attitudes transformed into negative ones, and therefore, they stopped engaging in PEB. None of the participants reported experiencing that positive pro-environmental attitudes had ‘rubbed-off’ on them within the social nexus of workplace practices. This finding invites examination in future research.

4.2. Perceived Behavioural Control

There was broad agreement among respondents that their choices to combat the waste of food were limited. Hence, wastage was generally viewed as an unavoidable consequence of corporate policies and the pressures caused by their operational implementation [28,34]. The perceived lack of control over their own actions acted as a prime barrier that dissuaded hotel staff from embracing PEB at work. Respondents reported that their sense of control was stronger in domestic settings. Therefore, they voluntarily performed actions that led to waste reduction at home, using their judgement and creativity. However, they felt unable to do so within the commercial kitchen environment. Surprisingly, the perceived absence of control was equally applicable to management as well as general level employees.

In the home environment, I don’t see it [using up leftover foods] as taking a chance… I know when something is safe to eat and when it’s not. But in a hotel environment, where you have paying customers coming through the door, you cannot take any sort of risk.(Director of Operations, UK)

They [employees] are increasingly asking the question—why can’t we take it to the homeless? But we can’t due to legalities involved, health and safety etc.… Food has been out on the buffet for two hours—we all say it is a shame, as people will take it, but the legalities etc.(Food and Beverage Supervisor, UK)

Employees’ (perceived) lack of control regarding waste prevention behaviours was fuelled by multiple factors that shaped corporate policies, operational pressures, and working practices. For instance, stringent food safety laws in Europe governed whether certain food products could be (re)used or not. Moreover, due to the exacting quality standards of luxury hotels, food products that had lost their visual appeal or those that had passed ‘best before’ dates were considered unusable. With the aim of ensuring consistency in food quality, workplace practices were standardised across the chain and reinforced by procedures such as standard recipes. Consequently, general-level kitchen employees were often not empowered to perform PEB voluntarily. This inflexible, corporatized approach to food handling was evident from the German Director of Operations’ statement.

I guess not really [there is little interest in engaging with waste prevention] because they are feeling not empowered to influence… they need to buy certain products, they need to use it in a certain way, because we decide how this is displayed, how does the buffet look like.

Individuals’ beliefs about the relative ease or difficulty of performing certain behaviours have been seen as key drivers of PBC [35,59]. Rational choice perspectives suggest that people are more likely to perform behaviours viewed as simpler and requiring less effort. The chefs highlighted that behaviours related to food waste prevention were difficult to perform:

Food is so dynamic… Maybe the guest takes too much, maybe somebody makes mistake producing it, or someone uses new one and not the old one because they don’t see it or the fridge is not good in design, ermmm… then you produce so much waste but you don’t really know where it has come from. Or have they produced too much? You can’t know these things easily.(Sous Chef, Germany)

It [food handling practices] needs to be documented from start to finish, documentation—these guys are cooks, they are not scientists. If you really want to do it [waste prevention] properly, if you really wanna do a kitchen from start to finish, in a full HACCP way, it takes a lot of time and a lot of energy.(Head Chef, Germany)

Interviewees recognised that food-handling practices created added operational pressures. In addition, behaviours directed at waste prevention were viewed as ‘extra work’. Given that waste prevention demanded additional time and effort over and above normal responsibilities, those behaviours were judged difficult to perform. Such perceived difficulties may explain employees’ reluctance to engage with preventative behaviours. Therefore, waste prevention behaviours were less attractive to employees and such perceptions may have shaped their attitudes. In sum, the data suggest that perceived lack of control negatively influenced employees’ behaviours. The findings also show that people’s perceived sense of control was stronger within domestic, personal spaces in comparison to work. This suggests that the impacts of a perceived lack of control over one’s own behaviours were amplified within workplaces and may have acted as instrumental constraints to the organisation’s efforts to mobilise PEB.

4.3. Subjective Norms

Managers understood the power of subjective norms and actively projected those pressures on employees through internal marketing and the communication of corporate policies. A UK-based chef explained how subjective norms could exert pressure on the individual to engage with waste prevention through everyday work practices.

I can immediately think of two or three of my staff who have a real concern about it, who will admonish their colleagues if they are wasting. If I see a chef who has a misguided technique, I will correct them as my sous and demi chefs will do. There was this one day when I went in there and there was a load of tomato tops that they had been slicing, and I did say to them—you know, you can take another one or two slices off each.

At the same time, employees responded to the pressure and complied with the expectations of management and colleagues. This was found to be the case when their own attitudes were not necessarily aligned with the behaviour they were asked to perform. A sous chef based in Germany exemplified this point.

This [waste separation for recycling] is what the management wants me to do and I agree on doing it, so this is like a contract we made… they pay me for do this, also to put all the waste in the right bins, I don’t care if it’s effective or it’s good, I just do what then comes the order [from management], [I] make sure it’s done [emphasis in original].

Thus, subjective norms could serve as important social factors helping to mobilise ePEBs. Although commercial kitchens may be organised in sections, food preparation involves a great degree of teamwork. Hence, kitchen practices are shared and individuals’ food-handling behaviours are visible to others in the team [5]. For that reason, social risks, such as disapproval, were high. Perceived social risks were even higher in these empirical contexts where many PEBs have been normalised, becoming embedded in everyday lives. Prime examples of such PEBs are waste separation and recycling. Many employees attempted to exert pressure on colleagues by role modelling PEBs. Role modelling and contagion led to stronger subjective norms as these helped to establish normative behavioural codes. A UK-based supervisor explained.

I also try to act as a role model and try to sell the idea [of waste prevention] to them. I feel I need to lead by example, simple lip service won’t work.

Previous research suggested that of the three dispositional drivers of behaviours included in TPB, subjective norms showed the weakest correlation to intention [60]. The findings of this study suggest that subjective norms could influence workplace behaviours and are therefore potentially more relevant than previously thought. The salience of subjective norms in relation to other volitional factors could therefore be examined further in future work.

Past research has indicated that subjective pressures are indirect and implicit [60,61]. The findings of this study challenge this view, as members of staff were direct and explicit in their efforts to establish normative codes of conduct. This was found to be the case at both case study hotels. It can therefore be argued that subjective norms and, by extension, normative pressures could be strengthened directly through verbal communication and indirectly through deliberate activities. The actions of chefs in the UK illustrated this.

I will make them get the food out of the general bin and put it in the food bin, and some of them will roll their eyes.(Junior Sous Chef, UK)

A junior chef placed too many celery sticks on the cheeseboard. The senior simply took a few away without saying anything to the apprentice.(Observation Log, UK)

Subjective pressures without a doubt had a strong influence on PEB. However, it must be acknowledged that PEBs driven by subjective norms may simply be tokenistic and not truly reflective of individuals’ attitudes or environmental concerns.

5. Discussion

Many respondents viewed waste prevention through a financial lens, rather than a moral one. Furthermore, they assessed the merits of waste prevention against risks to the experiential proposition and to their professional identities [34]. In other words, hotel employees approached food waste issues from a pragmatic-rational perspective. This challenges existing perceptions on this subject, as many commentators view this issue as one concerning ethics [28,62].

The findings are compatible with core assumptions of behavioural economics, suggesting that financial agendas rather than concern for the environment may drive ePEB. Interestingly, this approach has been strongly supported by others who found that restaurant managers were more likely to engage with waste prevention when they were actively aware that it could lead to cost savings [8]. However, the current study offers a more nuanced perspective as the cost-based approach only propelled employees to engage with waste prevention when the savings were perceived to be significant. Hence, such an approach to waste prevention, fuelled primarily by commercial motives, may have limited impacts. This approach toward PEBs is therefore questionable and needs further examination.

This study’s findings also suggest that the lack of PBC might serve as a severe constraint. This may be particularly important in workplace environments because employees may not always be able to enact behaviours that are consistent with their attitudes. Employees may be unable to prevent food going to waste due to organisational policies, which are shaped by wider legal and food safety concerns. Consequently, operators may try to rationalise wastage by treating it as a normative outcome of routine hospitality operations. A lack of PBC may further strengthen negative attitudes toward waste prevention. Echoing other recent studies in the hospitality sector, this suggests that a key management imperative should be to remove perceived barriers, ensuring that employees feel empowered to enact meaningful PEBs in their everyday working practices [63].

Subjective norms are intertwined in the social organisation of everyday life, and they have the potential to contribute to food waste generation and reduction in hospitality contexts [29]. ePEBs may be strongly influenced by perceived normative pressures and not necessarily by positive attitudes. Additionally, some behaviours may be seen as reflections of the team’s overall performance and capabilities. For example, food cost is typically calculated at an aggregate level for an entire kitchen. Hence, subjective pressures to comply with normative behaviours are embedded in kitchen working cultures [5,48]. Subjective norms that drive waste prevention may thus be strengthened by human resource management practices aimed at positive social outcomes that recognise and reward individual achievements in relation to group successes. These can help to build one’s social identity and reinforce positive attitudes that normalise food waste related PEBs and embed them in shared work practices.

The findings suggest that the three dispositional factors depicted in TPB collectively and directly influence intentions to enact PEB. Individual as well as social factors have a key role in driving ePEB. TPB acknowledges that the relative salience of attitudes, subjective norms, and PBC might vary across situations [64]. This paper contributes to the existing knowledge in suggesting that, within workplace contexts, subjective norms and PBC may have a relatively stronger influence on driving or restricting ePEB. Furthermore, attitudes, subjective norms, and PBC are inextricably linked to each other. Consequently, a deeper understanding of the interplay between these three forces and how they influence one another is needed to design interventions that can effectively achieve PEB change toward food waste reduction.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study are relevant for any hospitality enterprise aiming to encourage their employees to engage with pro-environmental initiatives. Managers can play a pivotal role in encouraging PEB change. This can be achieved by harnessing the power of subjective norms. Managers can establish stronger subjective norms through enacting PEB themselves and consciously projecting themselves as role models. Furthermore, local advocacy can foster PEB change among employees too. Therefore, organisational opinion leaders should be recognised and given a suitable platform to perform the role of ‘environmental champions’. Such initiatives may also result in a gradual shifting of attitudes that help to galvanise PEB change.

Furthermore, the findings suggest that weak PBC can counteract positive attitudes, thereby dissuading employees from engaging in PEB. Employees do not feel empowered to make decisions and enact PEBs at work on a voluntary basis. Businesses wishing to engage employees in PEB will benefit from finding mechanisms to empower employees, particularly by allowing increased flexibility in standard work routines. Flexible and empowered performance can be embedded in recognition and reward systems that acknowledge and reinforce positive behaviours. Moreover, such reward processes may themselves be enrolled in wider systems and cultures that promote training to help foster stronger feelings of self-efficacy, which feed into positive behaviours, individually and at the group level.

Finally, the findings suggest that pro-environmental attitudes exist in clusters. This may inform recruitment practices in the hospitality industry as candidates may be selected based on their ecological attitudes. Individual recruitment, tied to a wider attempt to engineer a team or collective culture of responsible behaviour, may consequently be a more effective strategy for enacting responsible behaviour related to food waste and other environmentally constructive initiatives.

7. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

The current research lacks a longitudinal perspective since access to the case study hotels was provided for a specific timeframe. For that reason, ethnographic research is recommended, since it can help to further examine the salience of dispositional factors within the specified context of waste prevention. Furthermore, primary data were collected from luxury hotels and the findings may therefore not be applicable to other types of hospitality businesses. Despite their intention to enact behaviours, some employees may be unable to do so due to external factors, such as lack of infrastructure. Therefore, intentions may not always translate into actual behaviours. The role of external forces and how they interact with dispositional factors is worth investigating.

The primary data for this study were collected in Germany and the UK, so the findings arguably reflect predominantly Western European attitudes toward the topic. Future research conducted in diverse cultural contexts can potentially lead to unique findings that account for the role of different customs, traditions, and ways of life. For instance, conceptions regarding the edibility of food are socially constructed. The influence of cultural norms regarding waste can be examined in cross-cultural studies. Demographic factors may also shape people’s attitudes toward environmental issues. These are also important aspects of ePEB deserving further study.

Author Contributions

G.C.: conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, visualisation, and project administration. P.L.: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, visualisation, and supervision. R.H.: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, writing—review and editing, and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Oxford Brookes University (Ref: 160998).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to a confidentiality agreement with the participating organisation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Interview Schedule

- What is food waste in your opinion?

- To what extent is food waste seen as an area of concern in the hotel?

- What are the specific policies/procedures in place at the unit level to address this challenge?

- In your view, what are the main reasons owing to which food ends up being wasted in routine operations of the hotel?

- Tell me about your experience of food waste management in this organisation. What initiatives have been tried in the past?

- Could you talk me through some of the other behaviour change initiatives that have been implemented in the hotel in the past? What was done and how?

- What was the outcome of such initiatives?

- What is the role of procurement/receiving/storage/kitchen/service departments in pre-venting food waste?

- Who are the key people involved and how?

- Tell me about your interactions with other departments. Is food waste something that is often discussed and communicated?

- What are the future plans to address this challenge (training, infrastructure provision, measuring food waste)?

- Any other comments or feedback that you think might be relevant to this research?

References

- Morone, P.; Koutinas, A.; Gathergood, N.; Arshadi, M.; Matharu, A. Food waste: Challenges and opportunities for enhancing the emerging bio-economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. Foreword. In Food Waste Management: Solving the Wicked Problem; Närvänen, E., Mesiranta, N., Mattila, M., Heikkinen, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; p. V. [Google Scholar]

- Närvänen, E.; Mesiranta, N.; Mattila, M.; Heikkinen, A. Introduction: A framework for managing food waste. In Food Waste Management: Solving the Wicked Problem; Närvänen, E., Mesiranta, N., Mattila, M., Heikkinen, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- The Guardian. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2012/aug/26/food-shortages-world-vegetarianism (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Hennchen, B. Knowing the kitchen: Applying practice theory to issues of food waste in the food service sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organisation. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i6583e.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Russell, S.; Young, C.; Unsworth, K.; Robinson, C. Bringing habits and emotions into food waste behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principato, L.; Pratesi, C.; Secondi, L. Toward zero waste: An exploratory study on restaurant managers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malefors, C.; Callewaert, P.; Hansson, P.A.; Hartikainen, H.; Pietiläinen, O.; Strid, I.; Strotmann, C.; Eriksson, M. Toward a baseline for food-waste quantification in the hospitality sector—Quantities and data processing criteria. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Filimonau, V.; Nghiem, V.; Wang, L. Food waste management in ethnic food restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waste Resource Action Programme. Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Progress_against_Courtauld_2025_targets_and_UN_SDG_123.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Waste Resource Action Programme. Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-10/WRAP-Overview%20of%20Waste%20in%20the%20UK%20Hospitality%20and%20Food%20Service%20Sector%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Dhir, A.; Talwar, S.; Kaur, P.; Malibari, A. Food waste in hospitality and food services: A systematic literature review and framework development approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Juvan, E.; Grün, B. Reducing the plate waste of families at hotel buffets–A quasi-experimental field study. Tour. Manag. 2020, 80, 104103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Coteau, D. Food waste management in hospitality operations: A critical review. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Juvan, E.; Qiu, H.; Dolnicar, S. Context-and culture-dependent behaviors for the greater good: A comparative analysis of plate waste generation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1200–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T. Reducing food waste behaviour among hospitality employees through communication: Dual mediation paths. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 1881–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druckman, J.; McGrath, M. The evidence for motivated reasoning in climate change preference formation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmental concern. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Vlek, C.; Steg, L. Human behaviour and environmental sustainability: Problems, driving forces and research topics. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.S. Environmental concerns and food consumption: What drivers consumers’ actions to reduce food waste? J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2019, 31, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.; Steger, U. The roles of supervisory support behaviours and environmental policy in employee eco-initiatives at leading edge European companies. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 605–626. [Google Scholar]

- Pichel, K. Enhancing ecopreneurship through an environmental management system: A longitudinal analysis of factors leading to proactive environmental behaviour. In Sustainable Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Wüstenhagen, R., Hamschmidt, J., Sharma, S., Starik, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2008; pp. 141–196. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, R.; Johnson, E. Energy use, behavioural change and business organisations: Reviewing recent findings and proposing a future research agenda. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 195–208. [Google Scholar]

- Blok, V.; Wesselink, R.; Studynka, O.; Kemp, R. Encouraging sustainability in the workplace: A survey on the pro-environmental behaviour of university employees. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 106, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnasr, A.E.A.; Aliane, N.; Agina, M.F. Tackling food waste in all-inclusive resort hotels in Egypt. Processes 2021, 9, 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.; Jie, F. To waste or not to waste: Exploring motivational factors of Generation Z hospitality employees toward food wastage in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 80, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.; Okumus, B.; Jie, F.; Djajadikerta, H.G.; Lemy, D.M. Managing food wastage in hotels: Discrepancies between injunctive and descriptive norms amongst hotel food and beverage managers. Br. Food J. 2022. Ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B. How do hotels manage food waste? Evidence from hotels in Orlando, Florida. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B.; Taheri, B.; Giritlioglu, I.; Gannon, M.J. Tackling food waste in all-inclusive resort hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, M.; Bilska, B.; Tul-Krzyszczuk, A.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Estimation of the scale of food waste in hotel food services—A case study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicarelli, V.; Aluculesei, A.; Lagioia, G.; Pamfilie, R.; Bux, C. How to manage and minimise food waste in the hotel industry: An exploratory research. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 16, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, G.; Lugosi, P.; Hawkins, R. Food waste drivers in corporate luxury hotels: Competing perceptions and priorities across the service cycle. Tour. Hosp. 2021, 2, 302–318. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. The norm-activation model and theory-broadening: Individuals’ decision-making on environmentally-responsible convention attendance. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, M.; Han, H.; Holland, S. The determinants of hospitality employees’ pro-environmental behaviours: The moderating role of generational differences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, S.; Peters, G.Y.; Kok, G. Energy-related behaviours in office buildings: A qualitative study on individual and organisational determinants. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 61, 227–249. [Google Scholar]

- Oefi, K.; Werther, M.; Thomsen, J.; Holst, M.; Rasmussen, H.; Mikkelsen, B. Reducing food waste in large scale institutions and hospitals: Insights from interviews with Danish foodservice professionals. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2015, 18, 502–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, T.; Marsh, E.; Stunell, D.; Parry, A. Spaghetti soup: The complex world of food waste behaviours. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gist, M.; Mitchell, T. Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1992, 17, 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, F. Developing an integrated conceptual framework of pro-environmental behaviour in the workplace through synthesis of the current literature. Adm. Sci. 2014, 4, 276–303. [Google Scholar]

- Ruepert, A.; Keizer, K.; Steg, L. The relationship between corporate environmental responsibility, employees’ biospheric values and pro-environmental behaviour at work. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Choi, Y. Hotel employees’ perception of green practices. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2013, 14, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrandias, L.; Elgaaied-Gambier, L. Others’ environmental concern as a social determinant of green buying. J. Consum. Mark. 2014, 31, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlebois, S.; Creedy, A.; von Massow, M. Back of house–focused study on food waste in fine dining: The case of Delish restaurants. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 9, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, G.; Lugosi, P.; Hawkins, R. Evaluating materiality in food waste reduction interventions. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2020, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Grün, B.; Dolnicar, S. Biting off more than they can chew: Food waste at hotel breakfast buffets. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ture, R.; Ganesh, M. Understanding pro-environmental behaviours at workplace: Proposal of a model. Asia-Pacific J. Manag. Res. Innov. 2014, 10, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschan-Piekkari, R.; Welch, C. (Eds.) Rethinking the Case Study in International Business and Management Research; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. The Constructivist Credo; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri-Fenech, M.; Sola, J.; Farreny, R.; Durany, X. A snapshot of solid waste generation in the hospitality industry. The case of a five-star hotel on the island of Malta. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 21, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- King, N. Using interviews in qualitative research. In Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organisational Research; Cassell, C., Symon, G., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2004; pp. 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, P.A.; Adler, P. Membership Roles in Field Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health and Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 843–860. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, A.; Van Der Werff, B.; Henning, J.; Watrous-Rodriguez, K. When do recycling attitudes predict recycling? An observation of self-reported versus observed behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 38, 262–270. [Google Scholar]

- Elshaer, I.; Sobaih, A.E.E.; Alyahya, M.; Abu Elnasr, A. The impact of religiosity and food consumption culture on food waste intention in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lo, S.; Peters, G.; Kok, G. A review of determinants of and interventions for pro-environmental behaviours in organisations. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 2933–2967. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Rios, C.; Demen-Meier, C.; Gössling, S.; Cornuz, C. Food waste management innovations in the foodservice industry. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karatepe, T.; Ozturen, A.; Karatepe, O.M.; Uner, M.M.; Kim, T.T. Management commitment to the ecological environment, green work engagement and their effects on hotel employees’ green work outcomes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Barbera, F.; Ajzen, I. Control interactions in the theory of planned behavior: Rethinking the role of subjective norm. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).