1.1. Research Background

With the rise of mobile devices and their integration into various aspects of our lives, including personal banking and powerful apps, people are increasingly relying on them to manage their daily activities. Bittman et al. [

1] noted that mobile phones have rapidly become one of the most widely adopted devices in recent technological revolutions. As a result, near-field communication (NFC) mobile payment environments, which facilitate transactions via smartphones, are gaining popularity. However, from a business owner’s perspective, do NFC mobile payments offer a competitive advantage or create operational challenges in fast-paced environments? Empirical research on the impact of NFC environments on small business performance, particularly in the food and beverage industry, is limited. Nevertheless, more and more customers are accustomed to making payments with their mobile devices. The majority of current research focuses on examining the influence of mobile payment on customer satisfaction [

2], intention [

3], or loyalty [

4]. Limited research has explored the effects of NFC mobile payments on restaurant performance from the perspective of restaurateurs. Thus, this paper’s key contribution stems from its integration of the overarching innovation diffusion theory (IDT) model with the technology acceptance model (TAM). This integration aims to analyze how the NFC mobile payment environment influences the operational performance of restaurants (ROP) from the restaurateurs’ viewpoint.

The World Health Organization (WHO) suggested that global consumers adopt contactless payment modes. This further helped raise the mobile payment transaction rate and boosted contactless payment modes [

5]. Nowadays, two major technological layers, NFC and barcode, are on the market as contactless communication technologies for mobile payment. NFC-based payments outperform barcode-based payments in terms of security, usability, and convenience [

6]. The NFC mobile payment is estimated to be

$4.8 billion in 2015 and is expected to reach 47.42 billion by 2024 [

7]. This demonstrates the increasing importance of NFC in the era of smartphones. Advanced environments are emerging, facilitating the installation of NFC mobile payment. Mobile phones have become a convenient and preferred platform for various activities, surpassing traditional desktop computers. The maturation of cloud computing, smartphone technology, and communication advancements has propelled the rapid adoption of mobile payments worldwide, replacing cash and credit cards [

8]. The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated the adoption of mobile payments as consumers sought safer payment methods, leading to a surge in usage even after lockdown measures were lifted [

9]. Reports suggest that non-cash transactions, including mobile application-based transactions, are expected to increase from 17% in 2021 to 28% in 2026, driven by endorsements from the business and retail sectors. These sectors recognize the advantages of mobile payments, such as cost reduction and increased consumer spending on products and services [

10].

However, The Wall Street Journal [

11] reported that mobile payment operators have observed a lack of compelling reasons to encourage small-business retailers to adopt mobile payments so far. Among the factors deterring merchants from embracing mobile payments, there are technological incompatibility, complexity, the investment costs involved, and the absence of sufficient critical mass and knowledge in this domain [

12]. Nonetheless, Begonha et al. [

13] suggested that NFC mobile payment environments can offer a convenient and cost-effective alternative for merchants who do not typically accept credit card payments. Researchers have also proposed that the food and beverage industry can enhance customer loyalty and satisfaction by implementing technology-driven models that improve quality, efficiency, and the service–profit chain for performance growth [

13,

14].

1.3. Mobile Payment Environment Definition and Literature Review

Au and Kauffman [

15] defined a mobile payment environment as a mobile device initiating authorization for payments and confirming the exchange of value for goods and services. Mallat [

16] defined it as conducting funds transfer or payment transactions with a mobile device, either through a third party or direct payment to the receiving party. Ghezzi et al. [

17] recapped the concept of a mobile payment environment as an electronic payment procedure in which at least one part of the transaction is conducted using a mobile phone capable of securely handling a financial transaction over a mobile network, or via various wireless technologies, such as NFC or Bluetooth. Mobile payment environments can be divided into remote payments and short-range NFC payment contactless technologies [

14]. The technology and platforms used by these two forms of payment are different. A remote payment environment is an e-commerce online transaction, in which consumers use their mobile phone to make payments and complete the shopping procedures on the Internet through credit cards, IC cards, or electronic coupons. The NFC payment environment uses a mobile phone as the payment tool, which is used in a physical store to complete the payment transaction in a connected or offline mode [

18]. NFC lets two devices positioned at a very short distance from each other exchange data. Both devices ought to be equipped with an NFC chip [

19]. Some scholars have already recognized NFC as the future trend in mobile payment environments [

20]. This is because the advantages of the NFC environment are low power, accessibility, and simple communication equipment [

21]; also, NFC technology does not require complex device pairing. Therefore, it provides many benefits to food and beverage operators and consumers [

22,

23]. Hayashi [

24] pointed out that the environment using NFC mobile payment is 15 to 30 s faster than usual card swiping. This is because the time spent on the NFC device is in short, simple operating method and secures message transfer; this type of payment technology is most convenient and suitable for fast-paced restaurants and travel environments [

21,

25]. Getz and Robinson [

26] also mentioned that it is possible to use NFC mobile payment environment to raise consumer satisfaction towards the restaurant. Slade et al. [

27] argued that mobile-payment-related research is still in its early stage, even though there has been a relative increase in mobile payment research over the past few years [

28]. However, as compared to the extensive e-commerce research (e.g., online bank, mobile bank, etc.), the mobile payment environment is a relatively new area of research [

29], with most of the research focused on the consumer perspectives [

30,

31,

32,

33]. There are quite rare studies to understand the environment that merchants use for mobile payments and the method they acquire to implement this new payment vehicle [

34]. Not to mention that little research examines the influential factors in the mobile payment environment from the restaurateurs’ perspective [

35].

1.4. The Impact of Mobile Payment Environment on Operations Performance

Niedritis et al. [

36] indicated that effective business processes ensure the achievement of the enterprise’s goals. The performance measurement should be performed from different perspectives. Performance is the extent to which the organization’s goal is achieved [

37]. To meet an organization’s goal and to create the organization’s value, an organization needs to establish a performance measurement scheme and create a revenue-generating environment. Fredendall and Robbins [

38] believe that the purpose of an organization’s existence is to achieve its predetermined goal, performance is to measure the extent to which the organization’s goal is achieved, and managing performance is thus the achievement rate for a business’s strategic goal. Organizations effectively make an empowering environment, or latently adapt to the environment through asset distribution; the methods taken to accomplish the association’s objective are an essential record to survey if a business activity has been fruitful [

39], i.e., the mission of the manager of a business is to develop an environment that increases organizational performance and creates maximum efficiency with the least investment. Qiu [

40] believes that the subject of performance evaluation is not an individual of the organization; it should be the overall organizational performance. Performance evaluation is the systematic process of how an organization achieves its goals.

There are different perspectives on performance measurement indicators among different scholars. The objective measurement using secondary data for listed companies is one commonly used method. Miller and Friesen [

41] proposed various performance evaluation indicators, including investment returns, cash flow, market share stability, price-to-book ratios, and employee productivity. Woo and Willard [

42] suggested that there are 14 types of performance measurement indexes, including investment returns, sales returns, sales income, cash flow, investment, etc. Walker and Ruekert [

43] used three indexes, financial performance, growth, and profitability, as benchmarks to measure the overall operations performance of a company. Richard and Johnson [

44] suggested that objective measurement of business performance could use employee turnover rate, employee productivity, and return on equity as a basis.

The second perspective for performance measurement is using subjective assessment, commonly for unlisted small-and-medium enterprises. Gunday et al. [

45] brought up the survey method in performance measurement. Moideenkutty et al. [

46] highlighted that the use of questionnaires could reflect respondents’ feelings, which are the subjective performance measurement. Amin et al. [

47] also used the questionnaire method as the subjective measurement of business performance. The subjective measurement method as compared to the objective measurement method enables a higher probability to receive more information about the organization they served [

46,

47]. Due to the fact that this research sample focused on unlisted restaurants, the ROP used the questionnaire for measuring business performance, as proposed by Gunday et al. [

45].

1.5. Theoretical Model and Research Hypotheses

Pal et al. [

48] used a keyword searching method to review a total of 50 pieces of literature about the mobile payment environment and mobile banks in recent years; most of the papers attempted to utilize a theoretical model to investigate the determinants of consumers’ intentions of mobile payment. Kim et al. [

49] claimed that it would be better to use TAM than the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) proposed by Venkatesh et al. [

50] as a theoretical basis for research about mobile payment environments. Andersson [

51] also pointed out that most research used these two theories, TAM and IDT, to explore the drivers of consumers’ uses for new information technology environments.

Davis [

52] developed the TAM theory to explain the decision-making factors in accepting an information technology environment, with a particular focus on technology use behavior. The implication is that the individual level of willingness to accept the new technology environment is dependent on the individual perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use for this technology. Szajna [

53] and Wu and Wang [

54] suggested that TAM needed to integrate with other variables in order to increase the model’s explanatory power.

IDT proposed by Rogers [

55] is used to explain diffusion behavior. New innovation needs to undergo specific communications channels and is accepted by users as time goes on; this is so-called diffusion behavior. Five cognitive constructs of innovation are (1) relative advantage; (2) compatibility; (3) complexity or accessibility; (4) trialability (the degree the users may be tried to use before adoption); and (5) observability. Tornatzky and Klein [

56] researched 57 papers about innovative diffusion and found that only three innovative characteristics had a significant influence on consumers’ decision-making for adopting innovation. Therefore, some research related to innovation adoption only focused on these three variables that influenced adoption behaviors [

57,

58]. The three variables were comparative advantage, compatibility, and accessibility.

Moore and Benbasat [

58] conducted semi-structured interviews with managers whose environments had adopted information technology innovation and obtained 143 valid questionnaires. They used exploratory factor analysis and extracted six factors for mobile payment environment adoption. They were sales growth, cost reduction, flexibility, accessibility, trust and safety, and network externalities. The literature also pointed out that the relative advantage construct included the sub-constructs of sales growth and cost saving. Sheikh et al. [

59] used the questionnaire method from 278 marketing managers to validate the positive impact of relative advantage on the performance of the textile business in Pakistan. The NFC–mobile payment environment would benefit from eliminating to use of cash, offering fast speed and convenience, and exchange of secure data between devices in environments with a high volume of payments, such as restaurants [

21,

29]. Both merchants and consumers benefit from operation time reduction, with feasible cost savings and productivity gains [

29]. According to the survey conducted by Statista [

60], the worldwide mobile payment revenue in 2015 was USD450 billion and is expected to exceed USD1 trillion in 2019, thus becoming one of the most important environments for conducting mobile transactions.

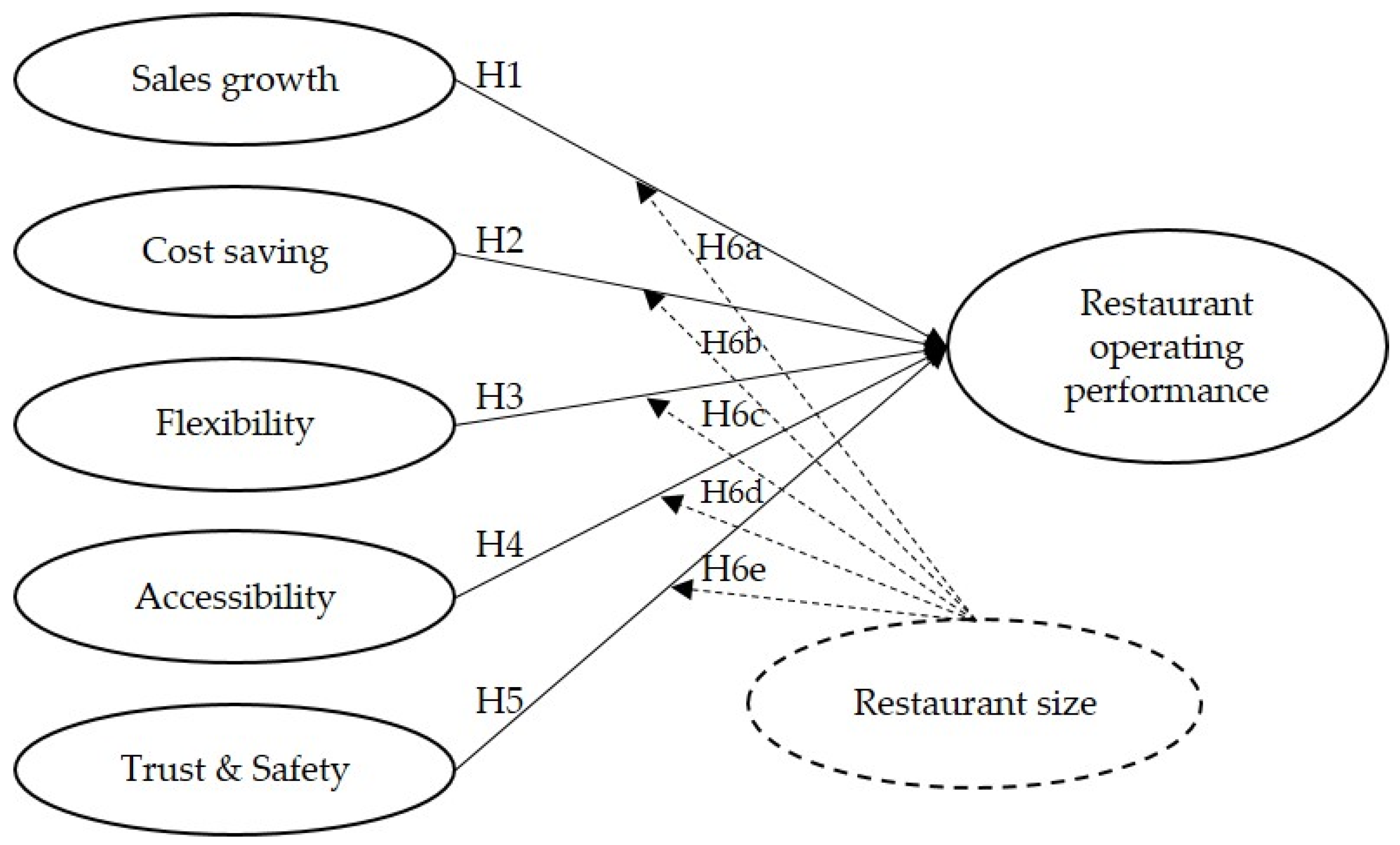

Hence, this paper establishes the following hypothesis:

H1: Relative advantage environment–sales growth has a positive influence on ROP.

H2: Relative advantage environment–cost saving has a positive influence on ROP.

As compared to traditional e-commerce, the most important quality of the mobile payment environment is flexibility. It is the ability to use mobile network functions at any time and any place, providing more services and functions for the users [

61,

62]. Flexibility is also recognized as one of the most important factors for the success of the mobile commerce environment [

63]. Moore and Benbasat [

58] pointed out that the attractive factor for mobile payment users also included flexibility. H3 was established as below:

H3: Flexibility has a positive influence on ROP.

Research has proven that accessibility is a very important aspect in influencing consumers to use new technology [

64,

65]. As the mobile payment environment can provide a greater scope of payment capability, consumers intend to use mobile payment [

49]. Dahlberg et al. [

66] also claimed that accessibility is the most important factor in the mobile payment environment.

H4: Accessibility has a positive influence on ROP.

In spite of the fact that innovation advancements realized numerous advantages for buyers, however, there are still a few factors that could hinder customers’ acknowledgment of the technology innovation. Past literature indicated that new technology often comes with certain risks [

67]. Security is one of the key factors in the acceptance of a new technological environment [

68]. Whether consumers are willing to use the Internet to conduct transactions, primary consideration is given to transaction security [

69], i.e., the more secure the online transaction environment the more the consumer is willing to use online transactions. Chang et al. [

70] suggested that consumers’ and merchants’ payment services rely heavily upon a secure and reliable payment environment, even if it is easy to use. According to research by Bast [

71], restaurants that use NFC mobile payment environments also heavily rely on system security. This paper establishes the following hypothesis:

H5: An environment with trust and safety has a positive influence on ROP.

Melitz and Ottaviano [

72] and Rumelt [

73] revealed that company size is an important moderator for a company’s operational performance, and, as compared to small and medium businesses, large companies have advantages in terms of market, management, and financial resources [

74]. Therefore, according to past literature [

75,

76], this research hypothesizes that the size of the company would have different influences on the relationship between five constructs and ROP as below,

H6a: Company size moderates the relationship between sales growth and ROP.

H6b: Company size moderates the relationship between cost saving and ROP.

H6c: Company size moderates the relationship between flexibility and ROP.

H6d: Company size moderates the relationship between accessibility and ROP.

H6e: Company size moderates the relationship between trust and safety and ROP.