Understanding Revisit Intention towards Religious Attraction of Kartarpur Temple: Moderation Analysis of Religiosity

Abstract

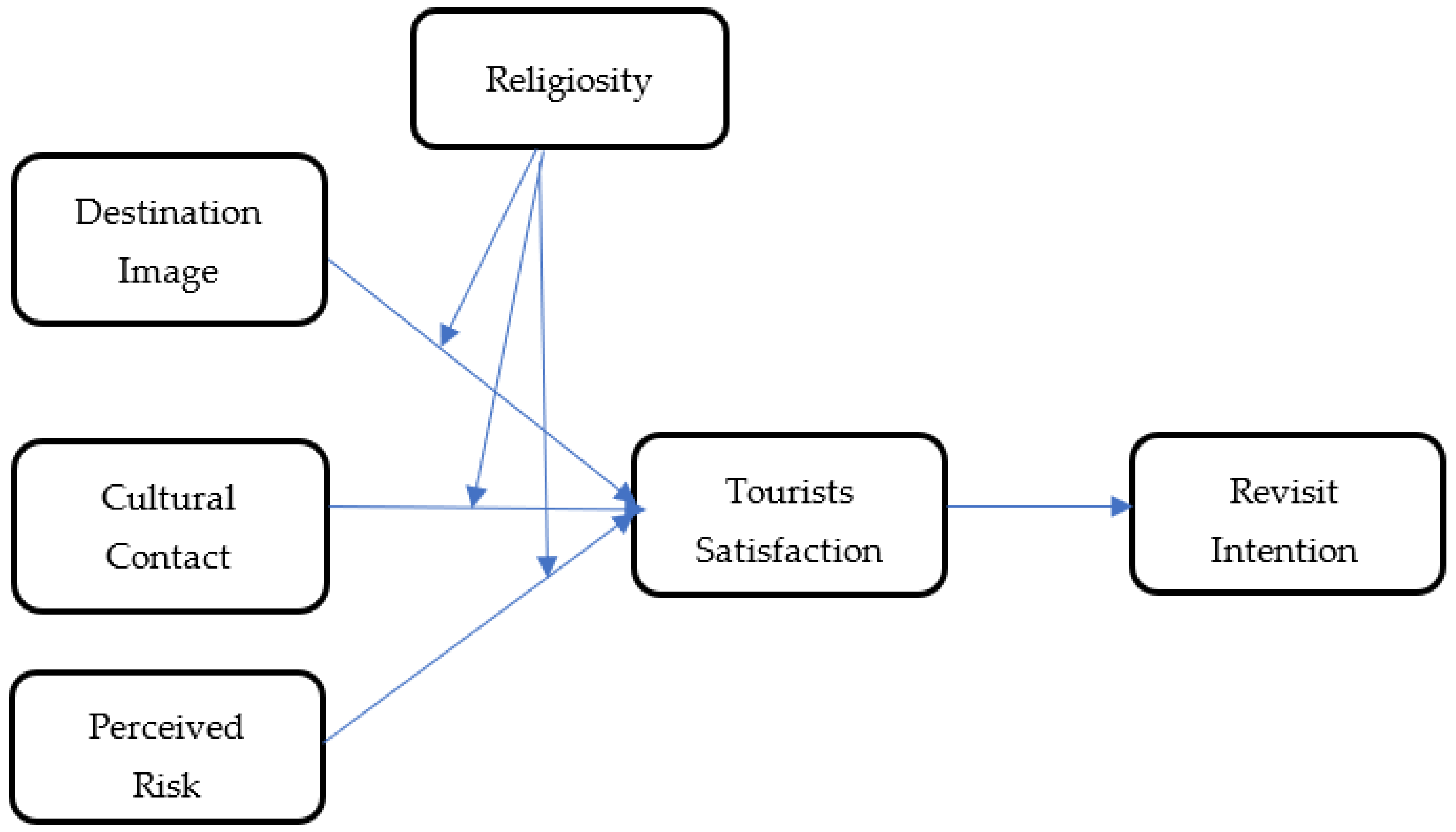

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Destination Image and Tourist Satisfaction

2.2. Cultural Contact and Tourist Satisfaction

2.3. Perceived Risk and Tourist Satisfaction

2.4. Tourist Satisfaction and Revisit Intention

2.5. Mediation of Tourist Satisfaction

2.6. Moderation of Religiosity

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Profile of Respondents

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Common Method Bias-Variance Estimation

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Structural Model of Research

Assessment of Structural Model Fitness

4.4. Hypotheses Testing

4.5. Mediation Effect

4.6. Moderation Effect

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Implications

5.2. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Invest Pakistan. Tourism Sector Profile. Prime Minister’s Office, Board of Investment. 06th Floor, Kohsar Block, Pakistan Secretariat Islamabad, Pakistan: Invest Pakistan. Available online: https://invest.gov.pk/tourism-and-hospitality (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- WTTC. Corona Virus Brief: April 14 2020. 2020. Available online: https://wttc.org/Portals/0/Documents/WTTC%20Coronavirus%20Brief%20External%2014_04.pdf?ver=2020-04-15-081805-253 (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Akhtar, M.S.; Jathol, I.; Hussain, Q.A. Peace Building through Religious Tourism in Pakistan: A Case Study of Kartarpur Corridor. Pak. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2019, 3, 204–212. [Google Scholar]

- Stylidis, D. Exploring resident–Tourist interaction and its impact on tourists’ destination image. J. Travel Res. 2022, 6, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, L.T.I.; So, A.S.I.; Lo, I.S.; Fong, L.H.N. Does the quality of tourist shuttles influence revisit intention through destination image and satisfaction? The case of Macao. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 32, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, H.K.; Lee, T.J.; Yoon, Y.S. Relationship between perceived risk, evaluation, satisfaction, and behavioral intention: A case of local-festival visitors. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoc, K.M.; Trinh, N.T. Factors affecting tourists’ return intention towards vung tau city, Vietnam—A mediation analysis of destination satisfaction. J. Adv. Manag. Sci. 2015, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Park, J.; Kim, M.; Ryu, K. Does perceived restaurant food healthiness matter? Its influence on value, satisfaction and revisit intentions in restaurant operations in South Korea. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, H.; Campon-Cerro, A.M.; Hernandez-Mogollon, J.M. Enhancing rural destinations’ loyalty through relationship quality. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2019, 23, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stylos, N.; Bellou, V.; Andronikidis, A.; Vassiliadis, C.A. Linking the dots among destination images, place attachment, and revisit intentions: A study among British and Russian tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beerli-Palacio, A.; Martín-Santana, J.D. Cultural sensitivity: An antecedent of the image gap of tourist destinations. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2018, 2, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiu, C.M.; Hsu, M.H.; Lai, H.; Chang, C.M. Re-examining the influence of trust on online repeat purchase intention: The moderating role of habit and its antecedents. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 53, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gani, A.A.; Mahdzar, M.; Anuar, N.A.M. Visitor’s experiential attributes and revisit intention to Islamic tourism attractions in Malaysia. J. Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 2019, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- García-Fernandez, J.; Galvez-Ruiz, P.; Fernandez-Gavira, J.; Velez-Colon, L.; Pitts, B.; Bernal García, A. The effects of service convenience and perceived quality on perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty in low-cost fitness centers. Sport Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnoth, J.; Zins, A.H. Developing a tourism cultural contact scale. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.; Zeng, S.; Cheng, P.S.-T. The influence of destination image and tourist satisfaction on tourist loyalty: A case study of Chinese tourists in Korea. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.C. A formative model of the relationship between destination quality, tourist satisfaction and loyalty intention: An empirical test in Vietnam. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 26, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Tasci, A.D. The effect of resident-tourist interaction quality on destination image and loyalty. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1219–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abror, A.; Yunia, W.; Okki, T.; Dina, P. The impact of Halal tourism, customer engagement on satisfaction: Moderating effect of Religiosity. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.M.; Ilkan, M.; Al-Talce, R.; Eluwole, K.K. eWOM, revisit intention, destination trust and gender. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Paramati, S.R. The impact of tourism on income inequality in developing economies: Does Kuznets curve hypothesis exist? Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albaity, M.; Melhem, S.B. Novelty seeking, image, and loyalty—The mediating role of satisfaction and moderating role of length of stay: International tourists’ perspective. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 23, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Goaib, S. Religiosity and social conformity of university students: An analytical study aopustenopplied at King Saud University. Arts J. King Saud Univ. 2003, 16, 51–99. [Google Scholar]

- Aman, J.; Abbas, J.; Mahmood, S.; Nurunnabi, M.; Bano, S. The influence of Islamic Religiosity on the perceived socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development in Pakistan: A structural equation modeling approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- An, S.; Suh, J.; Eck, T. Examining structural relationships among service quality, perceived value, satisfaction and revisit intention for Airbnb guests. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2019, 19, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.A.; Crompton, J.L. Quality, satisfaction and behavioural intentions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K.W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Viet, B.; Dang, H.P. Revisit intention and satisfaction: The role of destination image, perceived risk, and cultural contact. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R. Consumer behavior as risk taking. In Dynamic Marketing for a Changing World; Hancock, R., Ed.; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1960; pp. 389–398. [Google Scholar]

- Bigne, J.E.; Sanchez, M.I.; Sanchez, J. Tourism image, evaluation variables and after purchase behaviour: Inter-relationship. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brătucu, G.; Băltescu, C.; Neacșu, N.; Boșcor, D.; Țierean, O.; Madar, A. Approaching the sustainable development practices in mountain tourism in the Romanian Carpathians. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brug, J.; Aro, A.R.; Oenema, A.; De Zwart, O.; Richardus, J.H.; Bishop, G.D. SARS risk perception, knowledge, precautions, and information sources, the Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M.; Islam, N.U. Impact of perceived risk on tourist satisfaction and future travel intentions: A mediation–moderation analysis. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2021, 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Tsai, D. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F. Investigating structural relationships between service quality, perceived value, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions for air passengers: Evidence from Taiwan. Transp. Res. Part A 2008, 42, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, F.S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Towards green trust: The influences of green perceived quality, green perceived risk, and green satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Phou, S. A closer look at destination: Image, personality, relationship and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.V.; Htaik, S.; Hiele, T.M.; Chen, C. Investigating international tourists’ intention to revisit Myanmar based on need gratification, flow experience and perceived risk. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 18, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.; Gartner, W.C. Destination image and its functional relationships. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martın Gutierrez, H. Estudio de la Imagen de Destino Turıstico y el Proceso Global de Satisfaccion: Adopcion de un Enfoque Integrador. PhD. Thesis, Universidad de Cantabria, Cantabria, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- San Martın Gutierrez, H.; Rodriguez Del Bosque, I. UN enfoque de gesti on de la imagen de marca de los destinos turısticos basado en las caracterısticas Del turista. Rev. Anal. Tur. 2011, 9, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Royo-Vela, M. Rural-cultural excursion conceptualization: A local tourism marketing management model based on tourist destination image measurement. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.W.; Li, X.R.; Pan, B.; Witte, M.; Doherty, S.T. Tracking destination image across the trip experience with smartphone technology. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinillo, S.; Liebana-Cabanillas, F.; Anaya-Sanchez, R.; Buhalis, D. DMO online platforms: Image and intention to visit. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Muskat, B.; Del Chiappa, G. Understanding the relationships between tourists’ emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Rojas, C.; Camarero, C. Visitors’ experience, mood and satisfaction in a heritage context: Evidence from an interpretation center. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, B.; Aksu, A.; Ehtiyar, R.; Cizel, B.; Cizel, R.B.; Icigen, E.T. Relationships among tourist profile, satisfaction and destination loyalty: Examining empirical evidences in Antalya region of Turkey. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 21, 506–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, J. Dynamic nature of destination image and influence of tourist overall satisfaction on image modification. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Odeh, K. The role of tourists’ emotional experiences and satisfaction in understanding behavioral intentions. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylos, N.; Vassiliadis, C.A.; Bellou, V.; Andronikidis, A. Destination images, holistic images and personal normative beliefs: Predictors of intention to revisit a destination. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stylidis, D.; Shani, A.; Belhassen, Y. Testing an integrated destination image model across residents and tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.; Rahman, I. Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovicic, D. Cultural tourism in the context of relations between mass and alternative tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y. Understanding trust and perceived risk in sharing accommodation: An extended elaboration likelihood model and moderated by risk attitude. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2022, 31, 348–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M.M.; Mohd-Any, A.A.; Kamarulzaman, Y. Conceptualizing consumer-based service brand equity (CBSBE) and direct service experience in the airline sector. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 38, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contucci, P.; Ghirlanda, S. Modeling society with statistical mechanics: An application to cultural contact and immigration. Int. J. Methodol. 2007, 41, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, C.Y.; Fang, Y.H. Predicting continuance intention toward mobile branded apps through satisfaction and attachment. Telemat. Inf. 2019, 43, 101248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, O.-C.; Park, J.-W. A Study on the Impact of Cultural Contact Service on Brand Equity. J. Distrib. Sci. 2020, 18, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Tseng, H.-W.; Shiau, Y.-C. Study on the Influence of Cultural Contact and Tourism Memory on the Intention to Revisit: A Case Study of Cultural and Creative Districts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Muñoz-Fernández, G.; Fuentes-García, F.J. Impact of the perceived risk from Covid-19 on intention to travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 970–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, M.F.; Gibson, H.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Thapa, B. The effect of risk perceptions on intentions to travel in the aftermath of September 11, 2001. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 15, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.; Wilson, M.A. The relative risk perception for travel hazards. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapuściński, G.; Richards, B. News framing effects on destination risk perception. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuksel, A.; Yuksel, F. Shopping risk perceptions: Effects on tourists’ emotions, satisfaction and expressed loyalty intentions. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Luo, Q.; Ritchie, B.W. The role of trust in mitigating perceived threat, fear, and travel avoidance after a pandemic outbreak: A multigroup analysis. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Joo, D.; Woosnam, K.M. Sport tourists’ team identification and revisit intention: Looking at the relationship through a nostalgic lens. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 1002–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Choi, Y.; Lee, C.-K.; Ahmad, M.S. Effects of place attachment and image on revisit intention in an ecotourism destination: Using an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanik, J.; Yusuf, M. Effects of perceived value, expectation, visitor management, and visitor satisfaction on revisit intention to Borobudur Temple, Indonesia. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, C.K.; Liu, Y.; Kang, S.; Dai, A. The role of perceived smart tourism technology experience for tourist satisfaction, happiness and revisit intention. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faullant, R.; Matzler, K.; Fuller, J. The impact of satisfaction and image on loyalty: The case of Alpine ski resorts. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2008, 18, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.H.; King, B. An evaluation of satisfaction levels among Chinese tourists in Vietnam. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, M.J.; Jung, T.; Kim, W.G.; Fountoulaki, P. Factors affecting British revisit intention to Crete, Greece: High vs. low spending tourists. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 815–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, G.A.; Kumaravelu, J.; Goh, Y.-N.; Dara Singh, K.S. Understanding the intention to revisit a destination by expanding the theory of planned behaviour (TPB). Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2021, 25, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. Memory, narcissism, and sublimation: Reading Lou Andreas-Salomé’s Freud. J. Am. Imago 2000, 57, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B. Cultural centre, destination cultural offer and visitor satisfaction. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romao, J.; Neuts, B.; Nijkamp, P.; van Leeuwen, E. Culture, product differentiation and market segmentation: A structural analysis of the motivation and satisfaction of tourists in Amsterdam. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, N.T.; Dung, H.T.; Dat, N.V.; Duc, P.M.; Hung, N.T.; Phuong, N.T.T. Cultural contact and service quality components impact on tourist satisfaction. J. Southwest Jiao Tong Univ. 2020, 55, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, V.W.S.; Ritchie, J.B. Exploring the essence of memorable tourism experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1367–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, L. Factors in risk perception. Risk Anal. 2000, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Crotts, J.C.; Law, R. The impact of the perception of risk on international travelers. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 9, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindrasih, E. Tourist’s perceived risk and image of the destinations prone to natural disasters: The case of Bali and Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Humaniora 2018, 30, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, M.S.; Alfandi, A.M. Determining behaviour intentions from the overall destination image and risk perception. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 25, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, E.Y.T.; Jahari, S.A. Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post-disaster Japan. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Q.; Bulte, E.; Tan, S. Religiosity and economic performance: Micro-econometric evidence from Tibetan area. China Econ. Rev. 2011, 22, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johan, Z.J.; Putit, L. Conceptualizing the influences of knowledge and religiosity on islamic credit compliance. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdcroft, B.B. What is religiosity? Cathol. Educ. A J. Inq. Pract. 2006, 10, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joseph, S.; DiDuca, D. The Dimensions of Religiosity Scale: 20-item self-report measure of religious preoccupation, guidance, conviction, and emotional involvement. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2007, 6, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemo, D.A.; Adeleye, A.T. Emotional intelligence, religiosity and self-efficacy as predictors of psychological well-being among secondary school adolescents in Ogbomoso, Nigeria. Eur. J. Psychol. 2008, 4, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, R.; El-Gohary, H. The role of islamic religiosity on the relationship between perceive value and tourist satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitell, S.J.; Bing, M.N.; Davison, H.K.; Ammeter, A.; Garner, B.L.; Novicevic, M. Religiosity and moral identity: The mediating role of self-control. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeganeh, H. Religiosity, socio-economic development and work values: A cross-national study. J. Manag. Dev. 2015, 34, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani-Farahani, H.; Musa, G. The relationship between Islamic Religiosity and residents’ perceptions of socio-cultural impacts of tourism in Iran: Case studies of Sare’in and Masooleh. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 802–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eutsler, J.; Lang, B. Rating scales in accounting research: The impact of scale points and labels. Behav. Res. Account. 2015, 27, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Chelliah, S.; Ahmed, S. Factors influencing destination image and visit intention among young women travelers: Role of travel motivation, perceived risks, and travel constraints. Asia Pac. J. Tourism Res. 2017, 22, 1139–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Hsieh, C.M.; Lee, C.K. Examining Chinese college students’ intention to travel to Japan using the extended theory of planned behavior: Testing destination image and the mediating role of travel constraints. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrey, S.H.; Hakim, I.A.; Rather, R.A. Mediating role of government initiatives and media influence between perceive risks and destination image: A study of conflict zone. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2018, 5, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.C.; Dam, D.X. Factors affecting European tourists’ satisfaction in Nha Trang City: Perceptions of destination quality. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2017, 3, 350–362. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, L.C. Perceived risk and destination knowledge in the satisfaction-loyalty intention relationship: An empirical study of European tourists in Vietnam. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 33, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variable and measurement error. J. Mark. Research. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electr. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 4, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, J.B. Core reporting practices in structural equation modeling. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 2008, 4, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM indeed a silver Bullet. J. Market. Theory Practice. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling: A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Hong, S. Power analysis in covariance structure modeling using GFI AGFI. Multivar. Behavior. Res. 1997, 32, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.X.; Jin, M.; Shi, W. Tourism as an important impetus to promoting economic growth: A critical review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.K.; Ismail, A.R.; Islam, M.D.F. Tourist risk perceptions and revisit intention: A critical review of literature. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2017, 4, 1412874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayode-Adedeji, T.; Nwakerendu, I. The Dissemination of fake news on social media: A demographic analysis of audience involvement. In Proceedings of the 9th European Conference on Social Media, Krakow, Poland, 12–13 May 2022; Volume 9, pp. 289–297. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 389 | 63% |

| Female | 224 | 37% |

| Age | ||

| Under 22 years | 107 | 17.5% |

| 22 to 35 years | 177 | 28.8% |

| 3 to 60 years | 189 | 30.8% |

| Above 60 years | 140 | 22.9% |

| Education | ||

| Primary | 177 | 28.9% |

| Secondary | 279 | 45.5% |

| College/University | 138 | 22.5% |

| Professional Status | ||

| Full-time employed | 147 | 23.9% |

| Part-time employed | 88 | 14.4% |

| Students | 108 | 17.6% |

| Businessman | 142 | 23.1% |

| Retired | 128 | 21% |

| Nationality | ||

| Indian | 452 | 73.7% |

| International | 161 | 26.3% |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 477 | 77.8% |

| Single | 136 | 22.2% |

| Construct | Indicators | SFL | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Contact | Attracted to local traditional culture at “Kartarpur” temple | 0.95 | 0.693 | 0.898 |

| I give more attention to the local traditional culture here at “Kartarpur” temple religious activates | 0.84 | |||

| I like the local traditional culture at “Kartarpur” Temple | 0.61 | |||

| I understand the connotation of traditional culture at “Kartarpur” Temple. | 0.89 | |||

| Destination Image | Kartarpur temple has a quality tourism infrastructure | 0.78 | 0.660 | 0.955 |

| Kartarpur temple has a good climate | 0.73 | |||

| Kartarpur temple is safe and stable | 0.79 | |||

| Kartarpur temple has a good quality of life | 0.88 | |||

| Kartarpur temple has appealing local cuisine | 0.81 | |||

| Kartarpur temple has a variety of unique attractions | 0.85 | |||

| Kartarpur temple is rich in cultural heritage | 0.86 | |||

| Kartarpur is a good place for shopping | 0.86 | |||

| Kartarpur people are interesting and friendly | 0.63 | |||

| Kartarpur is a pleasant place to visit | 0.89 | |||

| Kartarpur has several springs | 0.82 | |||

| Perceived Risk | Overall the experience to visit the “Kartarpur” temple will not be a good value of money | 0.76 | 0.693 | 0.947 |

| Threat of becoming sick while traveling or at “Kartarpur” temple. | 0.82 | |||

| Psychological trauma because of others’ negative comments about the facilities at “Kartarpur” temple. | 0.77 | |||

| You feel there is a chance of physical danger to my health during the “Kartarpur” temple visit. | 0.87 | |||

| You feel that you might get caught up in political turmoil during the “Kartarpur” temple visit. | 0.84 | |||

| You perceive language barriers during the “Kartarpur” temple. | 0.82 | |||

| You perceive the risk of a terrorist attack during the “Kartarpur” temple visit. | 0.92 | |||

| You will not receive enough personal satisfaction during the “Kartarpur” temple. | 0.85 | |||

| Tourist Satisfaction | I enjoyed the visit to the “Kartarpur” temple. | 0.75 | 0.586 | 0.918 |

| I am a person who identifies strongly with my profession | 0.82 | |||

| I prefer this destination, the “Kartarpur” temple. | 0.89 | |||

| I have positive feelings regarding the “Kartarpur” temple. | 0.79 | |||

| This experience is exactly what I needed. | 0.78 | |||

| This was spiritual to visit the “Kartarpur” temple. | 0.73 | |||

| This visit was better than expected “Kartarpur” temple. | 0.66 | |||

| My choice to make this trip was the wise “Kartarpur” temple. | 0.68 | |||

| Revisit Intention | Intend to revisit “Kartarpur” temple, Pakistan | 0.82 | 0.712 | 0.881 |

| Intend to recommend “Kartarpur” temple, Pakistan to others | 0.89 | |||

| Plan to revisit “Kartarpur” temple, Pakistan. | 0.82 | |||

| Religiosity | Religious Beliefs | 0.84 | 0.694 | 0.901 |

| Religious Practices | 0.82 | |||

| Religious community attachments | 0.88 | |||

| Religious Value | 0.79 |

| Construct | Mean | SD | VIF | Cultural Contact | Destination Image | Perceived Risk | Tourist Satisfaction | Revisit Intention | Religiosity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Contact | 5.302 | 1.281 | 1.321 | 0.83 | |||||

| Destination Image | 5.278 | 1.318 | 1.436 | 0.31 | 0.81 | ||||

| Perceived Risk | 4.499 | 1.133 | 1.233 | −0.33 | −0.44 | 0.83 | |||

| Tourist Satisfaction | 4.783 | 1.534 | 1.421 | 0.49 | 0.39 | −0.42 | 0.76 | ||

| Revisit Intention | 5.146 | 1.238 | 1.237 | 0.38 | 0.17 | −0.19 | 0.37 | 0.84 | |

| Religiosity | 5.129 | 1.231 | 1.115 | 0.42 | 0.29 | −0.33 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.83 |

| Path | Standardized Estimation | t-Statistics | p-Value | Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Destination Image → Tourists Satisfaction | 0.491 | 8.422 | <0.001 | Supported |

| Cultural contact → Tourists Satisfaction | 0.482 | 7.810 | <0.001 | Supported |

| Perceived Risk → Tourists Satisfaction | −0.376 | −6.559 | <0.001 | Supported |

| Tourists Satisfaction → Revisit Intention | 0.398 | 4.226 | <0.001 | Supported |

| Structural Model | Cut-off Value | |||

| Model fit statistics | Chi-square = 566.458 d.f. = 198 p-value = 0.000 | |||

| Absolute fit index | Normed Chi-Square = 2.799 RMSEA = 0.052 GFI = 0.924 AGFI = 0.842 | −3.0 <0.08; good fit >0.90 >0.80 | ||

| Incremental fit index | NFI = 0.956 IFI = 0.952 CFI = 0.961 TLI = 0.957 RFI = 0.962 | >0.90 >0.90 >0.90 >0.90 RFI Close to 1; good fit | ||

| Parsimonious fit index | PCFI = 0.786 PNFI = 0.789 PGFI = 0.712 | >0.50 >0.50 >0.50 | ||

| Hypothesis | Standard Coefficient | t-Statistics | Standard Error | p-Value | Support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H8 | Destination image → Tourist’s satisfaction Religiosity → Tourist’s satisfaction Destination image x Religiosity → Tourist’s satisfaction | 0.376 ** 0.484 *** 0.970 *** | 6.578 7.823 8.334 | 0.054 0.067 0.027 | 0.000 0.000 0.000 | Yes |

| H9 | Cultural contact → Tourist’s satisfaction Religiosity → Tourist’s satisfaction Cultural contact x Religiosity → Tourist’s satisfaction | 0.318 ** 0.512 *** 0.432 * | 4.329 4.439 7.981 | 0.109 0.132 0.029 | 0.000 0.000 0.004 | Yes |

| H10 | Perceived Risk → Tourist’s satisfaction Religiosity → Tourist’s satisfaction Perceived risk x Religiosity → Tourist’s satisfaction | −0.389 ** 0.469 ** −0.329 * | −4.112 5.783 −4.439 | 0.056 0.057 0.027 | 0.002 0.000 0.000 | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rehman, A.U.; Shoaib, M.; Javed, M.; Abbas, Z.; Nawal, A.; Zámečník, R. Understanding Revisit Intention towards Religious Attraction of Kartarpur Temple: Moderation Analysis of Religiosity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148646

Rehman AU, Shoaib M, Javed M, Abbas Z, Nawal A, Zámečník R. Understanding Revisit Intention towards Religious Attraction of Kartarpur Temple: Moderation Analysis of Religiosity. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148646

Chicago/Turabian StyleRehman, Asad Ur, Muhammad Shoaib, Mohsin Javed, Zuhair Abbas, Ayesha Nawal, and Roman Zámečník. 2022. "Understanding Revisit Intention towards Religious Attraction of Kartarpur Temple: Moderation Analysis of Religiosity" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148646

APA StyleRehman, A. U., Shoaib, M., Javed, M., Abbas, Z., Nawal, A., & Zámečník, R. (2022). Understanding Revisit Intention towards Religious Attraction of Kartarpur Temple: Moderation Analysis of Religiosity. Sustainability, 14(14), 8646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148646