Understanding the Relational Dynamics of Chilean Rural Teachers: Contributions from a Narrative-Generative Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Generativity and Pedagogy as a Key Element in Rural Schools

2.2. Rural Schools and Their Affectivity in the Management of SDG 4: Collaboration with Educational Quality in Chile

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Data Collection Techniques

3.4. Data Analysis and Production Strategy

4. Results

“… I find myself a person who reaches out easily to people, that I am always respectful of others… also reaching out to children, I have always liked listening to them, listening to them, always respecting their opinion, having a way of reaching out to them…”(Rural Educator, MV—IX Region of La Araucanía).>

“… you have to put yourself in the child’s place in order to be able to teach, because otherwise the child is not going to learn… in the rural area, as this subject is so small, it is so personalised, you know the children even when they arrive angry and they don’t teach you that at university… you learn that on a day-to-day basis with the students, so I feel that practice teaches you a lot, a lot… to be empathetic, if someone is going through a difficult moment, there are so many ways to accompany and support the students…”(Rural Educator, CY—XIV Region of Los Ríos).

“… I believe that a rural educator has to have the capacity to adapt to all learning rhythms, to all the particular situations of each child, to the context, to their socio-emotional conditions… to their intellectual capacities…”(Rural educator, CO—IX Region of La Araucanía).

“… we stayed, and my husband was very important, because he helped me in everything, if I told him, you know what? I need this at school, because I need this structure… he was going to do it there… the children were happy, when we did a degree…”(Rural educator, CY—XIV Region Los Ríos).

“… look, my daughter who grew up with me in my work, she has been very understanding, because she shares her affection with my students, of course, she is not like other children who become envious, who start asking for more time, no, she is quite the opposite, every time she has been able to help me, she helps me… I have been blessed that I was able to raise my daughter working with me and I do not know if there is another person who can say the same…”(Rural Educator, SJ—RM).

“… Happily married with a situation of tranquility, already seeing achievements, in relation to the family part as well, why not say it, as a professional… I try to communicate more with my children… through sport we have always been very close… I have tried to be a good father… we try to be always sharing…”(Rural Educator, PI—XIV Los Ríos).

“… we have a trilogy, between education, parents, and the municipality, in order to move the school forward… everyone collaborates in equal parts so that the children have a better service… the school is very open towards the community… all activities are done together with the community…”(Rural Educator, CO—IX Region of La Araucanía).

“… I am a person who likes to interact socially with colleagues, with peers, or also sometimes when they are people from different professional fields… in the microcentre meetings, there is a whole programme, there is a whole programme of continuous improvement for rural colleagues… for me human relations are very important, first that there is a group with good communication, with good human, interpersonal relations, to be able to work, because we cannot work if there are differences of ideas or differences of criteria…”(Rural Educator, MC—IX Region of La Araucanía).

“… I don’t have problems with anyone, being a mother, being a mother and at the same time being a teacher… I think this is a strength for me, so there is a lot of confidence, especially with the girls, I do have the ability to persuade the children… to accompany them and contain them… it has been very useful for me…”.(Rural Educator, P2—RM).

“… I have always wanted to get to know the community before anything else, that is, to get to know the people, visit their homes, talk to them, talk to the parents, what they want, what they expect from their children… what their needs are, what they expect from us as teachers… the work must be collaborative…”(Rural Educator, MV—IX Region of La Araucanía).

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Projections of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sandoval-Obando, E. La Profesionalidad Docente Rural: Implicaciones Socioeducativas Desde la Perspectiva Narrativa Generativa; Documento sin Publicar, FONDECYT de Iniciación Nº 11190028; FONDECYT: Temuco, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, J.I.; Leite, A.E.; Cortés, P.; Márquez, M.J.; Padua, D. La configuración de identidades en la experiencia escolar. Escenarios, sujetos y regulaciones. Rev. Educ. 2010, 353, 187–209. Available online: http://www.revistaeducacion.educacion.es/re353/re353_07.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Balbontin, R.; Rojas, N. Percepciones sobre la identidad del profesor rural en la Región del Ñuble, Chile. Rev. Educ. Am. 2020, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarauta, B.; Pérez, M.J. La construcción de la identidad profesional del maestro de primaria durante su formación inicial. El caso de la Universidad de Barcelona. Profr. Rev. Curríc. Form. Profr. 2017, 21, 103–122. Available online: https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/profesorado/article/view/58053 (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Vera, D.; Osses, S.; Schiefelbein, E. Las Creencias de los profesores rurales: Una tarea pendiente para la investigación educativa. Estud. Pedagóg. 2012, 38, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawaz, M.; Rojas, P. En busca de una educación rural más pertinente. Una experiencia en las escuelas básicas de la provincia de Ñuble. Horiz. Educ. 2004, 25–36. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/979/97917171004.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Castro, A. Familias rurales y sus procesos de transformación: Estudio de casos en un escenario de ruralidad en tensión. Psicoperspectivas 2012, 11, 180–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyarzún, J.D.D. Tensions between education and development in rural territories in Chile: Neglected places, absent policies. In Handbook on Promoting Social Justice in Education; Papa, E.R., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 283–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, J. Resultados de Aprendizaje en América Latina a Partir de las Evaluaciones Nacionales. UNESCO/OREALC. 2007. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0015/001555/155567s.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Hargreaves, L. Respect and Responsability: Review of Research on small Rural Schools in England. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2009, 48, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchoarena, D.; Gasperini, L. Educación Para el Desarrollo Rural: Hacia Nuevas Respuestas de Política; FAO/UNESCO: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- SIMCE. Resultados Nacionales SIMCE 2017. Ministerio de Educación. 2017. Available online: http://www.revistadeeducacion.cl/resultados-simce-2017-pocos-avances-y-grandes-desafios-en-educacion-media/ (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Vera, D.; Salvo, S.; Zunino, H. En Torno al Cierre de las Escuelas Rurales en Chile. Antecedentes para la implementación de una Política de Estado. Investig. Educ. 2013, 13, 123–143. Available online: http://revistas.ufro.cl/index.php/educacion/article/view/1066 (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Ávalos, B. Desarrollo Docente en el Contexto de la Institución Escolar: Los Microcentros Rurales y los Grupos Profesionales de Trabajo en Chile; MINEDUC: Santiago, Chile, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cárcamo, H. Microcentros de escuelas rurales de la provincia de Ñuble, Chile: Representaciones que posee el profesorado respecto de su impacto en el quehacer pedagógico en el escenario de la nueva ruralidad. Sinéctica 2016, 1–17. Available online: https://sinectica.iteso.mx/index.php/SINECTICA/article/view/639 (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Castillo-Miranda, S.; Castro, G.; Hidalgo-Standen, C. La evaluación del desempeño docente desde la perspectiva de profesores de educación rural. Educ. Educ. 2017, 20, 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo, M.; Rebolledo, J.; Besoaín-Saldaña, A. Monitoring inclusive education in Chile: Differences between urban and rural areas. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2017, 53, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, C.; González, B.; Ascorra, P.; Grech, S. Contar para Comprender: Cierre de Escuelas Rurales Municipales en Chile y sus Implicancias para las Comunidades. Educ. Soc. 2020, 41, e215922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, C.; Peña, M.; Cubillos, F.; Solorza, H. Estamos todos juntos: El cierre de la Escuela Rural desde la perspectiva de los niños. Educ. Pesqui. 2016, 42, 953–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacarés, J.; Serra, E. Explorando el territorio del desarrollo adulto: La clave de la generatividad. Cult. Educ. 2011, 23, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, F.; Serrat, R.; Pratt, M. Older age as a time to contribute: A scoping review of generativity in later life. Ageing Soc. 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, F.; López, O.; Celdrán, M. La generatividad en la vejez y su relación con el bienestar:¿ Quién más contribuye es quien más se beneficia? An. Psicol. 2013, 29, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Arellano, O.; García-Méndez, M.; Garduño-Espinosa, J.; Vargas-Guadarrama, L.; Mendoza-Núñez, V. Reliability of a Scale for the Evaluation of Generativity Relative to Health (GeReH) in the Mexican Population in the Aging Process. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, I. Factores Motivacionales y Evolutivos que Influyen en la Elección de la Carrera Docente en Educación Inicial. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain, 2019. Available online: https://renati.sunedu.gob.pe/bitstream/sunedu/2137098/1/RomeroGonzalesIP.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Larraín, M.; Zegers, B.; Orellana, Y. Generativity and Life Satisfaction in a sample of grandparents from Santiago, Chile. Ter. Psicol. 2019, 37, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Obando, E.; Altamirano, V.; Isla, B.; Loyola, V.; Painecura, C. Social and Political Participation of Chilean Older People: An Exploratory Study from the Narrative-Generative Perspective. Arch. Health 2021, 2, 1631–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercoli Palavecino, K.; Sandoval-Obando, E. Implicaciones del Envejecimiento Potencialmente Generativo en Personas Mayores Chilenas: Una Exploración Inicial. Braz. J. Dev. 2021, 7, 105006–105029. Available online: https://www.brazilianjournals.com/index.php/BRJD/article/view/39556 (accessed on 17 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Herrera, M.; Galkuté, M.; Fernández, M.; Elgueta, R. Grandparent-grandchild relationships, generativity, subjective well-being and self-rated health of older people in Chile. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 296, 114786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Dimensions of a New Identity; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kotre, J. Outliving the Self: Generativity and the Interpretation of Lives; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, C. Generativity-Stagnation: Development of a status model. Dev. Rev. 1997, 17, 252–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C.L.; Marcia, J.E. Generativity-Stagnation: A Five-Category Model. J. Personal. 1998, 66, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, R.; Girling, L.; De Medeiros, K.; Brazda, M.; Hannum, S. Extending the Framework of Generativity Theory through Research: A Qualitative Study. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Romero, D.; Fernández, I.; Tomás, J.; Cerviño-Vázquez, C.; Georgieva, S. Factorial Validity of a Spanish Language Generativity Scale: Yet Another Scale with Method Effects? Pensando Psicol. 2017, 13, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P.; de St. Aubin, E. A theory of generativity and its assessment through self-report, behavior acts, and narrative themes in autobiography. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 62, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D. Generativity in midlife. In Handbook of Midlife Development; Lachman, E.M.E., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 395–443. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2001-06209-009 (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Arias, A.; Iglesias, S. La Generatividad como una Forma de Envejecimiento Exitoso. Estudio del efecto Mediacional de los Vínculos Sociales. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2015, 5, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sandoval-Obando, E. La Profesionalidad Docente Rural Chilena desde la Perspectiva Narrativa Generativa: Una Exploración Inicial. In Libro de Investigación. V. RIDGE: Liderazgo y Gestión Educativa Para un Mundo Mejor; Arboleda, J., Ed.; Red Iberoamericana de Pedagogía/Universidad Católica del Maule: Maule, Chile, 2020; pp. 132–152. Available online: https://redipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Libro-ridge-2020.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Ramírez, M.; de la Herrán, A. La madurez personal en el desarrollo profesional del docente. REICE Rev. Electrón. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2012, 10, 25–44. Available online: https://revistas.uam.es/index.php/reice/article/view/3039 (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Vaillant, G. Aging Well: Surprising Guideposts to a Happier Life from the Landmark Study of Adult Development; Hachette Book Group: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval-Obando, E. Caracterizando la Identidad Narrativa en Educadores Rurales Chilenos: Una Propuesta de Investigación. In Nuevas Miradas en Psicología del Ciclo Vital; Sandoval-Obando, E., Serra Desfilis, E., García, Ó., Eds.; RIL Editores/Universidad Autónoma de Chile: Providencia, Chile, 2020; pp. 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, J.; Busch, H.; Au, A.; Poláčková Šolcová, I.; Tavel, P.; Tsien Wong, T. For the benefit of others: Generativity and meaning in life in the elderly in four cultures. Psychol. Aging 2014, 29, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, J. Intergenerational programs and the promotion of generativity. J. Intergener. Relatsh. 2014, 12, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, J.J.; Uribe, D. Mercados Universitarios: El Nuevo Escenario de la Educación Superior; Ediciones Universidad Diego Portales: Santiago, Chile, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, D.; Renes, S. Fairness views and political preferences: Evidence from a large and heterogeneous sample. Soc. Choice Welf. 2021, 56, 679–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiligiris, V.; Hill, C. A prospective model for aligning educational quality and student experience in international higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2021, 46, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Zamar, M.-D.; Abad-Segura, E.; López-Meneses, E.; Gómez-Galán, J. Managing ICT for Sustainable Education: Research Analysis in the Context of Higher Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Bucarey, C.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Müller-Pérez, S.; Aguilar-Gallardo, L.; Mora-Moscoso, M.; Vargas, E.C. Student’s Satisfaction of the Quality of Online Learning in Higher Education: An Empirical Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, J.; Duk, C. SDG 4 (and 16) as a goal for the next years. Rev. Latinoam. Educ. Inclusiva 2017, 11, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Triviño-Amigo, N.; Barrios-Fernandez, S.; Mañanas-Iglesias, C.; Carlos-Vivas, J.; Mendoza-Muñoz, M.; Adsuar, J.C.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Rojo-Ramos, J. Spanish Teachers’ Perceptions of Their Preparation for Inclusive Education: The Relationship between Age and Years of Teaching Experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, J.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Müller, S.; Kalia, P.; Mehmood, K. Predictive Sustainability Model Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior Incorporating Ecological Conscience and Moral Obligation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Muñoz, M.; Rodal, M.; García-Gordillo, M.Á.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; García-Matador, J.; Calzada-Rodríguez, J.I.; Morenas-Martín, J. Spanish Translation and Cultural Adaptation of the Fibromyalgia Knowledge Questionnaire. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triviño-Amigo, N.; Barrios-Fernandez, S.; Mañanas-Iglesias, C.; Carlos-Vivas, J.; Adsuar, J.C.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Rojo-Ramos, J. Differences among Male and Female Spanish Teachers on Their Self-Perceived Preparation for Inclusive Education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, Á.E.; Vergara, O.; Fernández, I.; González, Y. La triple concordancia didáctica como proceso de gestión para el desarrollo estratégico de la responsabilidad social universitaria desde el enfoque por resultados de aprendizajes. Sapienza Organ. 2018, 5, 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Argüello, A.; Pineda, B.; Turcios, P. Competencias del docente en educación online en tiempo de COVID-19: Universidades Publicas de Honduras. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2020, 26, 206–224. [Google Scholar]

- Cóbano-Delgado, V.; Llorent-Bedmar, V. Bienestar de las mujeres y desarrollo rural en la España despoblada. J. Medio Ambiente Res. Salud Pública 2020, 17, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos Oradini, N.; Araya Castillo, L.; Duque, Á.A.; Yáñez Jara, V.; Gambra Acle, X.; Cornejo Orellana, C. Gratuidad de la Educación Superior en Chile. Arandu-UTIC. Rev. Cient. Int. Univ. Tecnol. Intercont. 2020, 7, 163–188. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, D.; Steiner, A.; Mazzei, M.; Baker, R. Filling a void? The role of social Enterprise in addressing social isolation and loneliness in rural communities. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaiz Sánchez, P.; De Haro-Rodríguez, R.; Maldonado Martínez, R.M. Barriers to Student Learning and Participation in an Inclusive School as Perceived by Future Education Professionals. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2019, 8, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Kaur, M. Mediating educational challenges amidst COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pac. J. Contemp. Educ. Commun. Technol. 2020, 6, 40–57. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt-Odio, M.A.; Sartor-Harada, A.; Ulloa-Guerra, O.; Azevedo-Gomes, J. Self-Perceptions on Digital Competences for M-Learning and Education Sustainability: A Study with Teachers from Different Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteve-Faubel, R.P.; Oller-Benitez, A.; Aparicio-Flores, M.P. Perceptions of Future Teachers of Audiovisual Education and Communication. Challenges in Training for a Sustainable Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albornoz, M.E. ¿Calidad Educativa Significa lo Mimos Para Todos los Actores Escolares? Recuperado 2005. Available online: http://mayeuticaeducativa.idoneos.com/index.php/347332 (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Feu Gelis, J.; Torrent Font, A. El tipo ideal de escuela innovadora que promueve la sostenibilidad: El caso de las comunidades rurales de Cataluña. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morén, R. Lugar, Identidad Territorial e Inmigración Extranjera en Áreas Rurales y Pequeñas Ciudades de España. Un Estudio Cualitativo Exploratorio; Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales (MTAS): Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Millán Escriche, M. La diversificación en el medio rural como factor de desarrollo. Pap. Geogr. 2002, 36, 223–238. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/geografia/article/view/46561 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Otzen, T.; Manterola, C. Técnicas de Muestreo sobre una Población a Estudio. Int. J. Morphol. 2017, 35, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S. Las Entrevistas en Investigación Cualitativa; Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Diaz, R.; Acevedo Duque, Á.; Martin Fiorino, V.; Cachicatari Vargas, E. Cultura investigativa del docente en Latinoamérica en la era digital. Comun. Rev. Cient. Iberoam. Comun. Educ. 2022, 30, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.; McLean, K. Narrative identity. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Obando, E. La profesionalidad docente rural chilena: Implicaciones socioeducativas de un desarrollo generativo trascendente. Prax. Pedagóg. 2021, 21, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, E. Somos lo que contamos: La Historia de Vida como método evolutivo. In La Fotobiografía: Imágenes e Historias del Pasado Para Vivir con Plenitud el Presente; Sanz, F., Ed.; Kairós: Barcelona, Spain, 2008; pp. 405–415. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D. Tracing Three Lines of Personality Development. Res. Hum. Dev. 2015, 12, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.; Olson, B. Personality Development: Continuity and Change Over the Life Course. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 517–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAdams, D.P.; Logan, R. What is generativity? In The Generative Society: Caring for Future Generations; de St. Aubin, E., McAdams, D.P., Kim, T.-C., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D.P.; Hart, H.M.; Maruna, S. The anatomy of generativity. In Generativity and Adult Development: How and Why We Care for the Next Generation; McAdams, D.P., de St. Aubin, E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 7–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D. The Life Story Interview; The Foley Center for the Study of Lives/Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 2008; Available online: https://www.sesp.northwestern.edu/foley/instruments/interview/ (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Bases de la Investigación Cualitativa. Técnicas y Procedimientos para Desarrollar la Teoría Fundamentada; Universidad de Antioquia: Medellín, Colombia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Trigueros, C.; Rivera-García, E.; Rivera-Trigueros, I. Técnicas Conversacionales y Narrativas. Investigación Cualitativa con Software Nvivo; Universidad de Granada/Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública: Granada, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, C.; Lorenzo, O.; Herrera, L. Teoría y Práctica del Análisis de Datos Cualitativos. Proceso General y Criterios de Calidad. Rev. Int. Cienc. Soc. Humanid. 2005, 15, 133–154. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, M. La Investigación Cualitativa Etnográfica en Educación. Manual Teórico Práctico; Trillas: Bogota, Colombia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval-Obando, E.; Zacarés, J. Generatividad y Desarrollo Adulto. In Nuevas Miradas en Psicología del Ciclo Vital; Sandoval-Obando, E., Serra Desfilis, E., García, Ó., Eds.; RIL Editores/Universidad Autónoma de Chile: Providencia, Chile, 2020; pp. 189–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Obando, E. Implicancias Socioeducativas de la Generatividad en Educadores Rurales Chilenos. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 2, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Obando, E. Generatividad y Desarrollo Socioemocional en el Profesorado: Desafíos e Implicancias Educativas Actuales. In Desarrollo Humano y Educación Socioemocional; Arboleda, J., Ed.; Red Iberoamericana de Pedagogía: Maule, Chile, 2021; pp. 23–51. [Google Scholar]

- Gáspár, T.; Laurén, L.M. Future generations: Widespread changes in our living-together. Futures 2013, 45, S1–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.W.; Norris, J.E.; Arnold, M.L.; Filyer, R. Generativity and moral development as predictors of value-socialization narratives for young persons across the adult life span: From lessons learned to stories shared. Psychol. Aging 1999, 14, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.W.; Danso, H.A.; Arnold, M.L.; Norris, J.E.; Filyer, R. Adult generativity and the socialization of adolescents: Relations to mothers’ and fathers’ parenting beliefs, styles, and practices. J. Personal. 2001, 69, 89–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.; Arnold, J. The nature, prevalence and correlates of generativity among men in middle career. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urien, B.; Kilbourne, W. Generativity and self-enhancement valuesin eco-friendly behavioral intentions and environmentally responsible consumption behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chee, K.; Gerhart, O. Redefining generativity: Through life course and pragmatist lenses. Sociol. Compass 2017, 11, e12533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska, L. Subjectivity and generativity in midlife. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 48, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDermid, S.; Franz, C.; DeReus, L. Adult character: Agency, communion, insight, and the expression of generativity in midlife adults. In Competence and Character through Life; Colby, A., James, J., Hart, D., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1998; pp. 205–229. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, M.W.; Lawford, H.L.; Matsuba, M.K.; Villar, F. The life span development of generativity. In The Oxford Handbook of Moral Development: An Interdisciplinary Perspective; Jensen, A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 366–384. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, H.M.; McAdams, D.P.; Hirsch, B.J.; Bauer, J.J. Generativity and social involvement among African Americans and White adults. J. Res. Personal. 2001, 35, 208–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Childhood and Society; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A.S. Developmental roots of adult social responsibility. In Caring and Doing for Others: Social Responsibility in the Domains of Family, Work, and Community; Rossi, A.S., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2001; pp. 227–320. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A.S. Domains and dimensions of social responsibility: A sociodemographic profile. In Caring and Doing for Others: Social Responsibility in the Domains of Family, Work, and Community; Rossi, A.S., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2001; pp. 97–134. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, B.E.; Stewart, A.J. Generativity and social motives in young adults. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frensch, K.M.; Pratt, M.W.; Norris, J.E. Foundations of generativity: Personal and family correlates of emerging adults’ generative life-story themes. J. Res. Personal. 2007, 41, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, A.F. Toward a theory of generative change in culturally and linguistically complex classrooms. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2009, 46, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Ball, A.F. Critical reflection and generativity: Toward a framework of transformative teacher education for diverse learners. Rev. Res. Educ. 2019, 43, 68–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K. Critical reflection as a framework for transformative learning in teacher education. Educ. Rev. 2015, 67, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparisi, D.; Granados, L.; Sanmartín, R.; Martínez-Monteagudo, M.C.; García-Fernández, J.M. Relationship between emotional intelligence, generativity and self-efficacy in secondary school teachers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, D.A. Actitud al Cambio Socioeducativo y Práctica Educativa. Un Análisis Multifactorial en Población Docente. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain, 2015. Available online: https://roderic.uv.es/handle/10550/47832 (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Hastings, L.J.; Griesen, J.V.; Hoover, R.E.; Creswell, J.W.; Dlugosh, L.L. Generativity in college students: Comparing and explaining the impact of mentoring. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2015, 56, 651–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme-Brevis, H.; Sandoval-Obando, E. Prácticas de movilidad y desempeño laboral del profesorado rural en la Región de La Araucanía, Chile. Rev. Transp. Territ. 2021, 24, 32–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, S.; Zuroff, D.; Moskowitz, D.S. Generativity in midlife and young adults: Links to agency, communion, and subjective well-being. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2000, 50, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, M.D.; Besley, S.C. Teacher identity development in the first year of teacher education: A developmental and social psychological perspective. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2013, 36, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

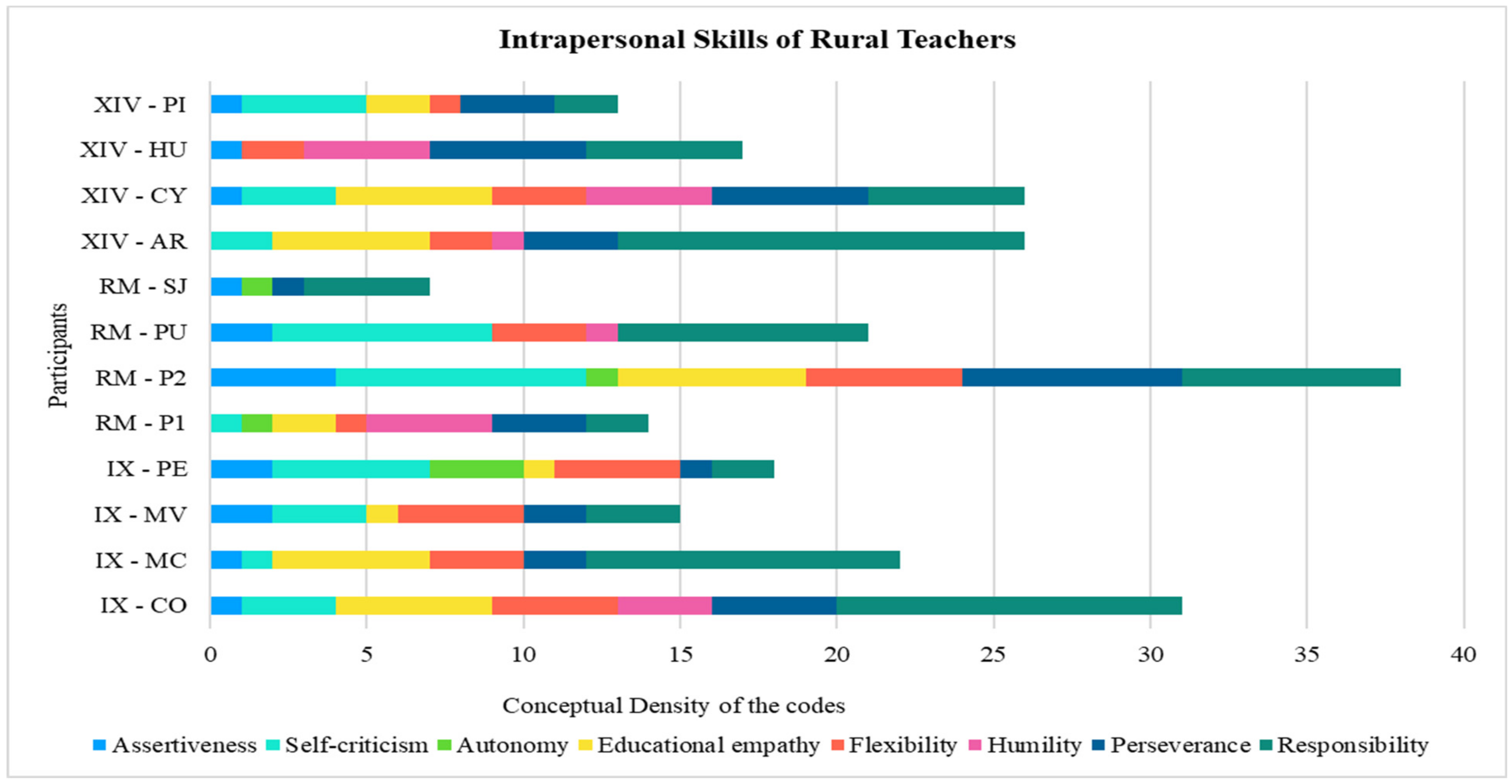

| Codes | IX—CO | IX—MC | IX—MV | IX—PE | RM—P1 | RM—P2 | RM—PU | RM—SJ | XIV—AR | XIV—CY | XIV—HU | XIV—PI | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assertiveness | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 16 |

| Self-criticism | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 37 |

| Autonomy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Educational empathy | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 32 |

| Flexibility | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 32 |

| Humility | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 17 |

| Perseverance | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 36 |

| Responsibility | 11 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 72 |

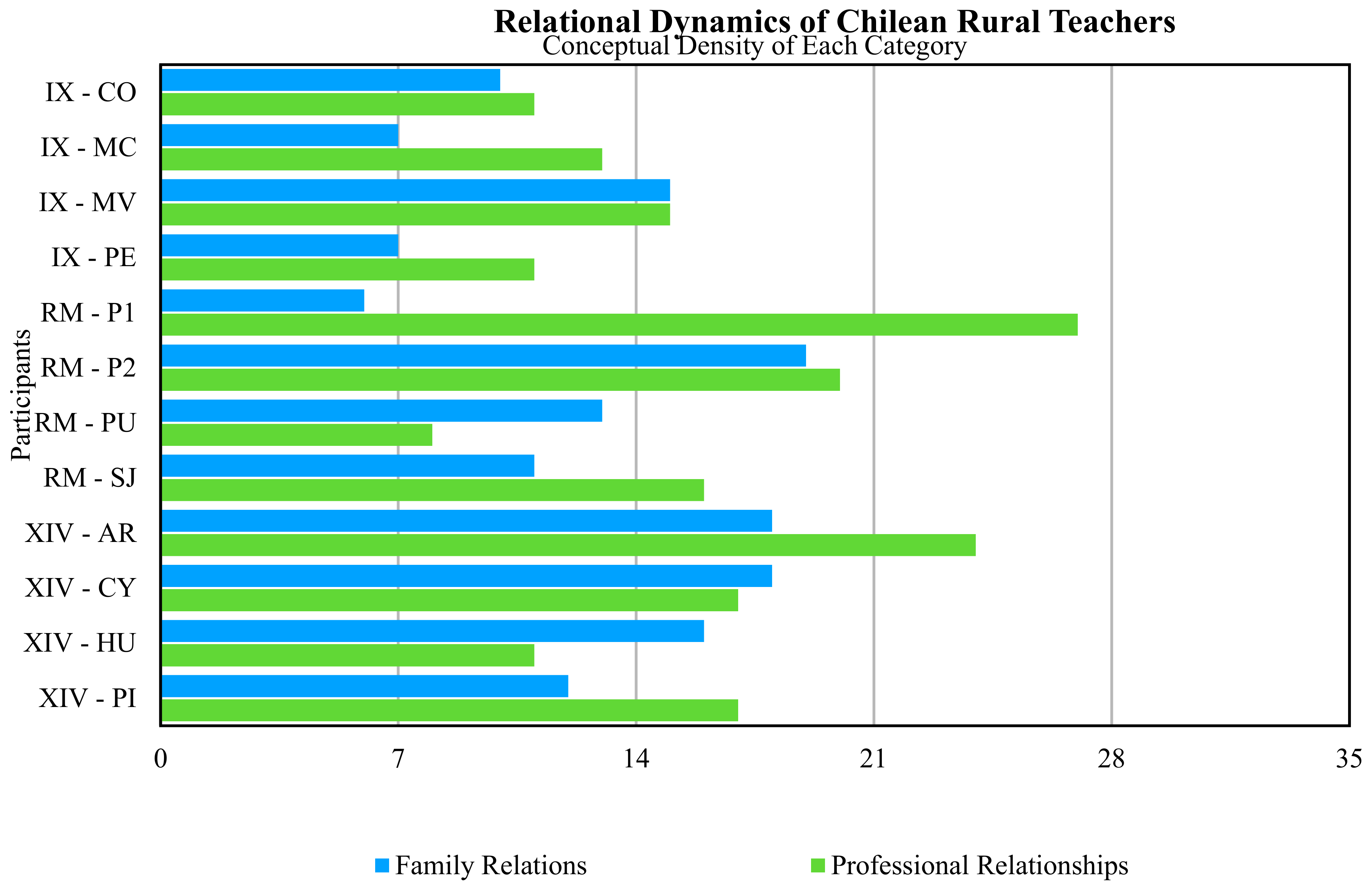

| Codes | IX—CO | IX—MC | IX—MV | IX—PE | RM—P1 | RM—P2 | RM—PU | RM—SJ | XIV—AR | XIV—CY | XIV—HU | XIV—PI | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Relations | 10 | 7 | 15 | 7 | 6 | 19 | 13 | 11 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 12 | 152 |

| Professional Relationships | 11 | 13 | 15 | 11 | 27 | 20 | 8 | 16 | 24 | 17 | 11 | 17 | 190 |

| Total | 21 | 20 | 30 | 18 | 33 | 39 | 21 | 27 | 42 | 35 | 27 | 29 | 342 |

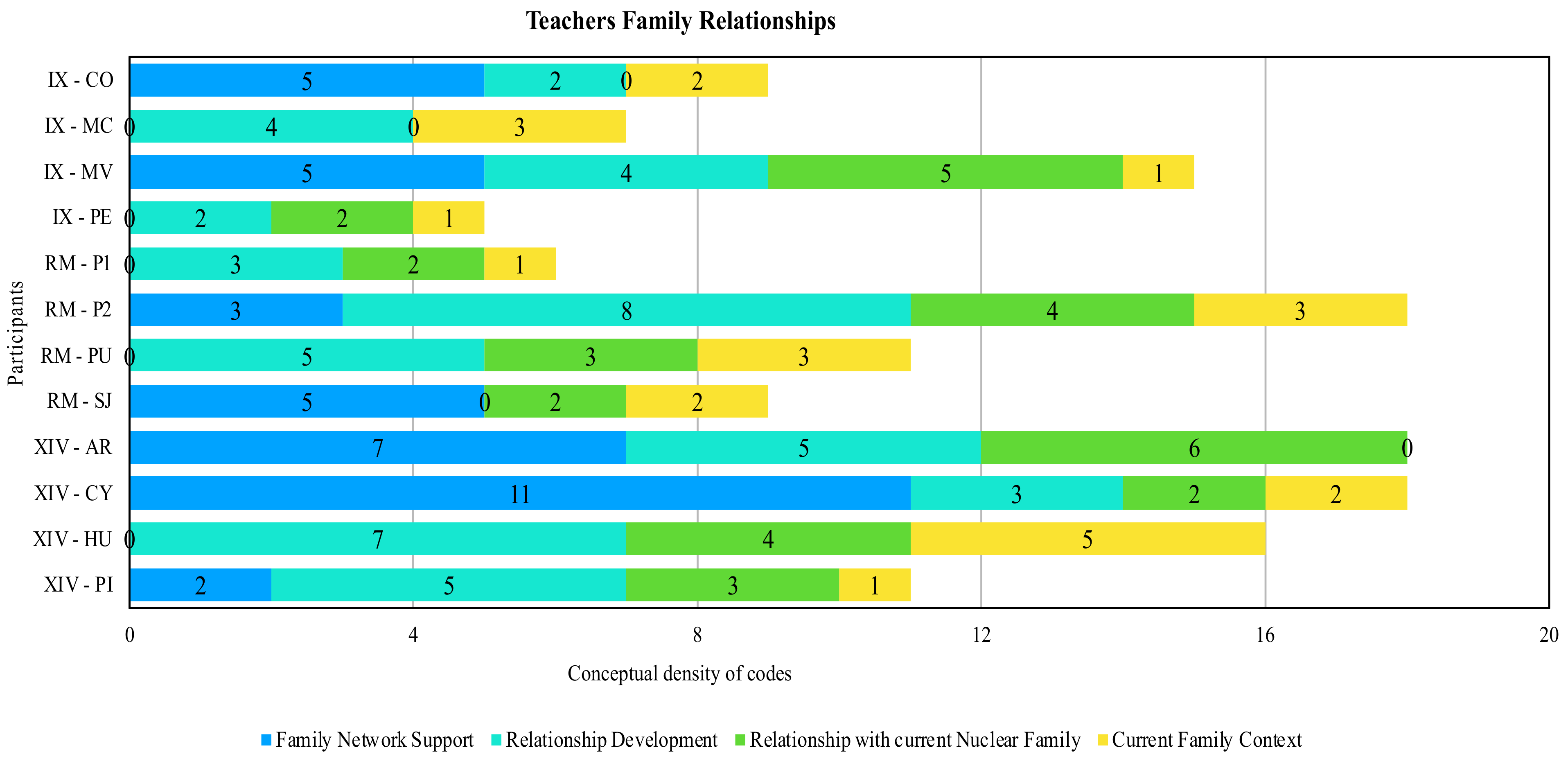

| Codes | IX—CO | IX—MC | IX—MV | IX—PE | RM—P1 | RM—P2 | RM—PU | RM—SJ | XIV—AR | XIV—CY | XIV—HU | XIV—PI | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Network Support | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 11 | 0 | 2 | 38 |

| Relationship Development | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 48 |

| Relationship with current nuclear family | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 33 |

| Current family context | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 24 |

| Total | 9 | 7 | 15 | 5 | 6 | 18 | 11 | 9 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 11 | 143 |

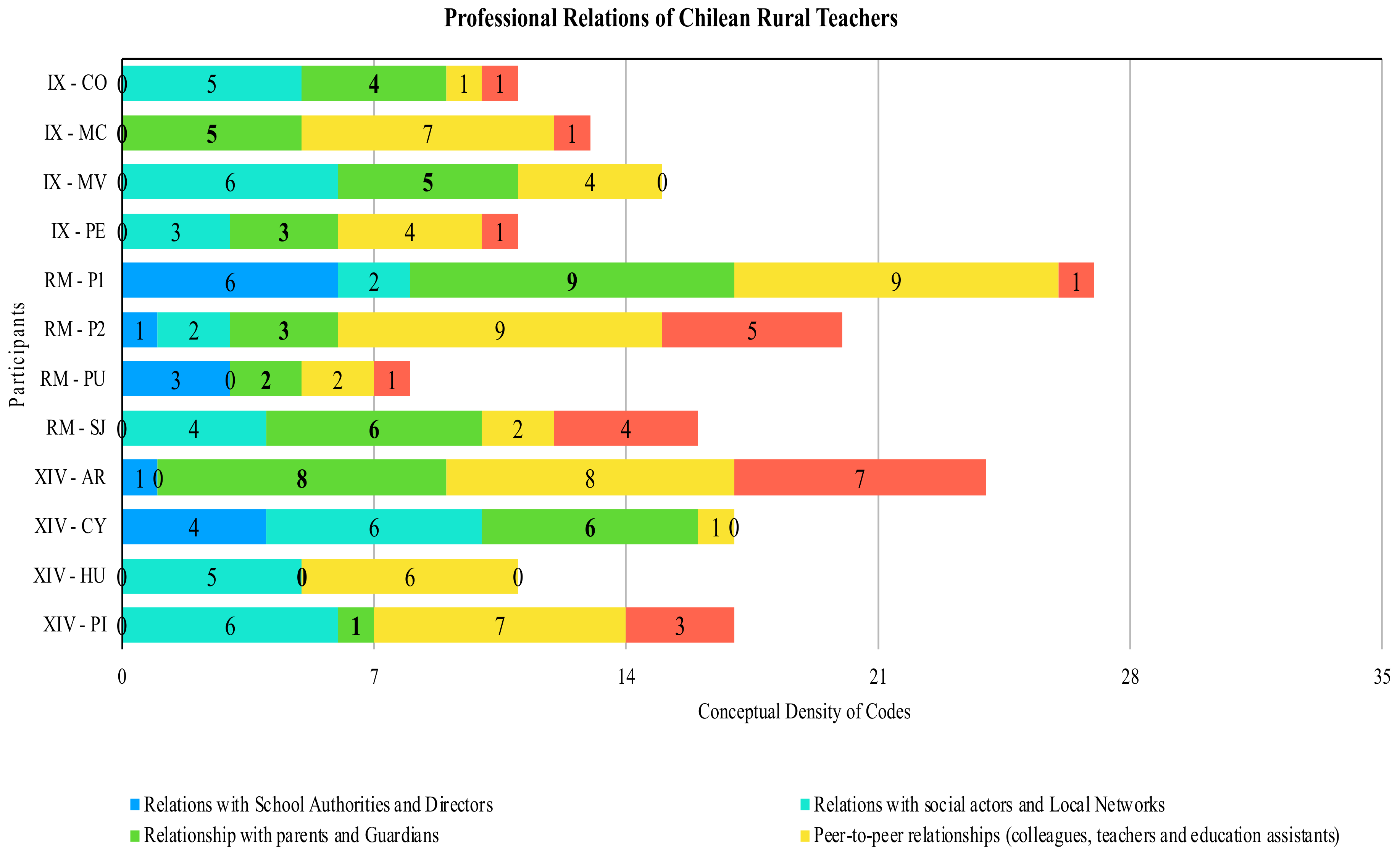

| Codes | IX—CO | IX—MC | IX—MV | IX—PE | RM—P1 | RM—P2 | RM—PU | RM—SJ | XIV—AR | XIV—CY | XIV—HU | XIV—PI | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relations with school authorities and Directors | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| Relations with social actors and local networks | 5 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 39 |

| Relationship with parents and guardians | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 52 |

| Peer to peers relationship (colleagues, teachers, education assistants) | 1 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 60 |

| Relationship with students | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 24 |

| Total | 11 | 13 | 15 | 11 | 27 | 20 | 8 | 16 | 24 | 17 | 11 | 17 | 190 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sandoval-Obando, E.; Pareja Arellano, N.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Riquelme-Brevis, H.; Hernández-Mosqueira, C.; Rivas-Valenzuela, J. Understanding the Relational Dynamics of Chilean Rural Teachers: Contributions from a Narrative-Generative Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8386. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148386

Sandoval-Obando E, Pareja Arellano N, Acevedo-Duque Á, Riquelme-Brevis H, Hernández-Mosqueira C, Rivas-Valenzuela J. Understanding the Relational Dynamics of Chilean Rural Teachers: Contributions from a Narrative-Generative Perspective. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8386. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148386

Chicago/Turabian StyleSandoval-Obando, Eduardo, Nicolás Pareja Arellano, Ángel Acevedo-Duque, Hernán Riquelme-Brevis, Claudio Hernández-Mosqueira, and Johan Rivas-Valenzuela. 2022. "Understanding the Relational Dynamics of Chilean Rural Teachers: Contributions from a Narrative-Generative Perspective" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8386. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148386

APA StyleSandoval-Obando, E., Pareja Arellano, N., Acevedo-Duque, Á., Riquelme-Brevis, H., Hernández-Mosqueira, C., & Rivas-Valenzuela, J. (2022). Understanding the Relational Dynamics of Chilean Rural Teachers: Contributions from a Narrative-Generative Perspective. Sustainability, 14(14), 8386. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148386