Properties of Air Lime Mortar with Bio-Additives

Abstract

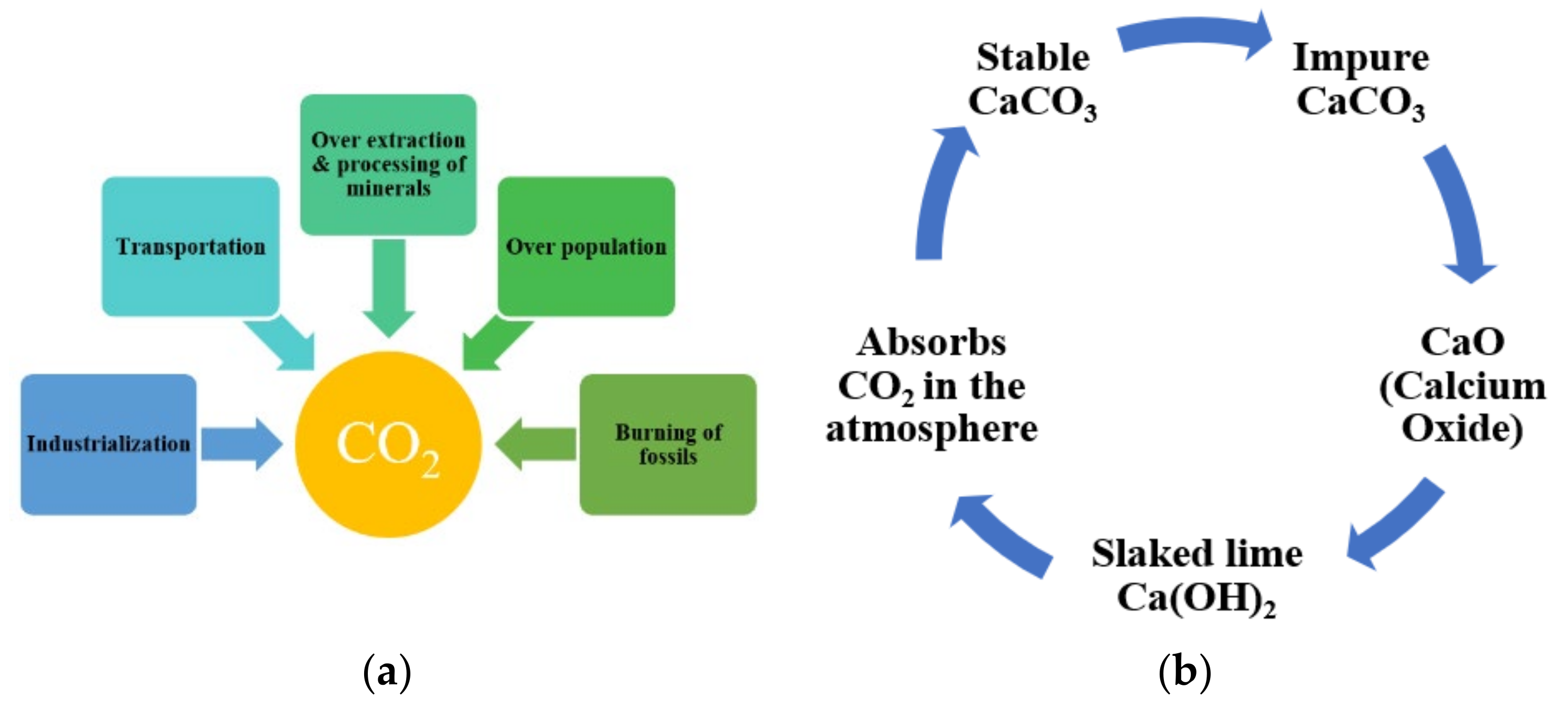

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Fine Aggregate

2.1.2. Lime

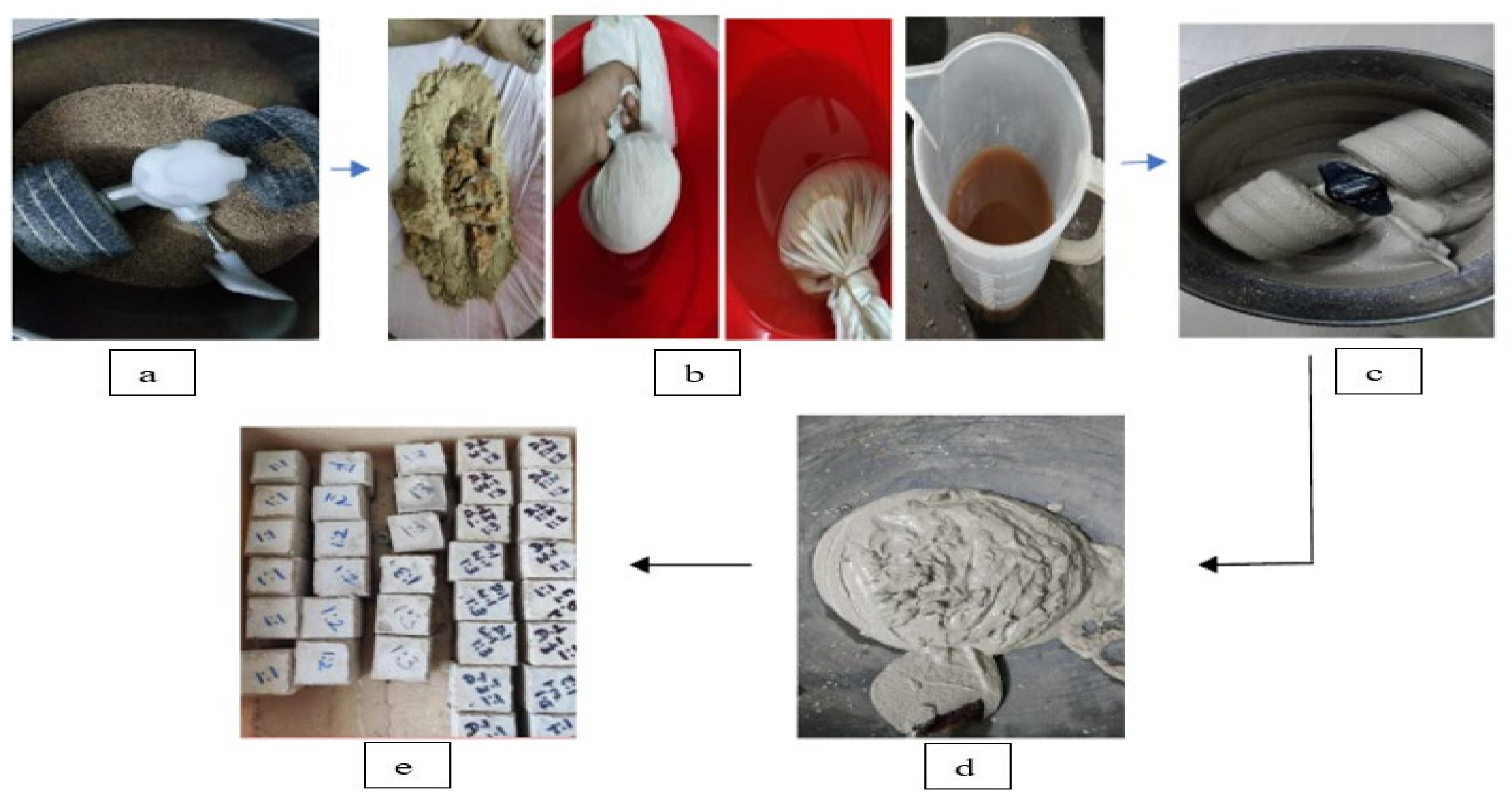

2.1.3. Extract Preparation

2.1.4. Mortar Preparation

2.2. Mechanical Evaluation (Compressive Strength)

2.3. Durability of Mortar

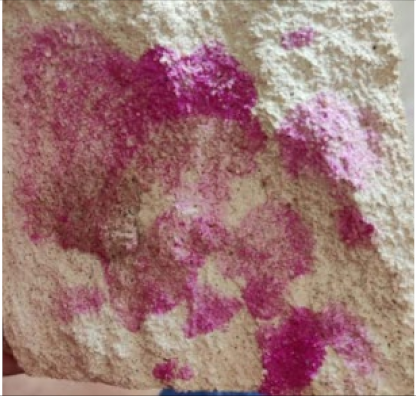

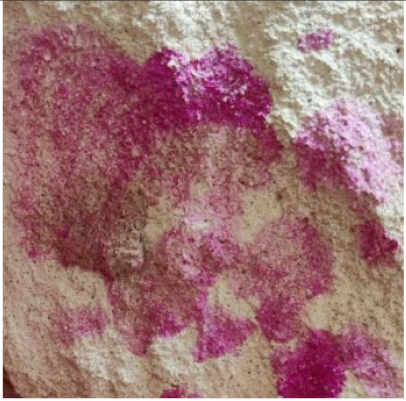

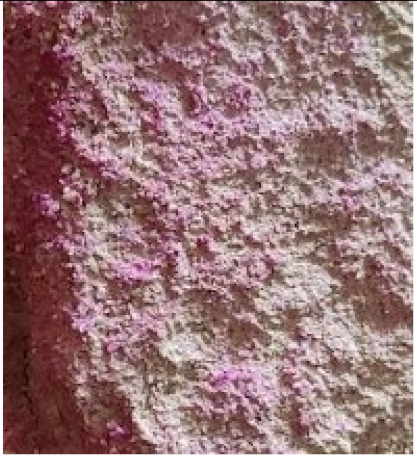

2.3.1. Carbonation (Phenolphthalein Indicator Test)

2.3.2. Water Absorption

2.3.3. Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity Test

3. Mineralogical Characterization of Lime Mortar—SEM Analysis

4. Study on Bio-Additives and Its Composition

5. Results and Discussion

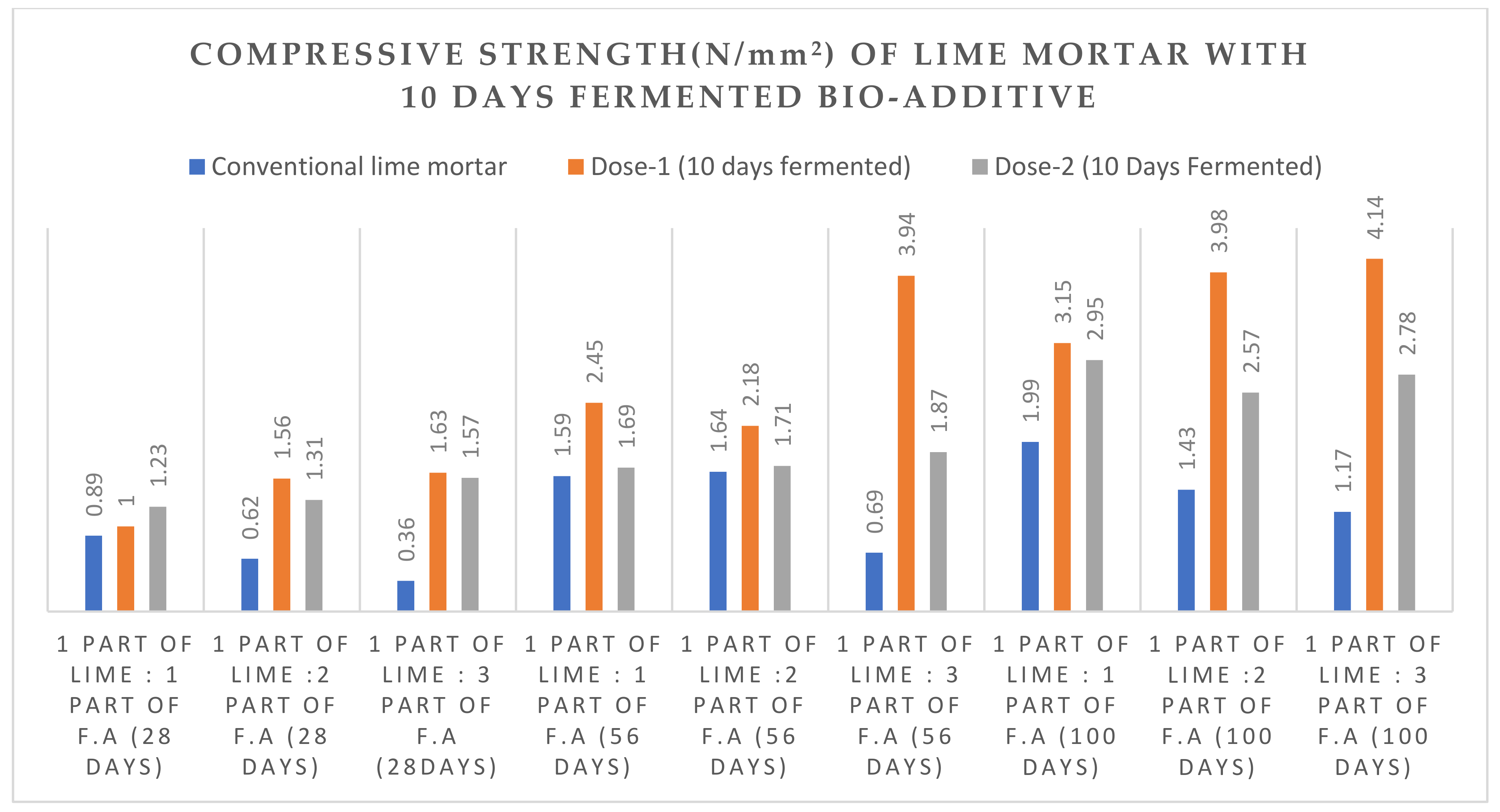

5.1. Strength Properties

5.2. Durability Properties

5.2.1. Water Absorption

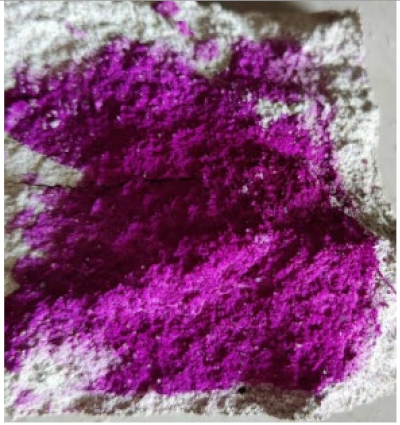

5.2.2. Carbonation (Phenolphthalein Indicator Test)

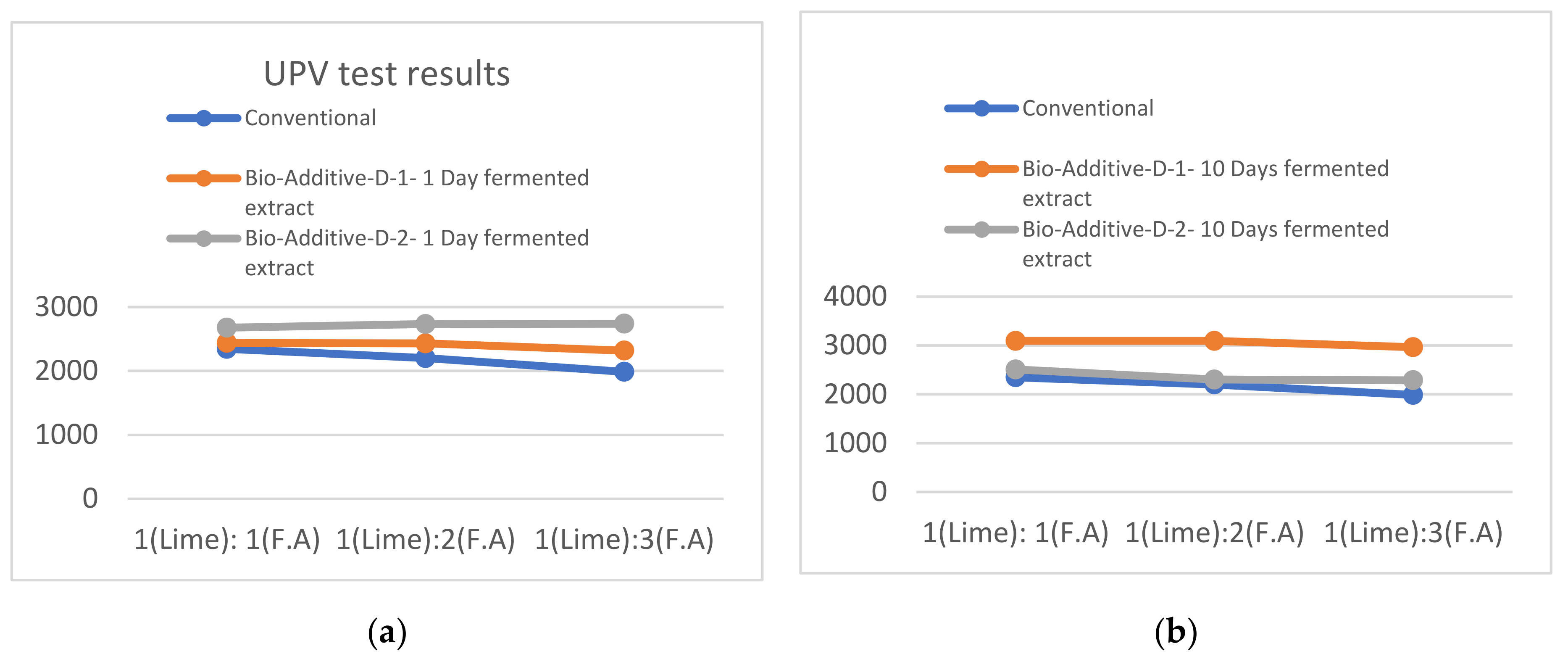

5.2.3. UPV Test

5.3. Mineralogical Characterization of Lime Mortar

5.4. Study on Fermentation of Additives

5.4.1. Phytochemical Analysis

5.4.2. Presence of Proteins, Total Fat, and Ethanol

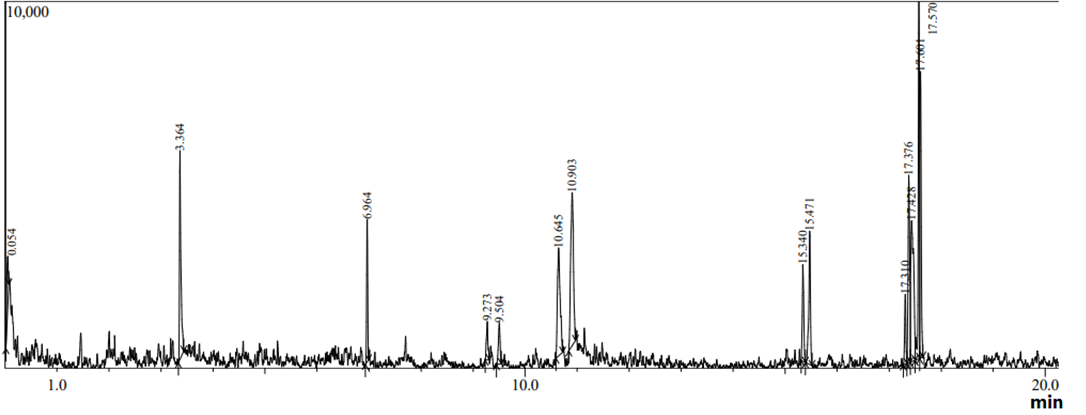

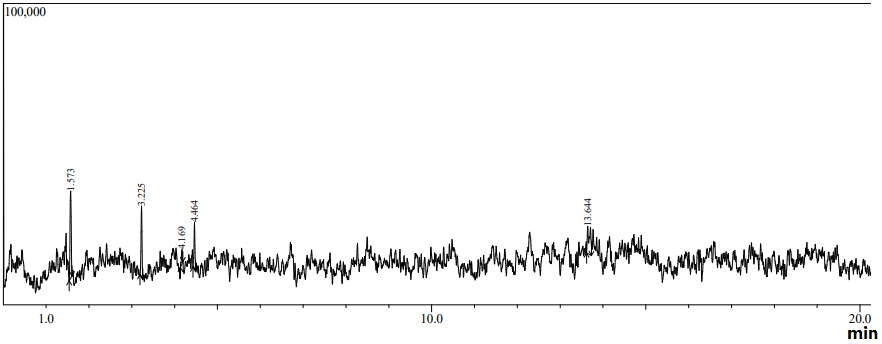

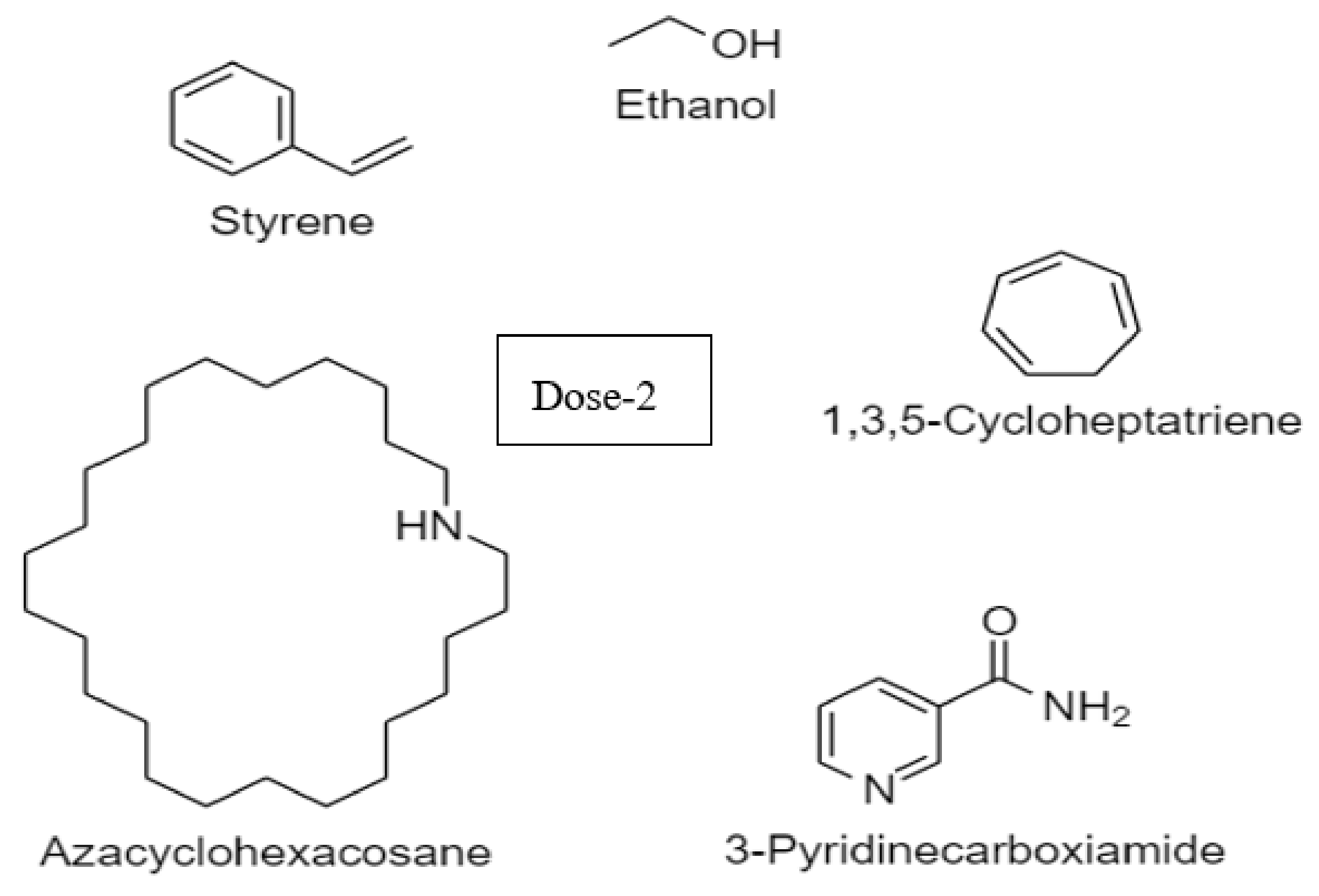

5.4.3. Mass Spectroscopy of the Bio-Additives

6. Conclusions

- The experimental analysis resulted in increased compressive strength of air lime mortar added with bio-additives compared to the conventional air lime mortar. The additives improved the lime matrix property with minimum lime content (1:3 > 1:2 > 1:1) compared to the conventional lime matrix, which depended on the binder content of the matrix (1:1 > 1:2 > 1:3). The use of binder content can be minimized by using fermented additives. The dose 1 fermented bio-additives gave higher strength compared to dose 2, whereas in durability the dose 2 additives had improved carbonation results from the phenolphthalein indicator test;

- The SEM image explains the formation of ettringites all over the sample, proving that hydration happened with the C-S-H phase products, calcium aluminum sulfate, and calcium phosphate, which is the sole reason for the improved strength and durability properties. The SEM analysis relates to the formation of a homogeneous bonding of ingredients present in the lime because these additives led to improved properties. The amorphous crystal formation of calcium oxides depicts the reaction taking place with the carbon dioxide present in the atmosphere. The calcium carbonate, aragonite, and stable forms of vaterite and calcium oxalates prove the carbonation process, as they are excellent carbon-capturing agents in the environmental exposure conditions [60];

- The process of carbonation depends on the capillary pores present in the atmosphere, which lets air move inside the sample. Hence, the UPV test results show that the addition of fermented bio-additives improved the quality of the mortar sample with higher results;

- The in-depth study on fermented bio-additives indicates the presence of proteins and fats. Protein is known for its air-entraining enhancement qualities in the lime mortar and makes it durable in various climatic conditions [61,62,63]. The use of jaggery has been the most primitive way of construction, which has given excellent results in the hardening process in the matrix material [64]. The fat content in the additives is soluble in alcohol forms, as the fermentation time of the extract increases the lime mortar, which gains an increased carbonation process, and the carbohydrates are soluble in water and improve the carbonation rate. Hence, both fats and carbohydrates improve the strengthening process overall [65];

- The 3-Pyridinecarboxiamide, N-[3-Methyl-1-((phenylmethyl) are glucokinase activators that activate the carbohydrate metabolism, leading to improved carbonation in the lime mortar, resulting in increased strength achievement;

- The process of fermentation is hence a cost-efficient, non-toxic, and natural process that enhances the properties of bio-additives from the experimental analysis that gives strength and durability properties to the lime mortar [58];

- The laboratory exposure conditions have less carbon dioxide present in the atmosphere; exposing these specimens to polluted areas will make them gain more strength since the rate of carbonation is higher with higher carbon dioxide presence;

- The use of these lime mortars in plastering works will be the initial step toward the use of sustainable construction materials, bringing in a vast scope for researchers to improve the setting time properties of lime for further use in the construction works and in the preservation of ancient constructions as a compatible repair material [66].

- The research results also encourage people to do extensive research on utilizing naturally available bio-additives and less processed materials, bringing in the best properties of locally available materials for an environmentally friendly and healthy lifestyle.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Almendra Freitas, J., Jr.; de Mello Maron, M.D.R.; Artigas, L.V.; Martins, L.; Sanquetta, C.R. Assessment of the impact of binders in the evolution of carbonation in mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 225, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chena, Y.; Huanga, B.; Huangb, M.; Lua, Q.; Huang, B. Sticky rice lime mortar-inspired in situ sustainable design of novelcalcium-rich activated carbon monoliths for efficient SO2 Capture. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, e449–e457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carran, D.; Hughes, J.; Leslie, A.; Kennedy, C. A Short History of the Use of Lime as a Building Material—Beyond Europe and North America. Beyond Europe. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2012, 6, 117–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IS 712; Specification for Building Limes. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 1984.

- Santarelli, M.L.; Sbardella, F.; Zuena, M.; Tirillò, J.; Sarasini, F. Basalt fiber reinforced natural hydraulic lime mortars: A potentialbio-based material for restoration. Mater. Des. 2014, 63, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasingh, S.; Baby, J. Influence of organic addition on strength and durability of lime mortar prepared with clay aggregate. Mater. Today Proc. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuixiong, L.; Linyi, Z.; Li, L.; Jinua, W. Zuixiongetal Research on the modification of two traditional building materials in ancient China. Herit. Sci. 2013, 1, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rehan, R.; Nehdi, M. Carbon dioxide emissions and climate change: Policy implications for the cement industry. Environ. Sci. Policy 2005, 8, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.; Zhoua, J.; Yanga, F.; Lanb, M.; Lic, J.; Zhangd, Z.; Chend, Z.; Xua, M.; Lia, H.; Sanjayan, J.G. Analysis of theoretical carbon dioxide emissions from cement production: Methodology and application Song. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 334, 130270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhelal, E.; Shamsaei, E.; Rashid, M.I. Challenges against CO2 abatement strategies in cement industry: A review. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 104, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Chakraborty, A.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y. Editorial Impacts of Climate Change on Biological Dynamics. Hindawi Publ. Corp. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2016, 2016, 9046107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonneuila, C.; Choquetb, P.; Franta, B. Early warnings and emerging accountability: Total’s responses to global warming. 1971–2021. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 71, 102386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneefa, K.M.; Rani, S.D.; Ramasamy, R.; Santhanam, M. Microstructure and geochemistry of lime plaster mortar from a heritage structure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 225, 538–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalini, P.; Ravi, R.; Sekar, S.K.; Nambirajan, M. Study on the performance enhancement of lime mortar used in ancient temples and monuments in India. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2011, 4, 1484–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasingh, S.; Selvaraj, T. Effect of Natural Herbs on Hydrated Phases of Lime Mortar. J. Archit. Eng. 2020, 26, 04020021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar, M.; Selvaraj, T.; Dhassaih, M.P. Preparation and characterization of the ancient recipe of organic Lime Putty-Evaluation for its suitability in restoration of Padmanabhapuram Palace, India. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizzia, A.; Vilesb, H.; Cultrone, G. Experimental testing of the durability of lime-based mortars used for rendering historic buildings. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 28, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanas, J.; Alvarez, J.I. Masonry repair lime-based mortars: Factors affecting the mechanical behavior. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 1867–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ventolà, L.; Vendrell, M.; Giraldez, P.; Merino, L. Traditional organic additives improve lime mortars: New old materials for restoration and building natural stone. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 3313–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanas, J.; Bernal, J.L.P.; Bello, M.A.; Alvarez, J.I. Mechanical properties of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 2191–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frankeová, D.; Koudelková, V. Influence of ageing conditions on the mineralogical micro-character of natural hydraulic lime mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 264, 120205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IS 2386; Methods of Test for Aggregates for Concrete (Part I). Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 1963.

- IS 383; Specification for Coarse and Fine Aggregates from Natural Sources for Concrete. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 1970.

- IS 2386; Methods of Test for Aggregates for Concrete (Part III). Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 1963.

- Eckel, E.C. Cements, Limes and Plasters; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2005; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, H. Cement Chemistry; Thomas Telford: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.; Pereira, A.S.; Lemos, P.C.; Guerra, J.P.; Silva, V.; Faria, P. Effect of innovative products in air lime mortars. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 35, 101985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugavel, D.; Dubey, R.; Ramadoss, R. Use of natural polymer from the plant as an admixture in hydraulic lime mortar masonry. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 30, 101252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwanga, H.-Y.; Kwona, Y.-H.; Hongb, S.-G.; Kang, S.-H. Comparative study of effects of natural organic additives and cellulose ether on properties of lime-clay mortars. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 48, 103972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IS: 2250-1981; Code of Practice for Preparation and Use of Masonry Mortars. Indian standard: New Delhi, India, 1981.

- IS:4031 (Part 8); Methods of Physical Tests for Hydraulic Cement. Indian standard: New Delhi, India, 1988.

- IS 2541-1991; Preparation and Use of Lime Concrete-Code of Practice (Second Revision). Indian standard: New Delhi, India, 1991.

- IS 10078-1982; Specification for Jolting Apparatus Used for Testing Cement. Indian standard: New Delhi, India, 1982.

- IS:6932; Methods of Tests for Building Limes, Determination of Unhydrated Oxide (Part V). Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 1973.

- IS:6932; Methods of Tests for Building Limes—Determination of Compressive and Transverse Strengths (Part VII). Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 1973.

- Singha, M.; Arbad, R.B. Characterization of traditional mud mortar of the decorated wall surfaces of Ellora caves. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 65, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, R.S.M.S.; Avudaiappan, S.; Amran, M.; Aepuru, R.; Vatin, N.; Fediuk, R. The Effect of Superabsorbent Polymer and Nano-Silica on the Properties of Blended Cement. Crystals 2021, 11, 1394. [Google Scholar]

- Bokea, H.; Akkurt, S. Ettringite formation in historic bath brick–lime plasters. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 1457–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borgesa, C.; Silvab, A.S.; Veiga, R. Durability of ancient lime mortars in humid environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 66, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazea, C.R.; Adesinad, A.; Lecomte-Nanab, G.L.; Metekongc, J.V.S.; Samenc, L.v.K.; Kamseuc, E.; Melo, U.C. Synergetic effect of rice husk ash and quartz sand on microstructural and physical properties of laterite clay based geopolymer. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, C.; Song, S.; López–Valdivieso, A. Lime mortars—The role of carboxymethyl cellulose on the crystallization of calcium carbonate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 168, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enríqueza, E.; Torres-Carrasco, M.; Cabreraa, M.J.; Muñoza, D.; Fernández, J.F. Towards more sustainable building based on modified Portland cements through partial substitution by engineered feldspars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 269, 121334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Wang, Z.; Yao, J.; Cong, X.; Anning, C.; Lyu, X. Pozzolanic activity and hydration properties of feldspar after mechanical activation. Powder Technol. 2021, 383, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Carrascoa, M.; Enríqueza, E.; Terrón-Menoyoa, L.; Cabrerac, M.J.; Muñozc, D.; Fernández, J.F. Improvement of thermal efficiency in cement mortars by using synthetic feldspars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 269, 121279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IS 7219; Method for Determination of Protein in Foods and Feeds. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 1973.

- Romero-Hermida, M.I.; Borrero-Lopez, A.M.; Flores-Ales, V.; Alejandre, F.J.; Franco, J.M.; Santos, A.; Esquivias, L. Characterization and analysis of carbonation process of lime mortar obtained from Phosphogypsum waste. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Negi, P.B.; Sahoo, N.G. Phytochemical screening and characterization of bioactive compounds from Juniperus Squamata root extract. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 48, 672–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P.; Khare, T.; Shriram, V.; Bae, H.; Kumar, V. Plant synthetic biology for producing potent Phyto-antimicrobials to combat antimicrobial resistance. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 48, 107729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.; Das, G. Bio-inspired synthesis of flavonoids incorporated CaCO3: Influence on the composites’ phase, morphology, and mechanical strength. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 642, 128720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiana, C.K.; Songa, Y.; Laia, J.; Qiana, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, Y.; Ruan, S. Characterization of historical mortar from ancient city walls of Xindeng in Fuyang. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 315, 125780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takuli, N.P.; Khulbe, K.; Kumar, P.; Parki, A.; Syed, A.; Elgorban, A.M. Phytochemical profiling, antioxidant and antibacterial efficacy of a native Himalayan Fern: Woodwardia unigemmata (Makino). Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 1961–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Zhuang, T.; Fu, P.; Zhou, Q.; Luo, L.; Dong, Z.; Li, H.; Tang, S. Alpha-terpineol grafted acetylated lentinan as an anti-bacterial adhesion agent. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 277, 118825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Ujihara, H.; Watanabe, S.; Harada, M.; Matsuda, H.; Hagiwara, T. Synthesis and odr of optically active trans-2,2,6-trimethyl cyclohexyl methyl ketones and their related compounds. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, A.; Praveenkumar, R.; Thangaraj, R.; Oscar, F.L.; Baldev, E.; Dhanasekaran, D.; Thajuddin, N. Microalgal fatty acid methyl ester a new source of bioactive compounds with antimicrobial. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2014, 4, S979–S984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, T.W.; Höfer, R. Lipid-Based Polymer Building Blocks and Polymers. In Polymer Science: A Comprehensive Reference; 10 Volume Set; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Salman, H.N.K. Antimicrobial activity of the compound 2-Piperidinone,N-[4-Bromo-n-butyl]-Extracted from pomegranate peels. Asian J. Pharm. 2019, 13, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ridaoui, K.; Guenaou, I.; Taouam, I.; Cherki, M.; Bourhim, N.; Elamrani, A.; Kabine, M. Comparative study of the antioxidant activity of the essential oils of five plants against the H2O2 induced stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 1842–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradeep, S.; Gummadi, S.; Selvaraj, T. Living mortars-simulation study on organic lime mortar used in heritage structures. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2022, 137, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, M.; Nonoshita, K.; Ogino, Y.; Nagae, Y.; Tsukahara, D.; Hosaka, H.; Maruki, H.; Ohyama, S.; Yoshimoto, R. Discovery of novel 2-(pyridine-2-yl)-1H-benzimidazole derivatives as potent glucokinase activators. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 4450–4454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco-Coppi, M.; Hofmann, C.; Ströhle, J.; Walter, D.; Epple, B. Efficient CO2 capture from lime production by an indirectly heated carbonate looping process. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2021, 112, 103430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliozzo, E.; Pizzo, A.; La Russa, M.F. Mortars, plasters and pigments—Research questions and sampling criteria. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2021, 13, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugavel, D.; Kumar, Y.P.; Khadimallah, M.A.; Ramadoss, R. Experimental analysis on the performance of egg albumen as a sustainable bio admixture in natural hydraulic lime mortars. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, R.; Thirumalini, S.; Taher, N. Analysis of ancient lime plasters—Reason behind longevity of the Monument Charminar, India a study. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 20, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintea, A.; Manea, D. New types of mortars obtained by aditiving traditional mortars with natural polymers to increase physicomechanical performances. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 32, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shasavandi, A.; Salavessa, E.; Torgal, F.P.; Jalali, S. Air Lime Mortars with Vegetable Fat Addition: Characteristics and Research Needs. In Proceedings of the 2nd Historic Mortars Conference HMC2010 and RILEM TC 203-RHM Final Workshop, Prague, Czech Republic, 22–24 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Manoharan, A.; Umarani, C. Review Lime Mortar, a Boon to the Environment: Characterization Case Study and Overview. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Test Result | IS Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Fineness modulus | 2.592 | IS: 2386 (Part I)–1963 [22] |

| Grading zone | Zone II | IS codes (IS: 383-1970) [23] |

| Specific gravity | 2.55 | IS 2386(Part-III): 1963 [24] |

| Constituents | % of Presence |

|---|---|

| MgO | 2.3 |

| SiO2 | 5.78 |

| CaO | 60.22 |

| Al2O3 | 1.76 |

| Fe2O3 | 1.349 |

| Sulphur | 0.37 |

| Potassium | 0.21 |

| Ratio | Mortar Mix Name | Mortar Details | Extract Details | Fermentation Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:1 | LMA | Conventional lime mortar | Only water | - |

| 1:2 | LMB | |||

| 1:3 | LMC | |||

| 1:1 | FLM-1-D | 1-day fermented dose 1 bio-additive | Dose 1: 25 gm Jaggery and 25 gm of kadukkai for 1 L of water | 1 day |

| 1:2 | FLM-1-E | |||

| 1:3 | FLM-1-F | |||

| 1:1 | FLM-2-D | 1-day fermented dose 2 bio-additive | Dose 2: 50 gm Jaggery and 50 gm kadukkai for 1 L of water | 1 day |

| 1:2 | FLM-2-E | |||

| 1:3 | FLM-2-F | |||

| 1:1 | FLM-1-G | 10-day fermented dose 1 bio-additive | Dose 1: 25 gm Jaggery and 25 gm of kadukkai for 1 L of water | 10 days |

| 1:2 | FLM-1-H | |||

| 1:3 | FLM-1-I | |||

| 1:1 | FLM-2-G | 10-day fermented dose 2 bio-additive | Dose 2: 50 gm Jaggery and 50 gm kadukkai for 1 L of water | 10 days |

| 1:2 | FLM-2-H | |||

| 1:3 | FLM-2-I |

| S.NO | Mix Ratio | Role of Mortar Mix Ratio in the Site of Renovation Work (As Inspected and Heard from the Traditional Renovation Workers) | Conventional Lime Mortar (W/L Ratio) | Fermented Bio-Additives (W/L Ratio) | Fermented Bio-Additives (W/L Ratio) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose 1 | Dose 2 | Dose 1 | Dose 2 | ||||

| 1 | 1:1 | Minute architectural renovations | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.70 |

| 2 | 1:2 | Beam-column joints and pointing works | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.75 |

| 3 | 1:3 | Wall plastering and pointing works | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.76 |

| S. No | Parameters | Method |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Proteins | IS 7219-1973 [45] |

| 2 | Fat | AOAC METHOD |

| 3 | Ethanol | Gas chromatography |

| S. No | Sample Details | Phenolphthalein Indicator Test Results | Inference | Carbonation Depth (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LMA |  | Unreacted Cao, yet to be activated by carbon dioxide absorption | 2 cm |

| 2 | LMB |  | Unreacted Cao, yet to be activated by carbon dioxide absorption, the lower side is carbonated to some extent. | 2.5 cm |

| 3 | LMC |  | The upper exposed area is carbonated, while the other part is yet to be carbonated. | 2.2 cm |

| 4 | FLM-1-D |  | Portlandite and calcite | 2 cm |

| 5 | FLM-1-E |  | Unreacted Cao, yet to be activated by carbon dioxide absorption | 3 cm |

| 6 | FLM-1-F |  | Scattered carbonation process showing the presence of portlandite and calcite | 4 cm |

| 7 | FLM-2-D |  | Portlandite and calcite | 4.2 cm |

| 8 | FLM-2-E |  | Formation of major amount of portlandite and calcite | 3.5 cm |

| 9 | FLM-2-F |  | Almost all of the surrounding areas are carbonated while internally it is yet to be carbonated. | 2.9 cm |

| 10 | FLM-1-G |  | Unreacted Cao, yet to be activated by carbon dioxide absorption | 2.4 cm |

| 11 | FLM-1-H |  | Scattered carbonation process | 3 cm |

| 12 | FLM-1-I |  | Complete carbonation process with the formation of Calcite | Fully carbonated |

| 13 | FLM-2-G |  | Partially carbonated sample | 3.6 cm |

| 14 | FLM-2-H |  | Presence of portlandite and calcite | 2 cm |

| 15 | FLM-2-I |  | Presence of portlandite and calcite | 2.7 cm |

| Test | Bio-Additives at 1 Day of Fermentation | Bio-Additives at 10 Days of Fermentation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose 1 | Dose 2 | Dose 1 | Dose 2 | |

| Alkaloids | − | + | + | + |

| Terpenoids | + | + | + | + |

| Steroid | − | − | − | − |

| Phenol | + | + | + | + |

| Flavonoids | + | + | + | + |

| Tannins | + | + | + | + |

| Glycosides | + | + | + | + |

| Saponins | − | − | + | − |

| Sample | OD AT 570 nm | QE (µg/mg) |

|---|---|---|

| Dose 1 | 0.128 | 15.31 |

| Dose 2 | 0.158 | 18.9 |

| Sample | OD AT 765 nm | GAE (µg/mg) |

|---|---|---|

| Dose 1 | 1.119 | 575.96 |

| Dose 2 | 1.115 | 573.89 |

| S. No | Parameters | Method | Results (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fermented (1 Day) Dose 1 | Fermented (1 Day) Dose 2 | Fermented (10 Days) Dose 1 | Fermented (10 Days) Dose 2 | |||

| 1 | Proteins | IS 7219-1973 | 0.2885 | 0.2885 | 0.162 | 0.538 |

| 2 | Total Fat | AOAC METHOD | 3.723 | 3.453 | 1.3433 | 1.395 |

| 3 | Ethanol | Gas Chromatography | Not Detected | Not Detected | Not Detected | 34.1 |

| S. No | R. Time | Peak Height % | Constituent | Molecular Weight | Role of the Constituent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.054 | 2.59 | 1,2-Epoxynonane | 142.24 | Solvent stabilizers, plasticizers, organics synthesis |

| 2 | 3.364 | 10.29 | Formamide, N,N-dimethyl- | 73.038 | Solvent |

| 3 | 6.964 | 7.01 | Alpha.-Terpineol | 154 | Anti-bacterial adhesion and anti-biofilm agent [52] |

| 4 | 9.273 | 1.89 | Benzene, 1,3-dibromo-2-methoxy- | 264 | Photocatalyst |

| 5 | 9.504 | 2.03 | Beta.-D-Fructopyranose, 2,3:4,5-bis-O-(1-met) | 260 | Odor |

| 6 | 10.645 | 5.31 | Tetrahydroionyl acetate | 240 | Odor |

| 7 | 10.903 | 7.55 | 1-(2,2,6-Trimethylcyclohexyl) hexan-3-ol | 226 | Odor [53] |

| 8 | 15.340 | 4.77 | Pentadecanoic acid,14-methyl-, methyl ester | 270 | Fatty acid [54] |

| 9 | 15.471 | 6.57 | Pentadecanoic acid,14-methyl-, methyl ester | 270 | Fatty acid [54] |

| 10 | 17.310 | 3.45 | 11,14-Eicosadienoic acid | 322 | Omega fatty acid |

| 11 | 17.376 | 9.23 | 6-Octadenoic acid, methyl [53] ester, (Z)- | 296 | The solvent in herbicide and pesticide |

| 12 | 17.428 | 6.94 | 7-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester | 296 | The solvent in herbicide and pesticide |

| 13 | 17.570 | 18.24 | Methyl stearate | 298 | A fatty acid ester [55] |

| 14 | 17.601 | 14.12 | Methyl stearate | 298 | A fatty acid ester [55] |

| S. No | R.Time | Peak Height % | Constituent | Molecular Weight | Role of the Constituent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.052 | 14 | 2-Piperidinone, N-[4-bromo-n-butyl]- | 233 | Antimicrobial quality [56] |

| 2 | 3.226 | 63 | Toluene | 92 | As a solvent and in organic synthesis |

| 3 | 3.369 | 6.25 | Formamide, N, N-dimethyl- | 73 | Odor |

| 4 | 4.168 | 3.61 | Ethylbenzene | 106 | Helps in the formation of styrene |

| 5 | 4.446 | 6.23 | Styrene | 104 | Odor |

| 6 | 5.670 | 2.64 | Cyclobutene, 1,2-bis(1-methylethenyl)-, trans- | 136 | Antioxidant [57] |

| 7 | 6.029 | 3.37 | Cyclobutene, 1,2-bis(1-methylethenyl)-, trans- | 136 | Antioxidant [57] |

| S. No | R. Time | Peak Height % | Constituent | Molecular Weight | Role of the Constituent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.573 | 35.44 | Ethanol | 46 | Enhances carbonation [58] |

| 2 | 3.225 | 28.75 | 1,3,5-Cycloheptatriene | 92 | Odor |

| 3 | 4.169 | 5.89 | 3-Pyridinecarboxiamide, N-[3-Methyl-1-(phenylmethyl) | 292 | Glucokinase activators [59] |

| 4 | 4.464 | 18.86 | Styrene | 104 | Aromatic liquid hydrocarbon |

| 5 | 13.644 | 11.06 | Azacyclohexacosane | 365 | Helps in ethanol group formation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manoharan, A.; Umarani, C. Properties of Air Lime Mortar with Bio-Additives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8355. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148355

Manoharan A, Umarani C. Properties of Air Lime Mortar with Bio-Additives. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8355. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148355

Chicago/Turabian StyleManoharan, Abirami, and C. Umarani. 2022. "Properties of Air Lime Mortar with Bio-Additives" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8355. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148355

APA StyleManoharan, A., & Umarani, C. (2022). Properties of Air Lime Mortar with Bio-Additives. Sustainability, 14(14), 8355. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148355