Students’ E-Learning Domestic Space in Higher Education in the New Normal

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. New Learning Spaces and ICT

1.2. Current Study

- RQ1: What are the elements found in the physical learning space of HE students in their homes?

- RQ2: Which rooms are used by students for e-learning?

- RQ3: What are the features of the rooms based on the academic components they contain?

- RQ4: What are the spatial relationships between the home and the digital screens used?

- RQ5: What are the screen backgrounds used by students during online training connections?

- RQ6: What is the relationship between the analysed variables?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Data Collection

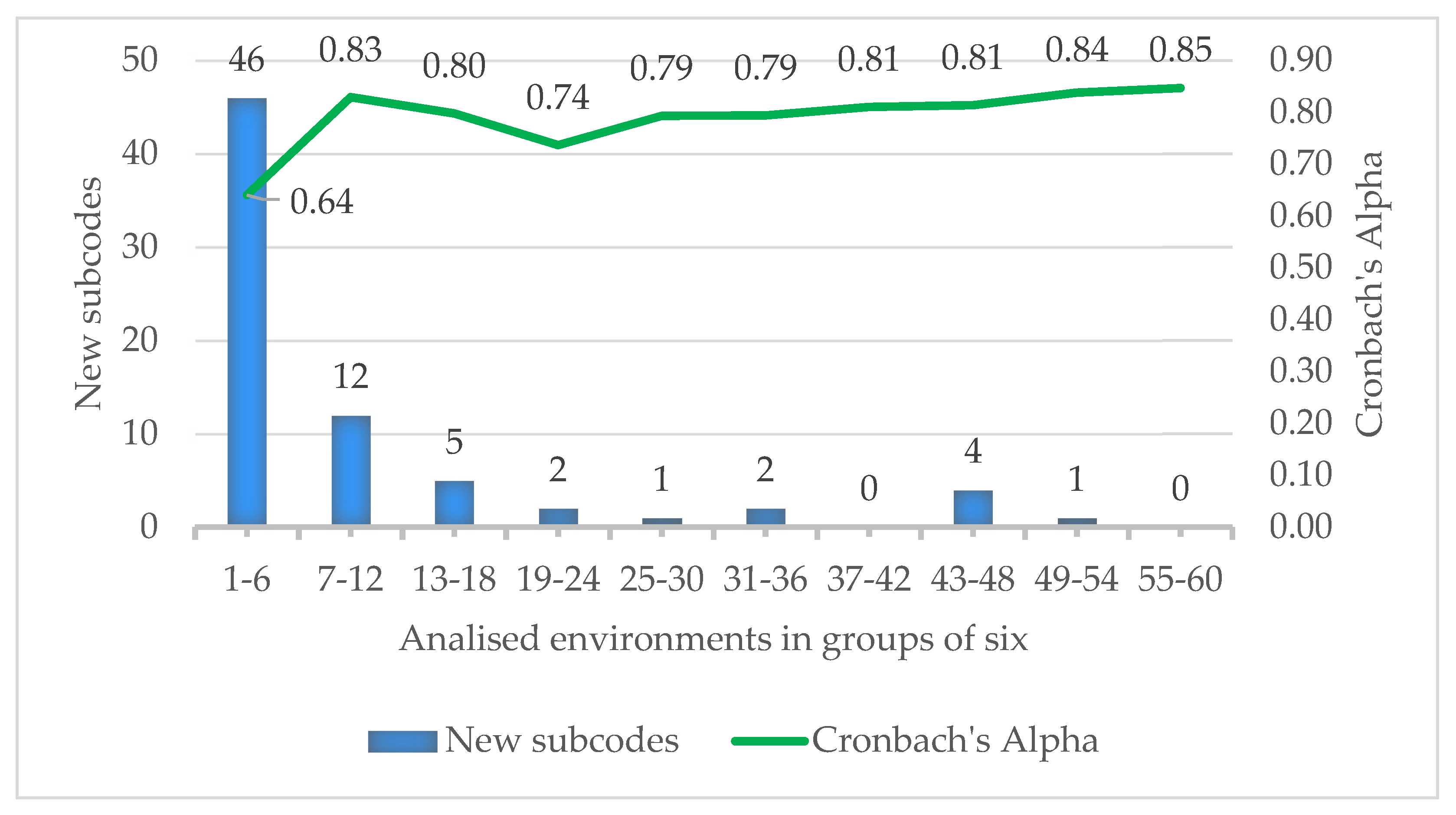

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Everyday Household Items Used by Students (RQ1)

3.2. Rooms Used to Study in the Domestic Scenario and Their Transformation (RQ2, RQ3)

- Bedroom (59%), of which 61% have an average area of between 10 and 15 m2;

- Study (25%), of which 53% have an average area of between 10 and 15 m2;

- Living room (6%), of which 50% have an average area of between 15 and 20 m2;

- Kitchen (2%), very rarely.

3.3. Spatial Relationship of Digital Screens in the Home and Backgrounds Seen during Connections (RQ4, RQ5)

3.4. Associations between Variables (RQ6)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, Y. Does information and communication technology (ICT) empower teacher innovativeness: A multilevel, multisite analysis. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2021, 69, 3009–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.I. Perception on the Adoption of WhatsApp for Learning amongst University Students’. Int. J. Res. STEM Educ. 2021, 3, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-Rocca, A. Peter Sloterdijk: Espumas, mundo poliesférico y ciencia ampliada de invernaderos. Nómadas. Rev. Crítica Cienc. Soc. Jurídicas 2008, 18, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Sloterdijk, P. Esferas III: Espumas; Siruela: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D.; Gregory, K. The use of mobile learning in PK-12 education: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2017, 110, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Vanijja, V. Perceived usability evaluation of Microsoft Teams as an online learning platform during COVID-19 using system usability scale and technology acceptance model in India. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mircea, M.; Stoica, M.; Ghilic-Micu, B. Investigating the impact of the internet of things in higher education environment. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 33396–33409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.; Grenha Teixeira, J.; Torres, A.; Morais, C. An exploratory study on the emergency remote education experience of higher education students and teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 1357–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Pradas, S.; Hernández-García, A.; Chaparro-Peláez, J.; Prieto, J.L. Emergency remote teaching and students’ academic performance in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, A.; Demircioglu, M.A.; Orazgaliyev, S. COVID-19 and the New Normal of Organizations and Employees: An Overview. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, S.; Schultz, J.; Sellke, K.; Spartz, J. An examination of the flipped classroom approach on college student academic involvement. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High Educ. 2015, 27, 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, E.M.V.; Lai, Y.C. An exploratory study on using wiki to foster student teachers’ learner-centered learning and self and peer assessment. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Innov. Pract. 2012, 11, 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Holzer, J.; Lüftenegger, M.; Korlat, S.; Pelikan, E.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Spiel, K.; Schober, B. Higher Education in times of COVID-19: University students’ basic need satisfaction, self-regulated learning, and well-being. AERA Open 2021, 7, 23328584211003164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanslambrouck, S.; Zhu, C.; Pynoo, B.; Thomas, V.; Lombaerts, K.; Tondeur, J. An in-depth analysis of adult students in blended environments: Do they regulate their learning in an “old school” way? Comput. Educ. 2019, 128, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellinger, J.; Mendenhall, A.; Alemanne, N.D.; Southerland, S.A.; Sampson, V.; Marty, P. Using technology-enhanced inquiry-based instruction to foster the development of elementary students’ views on the nature of science. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2019, 28, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kleij, F.M.; Feskens, R.C.W.; Eggen, T.J.H.M. Effects of feedback in a computer-based learning environment on students’ learning outcomes: A meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2015, 85, 475–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, M.; Sahin, C.; Arcagok, S.; Demir, M.K. The effect of augmented reality applications in the learning process: A meta-analysis study. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2018, 74, 165–186. [Google Scholar]

- Augé, M. Non-Lieux; Editions du Seuil: Paris, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- McLuhan, M. Understanding Media. The Extensions of Man; McGraw-Hill: New York, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, D.; Barton, A.C.; Turner, C.; Hardy, K.; Roper, A.; Williams, C.; Herrenkohl, L.D.; Davis, E.A.; Tasker, T. Community infrastructuring as necessary ingenuity in the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Res. 2020, 49, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parson, D.; Inkila, M.; Lynch, J. Navigating learning worlds: Using digital tools to learn in physical and virtual spaces. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 35, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shihi, H.; Kumar, S.; Sarrab, M. Neural network approach to predict mobile learning acceptance. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2018, 23, 1805–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiq, F.; Scherer, R. Is there a gender gap? A meta-analysis of the gender differences in students’ ICT literacy. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 27, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D. Rhizomatic Education: Community as Curriculum. Innov. J. Online Educ. 2008, 4, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Eschenbrenner, B.; Nah, F. Learning through mobile devices: Leveraging affordances as facilitators of engagement. Int. J. Mob. Learn. Organ. 2019, 13, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristovnik, A.; Keržić, D.; Ravšelj, D.; Tomažević, N.; Umek, L. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Life of Higher Education Students: A Global Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurfaradilla, N.M.; Husnin, H.; Mahmud, S.N.D.; Halim, L. Mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic: A snapshot from Malaysia into the coping strategies for pre-service teachers’ education. J. Educ. Teach. 2020, 46, 546–553. [Google Scholar]

- Espegel, C.; Feliz, S.; Buedo, J.A. Pedagogical Polysoheres. Analytical study of the local cosmologies of the COVID-19. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Educational Innovation in Architecture JIDA’20, Málaga, Spain, 12–13 November 2020; Bardí i Milà, B., García-Escudero, D., Eds.; Uma Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore, K.F.; Angleton, C.; Pruitt, J.; Miller-Crumes, S. Putting a focus on social emotional and embodied learning with the visual learning analysis. Early Child. Educ. J. 2019, 47, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.; Bogdan, R.; DeVault, M. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, B.; Cardon, P.; Poddar, A.; Fontenot, R. Does sample size matter in qualitative research? A review of qualitative interviews in is research. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2013, 54, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, C.; Ballau, M. Reliability and validity in qualitative research. In Social Work: Research and Evaluation. Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches; Grinnell, R.M., Unrau, Y., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 438–449. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A.; Cramer, D. Quantitative Data Analysis for Social Scientists; Routledge: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Broussard, M.; Diakopoulos, N.; Guzman, A.L.; Abebe, R.; Dupagne, M.; Chuan, C.-H. Artificial intelligence and journalism. J. Mass Commun. 2019, 96, 673–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, M.; Early, M.; Chemjor, W. Designing multimodal texts in a girls’ afterschool journalism club in rural Kenya. Lang Educ. 2019, 33, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Santiago, B.; Olivares-Ramírez, J.M.; Rodríguez-Reséndiz, J.; Dector, A.; García-García, R.; González-Durán, J.E.E.; Ferriol-Sánchez, F. Learning Management System-Based Evaluation to Determine Academic Efficiency Performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Han, J.Y.; Liu, C.; Xu, H. How do university students’ perceptions of the instructor’s role influence. Their learning outcomes and satisfaction in cloud-based virtual classrooms during the COVID-19 pandemic? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 627443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutumisu, M.; Chin, D.; Schwartz, D.L. A digital game-based assessment of middle school and college students’ choices to seek critical feedback and to revise. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 50, 2977–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, H.L.; Liu, Y.L.; Chou, C. Privacy behavior profiles of underage facebook users. Comput. Educ. 2019, 128, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Sepulveda, M.V.; Fonseca, D.; García-Holgado, A.; García-Penalvo, F.J.; Franquesa, J.; Redondo, E.; Moreira, F. Evaluation of an interactive educational system in urban knowledge acquisition and representation based on students’ profiles. Expert Syst. 2020, 37, e12570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarian, A.; Pantazis, E.; Carneiro, J.P.; Gerber, D.; Becerik-Gerber, B. Lights, building, action: Impact of default lighting settings on occupant behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montes de Oca, I.; Risco, L. Apuntes de Diseño de Interiores: Principios Básicos de Escalas, Espacios, Colores y Más; Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas: Lima, Perú, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ly, D.P.; Jena, A.B. Sex differences in time spent on household activities and care of children among US physicians, 2003–2016. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 1484–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Sub-Code | ||

| Architectural elements | Interior door | 60 | 100.00 |

| Exterior door | 3 | 5.00 | |

| Window | 60 | 100.00 | |

| Thermal comfort | Radiator | 60 | 100.00 |

| Air conditioning | 7 | 11.67 | |

| Illumination | Window curtain | 25 | 41.67 |

| Window roller blind | 24 | 40.00 | |

| Ceiling lamp | 60 | 100.00 | |

| Floor lamp | 8 | 13.33 | |

| Bedside table lamp | 12 | 20.00 | |

| Adjustable lamp | 49 | 81.67 | |

| Sofas/Beds | Sofa | 6 | 10.00 |

| Sofa-bed | 3 | 5.00 | |

| Bed | 29 | 48.33 | |

| Tables | Desk table | 43 | 71.67 |

| Integrated table and bed | 12 | 20.00 | |

| Table and shelf (study cabinet) | 13 | 21.67 | |

| Adjustable low table | 3 | 5.00 | |

| Dining Table | 2 | 3.33 | |

| Coffee table | 3 | 5.00 | |

| Seating | Chair | 15 | 25.00 |

| Wheelchair | 34 | 56.67 | |

| Ergonomic office chair | 13 | 21.67 | |

| Storage | Bookshelf-library | 33 | 55.00 |

| Shelf | 31 | 51.67 | |

| Living room furniture | 3 | 5.00 | |

| Sideboard-comfortable | 4 | 6.67 | |

| Cabinet | 14 | 23.33 | |

| Wardrobe | 33 | 55.00 | |

| Technological devices | Mobile | 60 | 100.00 |

| Desktop computer | 5 | 8.33 | |

| Laptop | 59 | 98.33 | |

| Display screen (dual screen) | 29 | 48.33 | |

| Tablet | 18 | 30.00 | |

| Printer | 16 | 26.67 | |

| Scanner | 15 | 25.00 | |

| Telephone | 4 | 6.67 | |

| Work accessories | Desktop organizer/Pen holder | 43 | 71.67 |

| Filing cabinet | 20 | 33.33 | |

| Case | 44 | 73.33 | |

| Bookstore (more than 10 books approx.) | 48 | 80.00 | |

| Calendar | 24 | 40.00 | |

| Decorative elements | Wall decoration (photo, painting...) | 51 | 85.00 |

| Plant | 15 | 25.00 | |

| Mirror | 15 | 25.00 | |

| Wall clock (time control) | 3 | 5.00 | |

| Leisure | TV | 7 | 11.67 |

| Stereo | 15 | 25.00 | |

| Musical instrument | 7 | 11.67 | |

| Sports equipment | 11 | 18.33 | |

| Gymnastics equipment (exercise bike, elliptical...) | 4 | 6.67 | |

| Care | Children’s equipment (playground, cot...) | 1 | 1.67 |

| Pet | 6 | 10.00 | |

| Variable 1 | Variable 2 | χ2 | p-Value | Cramér’s V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Space | Tables | 22.34925 | 0.00045 | 0.54228 |

| Sofas and beds | Natural light source | 12.73325 | 0.00525 | 0.46067 |

| Colour | Space | 11.32152 | 0.01011 | 0.43439 |

| Access | Sofas and beds | 7.10983 | 0.02858 | 0.43255 |

| Colour | Tables | 13.57603 | 0.01854 | 0.42265 |

| Colour | Personal care items | 1.21528 | 0.27029 | 0.41667 |

| Area | Personal care items | 1.21528 | 0.27029 | 0.41667 |

| Access | Tables | 13.08293 | 0.02261 | 0.41490 |

| Space | Storage | 20.21256 | 0.00114 | 0.41388 |

| Variable 1 | Variable 2 | χ2 | p-Value | Cramér’s V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | Tables | 11.35117 | 0.04485 | 0.38647 |

| Background | Natural light source | 8.75000 | 0.03281 | 0.38188 |

| Colour | Sofas and beds | 4.20323 | 0.12226 | 0.33258 |

| Access to room | Storage | 11.89883 | 0.03620 | 0.31755 |

| Background | Sofas and beds | 3.78320 | 0.15083 | 0.31553 |

| Access to room | Tables | 5.91830 | 0.11565 | 0.31407 |

| Colour | Access to room | 5.87029 | 0.05312 | 0.31279 |

| Colour | Leisure facilities | 4.13049 | 0.38863 | 0.30639 |

| Access to room | Space | 6.36878 | 0.09498 | 0.30381 |

| Variable | χ2 | p-Value | Cramér’s V |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workspace type | 2.48570 | 0.47788 | 0.20354 |

| Area | 0.63020 | 0.88949 | 0.10249 |

| Screen and physical background colour | 0.36915 | 0.54347 | 0.07844 |

| Screen and physical background object | 1.38296 | 0.50083 | 0.15182 |

| Screen and room access | 2.26272 | 0.32259 | 0.19420 |

| Screen and light access | 3.70335 | 0.29533 | 0.24844 |

| Doors and windows | 1.12513 | 0.56975 | 0.09564 |

| Heating and air conditioning | 1.86942 | 0.17154 | 0.16704 |

| Curtains and blinds | 1.70273 | 0.19193 | 0.18641 |

| Types of lamps | 2.43628 | 0.48692 | 0.13743 |

| Types of sofas and beds | 0.62030 | 0.73334 | 0.12776 |

| Types of tables | 5.24766 | 0.38641 | 0.26277 |

| Types of chairs | 0.59538 | 0.74253 | 0.09799 |

| Storage units | 12.54352 | 0.02805 | 0.32604 |

| ICT devices | 6.50161 | 0.48254 | 0.17765 |

| Desktop items | 1.35840 | 0.85139 | 0.08711 |

| Decorative elements | 4.27119 | 0.23363 | 0.22549 |

| Leisure equipment | 2.22711 | 0.69407 | 0.22498 |

| Children’s equipment and pet | 0.02431 | 0.87611 | 0.05893 |

| Variable | χ2 | p-Value | Cramér’s V |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workspace type | 3.15635 | 0.36814 | 0.22936 |

| Area | 4.78357 | 0.18835 | 0.28236 |

| Screen and physical background colour | 0.61477 | 0.43300 | 0.10122 |

| Screen and physical background object | 3.03671 | 0.21907 | 0.22497 |

| Screen and room access | 7.07163 | 0.02914 | 0.34331 |

| Screen and light access | 0.30701 | 0.95871 | 0.07153 |

| Doors and windows | 3.12541 | 0.20957 | 0.15940 |

| Heating and air conditioning | 0.00174 | 0.96671 | 0.00510 |

| Curtains and blinds | 0.18133 | 0.67023 | 0.06083 |

| Types of lamps | 2.24272 | 0.52358 | 0.13185 |

| Types of sofas and beds | 1.70155 | 0.42708 | 0.21161 |

| Types of tables | 8.47126 | 0.13211 | 0.33386 |

| Types of chairs | 1.29231 | 0.52406 | 0.14437 |

| Storage units | 6.14879 | 0.29201 | 0.22827 |

| ICT devices | 4.99258 | 0.66087 | 0.15568 |

| Desktop items | 3.05387 | 0.54885 | 0.13062 |

| Decorative elements | 1.44968 | 0.69393 | 0.13137 |

| Leisure equipment | 5.85107 | 0.21055 | 0.36466 |

| Children’s equipment and pet | 1.21528 | 0.27029 | 0.41667 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feliz, S.; Ricoy, M.-C.; Buedo, J.-A.; Feliz-Murias, T. Students’ E-Learning Domestic Space in Higher Education in the New Normal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137787

Feliz S, Ricoy M-C, Buedo J-A, Feliz-Murias T. Students’ E-Learning Domestic Space in Higher Education in the New Normal. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):7787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137787

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeliz, Sálvora, María-Carmen Ricoy, Juan-Andrés Buedo, and Tiberio Feliz-Murias. 2022. "Students’ E-Learning Domestic Space in Higher Education in the New Normal" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 7787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137787

APA StyleFeliz, S., Ricoy, M.-C., Buedo, J.-A., & Feliz-Murias, T. (2022). Students’ E-Learning Domestic Space in Higher Education in the New Normal. Sustainability, 14(13), 7787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137787