The Moderator Effect of Communicative Rational Action in the Relationship between Emotional Labor and Job Satisfaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Emotional Labor

2.2. Job Satisfaction

2.3. Communicative Rational Action

- (i).

- To briefly explain, rationalism is based on the principle of individuals acting rationally. An individual uses the mechanism of intelligence in daily practices, relations with other people, business, and family life, short- and long-term plans, and similar conditions. Therefore, the individuals’ mental activities, action motivations and contents, comparing and focusing on target activities are at a developed level. The rationalism process designs the individual’s life from beginning to end. This may be indicated as cost minimization and profit maximization [73].

- (ii).

- Value-rationality may be mentioned if an individual acts in principle or with values. In this phase, the individual acts vis-a-vis a principle or a value rather than the benefits. Value-rationality includes the binding of instruments. These are motivation sources such as beliefs, social responsibility, glory, and loyalty. This type of action takes place in the individual’s mind as a direct aim. Ensuring the ideal benefits is not important. A value should be generally accepted and principled to be rational [74].

- (iii).

- Practical-rational action comes into being by combining the action conditions of purposive-rational action and value-rational action. Practical-rational action requires expressing a rational goal or goals to meet needs. It includes searching and comparing the most appropriate and effective tools, methods, and applications. Additionally, it requires being ready for the realization or failure of the expectations and generating strategies for unexpected conditions. Individuals who carry out practical-rational actions try to realize the benefits, success, and profit. At the same time, they consider the respondents’ rights and increase common welfare. Individuals protect and internalize the environment such as their own homes and try not to cause harm. They also try to increase the sources of the next generations [75].

- (iv).

- Rational communication has some conditions and features. When individuals communicate with each other in business life, first of all, they should not seek only profit. Individuals or actors (individual, firm, institution, government) must first communicate with each other for the purpose of agreement [76]. The parties communicating for the purpose of agreement should know each other. It should be accepted that the other person takes part in this process as a subject. Belief that a compromise can be reached must be entered into. Though the outcome is not certain. It should come together with the intention of being constructive. Common norms that meet the expectations of each actor should be determined. These norms should be known, understood, and accepted by all segments. The discussion should start on an equal footing. Language should be used freely and effectively. Intentions should be presented clearly and precisely. Understandable expressions should be used, be honest, and show a reliable stance. During the completion of the action, inappropriate behaviors such as violence, lies, deception, cheating, and domination should not be resorted to. It should be understood that opposing views are true and valid, and new discussions should be approached with tolerance [77].

- (v).

- Communication between the units of a firm family is generally strategic nowadays so all units are self-possessed. Big problems exist in terms of trust. Acting together is weak. Channels for interdependence and co-operation are mostly closed. All units only consider their own benefits, so they develop various methods to ensure their benefits. However, gaining profit for all units is difficult in this type of relationship [78]. Thus, Habermas indicates that strategic action and communicative rational action must be carried out collaterally. All actors gain when relations in the firm family and with other firms are organized in this way. It is not reasonable to remove strategic action from the firm relations. Firms must develop definite strategies and maintain continuity to reach their goals [79].

2.4. Relationship between the Variables and Literature Review

2.5. The Role of Communicative Rational Action in the Effect of Emotional Labor on Job Satisfaction

3. Materials and Methods

Validity and Reliability Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Basic Statistics

4.2. Correlation Analysis

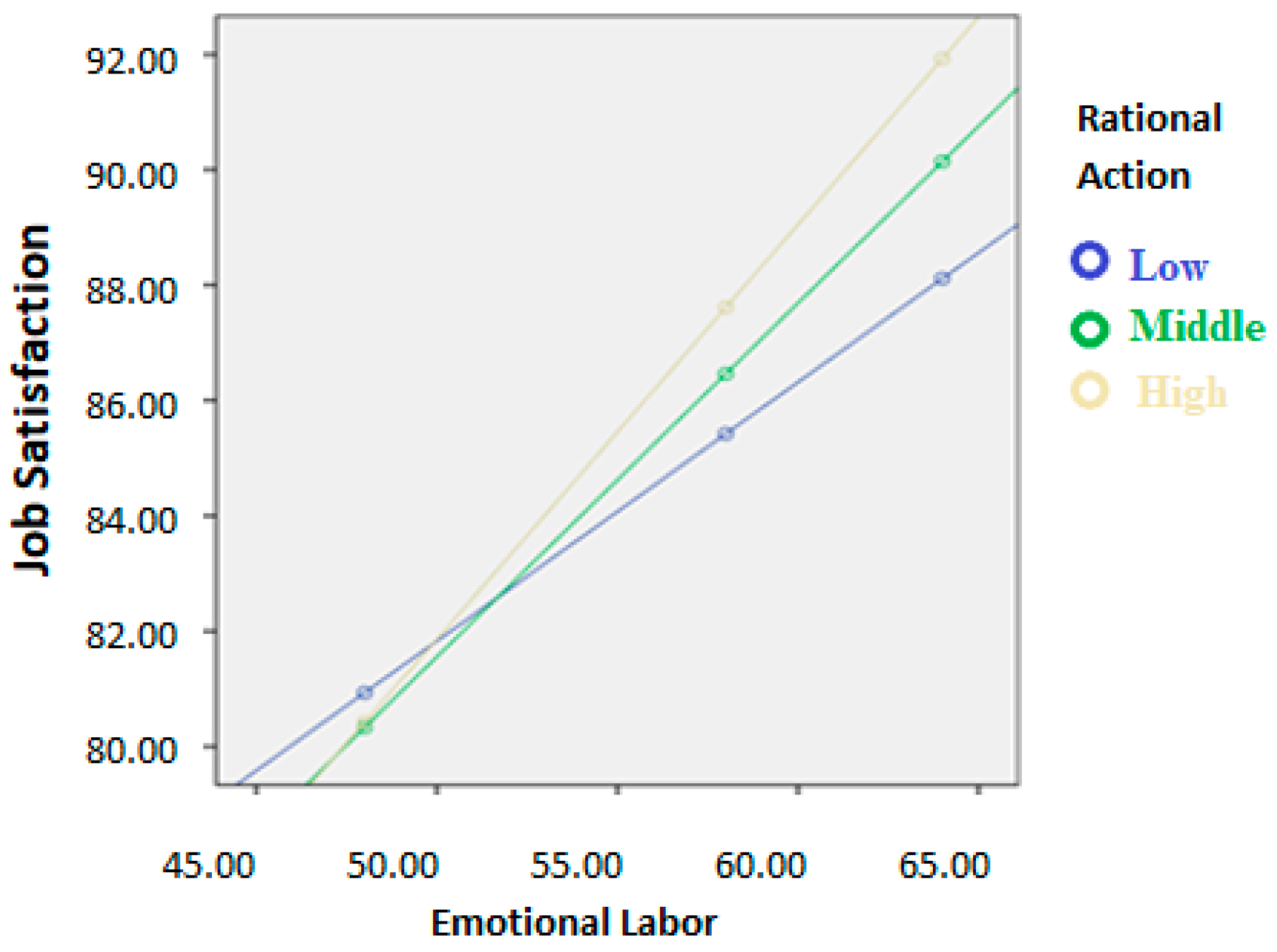

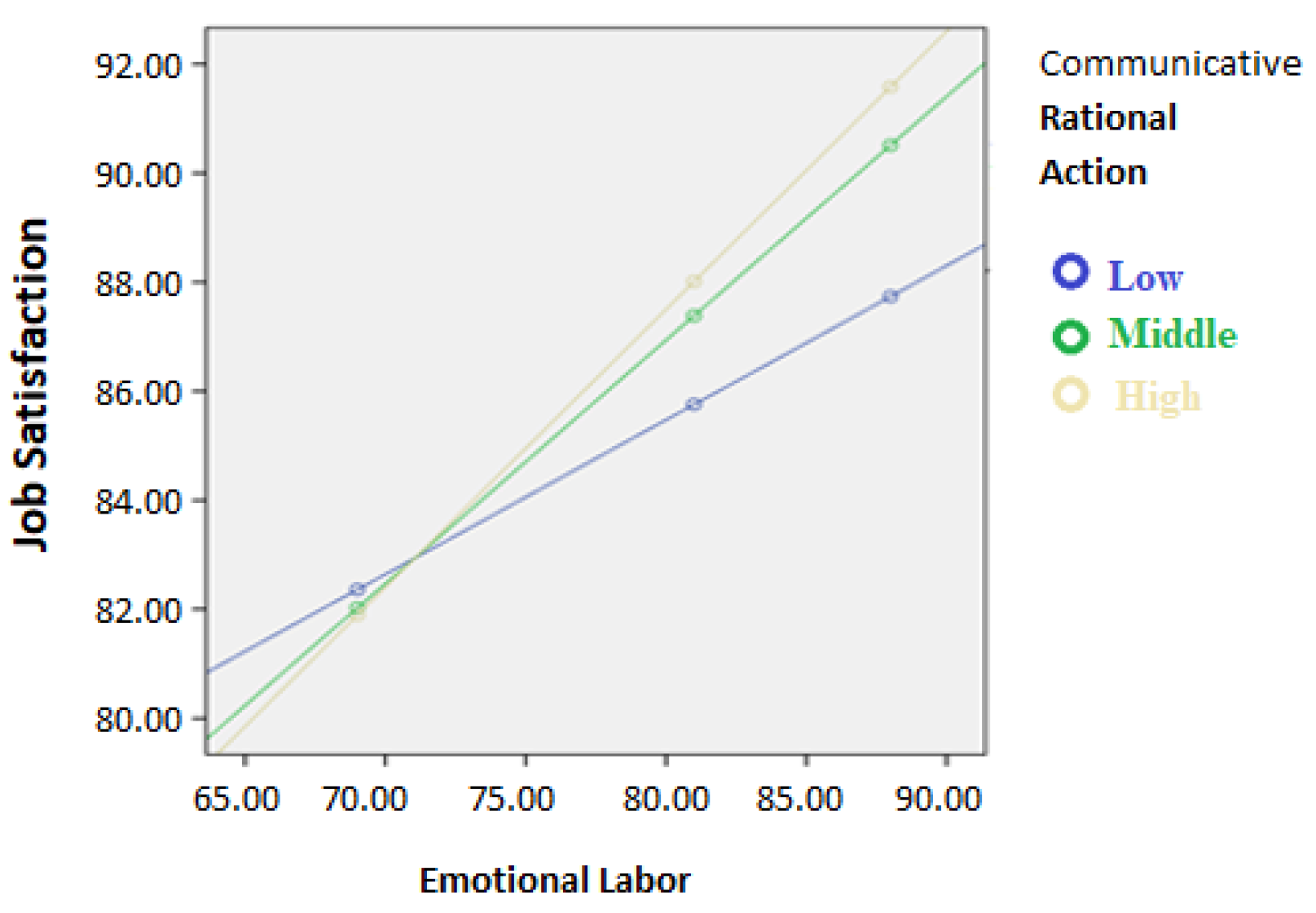

4.3. Moderator Impact Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Factors | Statement No. | Communicative Rational Action Scale Statements | Totally Disagree | Disagree | No Decision | Agree | Totally Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rationality | 1. | I realize that all my decisions are in accordance with a strategy. | |||||

| 2. | I try to determine my decisions and actions considering the principle of maximum profit. | ||||||

| 3. | I use intelligence in all of my decisions and actions. | ||||||

| Value-Rational Action | 4. | I always prefer making the ethically correct choice. | |||||

| 5. | I try to be fair in all of my decisions and actions. | ||||||

| 6. | I give priority to competence in employment, promotion, and rotation. | ||||||

| 7. | I try to be a model for my employees. | ||||||

| Practical-Rational Action | 8. | I reward successful and devoted employees. | |||||

| 9. | I take our firm’s social responsibility policy and principles into consideration in all activities. | ||||||

| 10. | I ensure all employees’ rights are not being infringed upon. | ||||||

| 11. | I do not carry out any unethical actions even though I am sure it will lead to high profits. | ||||||

| 12. | I consider not only the firm’s benefit but also society’s benefit when considering the policies and activities. | ||||||

| Rational Communication | 13. | All employees can communicate with anyone in working hours. | |||||

| 14. | I consult while deciding. | ||||||

| 15. | I listen to employees to make them feel important. | ||||||

| 16. | Employees can easily communicate with me in and out of working hours. | ||||||

| 17. | I talk with sad and depressed employees. | ||||||

| 18. | I realize the employees’ and partner’s beneficial opinions and suggestions. | ||||||

| Firm Family | 19. | I consider employee satisfaction prior to customer satisfaction. | |||||

| 20. | I consider employees as humans first. | ||||||

| 21. | I consider not only the firm’s benefits but also thee employees’ and partner’s benefits. |

References

- Brand, T.; Blok, V.; Verweij, M. Stakeholder Dialogue as Agonistic Deliberation: Exploring the Role of Conflict and Self-Interest in Business-NGO Interaction. Bus. Ethic. Q. 2019, 30, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çamlı, A.Y.; Virlanuta, F.O.; Palamutçuoğlu, B.T.; Bărbuță-Mișu, N.; Güler, Ş.; Züngün, D. A Study on Developing a Communicative Rational Action Scale. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elganas, T.; Sheppard, R. Effects of emotional labor on job satisfaction and customer satisfaction: An empirical study of Lib-yan banks. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2019, 9, 1261–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, L.; Zsigmond, T.; Machová, R. The effects of emotional intelligence and ethics of SME employees on knowledge sharing in Central-European countries. Oeconomia Copernic. 2021, 12, 907–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, S.; Belios, E. Effect of Age on Job Satisfaction and Emotional Exhaustion of Primary School Teachers in Greece. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chehab, O.; Ilkhanizadeh, S.; Bouzari, M. Impacts of Job Standardisation on Restaurant Frontline Employees: Mediating Effect of Emotional Labour. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, R.H.; Humphrey, B.E. Emotional Labor in Service Roles: The Influence of Identity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaza, N.A.; Nowlin, E.L.; Wu, G.J. Staying Engaged on the Job: The Role of Emotional Labor, Job Resources, and Customer Orientation. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 1470–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Humphrey, R. Emotion in the Workplace: A Reappraisal. Hum. Relat. 1995, 48, 97–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, R.H.; Ashforth, B.E.; Diefendorff, J.M. The bright side of emotional labor. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 749–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefendorff, J.M.; Gosserand, R.H. Understanding the Emotional Labor Process: A Control The Oryperspective. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tsang, K.K.; Wang, L.; Liu, D. Emotional Labor Mediates the Relationship between Clan Culture and Teacher Burnout: An Examination on Gender Difference. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.A.; Feldman, D.C. The dimentions, antecedents and consequences of emotional labor. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 986–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, R. Emotional dissonance in organizations: A conceptualization of consequences, mediators and moderators. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 1998, 19, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, D. Emotion work and psychological strain: A review of the literature and some conceptual considerations. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2002, 12, 237–268. [Google Scholar]

- Brotheridge, C.M.; Grandey, A.A. Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives of “people work”. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 60, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A. When “The Show Must Go on”: Surface Acting and Deep Acting as Determinants of Emotional Exhaustion and Peer-Rated Service Delivery. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, W.; Chen, Z. When I put on my service mask: Determinants and outcomes of emotional labor among hotel service providers according to affective event theory. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, A.; Schüpbach, H. Longitudinal effects of emotional labour on emotional exhaustion and dedication of teachers. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, R.E.; Groth, M.; Frenkel, S.J. Relationships Between Emotional Labor, Job Performance, and Turnover. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.-A.M. Service With a Smile: Antecedents and Consequences of Emotional Labor Strategies. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Chen, A. Emotional labor: A comprehensive literature review. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2021, 40, 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A. The Effects of Emotional Labor: Employee Attitudes, Stress and Performance. Ph.D. Thesis, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2000. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Naring, G.; Briet, M.; Brouwers, A. Beyond demand-control: Emotional labor and symptoms of burnout in teachers. Work Stress 2006, 20, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogrebin, M.; Poole, E. Emotion management: A study of police response to tragic events. In Social Perspectives on Emotion; Flaherty, M.G., Ellis, C., Eds.; JAI Press: Stamford, CT, USA, 1995; Volume 3, pp. 149–168. [Google Scholar]

- Heuven, E.; Bakker, B.A. Emotional dissonance and burnout among cabin attendants. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2003, 12, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, D.; Holz, M. On the positive and negative effects of emotion work in organizations. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2006, 15, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, N.; Bhatnagar, D.; Mishra, S.K. Effect of emotional labor on emotional exhaustion and work attitudes among hospi-tality employees in ındia. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2013, 12, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, A.R. The Managed Heart: The Commercialization of Human Feeling; University of California, Berkeley Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Pugliesi, K. The Consequences of Emotional Labor: Effects on Work Stress, Job Satisfaction, and Well-Being. Motiv. Emot. 1999, 23, 125–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelmann, P.K. Emotional labor as a potential source of job stress. In Organizational Risk Factors for Job Stress; Sauter, S.L., Murphy, L.R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 371–381. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J.Y.; Wang, C.H. Emotional labor of the tour leaders: An exploratory study. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glomb, T.M.; Tews, M.J. Emotional labor: A conceptualization and scale development. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.A.; Barnes, C.M. A Multilevel Field Investigation of Emotional Labor, Affect, Work Withdrawal, and Gender. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 116–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, S.; Morgan, L.M. A longitudinal analysis of the association between emotion regulation, job satisfaction, and intentions to quit. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2002, 23, 947–962. [Google Scholar]

- Schaubroeck, J.; Jones, J.R. Antecedents of workplace emotional labor dimensions and moderators of their effects on physical symptoms. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2000, 21, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.; Jang, Y.-H.; Edelson, S.A. The path from role clarity to job satisfaction: Natural acting and the moderating impact of perceived fairness of compensation in services. Serv. Bus. 2021, 15, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; Dorsey, K.D.; Mosley, A.L. Licensed funeral directors: An empirical analysis of the dimensions and consequences of emotional labor. Int. Manag. Rev. 2009, 5, 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J.A.; Feldman, D.C. Managing Emotions in the Workplace. J. Manag. 1997, 9, 257–274. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J.; Han, Y.S. Relationship between emotional labor consequences and employees’ coping strategy. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 14, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Gao, J. Examining Emotional Labor in COVID-19 through the Lens of Self-Efficacy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, F.; Tang, C.S.-K.; Tang, S. Psychological capital as a moderator between emotional labor, burnout, and job satisfaction among school teachers in China. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2011, 18, 348–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su-Bin, J.; Eun-Mi, C.; Jun-Seon, C. The Effects of Emotional Labor on Burnout, Turnover Intention, and Job Satisfaction among Clinical Dental Hygienists. J. Korean Acad. Oral Health 2014, 38, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo, S.J. Mediating Effect of Positive Psychological Capital on the Relationship between Emotional Labor and Job Satisfaction in Clinical Nurses. J. Korea Converg. Soc. 2020, 21, 400–409. [Google Scholar]

- Adil, A.; Kamal, A.; Atta, M. Mediating Role of Emotions at Work in Relation to Display Rule Demands, Emotional Labor, and Job Satisfaction. J. Behav. Sci. 2013, 23, 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, J.; Huang, S.S.; Hou, P. Emotional intelligence, emotional labor, perceived organizational support, and job sat-isfaction: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.-Z.; Chen, H.-F.; Yang, C.-C.; Chow, T.-H.; Hsu, C.-H. The Relationship between Medical Staff’s Emotional Labor, Leisure Coping Strategies, Workplace Spirituality, and Organizational Commitment during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciotto, G.; Pace, F. The Role of Surface Acting in the Relationship between Job Stressors, General Health and Need for Recovery Based on the Frequency of Interactions at Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, D.-J.; Park, J.-H.; Jung, S.-E.; Lee, B.; Kim, M.-S.; Sim, K.-L.; Choi, Y.-H.; Kwon, C.-Y. The Experience of Emotional Labor and Its Related Factors among Nurses in General Hospital Settings in Republic of Korea: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, R.; Cheung, C.; Lugosi, P. The impacts of cultural intelligence and emotional labor on the job satisfaction of luxury hotel employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 100, 103084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J. Relationship between Emotional Labor and Job Satisfaction: Testing Mediating Role of Emotional Intelligence on South Korean Public Service Employees. Public Organ. Rev. 2020, 21, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, I.-A.; Lin, S.-Y.; Chen, Y.-S.; Wu, S.-T. The influences of abusive supervision on job satisfaction and mental health: The path through emotional labor. Pers. Rev. 2021, 51, 823–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Application of the Cognitive Dissonance Theory to the Service Industry. Serv. Mark. Q. 2011, 32, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmana, S.S.; Padmakusumah, R.R.; Nilasari, I.; Handayani, R. Does Job Characteristics Predicted Employee Job Satis-faction? Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. 2021, 12, 1627–1632. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Jiang, Z.; Park, D.S. Emotional labor strategy and job satisfaction: A Chinese perspective. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2013, 41, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. What is job satisfaction? Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1969, 4, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Z.; Mirza, A.M.; Sajid, M.; Adeel, M. Impact of Emotional Labor on Emotional Exhaustion and Job Satisfaction in Public Sector Organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. Macrothink Inst. 2018, 8, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyadi, S. The Influence of Leadership Style, Individual Characteristics and Organisational Climate on Work Motivation, Job Satisfaction and Performance. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 2020, 13, 662–677. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, B.J.; Anwar, G. An Empirical Study of Employees’ Motivation and its Influence Job Satisfaction. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2021, 5, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvey, R.D.; Bouchard, T.J.; Segal, N.L.; Abraham, L.M. Job satisfaction: Environmental and genetic components. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.J.; Dawis, R.V.; England, G.W.; Lofquist, L.H. Manual for The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Minn. Stud. Vocat. Rehabil. 1967, 22, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Novitasari, D.; Asbari, M.; Wijaya, M.R.; Yuwono, T. Effect of Organizational Justice on Organizational Commitment: Mediating Role of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Satisfaction. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Stud. (IJSMS) 2020, 3, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-C.; Yeh, T.-F.; Lai, I.-J.; Yang, C.-C. Job Competency and Intention to Stay among Nursing Assistants: The Mediating Effects of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Job Satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Chen, T.; Schøtt, T.; Gu, F. Entrepreneurs’ Life Satisfaction Built on Satisfaction with Job and Work–Family Balance: Embedded in Society in China, Finland, and Sweden. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rožman, M.; Peša, A.; Rajko, M.; Štrukelj, T. Building Organisational Sustainability during the COVID-19 Pandemic with an Inspiring Work Environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, F.; Zappalà, S. Social Isolation and Stress as Predictors of Productivity Perception and Remote Work Satisfaction during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Concern about the Virus in a Moderated Double Mediation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A.; Topino, E.; Di Fabio, A. The protective role of life satisfaction, coping strategies and defense mechanisms on perceived stress due to COVID-19 emergency: A chained mediation model. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erro-Garcés, A.; Urien, B.; Čyras, G.; Janušauskienė, V.M. Telework in Baltic Countries during the Pandemic: Effects on Wellbeing, Job Satisfaction, and Work-Life Balance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.; Hong, W. The Effect of Food Sustainability and the Food Safety Climate on the Job Stress, Job Satisfaction and Job Commitment of Kitchen Staff. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, T.; Jawaad, M.; Butt, I. The Influence of Person–Job Fit, Work–Life Balance, and Work Conditions on Organizational Commitment: Investigating the Mediation of Job Satisfaction in the Private Sector of the Emerging Market. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berber, N.; Gašić, D.; Katić, I.; Borocki, J. The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction in the Relationship between FWAs and Turnover Intentions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, H. Rationality and Capitalism in Max Weber’s Analysis of Western Modernity. J. Class. Sociol. 2002, 2, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wirth, L.; Parsons, T. The structure of social action: A study in social theory with special reference to a group of recent euro-pean writers. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1939, 4, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Weber, M. Economy and Society; Roth, G., Wittich, C., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkely, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, A. Habermas on rationality: Means, ends and communication. Eur. J. Political Theory 2022, 21, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Essen, M.; Strike, V.M.; Carney, M.; Sapp, S.G. The Resilient Family Firm: Stakeholder Outcomes and Institutional Effects. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2015, 23, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. The Theory of Social and Economic Organization; Henderson, A.M., Parsons, T., Eds.; William Hodge and Company Press: London, UK, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Kalberg, S. Max Weber’s Types of Rationality: Cornerstones for the Analysis of Rationalization Processes in History. Am. J. Soc. 1980, 85, 1145–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Madera, J.M. A systematic literature review of emotional labor research from the hospitality and tourism literature. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2808–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A.; Sayre, G.M. Emotional labor: Regulating emotions for a wage. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 28, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, M.L. Psychological Net Worth: Finding the Balance between Psychological Capital and Psychological Debt. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nenbraska, Lincoln, NE, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.; Gao, J.; Chen, C.; Mu, D. How Does Emotional Labor Impact Employees’ Perceptions of Well-Being? Examining the Mediating Role of Emotional Disorder. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M. Employee–Organization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Ok, C.; Hwang, J. An emotional labor perspective on the relationship between customer orientation and job satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 54, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, H.Y.; Hecker, R.; Martin, A. Predicting nurses’ well-being from job demands and resources: A cross-sectional study of emotional labour. J. Nurs. Manag. 2012, 20, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, J.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Cao, J.; Jia, Z. The effects of emotional labor and competency on job satisfaction in nurses of China: A nationwide cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2018, 5, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsola, K.O.; Fontaine, R.A.H.; Jan, M.T. Impact of surface acting and deep acting techniques on teachers’ organizational commitment. PSU Res. Rev. 2020, 4, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, K.; Li, Y.; Jabeen, F.; Khan, A.N.; Chen, S.; Khalid, G.K. Influence of female managers’ emotional display on frontline employees’ job satisfaction: A cross-level investigation in an emerging economy. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 1491–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Ok, C. Reducing burnout and enhancing job satisfaction: Critical role of hotel employees’ emotional intelligence and emotional labour. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.-H.; Chang, C.-C. Emotional labour, job satisfaction and organizational commitment amongst clinical nurses: A questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torland, M. Emotional labour and job satisfaction of adventure tour leaders: Does gender matter? Ann. Leis. Res. 2011, 14, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouquereau, E.; Morin, A.J.S.; Lapointe, É.; Mokounkolo, R.; Gillet, N. Emotional labour profiles: Associations with key predictors and outcomes. Work Stress 2018, 33, 268–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, H.; Lam, W.; Hu, Q.; Huo, Y.; Zhong, J.A. Chinese hotel employees in the smiling masks: Roles of job satisfaction, burnout, and supervisory support in relationships between emotional labor and performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 826–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M.; Han, S.-J.; Yoo, J.-J.; Moon, T.W. The moderating role of perceived organizational support on the relationship between emotional labor and job-related outcomes. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 605–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Chelladurai, P. Emotional intelligence, emotional labor, coach burnout, job satisfaction, and turnover intention in sport leadership. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2017, 18, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotheridge, C.M.; Lee, R.T. Development and validation of the Emotional Labour Scale. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2003, 76, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulsen, M.; Ozmen, D. The relationship between emotional labour and job satisfaction in nursing. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2020, 67, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisaniello, S.L.; Winefield, H.R.; Delfabbro, P.H. The influence of emotional labour and emotional work on the occupational health and wellbeing of South Australian hospital nurses. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, S.-C.J.; Chen, S.-H.S.; Yuan, K.-S.; Chou, W.; Wan, T.T.H. Emotional Labor in Health Care: The Moderating Roles of Personality and the Mediating Role of Sleep on Job Performance and Satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 574898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choy, M.W.; Kamoche, K. Identifying stabilizing and destabilizing factors of job change: A qualitative study of employee retention in the Hong Kong travel agency industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1375–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, B. Karşılaştırılmalı Bir Çalışma: İbn-i Haldun un Asabiyesi ve Habermas ın Hayat-Evreni. J. Ibn Haldun Stud. Ibn Haldun Univ. 2021, 6, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelzalts, J.E.; Hairston, I.S.; Levy, S.; Orkaby, N.; Krissi, H.; Peled, Y. COVID-19 related worry moderates the association between postpartum depression and mother-infant bonding. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 149, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randazza, M.P.; McKay, D.; Bakhshaie, J.; Storch, E.A.; Zvolensky, M.J. Unhealthy alcohol use associated with obsessive-compulsive symptoms: The moderating effects of anxiety and depression. J. Obs.-Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2022, 32, 100713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miocevic, D.; Arslanagic-Kalajdzic, M.; Kadic-Maglajlic, S. Competition from informal firms and product innovation in EU candidate countries: A bounded rationality approach. Technovation 2021, 110, 102365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, C.M.; Bröring, S.; Lagerkvist, C.-J. Information, attitudes, and consumer evaluations of cultivated meat. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 92, 104226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünler Öz, E. Effect of Emotional Labor On Employees’ Work Outcomes. Ph.D. Thesis, Marmara Universitesi, Istanbul, Turkey, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brotheridge, C.; Lee, R. On the dimensionality of emotional labor Development and validation of an emotional labor scale. In Proceedings of the First Conference on Emotions in Organizational Life, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–8 August 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Baycan, F.A. An Analysis of the Several Aspects of Job Satisfaction between Different Occupational Groups. Ph.D. Thesis, Boğaziçi University, Bebek, Turkey, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Jang, K.S. Nurses’ emotions, emotional labor, and job satisfaction. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2020, 13, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; McVea, J. A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Northcraft, G.B.; Mitroff, I.I. Stakeholders of the Organizational Mind: Toward a New View of Organizational Policy Making. Adm. Sci. Q. 1985, 30, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, S.V.; Pérez-Chiqués, E.; Meza, O.; González, S.A.C. Managerial Challenges of Emotional Labor Disruption: The COVID-19 Crisis in Mexico. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, A.R.; Ahrizal, G.R.; Al Faruq, T. Habermasian reflections on the pandemic and transformational leadership. In Social and Political Issues on Sustainable Development in the Post COVID-19 Crisis; Sukmana, O., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 107–113. [Google Scholar]

| Region of the Participants | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants from three major cities (İstanbul, İzmir, Ankara) | Participants from other cities | ||||||

| 268 (67.34%) | 130 (32.66%) | ||||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | Male | ||||||

| 127 (31.91%) | 271 (68.09%) | ||||||

| Among participants from three major cities (İstanbul, İzmir, Ankara) | Among participants from other cities | ||||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | ||||

| 94 (35.07%) | 174 (64.93%) | 33 (25.38%) | 97 (74.62%) | ||||

| Age Groups | |||||||

| 25–40 Age Group | 41+ Age Group | ||||||

| 263 (61.45%) | 135 (33.92%) | ||||||

| 25–40 Age Group | 41+ Age Group | ||||||

| Among participants from three major cities | Among participants from other cities | Among participants from three major cities | Among participants from other cities | ||||

| 173 (65.78%) | 90 (34.22%) | 95 (57.58%) | 40 (42.42%) | ||||

| 25–40 Age Group | 41+ Age Group | ||||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | ||||

| 84 (31.94%) | 179 (68.06%) | 43 (31.85%) | 92 (68.15%) | ||||

| 25–40 Age Group | 41+ Age Group | ||||||

| Among participants from three major cities | Among participants from other cities | Among participants from three major cities | Among participants from other cities | ||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male |

| 62 (35.84%) | 111 (64.16%) | 22 (24.44%) | 68 (75.56%) | 32 (33.68%) | 63 (66.32%) | 11 (27.50%) | 29 (72.50%) |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | Cut Off Points | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | |||||||

| Emotional Labor | 60 | 94 | 78.4239 | 8.7576 | −0.09 | −1.537 | 0–74 | 75–83 | 84–95 |

| Job Satisfaction | 74 | 95 | 85.829 | 5.80685 | 0.252 | −1.375 | 0–81 | 82–88 | 89–95 |

| Rational Action | 8 | 15 | 13.4801 | 1.78187 | −0.949 | 0.063 | 0–11 | 12–14 | 15 |

| Practical-Rational Action | 17 | 25 | 23.0117 | 2.23551 | −0.908 | −0.215 | 0–22 | 23 | 24–25 |

| Value-Rational Action | 11 | 20 | 18.3817 | 1.49552 | −1.162 | 1.697 | 0–10 | 11–18 | 19–20 |

| Rational Communication | 19 | 30 | 27.0445 | 3.21168 | −0.738 | −0.899 | 0–22 | 23–26 | 27–30 |

| Firm family | 10 | 15 | 13.9087 | 1.35958 | −1.151 | 0.468 | 0–11 | 12–14 | 15 |

| EL | JS | RA | PRA | VRA | RC | FF | CRA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EL | 1.000 | 0.596 ** | 0.011 | −0.127 ** | 0.099 * | −0.224 ** | −0.123 * | −0.130 ** |

| JS | 0.596 ** | 1.000 | 0.132 ** | 0.007 | 0.108 * | 0.046 | −0.077 | 0.059 |

| RA | 0.011 | 0.132 ** | 1.000 | 0.471 ** | 0.490 ** | 0.566 ** | 0.415 ** | 0.772 ** |

| PRA | −0.127 ** | 0.007 | 0.471 ** | 1.000 | 0.395 ** | 0.619 ** | 0.518 ** | 0.825 ** |

| VRA | 0.099 * | 0.108 * | 0.490 ** | 0.395 ** | 1.000 | 0.228 ** | 0.347 ** | 0.578 ** |

| RC | −0.224 ** | 0.046 | 0.566 ** | 0.619 ** | 0.228 ** | 1.000 | 0.416 ** | 0.845 ** |

| FF | −0.123 * | −0.077 | 0.415 ** | 0.518 ** | 0.347 ** | 0.416 ** | 1.000 | 0.664 ** |

| Variable\Model | Model 0 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Control variables | ||||||

| Constant | 50.429 ** | 76.608 ** | 62.959 ** | 62.863 ** | 84.456 ** | 41.115 ** |

| Gender | −6.754 ** | −6.240 ** | −6.447 ** | −6.547 ** | −6.066 ** | −6.615 ** |

| Age | 0.353 | 0.183 | 0.076 | 0.116 | −0.024 | 0.128 |

| Education | 0.016 | −0.016 | 0.089 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.031 |

| Step 2: Main Effects | ||||||

| Emotional labor | 0.527 ** | 0.347 ** | 0.528 ** | 0.545 ** | 0.220 * | 0.895 ** |

| Rational action | 0.057 | −6.240 ** | −0.021 | 0.008 | −0.023 | 0.019 |

| Practical-rational action | −0.032 | −0.088 | −3.378 ** | −0.077 | −0.048 | −0.088 |

| Value-rational action | −0.002 | −0.037 | −0.013 | −2.244 | −0.058 | 0.060 |

| Rational communication | 0.130 | 0.070 | 0.157 | 0.134 | −8.806 ** | 0.138 |

| Firm family | −0.088 | −0.248 | −0.169 | −0.150 | −0.202 | 4.722 |

| Step 3: Two-way Interactions | ||||||

| Emotional labor X Rational action | 0.126 ** | |||||

| Emotional labor X Practical-rational action | 0.059 * | |||||

| Emotional labor X Value-rational action | 0.044 | |||||

| Emotional labor X Rational communication | 0.172 ** | |||||

| Emotional labor X Firm family | −0.087 | |||||

| R2 | 0.630 | 0.653 | 0.647 | 0.643 | 0.664 | 0.645 |

| F | 73.386 | 78.452 | 76.073 | 75.125 | 82.375 | 75.416 |

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| N | 427 | 427 | 427 | 427 | 427 | 427 |

| RE | Effect | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 0.4489 | 0.0843 | 5.3249 | 0.0000 | 0.2832 | 0.6147 |

| Medium | 0.6132 | 0.0412 | 14.8878 | 0.0000 | 0.5323 | 0.6942 |

| High | 0.7192 | 0.0367 | 19.6068 | 0.0000 | 0.6471 | 0.7913 |

| RE | Effect | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 0.5954 | 0.0447 | 13.3076 | 0.0000 | 0.5074 | 0.6833 |

| Medium | 0.5582 | 0.1017 | 5.4895 | 0.0000 | 0.3583 | 0.7580 |

| High | 0.7079 | 0.0342 | 20.7044 | 0.0000 | 0.6407 | 0.7751 |

| RE | Effect | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 0.2736 | 0.0687 | 3.9852 | 0.0000 | 0.1386 | 0.4085 |

| Medium | 0.6326 | 0 0547 | 11.5759 | 0.0000 | 0.5252 | 0.7401 |

| High | 0.7006 | 0.0310 | 22.5844 | 0.0000 | 0.6396 | 0.7616 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Çamlı, A.Y.; Palamutçuoğlu, T.B.; Bărbuță-Mișu, N.; Çavuşoğlu, S.; Virlanuta, F.O.; Alkan, Y.; David, S.; Manea, L.D. The Moderator Effect of Communicative Rational Action in the Relationship between Emotional Labor and Job Satisfaction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7625. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137625

Çamlı AY, Palamutçuoğlu TB, Bărbuță-Mișu N, Çavuşoğlu S, Virlanuta FO, Alkan Y, David S, Manea LD. The Moderator Effect of Communicative Rational Action in the Relationship between Emotional Labor and Job Satisfaction. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):7625. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137625

Chicago/Turabian StyleÇamlı, Ahmet Yavuz, Türker B. Palamutçuoğlu, Nicoleta Bărbuță-Mișu, Selin Çavuşoğlu, Florina Oana Virlanuta, Yaşar Alkan, Sofia David, and Ludmila Daniela Manea. 2022. "The Moderator Effect of Communicative Rational Action in the Relationship between Emotional Labor and Job Satisfaction" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 7625. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137625

APA StyleÇamlı, A. Y., Palamutçuoğlu, T. B., Bărbuță-Mișu, N., Çavuşoğlu, S., Virlanuta, F. O., Alkan, Y., David, S., & Manea, L. D. (2022). The Moderator Effect of Communicative Rational Action in the Relationship between Emotional Labor and Job Satisfaction. Sustainability, 14(13), 7625. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137625