Abstract

The recent years have witnessed striking global demographic shifts. Retired elderly people often stay home, seldom communicate with their grandchildren, and fail to acquire new knowledge or pass on their experiences. In this study, digital technologies based on virtual reality (VR) with tangible user interfaces (TUIs) were introduced into the design of a novel interactive system for intergenerational learning, aimed at promoting the elderly people’s interactions with younger generations. Initially, the literature was reviewed and experts were interviewed to derive the relevant design principles. The system was constructed accordingly using gesture detection, sound sensing, and VR techniques, and was used to play animation games that simulated traditional puppetry. The system was evaluated statistically by SPSS and AMOS according to the scales of global perceptions of intergenerational communication and the elderly’s attitude via questionnaire surveys, as well as interviews with participants who had experienced the system. Based on the evaluation results and some discussions on the participants’ comments, the following conclusions about the system effectiveness were drawn: (1) intergenerational learning activities based on digital technology can attract younger generations; (2) selecting game topics familiar to the elderly in the learning process encourages them to experience technology; and (3) both generations are more likely to understand each other as a result of joint learning.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), people aged 65 or above are considered elderly. A country with the percentage of its population aged 65 and over rising to 7% is called an “aging society”, and when the percentage reaches 14% and 20%, it will then be considered as an “aged society” and a “super-aged society”, respectively [1]. Based on the governmental statistics of 2014, the number of people aged over 65 in Taiwan reached 1.49 million in 1993. This number accounted for more than 7% of the total population then, making Taiwan an aging society, as defined by the WHO. In addition, a 2018 report published by the government revealed that the elderly accounted for 14.1% of Taiwan’s total population then, making the country an “aged society”. This figure is projected to reach 20.6% by 2026, meaning that Taiwan will become a “super-aged society” at that time. Furthermore, in recent years Taiwan has been affected by a declining fertility rate, leading to even faster demographic shifts. Similar situations can be found in a great number of other countries in the world. With the advent of the aging population in these countries, it has become a constant global issue to explore methods that can help educate the elderly.

Another issue in aging societies is the serious inadequacy of intergeneration interactions. In countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Sweden, the elderly and young people tend to have fewer interactions and varying opinions [2] due to their different growth backgrounds and inadequate contacts. In addition, the young people in today’s societies tend to stereotype the elderly. For instance, Hall and Batey [3] revealed that most children think ill of the elderly due to the latter’s declining physical function.

In response to the increasing number of senior citizens, many developed countries and international organizations have begun to formulate policies that emphasize the great importance of education for the elderly. Many countries have put forward learning methods to promote lifelong learning for the elderly, among which intergenerational learning is considered one of the best ways to bridge the generational gap. Ames and Youatt [4] believed that in the face of a larger number of older adults, the age gap has a greater impact on the older and younger generations. Hence, intergenerational programs have been found to be an effective method in providing education and service planning. Kaplan [5] also mentioned that intergenerational learning should be designed to use the advantages of one generation to meet the needs of the other to achieve meaningful and sustained resource exchange and learning between the two generations. Furthermore, Souza and Grundy [6] found that employing intergenerational interactions allowed the elderly to be more confident and positive, and so improved their self-value and happiness. Based on the perspective of the young, it was assumed that young people should be given effective channels to better exchange and cooperate with the elderly [7].

1.2. Research Motivation and Issues

In recent years, in many conventional learning activities, digital technologies have been introduced as auxiliary tools, among which virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) have been widely used. In particular, Ainge [8] suggested that students who have used VR are better at recognizing geometric shapes than those who have not, and that students in general had a positive attitude toward a VR-based learning environment. Virvou and Katsionis [9] also found that VR educational games could effectively arouse students’ interest in learning and had better effects on education than other types of educational software. Meanwhile, with the developments in science and technology, VR has also been particularly adopted to help educate the elderly. For instance, MyndVR [10], a company that integrates VR with elderly health care, is assisting the elderly with diseases such as Alzheimer’s and dementia by enabling them to create and experience a fulfilling and meaningful life in their later years. According to many participants, their aging diseases were relieved, and their physical health was improved. Dennis Lally, the cofounder of Rendever [11], developed a VR-based memory therapy system that brings back fond memories virtually and recreates meaningful scenes or places that older adults want to visit. Benoit et al. [12] combined VR and memory therapy by presenting scenes familiar to participants in a virtual environment with image rendering. Moreover, Manera et al. [13] argued that VR allowed patients with cognitive impairment and dementia to have more fun when performing tasks.

Ultimately, technology-based intergenerational activities can arouse more interest among the younger generations than conventional ones [14,15]. Cases related to conventional intergenerational activities indicated that due to familiarity, the elderly are more likely to have a sense of achievement in conventional activities, such as woodchopping, farming, and cooking [16]. However, only a few intergenerational activities feature combinations of technology and conventional activities, notwithstanding those based on VR and TUIs. In this study, TUIs and VR were integrated into conventional intergenerational activities to make the connections between both generations more interactive and recreational. Under the above premises, the following questions were put forward in this study. (1) Does the application of VR and TUIs to intergenerational learning facilitate emotion exchange and experience-sharing between the two generations? (2) What are the steps in setting up a VR-based system for interactive intergenerational learning for different learning tasks?

1.3. Literature Review

The literature on the elderly’s physical and mental health, intergenerational learning, VR, and TUI design is reviewed in this section.

1.3.1. Physical and Mental Health of the Elderly

According to a report by the European Union, more than half of the world’s population will comprise 48-year-olds or above by 2060, indicating that aging will keep accelerating in the next few decades [17]. Meanwhile, Taiwan has an aging population and a declining birth rate, giving the older and younger generations fewer opportunities to interact than they did in the past. Many studies showed that college students generally had a slightly negative view of the elderly, especially concerning the latter’s physical and mental health [18,19,20]. However, it is worth noting that the two generations have fewer interactions. As the elderly age with time, they continue to suffer from physical and mental functional decline and become subject to increasing pain, discomfort, and inconvenience in life, giving rise to psychological changes. Furthermore, aging can be both physiological and psychological. In terms of physiology, Zajicek [21] held that the elderly could not see clearly and would easily become tired due to vision and memory degeneration. In addition, they easily forget how to operate a computer. With respect to their psychological conditions, the elderly are more likely to feel depressed in hard times, such as when they lose family members, friends, social roles, and physical functions. Thus, according to Shibata and Wada [22], some recreational activities may be adopted as an option when communicating with the elderly. Chatman [23] also found that some of the elderly in a community were so afraid of being sent to nursing institutions after retirement that they did not want to share their health conditions with others, even pretending to look healthy.

Research on the aging of seniors revealed that despite physical and mental changes of the elderly people, an aging society is blessed with a remarkable advantage—abundant older human resources. The most valuable thing that the elderly have lies in their wealth of work and life experiences, considering they lived through diverse situations. If older people can participate in more meaningful activities, their experiences can be shared with younger people to promote social progress. Moreover, their physical and mental health will be improved, reducing medical expenditures.

1.3.2. Intergenerational Learning

Intergenerational learning programs were implemented in 1963 when the P.K. Yonge Developmental Research School in the United States developed the “Adopt a Grandparent Program”. Thereafter, many colleges and universities have begun studying and implementing intergenerational learning programs. In response to generational estrangement caused by population aging, intergenerational learning, which refers to the establishment of mutual learning between the older and younger generations, has emerged globally [5]. Intergenerational learning has been regarded as an informal activity passed down from one generation to another for centuries—a culture bridging tradition and modernization [24]. In modern times, influenced by an increasingly complex society, intergenerational learning is no longer limited to the family, but its influence extends to society and improves the overall social value [25].

Ames and Youatt [4] proposed a comprehensive selection model for intergenerational learning and service activities in classifying conventional intergenerational learning, which can help planners design more diverse and richer learning activities. The model can be divided into three parts: the middle generation, program categories, and selection criteria. In addition, Ohsako [26] divided intergenerational learning into four models/profiles: (1) older adults serving/mentoring/tutoring children and the youth; (2) children and the youth serving/teaching older adults; (3) children, the youth, and older adults serving the community/learning together for a shared task; and (4) children, the youth, and older adults engaged in informal leisure/unintentional learning activities.

Over the past few years, the degree of interaction has been considered a classification criterion. Kaplan [5] thought that this criterion could more effectively explain the positive or negative results of intergenerational learning, and classified intergenerational programs and activities accordingly into the following seven different levels of intergenerational engagement, ranging from initiatives (point #1 of the below) to those that promote intensive contact and ongoing opportunities for intimacy (point #7 of the below): (1) learning about other age groups; (2) seeing the other age group but at a distance; (3) meeting each other; (4) annual or periodic activities; (5) demonstration projects; (6) ongoing intergenerational programs; and (7) ongoing, natural intergenerational sharing, support, and communication. Ames and Youatt [4] put forward the most comprehensive selection model of intergenerational learning and service activities, while Ohsako [26], from a different perspective, enabled planners to design diverse and interesting activities. On the other hand, Kaplan [5] used the interaction degree as a classification criterion, and discussed how interactive methods are generated and how deep and sustainable interactions are conducted based on commonality.

Furthermore, Ames and Youatt [4] found that conventional intergenerational learning activities were mostly service-oriented. Thus, the value and significance of activities to participants must be taken into account when selecting and evaluating the topics involved in the intergenerational activities. A good intergenerational program should not only meet the expected goals, but also provide balanced and diverse activities to participants. Moreover, it is important to introduce digital technology to make intergenerational activities more interactive and recreational for the two generations.

Finally, it is worth noticing that some scholars have investigated the applications of group learning or education from wider points of view. For example, Kyrpychenko et al. [27] studied the structure of communicative competence and its formation while teaching a foreign language to higher education students. The results of the questionnaire survey of the students’ responses provided grounds for the development of experimental methods for such competence formations by future studies. Kuzminykh et al. [28] investigated the development of competence in teaching professional discourse in educational establishments, and showed that the best approach was to adopt a model consisting of two stages based on self-education and group education. The research results revealed that communicative competence may be achieved through a number of activities that may be grouped under four generic categories. Singh et al. [29] proposed an intelligent tutoring system named “Seis Tutor”, that can offer a learning environment for face-to-face tutoring. The performance of the system was evaluated in terms of personalization and adaptation through a comparison with some existing tutoring systems, leading to a conclusion that 73.55% of learners were strongly satisfied with artificial intelligence features. To improve early childhood education for social sustainability in the future, Oropilla and Odegaard [30] suggested the inclusion of intentional intergenerational programs in kindergartens, and presented a framework that featured conflicts and opportunities within overlapping and congruent spaces to understand conditions for various intergenerational practices and activities in different places, and to promote intergenerational dialogues, collaborations, and shared knowledge.

1.3.3. Virtual Reality

The concept of virtual reality (VR) was first proposed in 1950, but was not materialized until 1957. Heilig [31] developed Sensorama, the first VR-based system with sight, hearing, touch, and smell senses, as well as 3D images. In 1985, Lanier [32] expressed that VR must be generated on a computer with a graphics system and various connecting devices in order to provide immersive interactive experiences. Burdea [33] proposed the concept of the 3I VR pyramid, and maintained that VR should have three elements: immersion, imagination, and interaction. Currently, VR can be classified into six categories according to design technology and user interfaces: (1) desktop VR; (2) immersion VR; (3) projection VR; (4) simulator VR; (5) telepresence VR; and (6) network VR; therefore, in recent years, many experts and scholars assumed that the VR technology can improve participants’ attitude toward and interest in learning, and that the interactions in learning tasks can be strengthened in an immersive environment to improve learning effects [9,34].

Many applications have been developed using VR technology in the past. A specific direction of VR applications for human welfare is the use of VR in the healthcare domain. In this research direction, Nasralla [35] studied the construction of sustainable patient-rehabilitation systems with IoT sensors for the development of virtual smart cities. The research results showed that the proposed approach could be useful in achieving sustainable rehabilitation services. In addition, Sobnath et al. [36] advocated the use of AI, big data, high-bandwidth networks, and multiple devices in a smart city to improve the life of visually impaired persons (VIPs) by providing them with more independence and safety. Specifically, the uses of strong ICT infrastructure with VR/AR and various wearable devices can provide VIPs with a better quality of life.

Table 1 summarizes the following key points in this study, based on relevant cases and the literature integrating both VR and the elderly: (1) VR is proven effective and has a positive effect on improving the body and cognition of the elderly; (2) VR-based learning activities can effectively enhance the learners’ interest and help them make more progress; and (3) older people can adapt to VR, which can stimulate their memory according to their familiarity with a given scene, thereby achieving the effect of memory therapy [12]. As Davis mentioned regarding the technology-acceptance model (TAM) model [37,38,39], users’ acceptance of science and technology is affected by “external factors”, such as their living environment, learning style, and personal characteristics. Thus, it is impossible to determine whether the above method can have the same effect on the elderly in a specific society or country. In order to determine the usefulness and acceptability of VR for older Taiwanese people, Syed Abdul et al. [40] invited 30 older people over 60 years old in Taiwan to experience nine different VR games within six weeks, with each experience lasting 15 min. Then, they analyzed the users’ performances with a scale based on the TAM model by Davis. The results showed that the elderly enjoyed the experience, finding VR useful and easy to use, which indicated that the elderly held a positive attitude toward the new technology.

Table 1.

Relevant cases in which VR was used for the elderly.

1.3.4. Tangible User Interfaces

The use of tangible user interfaces (TUIs) is a brand-new user-interfacing concept proposed by Ishii and Ullmer [42]. Unlike graphical user interfaces (GUIs), TUIs emphasize using common objects in daily life as the control interface, making the control action beyond screen manipulations. They allow users to operate the interface more intuitively by moving, grabbing, flipping, and knocking, and in other ways that people think are feasible to control the human–computer interface. Furthermore, TUIs grant a tangible form to utilize digital information or run programs [43].

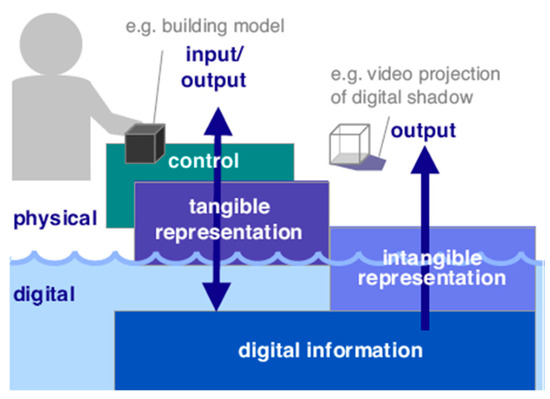

More specifically, TUIs enable digital information to show in a tangible form. A digital interface consists of two important components: input and output, also known as control and representation. Control refers to how users manipulate information, while representation refers to how information is perceived. The tangible form shown in the use of TUIs may be regarded as the digital equivalent to control and representation, and the tangible artifacts operated in applying TUIs may be considered as devices for displaying representation and control. In other words, TUIs combine tangible representation (e.g., objects that can be operated by hand) with digital representation (e.g., images or sounds), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework of TUIs.

The concept of TUIs has been constantly discussed in man–machine interfacing seminars, and has been applied in various fields such as education and learning [44,45,46], music and entertainment [47,48,49], and professional solutions [50,51,52]. From the environmental psychology perspective, psychologists believed that TUIs had a tangible form and took advantage of the “affordance” of objects [53]. Some scholars, who employed the perceptual-motor theory as their research core, focused on user actions generated between them and TUIs, as well as on the dynamic presentation of TUIs [54,55,56,57].

Furthermore, TUIs provide a simpler and more intuitive way to help users accomplish goals. By combining physical manipulations with convenient digital technology, a TUI serves as a bridge connecting users and digital content. Moreover, TUIs have expanded the concept of interface design. Thus, scholars have conducted several discussions of the theoretical basis and scope of the conceptual framework of TUIs. In this study, it is proposed to apply TUIs in intergenerational learning activities, enabling users to intuitively operate interfaces and conduct their distinctive ways of presentation.

1.4. Brief Description of the Proposed Research and Paper Organization

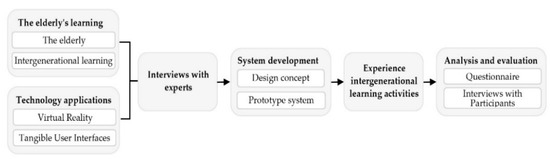

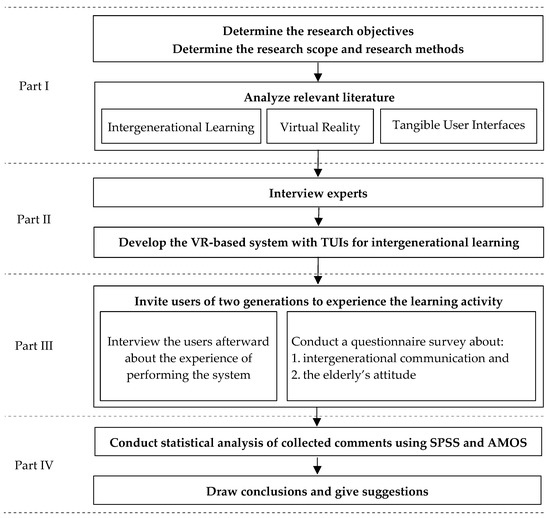

Figure 2 shows the framework of this study, which was mainly derived from the literature related to the elderly’s learning and technology applications. The design concept and system development were determined through interviews with experts. After constructing the system, actual intergenerational learning activities were held, and a questionnaire survey and participant interviews were conducted, with the results being analyzed and the effectiveness of the system evaluated.

Figure 2.

The framework of this study.

In this study, the research was mainly focused on intergenerational learning, and a novel tangible VR-based interactive system was proposed for such activities between the two generations of grandparents and grandchildren. Although previous studies, as mentioned in the previous literature survey, had various designs of intergenerational learning activities, the special case of adopting a traditional show performance, namely, glove puppetry, as the activity for intergenerational learning between the generations was not seen in the existing studies, which highlights the unique value of the proposed system and the resulting findings of this study.

The remainder of this manuscript is organized as follows. The proposed methods are described in Section 2. In Section 3, the results of our study are presented. The discussions of the experimental results are described in Section 4. Finally, the conclusions and discussions about the merits of the proposed system are included in Section 5.

2. Methods

A literature review, interviews with experts, the construction of a prototype system, a questionnaire survey, and interviews with participants were carried out in this study. Then, the effects of the system were analyzed. In particular, this study can be divided into four phases, as shown in Figure 3. In Phase I, the research objectives, scope, and methods were determined. Then, the relevant literature was analyzed, with key information on intergenerational learning, VR, and TUIs being collected. In Phase II, several experts in different fields were invited and interviewed to provide their comments on relevant topics that were determined according to the results of the literature review. The design principles for a VR-based intergenerational learning system using TUIs were derived based on the interview results. According to the principles, a prototype system for intergenerational learning was constructed, with relevant learning activities designed. In Phase III, users of two generations were invited to participate in the interactive intergenerational learning activities. In addition, comment data were collected through interviews with the participants and questionnaire surveys on the two aspects of intergenerational communication and the elderly’s attitude. In Phase IV, the collected data were used for statistical evaluations of the effectiveness of the developed system using the SPSS and AMOS software packages, and conclusions and suggestions were put forward finally.

Figure 3.

The flowchart of this study.

It is noteworthy that to use the proposed system, it requires the users’ interactions through actually experiencing activities, so the users, especially the elderly, are required to have sound audio–visual ability, and be able to conduct hand movements, beat gongs and drums, and perform hand gestures.

2.1. Interviews with Experts

Interviews with experts, as a form of interviews, allow interviewers to communicate with interviewees to collect research data [58]. Three experts, who were prominent in the fields of the elderly’s learning, children’s education, and interaction design, were invited (see Table 2 for the experts’ respective backgrounds). Experts were interviewed in a semistructural form, through which they expressed their opinions on four aspects: (1) the importance of intergenerational learning; (2) the design of intergenerational learning activities; (3) the introduction of digital technology into intergenerational learning; and (4) the introduction of VR into intergenerational activities. The results of the interviews were used as a reference for designing the desired system (see Section 3 for details).

Table 2.

Backgrounds of experts accepting interviews in this study.

2.2. Prototype Development

Boar’s prototyping model [59] was utilized in this study to understand the users of a product in the shortest time. Through the constructed prototype, the users’ responses were repeatedly evaluated, with their feedback serving as the basis for the designer to modify the product. In this way, the designer could have a clear idea of the users’ needs and finally create products that met their expectations. Beaudouin Lafon and Mackay [60] believed that a prototype could allow for a concrete presentation of an abstract system, provide information during the design process, and help the designer choose the best design scheme. Thus, based on Boar’s prototyping model, in this study the development of the desired intergenerational learning system based on VR and TUIs was planned in five steps, as follows: (1) planning and analyzing requirements; (2) designing the VR-based intergenerational learning system; (3) establishing a prototype of the VR-based intergenerational learning system; (4) evaluating and modifying the prototype system; and (5) completing the system development.

2.3. Questionnaire

The questionnaire for the system-effectiveness evaluation was modified several times after system development and before the experiment commenced. Fine adjustments were made later according to the evaluated effectiveness of the system to increase the stability of the system’s devices. The formal experimental questionnaire adopted in this study was divided into two parts. The first part adopted the Global Perceptions of Intergenerational Communication (GPIC) scale of McCann and Giles [61], in which questions were designed to learn how the two generations thought of each other in the intergenerational learning activities. In the second part, the Elderly’s Attitude Scale proposed by Lu and Kao [62] was employed to determine children’s attitudes toward the elderly in the experience. The answers to questions in the questionnaire were shown on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 meaning “strongly disagree” and 5 meaning “strongly agree” (see Section 3 for the detailed analysis and description of the questionnaire).

2.4. Interviews with Participants

After conducting the questionnaire survey, five groups of 10 participants were randomly selected for interviews. This qualitative research method focused on the interviewees’ self-perception and their descriptions of their life experiences. Particularly, researchers could comprehend the respondents’ cognition of facts based on their responses [63]. Semistructural interviews are flexible, allowing interviewees to convey their most authentic cognition and feelings [64]. They were so adopted in this study to explore the emotional exchange between the two generations and understand their perceptions of the VR-based interactive intergenerational learning system.

In addition, based on the interaction design principles proposed by Verplank [65], the following topics were determined for use in the interview conducted in this study: (1) system operation; (2) experiences and feelings; and (3) emotions and experience transmission. As assumed by Verplank [65], the most important thing in interaction design was participants’ physical and mental feelings; therefore, when designing an interaction device, designers must consider users’ system operations (DO), experiences and feelings (FEEL), and emotions and experiences (KNOW). The detailed interviews with users are presented in Section 3 below.

3. Results

3.1. Interviews with Experts

The questions in the interviews with experts were based on the selection mode of intergenerational learning and service activities proposed by Ames and Youatt [4] and the technology-acceptance model by Davis [37,38,39] to ensure the topics and direction of this study. The questions mainly covered four dimensions. Dimension One was mainly concerned with the importance of intergenerational learning, including its significance and influence in today’s society. Dimension Two involved the design of intergenerational learning activities, focusing on content presentation and other matters needing attention. Dimension Three involved the application of digital technology in intergenerational learning, focusing on the introduction method and views on the work. Dimension Four involved the introduction of VR to intergenerational activities, focusing on views of the interactive experiences, developments, and trends of VR-based intergenerational activities. Table 3 shows the outline and summary of the interviews with the experts.

Table 3.

Outline and summary of the interviews with experts.

In the interviews with experts, four key points were summarized. First, intergenerational learning plays an important role for the elderly and the young, bridging the gap between them and allowing them to learn from each other. Second, owing to the changes in the times and backgrounds, the progress of technology has widened the gap between the two generations. Therefore, if the elderly can actively learn about technology products and have more conversations with their grandchildren, they will find it easier to develop closer relationships with the latter. Intergenerational learning activities based on digital technology are more appealing to the young. Third, when designing intergenerational activities, the backgrounds and interests of the two generations should also be taken into account, and their common points should be identified to ensure participants’ full engagement in the interaction. Meanwhile, the difficulty of activities must be appropriate so that the two generations can have fun during the interaction. Fourth, concerning the interface design of intergenerational activities, the differences between the elderly and children regarding the font size, color, and visual and sound effects chosen must be considered.

In this study, the key factors of intergenerational learning, the introduction of technology, and the application of VR to system development and design were summarized through interviews with experts. According to the recording, analysis, and sorting of the interview information, the key points were used as a reference for the subsequent system design.

3.2. System Design

In this study, a novel system for intergenerational learning activities was designed. By integrating conventional learning activities with the uses of VR and TUIs, the communication, learning, and interaction between the two generations were strengthened through multiple interaction techniques and immersive experiences.

3.2.1. The Concept of Design of Intergenerational Learning Activities

According to the literature review, it is known that the topics involved in intergenerational learning activities must be familiar to the elderly and interesting to the young in order to encourage them to have more interactions. Therefore, in this study the traditional glove puppetry was chosen as the topic for the intergenerational learning activities. Glove puppetry has a long history in Taiwan, reaching its peak between the 1950s and 1960s. Hence, the elderly are rather familiar with it. On the other hand, according to the interviews with experts conducted in this study, experts majoring in children’s education deemed that children are easily attracted by cartoon characters and are generally interested in Muppets and dolls. Thus, they are likely to be curious about puppetry plays due to the cool sound and light effects created in such plays. Lastly, based on the selection model of intergenerational learning and service activities by Ames and Youatt [4], puppetry-based intergenerational activities suitable for this study were designed.

The theme of the designed activities was chosen to be “Recall the Play”, in which the word “recall” in Chinese has the same pronunciation as the word “together”, aiming at encouraging the elderly to perform glove puppetry together with the grandchildren. The elderly could recall the memories and feelings of watching puppet shows during their youth through interacting with their grandchildren. Meanwhile, sharing memories and stories of the past, as well as allusions to puppet shows, with grandchildren was a way of promoting cultural inheritance.

The activities were designed in such a way that they can be conducted through cooperation of the two generations, similar to the proscenium and backstage of a traditional open puppet-show theater, such as the example shown in Figure 4. In particular, while being assisted by instructions shown on a visible screen, a participant on the proscenium should make the corresponding gestures to manipulate the puppet in an animation. In the meantime, the other participant backstage must hit the corresponding musical instrument as instructed. If the participants follow the instructions correctly in time, the corresponding animation will be displayed correctly and smoothly.

Figure 4.

Real proscenium and backstage performances of a traditional glove puppet show: (a) proscenium; (b) backstage.

More specifically, regarding “Recall the Play” as a two-person cooperative experience system, its design concept is as illustrated in Figure 5, and mainly consists of two parts: puppetry and sound effects. In the puppetry part, an operator who is assumed to be on the proscenium wears an HTC VIVE headset to watch the performance of the role of a character, named Good Man, fighting another character, named Evil Person, in a puppet play from the first-person perspective, totally immersed in an on-the-spot experience. In addition, a Leap Motion sensor was mounted for gesture detection, allowing the operator to simulate the puppet gestures more intuitively. The sound effects of the second part were created to represent the soul of the puppet play in the real performance. An interactive installation with TUIs composed of a real drum, a gong, and a sound-sensing device was used to simulate the backstage performance in the real puppet show. The overall interactive scenario can be seen both on the headset screen and on an open system screen, which simulates what occurs during the performance in a traditional open puppet theater.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the proposed “Recall the Play” system.

Regarding the gesture-recognition method adopted in this research, two common gestures used in traditional glove puppet manipulation, namely, “rotation” and “flipping”, were simulated, using position vector and rotation angle matching techniques (please see Algorithm 1) provided by the Leap Motion sensor to realize the gesture-recognition task. This is a feature of the gesture-recognition task implemented in this study. Since only two kinds of gestures needed to be classified, the classification process is not complicated, and in the actual operations, almost all classification outcomes were correct, yielding good user performance results.

3.2.2. System Architecture

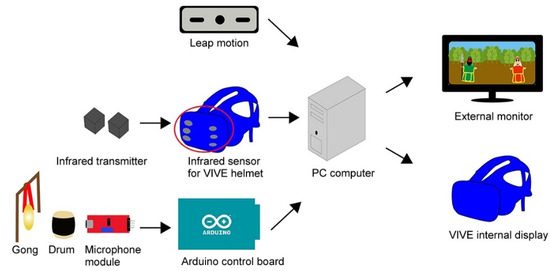

For system development to simulate the real performance in a traditional open theater as described previously, the hardware of the proposed system was designed to include: (1) the software package Leap Motion for human gesture detection; (2) an HTC VIVE headset for immersed VR; (3) an Arduino chipset for sound-signal analysis; (4) a microphone module for sound input; (5) a drum and a gong for backstage environment simulation; (6) a PC for system control; and (7) a screen for system display, which is subsequently called the system screen. Note that there is another screen within the VIVE headset that is subsequently called the headset screen. The software used in the system include the components of Unity 3D, Blender, Adobe Illustrator, Adobe Photoshop, and Adobe after Effects. Figure 6 shows the architecture of the proposed “Recall the Play” system.

Figure 6.

The framework of the proposed “Recall the Play” system.

Two types of interfacing—gesture detection and the use of the interactive installation—constitute the main input interaction part of the system. Specifically, in the gesture-detection process, the Leap Motion sensor detects the operator’s hand movements, identifies the motion type, and sends the corresponding signals to the PC end. Meanwhile, the VIVE headset receives infrared signals emitted by two position-fixed infrared transmitters, and sends them to the PC end for relative spatial positioning of the operator. This scheme is needed for precise VR environment creation on the VIVE internal display.

Regarding the interface when using the interactive installation, after receiving sound signals emitted by hitting the drum or gong, the microphone module first transmits them to the Arduino chip for preliminary analysis. Then, useful signals are filtered out and sent to the PC end for further processing. It was noteworthy that all signals are of the one-way output style. Finally, the PC analyzes the received signals and generates corresponding animation effects on the VIVE headset screen and the system screen on an external monitor.

The hardware devices used in the construction of the proposed system, as described above, are all replicable, and so the system essentially can be built in a DIY manner. In addition, the interactive interface operations of gong or drum beating, as well as the hand gestures, were simple to perform. Therefore, the cost of implementation of the system is inexpensive, and if the proposed system is to be used in future studies, there should be no technical problem with replications or applications.

3.2.3. Main Technologies

The main technologies used in the proposed “Recall the Play” system include two parts: gesture detection and sound sensing. Gesture detection mainly identifies the user’s hand movements. The corresponding interactive script will take effect to play the correct animations if the movements and times are in line with the given instructions. On the other hand, the sound-sensing devices check whether the user hit the correct musical instrument in the interactive installation backstage. The corresponding interactive animation will start if the instrument and beating times are consistent with the given instructions. The development environment, as well as the hardware and software used, are shown in Figure 6. Gesture detection and sound-sensing techniques using the related devices are described respectively as follows.

- (1)

- Gesture Detection

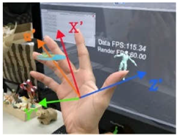

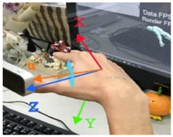

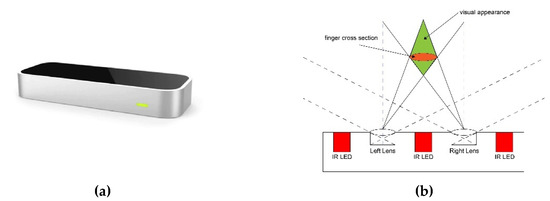

Leap Motion, as shown in Figure 7, is a gesture sensor device developed by Ultraleap that was adopted in the proposed “Recall the Play” system. In order to capture the user’s hand movements and identify the corresponding gestures in real time, two infrared cameras and three infrared LEDs in the Leap Motion sensor were used internally. The two internal infrared cameras are equipped in the device to simulate the binocular stereo vision of human eyes. By use of Leap Motion, hand movement data, especially those of the fingers, at 200 frames per second (FPS) can be acquired during the gesture-detection process and converted into the position coordinates of the hand and fingers. Specifically, in this study, when the user’s hands were rotated and moved, Leap Motion is used to capture the desired data and upload them to the PC every two seconds. In turn, the PC converts the data into position coordinates, from which the corresponding gestures are defined according to the changes in the coordinate axes. Lastly, the PC compares the uploaded and the defined gesture values to scrutinize whether they match each other as the result of gesture detection and recognition.

Figure 7.

Device used for gesture detection: (a) the Leap Motion device; (b) the principle of binocular imaging used by the Leap Motion controller.

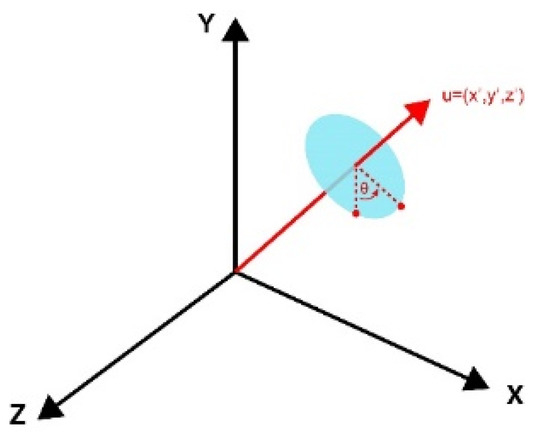

The proposed “Recall the Play” system mainly simulates the gestures of hand and finger manipulations of people using conventional puppets. The two major types of hand gestures selected for use in the system are finger rotation and finger flipping. These gestures are characterized by the rotations of palm joints. In order to more accurately distinguish the differences in finger rotations between the two gestures, the proposed system mainly use a rotation angle detection algorithm based on the quaternion and Euler’s rotation theorems. It is noted that these are commonly used principles, given that the manner in which they are expressed is simple.

Specifically, in Euler’s rotation theorem, when an object rotates in an arbitrary 3D space and at least one point is fixed, it can be interpreted that the object rotates around the fixed axis. This concept and that of quaternion rotation were used for gesture detection in this study. Quaternion represents a state of rotation in a 3D space with four numbers, namely, the three position coordinates x, y, and z, as well as the rotation angle w. Figure 8 shows the schematic diagram of the quaternion rotation matrix. A quaternion can be expressed as: q = ((x, y, z), θ) = (u, θ), where the vector u = (x, y, z) represents the coordinate values x, y, and z of the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively, and θ is a real number representing the rotation angle. In Table 4, a simple demonstration of the previously described gesture-recognition process of the proposed system is shown, which depicts how to recognize a finger-rotation gesture and a finger-flipping gesture.

Figure 8.

The Schematic Diagram of the Quaternion Rotation Matrix.

Table 4.

An illustration of gesture recognition.

Algorithm 1 shows the procedure of gesture detection implemented on the proposed system. The algorithm mainly detects a hand gesture (finger rotation or finger flipping) by matching the corresponding position coordinates and rotation angle values of the fingers at three checkpoints A through C. Note that at each checkpoint, a matching of the quaternion of the input hand movement with the reference one is conducted, which is called quaternion matching.

| Algorithm 1. Gesture Detection Algorithm. |

|

- (2)

- Sound Sensing

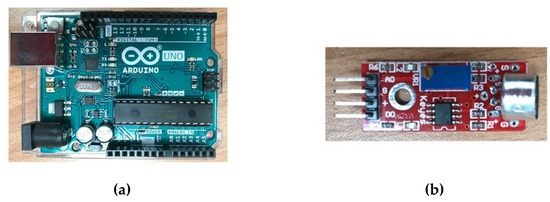

For the purpose of sound sensing, an Arduino chipset, as shown in Figure 9a, is connected to the microphone module, as shown in Figure 9b, to determine whether the user has beat a specified instrument (the drum or the gong). At the beginning of the interaction, the microphone module attached to the instrument begins to receive sound signals. Then, the signals are sent to the Arduino for noise filtering, where the real sound of the instrument being hit is examined further. If the volume of the real sound is found to be larger than a preset value, then a decision on drum or gong hitting is made, which is finally sent to the PC for further processing to generate the corresponding animation, as described subsequently.

Figure 9.

Hardware used for sound processing: (a) the Arduino chipset; (b) the microphone module.

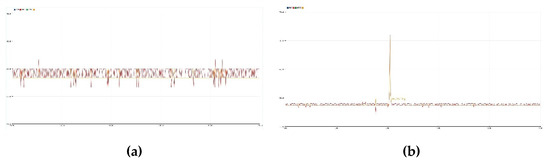

In more detail, the data of analog sound waves collected by the microphone were converted in this study into radio waves to demonstrate the range of the sound waves. The signal values stand around 27 dB indoors. When an instrument (the drum or the gong) of the interactive installation of the proposed “Recall the Play” system, as shown in Figure 10, was hit, the signal value significantly jumped from 27 dB to more than 60 dB, as shown in Figure 11. Since the volume of different instruments is affected by their loudness, timbre, and other factors, the preset values for sound detection can be adjusted according to the changes in the volume and the value of each instrument to avoid mutual interference of different instruments. Furthermore, to avoid ambient noise coming from the surrounding environment, it can be seen in Figure 11 that the sound signals from ambient and instrument waves are quite different, and so the ambient noise is easy to filter out. Table 5 shows the average volume values generated when the drum and the gong are played, and such values may be adopted as the threshold values for noise filtering.

Figure 10.

The gong and drum of the interactive installation of the proposed “Recall the Play” system and the wiring for sound-signal detection and transmission. (a) The front view of the installation; (b) the wiring.

Figure 11.

The data graphs of ambient and instrument waves: (a) ambient waves; (b) instrument waves.

Table 5.

Volume values of the instruments of the interactive installation.

Algorithm 2 shows the procedure of sound-detection algorithm implemented in this study for the proposed system. The algorithm mainly examines whether the volume of the sound continuously collected by the microphone exceeds a preset value and whether the sound matches that of the instrument specified by the system to ensure whether the correct instrument (drum or gong) is hit.

| Algorithm 2. Sound Detection and Instrument Beating Verification. |

|

- (3)

- Types of gestures designed for generating animations

The proposed “Recall the Play” system designed for intergenerational learning combines VR and TUIs as the interface for interactive learning activities. It is noteworthy that the diverse interactions and immersive experiences provided by the system enhance the effects of learning and interaction between the two generations. Four types of interactive gestures, namely, finger rotation, finger flipping, drum beating, and gong beating, as shown in Table 6, were designed for use by the participants in the interactive learning activities. The total time duration of a cycle of interaction in the animation shown both on the headset screen and the system screen is 120 s. One of the icons representing the above-mentioned four types of gestures is shown randomly every 2 s on the screens for the two operators on the proscenium and backstage to see and follow.

Table 6.

Four types of interactive gestures used in the proposed system.

- (4)

- System Flow of Intergenerational Learning via Puppetry

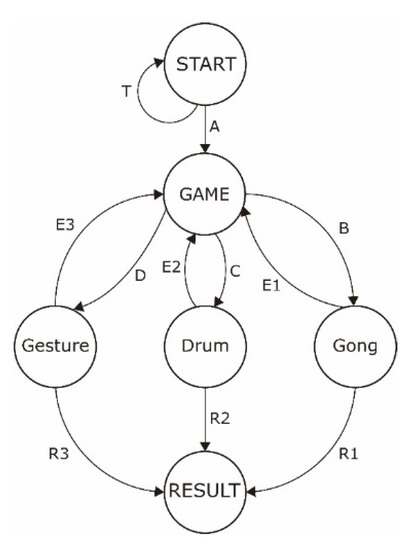

The state diagram of the system flow for experiencing the proposed “Recall the Play” system is shown in Figure 12, and the detailed descriptions of the state transition flows are given in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3. State Transitions of the System Flow of the Proposed System. |

if the elapse time te in this state ≥ 2 s and the cycle time tc < 120 s, then follow flow E1 to get into the GAME state; //Keep playing the game. else follow flow R1 to get into the RESULT state. //Go to end the game.

if the elapse time te in this state ≥ 2 s and the cycle time tc < 120 s, then follow flow E2 to get into the GAME state; //Keep playing the game. else follow flow R2 to get into the Result state. //Go to end the game.

if the elapse time te in this state ≥ 2 s and the cycle time tc < 120 s, then follow flow E3 to get into the GAME state; //Keep playing the game. else follow flow R3 to get into the Result state. //Go to end the game.

|

Figure 12.

The state diagram of participants experiencing the proposed system.

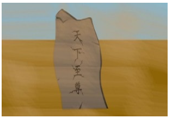

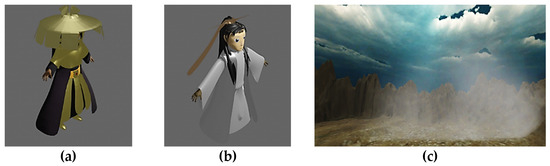

3.2.4. Visual Design

The visual designs of the two 3D characters—the Good Man and the Evil Person—and the scene of the environment where the war between them was held in the puppet show animations are shown in Figure 13. They were designed in such a way to simulate the images of the puppets and environment in the real traditional show Wind and Clouds of the Golden Glove-Puppet Play so as to arouse the memory of the elderly involved in using the proposed “Recall the Play” system.

Figure 13.

The 3D modeling of the characters and environment scenes of the puppet-show game played on the proposed “Recall the Play” system: (a) 3D model of the Evil Person; (b) 3D model of the Good Man; (c) 3D model of the environment scene.

3.2.5. An Example of Results of Running the Proposed “Recall the Play” System

The intermediate interaction results of an example of running the proposed “Recall the Play” system to perform a puppet show is shown in Table 7, which includes the intermediate animations of the major steps in the show.

Table 7.

List of intermediate interaction results of an example of running the proposed system.

3.3. Experimental Design

In this study, both VR and TUIs technologies were applied to intergenerational learning for the two generations: the grandparent and the grandchild. Additionally, activities on the “Recall the Play” system were displayed in several exhibition halls, including the Bald Pine Forest in Nantou, the Puppets’ House in Dounan, the Yunlin, and the Dali Community Care Base in Taichung, which are all located in Taiwan, as shown in Figure 14 and Figure 15.

Figure 14.

Scene setting of the proposed “Recall the Play” system.

Figure 15.

Experiencing the intergenerational activity on the proposed “Recall the Play” system: (a) Case 1; (b) Case 2.

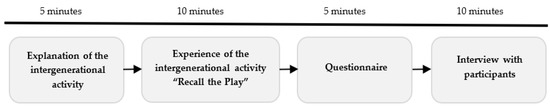

The participation of a pair including a grandparent and a grandchild was estimated to last approximately 30 min in each game play on the proposed system. When the grandparent and the grandchild entered the field, the first step taken by the staff of this study was to briefly explain the concepts and procedures of the system to them for five minutes. Then, they joined the intergenerational activity on the “Recall the Play” system for 10 min. After the experiencing process, a questionnaire survey of their opinions was conducted for five minutes. Lastly, five pairs of grandparents and grandchildren, comprising 10 participants, were randomly selected to be interviewed. The aforementioned experimental procedure is shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Design of Experimental Procedures.

The length of the total time used for the formal experimental procedure conducted in this study was the result of a deliberate decision for the test groups, which included young children and old people. In general, children cannot concentrate on an activity for very long during the system-experiencing process. On the other hand, the elderly’s physical and mental conditions should be taken into consideration in the experiencing process; if the operation time is too long, they might experience slight dizziness and discomfort.

Accordingly, the activity script for the proposed mutual learning activity was designed to not be too complicated, so that the entire formal experimental procedure could be completed within 30 min; the specific time for experiencing the intergenerational activity was set to be 10 min, which was enough to complete the proposed activity.

Regarding the 10 min activity in which one user was conducting a VR experience by wearing a headset, although the user could relax his/her mind and enjoy the virtual immersive environment during this activity, if the audiovisual experience in the VR environment is too strong, it will cause contrary interference for the user. This interference is in particular more serious to the elderly users, because the visual and auditory senses of the elderly decline with age. Therefore, the VR-experiencing time must not be too long, and so was set to be 10 min, as stated above. In short, the original plan of time usage was considered appropriate. In addition, since the story script was short, a merit followed; namely, it did not require an extensive background environment for conducting the experiment.

In the future, extensions of this study can be designed to have richer story scripts and allow longer activity-experiencing times with more gorgeous background environments for use by a larger range of generations, instead of being limited to the two generations of grandparents and grandchildren.

3.4. Questionnaire Survey Results

A total of 120 copies of questionnaires were collected from 60 pairs of grandparents and grandchildren. Each questionnaire included questions about the participant’s basic data, as well as the evaluations of the two indicators of the GPIC scale and the elderly’s attitude scale. The basic data are shown in Table 8, in which it can be seen that 70% of the participants had never experienced VR before, while 30% of the participants had previously used a VR system.

Table 8.

Basic data of the participants obtained in the questionnaire survey.

In addition, among the 120 collected questionnaires, 114 copies from 57 pairs were valid, and 6 from 3 pairs were invalid. Each questionnaire also included questions about and the evaluations of the two indicators of the GPIC scale and the elderly’s attitude scale, with the former indicator involving both the elderly and the children, and the latter concerning only the children. The questions of the two indicators are shown in the second column of Table 9, with questions S1–S9 being related to the first indicator, and T1–T15 related to the second. Some statistics of the collected feedback data of the Likert 5-point scale of the two indicators are listed in Table 9 and Table 10; these were analyzed in detail from several points of view, as described in the following.

Table 9.

Questions and average statistics of the data of the two indicators of the GPIC scale and the elderly’s attitude scale obtained in the questionnaire survey.

Table 10.

Detailed statistics of the data of the two indicators of the GPIC scale and the elderly’s attitude scale obtained in the questionnaire survey.

Table 9 includes questions about the children’s feelings toward the elderly’s behaviors in the system-experiencing process that were filled out by the participating children. The standard deviations of T6, T10, and T13 in the table are greater than 1, which reflect the children’s divergent feelings about their grandparents’ willingness to learn new things or interests in acquiring new knowledge, as well as their cognition of the elderly’s passiveness in these activities.

3.4.1. Designing Processes for Testing the Properties of the Collected Data

In this study, the SPSS and AMOS software packages were used to analyze the collected questionnaire data. A series of tests were conducted to verify the properties of the collected data to ensure that the data could be analyzed to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed system for intergenerational learning. The data properties and the methods adopted to verify them are listed in the following, with the details described later in this section.

- Adequacy of the collected data—verified by the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity using the SPSS package.

- Latent dimensions (scales) of the questions used in collecting the data—found by exploratory factor analysis (EFA) via the principal component analysis (PCA) method and the varimax method with Kaiser normalization using the SPSS package.

- Reliability of the collected data—verified by using the Cronbach’s α coefficient values yielded by the EFA process.

- Suitability of the model structure of the data setup based on the found question dimensions (scales)—verified by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the AMOS package.

- Validity of the collected questionnaire data—verified by the parameter values yielded by the EFA and CFA processes.

3.4.2. Testing the Adequacy of the Collected Data

To evaluate the adequacy of the collected questionnaire data listed in Table 9 and Table 10, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity were adopted in this study [66,67,68,69,70,71]. The KMO measure is a statistic used to indicate the proportion of variance among the variables that may possibly be caused by certain factors underlying the variables. The KMO test returns measure values in the range of 0 to 1, and Kaiser [69] assigned the returned values into six categories: (1) unacceptable—0.00 to 0.49; (2) miserable—0.50 to 0.59; (3) mediocre—0.60 to 0.69; (4) middling—0.70 to 0.79; (5) meritorious—0.80 to 0.89; and (6) marvelous—0.90 to 1.00. A KMO measure value larger than the threshold value of 0.50 is usually regarded to pass the test [66,67].

Additionally, the Bartlett’s test of sphericity is employed to test the hypothesis that the correlation matrix of the data variables is an identity matrix, which indicates that the variables are unrelated. A significance value of the test result smaller than the threshold value of 0.05 is usually considered as acceptable to reject the hypothesis, or equivalently, to pass the test [67,68]. When both of the two tests are passed, the data variables are usually said to be adequately related for further structure analysis [70].

By using the collected questionnaire data and their statistics shown in Table 9 and Table 10, the KMO measure values and the significance values of the Bartlett’s test for the two indicators were computed by the SPSS, and are listed in Table 11. It can be seen in the table that for either indicator, the KMO measure value is larger than the threshold of 0.5 and the significance value of the Bartlett test is smaller than the threshold 0.05. Consequently, it was concluded that the datasets of both indicators of the GPIC Scale and the Elderly’s Attitude Scale were adequately related for further structure analysis, as described next.

Table 11.

The measured values of the KMO test and the significance values of Bartlett’s test of the data collected for the GPIC scale and the elderly’s attitude scale.

3.4.3. Finding the Latent Dimensions (Scales) of the Questions from the Collected Data

With the adequacy of the questionnaire data being verified as described above, the SPSS package was used further to perform an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using a principal component analysis. In addition, the varimax method with Kaiser normalization was employed to find suitable latent dimensions (scales) for the questions with the collected data as inputs. The details of the results are listed in Table 12 and Table 13. It was found accordingly that the nine questions (S1–S9) of the first indicator, global perceptions of intergenerational communication (GPIC), could be divided into three groups under the question dimensions (scales) of accommodation, nonaccommodation, and avoidance, respectively. The 15 questions (T1–T15) of the second indicator, the elderly’s attitude, could be divided into three groups as well under the question dimensions (scales) of psychological cognition, social engagement, and life experience, respectively. The results of such latent dimension (scale) findings, with some statistics of the data of the Likert scale included, are shown integrally in Table 14.

Table 12.

Rotated component matrix of the indicator of GPIC.

Table 13.

Rotated component matrix of the indicator of the elderly’s attitudes.

Table 14.

Analysis of the question dimensions (scales) of GPIC and the elderly’s attitude by SPSS.

3.4.4. Verifying the Reliability of the Collected Data Using the Cronbach’s α Coefficients

Reliability is about the consistency of a measured dataset despite the repeated times [72]. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient [73,74] yielded by the EFA mentioned previously was adopted to analyze the reliability of the collected questionnaire data. It is known that the closer the Cronbach’s α coefficient of a dataset of a scale is to the extreme value of 1.0, the greater the reliability of the dataset (regarded as variables) is. Based on Gildford [75], the following rules may be used to judge the degree of reliability of a dataset:

where α is the Cronbach’s α coefficient value of the dataset.

α ≤ 0.35 — unreliable

0.35 ≤ α < 0.70 — reliable

α ≥ 0.70 — highly reliable

The Cronbach’s α coefficient values of the six question dimensions (scales) and those of the two indicators are shown integrally in Table 15. It can be seen in the table that all the Cronbach’s α coefficient values are in the range of 0.35 to 0.70 or even larger, meaning that the collected questionnaire dataset of each question dimension, as well as those of each indicator are reliable.

Table 15.

Collection of the data of the indicators of GPIC and the elderly’s attitudes and the Cronbach’s α coefficients of the six question dimensions of the two indicators.

3.4.5. Verification of the Applicability of the Structural Model Established with the Question Dimensions (scales)

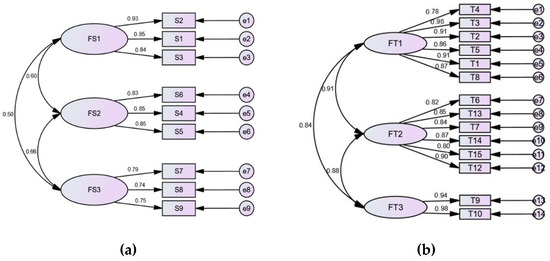

Before proving the validity of the collected questionnaire data, the suitability of the structure model set up by the question dimensions (scales) need be verified [76]. For this purpose, the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) process using the AMOS package was applied on the collected questionnaire data, yielding two three-scale structure-model graphs, as shown in Figure 17. Moreover, a list of structure-model fit indices was yielded by the CFA for each indicator, including the degrees of freedom (df), the chi-square (χ2) statistics, the ratio of χ2/df, the adjusted goodness-of-fit index (gfi), the comparative fit index (cfi), and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), as shown integrally in Table 16. Accordingly, the index values of χ2/df, gfi, cfi, and RMSEA yielded for each indicator show the fact that the structure model set up by the question dimensions (scales) of the indicator is of a reasonably good fit to the collected questionnaire data [77,78,79,80,81].

Figure 17.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the AMOS package. (a) Diagram of the three-scale structural model of the GPIC indicator (FS1: accommodation; FS2: nonaccommodation; FB3: avoidance) generated through CFA; (b) diagram of the three-scale structural model of the elderly’s attitude indicator (FT1: psychological cognition; FT2: social interaction; FT3: life experience) generated through CFA.

Table 16.

Fitness indexes of the structural models of the two indicators of GPIC and the elderly’s attitudes generated through CFA.

3.4.6. Verification of the Validity of the Collected Questionnaire Data

With the model structures of the two indicators both being proved to fit reasonably to the collected questionnaire data, it was proper to analyze further the validity of the data. It can be seen from the three-scale structure model shown in Figure 17 that all the factor-loading values (also called standardized regression weights) with respect to the scales (appearing on the paths of the scales FS1–FS3 and FT1–FT3 to the questions S1–S9 and T1–T15, respectively) are all larger than the threshold of 0.5. This indicates that the construct validity of the model was verified. This fact can also be proved by the construct validity values of all the scales of the two indicators of GPIC and the elderly’s attitudes yielded by the EFA process mentioned above, because such values, as listed in Table 17, can be observed to all be larger than the threshold value of 0.6 [82,83]. That is, the construct validity of the collected questionnaire data of the indicator of system usability is proven.

Table 17.

Valid values of the question dimensions (scales) of the two indicators of GPIC and elderly’s attitudes generated through CFA.

3.4.7. Summary of Analyses Based on the Content of the Collected Questionnaire Data

It can be concluded from the above discussions that the questionnaire data collected from the participants regarding the two indicators of GPIC and the elderly’s attitudes are both reliable and valid for uses in further analyses of the data contents, which lead to the following conclusions.

- (A)

- Analysis of the Indicator of GPIC

The overall feedback on the questionnaire regarding the evaluation of GPIC was positive. As shown in the upper part of Table 10, the average percentage of agreement was 80.9%, indicating that the participants felt good about the communication between grandparents and grandchildren in the experiences of using the proposed system. Furthermore, McCann and Keaton’s GPIC scale [61] consists of two perspectives for the survey data collected in this study: “perception of others’ communication” and “perception of one’s communication”. The former perspective was divided into the dimensions of accommodation and nonaccommodation in this study. Accommodation refers to a participant’s perception that the other participant is friendly and kind during the interaction. Meanwhile, nonaccommodation referred to a participant’s perception that the other is more competent during the interaction and can recognize their advantages. The other perspective, “perception of one’s communication,” has only one dimension—avoidance. Avoidance refers to a subject making a concession for some reason or in some circumstances when interacting with others.

The average score of S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5 in the nine questions on the indicator of GPIC was higher than 4.17, indicating that more than 80% of the participants approved of the intergenerational communication during the interaction. However, the score data show in the meantime that the awareness of other people was obviously higher than self-awareness, with a sense of friendliness and intimacy. In addition, as seen in Table 9 and Table 10, the question S7 yields a lower score with a standard deviation value larger than one because a small number of users gave it just one point. This fact indicates that the users had different views on compromising in the interaction process using the proposed system.

More generally, based on the data-analysis results shown in Table 9 and Table 10 regarding the indicator of GPIC, the following conclusions were drawn:

- During the interaction, the grandparents and grandchildren were friendly and kind to each other.

- During the interaction, the grandparents and grandchildren recognized each other’s strengths.

- During the interaction, the grandparents and grandchildren would mostly restrain themselves, reserve their own opinions, and keep silent when they disagreed with each other.

- Nevertheless, it was also found that when the two parties had different opinions, they would still acknowledge each other’s advantages and friendliness during the interaction.

- (B)

- Analysis of the Elderly’s Attitudes

Most of the questions received positive feedback regarding the elderly’s attitudes. As shown in the second part of Table 10, the average agreement rate was 82.7%, indicating a good overall evaluation of the interaction between the children and the elderly.

More specifically, the average scores of 9 of the 15 questions (T1, T3, T7, T8, T9, T10, T12, T14, and T15) were above 4.33. The second part of Table 10 shows that the average agreement rate was 82.7%, and according to Table 9, the children were seen to think that the elderly held positive attitudes. The highest score, T8, indicated that the children psychologically believed their grandparents were trustworthy. The two questions with lower scores are T13 and T6. Based on the data analysis of the elderly’s attitudes felt by the children, the following conclusions were drawn:

- During the interaction, the grandparents were psychologically reliable to the children.

- During the interaction, the grandparents were kind, smart, and happy as felt by the children psychologically.

- During the interaction, the grandparents were kind, smart, and happy as felt by the children cognitively.

- During the interaction, the children had a positive psychological and cognitive perception of the elderly.

3.4.8. Evaluation of System Effectiveness from the Perspectives of GPIC and the Elderly’s Attitudes

In the evaluation of the system effectiveness from the perspective of GPIC, the average scores of the three dimensions of “accommodation”, “nonaccommodation”, and “avoidance” are larger than four, and the agreement rates (including the rates of “strongly agree” plus “agree”) are greater than 85%, as shown in Table 18 and Table 19, which were computed using Table 9 and Table 10. In addition, the average scores range from 4.02 to 4.35, all of which are greater than 4. These results indicate that grandparents and grandchildren performed well in communication during the interaction.

Table 18.

Evaluation of the average scores of GPIC and the elderly’s attitudes from the perspectives of the two indicators.

Table 19.

Evaluation of the percentages of GPIC and the elderly’s attitudes from the perspectives of the two indicators.

Meanwhile, in the evaluation of the system effectiveness from the perspective of the elderly’s attitudes, the average scores of the three dimensions of “psychological cognition”, “social interpersonal participation”, and “life experience” are larger than four, and the agreement rates (including the rates of “strongly agree” plus “agree”) are greater than 80%, as shown in Table 18 and Table 19. In addition, the average scores range from 4.32 to 4.34, all of which are greater than 4. These results indicate that the elderly showed good attitudes during the interaction as felt by the children.

It is noteworthy that the average score for the elderly’s attitudes is 4.33, higher than that of GPIC, which is 4.17. This fact indicates that the children had positive psychological and cognitive experiences during the interaction with the elderly, and that the psychological cognition and life experiences of the elderly were felt as positive attitudes by the children.

3.5. Analysis of Interviews with Participants

Based on Verplank’s interaction design principles [65], in this study the participants’ feelings about their experiences when using the proposed system were investigated via interviews with the participants. The interviews mainly focused on the aspects of system operation (labeled as DO), feeling of experiencing the system (labeled as FEEL), and communication of emotion and experience (labeled as KNOW). For DO, the questions for the participants included the aspects of system operation, interface, and design difficulty. For FEEL, the problem design was based on the participants’ feelings during and after the activities, as well as other related thoughts. Lastly, the part of KNOW involved the investigation of the participants’ emotional communication and inheritance of relevant memories after experiencing the system, which was also the main design purpose of this study’s prototype system. After conducting the intergenerational activities and the questionnaire survey, 10 users representing five pairs of grandparents and grandchildren were randomly selected for interviews. During the interview procedure, their responses were recorded using audio recorders and in writing. The participants’ responses are summarized in Table 20.

Table 20.

Record data of interviews with participants.

According to the results of interviews with the participants listed in Table 20, most of them gave positive feedback on the two aspects of feeling of experiencing the system (FEEL) and communication of emotion and experience (KNOW). For the aspect of system operation (DO), the participants gave many suggestions, such as making slight adjustments to the gestures, providing a greater variety of images on the screen, and making the overall operation easier to understand. In addition, the participants who had experience in manipulating puppets were faster at playing with the puppets in the VR environment. In more detail, the conclusions that are drawn based on the interview results shown in Table 20 are the following.

- (1)

- Interview results for the aspect of system operation (DO):

- (a)

- After playing the drums and manipulating the puppets with VR gestures, participants found the operations of the gong and the drum more intuitive and easier to understand.

- (b)

- Most participants were not puppeteers, and gestures that were too professional were not easy for those inexperienced to perform.

- (2)

- Interview results for the aspect of feeling of experiencing the system (FEEL):

- (a)

- The young participants preferred interactions with more sound and light effects or with more variations.

- (b)

- The children preferred operating the gong and the drum to performing VR actions.

- (3)

- Interview results for the aspect of communication of emotion and experience (KNOW):

- (a)

- Older experienced participants learned puppetry more quickly than those without puppetry experiences, and they could impart to their grandchildren more knowledge about puppetry.

- (b)

- In the intergenerational learning activities, the grandparents and grandchildren would increase the exchange of mutual learning experiences.

Furthermore, usability is an important evaluation item of an interactive system. Using the content of Table 20 regarding the aspect of System Operation (DO), the following is a short summary of the usability related to our research.

- (1)

- The participants knew how to operate the system, since it was easy to play the drum and the gong.

- (2)

- The participants did not know how to make the gestures initially, but they succeeded later after operating the system for a while.

- (3)

- The participants felt that it was easy to use the interface, as the scenes and characters were lifelike to a degree.

3.6. Summary of Experimental Results

The major research findings of this study drawn from the above analysis results are listed in Table 21, and are organized from the perspectives of three previously published studies: (a) McCann and Giles [61], with the perspective of global perceptions of intergenerational communication (GPIC); (b) Lu and Kao [62], with the perspective of the elderly’s attitude scale; and (c) Verplank [65], with the perspective of interviews with system participants.

Table 21.

Summary of the major research findings of this study.

4. Discussions

With the advent of aging societies and changes in family structures, intergenerational learning has become increasingly important in the current era. On the other hand, fast technology development has become the trend of the future in the 21st century, which makes integrating technologies into conventional intergenerational activities, as well as group learning or education, a long-term issue worthy of serious consideration. For example, Kyrpychenko et al. [27] proposed a good structure of communicative competence for teaching a foreign language to higher education students, and Kuzminykh et al. [28] proposed self-education and group-education approaches to the development of teaching competence. These diverse research directions and results further highlight the importance of the intergenerational learning issue investigated in this study, and offer useful insights for developing the system design principles of this study.

It was the main focus of this study to educate people of the older generation who were unfamiliar with fast-developing technologies. The aim was mainly to make technology more acceptable to them to narrow the gap between the young and the old. Therefore, a novel learning system was proposed in this study, with traditional puppetry being introduced as the theme, based on the life experiences of the older generation. By introducing digital technology into intergenerational learning and applying VR and TUIs in the learning activities, the two different generations could increase their communication and interaction, thereby achieving emotional exchange and the sharing of experiences. More findings of facts in this research are elaborated in the following.

4.1. Findings of System-Development Principles

In this study, different subjects and activities based on the literature related to intergenerational activities were reviewed. In addition, existing cases on introducing intergenerational learning and VR technology to the older generation were surveyed. After deep discussions with invited experts, four design principles for the system development of VR-based intergenerational learning were created:

- (1)

- intergenerational activity themes should be interesting to both generations;

- (2)

- the interface should be as simple as possible;

- (3)

- the operations of the system should be intuitive;

- (4)

- the performance of the system should include slightly stimulating ways of interaction.

The prototype system developed in this study was based on the experts’ advice and the above-mentioned design principles. After many tests and modifications, a new intergenerational learning system was constructed that was familiar to both generations and allowed them to promote emotion exchange.

4.2. Findings from Questionnaire Survey Results

The questionnaire data collected from the participants who experienced the prototype system were analyzed by SPSS and AMOS, and the results showed that the data of the two indicators, GPIC and the elderly’s attitudes, were reliable and valid for further evaluation of the system’s effectiveness. The average values of the data of the two indicators are both larger than 4 points on a 5-point Likert scale, indicating that the participants’ attitudes toward each other in the process of experiencing the intergenerational learning activities provided by the proposed system are relatively positive. In more detail, the following conclusions were drawn from the results of the questionnaire data analyses and the interviews with the participants:

- (1)

- The children preferred active interaction, such as playing the drum and the gong, while the older participants preferred simple and easy interactions.

- (2)