Applying Marine Protected Area Frameworks to Areas beyond National Jurisdiction

Abstract

:1. Introduction

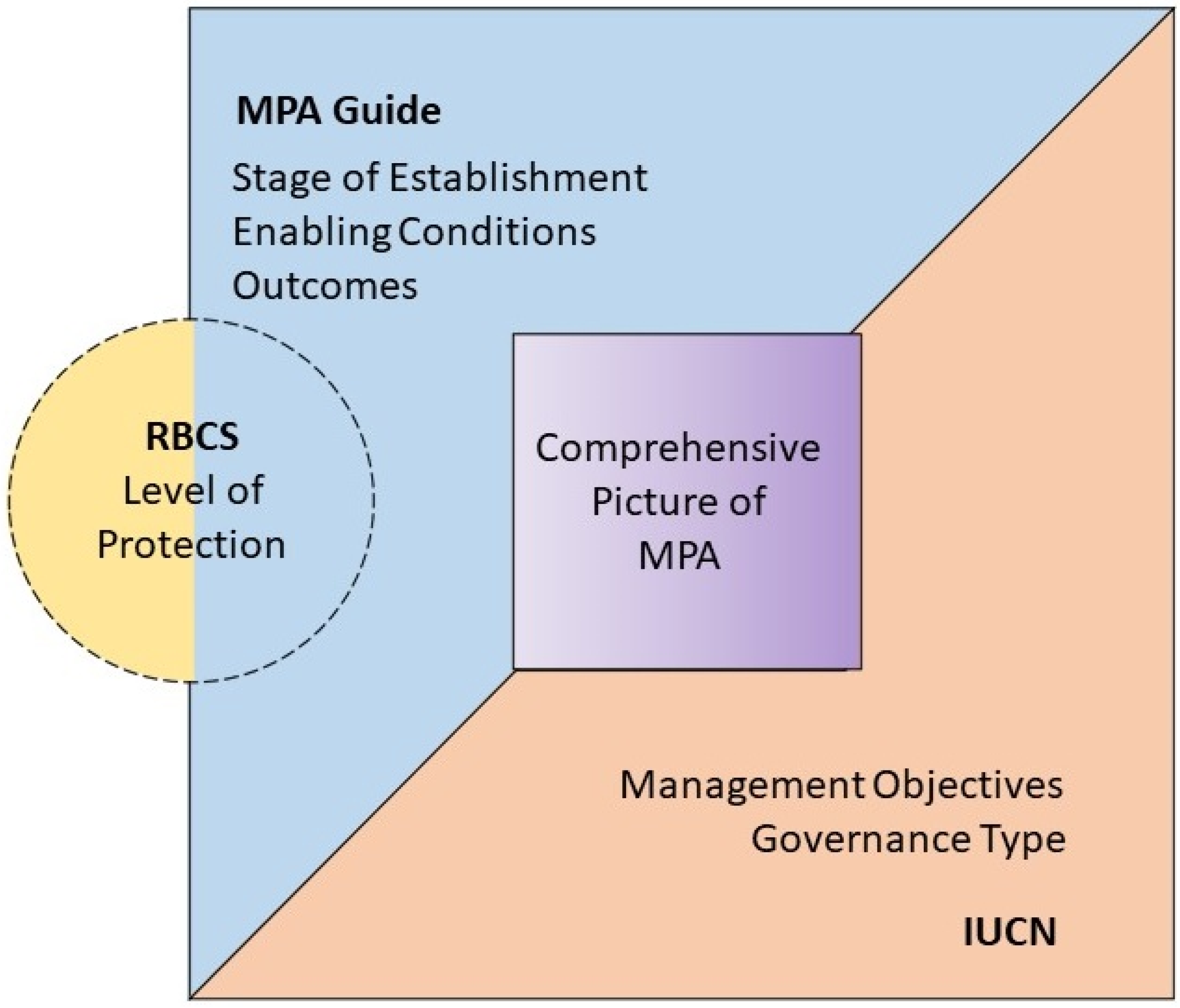

1.1. MPA Frameworks: IUCN MPA Guidelines and The MPA Guide

1.2. Defining MPAs for this Study

“A protected area is a clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values.”

1.3. Governance of ABNJ MPAs

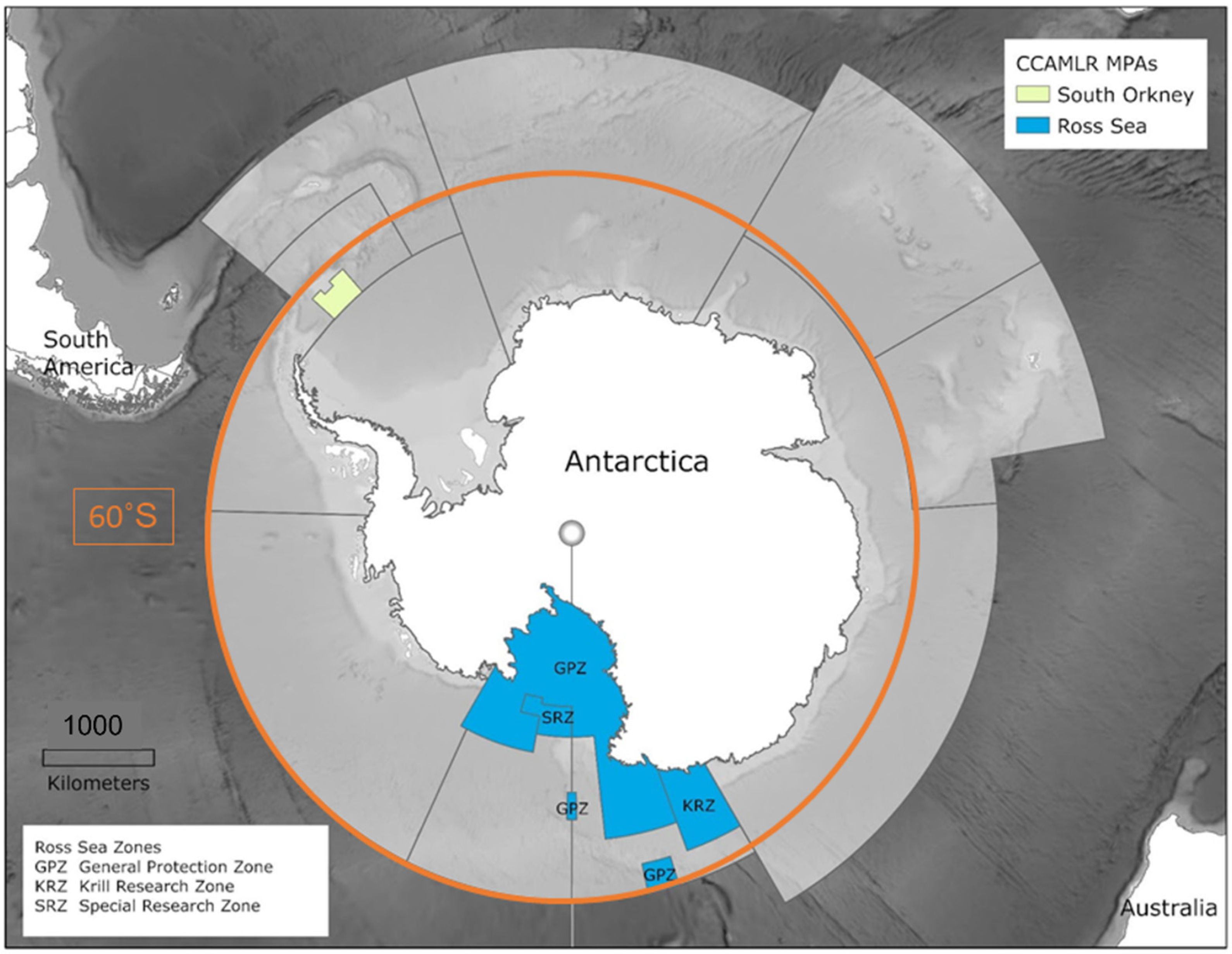

1.4. CCAMLR’s Governance Structure

2. Methods

2.1. Data Gathering

2.2. Application of MPAs Frameworks and Criteria to Existing High Seas MPA

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. IUCN Category (2019 MPA Guidelines)

3.2. The MPA Guide

3.2.1. Stage of Establishment

3.2.2. Level of Protection

Mining and Oil Extraction

Dredging, Dumping, and Discharges

Anchoring

Infrastructure

Aquaculture

Fishing

Non-extractive Activities

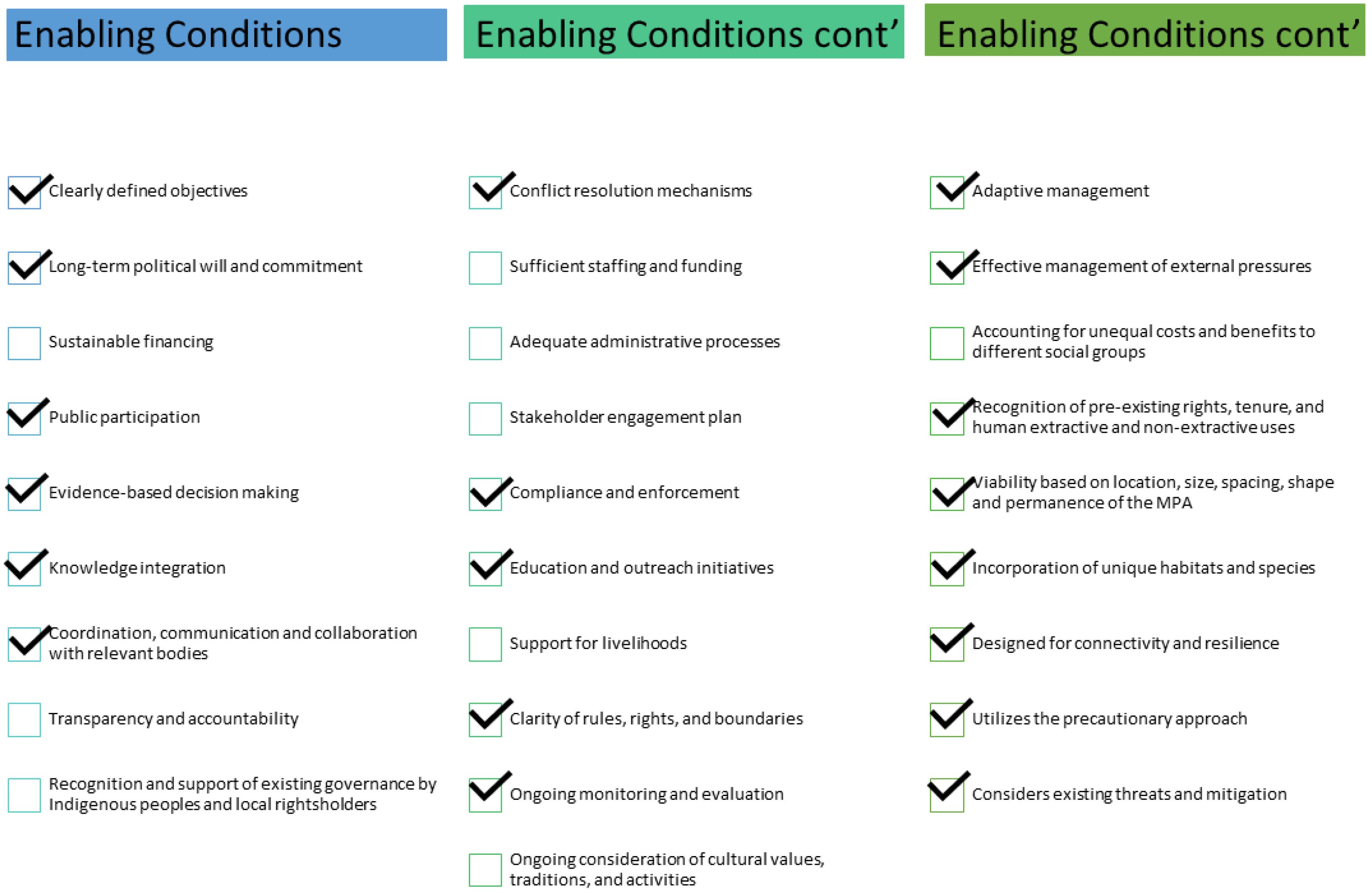

3.2.3. Enabling Conditions

3.3. Addressing Research Fishing

3.4. Outcomes: CCAMLR’s Strengths and Limitations

BBNJ Broader Implications

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Santo, E.M. Implementation challenges of area-based management tools (ABMTs) for biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ). Mar. Policy 2018, 97, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, B.C.; Ban, N.C.; Fernandez, M.; Friedlander, A.M.; García-Borboroglu, P.; Golbuu, Y.; Guidetti, P.; Harris, J.M.; Hawkins, J.P.; Langlois, T.; et al. Addressing Criticisms of Large-Scale Marine Protected Areas. BioScience 2018, 68, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gjerde, K.M.; Reeve, L.L.N.; Harden-Davies, H.; Ardron, J.; Dolan, R.; Durussel, C.; Earle, S.; Jimenez, J.A.; Kalas, P.; Laffoley, D.; et al. Protecting Earth’s last conservation frontier: Scientific, management and legal priorities for MPAs beyond national boundaries: Priorities for MPAs beyond National Boundaries. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2016, 26, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Day, J.C.; Dudley, N.; Hockings, M.; Holmes, G.; Laffoley, D.; Stolton, S.; Wells, S. Guidelines for Applying the IUCN Protected Area Management Categories to Marine Protected Areas, 1st ed.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2012; ISBN 978-2-8317-1524-7. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, G.J.; Stuart-Smith, R.D.; Willis, T.J.; Kininmonth, S.; Baker, S.C.; Banks, S.; Barrett, N.S.; Becerro, M.A.; Bernard, A.T.F.; Berkhout, J.; et al. Global conservation outcomes depend on marine protected areas with five key features. Nature 2014, 506, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Leary, B.C.; Hoppit, G.; Townley, A.; Allen, H.L.; McIntyre, C.J.; Roberts, C.M. Options for managing human threats to high seas biodiversity. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 187, 105110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, B.S. The Impact of Marine Reserves: Do Reserves Work and Does Reserve Size Matter? Ecol. Appl. 2003, 13, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, L.A.; Beyer, H.L.; O’Hara, C.; Watson, J.E.M.; Dunn, D.C.; Halpern, B.S.; Klein, C.J.; Frazier, M.R.; Kuempel, C.D.; Williams, B.; et al. Multinational coordination required for conservation of over 90% of marine species. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 27, 6206–6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selig, E.R.; Bruno, J.F. A Global Analysis of the Effectiveness of Marine Protected Areas in Preventing Coral Loss. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sala, E.; Giakoumi, S. No-take marine reserves are the most effective protected areas in the ocean. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2018, 75, 1166–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leary, D.; Vierros, M.; Hamon, G.; Arico, S.; Monagle, C. Marine genetic resources: A review of scientific and commercial interest. Mar. Policy 2009, 33, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaustein, R.J. High-seas Biodiversity and Genetic Resources: Science and Policy Questions. BioScience 2010, 60, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sala, E.; Mayorga, J.; Costello, C.; Kroodsma, D.; Palomares, M.L.D.; Pauly, D.; Sumaila, U.R.; Zeller, D. The economics of fishing the high seas. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Watling, L.; Auster, P.J. Seamounts on the High Seas Should Be Managed as Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crespo, G.O.; Dunn, D.C.; Gianni, M.; Gjerde, K.; Wright, G.; Halpin, P.N. High-seas fish biodiversity is slipping through the governance net. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 1273–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visalli, M.E.; Best, B.D.; Cabral, R.B.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Clark, N.A.; Garilao, C.; Kaschner, K.; Kesner-Reyes, K.; Lam, V.W.Y.; Maxwell, S.M.; et al. Data-driven approach for highlighting priority areas for protection in marine areas beyond national jurisdiction. Mar. Policy 2020, 122, 103927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgian, S.; Morgan, L.; Wagner, D. The modeled distribution of corals and sponges surrounding the Salas y Gómez and Nazca ridges with implications for high seas conservation. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmine, G.; Mayorga, J.; Miller, N.A.; Park, J.; Halpin, P.N.; Crespo, G.O.; Österblom, H.; Sala, E.; Jacquet, J. Who is the high seas fishing industry? One Earth 2020, 3, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.J.; Brown, C.J.; Halpern, B.S.; Segan, D.B.; McGowan, J.E.M.; Beger, M.; Watson, J. Shortfalls in the global protected area network at representing marine biodiversity. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roberts, K.E.; Valkan, R.S.; Cook, C.N. Measuring progress in marine protection: A new set of metrics to evaluate the strength of marine protected area networks. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 219, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grorud-Colvert, K.; Sullivan-Stack, J.; Roberts, C.; Constant, V.; e Costa, B.H.; Pike, E.P.; Kingston, N.; Laffoley, D.; Sala, E.; Claudet, J.; et al. The MPA Guide: A framework to achieve global goals for the ocean. Science 2021, 373, eabf0861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, E.; Mayorga, J.; Bradley, D.; Cabral, R.B.; Atwood, T.B.; Auber, A.; Cheung, W.; Costello, C.; Ferretti, F.; Friedlander, A.M.; et al. Protecting the global ocean for biodiversity, food and climate. Nature 2021, 592, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, B.C.; Roberts, C.M. The Structuring Role of Marine Life in Open Ocean Habitat: Importance to International Policy. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gill, D.A.; Mascia, M.B.; Ahmadia, G.N.; Glew, L.; Lester, S.E.; Barnes, M.; Craigie, I.; Darling, E.S.; Free, C.M.; Geldmann, J.; et al. Capacity shortfalls hinder the performance of marine protected areas globally. Nature 2017, 543, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, J.C.; Dudley, N.; Hockings, M.; Holmes, G.; Laffoley, D.; Stolton, S.; Wells, S.; Wenzel, L. Guidelines for Applying the IUCN Protected Area Management Categories to Marine Protected Areas; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2019; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, S.; Ray, G.C.; Gjerde, K.M.; White, A.T.; Muthiga, N.; Creel, J.E.B.; Causey, B.D.; McCormick-Ray, J.; Salm, R.; Gubbay, S.; et al. Building the future of MPAs—Lessons from history: Building the Future of MPAs. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2016, 26, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friedlander, A.M.; Gaymer, C.F. Progress, opportunities and challenges for marine conservation in the Pacific Islands. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2020, 31, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimal, R.; Navarro, L.M.; Jones, Y.; Wolf, F.; Le Moguédec, G.; Réjou-Méchain, M. The global distribution of protected areas management strategies and their complementarity for biodiversity conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 256, 109014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoll, R.; Day, J.C. Correct application of the IUCN protected area management categories to the CCAMLR Convention Area. Mar. Policy 2017, 77, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, N. Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008; ISBN 978-2-8317-1086-0. [Google Scholar]

- e Costa, B.H.; Claudet, J.; Franco, G.; Erzini, K.; Caro, A.; Gonçalves, E.J. A regulation-based classification system for Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). Mar. Policy 2016, 72, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine Conservation Institute Blue Parks Award. Marine Conservation Institute 2020. Available online: https://marine-conservation.org/blueparks/ (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- IUCN Green List of Protected and Conserved Areas. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/theme/protected-areas/our-work/iucn-green-list-protected-and-conserved-areas (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Assis, J.; Failler, P.; Fragkopoulou, E.; Abecasis, D.; Touron-Gardic, G.; Regalla, A.; Sidina, E.; Dinis, H.; Serrao, E.A. Potential Biodiversity Connectivity in the Network of Marine Protected Areas in Western Africa. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, J.T.; Levin, L.A.; Carson, R.T. Incorporating ecosystem services into environmental management of deep-seabed mining. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2017, 137, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. 1994. Available online: https://treaties.un.org/Pages/showDetails.aspx?objid=0800000280043ad5 (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- FAO. UNFSA Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 Relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gjerde, K.M.; Yadav, S.S. Polycentricity and Regional Ocean Governance: Implications for the Emerging UN Agreement on Marine Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, D.C.; Jablonicky, C.; Crespo, G.O.; McCauley, D.J.; Kroodsma, D.A.; Boerder, K.; Gjerde, K.M.; Halpin, P.N. Empowering high seas governance with satellite vessel tracking data. Fish Fish. 2018, 19, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blanchard, C. Fragmentation in high seas fisheries: Preliminary reflections on a global oceans governance approach. Mar. Policy 2017, 84, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanning, L.; Mahon, R. Governance of the Global Ocean Commons: Hopelessly Fragmented or Fixable? Coast. Manag. 2020, 48, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. International Legally Binding Instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction; A/res/72/249; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gjerde, K.M.; Clark, N.A.; Harden-Davies, H.R. Building a Platform for the Future: The Relationship of the Expected New Agreement for Marine Biodiversity in Areas beyond National Jurisdiction and the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Ocean Yearb. Online 2019, 33, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CCAMLR. The Convention on the Conservation of Marine Living Resources; CCAMLR: Hobart, Australia, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- CCAMLR. Report of the CCAMLR Workshop on Marine Protected Areas; CCAMLR: Hobart, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Protocol (Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty Protocol). 1991. Available online: https://www.ats.aq/e/protocol.html (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals. 1972. Available online: https://www.ats.aq/e/related.html (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- CCAMLR. Conservation Measure 91-Protection of the South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf; CCAMLR: Hobart, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- CCAMLR. Conservation Measure 24-01. The Application of Conservation Measures to Scientific Research; CCAMLR: Hobart, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- CCAMLR. Conservation Measure 91-04. General Framework for the Establishment of CCAMLR Marine Protected Areas; CCAMLR: Hobart, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- CCAMLR. Conservation Measure 91-05, Ross Sea Region Marine Protected Area; CCAMLR: Hobart, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, C.M.; Bloom, E.; Kavanagh, A.; Nocito, E.S.; Watters, G.M.; Weller, J. The Ross Sea, Antarctica: A highly protected MPA in international waters. Mar. Policy 2021, 134, 104795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCAMLR. Conservation Measure 91-02, Protection of the Values of ASPAs and ASMAs; CCAMLR: Hobart, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- CCAMLR. Report of the XXXVI Meeting of the Commission; CCAMLR: Hobart, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Trathan, P.N.; Grant, S.M. The South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf Marine Protected Area. In Marine Protected Areas; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainley, D.; Brooks, C. Workshop Report and Synthesis: United States Research and Monitoring in Support of the Ross Sea Region Marine Protected Area; CCAMLR: Hobart, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- CCAMLR. Report of the Thirty-Eighth Meeting of the Commission; CCAMLR: Hobart, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Petersson, M.T. Transparency in global fisheries governance: The role of non-governmental organizations. Mar. Policy 2020, 104128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCAMLR. Conservation Measure 22-06, Bottom Fishing in the Convention Area; CCAMLR: Hobart, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, K. (Ed.) Global Commons and the Law of the Sea; Maritime Cooperation in East Asia; Brill Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands; Boston, NJ, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-90-04-37332-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, L. (Ed.) International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL). In Business, Human Rights, and Sustainability Sourcebook; ABA Book Publishing: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015; p. 1230. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, A.H.; Peck, L.S.; Aldridge, D.C. Ship traffic connects Antarctica’s fragile coasts to worldwide ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2110303118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedo, P.; Benayas, J.; Cajiao, D.; Leung, Y.-F.; De Filippo, D.; Liggett, D. What are the real environmental impacts of Antarctic tourism? Unveiling their importance through a comprehensive meta-analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 308, 114634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuth, M.A.; Wagner, A.M.; Sodhi, D.S.; Blaisdell, G.; Shelton, C. Ship Offload Infrastructure in McMurdo Station, Antarctica. In Proceedings of the ISCORD American Society of Civil Engineers, Anchorage, AK, USA, 2–5 June 2013; pp. 540–551. [Google Scholar]

- Bastmeijer, K.; Roura, R. Chapter 9. Environmental Impact Assessment in Antarctica. In Theory and Practice of Transboundary Environmental Impact Assessment; Brill Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 175–219. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN-WCC. Resolution #066—Guidance to Identify Industrial Fishing Incompatible with Protected Areas; IUCN-WCC: Marseille, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IAATO Tourism Statistics. Available online: https://iaato.org/information-resources/data-statistics/visitor-statistics/ (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- IAATO. IAATO Overview of Antarctic Tourism: A Historical Review of Growth, the 2020–21 Season, and Preliminary Estimates for 2021-22 2021; IAATO: South Kingston, RI, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- IAATO Vessel Directory. Available online: https://iaato.org/who-we-are/vessel-directory/ (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Sánchez, R.A.; Roura, R. Supervision of Antarctic Shipborne Tourism: A Pending Issue? In Tourism in Antarctica: A Multidisciplinary View of New Activities Carried Out on the White Continent; Schillat, M., Jensen, M., Vereda, M., Sánchez, R.A., Roura, R., Eds.; SpringerBriefs in Geography; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 41–63. ISBN 978-3-319-39914-0. [Google Scholar]

- CCAMLR. Report of the XXXVII Meeting of the Commission; CCAMLR: Hobart, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Roura, R.M.; Steenhuisen, F.; Bastmeijer, K. The shore is the limit: Marine spatial protection in Antarctica under Annex V of the Environmental Protocol to the Antarctic Treaty. Polar J. 2018, 8, 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roura, R. Antarctic Tourism and New Momentum for Expanding Marine Protection in the Southern Ocean; Linking Tourism & Conservation: Lysaker, Norway, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- CCAMLR Cooperation with Others|CCAMLR. Available online: https://www.ccamlr.org/en/organisation/cooperation-others (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- CCAMLR Publications|CCAMLR. Available online: https://www.ccamlr.org/en/publications/publications (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- CCAMLR Scientific Committee|CCAMLR. Available online: https://www.ccamlr.org/en/science/scientific-committee (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Home Page|CCAMLR. Available online: https://www.ccamlr.org/ (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- Lutchman, I.; Thomas, H.L. The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Re-sources (CCAMLR) in the Southern Ocean: Case Study Summary Report; European Commission: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane, T. Maori Associations with the Antarctic; University of Canterbury: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wehi, P.M.; Scott, N.J.; Beckwith, J.; Rodgers, R.P.; Gillies, T.; Van Uitregt, V.; Watene, K. A short scan of Māori journeys to Antarctica. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehi, P.M.; van Uitregt, V.; Scott, N.J.; Gillies, T.; Beckwith, J.; Rodgers, R.P.; Watene, K. Transforming Antarctic management and policy with an Indigenous Māori lens. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 1055–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annex V to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty-Area Protection and Management 2002. Available online: https://www.ecolex.org/details/treaty/annex-v-to-the-protocol-on-environmental-protection-to-the-antarctic-treaty-area-protection-and-management-tre-148102/ (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Giakoumi, S.; McGowan, J.; Mills, M.; Beger, M.; Bustamante, R.H.; Charles, A.; Christie, P.; Fox, M.; Garcia-Borboroglu, P.; Gelcich, S.; et al. Revisiting “Success” and “Failure” of Marine Protect-ed Areas: A Conservation Scientist Perspective. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordonnery, L.; Kriwoken, L. Advocating a Larger Role for Environmental Nongovernment Organizations in Developing a Network for Marine Protected Areas in the Southern Ocean. Ocean Dev. Int. Law 2015, 46, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C.M.; Crowder, L.B.; Osterblom, H.; Strong, A.L. Reaching consensus for conserving the global commons: The case of the Ross Sea, Antarctica. Conserv. Lett. 2019, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SC-CCAMLR. Report of the Thirty-Ninth Meeting of The Scientific Committee; CCAMLR: Hobart, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Capurro, A. The Fragile Antarctic Peninsula: Conserving Biodiversity through Marine Protected Areas; Latin America’s Environmental Policies in Global Perspective; Wilson Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Teschke, K.; Brtnik, P.; Hain, S.; Herata, H.; Liebschner, A.; Pehlke, H.; Brey, T. Planning marine protected areas under the CCAMLR regime—The case of the Weddell Sea (Antarctica). Mar. Policy 2021, 124, 104370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IWC. Chairman’s Report of the Forty-Fourth Meeting, Appendix 4: Resolution on a Sanctuary in the Southern Hemisphere; International Whaling Commission: Cambridge, England, 1993; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Vierros, M.K.; Harden-Davies, H. Capacity building and technology transfer for improving governance of marine areas both beyond and within national jurisdiction. Mar. Policy 2020, 122, 104158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, A.; Jones, P.J. Protecting the ‘blue heart of the planet’: Strengthening the governance framework for marine protected areas beyond national jurisdiction. Mar. Policy 2021, 127, 104260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.A. Institutional arrangements for the new BBNJ agreement: Moving beyond global, regional, and hybrid. Mar. Policy 2020, 122, 104143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putin, V. Press Statements Following Russian-Argentine Talks. Available online: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67706 (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- Hassanali, K.; Mahon, R. Encouraging proactive governance of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction through Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). Mar. Policy 2022, 136, 104932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, K.; Gruby, R.L. Polycentric Systems of Governance: A Theoretical Model for the Commons. Policy Stud. J. 2019, 47, 927–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yadav, S.S.; Gjerde, K.M. The ocean, climate change and resilience: Making ocean areas beyond national jurisdiction more resilient to climate change and other anthropogenic activities. Mar. Policy 2020, 122, 104184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MPA Name and Zone | Conservation Objective(s) | IUCN (2019) Category | MPA Guide Level of Protection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ross Sea General Protection Zone | “To conserve natural ecological structure, dynamics and function throughout the Ross Sea region at all levels of biological organization, by protecting habitats that are important to native mammals, birds, fishes and invertebrates” (CCAMLR, 2016, p. 3) | 1A: Strictly Protected Area | Highly Protected |

| Krill Research Zone | Objective of the GPZ and additionally “to promote research and scientific understanding of krill, including in the Krill Research Zone in the northwestern Ross Sea region” (CCAMLR, 2016, p. 3) | IV: Habitat/Species Management | Lightly Protected |

| Special Research Zone | Objective of the GPZ and additionally “to provide reference areas for monitoring natural variability and long-term change, and in particular a Special Research Zone, in which fishing is limited to better gauge the ecosystem effects of climate change and fishing, to provide other opportunities for better understanding the Antarctic marine ecosystem and to underpin the Antarctic toothfish stock assessment by contributing to a robust tagging program, and to improve understanding of toothfish distribution and movement within the Ross Sea region” (CCAMLR, 2016, p. 3) | IV: Habitat/Species Management Area | Lightly Protected |

| South Orkney Islands | “Protection of representative examples of pelagic marine ecosystems, biodiversity and habitats; Protection of representative examples of benthic marine ecosystems, biodiversity and habitats; Protection of critical life history stages for penguins; Protection of key ecosystem processes associated with the southern shelf region” (Delegation of the EU to CCAMLR, 2014, pp. 4–6) | 1A: Strictly Protected Area | Highly Protected |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nocito, E.S.; Sullivan-Stack, J.; Pike, E.P.; Gjerde, K.M.; Brooks, C.M. Applying Marine Protected Area Frameworks to Areas beyond National Jurisdiction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5971. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105971

Nocito ES, Sullivan-Stack J, Pike EP, Gjerde KM, Brooks CM. Applying Marine Protected Area Frameworks to Areas beyond National Jurisdiction. Sustainability. 2022; 14(10):5971. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105971

Chicago/Turabian StyleNocito, Emily S., Jenna Sullivan-Stack, Elizabeth P. Pike, Kristina M. Gjerde, and Cassandra M. Brooks. 2022. "Applying Marine Protected Area Frameworks to Areas beyond National Jurisdiction" Sustainability 14, no. 10: 5971. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105971

APA StyleNocito, E. S., Sullivan-Stack, J., Pike, E. P., Gjerde, K. M., & Brooks, C. M. (2022). Applying Marine Protected Area Frameworks to Areas beyond National Jurisdiction. Sustainability, 14(10), 5971. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105971