Abstract

(1) The use of heritage in fieldwork, enabling the analysis of historical sources in museums via school trips, contributes towards the development of historical thinking and the formation of active, participative and critical citizens within the field of formal education (2) The general objective of the present study is to estimate the value which teachers and museum educators confer upon museums and school visits in the stages of early years, primary and secondary education. The research method employed is quantitative, based on the study of a descriptive comparative cross-sectional survey. The participants are 442 teachers, who visited two archaeological museums with their class groups in order to carry out an activity relating to the subject of history, and 18 museum educators. The data collection tool was the MUSELA © questionnaire. (3) The main results indicate that both teachers and educators agree that it is the responsibility of the educator to connect the visit with the interests of the group. 70% of the museum educators are totally in agreement with the academic perspective provided by museums, and more than 75% of the teachers and museum educators are totally in agreement with the fact that the objective of museum visits is to increase knowledge and cultural experience. (4) Educational agents’ understanding of the use of visits to archaeological museums as field trips for history work is a challenge that must be confronted over the coming decade. It is necessary to promote a model of collaboration that develops interaction by generating common educational projects.

1. The Development of Historical Thinking among Pupils and the Value of Museums

A world without historical perspective and critical thinking is a world few would enjoy [1].

Study plans for the social sciences increasingly advocate for an approach to history which incorporates into its educational methodology the use of historical method. This approach to the teaching and learning process of history encourages critical creative thinking and the development of the skills of historical thinking on the part of the learner.

A study carried out by [2] Lucas & Estepa (2016), in which 82 secondary pupils and nine social sciences teachers were interviewed, showed that heritage elements are considered to be a key educational tool in history classes in terms of contributing towards the development of critical thinking and acquiring an active and committed attitude towards one’s environment.

According to Ross & Gautreaux (2018) [3], critical thinking is considered to be an essential element of “civic competence”; the capacity people have to handle persistent and complex social problems (p. 383).

The learning of history (via the scientific or historical method) will, in some way, have an impact on both creative [4] and historical thinking [5].

Henley (2012, cited in [4]) states that history makes it possible to improve creativity regarding past time and one of its advantages is the sense of place and identity it generates among pupils, the appreciation of the context in which they live. Visiting museums could lead children to gain a deeper understanding of the world which surrounds them and provide new perspectives in their studies. The visits museum is considered to be a vital element in all stages of education.

The main reason for this line of work is the conviction that in order to know history pupils cannot develop a learning process based on memorising of facts, dates and events (historical contents), which are at times disconnected and decontextualised for the learners [6,7]. Pupils must acquire a more complex process of historical thinking and must construct their own knowledge of history based on the strategies and procedures offered by the scientific method, employing research strategies in their surroundings and thinking historically [1,8,9,10,11,12].

The key methodological focus for teaching students to think historically, to develop historical thinking, is on the use of historical method. Via this approach, the student is forced to rely on sources and historical evidence which will make it possible to gather information, interpret it, contrast his/her starting hypotheses and build his/her own historical explanations and, thus, achieve knowledge of history (substantive content) based on the strategic contents using the six concepts or key competences as the means of application [5,13]: Historical significance, evidence, continuity and change, cause and consequence, historical perspectives, and the ethical dimension.

Ultimately, in order to develop historical thinking and to work with these six key concepts, the student must be capable of argumentation based on work carried out with historical sources. VanSledright (2014) [7], in an effort to overcome the traditional approach to history teaching based on substantive knowledge and to delve into strategic knowledge, advocates the application of historical method in history classes, employing work with historical sources as a strategy.

In this regard, museums emerge as essential educational agents in the development of historical thinking. Along the same lines, Prats & Santacana [14] highlight the great value of working with historical sources for the learning of history. They carried out a review on historical sources and stressed the importance of employing archaeological remains, monuments and museums in the classroom as sources of the past. Visits to museums and other heritage sites are perceived as an educational resource which implies direct knowledge of reality that it is not possible to observe, analyse and understand inside the classroom. The activities which are generally prepared in school as the result of a coherent educational activity form part of a direct and explicit approach to educational programming and are normally the result of great professional experience [14].

Kratz & Merritt (2011) [15] maintain that museums are a model of transformation of the traditional learning environment of the classroom, and are capable of fostering the skills which all students should develop in the 21st century [16]: critical thinking and collaboration; information synthesis; application of learning in real life; innovation and creativity and teamwork.

In this context, heritage education has become one of the scientific disciplines which has grown most in recent years, generating one of the lines of research regarding the use of non-formal educational spaces, contributing towards learning strategies which foster the formation of an active, participative and critical citizenship within the field of formal education [17].

The prime responsibility of a museum is to satisfy the needs of its visitors [18]. Dana (1917) [19], considered to be a legend among museum educators in the United States, was one of the first documented precursors of education in museums (with his work The New Museum). Attempting to adapt museums to the needs of the community, he reflected on the educational work carried out in museums, relating it to different factors, not only to guided visits. The word education is used almost exclusively to refer to formal education provided by a teacher, with a textbook, in a group or course and with its corresponding evaluation. If educational work in museums were considered only in this strict sense, it would not be possible to include the selection of objects, their arrangement and display, the methods of installation, labels, catalogues, texts, information sheets, guides, carers, curators [19]. He offers among his fundamental notes for the transformation of the museum:

- The schools have definitive aims and pursue them, and all the people in their youth are compelled to feel their influence. The museum can reach only those who it can attract. This fact alone is enough to compel it to be convenient to all, wide in its scope, varied in its activities, hospitable in its manner and eager to follow any lead the humblest inquirer may give.

- Get good museum workers; let one of them at least be experienced in teaching; find a space for display; get an insect, (…) a plaster cast, a spinning wheel, a tea cup, a bit of rock, a mineral, a dozen of the things made commercially in your community, a typewriter, an appropriation for printing, a friend in the local newspaper, set your museum brains at work upon these objects, and, in a few weeks you can open a museum which every intelligent person will rejoice to see (p. 39).

The educational function of museums, going beyond their cultural and conservational role, historically began to form part of museological discourse around the 1970s, when the International Council of Museums (ICOM) redefined the definition of ‘museum’ to include its educational role: “El museo es una institución sin fines de lucro abierta al público y al servicio de la sociedad, que adquiere, conserva, investiga, comunica y exhibe, con el propósito de educación y deleite, los testimonios materiales del hombre y su medio” [20] (p. 30) [The museums is non-profit institutions open to the public and at the service of society, which acquire, conserve, research, communicate, and exhibit the material evidence of mankind and its context for the purpose of education and enjoyment].

From that time onwards, Education Departments began to be established internationally in order to design, coordinate and plan different types of actions in an attempt to satisfy the needs of all sectors of the public. The parameters of education and cultural action were developed from cultural actions linked from the community, in line with Dewey’s (1989) [21] pedagogical principles.

Education Departments have the necessary human, economic and material resources to guarantee the development of the necessary actions for responding to the requirements which the community demand of the museum. This can be achieved via projects, the supervision of exhibitions, the coordination of programmes, the creation of educational material, the development of activities, etc.

The 21st century ushered in a process of cultural democratisation, in which the main underlying actions are to make museums more user-friendly and accessible to all audiences. However, in spite of the fact that, in the English-speaking context, the role of Education Departments was reconfigured with the aim of guaranteeing a response to cultural and social changes, readapting their actions to a new society, in Spain, Education Departments continue to be considered of secondary importance in museums, linked with a lack of professionalisation among their workers. Museums in Spain, then, continue a line based on exhibitions which attract large numbers of visitors. Only some museums develop quality educational actions and programmes which are adapted to the new necessities of society [22].

Museums are important places for creating synergies and links between non-formal and informal education and the community. The 21st-century museum is an open space for society in which it is necessary to create solid experiences with the participation of associations, schools, foundations, cultural centres, universities, etc., and to ensure that the museum collaborates with its territory, neighbourhood, surrounding area, community, etc.

Socially responsible museums enable citizens to acquire critical consciousness. They are places which, in the 21st century, far removed from their traditional functions of documentation, preservation, research and dissemination, have the aim of fostering their social dimension and the value which society confers upon heritage. So much so that the network of museums which depends on the Spanish Secretariat of State for Culture (SEC) has carried out an action focused on its social aspect and the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport (MECD) has dedicated resources, time and effort to the socialisation of museums.

But are the museums a didactic resource adhered to in educational reality that implies direct knowledge of the reality that, within the walls of the classrooms, it is not possible to observe, analyze and, therefore, learnd? Do visits to museums contribute to the use of sources in the classroom? In Spain, the research which has been carried out in this field has determined what it is that pupils learn in the development of historical thinking (study of the curriculum and textbooks) and in what way this learning is assessed (analysis of exams and assessment tests) [23]. The results of these studies have confirmed the existence of an educational model of history based on conceptual contents, with a lack of procedural or second order contents which make it possible for students to develop work with sources and the use of historical method. On the basis of this prior research, the present study seeks to estimate the value given by teachers and museum educators to museums and school visits in the stages of early years, primary and secondary education for the process of the teaching and learning of history. In order to achieve this, an attempt will be made to understand the importance of museums as places for the development of teaching and learning processes based on cultural heritage and the variables which influence the application of this teaching model based on citizen participation within non-formal educational contexts (archaeological museums). These variables focus on the degree of responsibility of museum educators, the concept of museum and the objective of school visits to museums.

1.1. Learning in Museums

Throughout the 20th century, in the context of the English-speaking world, attempts were made to study the educational value of museums and learning possibilities in the field of formal education. In the United States, research was carried out to analyse the educational value of field trips to museums. This study arose due to the lack of evidence on the effects of field trips to museums among students. Promoted by some of the most significant American institutions (Hoover Institution at Stanford University, Harvard Kennedy School and Thomas B. Fordham Institute), it is considered to be the first large-scale randomised-control trial designed to measure what students learn from field trips to art museums [24]. The study was carried out at the Crystal Bridges of American Art Museum (Arkansas). The information was collected from a guided tour of the museum undertaken by a total of 525 school groups (38,347 students) from early years education up to 12th grade, organised into a control group and an experimental group. A structured questionnaire was administered to 10,912 students and 489 teachers from 123 different schools over three weeks of visits to the museum. The results of the research showed that following the field trip to the museum: students recalled a great deal of information regarding what they had seen and discussed; substantial improvements were made in their knowledge and capacity to think critically about art; the students experienced an increase in historical empathy and showed higher levels of tolerance; they were more likely to visit cultural institutions such as art museums in the future; and their taste for art and culture increased. Thus, it can be stated that field trips to art museums can be a significant opportunity for learning. The authors reached the conclusion that art can be considered to be an independent tool for the effective teaching of history in the classroom. Institutions, schools and teachers should be aware of the need to include field trips to museums in curricular frameworks and in teaching programmes in order to promote cultural enrichment and the learning of history.

These assumptions are defended and promoted by the Academy for Global Citizenship, a Public Charter School in Chicago. This school has a programme in which students must spend 25% of the school timetable outside of the school carrying out activities in the surrounding area. The aim is to learn through contact with the environment and with real life. Learning is promoted based on the environment, experimentation and the reality in which, and upon which, learning takes place [25].

Chen (2007) [26] made a comparison between lifelong education, museum education and school education based on the assumption that both museum education and school education are part of lifelong education. Table 1 shows the comparison which concerns us here between museum education and school education: museum education contains the patterns of non-formal and informal education. Unlike museum education, school education presents a formal pattern of education, in which planned learning and assessment are obligatory. Teachers must fulfil the guidelines defined by the curriculum and pupils are expected to adhere to the norms of school education.

Table 1.

The comparative characters among museum education and school education.

1.2. The Degree of Responsibility of Educational Agents

1.2.1. Educational Agents in Museums

Educational agents are understood to be all those who mediate, plan, develop and supervise the activities carried out with students in the course of the field trip to the museum and what is to be learned from it. In this case, such individuals include the museum educators, members of the museums’ Education Departments (ED), who are responsible for designing and adapting activities aimed at formal, non-formal and informal education. On the other hand, there are the guides, specialists who attempt to show the content of the museum via a tour and to carry out the activities proposed by the ED (they are also occasionally responsible for planning the activities). Last but not least are the teachers, who must plan the activities proposed by the museum or adapt them to the interests of their groups and evaluate the learning achieved via the activities.

According to De Camilloni (1996) [27], in this sense, the museum, an enclosed space, is visited by people with a peculiar relationship, which is defined, with a certain degree of randomness, in an idiosyncratic way as a dialogue with an interlocutor who can be both absent and present through the objects.

Prats & Santacana (2011) [14] stress the importance of collective work and of the potential presented by museums for this work to be carried out, not only by the students, but also by the collaborative efforts of the museums’ education teams and the teachers. Alderoqui (1996) [28] had previously stressed the need for joint collaboration, considering museums and schools to be partners in education. Both teachers and guides should join forces in order to achieve the most important objective: the educational exploitation of the visit, involving the motivation and interests of the students, the characteristics of the group, the desired educational aims and the development of skills.

For this reason, from the beginning, when receiving school visits, it is extremely important that the two agents involved have fluent communication and define beforehand both the characteristics and interests of the group and the aim of the visit. In this regard, Huerta & Ribera [29] mention the responsibility both agents should have: it is the teachers who decide to visit the museums with their pupils, who are aware of the reality, needs and expectations which their group of students can take advantage of when they visit an exhibition. On the other hand, museums, through their education staff, should get to know their visitors in order to programme the educational function of the visit, and schools, through their teachers, should also know the museum which they are visiting for the same purpose.

Prats & Santacana (2011) [14] assume that school visits should result from coherent planning on the part of teachers, based on pedagogical activity and should appear directly and explicitly in the teaching programme. In order to achieve the established requirements, planning both prior to and after the visit must be carried out. This planning should be made by the ED or, if it does not provide material and/or pre-planned activities, by teachers in collaboration with, or at the least in communication with, the staff of the ED. This will make it possible to ensure that the minimal conditions are put in place for the activity in the museum to be carried out.

Due to these factors, it is necessary to take into account the agents who intervene in this framework of action. According to [30], the first people who work together in this collaboration are museum educators and teachers. The educators interviewed in the five places of the museum considered that their role was to serve as a link between schools and museums.

1.2.2. The Role of the Teacher Regarding the Use of Museums

Hannon & Randolph (1999) [30] carried out a study which attempted to study the collaboration established between museum educators and teachers based on their associations, the curriculum and students’ learning. Within this study, they determined the people who collaborate in this relationship between museums and schools and their roles. According to the authors, teachers are an indispensable part of this collaboration between museums and schools. The results proposed by the museum educators stated that teachers have several types of responsibility in the effort to collaborate in the museum experience:

- To communicate the curricular objectives to the museum educators so that they can be adapted to the educational requirements and the students’ needs in order to improve the visit.

- To prepare the visit to the museum beforehand with their students by carrying out appropriate activities.

- To evaluate the students’ learning in the museum through the visit.

Therefore, teachers must be responsible for the educational exploitation of the field trip to the museum. This implies designing and communicating objectives and criteria, developing activities and evaluating learning.

Teachers who are aware of and have a preference for the integration of museums and their resources within the teaching programme guarantee that their students learn with a higher level of motivation. Thus, teachers should help their students to broaden their horizons and contribute so that the teaching and learning process can be developed in close proximity to society and the real lives of their students [26]. According to Chen, the teacher’s functions in the collaboration between museums and schools are:

- To play the role of facilitator in order to obtain direct and effective communication with the students.

- To control the quality of their students’ learning.

- To broaden the sphere of museum-school collaboration.

- To create new models of collaboration.

In conclusion, as indicated by Alderoqui [31] visits “arranged” between schools and museums must establish the responsibility and leading role of the teachers which is different to the cultural consumption of the services offered by museums. Teachers adopt a linking role between the museum and the school, as do the museum educators.

1.2.3. The Role of the Museum Educator Regarding School Visits

According to Fontal (2003) [32], the heritage educator is the professional responsible for establishing connections between heritage and society, an intermediary in the teaching and learning processes in cultural heritage. The heritage educator is seen as being responsible for managing education and cultural heritage and his/her responsibilities include:

- Communicating with their audience and learning in a reciprocal manner.

- Detecting the qualities, necessities, conditions, social, political and cultural features of the collective or individual audience.

- Creating teaching material.

- Actively participating with teachers in the design of their programming.

Ref [32] states that heritage managers are conceived as somewhere between technicians specialised in the research and conservation of heritage, such as historians, archaeologists or restorers, and technicians of education, communication and dissemination, such as educators, entertainers and guides.

In the context of this study, the role of heritage manager is somewhat misleading, as it is necessary to focus on the roles of museum educators and guides. However, this conception is essential and is one of the aims to be achieved within heritage education.

The collaboration between museums and schools is represented as two sides of the same coin: on the one side is the teacher and on the other the museum educator. According to Hannon & Randolph (1999) [30], three primary connections stand out for these agents to assume their responsibility:

- To connect the museum and the school population.

- To link the students’ understanding of physical (heritage) objects with abstract concepts (the content which is the objective of the learning).

- To relate the real-world experiences provided by the museum with the subject matter studied by the students at school.

Therefore, museum educators are responsible for connecting the visit with the interests of the students, whilst serving as a link between the museum and the school. This conception of the educator as a link is seen as a mediator between the resources of the museum (heritage objects, historical sources) and abstract concepts (that is, with the contents and competences which the students should learn and develop), as an intermediary between the experiences provided by the museum and the teaching and learning process.

Museums, via their educational programmes, should satisfy the learning needs of their visitors. However, as [26] maintains, the vision presented by museum educators concerning visitors’ needs is limited and they are not familiarised with the practical realities of the school curriculum.

1.2.4. The Responsibility for Teaching in Museum-School Collaboration

According to Liu (2002, cited in [26]), the research carried out has demonstrated that the direct participation of the teacher is the key to ensuring the success of museum-school collaboration. Therefore, teachers play a crucial role in guaranteeing that such collaboration is carried out.

This high level of responsibility is conferred upon them due to the fact that one of the problems is that a collaboration model based on guided tours paying close attention to the museum educator (with the teacher occupying a passive role) does not guarantee that the field trip will be appropriate for different schools, classes and students.

Ref [26] maintains that, in order to guarantee learning, it is essential that teachers prepare the visit beforehand with a teaching plan which enables the students to understand the experience of the museum visit and the tasks which are to be carried out based on the visit.

The results of a study carried out by Liao (2005, cited in [26]), showed that teachers play the role of facilitators in museum-school collaboration and are considered to be a dynamic basic resource and promotors of the quality of learning of their students. According to this function, teachers can:

- Plan active collaboration projects between museums and schools.

- Support the educational activities of museums with real action in the teaching and learning process in the classroom.

The collaboration between museums and schools is aimed at students’ learning. Therefore, the teacher is responsible for planning and evaluating their learning. As a consequence, teachers are, naturally, the best communicators between schools and museums and are those best able to control the quality of learning in terms of museum-school collaboration [26].

The same author highlighted the capacity of influence that teachers may have on their students: if one teacher influences thirty or forty students, the influence of the students multiplies, increasing rapidly as more teachers join [26].

In summary, the premise must be assumed that, in order to be able to develop learning in museums and to use museums and heritage objects as an educational source and resource, it is necessary for there to be fluid communication between the agents involved; the design and development of pre-visit and post-visit activities and the use of heritage objects, their analysis or resources and materials that the museum may provide. In other words, it is necessary to advance towards this model of collaboration between schools and museums. However, in most cases this is not always true. This could be a future objective to be reached in the field of heritage education. As [33] state, heritage education in the context of formal education is lacking in the preparation of projects and the planning of teaching sequences via the use, study and appreciation of heritage.

1.3. Museums: Concept and Typologies

Until the 1980s, museums were considered to be elitist places in which no type of connection was established with society, be it via discourse, interests or the problems which were to be addressed. After that time, museums began to be aware of the need for change, to stop being merely containers of objects with no meaning. From this perspective, museums began to be considered as a means of communicating heritage. They came to be understood as places in which heritage was to be preserved and disseminated, as a means or resource through which the population (school groups, cultural and endogenous tourism) could communicate with different forms of heritage. From that time on, the concept of heritage evolved to include any element or source which helps the population to understand the past and, therefore, our present. It diversified to encompass a broad range of areas in a multidisciplinary manner. The direction of heritage education changed its pretensions and it became established as a subject responsible for analysing and developing educational proposals, the investigative, transdisciplinary and socio-critical condition of which transfers values of identity to the population, developing intercultural respect and social change, thus forming a socially and culturally committed citizenship [34,35].

From the beginning of the 21st century, museums have gone from being mere containers of art destined for the elite to being considered as a sphere for the construction of learning. They are a means which provides the key to understanding facts or problematic areas, a generator of experiences, a space in which the features of identity which define a society are created, where feelings of belonging to historical, architectonic and cultural heritage are formed [36,37,38] pointed out that the changes taking place in museums, both in terms of their image and their transformation, turned these places into an efficient tool through which visitors could learn.

Nonetheless, the preconception of museums as being inaccessible and hostile still persists among the educational community. However, for others, they are seen as a social element through which a taste for art, culture and learning in non-formal places can be aroused. Perhaps this aspect is one of the greatest transformations to have taken place in museums, along with the progressive distancing of the image of being centres of erudition and progress towards the desired objective of creating more social museums [39].

1.3.1. The Concept of Museum

One of the most revealing definitions of museum is that given by De Camilloni (1996) in the prologue of Museos y Escuelas: socios para educar [28]: A museum is a special, extraordinary place. A different place, which is demarcated and separated from everyday life. A place full of treasures, in which decontextualised or recontextualised objects can be found out of an express will of building a dismantlable discourse which can be freely read by visitors.

Within museums, heritage, the legacy which a society considers to be the most relevant vestige for understanding its history, provides us with information on the social and historical events which have taken place throughout the time and space of a region or territory [40].

There can be no doubt that museums and, therefore, the museological space and the heritage contained therein, are an essential resource at all levels of education and in practically all areas and subjects of the curriculum.

Due to this social and cultural change, which has reshaped the vision of museums in the 21st century, museums are presented as containers of heritage objects with an educational potential capable of awakening, promoting, developing and strengthening the teaching and learning process carried out in schools today. Specifically, archaeological museums are seen to be fertile areas for developing different learning strategies in schools and among non-expert users through working with objects [41,42,43].

Calaf (2009) [44] considers that postmodern society needs heritage which draws near to the public as a whole, not only to those who are curious or studious. Such is her interest in this relationship between museums and schools that she directed one of the most innovative research projects in the field, attempting to analyse this relationship under the educational programmes of different museums with different heritage categories [45,46,47].

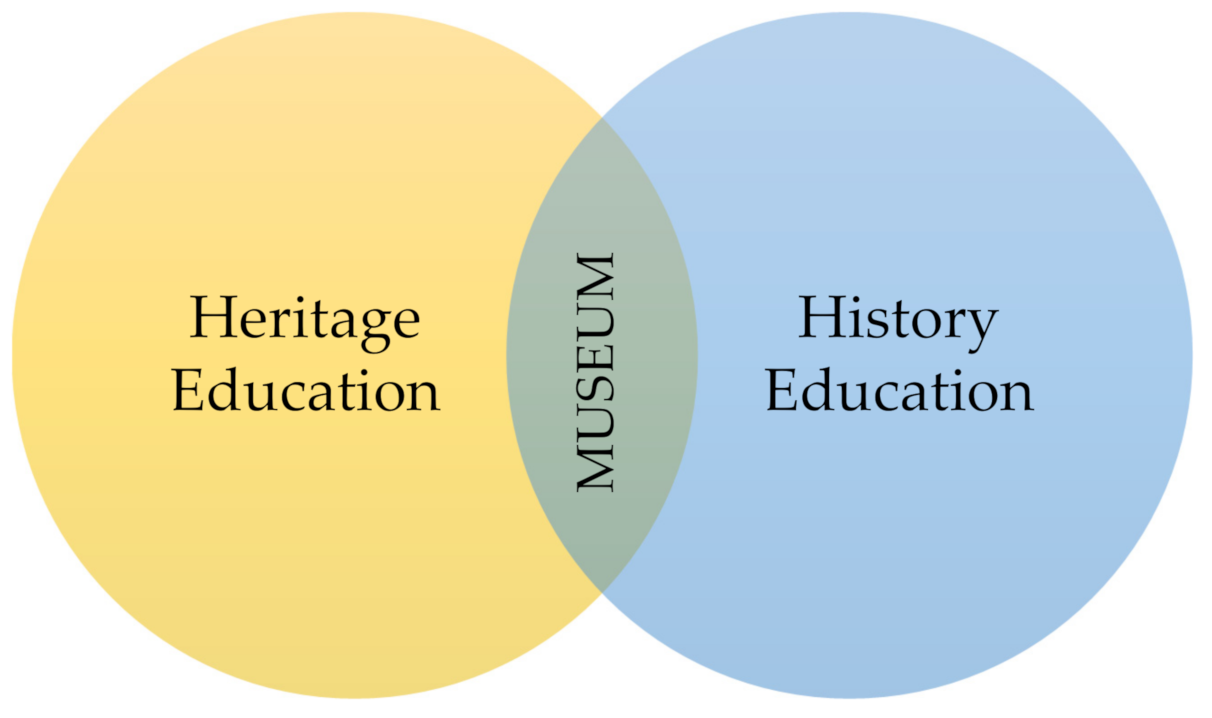

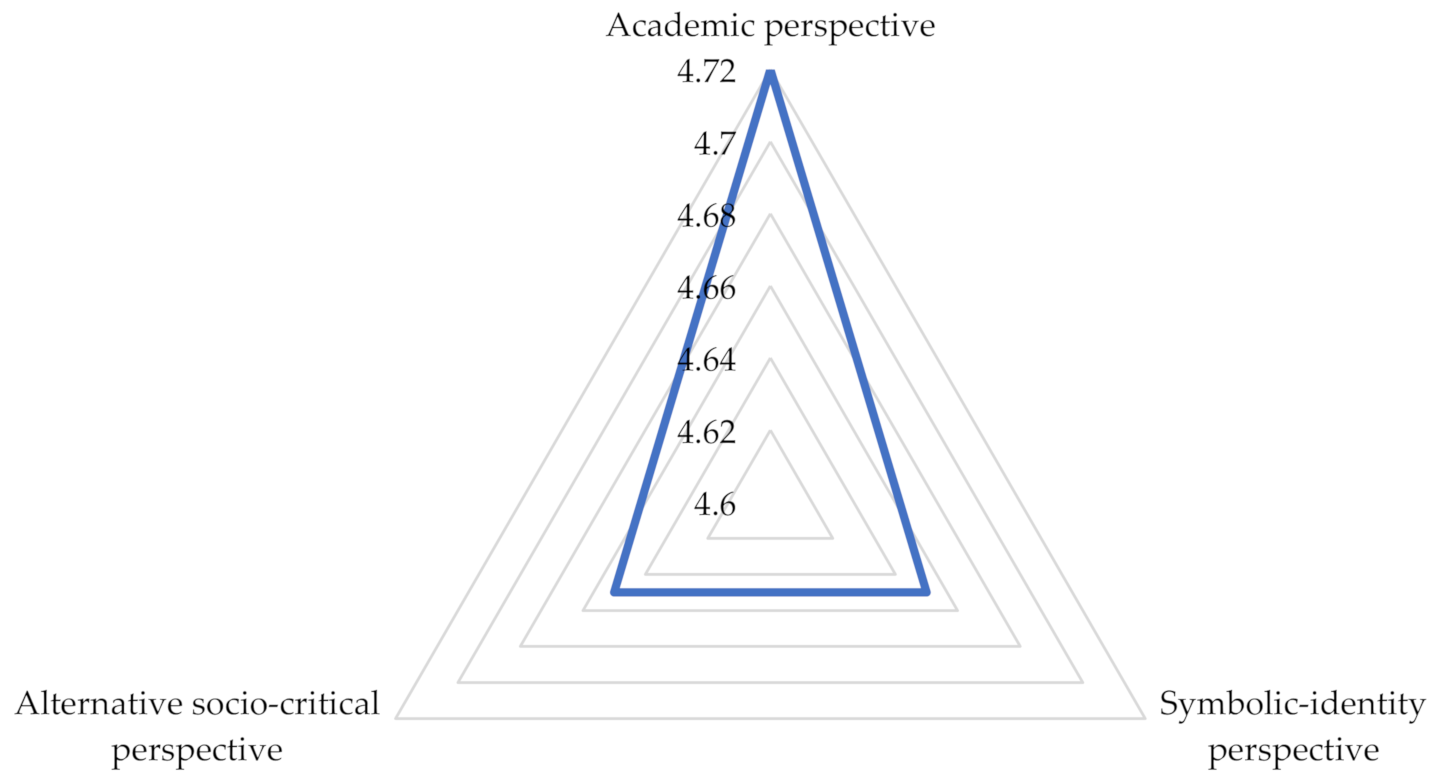

In this regard, museums, and the heritage assets contained within them, play an essential role in history education. As can be observed in Figure 1, museums are presented as the meeting point between history education, whose natural space is the classroom (formal education context) and heritage education, the non-formal educational context of which can be diverse (museums, archaeological sites, interpretation centres, galleries, exhibitions, etc.).

Figure 1.

The role of museums in the teaching and learning process of history and heritage. Source: Authors’ own work.

In museums, representative aspects of a specific age can be found, enabling us to travel in time and understand aspects of history, which is approached in an experiential way, extending beyond mere images. Museums are considered to be non-formal educational institutions [36] and must be viewed as a teaching resource and a means for the teaching of the social sciences: natural, artistic, historical, archaeological, material and immaterial elements of which heritage consists. They help to illustrate, approach and examine in depth the knowledge of their contents.

Ref [29] also defend the view of the role of museums and museological heritage as an essential resource in early years, primary and secondary education. The elements contained in museums are a record of historical memory as they transmit aspects and facts of different cultures progressively created with the passing of the centuries. Based on this premise, museums should become a useful tool which provides teachers with educational strategies used throughout their school programming and which fulfils educational functions. In order to achieve this, it is essential for there to be a common configuration of networks and skills for communication and education among the different museum complexes and schools in such a way that these spaces can form part of the school curriculum and fully perform their educational role.

Museums have progressively evolved to become true educational spaces. The demands on the educational community have led to museums becoming a work tool [48].

1.3.2. Typologies of Museum

Museums are considered to be non-formal educational institutions. Archaeological museums present educational possibilities, thus they are understood to be means of education. The term “means” is used as it is a concept which implies that there must be educational aims and certain objectives must be met.

This category is sustained by bringing together the classification of typologies of museums which currently co-exist (traditional, modern and postmodern) and their functions [49,50] with the educational possibilities which they present [36] and the objective of the process of communication of heritage [51].

According to De Camilloni [27], new proposals for participative museums were added to the old model of exhibitors of objects, in which objects are not only shown but also explained, experienced and demonstrated.

Juanola & Colomer [49] distinguish three types of museums which co-exist today:

- The traditional museum, the function of which is to transmit the contents of the museum to the public via its collection. It could be considered that this type of museum focuses on communicating and transmitting contents, be they artistic, historical, etc. [36]. In this type of museum, the objective and dissemination of heritage is aimed at the knowledge of facts and information of a cultural nature, illustrated and/or focused on anecdotal aspects [51]. This is what Martín Cáceres (2012) defends as the practical-conservationist objective of teaching, conferring an academic perspective upon heritage.

- The modern museum, in which educational value is a maxim within the museum’s discourse. Here, not only contents are transmitted, but also social aesthetic values regarding the conservation of heritage [36]. A perspective of symbolism and identity is conferred upon heritage [52]. This typology of museum is considered as a space in which respect and appreciation for heritage is transmitted, granting it a symbolic value capable of shaping identities [36].

- The postmodern museum opens up educational horizons. Its function is not merely to communicate and interpret heritage, but rather it has a social function and a critical purpose in terms of education and the dissemination of heritage [53]. It represents the social vision of heritage as a generator of social and civic values [54,55] and acquires an alternative socio-critical perspective of heritage [52].

Depending on the conception that teachers or museum educators have of museums, these can comply with one vision or another.

The way in which a school approaches field trips and school visits shows how teachers understand the study of the environment and also reveals their conception of the teaching and learning process [56].

1.4. The Purpose of School Visits to Museums

In general, a school visit to a museum (independently of its typology) can serve different aspects of education, depending on the importance attributed to the field trip by the teacher:

According to [50] and the presuppositions established in Spanish educational law [57] (Ley Orgánica 8/2013, de 9 de diciembre, para la Mejora de La Calidad Educativa, 2013) [Organic Law 8/2013 of 9 December, For the Improvement of Quality in Education], along with the hypothesis progress established by Martín (2012), school visits to museums (Table 2):

Table 2.

Conceptual analysis variables regarding the purpose of field trips in accordance with the educational paradigm.

- Increase students’ knowledge and cultural experiences.

- Enable students to develop the skills of the scientific method.

- Foster social participation among students via their projection in the environment.

As can be observed in Table 2, each of the variables correspond to an approach or, as Requena (2018) states, paradigmatic conceptions, distinguishing between the technocratic paradigm, the interpretive paradigm and the socio-critical paradigm [58,59].

As far as teaching planning is concerned, throughout the study, the different types of field trip established by Villarrasa [60,61,62] have been taken into account. Each type of trip presents a specific purpose. The main purposes are shown in Table 3, according to which a field trip to a museum can be framed in classroom teaching planning.

Table 3.

Conceptual analysis variables regarding the educational purpose of school visits to museums.

Rivero and Feliu [63] state that when we visit museums or archaeological sites a contextualisation is necessary in order to understand them. Without understanding, the sequence of procedures for heritage education [32] is broken in the background. Understanding our past, knowing how civilizations lived in the past, discovering what they ate, how they related to each other, our common interests among people and history, and therefore archaeology, generates curiosity. However, in order to be able to understand the past in all of its complexity, we need educational tools to bring us closer to it.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Defining the Hypotheses

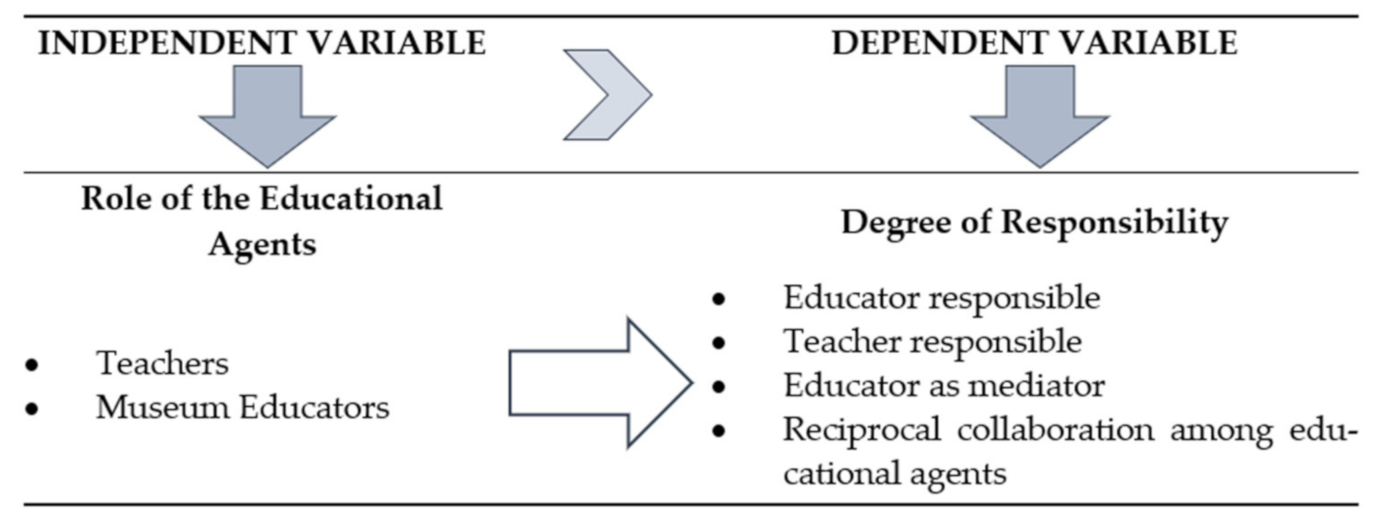

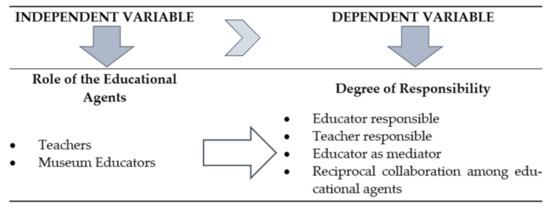

This study analyses the differences in the evaluation of the degree of responsibility of educational agents in school visits to museums (dependent variable or criterion) and the role of educational agents (teachers and museum educators) (independent variable or predictor) was analysed.

Hypothesis 1.

There are significant differences in the evaluation of teachers and educators regarding the degree of responsibility of educational agents in school visits to museums.

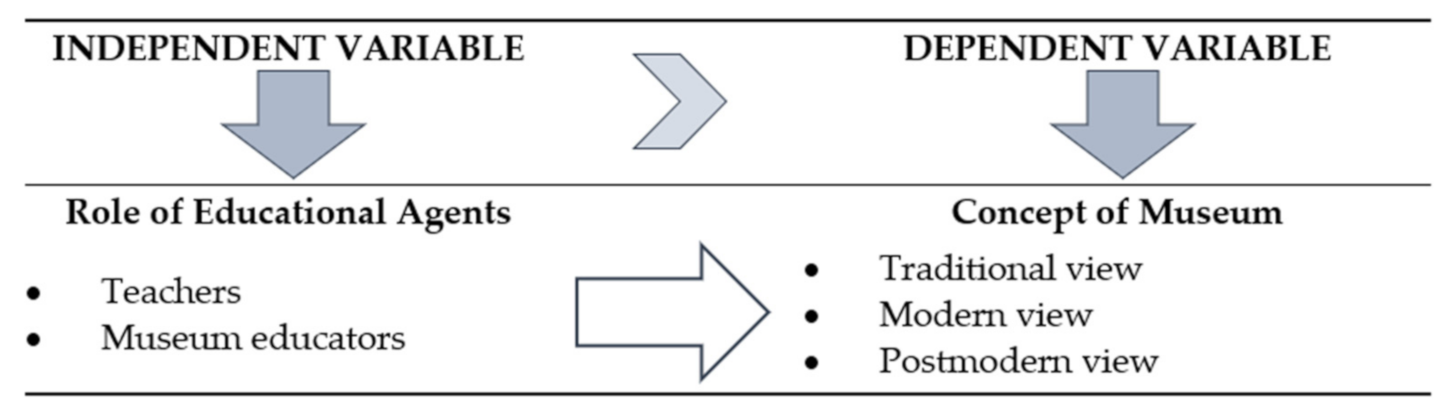

The conceptions (dependent variable or criterion) of teachers and museum educators (independent variable or predictor) regarding museums were also compared.

Hypothesis 2.

Teachers’ conceptions regarding museums are different to those of museum educators.

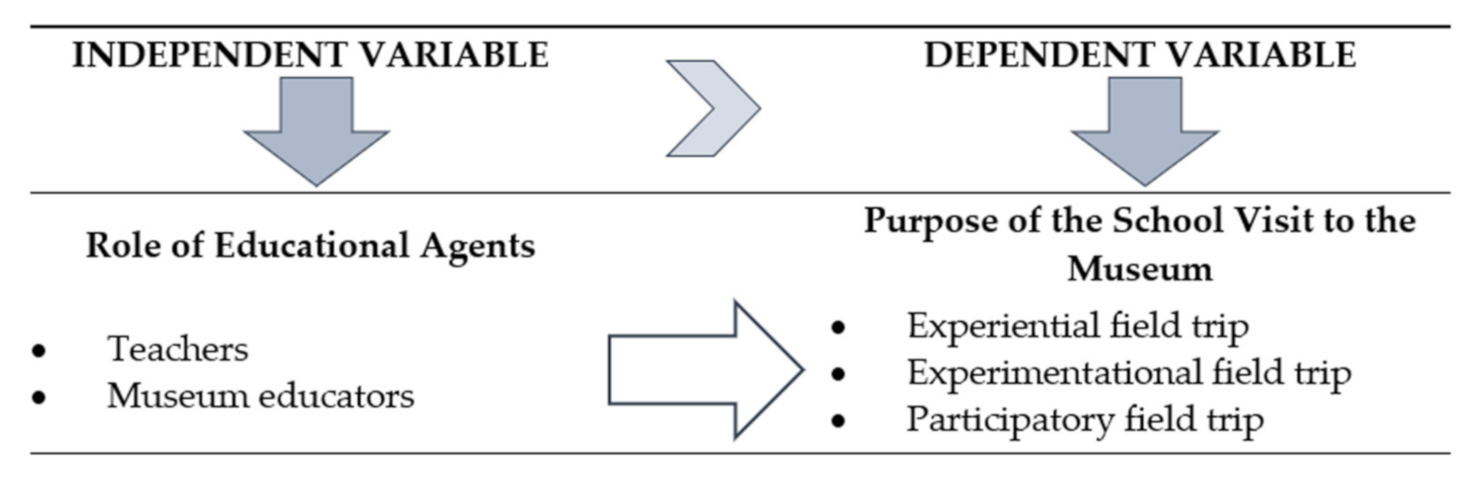

Furthermore, the study examines the differences between the evaluation of the usefulness of school visits (dependent variable or criterion) of teachers and museum educators (independent variable or predictor).

Hypothesis 3.

The evaluations of teachers and educators differ significantly regarding the usefulness of school visits to museums.

2.2. Approach and Design

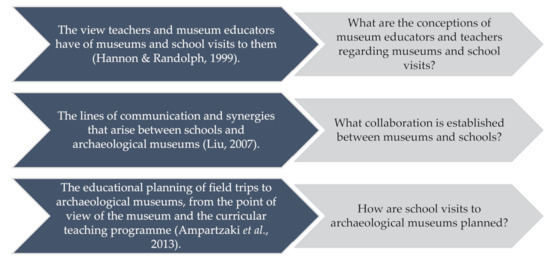

A research design with a quantitative approach was chosen in order to respond to the problems and objectives posed (Table 4). A cross-cutting survey was employed with a descriptive-comparative purpose. The study is focused on a descriptive phase in which quantitative information is handled based on questionnaires administered to teachers and museum educators with the aim of attempting to understand the opinion of educational agents (teachers and museum educators) regarding museums and school visits to them.

Table 4.

Research objectives and analysis variables according to methodological function in the design of the research.

Specifically, answers are sought to the following research questions: What degree of responsibility is attributed to educational agents according to museum educators and teachers? Which vision of museums is closest to the opinion of museum educators and teachers? What do the educational agents consider to be the purpose of school visits to museums?

2.3. Context and Participants

This research is set in the context of two archaeological museums which, due to their size, organization, heritage typology, capacity and audience, have common characteristics and constitute an ideal space for the learning of history in the stages of early years education, primary education and compulsory secondary education.

More specifically, the two archaeological museums are located in Spain, in the Autonomous Community of the Region of Murcia (MU) and the province of Alicante (MA). In spite of the fact that one is provincial and the other is controlled by the Autonomous Community in question, both museums are similar in terms of size, the amount of heritage they accommodate, typology, etc. However, there are also notable differences, MA has a permanent professional team of five staff in the museum, who form the Department of Education and Dissemination.

In order to guarantee anonymity, the exact name of each museum has not been used. Below, we shall present some of the most relevant characteristics of both contexts.

2.3.1. The Archaeological Museum Located in Murcia (MU)

The MU is a state-owned institution, the management of which has been transferred to the Autonomous Community of the Region of Murcia. It has been located in the old Palacio Provincial de Archivos, Bibliotecas y Museos since its re-opening in 2007. It has made a great effort to develop its role as an educator and disseminator of heritage.

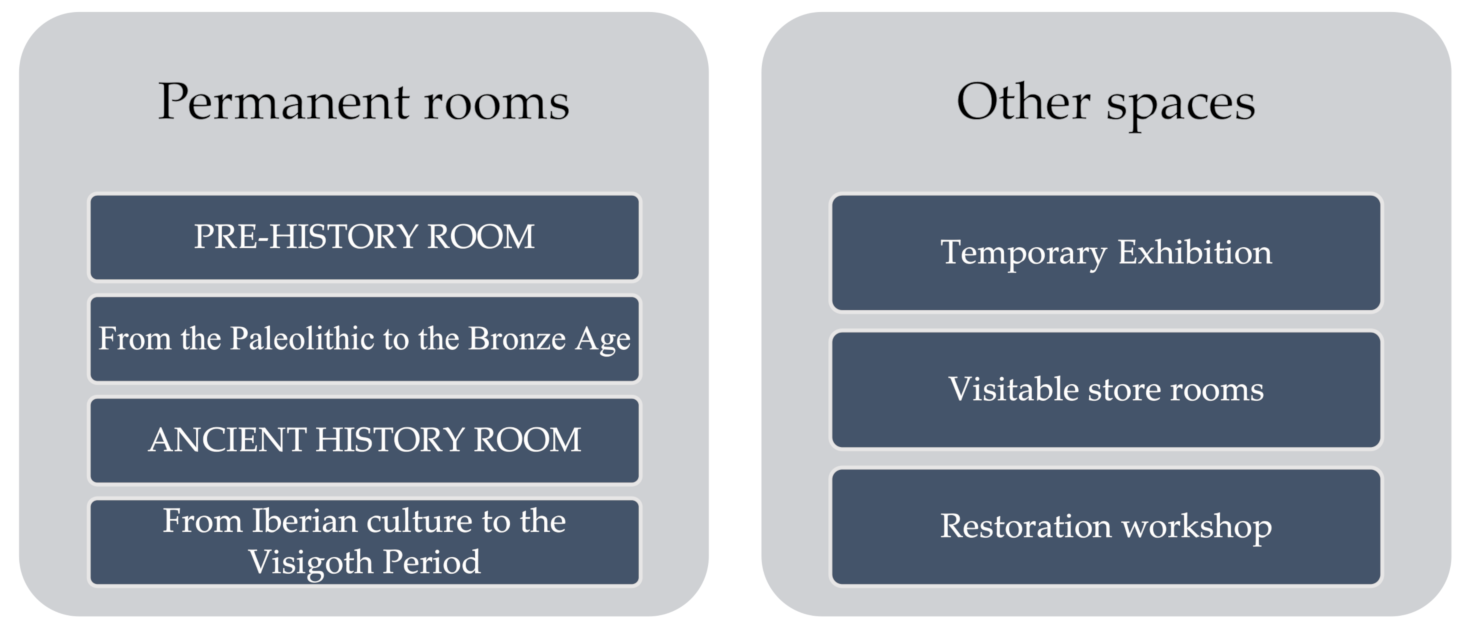

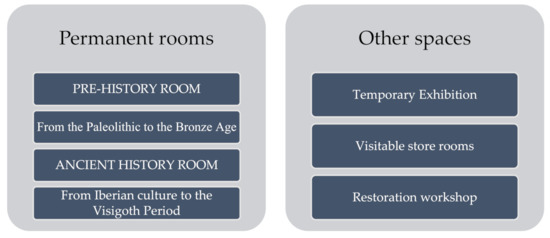

The permanent collection of the museum proposes a stroll through Pre-history, from the Palaeolithic to the Bronze Age, continuing through Ancient History up to the Visigoth Period. Its discourse is based on three main aspects: types of habitats, the evolution of technology and funeral rites (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Spatial organisation of the Murcia museum. Source: Authors’ own work.

2.3.2. The Archaeological Museum Located in Alicante (MA)

The MA is a facility whose competences and legal status are structured and managed by two large institutions. The archaeological museum (created in 1932) depends administratively on the Provincial Government of Alicante and the Foundation of the Valencian Community. It was set up in 2001 at a time of great momentum when the location of the museum was changed, adopting its place in the architectonic complex of the old San Juan de Dios Provincial Hospital, which was inaugurated in 2002.

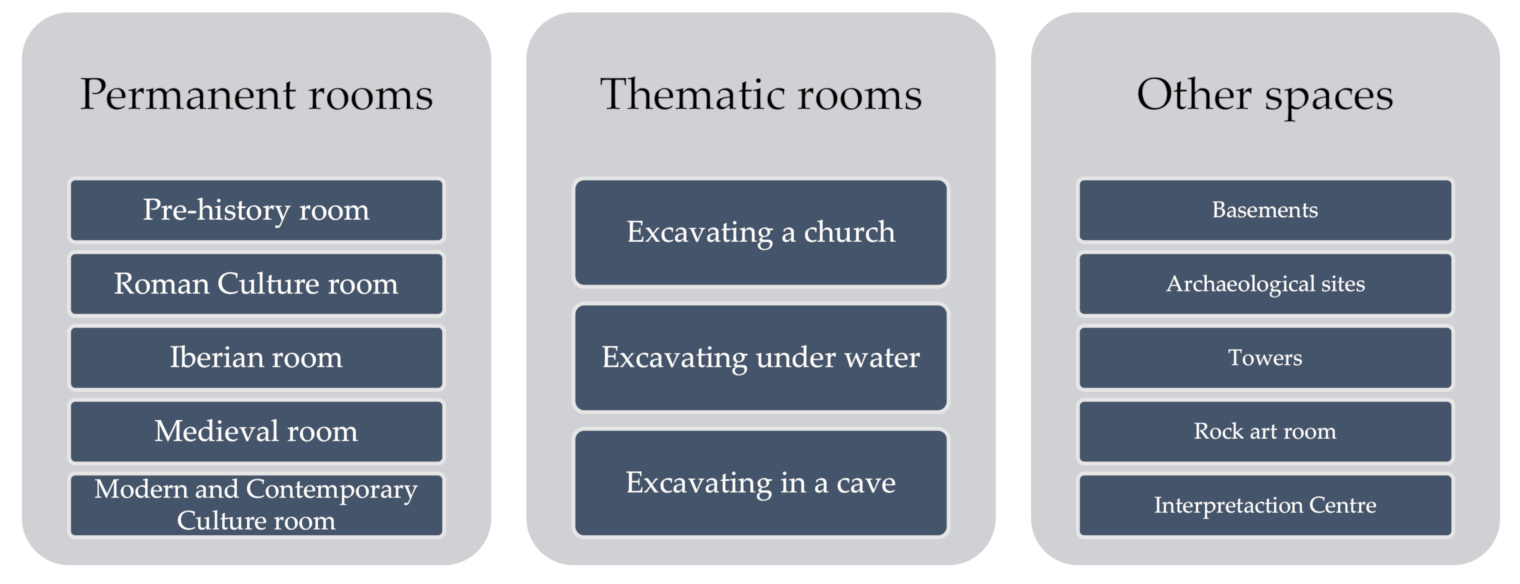

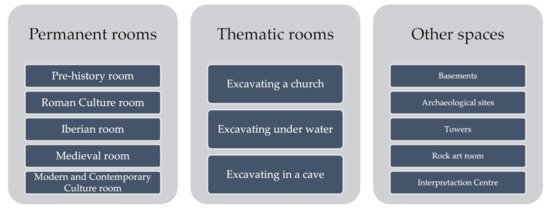

After occupying its new premises, from 2002, its educational and innovative discourse runs through each of the rooms and installations of the museum. As a result of this, it became necessary to create a permanent team dedicated to dissemination and education in the museum. In 2005, the museum’s Department of Education and Dissemination was formed.

The museum consists of five permanent rooms, three thematic rooms, three rooms which are used for temporary exhibitions and the basements. Different archaeological and monumental sites also lie under the management of the MA (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Spatial organisation of the Alicante museum. Source: Authors’ own work.

2.3.3. Participants in the Research

The sampling technique used for the selection of the participants was a mixed procedure (cluster sampling). The participating subjects were the cultural managers (museum educators, guides and the education managers of both museums) and early years, primary education, and compulsory secondary education teachers who, throughout 2017 and 2018, visited the archaeological museums with their class groups in order to carry out a visit, guided tour, workshop or any other activity in the museum.

The participating teachers of the MU (n = 160) and the MA (n = 272) present an average age of around 43. Their average experience in the teaching profession is 17 years.

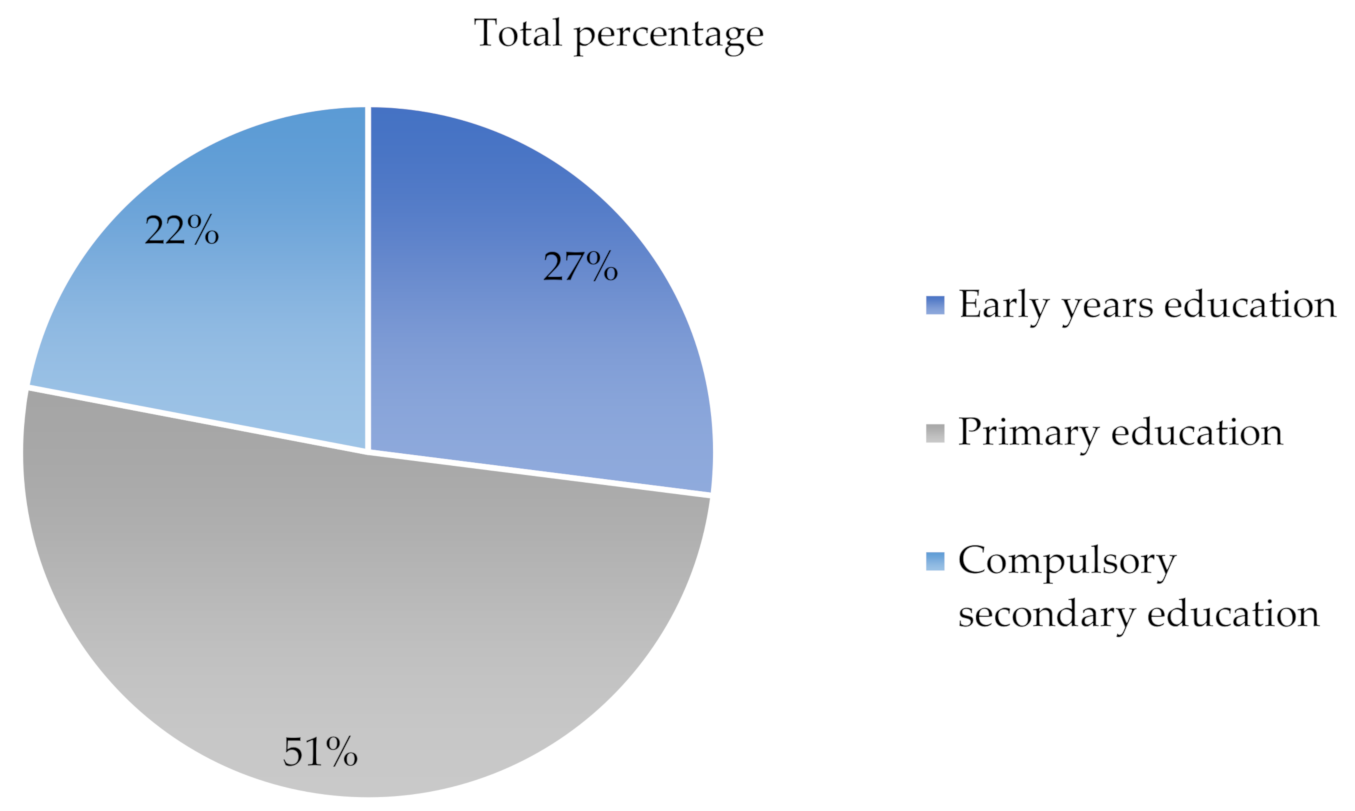

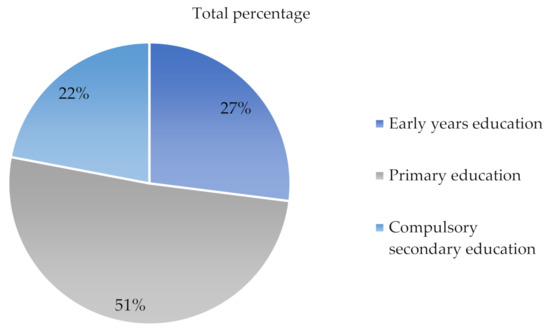

The school groups which visited the museums most were from primary education (50.8%), followed by early years groups (27.6%). The fewest number of visits were those corresponding to the stage of compulsory secondary education, representing 21.6% of the total (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Total percentage of school groups visiting the archaeological museums according to their educational stage. Source: Authors’ own work.

The average age of the educators was 36 years of age, with an average professional experience of eight years. Of the total of educators surveyed (n = 18), when differentiated according to museum (nMU = 4; nMA = 14), the average teaching experience does not fluctuate. Although the educational staff of the MU are significantly fewer and are not hired by the museum, but are subcontracted via an external company, they are permanent workers of the museum and have an average professional experience of 8.5 years. On the other hand, the group of educators of the MA have less average experience (8.21 years). Most educators from the MA, those responsible for carrying out guided tours, workshops, and other activities with school children, are not hired directly by the museum but are subcontracted from an external company and most of them have temporary contracts. The permanent staff of the museum have an average professional experience of more than ten years.

2.4. Survey Structure

The tool used for the data collection was the MUSELA © questionnaire in its two versions, aimed at teachers (MUSELA DO) and museum educators (MUSELA EDU), elaborated ad hoc and validated via a study which was both exploratory and confirmatory [64].

The aim of both tools is to analyse the relationship and lines of collaboration which are established between museums and schools and to verify whether archaeological museums are useful tools which offer educational strategies to teachers to be used in their planning in the teaching of the social sciences in general and history in particular.

The construction process of the questionnaires was forged from the main theoretical principles regarding the educational potential of museums [35,36,65,66]), the importance of the educational agents who intervene in the interaction between heritage and education [31], models of collaboration which are established between museums and schools [67] and the need for sequential planning of school visits to museums [14,33,68].

The research design employed for the construction and validation of the MUSELA © questionnaires is based on the Classical Test of Theory (CTT). The second version was submitted to the expert judgement procedure with the aim of analysing the degree of agreement between the value judgments emitted by the participants of the group of external judges. The Kendall’s W coefficient of concordance has made it possible to verify that there is agreement among the judges who intervened in the validation process of the MUSELA © tool by way of the scale designed for this purpose. Furthermore, the internal consistency and validity of the construct of the MUSELA questionnaires was analysed via pilot and confirmatory studies. The analysis of the reliability of the pilot tool aimed at teachers via the Cronbach’s alpha model (total scale and two halves), both for the items as a whole and for the grouping of the items by dimensions, reveals that the scale is appropriate. The analysis of the main components reduces the 38 variables to seven factors which explain almost 99% of the total variance. The MUSELA EDU © validation process (in the pilot study) has led to substantial improvements in the tool, in addition to verifying its reliability. The results of the statistical tests indicate that the MUSELA EDU © tool has improved in terms of internal consistency, reaching a value of two points higher than the tool in its pilot study (σ = 0.896). Moreover, in spite of the fact that the variance explained in the definitive tool is lower, it presents a high degree of variability (100% in the pilot study, σ = 0.65 and 94.59% in the confirmatory study, σ = 0.90).

The final version of the study presents a body of questions organised into five blocks: general information, the teacher’s or educator’s opinion regarding museums and school visits, the collaboration between schools and archaeological museums, planning visits to archaeological museums and the overall evaluation of the visits to the archaeological museums. The MUSELA DO © questionnaire consists of 27 questions and the MUSELA EDU © of 24 questions.

The questionnaire was self-administered by each participant individually. It was delivered in person to teachers visiting the participating archaeological museums with their groups of students in order to be answered throughout the duration of the school visit. The questionnaire was also given to the educators of these museums. As Moroy, González-Geraldo and Hernández-Pina [69] point out, the aim is for the participants to return the questionnaire answered in full. Thus, the way in which the questionnaires were administered implied a great cost in terms of their distribution and collection.

The study focuses on the data collected from the section on planning the field trip to the archaeological museum, specifically on those variables which make reference to the design, development and follow-up of the museum visit by the educational agents during the school visit (dichotomous, ordinal scale, various response options and multi-response). The questions of the questionnaire which have been taken into account for this study can be observed in Appendix A (the variables used by the teachers) and Appendix B (the variables which gather the information from the museum educators).

2.5. Procedure for the Collection, Handling and Analysis of the Data

After the data was collected, data matrices were elaborated using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences IBM ® SPSS (version 24). After executing the program and creating the data matrices, these were explored and the operativised data were systematised into different variables both according to their nature or measurement scale and their methodological function in the objectives and hypothesis of this research.

The analytical techniques were systematised according to the purpose for which they had been applied: descriptive statistics, mean, standard deviation and quartiles including the cross tables or contingency tables. Graphic techniques were used as analytical strategies and were developed with the statistical program IBM ® SPSS for Windows (version 24) and with Microsoft Excel for Mac (version 16.24).

In order to contrast the hypotheses, non-parametric tests for two independent samples were used to compare ranges (Mann-Whitney U test). For all of these cases, bilateral statistical significance tests were used, assuming 0.05 as the level of significance or critical level.

3. Results

In order to understand teachers’ and archaeological museum educators’ conceptions regarding museums and school visits, the results obtained in each of the objectives proposed were collected from the perspective of museum educators and teachers in different analysis variables.

3.1. The Role of Educational Agents: Degree of Responsibility

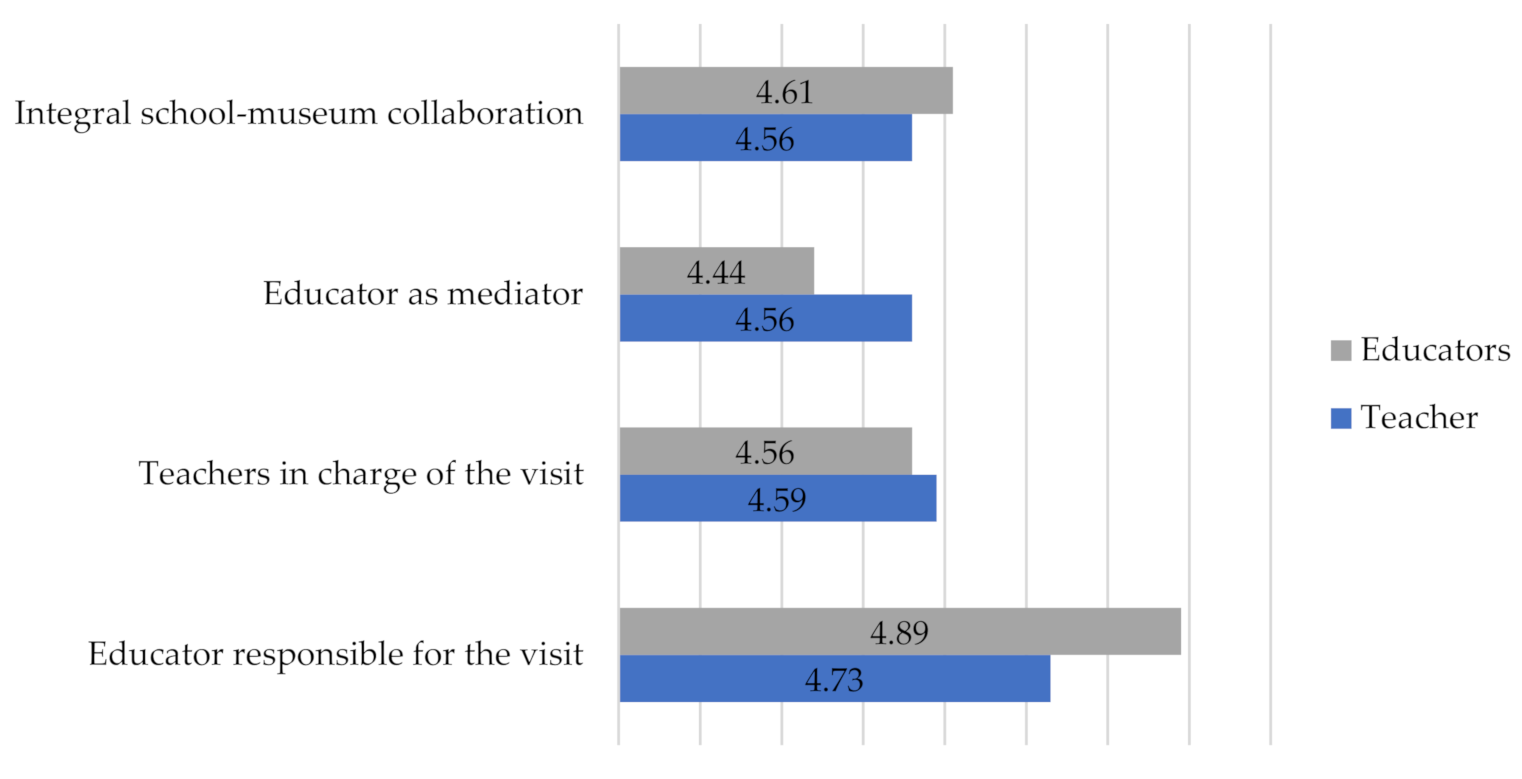

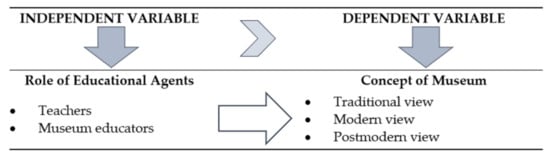

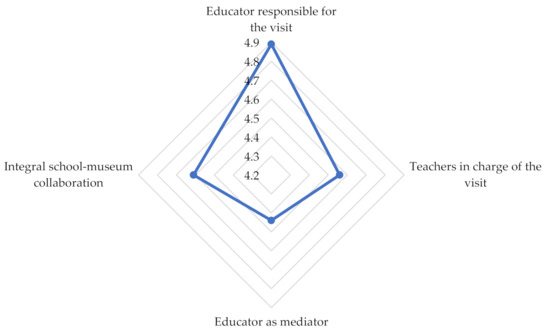

The first objective is to determine the degree of responsibility which educational agents consider should be attributed to them during school visits to museums. In the design adopted, the independent variable is defined as the role of the educational agent, with two levels (teachers and museum educators) and the dependent variable as their degree of responsibility. The latter variable has been divided into four indicators (Figure 5):

Figure 5.

Variables which intervene in the achievement of objective 1 of the research. Source: Authors’ own work.

- The museum educator should connect the visit with the interests of the group.

- Teachers should be responsible for the educational exploitation of the field trip.

- Museum educators should serve as a link between the museum and the school.

- Joint collaboration between teachers and museum educators is necessary.

3.1.1. The Museum Educator Should Connect the Visit with the Interests of the Group

As can be observed in Table 5, both teachers and educators award a mean value higher than 4.5 in relation to the responsibility of the educator in connecting the visit with the interests of the group.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of the analysis indicators for objective 1 of the research.

According to the Q1value, more than 75% of the educational agents awarded a score of five. In other words, they are totally in agreement in terms of the responsibility of the educator in the school visit.

21.70% of the teachers are in agreement and 76.2% totally in agreement with the view that the educator is considered to be responsible for the visit ( = 4.73; . On the other hand, the educators exceed the mean score of the teachers regarding this variable, with only 11.1% being in agreement compared with 88.9% who are totally in agreement.

3.1.2. Teachers Should Be Responsible for the Educational Exploitation of the Field Trip

As far as the opinion that teachers are responsible for the educational exploitation of the field trip is concerned, the mean scores awarded by the educational agents are reduced by 0.14 from the point of view of the teachers ( = 4.59; , and by 0.33 for the educators ( = 4.56; .

However, Q2 shows that more than 50% of the teachers and educators award a score of five. 27% of teachers are in agreement with their responsibility, whereas 67% are totally in agreement. The museum educators offer a similar, albeit fluctuating, evaluation. More than three out of ten educators are in agreement that it is the responsibility of the teachers, six out of ten are totally in agreement and only one educator neither agreed nor disagreed with this view.

3.1.3. Museum Educators Should Serve as a Link between the Museum and the School

The indicator stating that educators should be considered as mediators was awarded a mean score of 4.56 out of 5 by teachers, while the average score awarded by educators in agreement with the view that they should be considered as a link between schools and museums was lower ( = 4.44; .

The quartile values indicate that more than 50% of the teachers and educators are totally in agreement with the view that educators should be considered as mediators. Specifically, if the mean percentages are taken into account, 63.5% of teachers are totally in agreement with this responsibility, awarding a score of five, compared to 61.1% of the educators. 30% of teachers agree and 6% neither agree nor disagree. On the other hand, almost three out of ten educators (27.8%) agree and one in ten (5.6%) disagree or neither agree nor disagree (5.6%).

3.1.4. Reciprocal Collaboration among Educational Agents

As for the view that collaboration is necessary with those responsible for education in museums, the mean score of teachers ( = 4.56; and educators ( = 4.61; indicates that both are in agreement with this need. As can be observed in Table 5, educators are 0.05 points above the mean score of teachers. The mean scores show that both teachers and educators are in agreement in terms of the responsibility and role to be played by educational agents in a school field trip.

The first quartile indicates that 25% of educators and teachers award a score lower than 4, whereas more than 50% scored this aspect higher than 4. However, the evaluations of teachers and educators vary in a few proportions: more than six out of ten teachers are totally in agreement with the need for joint collaboration among educational agents and 27.8% are agreement. Seven out of ten educators are totally in agreement and standard deviation.

Almost three out of ten are in agreement with the need for joint collaboration.

The contrasting of hypotheses via the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test for two independent variables leads to the acceptance of the null hypothesis, which indicates that there are no statistically significant differences in the view presented by museum educators and teachers regarding the degree of responsibility which educational agents attribute to school visits to museums (p > 0.05).

3.2. Concept of Museum

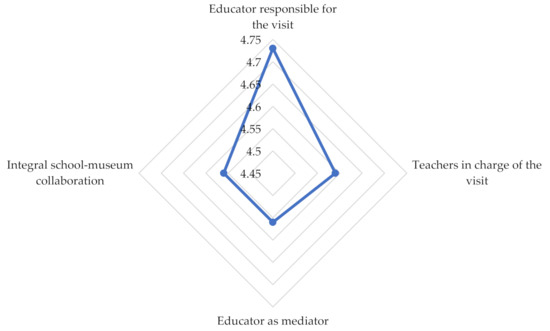

The second objective is to identify the degree of the conception regarding museums from the point of view of the educational agents. The view of the educational agents regarding museums is defined as the dependent variable, with the independent variable being the role of the educational agent in two levels (teacher and museum educator).

The dependent variable (Figure 6) is divided into three indicators:

Figure 6.

Variables which intervene in the achievement of objective two of the research. Source: Authors’ own work.

- Museums contain primary sources which transmit historical knowledge.

- Museums are places in which symbolic and identity values are transmitted.

- Museums are resources for the development of a critical and responsible citizenship.

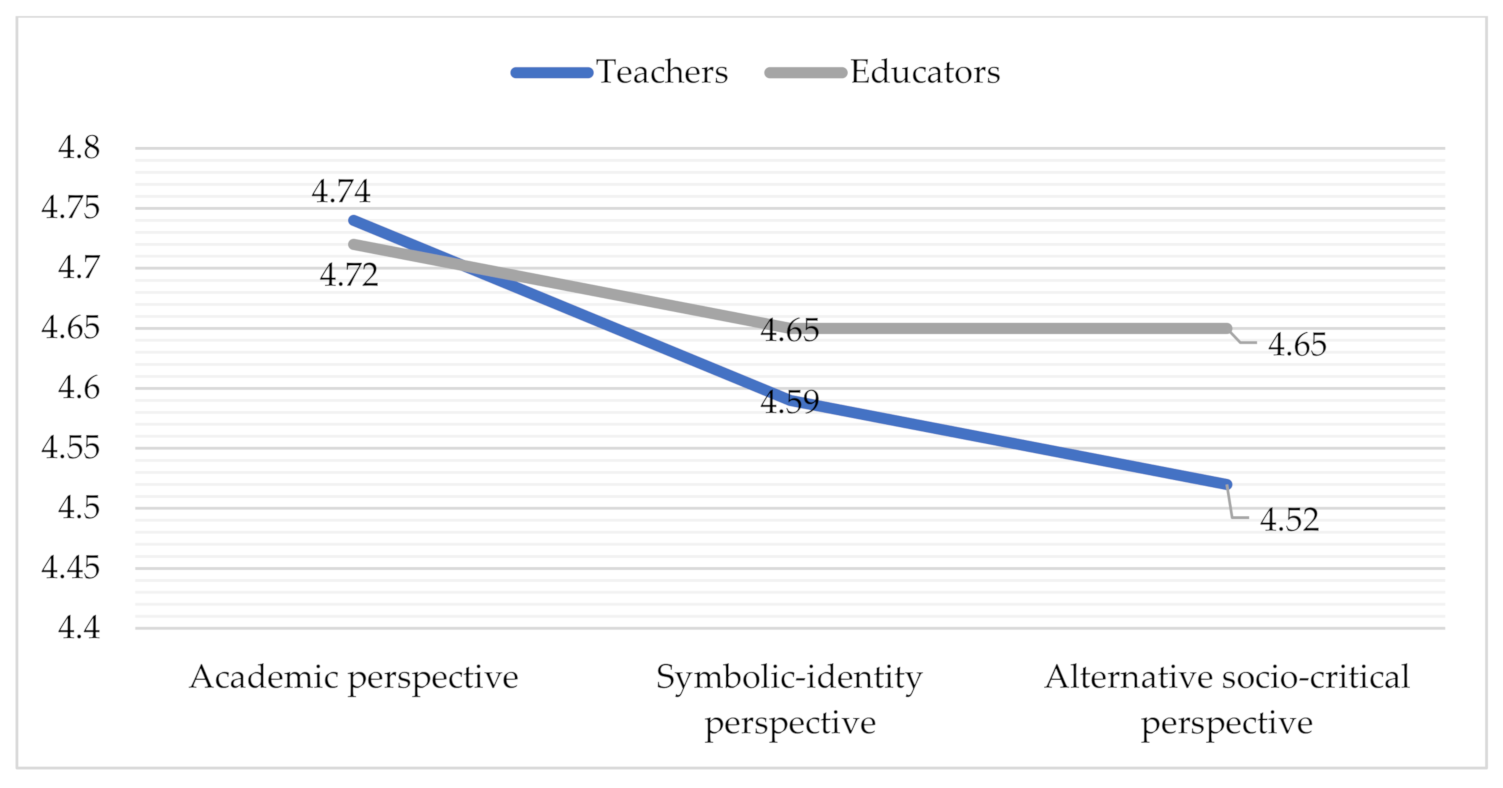

Each of the variables corresponds to a typology or view of museums (traditional, modern and postmodern) and an educational perspective of museums (academic, symbolic-identity and alternative socio-critical heritage, respectively) concepts taken from [52,70].

3.2.1. Museums as Containers of Sources Which Transmit Knowledge

Concerning the traditional view that museums contain primary sources which transmit historical knowledge, both teachers ( = 4.74; and museum educators ( position themselves with a mean score higher than 4.7.

More than seven out of ten teachers and museum educators state that they are totally in agreement with the academic perspective of museums. 75.85% of the teachers surveyed are totally in agreement and 23.3% are in agreement. Three out of ten educators are in agreement while seven out of ten claims to be totally in agreement.

3.2.2. Museums as Transmitters of Symbolic and Identity Values

The mean values awarded by educational agents to museums with a symbolic-identity perspective drops substantially in relation to the view of traditional museums. Teachers award a mean score of 4.49 (). On the other hand, educators give a mean score of 4.65 () to the view that museums should be considered as places which transmit symbolic and identity values.

56% of the teachers claim to be totally in agreement with the idea that museums transmit symbolic and identity values, 38.3% are in agreement, while 5% neither agree nor disagree. 70.6% of educators state that they are totally in agreement with the modern view of museums, while 23.5% are in agreement and 6% neither agree nor disagree.

3.2.3. Museums as Resources for the Socialisation and Transmission of Social and Civic Values

As far as the postmodern view of museums is concerned, the results do not differ too much from the previous view.

Teachers award a mean score of 4.52 to the statement that museums are resources for the development of a critical and responsible citizenship ( = 4.52; . Six out of ten teachers are totally in agreement, three out of ten are in agreement and the rest neither agree nor disagree (7.6%). Only two teachers are totally in disagreement with this statement.

As can be observed in Table 6, Q2 indicates that more than 50% award a score higher than four (totally in agreement), while only 25% give a score of less than four.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics of the analysis indicators for objective two of the research.

The mean score of the educators does not vary in relation to the previous conception ( = 4.65; . More than seven out of ten educators state that they are in total agreement with the function of museums as transmitters of social and civic values, almost three out of ten are in agreement and 6% neither agree nor disagree.

The Mann-Whitney U test determines that there are no statistically significant differences between the conception held by teachers regarding museums and that presented by museum educators. Therefore, the null hypothesis is accepted (H0: There are no statistically significant differences between the conception of teachers regarding museums and that of museum educators) and it is concluded that there are no statistically significant differences among the average ranges (p > 0.05).

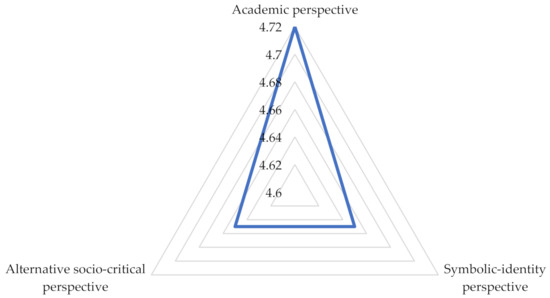

3.3. Purpose of School Visits to Museums

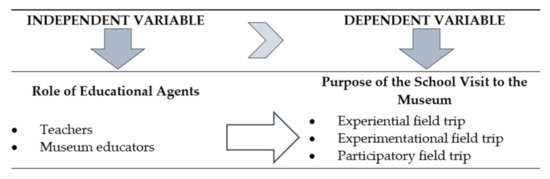

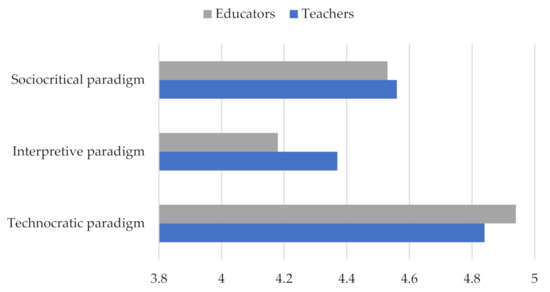

With the aim of evaluating the usefulness or purpose attributed by educational agents to school visits to museums (objective three) and based on the established design of the research, the independent variable is presented as the role of the educational agent in two levels (teacher and museum educator) and the dependent variable as the type of purpose of the school visit to the museum. The latter is divided into three analysis indicators (Figure 7). These, in turn, are related with the typologies of field trips established by [61,62,63], in accordance with the timing of the visit and the objective of the learning project:

Figure 7.

Variables which intervene in the achievement of objective three of the research. Source: Authors’ own work.

- To increase knowledge and cultural experiences

- To develop the skills of the scientific method

- To foster social participation, projecting it onto the environment

3.3.1. Field Trips to Museums as an Object of Study

The results show (Table 7) that the mean value awarded regarding teachers’ conceptions of the purpose of visits to museums for increasing knowledge and cultural experiences is 4.84 (). The estimated mean according to the view of the educators is greater with a difference of 0.10 points ( = 4.94; .

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics of the analysis indicators for objective three of the research.

According to the value of the third quartile, more than 75% of the teachers and museum educators award a score of 5. Specifically, on the one hand, 85.5% of teachers are totally in agreement and 13.4% are in agreement. Only 1.2% neither agree nor disagree. On the other hand, 94.4% are totally in agreement and the rest in agreement with the idea of school visits to museums being understood as an experiential field trip (typical of the technocratic paradigm).

3.3.2. Field Trips to Museums as Field Work

The teachers are in agreement with the fact that field trips to museums serve to develop the skills of the scientific method ( = 4.37; . Five out of ten teachers are totally in agreement with this statement, almost four out of ten claims to be in agreement, while one in ten neither agree nor disagree.

The museum educators evaluate field trips understood as fieldwork or experimentation with a mean score of 4.18 (. More than 50% award a score lower than 4, according to Q2. Only 35.30% are totally in agreement (awarding a score of five to this purpose), compared with 47.10% who are in agreement and 16.7% who neither agree nor disagree.

3.3.3. Field Trips to Museums as an Educational Context for Social Participation

The purpose of school trips to museums to foster social participation by projecting it onto the environment has a mean value higher than 4.50 for both educators ( = 4.53; and teachers ( = 4.56; ). According to the third quartile, this means that at least 50% of the educational agents awarded a score of five to the socio-critical paradigm and only 25% gave a score lower than 4 (Q1).

Six out of ten educational agents are totally in agreement with a type of participatory field trip, more than three out of ten are in agreement and around one in ten are indifferent.

The Mann-Whitney U statistical test shows that the differences between the museum educators and teachers regarding the purpose of school trips to museums are not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

4.1. Role of the Educational Agents: Degree of Responsibility

Far from determining whether this collaborative work takes place or not and who the agents involved are, the first aim was to determine the degree of responsibility that teachers and museum educators should have during school visits to museums. In this respect, Huerta and Ribera (2008) stated that:

- The educational exploitation of the visit should be the responsibility of the teachers, as it is, they who decide to visit the museum with their school groups and are aware of the reality and context of their class and the needs and expectations of their students.

- The museum and its educational staff should, for their part, be responsible for getting to know the school groups thanks to the information provided by the teacher and should adapt their educational programme accordingly.

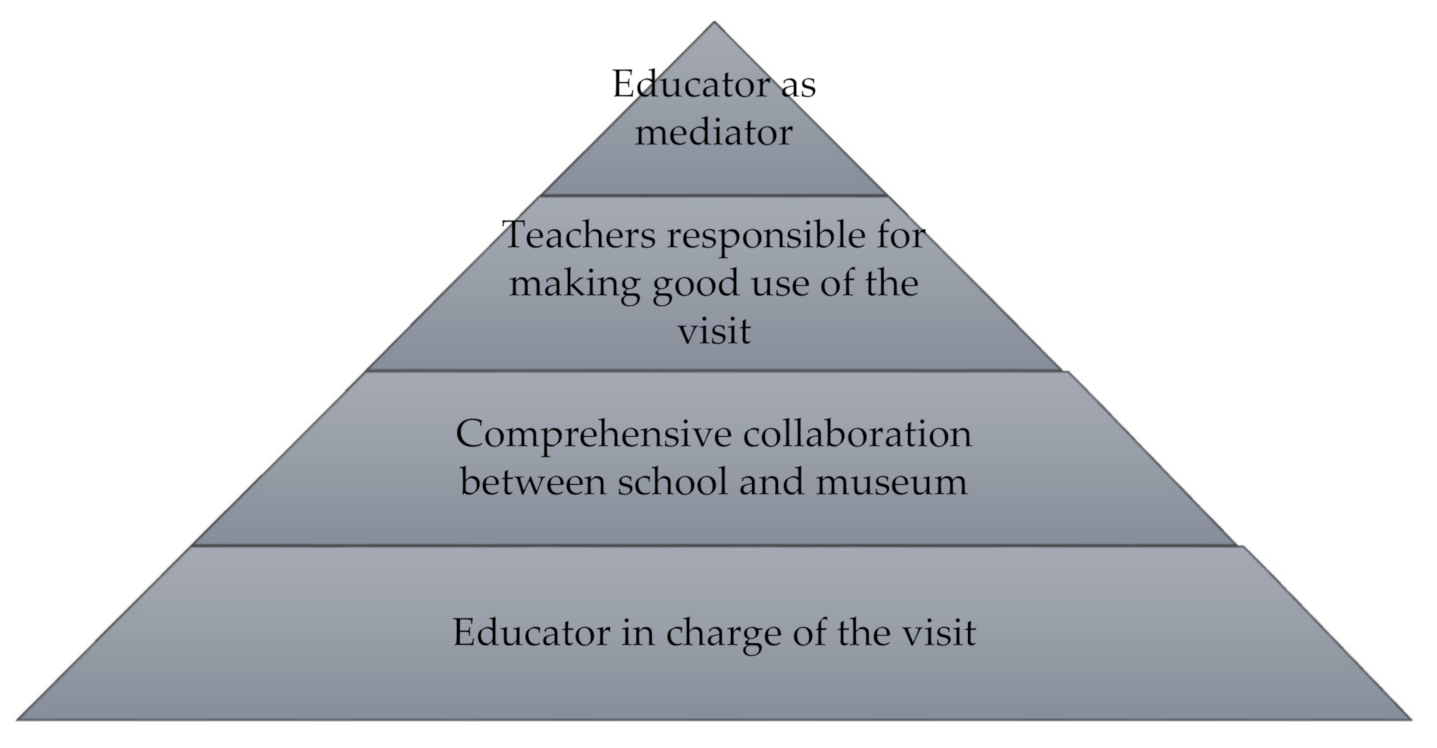

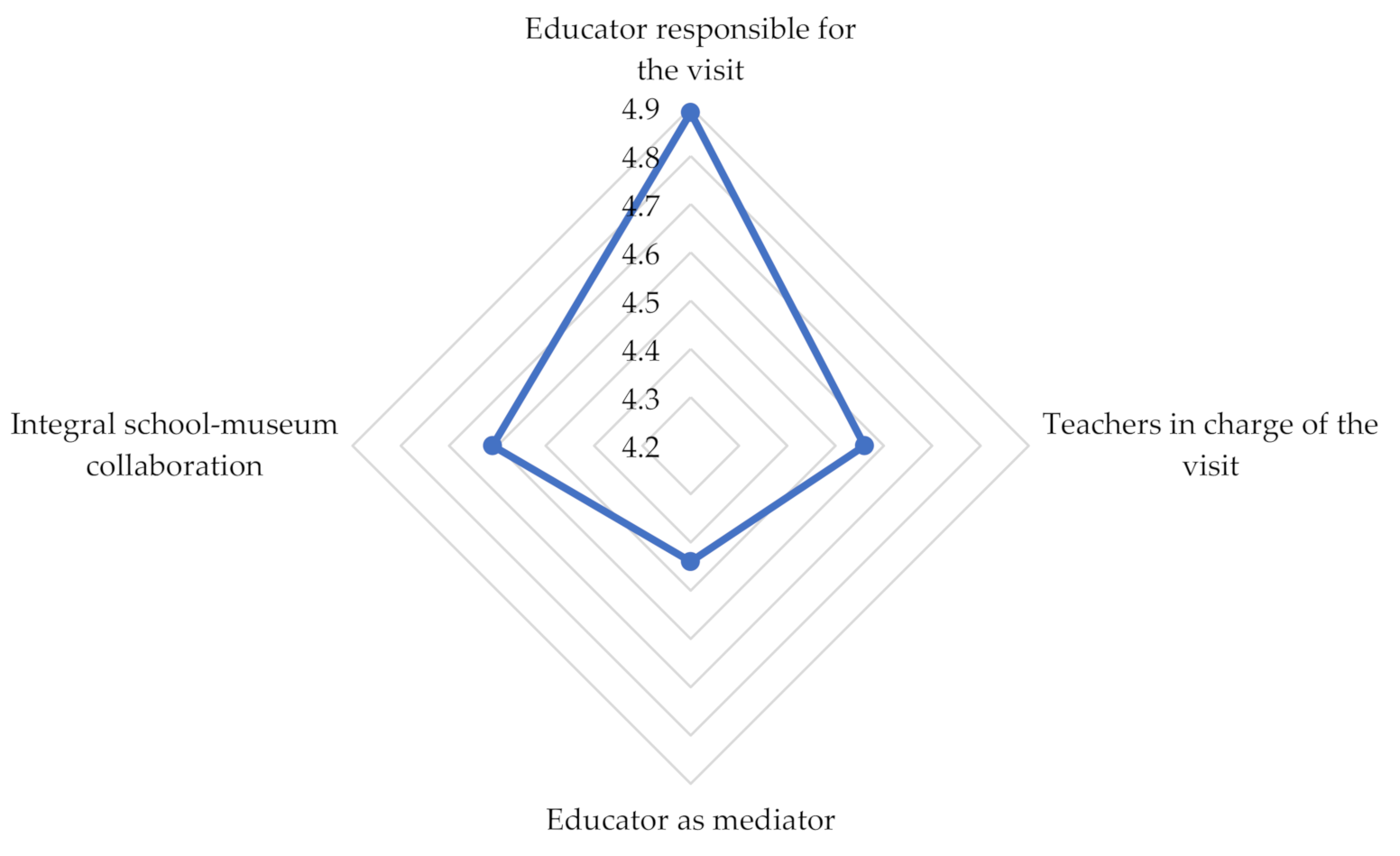

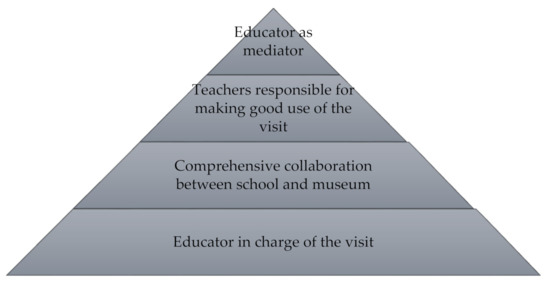

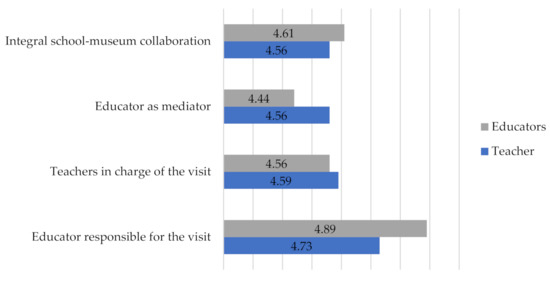

As reflected in the pyramid of responsibility (Figure 8) and summarised in Figure 9, according to both teachers and educators, the maximum degree of responsibility falls upon museum educators. Both teachers and museum educators (the latter are, on the whole, in total agreement) consider that museum educators are most responsible for school visits to museums, since the connection between the visit and the interests of the group derives from this person ( = 4.81). Thus, the educational agents attribute greater responsibility to full collaboration between schools and museums ( = 4.58). Next is the responsibility of the teachers, as those in charge of the educational exploitation of the output ( = 4.57). The agents give less importance to the educator as a mediator, i.e., as a link between the museum and the school ( = 4.5).

Figure 8.

Pyramid showing the results of the degree of responsibility of the educational agents. Source: Authors’ own work.

Figure 9.

Mean scores of the degree of responsibility of educational agents and teachers, according to museum educators and teachers. Source: Authors’ own work.

These findings can be compared with those of the qualitative study by Hannon & Randolph (1999) [30], who consider that “educators at all five of the museum sites felt their role was to serve as a bridge between schools and museum” (p. 26). In contrast, our research indicates that while educational agents (teachers and educators) see educators as important, they are not considered to be the most important.

The findings reported by [30] on the responsibilities that museum educators attribute to themselves are based on three main functions:

First, educators wish to connect the museum and the school population (…). Second, museum educators feel responsible for merging students’ understanding of physical objects with abstract concepts (…). Third, museum educators hope to connect real-word experiences, that their museums provide, with information that students study in school.(p. 26)

The results proposed in this qualitative research coincide with those of the educators in this study: Museum educators feel fully responsible for this connection to the interests of the group, although they agree to a lesser extent that they serve as a link between the museum and the school (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Radial with the mean results of the responsibility that the museum educator attributes to educational agents in a school visit to a museum. Source: Authors’ own work.

According to [30], educators also consider that teachers are responsible for the willingness to collaborate during the museum experience. This is in line with what is proposed in the present study. However, by presenting the authors’ research with a qualitative design based on information gathered from an interview, the interview has been able to infer some of the responsibilities that educators attribute to teachers, which are related to the communication of curricular objectives, the planning of pre-visit activities, and the evaluation of learning. These are summarised as follows:

- The teacher’s responsibility to communicate his/her applicable curriculum objectives with the museum educators so that those at the museum can best serve the students’ needs.

- Teachers should prepare their students for a museum visit by doing pre-visit activities in the classroom.

- The teacher is also responsible for following up on the students’ learning that took place at the museum (p. 27).

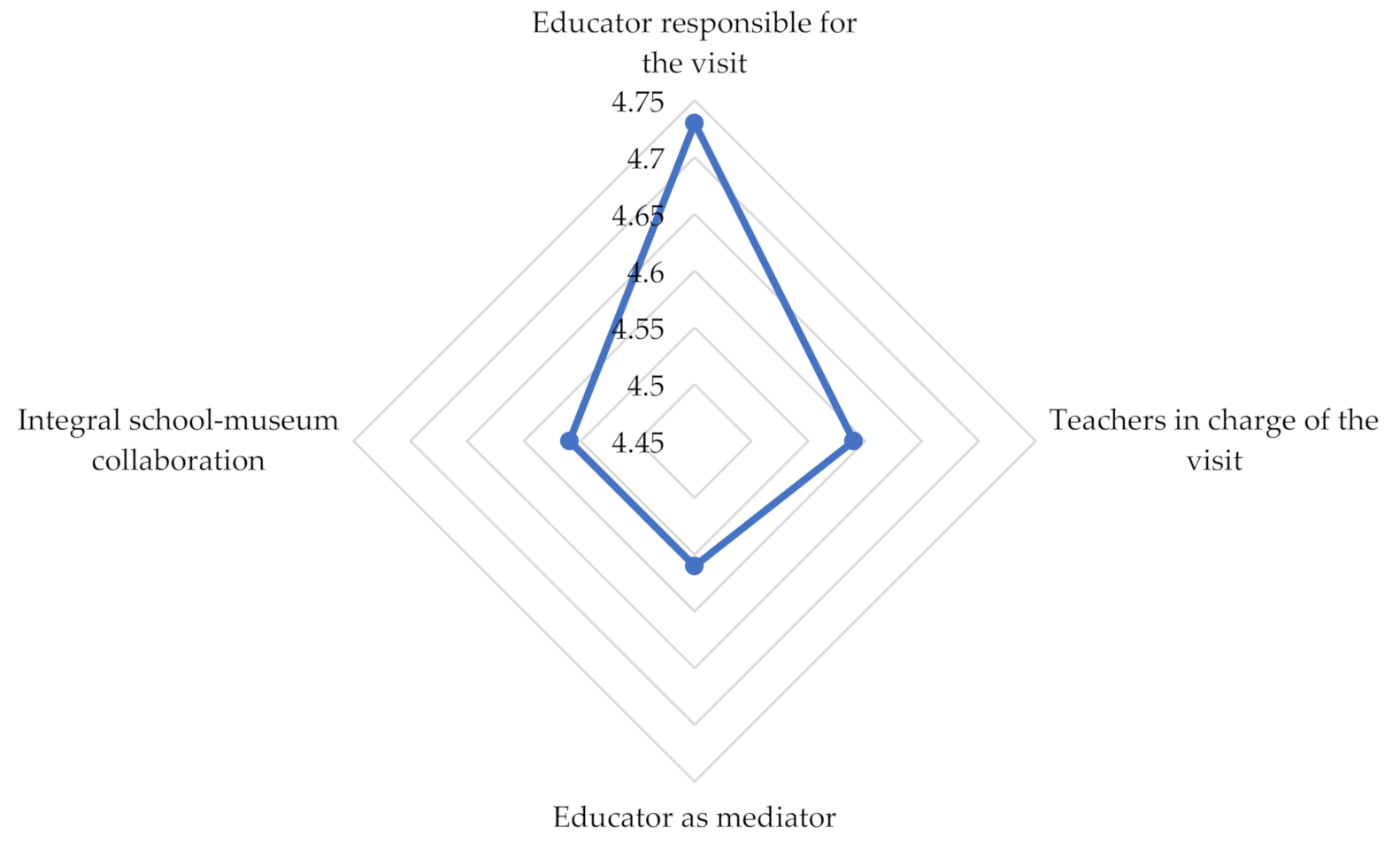

The qualitative study carried out, via interviews with educators from five museums, did not take into account in its results the views of the other partners in the collaboration: the teachers. In our research, the views of the teachers attribute greater responsibility to the educators as connectors of the visit with the interests of the group, followed by the joint collaboration of the museum’s educational managers. With a mean score of 4.56 they agree that they should be responsible for the educational exploitation of the visit (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Radial with the mean results regarding the responsibility attributed by teachers to the educational agents in school visits to museums. Source: Authors’ own work.

Teachers and educators agree on the importance and responsibility they hold for connecting the visit with the interests of the group, with curricular and/or teaching requirements. These results coincide with the theoretical postulations that authors such as [14,31,32] among many others, have given to educational agents who intervene in school visits to a heritage museum environment.

4.2. Concept of Museum

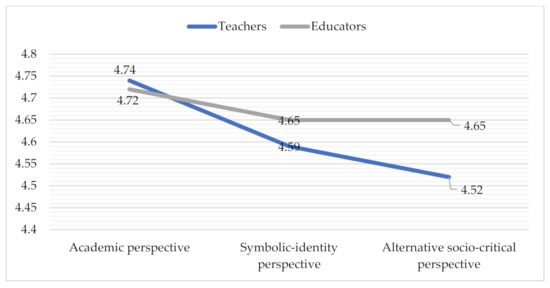

The study also aimed to find out what views the participating educators and teachers have of museums. The research carried out since the end of the last century by the research group of the University of Huelva (DESYM) directed by Professor Jesús Estepa has, over the years, formed a series of categories (in levels of progression) on the conception of heritage. These conceptions were taken into account in order to establish a classification of the concept of museum that would, in some way, comprehend these conceptions.

Based on this premise, the results presented on the view of heritage according to [40] show that heritage managers (including museum educators) have a more complex view of heritage than teachers. Thus, teachers focus on heritage using a more aesthetic or historical criterion (traditional perspective) or symbolic identity.

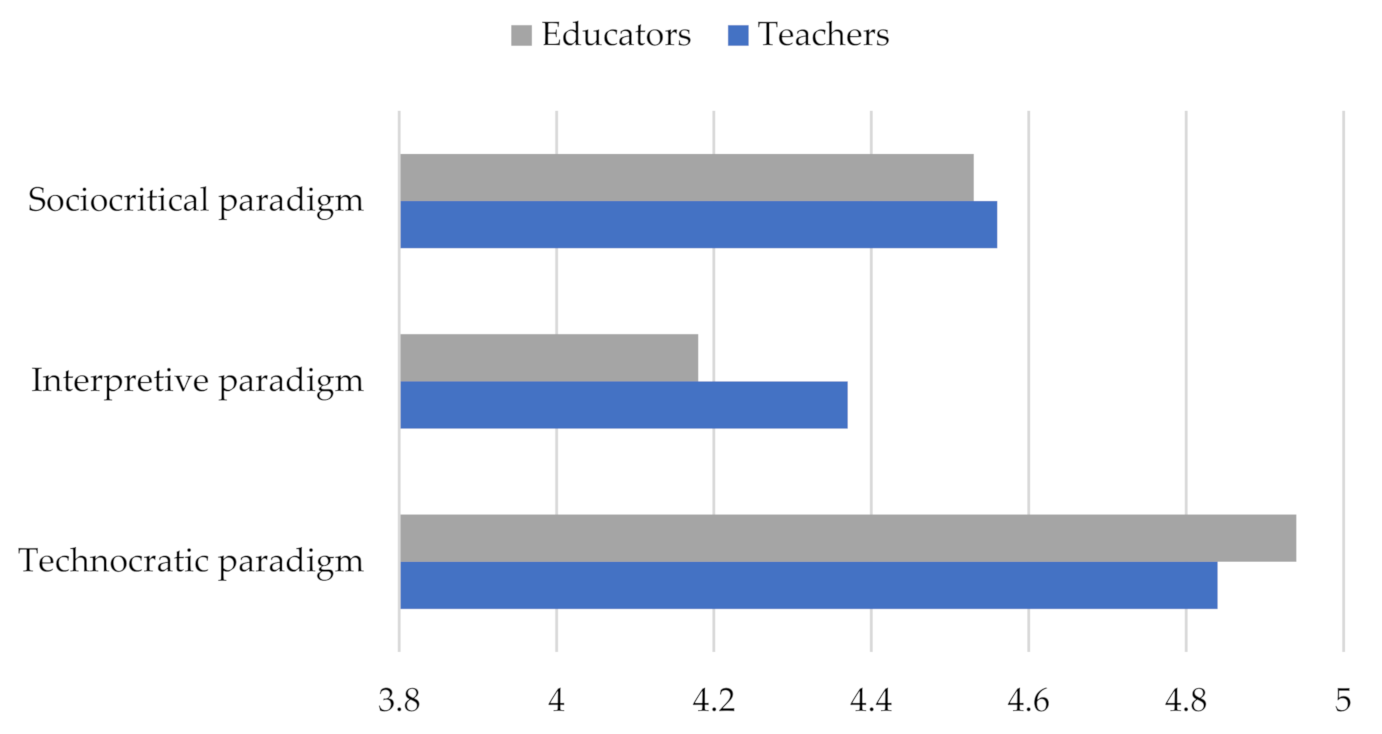

This view may well resemble the results of this study. Educational agents are, on the whole, in total agreement with the traditional view of the museum that confers an academic perspective upon heritage, focusing on museums as containers of heritage understood as primary sources that transmit historical knowledge ( = 4.73). As can be seen in Figure 12, the symbolic-identity perspective (i.e., the understanding of the museum as a space in which symbolic and identity values are transmitted) is the concept of a modern museum that, according to the educational agents, is presented with an average agreement of 4.62. These results agree with those proposed by the authors concerning the view of heritage with a symbolic-identity perspective. Finally, the alternative socio-critical perspective (postmodern concept) that considers museums to be spaces for the development of a critical responsible citizenship is, despite its high score ( = 4.58), the aspect upon which educational agents least agree.

Figure 12.

Mean scores on the concept of museum from the perspective of the educational agents. Source: Authors’ own work.

On the other hand, the results presented by [40] consider that 75.8% of the heritage managers participating in their research view heritage as having a historical perspective, followed by those who have a symbolic-identity conception (9.1%). As can be seen in Figure 13, the museum educators who participated in this research show a very similar view.

Figure 13.

Radial with the mean results of the educators’ conception of museums. Source: Authors’ own work.

The teachers’ views do not differ from those of museum educators. As [71] indicate, the group of teachers highlights the predominance of a conception of heritage based on aesthetic and historical criteria.

These results, with the predominance of a traditional view of museums, may mainly be due to the fact that the model of heritage dissemination still presents an academic perspective. According to this view, traditional resources are used for the dissemination of heritage and teaching based on transmitting knowledge of facts and information of a purely cultural, erudite and sometimes anecdotal nature [72]. These results will be contrasted in the following section with the view educational agents have of the purpose of school visits to archaeological museums.

Another reason for the predominance of a traditional view of museums among teachers and museum educators may be due to the type of museum and the museum context. Historical or archaeological museums, in contrast to science museums or modern art museums, for example, tend to have a more academic discourse. In addition, as [73] state, in the case of historical-artistic museums, in which the object of the exhibition is the heritage item or the work of art, it is extremely rare to find exhibitions which are designed bearing in mind the types of public which could be the objective of their proposal.

Furthermore, in Spanish museums the predominant discourse continues to be that of the modern rather than the postmodern museum. An action-research project by [74] based on the concept of post-museum at the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois (USA), determined that, instead of transmitting values and knowledge, post-museum communication emphasises the construction of meaning by active individual agents and celebrates the diversity of viewpoints. It is a postmodern conception based on the critical and social function of teaching with heritage.

4.3. The Purpose of Field Trips

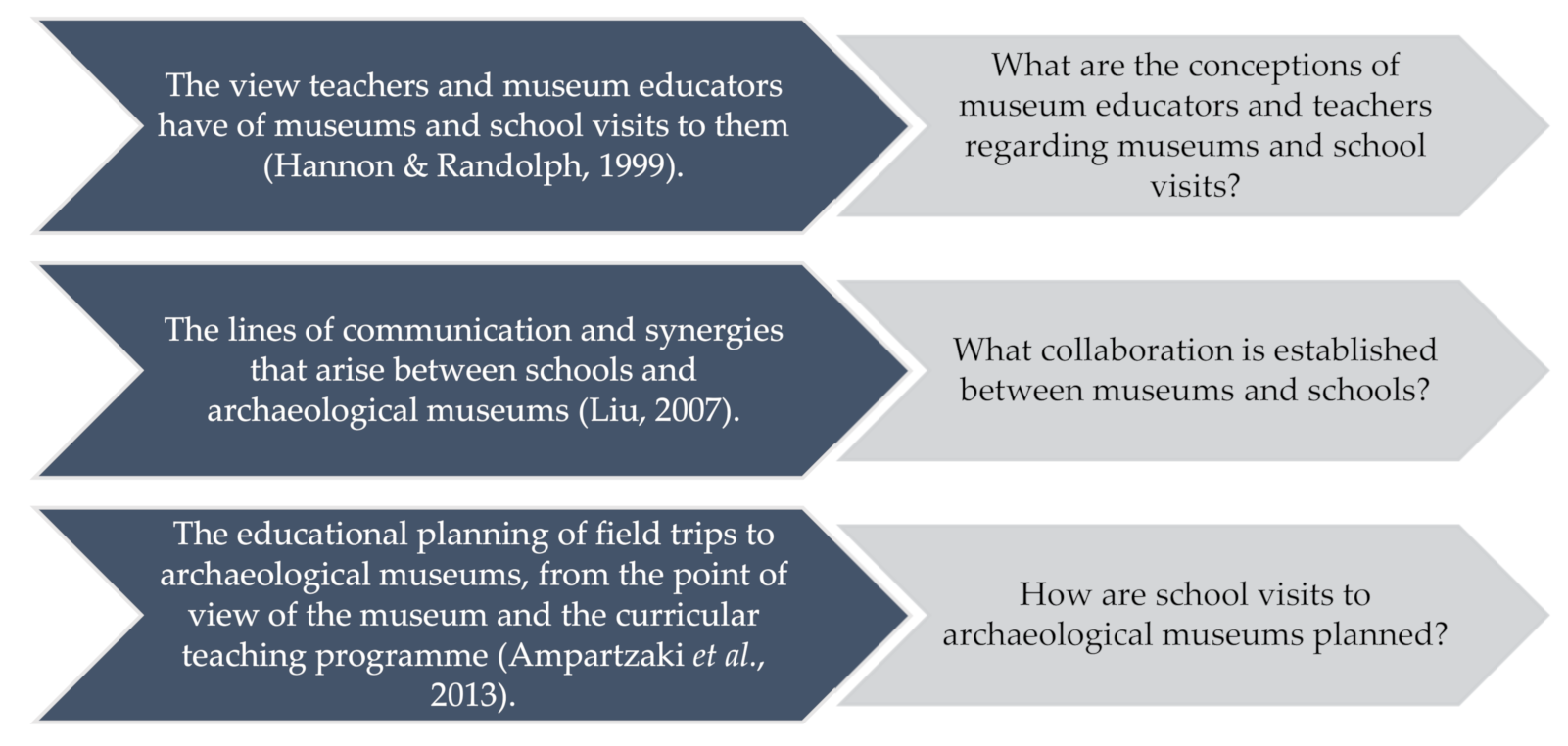

If the view of museums that most educational agents agree on (the traditional view with an academic perspective) is taken into account, then it must be verified whether this view is related to the purpose that the educational agents consider that school visits to museums should have.

As seen in Figure 14, both educators and museums agree that school visits to museums serve to increase students’ knowledge and cultural experiences (= 4.89). Following the purpose in which social participation in the environment is estimated (= 4.54), with a mean score of 4.27 is the purpose that places the school group in the development of activities of the scientific method. There is a clear difference in the paradigms of the museums and the teachers, with teachers agreeing (4.37) on the purpose of the group’s learning by inquiry, while educators agree less on this purpose (4.18).

Figure 14.

Mean results of the score on the purpose of school visits to museums according to the educational agents. Source: Authors’ own work.

The most widely-accepted purpose of museum visits is to broaden students’ information and knowledge and to enrich them culturally. No studies were found that determine what conception educational agents have of the purpose of school visits. Formal school trips to museums generally seek to enhance students’ historical knowledge or to enrich them culturally without there being any direct impact on the teaching and learning process of history. Rather, the visit is seen as anecdotal and as a one-off occasion [33,40].

5. Conclusions

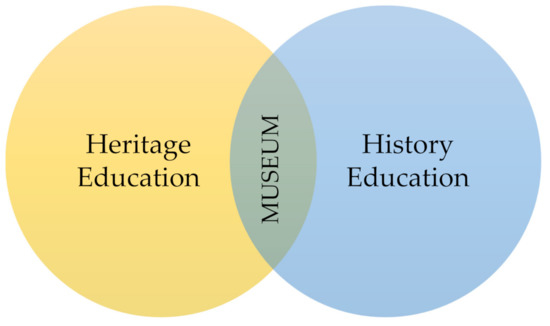

The main conclusions in response to the research questions are detailed below (Figure 15):

Figure 15.

Relation between the theoretical model of MUSELA DO © and MUSELA EDU © and the general research questions. Source: Authors’ own work.

In response to the question What conceptions do museum educators and teachers have of museums and school visits? the most significant conclusions to be drawn are directly related with:

- Determining the degree of responsibility educational agents should assign themselves in the visits.

- Identifying the educational agents’ level of conception of the museum.

- Rating how useful educational agents feel school visits are.

This is intended, first of all, to answer the question: What degree of responsibility is attributed to educational agents by museum educators and teachers.

- The teacher attributes greater responsibility to museum educators as connectors of the school visit with the interests of the school group.