The Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage from the Perspective of Civic Participation: The Informal Education of Chinese Embroidery Handicrafts

Abstract

1. Introduction

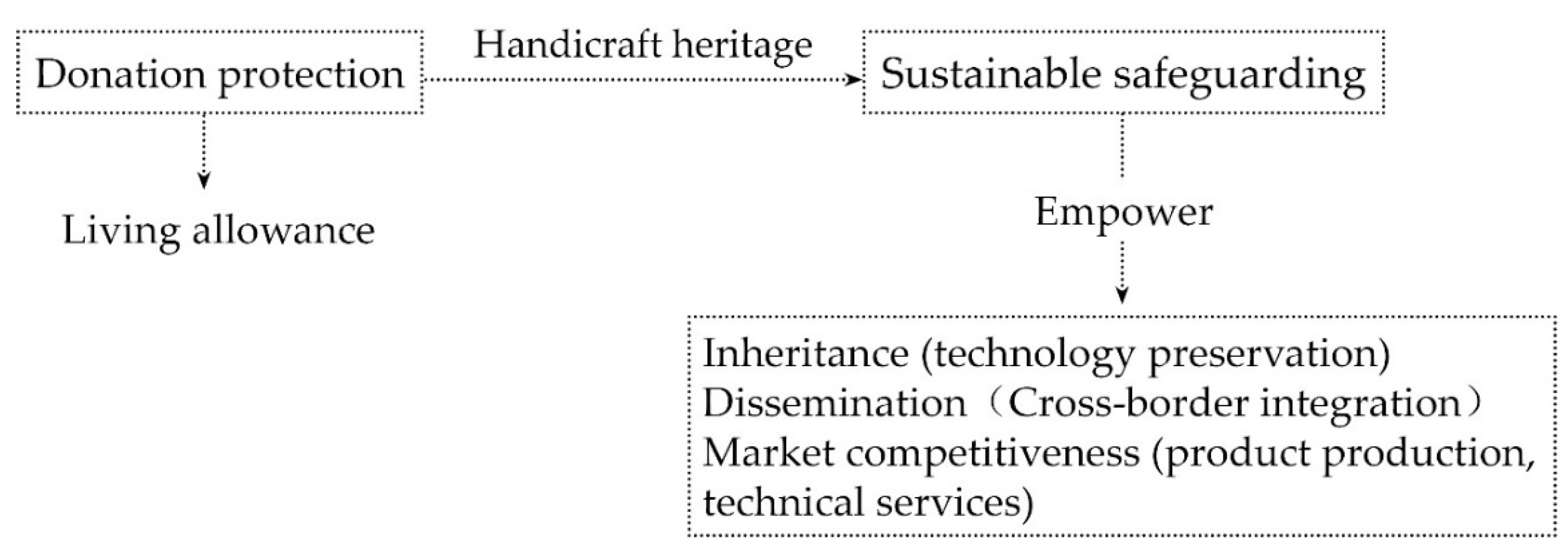

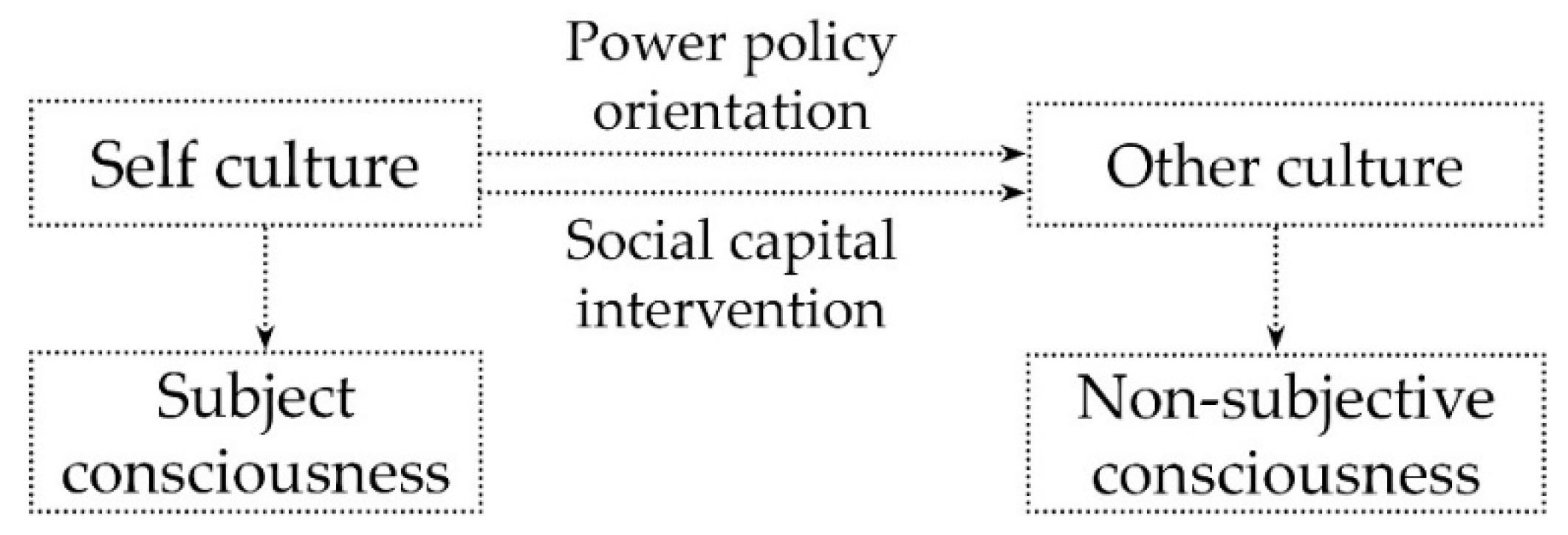

1.1. Intangible Cultural Heritage and Civic Cultural Participation

1.2. Research Object and Purpose

2. Literature Review

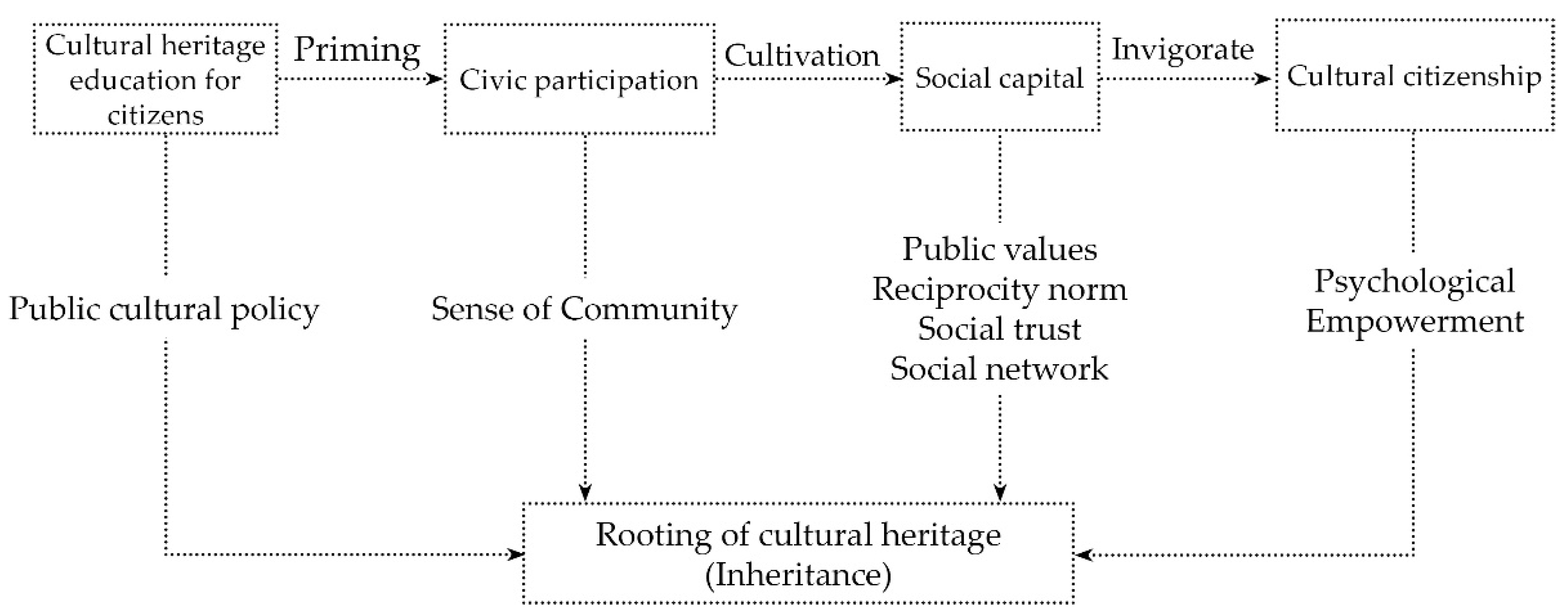

2.1. Citizen Cultural Heritage Education and Cultural Citizenship

2.2. Social Capital and Citizen Participation

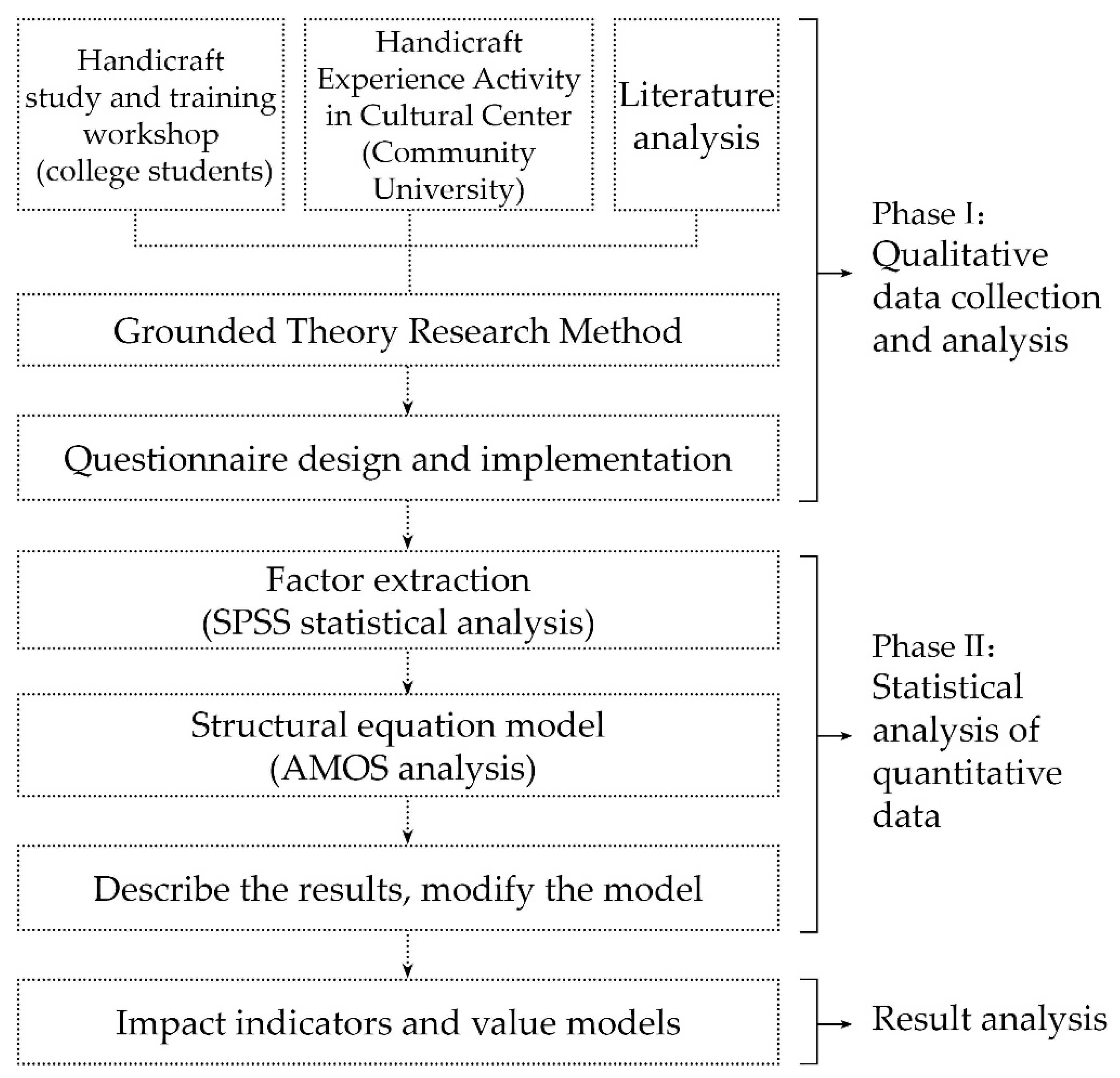

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Process

3.2. Phase I: In-Depth Interview Method and Interview Design

3.3. Phase II: Questionnaire Survey Method and Design

| Variable | Indicator | Number of Items | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Identity | Cognition | 6 | [25] (Zhu,2018) |

| Familiarity | 6 | [35] (Xiao&Guo,2018) | |

| Dissemination | 6 | [2] (Liu,2006) | |

| Participation | 6 | [4] (Dahlgren &Alvares,2013) | |

| Perceived Value | Cultural continuity | 4 | [25] (Zhu,2018) |

| Educational value | 4 | [24] (Heater,2004) | |

| Aesthetic value | 4 | [33] (Throsby,2001) | |

| Public value | 3 | [26] (Houkamau,2010) | |

| ICH’s Authenticity | Authenticity | 3 | [34] (Yan& Chiou,2020) |

| Historic | 3 | [5] (Benmayor,2002) | |

| Cultural Identity | Identity | 5 | [7] (Flores,1997) |

| Sense of accomplishment | 5 | [3] (Putnam,2015) | |

| Sense of honor | 5 | [12] (Yang,2016) | |

| Social responsibility | 5 | [36] (Coleman,1998) | |

| Community connection | 5 | [37] (Dalton,2007) |

3.4. Results and Analysis

3.4.1. Sample Characteristics

3.4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.4.3. Reliability and Validity Test

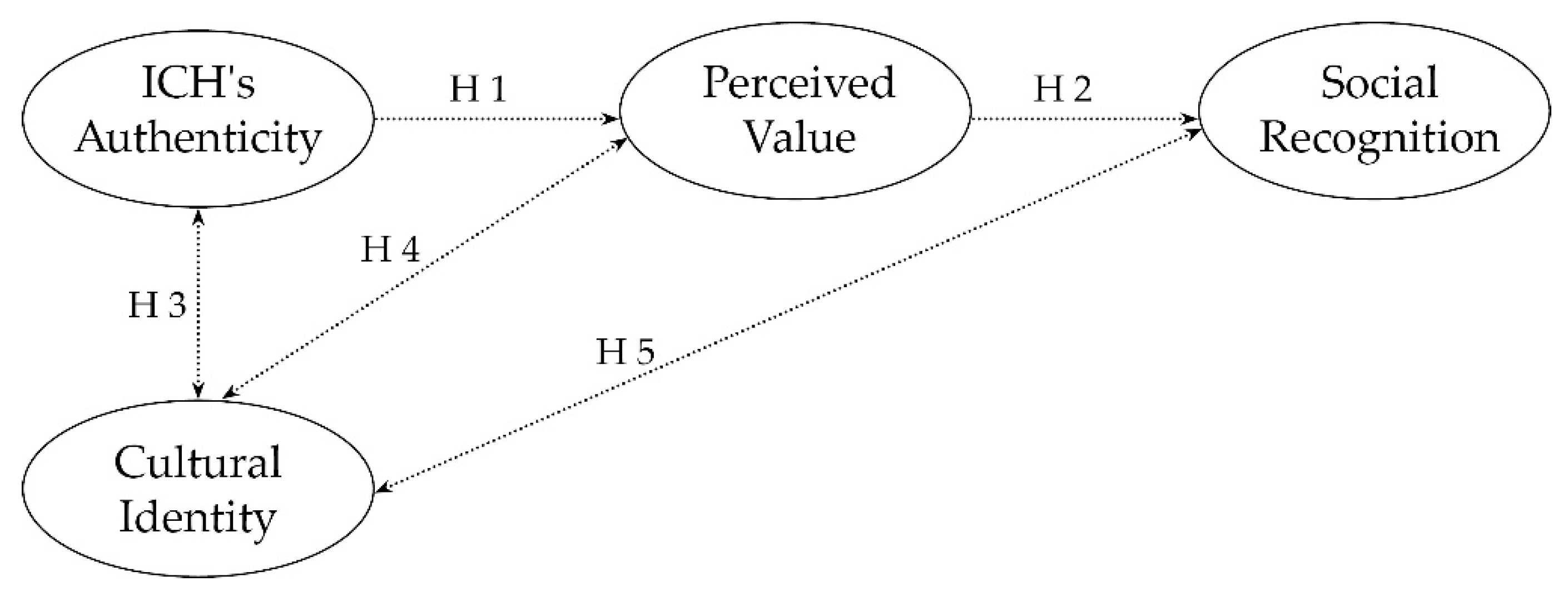

3.5. Overall Model Structure Analysis

- The value of the indirect effect is 0.284. The 95% confidence interval of bias-corrected and percentile does not contain 0. The p value is less than 0.05, indicating that the perceived value does play a significant intermediary role in the relationship between ICH’S authenticity and social recognition.

- The direct effect value of “ICH’S authenticity → Perceived value” is 0.393. The 95% confidence interval of bias-corrected and percentile does not contain 0, and the p value is less than 0.05, so the direct effect is significant.

- The direct effect value of “Perceived value → Social recognition” is 0.723. The 95% confidence interval of bias-corrected and percentile does not contain 0, and the p value is less than 0.05, so the direct effect is significant.

- The total effect value of “ICH’S authenticity → Perceived value” is 0.393. The 95% confidence interval of bias-corrected and percentile does not contain 0, and the p value is less than 0.05, so the direct effect is significant.

- The total effect value of “ICH’S authenticity → Social recognition” is 0.284. The 95% confidence interval of bias-corrected and percentile does not contain 0, and the p value is less than 0.05, so the direct effect is significant.

- The total effect value of “Perceived value → Social recognition” is 0.723. The 95% confidence interval of bias-corrected and percentile does not contain 0, and the p value is less than 0.05, so the direct effect is significant.

4. Research Result and Discussion

4.1. The Rationality of the Theoretical Model Is Supported

4.2. Reflections on the Sustainable Development of Intangible Cultural Heritage

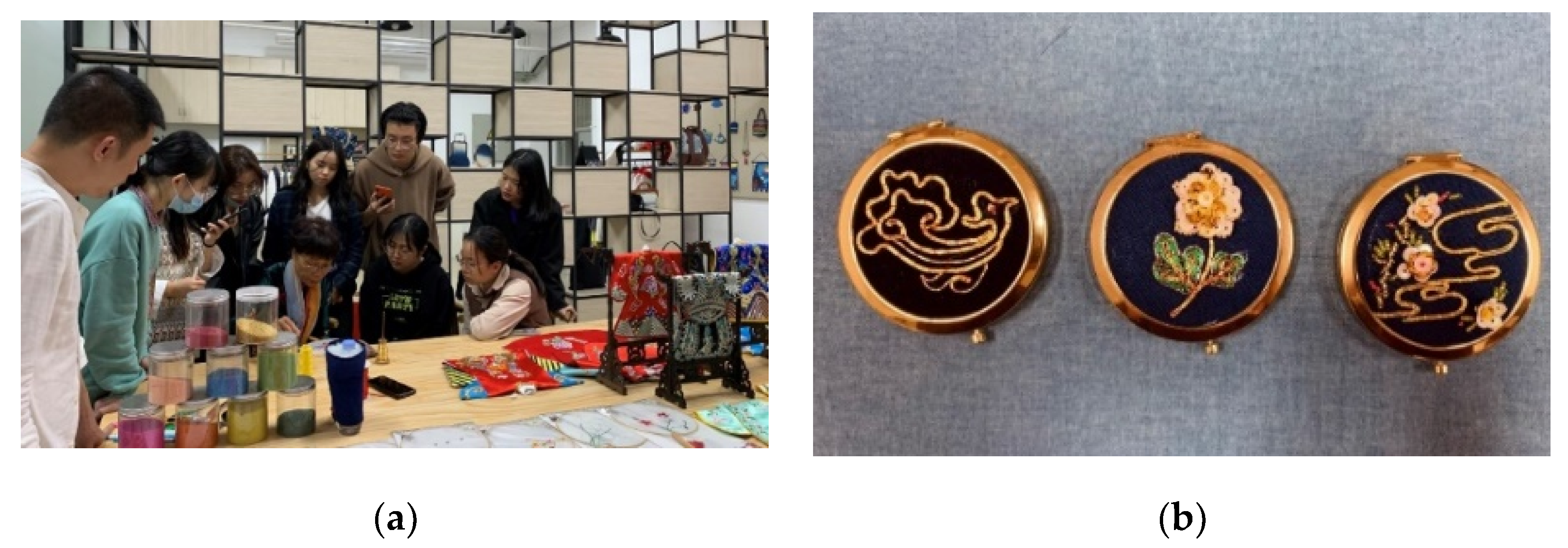

- Embroidery with strong authenticity (Item 9) has the weakest score of 0.499 on the “authenticity of embroidery technique” and the strongest score of 0.657 on the “decorative art of embroidery.” It is assumed that the embroidery with strong authenticity of ICH has weak authenticity (authenticity) and strong decoration (social recognition), which supports Hypothesis H1.

- Embroidery with medium authenticity (Item 10) has the weakest score (0.431) on the “historically of embroidery culture” scale and the strongest score (0.631) on the “seriousness of decorative patterns” scale. The embroidery with medium authenticity of ICH is assumed to score low on cultural history (perceived value) and score high on pattern seriousness (social recognition), supporting Hypothesis H2.

- Embroidery with weak authenticity (Item Q11) has the weakest score of 0.496 on the “authenticity of embroidery skills” and the strongest score of 0.731 on the “seriousness of decorative patterns.” It is assumed that the embroidery with the weakest authenticity of ICH has weak authenticity (authenticity) and strong pattern seriousness (social recognition), which supports Hypothesis H1.

4.3. Research Conclusion

4.4. Discussion

- The research field and sample size can be expanded to better reduce the research errors caused by regional differences and sample size so that the research conclusions have broader applicability.

- In the future, we can expand the scope of research, study the role of intangible cultural heritage in algorithmic content distribution and social communication, find the weight indicators in the algorithm model, and make data the standard for intangible cultural heritage protection and communication.

- Due to the limitation of the model, it was not possible to conduct a correlation study on the influence of demographic variables and citizen identification. Future research can study the effects of demographic variables, such as gender, occupation, age, educational background, and cultural citizenship identity, to better understand the role of the public in cultural citizenship identity recognition.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Code Number | Gender | Occupation | Interview Time | Interview Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Female | Teacher | 2020.11.23 | University campus |

| F2 | Female | Teacher | 2020.11.23 | University campus |

| F3 | Female | Student | 2020.11.23 | University campus |

| F4 | Female | Student | 2020.11.23 | University campus |

| F5 | Female | Student | 2020.11.24 | Public cultural hall |

| F6 | Male | Student | 2020.11.24 | Public cultural hall |

| M1 | Female | Citizen | 2020.3.6 | Public cultural hall |

| M2 | Male | Citizen | 2020.3.6 | Public cultural hall |

| M3 | Male | Citizen | 2020.3.6 | Public cultural hall |

| M4 | Male | Citizen | 2020.3.6 | Public cultural hall |

References

- Song, J.H. (Ed.) Annual Development Report on Chinese Intangible Cultural Heritage Safeguarding (2019), 1st ed.; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2020; p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.M. Right, and Development: The Principle of Non-material Culture Heritage Protection. J. Southwest Minzu Univ. 2006, 173, 191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, D.R. Marking Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; W, L.; Lai, H.R., Translators; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2015; pp. 216–226. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren, P.; Alvares, C. Political Participation in an age of Mediatisation. Javnost Public 2013, 20, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmayor, R. Narrating cultural citizenship: Oral Histories of first-generation college students of Mexican origin. Soc. Justice 2002, 29, 96–121. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, C.; Gattinger, M.; Jeannotte, M.S.; Straw, W. (Eds.) Accounting for Culture: Thinking through Cultural Citizenship; University of Ottawa Press: Ottawa, Canada, 2005; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, W.V.; Benmayor, R. (Eds.) Latino Cultural Citizenship: Claiming Identity, Space, and Rights; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1997; p. 322. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, A. Cultural citizenship as subject-making: Immigrants negotiate racial and cultural boundaries in the United States. Curr. Anthropol. 1996, 37, 737–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D.C. Heritage pasts and heritage presents: Temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2001, 7, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A. Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, B.S. Outline of a General Theory of Cultural Citizenship in Culture and Citizenship; Stevenson, N., Ed.; Sage: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India, 2001; pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. Cultural Citizenship: A New Trend of Citizenship Research. J. Fujian Inst. Educ. 2016, 5, 128. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. Study on Public Participation in the Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage—A Case Study on Protection of Yunnan Midu Huadeng Opera. J. Dali Univ. 2018, 11, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. “Continuity” in the protection of contemporary cultural heritage. China Cult. Herit. 2019, 5, 52–58, CNKI: SUN: CCRN.0.2019-05-009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.Y.; Ma, Z.Y. Research on the Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage from the Perspective of Cross-cultural Education. J. Hebei Univ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.R. Social Mobilization, Ethnographic Methodology, and Reconstruction of the Global Society: Experience and Inspiration of the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Mexico. Stud. Ethn. Lit. 2018, 3, 29–38, CNKI: SUN: MZWX.0.2018-03-004. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, C. Towards Cultural Citizenship: Tools for Cultural Policy and Development; Bank of Sweden Tercentenary Foundation: Stockholm, Sweden, 2002; pp. 13–60. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2153304 (accessed on 27 April 2021). [CrossRef]

- Francis, F.; Marwah, S. Comparing East Asia and Latin America: Dimensions of Development. J. Democr. 2000, 11, 80–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lochner, K.A.; Kawachi, B.; Kennedy, P. Social capital: A guide to Its measurement. Health Place 1999, 5, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyx, J.; Bullen, P. Measuring social capital in five community. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2000, 36, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, J. Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: Toward a theory for community psychology. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 1987, 15, 121–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkin, D.D.; Zimmerman, M. Empowerment theory, research, and application. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 1995, 23, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, J.H.; Schumacher, S. Research in Education: Evidence-Based Inquiry, 7th ed.; Zeng, T.S., Translator; Educational Science Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2013; p. 355. [Google Scholar]

- Heater, D. Citizenship: The Civic Ideal in World History, Politics, and Education, 3rd ed.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2004; pp. 141–163. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. A study on the Communication’s Cognition of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in the New Media Form—A Case Study of Domestic and Foreign Handmade Paper. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Science and Technology of China, Anhui, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Houkamau, C. Identity construction, and reconstruction: The role of socio-historical contexts in shaping Māori women’s identity. Soc. Identities 2010, 16, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibley, C.G.; Houkamau, C.A. The multi-dimensional model of Māori identity and cultural engagement: Item Response Theory Analysis of Scale Properties. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minority Psychol. 2013, 19, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.X. The Structure of Consumers’ Affects in the Context of the Chinese Culture and their Effects on the Equity of China’s and Foreign Brands. Manag. World 2008, 6, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, F.R. Culture & Social Anthropology: An Overture; Wang, Z.J., Translator; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2009; pp. 30–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H. Introduction to Cultural Heritage (Part 1)—Typologies and Values of Cultural Heritage. Study Nat. Cult. Herit. 2020, 1, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Economics and Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.J.; Chiou, S.C. Dimensions of Customer Value for the Development of Digital Customization in the Clothing Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Guo, Z.H. (Eds.) Citizenship and Civil Society Studies; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2018; Volume 3, pp. 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, J.H.; Maurice, J.E.; Abraham, W. Community Psychology: Linking Individuals and Communities; Wadsworth Pub Co: Belmont, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 312–393. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.L. Questionnaire Statistical Analysis Practice—SPSS Operation and Application; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2010; p. 192. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, F.D. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Market. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Quick Guide to Education Indicators for SDG 4. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000265396?posInSet=13&queryId=f3fc0ba6-1594-428e-adc9-4a051828b727 (accessed on 5 April 2021).

| Percentage | Percentage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male-189 Female-157 | 54.62% 45.37% | Education level | Postgraduate and above College and undergraduate High school Junior high school Primary school Other | 10.40% 86.12% 1.44% 1.44% 0.57% |

| Age | Under 18 18–25 26~30 31~40 41~50 51~60 Above 60 | 0.57% 27.16% 43.93% 20.80% 4.33% 2.60% 0.57% | Occupation | Full-time student Production staff Marketing/Sales/Staff Designer Consultant/Consulting Teacher Other professionals | 16.47% 13.58% 27.74% 14.16% 4.62% 9.24% 14.16% |

| Component | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Q6_1 | Date of Cultural and Natural Heritage Day | 0.800 | 0.056 | 0.070 | 0.086 |

| Q6_4 | Intangible Cultural Heritage WeChat official account | 0.733 | 0.208 | 0.038 | 0.136 |

| Q6_2 | The location of the intangible cultural heritage museum in the city | 0.730 | 0.094 | 0.088 | 0.090 |

| Q6_3 | Cultural experience activities organized by the intangible cultural heritage museum | 0.729 | 0.036 | 0.143 | 0.154 |

| Q7_5 | Intangible cultural heritage + E-commerce | 0.710 | 0.217 | 0.178 | –0.148 |

| Q8_3 | Intangible cultural heritage training courses organized by communities and associations | 0.704 | 0.129 | –0.046 | 0.231 |

| Q6_5 | Chinese traditional culture/cultural heritage articles | 0.691 | 0.061 | 0.243 | 0.075 |

| Q8_2 | Intangible heritage experience course organized by the inheritor’s studio | 0.681 | –0.071 | 0.291 | 0.012 |

| Q7_1 | Intangible cultural heritage + lectures (online, offline) | 0.653 | 0.226 | –0.150 | 0.233 |

| Q8_4 | Handicraft experience courses of commercial training institutions | 0.645 | –0.092 | 0.401 | –0.076 |

| Q7_8 | Intangible cultural heritage + public publication | 0.629 | 0.022 | 0.009 | 0.151 |

| Q8_1 | Weekend intangible cultural heritage experience | 0.620 | 0.178 | 0.050 | 0.108 |

| Q7_7 | Intangible cultural heritage + live program | 0.567 | 0.273 | –0.015 | 0.150 |

| Q8_5 | Purchase intangible cultural heritage DIY experience package | 0.567 | 0.142 | 0.124 | –0.337 |

| Q14_3 | Traditional craftsmanship continues the historical continuity of local culture | 0.150 | 0.765 | 0.102 | 0.050 |

| Q17_3 | The value of historical witness | 0.047 | 0.738 | 0.050 | 0.112 |

| Q9_3 | The decorative art of embroidery | 0.103 | 0.677 | 0.015 | 0.260 |

| Q10_4 | Inheritance of embroidery craftsmanship | 0.125 | 0.627 | 0.330 | 0.090 |

| Q14_10 | Intangible cultural heritage is a cultural wealth shared by all people | 0.218 | 0.553 | 0.415 | –0.083 |

| Q10_6 | The seriousness of the decorative pattern | 0.231 | –0.003 | 0.733 | 0.140 |

| Q10_2 | The authenticity of embroidery skills | 0.037 | 0.206 | 0.722 | 0.085 |

| Q10_5 | The history of embroidery culture | 0.022 | 0.255 | 0.549 | 0.150 |

| Q14_7 | Close the interaction between myself, the community, and others | 0.179 | 0.194 | 0.190 | 0.696 |

| Q14_6 | Connects the relationship between my daily life and traditional culture | 0.193 | 0.126 | 0.396 | 0.637 |

| Q14_5 | Enlightened me to respect and think about the cultural life of myself and others | 0.257 | 0.437 | 0.021 | 0.561 |

| Factors | Item | CITC | Cronbach’s α Value When the Item was Deleted | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Recognition α = 0.917 | Q6_1 Q6_4 Q6_2 Q6_3 Q8_3 Q7_8 | 0.755 0.716 0.691 0.700 0.666 0.564 | 0.906 0.908 0.909 0.908 0.910 0.914 | 0.800 0.733 0.730 0.729 0.704 0.629 |

| Perceived Value α = 0.774 | Q14_3 Q17_3 Q9_3 Q10_4 Q14_10 | 0.620 0.541 0.527 0.547 0.506 | 0.708 0.735 0.741 0.733 0.746 | 0.765 0.738 0.677 0.627 0.553 |

| ICH’s Authenticity α = 0.632 | Q10_6 Q10_2 Q10_5 | 0.473 0.461 0.407 | 0.495 0.518 0.580 | 0.733 0.722 0.549 |

| Cultural Identity α = 0.676 | Q14_7 Q14_6 Q14_5 | 0.461 0.486 0.521 | 0.619 0.586 0.537 | 0.696 0.637 0.561 |

| Variable | Social Recognition | Perceived Value | ICH’s Authenticity | Cultural Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social recognition | 0.677 | 0.527 | 0.365 | 0.363 |

| Perceived value | 0.588 | 0.323 | 0.169 | |

| ICH’s authenticity | 0.838 | 0.046 | ||

| Cultural identity | 0.915 | |||

| CR | 0.92 | 0.784 | 0.738 | 0.775 |

| AVE | 0.536 | 0.421 | 0.364 | 0.466 |

| Path | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | Validation Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived value ←ICH’s authenticity | 0.393 | 0.090 | 4.370 | *** | Support |

| Perceived value ← Cultural identity | 0.239 | 0.094 | 2.543 | 0.011 | Support |

| Social recognition ← Perceived value | 0.723 | 0.141 | 5.137 | *** | Support |

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | BC/PC P–Value | BC | PC | |

| Indirect Effect | ||||

| Cultural identity→Perceived value → Social recognition | 0.173 | 0.071/0.122 | –0.023~0.391 | –0.060~0.365 |

| ICH’S authenticity → Perceived value → Social recognition | 0.284 | 0.001/.001 | 0.100~.613 | 0.100~0.613 |

| Direct Effect | ||||

| Cultural identity → Perceived value | 0.239 | 0.093/0.122 | –0.048~0.503 | –0.071~0.489 |

| ICH’S authenticity → Perceived value | 0.393 | 0.001/0.001 | 0.190~0.750 | 0.179~0.707 |

| Perceived value → Social recognition | 0.723 | 0.002/0.001 | 0.378~1.066 | 0.407~1.102 |

| Total Effect | ||||

| Cultural identity → Perceived value | 0.239 | 0.093/0.122 | –0.048~0.503 | –0.071~0.489 |

| Cultural identity → Social recognition | 0.173 | 0.071/0.122 | –0.023~0.391 | –0.060~0.365 |

| ICH’S authenticity → Perceived value | 0.393 | 0.001/0.001 | 0.190~0.750 | 0.179~0.707 |

| ICH’S authenticity → Social recognition | 0.284 | 0.001/0.001 | 0.100~0.613 | 0.100~0.613 |

| Perceived value → Social recognition | 0.723 | 0.002/0.001 | 0.378~1.066 | 0.407~1.102 |

| Item 1–6 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extract | Extract | Extract | |

| Diversity of Chinese culture | 0.532 | 0.487 | 0.606 |

| The authenticity of embroidery craftsmanship | 0.499 | 0.502 | 0.496 |

| The decorative arts of embroidery | 0.667 | 0.471 | 0.571 |

| Inheritance of embroidery skills | 0.503 | 0.446 | 0.577 |

| The history of embroidery culture | 0.431 | 0.431 | 0.624 |

| The seriousness of the decorative pattern | 0.657 | 0.631 | 0.731 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, W.-J.; Chiou, S.-C. The Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage from the Perspective of Civic Participation: The Informal Education of Chinese Embroidery Handicrafts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094958

Yan W-J, Chiou S-C. The Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage from the Perspective of Civic Participation: The Informal Education of Chinese Embroidery Handicrafts. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):4958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094958

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Wen-Jie, and Shang-Chia Chiou. 2021. "The Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage from the Perspective of Civic Participation: The Informal Education of Chinese Embroidery Handicrafts" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 4958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094958

APA StyleYan, W.-J., & Chiou, S.-C. (2021). The Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage from the Perspective of Civic Participation: The Informal Education of Chinese Embroidery Handicrafts. Sustainability, 13(9), 4958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094958