Impact of Experiential Value of Augmented Reality: The Context of Heritage Tourism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Experiential Value

2.2. Experiential Authenticity, AR Satisfaction, and Willingness to Support

3. Method

3.1. Measures

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

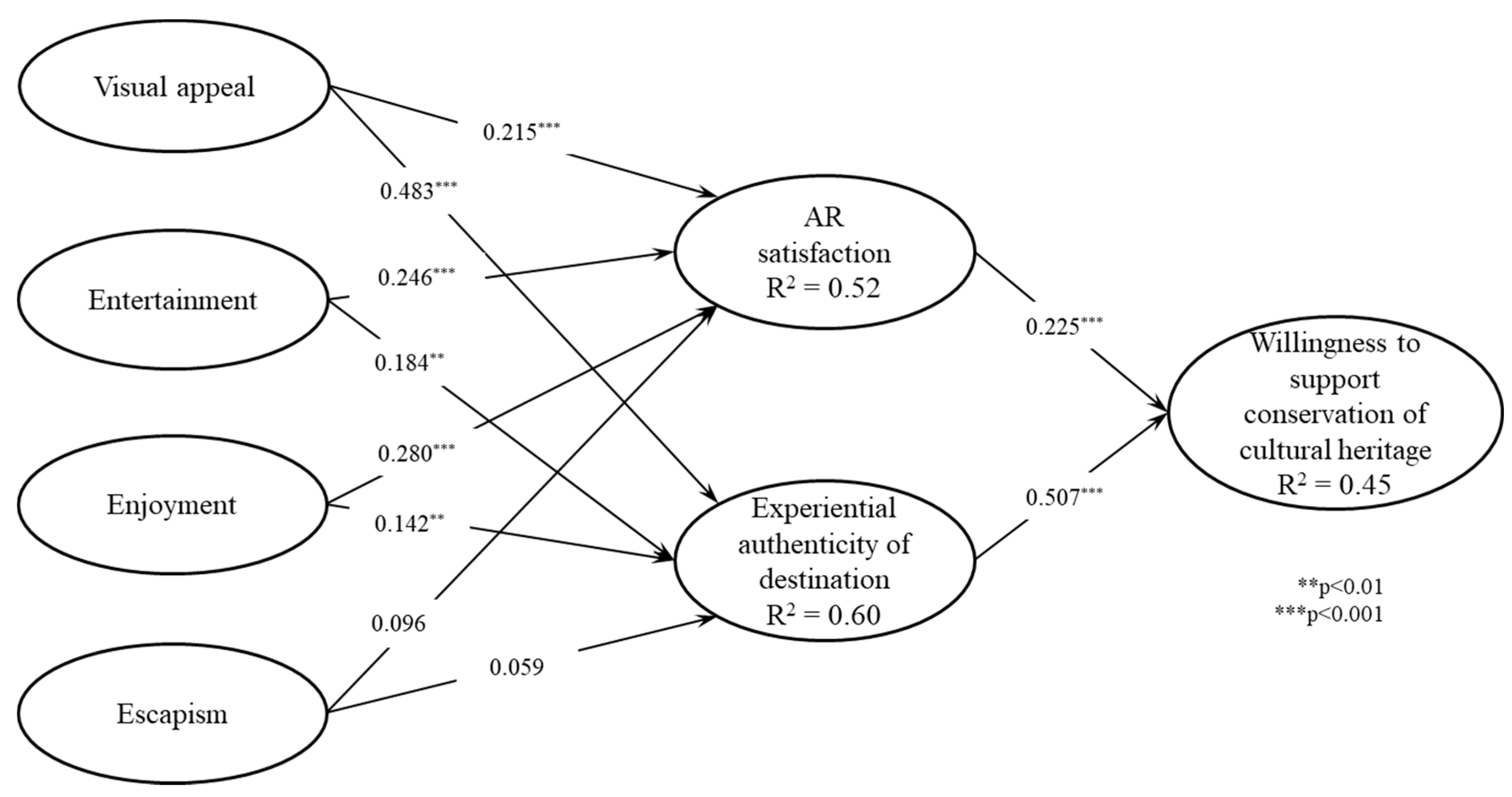

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tom Dieck, M.C.; Jung, T. A theoretical model of mobile augmented reality acceptance in urban heritage tourism. Curr. Issues. Tour. 2018, 21, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunfio, M.; Campana, S.; Magnelli, A. Measuring the impact of functional and experiential mixed reality elements on a museum visit. Curr. Issues. Tour. 2020, 23, 1990–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caton, K.; Santos, C.A. Heritage tourism on Route 66: Deconstructing nostalgia. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstetter, D.L.; Confer, J.J.; Graefe, A.R. An exploration of the specialization concept within the context of heritage tourism. J. Travel Res. 2001, 39, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Han, D. Augmented Reality (AR) in urban heritage tourism. E-Rev. Tour. Res. 2014, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Jung, T.H.; tom Dieck, M.C. Embodiment of wearable augmented reality technology in tourism experiences. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, J.; Edler, D.; Dickmann, F. Preparing the HoloLens for user studies: An augmented reality interface for the spatial adjustment of holographic objects in 3D indoor environments. KN-J. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. 2019, 69, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, C. From territory to smartphone: Smart fruition of cultural heritage for dynamic tourism development. Plan. Pract. Res. 2014, 29, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalay, Y.; Kvan, T.; Affleck, J. New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Trunfio, M.; Campana, S. A visitors’ experience model for mixed reality in the museum. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunfio, M.; Lucia, M.D.; Campana, S.; Magnelli, A. Innovating the cultural heritage museum service model through virtual reality and augmented reality: The effects on the overall visitor experience and satisfaction. J. Herit. Tour. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Jung, T.H.; Moorhouse, N.; Suh, M.; Kwon, O. The influence of mixed reality on satisfaction and brand loyalty in cultural heritage attractions: A brand equity perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Han, H.; Joun, Y. Tourists’ intention to visit a destination: The role of augmented reality (AR) application for a heritage site. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.Y.; Koo, C. The role of augmented reality for experience-influenced environments: The case of cultural heritage tourism in Korea. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathwick, C.; Malhotra, N.; Rigdon, E. Experiential value: Conceptualization, measurement and application in the catalog and Internet shopping environment. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wu, L.; Li, X.R. When art meets tech: The role of augmented reality in enhancing museum experiences and purchase intentions. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Lee, C.K.; Back, K.J.; Schmitt, A. Brand experiential value for creating integrated resort customers’ co-creation behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.T.S.; Wang, Y.C. Experiential value in branding food tourism. J. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.X.; Hsu, C.H.; Lin, B. Tourists’ experiential value co-creation through online social contacts: Customer-dominant logic perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 108, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.P. Augmented reality enhancing place satisfaction for heritage tourism marketing. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1078–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lo, H.P.; Chi, R.; Yang, Y. An integrated framework for customer value and customer-relationship-management performance: A customer-based perspective from China. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2004, 14, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.S.; Monroe, K.B. How buyers perceive savings in a bundle price: An examination of a bundle’s transaction value. J. Mark. Res. 1993, 30, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Lim, H.; Kim, Y.K. Experiential value: Application to innovative consumer technology products. J. Cust. Behav. 2013, 12, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keng, C.J.; Tran, V.D.; Le Thi, T.M. Relationships among brand experience, brand personality, and customer experiential value. Contemp. Manag. Res. 2013, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.H.E.; Wu, C.K. Relationships among experiential marketing, experiential value, and customer satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2008, 32, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R. Consumer self-regulation in a retail environment. J. Retail. 1995, 71, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B. The nature of customer value: An axiology of services in the consumption experience. In Service Quality: New Directions in Theory and Practice; Rust, R.T., Oliver, R.L., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; Volume 21, pp. 21–71. [Google Scholar]

- Maghnati, F.; Ling, K.C. Exploring the relationship between experiential value and usage attitude towards mobile apps among the smartphone users. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S. The product life cycle: Analysis and applications issues. J. Mark. 1981, 45, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, L.S.; Kernan, J.B. On the meaning of leisure: An investigation of some determinants of the subjective experience. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 9, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Monroe, K.B.; Krishnan, R. The effects of price-comparison advertising on buyers’ perceptions of acquisition value, transaction value, and behavioral intentions. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim Lian Chan, J. The consumption of museum service experiences: Benefits and value of museum experiences. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCole, P. Refocusing marketing to reflect practice: The changing role of marketing for business. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2004, 22, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallud, J.; Monod, E. User experience of museum technologies: The phenomenological scales. Eur. J. Inf Syst. 2010, 19, 562–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.I.; tom Dieck, M.C.; Jung, T. User experience model for augmented reality applications in urban heritage tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.I.; Jung, T.; Gibson, A. Dublin AR: Implementing augmented reality in tourism, In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2014; Xiang, Z., Tussyadiah, I., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 511–523. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work is Theatre & Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, F.S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, T.; Feldberg, F.; van den Hooff, B.; Meents, S.; Merikivi, J. Satisfaction with virtual worlds: An integrated model of experiential value. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Cheng, C.C.; Ai, C.H.; Wu, T.P. Fast-disappearing destinations: The relationships among experiential authenticity, last-chance attachment and experiential relationship quality. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 956–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerva, K. ‘Chance Tourism’: Lucky enough to have seen what you will never see. Tour. Stud. 2018, 18, 232–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Barreto, J.; Rubio, N.; Campo, S. Destination brand authenticity: What an experiential simulacrum! A multigroup analysis of its antecedents and outcomes through official online platforms. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, P.; Tavakoli, R.; Sharif, S.P. ‘Authentic but not too much’: Exploring perceptions of authenticity of virtual tourism. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2017, 17, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golomb, J. In Search of Authenticity: Existentialism from Kierkegaard to Camus; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Guo, J.; Wu, Y. Investigating the structural relationships among authenticity, loyalty, involvement, and attitude toward world cultural heritage sites: An empirical study of Nanjing Xiaoling Tomb, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trilling, L. Sincerity and Authenticity; Harvard University Press: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, K. Authenticity as a concept in tourism research: The social organization of the experience of authenticity. Tour. Stud. 2002, 2, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handler, R.; Saxton, W. Dyssimulation: Reflexivity, narrative, and the quest for authenticity in “living history”. Cult. Anthropol. 1988, 3, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, S.; Kim, A.K. Toward a framework integrating authenticity and integrity in heritage tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1468–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, J. Authenticity, authentication and experiential authenticity: Telling stories in museums. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2020, 21, 1245–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, G.T.; Goh, Y.N. Tourists’ intention to visit heritage hotels at George Town World Heritage Site. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Ahmad, M.S.; Petrick, J.F.; Park, Y.N.; Park, E.; Kang, C.W. The roles of cultural worldview and authenticity in tourists’ decision-making process in a heritage tourism destination using a model of goal-directed behavior. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Rivas, C.; Sánchez-Rivero, M. Willingness to pay for more sustainable tourism destinations in world heritage cities: The case of Caceres, Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wang, M.; Gao, X. Valuing tourists’ willingness to pay for conserving the non-use values of marine tourism resources: A comparison of three archipelagic tourism destinations in China. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 678–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonincontri, P.; Marasco, A.; Ramkissoon, H. Visitors’ experience, place attachment and sustainable behaviour at cultural heritage sites: A conceptual framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, S.; Zhang, H.; Mao, L.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y. How outstanding universal value, service quality and place attachment influences tourist intention towards world heritage conservation: A case study of Mount Sanqingshan National Park, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, N. Planning for urban heritage places: Reconciling conservation, tourism, and sustainable development. J. Plan. Lit. 2003, 17, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Quintero, A.M.; González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Paddison, B. The mediating role of experience quality on authenticity and satisfaction in the context of cultural-heritage tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, T.; Zabkar, V. A Consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Bendle, L.J.; Yoon, Y.S.; Kim, M.J. Thanatourism or peace tourism: Perceived value at a North Korean resort from an indigenous perspective. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.; Da Silva, D.; Bido, D. Structural equation modeling with the SmartPLS. Braz. J. Mark. 2015, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: London, UK, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theor. Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing, In New Challenges to International Marketing (Advances in International Marketing); Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Phillips, L.W. Representing and testing organizational theories: A holistic construal. Adm. Sci. Q. 1982, 459–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Weiler, B.; Assaker, G. Effects of interpretive guiding outcomes on tourist satisfaction and behavioral intention. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Fyall, A. Managing heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 682–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landorf, C. Managing for sustainable tourism: A review of six cultural World Heritage Sites. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Frequency (%) | Variable | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Education | ||

| Male | 233 (65.6%) | Below or high school graduate | 1 (0.3%) |

| Female | 122 (34.4%) | Some college/Technical or vocational school | 46 (13.0%) |

| Age | Four year college | 233 (65.6%) | |

| 18–24 | 8 (2.2%) | Post graduate degree | 75 (21.1%) |

| 25–34 | 226 (63.7%) | ||

| 35–50 | 87 (24.5%) | Marital status | |

| 50+ | 34 (9.6%) | Single | 40(11.3%) |

| Income | Married | 306 (86.2%) | |

| Less than $24,999 | 47 (13.2%) | Divorced/Separated | 1(0.3%) |

| $25,999 to $49,999 | 112 (31.5%) | Living with a same sex partner | 1(0.3%) |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 133 (37.5%) | Living with opposite sex partner | 7 (2.0%) |

| $75,000 to $99.999 | 47 (13.2%) | Widowed | 0 (0%) |

| $100,000 or more | 16 (4.5%) | ||

| Ethnic | |||

| White/Caucasian | 140 (39.4%) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 175 (49.3%) | ||

| Asian | 7 (2.0%) | ||

| Black/African-American | 23 (6.5%) | ||

| Other | 10 (2.8%) |

| Mean | SD | Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual appeal | 0.787 | 0.788 | 0.863 | 0.612 | |||

| The tourism environment of the (heritage site name) as seen through AR is quite attractive. | 5.752 | 0.784 | 0.806 | ||||

| The view as seen through AR is in harmony with the environment in the (heritage site name) | 5.932 | 0.856 | 0.709 | ||||

| The (heritage site name) as seen through the AR service is quite visually appealing | 5.873 | 0.855 | 0.777 | ||||

| The (heritage site name) view as seen through the AR application provided a way for users to easily experience it | 5.848 | 0.872 | 0.832 | ||||

| Entertainment | 0.657 | 0.657 | 0.814 | 0.593 | |||

| I think the heritage tourism experience with the AR is very entertaining. | 5.961 | 0.848 | 0.793 | ||||

| The enthusiasm of the heritage tourism with the AR is catching-it picks me up. | 5.766 | 0.881 | 0.747 | ||||

| The heritage tourism as seen through AR does not just displays heritage contents– it entertains me. | 5.823 | 0.925 | 0.769 | ||||

| Enjoyment | 0.792 | 0.793 | 0.865 | 0.616 | |||

| I am thrilled about having such an experience with the AR. | 5.854 | 0.941 | 0.782 | ||||

| I really enjoy this heritage tourism experience with the AR. | 6.000 | 0.843 | 0.768 | ||||

| The heritage tourism experience with the AR is exciting. | 5.856 | 0.881 | 0.782 | ||||

| I am indulged in the activities with the AR. | 5.837 | 0.911 | 0.806 | ||||

| Escapism | 0.819 | 0.829 | 0.893 | 0.735 | |||

| Having such heritage tourism experience with the AR gests me away from the vexations and pressure of real life | 5.758 | 1.079 | 0.889 | ||||

| Having such heritage tourism experience with the AR makes me feel like I am in another world. | 5.761 | 0.929 | 0.801 | ||||

| I get so involved when I have the heritage tourism experience with the AR that I forget everything else. | 5.825 | 1.042 | 0.879 | ||||

| Authenticity | 0.759 | 0.76 | 0.847 | 0.58 | |||

| During the visit to (heritage site name), I felt related to the history of (heritage site name). | 5.744 | 0.852 | 0.789 | ||||

| I liked the way this (heritage site name) was designed. | 5.997 | 0.837 | 0.767 | ||||

| The overall sight and impression of (heritage site name) inspired me. | 5.938 | 0.873 | 0.73 | ||||

| I enjoyed the unique experience of (heritage site name). | 5.992 | 0.785 | 0.76 | ||||

| Satisfaction | 0.845 | 0.847 | 0.896 | 0.682 | |||

| I am satisfied with the quality of information provided by the AR. | 6.039 | 0.8 | 0.844 | ||||

| I am satisfied with the visual interface design (such as graphic) of the AR. | 5.997 | 0.785 | 0.81 | ||||

| The AR service makes my tourist experience more interesting. | 5.941 | 0.842 | 0.815 | ||||

| I like using the AR service as part of the (heritage site name) visit. | 6.07 | 0.768 | 0.833 | ||||

| Will | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.867 | 0.685 | |||

| I will support the conservation of (heritage site name). | 5.924 | 0.803 | 0.865 | ||||

| The conservation/sustainable development of (heritage site name) is the right choice for cultural heritage tourism | 6.054 | 0.836 | 0.793 | ||||

| The future of (heritage site name) should be conserved in an appropriate way. | 6.028 | 0.845 | 0.823 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual appeal (1) | 0.782 | ||||||

| Entertainment (2) | 0.677 | 0.770 | |||||

| Enjoyment (3) | 0.717 | 0.666 | 0.785 | ||||

| Escapism (4) | 0.523 | 0.599 | 0.554 | 0.857 | |||

| Authenticity (5) | 0.742 | 0.644 | 0.647 | 0.504 | 0.762 | ||

| Satisfaction (6) | 0.632 | 0.635 | 0.651 | 0.51 | 0.627 | 0.826 | |

| Willingness to support (7) | 0.586 | 0.539 | 0.531 | 0.398 | 0.645 | 0.546 | 0.828 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, S.; Yoon, J.-H.; Kwon, J. Impact of Experiential Value of Augmented Reality: The Context of Heritage Tourism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084147

Han S, Yoon J-H, Kwon J. Impact of Experiential Value of Augmented Reality: The Context of Heritage Tourism. Sustainability. 2021; 13(8):4147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084147

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Seokho, Ji-Hwan Yoon, and Jookyung Kwon. 2021. "Impact of Experiential Value of Augmented Reality: The Context of Heritage Tourism" Sustainability 13, no. 8: 4147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084147

APA StyleHan, S., Yoon, J.-H., & Kwon, J. (2021). Impact of Experiential Value of Augmented Reality: The Context of Heritage Tourism. Sustainability, 13(8), 4147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084147