Abstract

Since 2017, the State Office for Nature, Environment and Consumer Protection of North Rhine-Westphalia (LANUV) has established an operational environmental and sustainability management and set specific objectives to reach operational carbon neutrality. In this context, central questions aim at the availability of financial and human resources, the competition with other duties as well as the necessary involvement of the staff. Based on the practical example of LANUV, this article presents concrete activities, e.g., in context of mobility or human resources, as well as the challenges connected to them. While single measures do have a positive impact, a structural approach, like the set-up of an environmental management system (e.g., EMAS—Eco-Management and Audit Scheme), is found to be more effective. In addition, success factors are identified such as distinct structures and responsibilities, a capable person in charge of the process, and commitment on the management level, as well as challenges like the lack of governmental objectives and obligations or limited human and financial resources. This article follows the idea of a case report in a transdisciplinary manner, presenting ideas for enhancement and shedding a light on a possible spread of sustainability endeavors to other national institutions.

1. Introduction

The necessity to design processes in the public administration in terms of sustainable development is obvious. This necessity results from political objectives, the role model function for companies and the civil society, the influence on ecological and social aspects as well as the market power of public procurement. The importance of sustainability and climate neutrality is also evident in the current sustainability strategy as well as in the climate protection laws at the federal and state level in Germany. This groundwork ties in with international agreements such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Climate Agreement, as well as the federal strategies. The federal level provides guidance with regard to activities in the federal administration.

In 2010, the State Secretaries’ Committee for Sustainable Development in Germany implemented the program of sustainability measures, being regularly evaluated and updated, and high priority is given to a sustainable administration on the federal level in the sustainability strategy of Germany of 2021 [1]. At the state level, the relevance of a sustainable administration was made clear in the sustainability strategy of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) in the year 2016, and the topic remains important in its update in the year 2020. The strategy states that actions in the state administration shall be in accordance with sustainability criteria. Sustainability strategies, overarching sectors on an operational level and generations on a temporal level, are regarded as essential if this topic is to fully arrive in the public administration [2].

In addition, since the passing of the Climate Protection Law in 2013, the state government committed itself to turn the state administration climate-neutral by 2030 [3]. The state administration of NRW currently emits around 350,000 tons of CO2 annually through buildings, car pools, and business trips [4], which shows the enormous saving potential. In order to coordinate the activities in the state administration, a “Climate-Neutral State Administration Office” was set up in the Ministry of Economic Affairs, Innovation, Digitalization and Energy. On the federal level, the Coordinating Office for the Climate-Neutral Federal Administration (KKV) was founded in 2020, which is located in the Federal Ministry for the Environment [5].

A focus in Germany lies on the local level as relevant actor as well, since one idea of the Agenda 2030 was to connect territorial development to sustainability [6]. Although the introduction of Local Agenda 21 Processes started in Germany late in the mid ‘90s, it did not really persist in most cities. However, the relevance of climate protection activities in cities arose in the beginning of the 2000s as a central task for humankind [7,8,9]. The federal government in Germany fostered this central role by public funding for implementation of climate protection strategies [10].

Despite these initiatives, only few activities have been carried out so far in administrations of the state of NRW, promoting sustainable development or even, in the best case, developing a systematic sustainability management. In addition, literature on the implementation of sustainability management affecting strategic and operational activities in the public sector is highly limited [11,12]. For the most part, scientific studies on sustainability management either deal with an implementation on a local level [13,14] or within businesses [15,16,17]. Furthermore, the discussion focuses on the implementation of sustainability as policy for society or a policy field [18,19].

In consequence, a central question is how to introduce sustainability not only on a level of policy but also on an operational level. Having a look at European neighbors, Braun shows for the Swiss State that sustainability is a relevant issue, but not addressed in a systematic way [20]. In Portugal, public administration integrated social and economic sustainability criteria to some extent, but showed a lack of the ecological aspects [12]. In public healthcare, Italy focuses on compliance with laws and restrictions while the UK is heading towards an integration of more eco- and climate-friendly criteria [21].

In Germany, at least the sectors’ finances and procurement made progress in that regard. The Competence Center for Sustainable Procurement at the Procurement Office of the Federal Ministry of the Interior (KNB) supports all public clients in considering sustainability criteria in procurement projects [1]. This has been an important step, as it has a particularly high potential to change the sustainability performance of an institution, because each procured product and every service has a value chain that influences the ecological and social environment on its way to the office [22].

Furthermore, in the Federal Academy for Public Administration (BaköV), a sustainability education office has been set up, which supports executives and employees of the federal authorities with adequate training in order to manage sustainability-related challenges [23].

In addition, different institutions offer support for reporting about the sustainability performance, like the Global Reporting Initiative, The Sustainability Code (DNK), and ÖKOPROFIT®. The latter is a comparatively simple, low-threshold entry to start with environmental management. Within the one-year-long project, institutions get support on their way to develop measures by means of a combination of workshops and individual consultancy. Another central element is the calculation of profit—both from an environmental and an economic point of view. The project ended with an award and a publication about the project activities. In NRW, the profit from 182 implemented ÖKOPROFIT® projects amounted to total savings of about 320,000 tons of CO2 and over 80,000€ [24].

However, in order to address all aspects of sustainability on the operational level, a systematic approach is essential, implying the introduction of management systems. The business perspective on a corporate sustainability management is a central element in that regard, presenting key elements such as “systematic activities to measure, analyze, improve and communicate economic, social, and environmental aspects of a company“ [16] (p. 2384).

Corporate sustainability management systems for the environment can be based on established systems like ISO 14001 or EMAS. These environmental management systems are regularly checked within an external audit. The business develops a permanent management structure in the sense of a Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle. Further instruments are essential for institutions (core indicators, goal setting, development of measures, management review, etc.) to monitor, improve, and report on indicators and measures. The EMAS-System especially sets transparent external communication as mandatory [25]. Thus, elements of the administrative reforms can be found here, such as “new public management” (impact measurement) and “the approach of cooperative administration” (participation of employees, reporting, and stakeholder involvement) [26].

The integration of the social and economic dimension in a continuous improvement process is not as widespread as EMAS or ISO 14001, though. EMASplus (externally verifiable in Germany) or the “Guidance on social responsibility” (ISO 26000) include this broader perspective. Moreover, there are basic approaches that focus on corporate climate protection. For example, ISO 14064 specifies the framework for transparent quantification and monitoring of greenhouse gas emissions, adequate reporting, as well as the recording of progress regarding reduction efforts. It is based on the international standard of the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHGP), which details the data acquisition and bindingly prescribes at least a balancing of the areas of direct emissions (building heating and cooling, vehicle fleet) and indirect emissions (electricity, district heating).

In addition, there is a concept that introduces climate management in companies as an extension of EMAS in order to use synergies and to establish a uniform test basis and “minimum requirements for credible climate management” [27]. The introduction of an energy management system according to ISO 50001 also offers approaches for a structured improvement, helping to monitor and reduce power consumption. Furthermore, a structured quality management system according to ISO 9001 or ISO 17025 offers connection options for the integration of elements from the areas of sustainability management and, particularly, environmental management.

Although a specific management system for public administrations does not exist, the circumstances detailed before show the need for adopting such a management system. Hence, the questions arise how the necessary changes can be achieved in institutions of the state administration and how a general embedding of the sustainability concept in each branch can be ensued. Heinrichs and Schuster conclude, “the sustainable development as a socio-politically negotiated topic [...] has not yet been accompanied by adequate administrative routines in the administrative multi-level government system in Germany” [26] (p. 206). With regard to administrative reforms, they assess both the “new management model” and the “approach of cooperative administration” as relevant for the orientation towards the principle of sustainable development in public administration institutions. Business approaches, transparency, and participation shall strongly be taken into account. Furthermore, they are of the opinion that “further development of state institutions in the sense of a systematic, sustainability-oriented administrative reform program with organizational structural, procedural, cultural, and instrumental approaches is to date hardly noticeable” [26] (p. 205). Figuiera et al. emphasize the need “to invest in the sustainability training and engagement of the employees, managers and decision-makers” [10] (p. 625) to foster a rollout of sustainability management in public sector organizations.

Furthermore, the Federal Environment Agency states that the key to success lies in the “intensive and frank communication, the necessary transparency in the structuring of superior processes, the development of key figures and guidelines, the creation of administrative basics, the creation of the financial bases in the budget, the continuous work on obstacles, a critical self-reflection, and the participation of every individual in this process” [28] (p. 6). Scientists from the Wuppertal Institute argue similarly with a view to the sustainable state administration of North Rhine-Westphalia. This goal from the NRW sustainability strategy can be reached, if not only selective activities are implemented, but a comprehensive anchoring takes place. Therefore, a systematic management approach should primarily be used. Accordingly, the support of the state government and a cabinet resolution are required, obligating the state authorities to introduce a sustainability management. This goes hand in hand with the need to ensure an adequate range of resources [29].

This article presents the activities establishing an operational sustainability management in one German state institution, the State Office for Nature, Environment, and Consumer Protection NRW (LANUV). It was carried out within the project “Sustainable Administration of the Future”, which was highlighted in the NRW sustainability strategy as a model project [30]. The case report follows the idea of transdisciplinary and transformative sustainability research as described by Heinrichs et al. [31]. The authors do not work in a method driven way like, e.g., Wiek and Lang [32], but present their experiences gathered by implementation. The LANUV serves as an example to demonstrate and clarify the “organizational structure and the procedural, cultural, and instrumental approaches” [29] (p. 205) as well as relevant success factors and inhibiting aspects, offering an example for a possible spread to other institutions as well. By shedding a light on the practical perspective, the report intends to add key elements to the scientific discussion about an operational sustainability management within a public administration on the state level.

2. Implementation

The LANUV is a state office and the technical and scientific authority of the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia for nature, environment, and consumer protection, and employs about 1400 people. It is subordinated by the Ministry for the Environment, Agriculture, Nature, and Consumer Protection of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia and advises the state government. Even though the NRW sustainability strategy set up the framework for working towards a sustainable and climate-friendly future, presenting the SDGs in a regional context, the LANUV started being active in corporate environmental responsibility and climate neutrality out of a strong self-image years before that. First, single measures and initiatives were implemented. In the year 2014, several employees formed the Working Group Green Spaces as a project to protect and promote biodiversity on the grounds of the institution. Being backed by the top management, the idea is to allow members of the group to spend several working hours every few months to develop ideas, try to implement these ideas, or to communicate them with the responsible work units. Being no mandatory task for the LANUV, there is no budget for the Working Group. Because of that, measures requiring a budget are only realized if the relevant work units are convinced and do have the financial and human resources to do so. These circumstances often lead to long processing times and impair progress.

On the other hand, with climate change and climate protection being some of the most relevant issues in Germany for at least the last decade, the LANUV was chosen to become a model institution, aiming to emit no more CO2 or compensate the remainder in the near future. The LANUV introduced the strategy for climate-neutrality in 2014 as well. In this case, personnel and financial resources are available, enabling a regular reporting and a measure-based reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. One of the first steps was the “missionE” campaign that raised awareness among the employees for energy-saving behavior at the office. Apart from a necessary workshop for the responsible actor to prepare implementation, the measure is easy to implement and has low costs. Having a skilled person in charge and the workforce on board did result in energy savings of more than 10%.

Furthermore, the LANUV gradually improved its social sustainability over the last years by means of various measures to improve the satisfaction among the employees and to raise the attractiveness as an employer. Despite these early efforts, there was a wish to expand the measures supporting SDGs and to systematically monitor and report on the progress, all related to the NRW sustainability strategy being released in 2016. Additionally, since all these measures stood by themselves, an integration into one system seemed helpful. It triggered the development of a systematic sustainability management as a model project for the state administration NRW and an application for funding its implementation in the LANUV was submitted. The resulting project “Sustainable Administration of the Future”, which was financially and technically supported by the German Federal Environment Foundation as well as by funds from the LANUV and the Ministry for Environment, Agriculture, Conservation and Consumer Protection, was carried out from April 2017 to July 2019. The project funding enabled the LANUV to employ additional staff for planning and implementing activities and realizing the following objectives:

- the conception of a sustainability management with EMAS core elements including a realization and implementation plan for the introduction of the sustainability management,

- developing blueprints for other institutions for the implementation of the sustainability strategy,

- the exemplary implementation of single measures,

- the intensive participation of the employees,

- the increase in attractiveness as an employer.

In the following, the involvement of the staff is detailed, not only because it is a core EMAS element, but because previous activities in the LANUV heavily relied on that factor and new measures were derived from this. Thereafter, the management system implemented in the LANUV is described. Finally, this chapter details the measures and projects implemented in various fields of action relevant for sustainability and climate neutrality.

2.1. Involvement

As a first step, information on the planned activities in the project and on climate-friendly and sustainable activities in everyday work was distributed in many ways, e.g., via events, posters, and the intranet. The involvement of the employees themselves has been considered important for two reasons: For one, far-reaching changes, as for instance in the classic change management, need to be borne by many, and for another, the co-creation of the change increases the acceptance of the process. Furthermore, the technical expertise on sustainability issues is particularly high. In order to use and link these potentials, various formats have been developed, such as a leader’s conference on operational sustainability, several employee forums for information and participation, and an online survey on advice and opinions.

Based on the results, a large number of thematic workshops with employees and persons responsible for the subject areas were carried out, jointly defining potentials for improvement and concrete measures. For continuous participation, the LANUV introduced an idea management system, allowing the employees to submit suggestions that the relevant work units check and implement, if possible. Suggestions and comments were presented openly, allowing for maximum transparency and impulses for improvement.

2.2. Management System

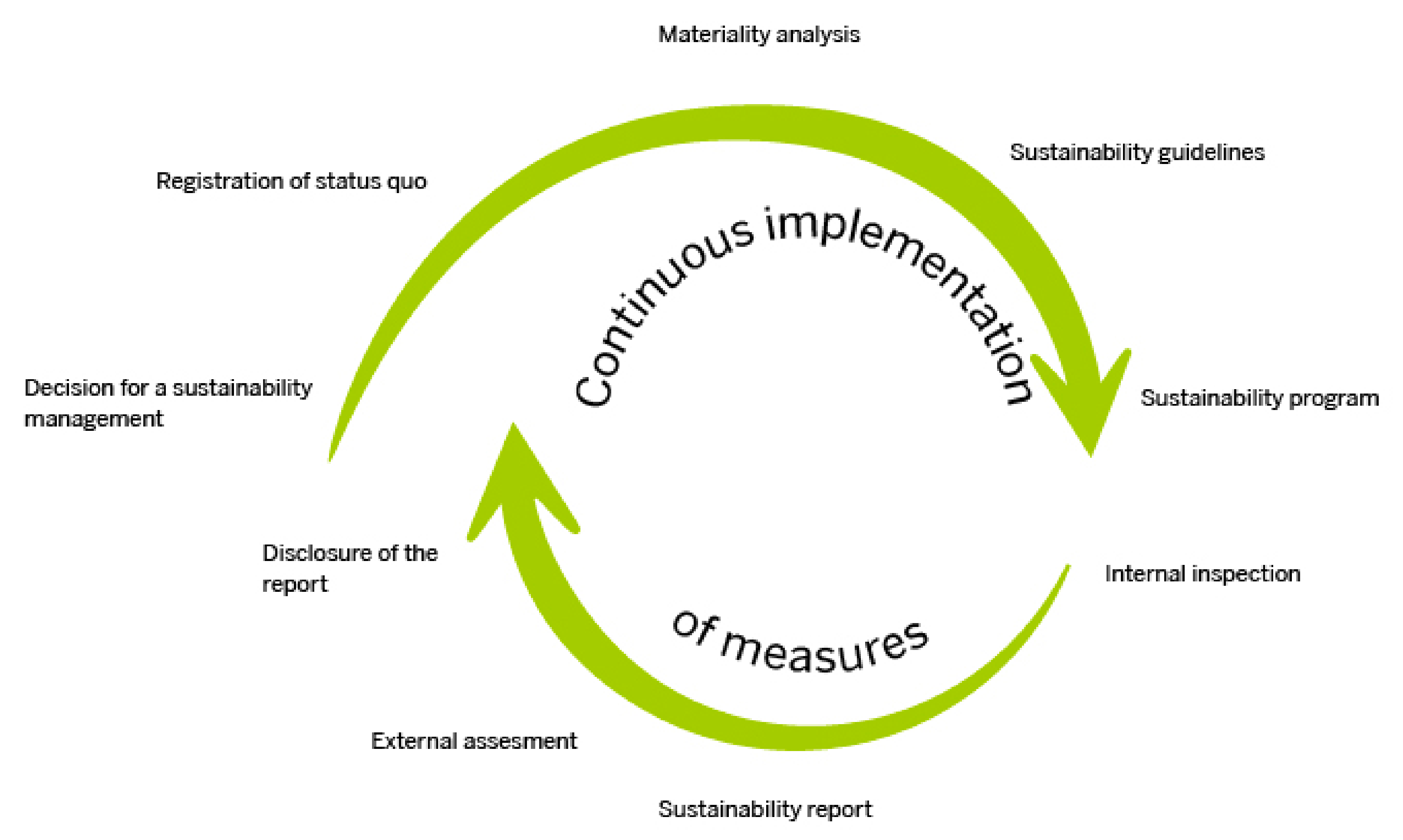

The communication and participation were the starting point on the way to a systematic management system. Moreover, the groundwork for continuous improvement is to run a stakeholder analysis, identify direct and indirect aspects, and relevant measures. Accordingly, the LANUV management system should enable continuity and constant improvement. Within the management system, several instruments were established. Figure 1 gives a summary of the steps that shall ensure the continuous improvement process in the sustainable administration.

Figure 1.

Overview on the various steps regarding the process of continuous improvement.

The concept for sustainability management in the LANUV is especially oriented towards the EMAS elements and takes into account the requirements of ISO 26000, as the aforementioned aspects regarding continuous improvement show. Furthermore, the LANUV intends to make use of synergy effects, integrating sustainability and quality management according to DIN ISO 9001 and 17025 into a joined-up management system.

For a solid basis, a large number of guidelines, literature, and external experience from comparable institutions was obtained and internal members of the sustainability team were qualified in training courses to become sustainability managers and auditors.

The organizational structure of the operational environmental and sustainability management of the LANUV considers the various existing initiatives and activities in the LANUV and shall enable broad participation on the employee side. Therefore, the working group “Environmental and Sustainability Management” complemented the management structure of the sustainability team and the steering group already established in the project. These three committees undertake the tasks relevant for the management system and publicize the content to the entire LANUV. The structure corresponds to the overview in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Organizational structure of the environmental and sustainability management within the LANUV with its three committees.

The central component of environmental and sustainability management is the environmental and sustainability program, documenting the continuous improvement according to the measures implemented and the achieving objectives. The steering group, consisting of top management with a selection of relevant managers, approves it. Operational indicators have been developed in order to measure and document improvements. To achieve better connectivity, it goes back on the relevant standards like the EMAS core indicators, the “standards” of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), and The Sustainability Code (DNK). The guidelines for environmental and sustainability management, adopted by the steering group in the LANUV beforehand, serve as a higher-level framework, a core element to all ISO management systems.

A working group for operational environmental and sustainability management (approximately 25 members) supports the sustainability team in implementing the management system in the institution. During a compliance audit, the compliance with legal provisions was checked and suggestions for improvements formulated. The environmental assessment was carried out together with inspections and an assessment of relevant environmental aspects. Finally, the environmental and sustainability program with specific measures was derived therefrom and approved by the house management.

In 2020, an external auditor conducted an external review according to the EMAS regulation.

2.3. Flanking Projects and Measures

Following up the NRW sustainability strategy, five fields of action were defined. These are the topics: mobility, canteen operations, building and property management, procurement, and personnel management and development. In this regard, the activities for the climate-neutral LANUV are considered as an additional crosscutting issue. Those action fields are relevant areas for the sustainability management of the LANUV.

The aforementioned workshops proved the urgency for implementing concrete measures. The lack of personnel capacities and financial resources resulted in the need to acquire further financial support and project funds. Hereafter, measures and projects are explained in detail and the challenges are shown that administrations face during the implementation phase.

2.3.1. Mobility

Mobility is an important precondition for day-to-day operations. On the one hand, it is indispensable for carrying out daily tasks—from traveling to and from the workplace up to business trips. On the other hand, mobility also has a significant impact on the environment and human health. The endeavors in the context of a climate-neutral LANUV have resulted in the procurement of natural gas and electric vehicles as well as the provision of charging points for employees’ and visitors’ cars. In total, almost one fourth of the entire fleet runs without petrol or diesel, 13% using natural gas and 10% being electric vehicles. However, a procurement of these cars is only possible if the state NRW has certain contracts for them and even if so, there is no obligation to buy them.

Later, as part of an initiative of the sustainability team, principles for eco-friendly business trips, e.g., prioritization of rail travel versus flights and the check to avoid business trips by means of alternative communication tools such as video conferences, were drawn up, urging employees to follow them. While being a free measure, the approval of the top management is essential for implementation. Nevertheless, unavoidable business trips by plane, public transport, or private car have been fully compensated in the LANUV since 2019, although only with extra funding as there is usually no budget for state institutions in that regard.

With the instruments of home office, mobile work, and flexible working hours, the personal situation of the employees is also taken into account and the avoidance of travel journeys is promoted, which supports decent work conditions and gender equality at the same time. In addition, the LANUV supports health-promoting mobility by means of bicycle campaigns of the workplace health management. On top of that, two projects have been initiated in the LANUV that promote environment-friendly mobility—the project “Commuter Portal” as well as the project “Sustainable Optimization of Operational Mobility (NOMO)”.

Due to the difficult accessibility of some offices as well as frequent car use out of private reasons, the sustainability team initiated the establishment of a carpooling center and implemented the project “Commuter Portal” with the financial support of the Ministry of Economic Affairs, responsible for climate protection. Since 2018, the offer has been gradually expanded to the entire environmental and economic department and an expansion to other departments of the state administration is currently being prepared. The introduction phase of the commuter portal was accompanied by the regular provision of information and an intensive communication with the employees of the relevant institutions as potential users, which led to an increased interest in the platform. Now, more than 100 employees use the commuter portal regularly, which led to savings of more than 4,500,000 km and more than 650 tons of CO2 in total. A current challenge in expanding the commuter portal to the entire state administration is the fulfillment of special requirements of statewide IT systems with regard to data protection and accessibility.

Moreover, a saving of trips to work by car can also be achieved by increasing the attractiveness of environmental-friendly mobility alternatives or by promoting digital communication. Hence, the LANUV successfully took part in the competition “Mobile Wins” of two federal ministries with its mobility concept and was awarded as prizewinner in the category “large company”. Subsequently, the sustainability team and the responsible in-house departments implemented various specific measures as part of the project for the sustainable optimization of corporate mobility. These measures included, for example, analysis of mobility data, the procurement of video conference systems, the expansion of the bicycle infrastructure through more parking facilities and business e-folding bikes, departure monitors for public transport, and action days on the subject of mobility.

The project managers established this variety of measures successfully and the employees used the offers actively. However, the implementation of some other measures was either opposed to the legal framework of the state administration or did not lay in the competence of the sustainability team, hence resulting in a very high level of coordination effort. Additionally, these other actors are often bound by external factors, for example by the regulations of the property owner (e.g., in case of building new bicycle parking facilities) or the IT strategy of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, complicating or even stopping the implementation.

2.3.2. Canteen Operation

At the different locations of the LANUV, there are both canteens operated by external companies and external catering at events. As part of the employee participation, demands were made to make both as sustainable and climate-neutral as possible. This is challenging for company canteens in public institutions, as they already need to adapt the range of food to customer requirements, provide sufficient quantities at a reasonable price, and be profitable at the same time. As a result, the LANUV has started to address these issues by launching the project “Sustainable Nutrition and Avoidance of Food Loss in Canteens”. The project had the purpose of implementing a food low-loss canteen operation and a sustainability management, including an annual data collection. This concept should be transferable to other canteens of the state administration.

Therefore, the LANUV defined requirements for tender offers, including the sectors sustainable nutrition and food losses, the increased use of regional and seasonal food, the reduction in fat and sugar content, and the avoidance of single-use items. Besides these aspects, the tenders agree to offer a vegetarian dish and a low-price dish with a small portion.

The good cooperation between sustainability team, canteen committee, and tenants resulted in several additional activities, e.g., communication measures on food waste, targeted menu planning, use of surplus production, and provision of reusable take-away boxes. The canteen committee, established in 2018, fosters the communication between the LANUV, the tenants, and the employees.

Finally, bit by bit a sustainable and climate-friendly thinking sinks in, as the particularly high demand for vegetarian and vegan dishes shows, for example. Now, in case of planned tenders, other federal state authorities can also draw on the experience of the LANUV and a sample tender specification. Indeed, challenges arose as well, e.g., the staff needing the information and skill to collect relevant data for the various indicators at the different locations, changes in tenants, staff turnover and shortage. On top of that, the declining amount of portions because of home office during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 created difficulties for the canteens.

2.3.3. Building and Property Management

This field of action refers to the management of all buildings and properties used in many different ways, e.g., as offices, laboratories, or measuring stations. It also includes the planning of construction measures as well as the design of outdoor areas. Since the state of North Rhine-Westphalia owns more than 4000 buildings and additionally rents several hundred more, it shows the possible scale of impact measures could have here.

In this regard, it is most important to reduce energy and water consumption, to optimize waste quantities and separation, and to contribute to the preservation and promotion of biodiversity on the outside area. With regard to all activities in the field of building and property management, the LANUV acts dependently as a tenant, but has to closely coordinate with the proprietors.

Some concrete activities have already been introduced or are currently at work:

- the Working Group Green Spaces with an agenda to continuously design the outside areas of the LANUV closer to nature and to therewith support the biodiversity,

- missionE as a campaign to sensitize employees to electricity and heat consumption and to therewith reduce CO2 emissions,

- using standards for sustainable buildings, like the German Standards BNB and DGNB for new LANUV buildings (e.g., photovoltaic, rainwater use, green rooftops, accessibility precautions),

- public charging points for employees’ and visitors’ electric cars and a photovoltaic expansion at one location,

- the development of the waste management concept for the three main LANUV locations and the associated reorganization of the waste collection and disposal.

Within this field of action, many units are involved, leading to either a boost or a hindrance in the implementation. Because most of these activities lead to immediate savings or amortize themselves over time, the implementation can often be realized just with budget funds of the LANUV. On the other hand, cooperation and coordination effort is often high, as the proprietor, the internal service department, and other actors are usually involved, rendering an approach on own initiative impossible. For example, in the case of the successful implementation of a waste management, the sustainability team, the experts in the LANUV for waste management, the internal service department, and a consulting company worked together. In order to be successful, it was also necessary to include the working units responsible for special types of waste as well as the workforce. Extensive communication by mail, the intranet, and information days as well as the provision of the required infrastructure were key factors here, enabling waste separation in the offices in order to achieve a better separate collection rate and to avoid misthrows. In addition, the greatest challenge for implementation was the extensive preparatory work on the legal framework conditions as well as the communication with specialist departments and cleaning staff. However, first measurements showed that the separate collection rate was indeed increased and therewith the proportion of the amount of waste that can be recycled. Following standards and determining clear responsibilities helped achieve that goal.

2.3.4. Procurement

The LANUV orders goods and services worth approximately 35 million euros per year. Moreover, about 1500 services (procurement processes over 500 euros) are outsourced annually. The entire public administration in North Rhine-Westphalia invests about 50 billion euros annually for goods, construction, and services, a potential that can even change established market structures. So far, only first signs of improvement in terms of climate protection and sustainability are visible, such as the preferred procurement of energy-efficient products and services as one climate protection measure [33], which the LANUV has already integrated.

In order to achieve a better environmental impact for the house, sustainability criteria have to be established that procurement processes are aligned with. For this purpose, training and information for the work units responsible for procurement as well as a change of the standards and guidelines in terms of sustainable and climate-friendly procurement have been implemented.

In certain sectors, more demanding ecological criteria were included in the tenders, e.g., in public relations work. These include increasingly paying attention to paper from recycled resources or sustainable forestry and climate-neutral printing, often favoring “Blauer Engel” certified products, a German environmental certificate. Moreover, the sustainability team provides support in researching the sustainability aspects of specific products.

The successful implementation of the measures mentioned has indeed resulted in an improved environmental impact of the LANUV within this field of action. Furthermore, the ecological criteria in the tenders evoke an awareness of environmentally friendly procurement in the procurement offices. However, due to the legal framework the public administration is subject to, the procurement is only changeable to a limited extent. Other criteria, such as the price, remain by law crucial for the selection of goods, services, and construction works.

2.3.5. Personnel Management and Development

This field of action deals in particular with the responsibility as an employer towards the employees. That includes support in career development, equal opportunities, appreciation, health-maintaining working conditions, work-life balance, and much more. Some aspects are mandatory by law and the LANUV has established processes to address them. These include an employee representation, wage agreements with trade unions, minimum wage requirements in procurement, equalization, and inclusion. These aspects guarantee a high standard and address relevant SDGs in that field. Nevertheless, sustainability management considers these aspects as well and aims for continuous improvement.

Others aspects are voluntary. Those activities are of great importance contributing to the attractiveness as an employer, raising motivation and skill level among the workforce. Because of the good groundwork already established here, the sustainability team was mainly active in the sense of linking various areas and using synergies, which has not been done before without a systematic management.

Some implemented measures should be highlighted. On the one hand, this is the workplace health management, which contributes to reducing mental and physical stress at the workplace by means of in-house sports activities, bicycle campaigns, and by providing information on health-related topics, which is highly appreciated by the staff. On the other hand, as a certified family-friendly employer, the LANUV has and is implementing 30 measures to continuously improve the compatibility of work and family, like new models of home office or flexible working hours. Furthermore, a program for personnel development for specialists and managers (PE-FF) experiences high registration numbers and was successfully run two times now. This tailor-made support program for junior staff as part of an internal training program serves to improve and optimize the personal qualifications of the participants. Moreover, regular employee surveys are carried out and the results therefrom are used to deduce further measures, which are checked in follow-up surveys. There are also offers that are aimed to support the employees beyond work, like social contact persons helping the workforce to cope with problems and a parental network offering opportunities for activities and exchange for working parents.

2.4. Considering the SDGs

Although the activities within projects and established processes in the LANUV focus on a multiplicity of SDGs, not all SDGs are addressed, because the institution is bound to defined tasks and has limited influence on several areas. For example, the LANUV as a state administration does not create sustainable infrastructure (SDG 9), foster sustainable cities (SDG 11), or take measures for ocean protection (SDG 14) itself. For some SDGs, however, the LANUV can intensify its efforts and cover more aspects of specific SDGs.

Nevertheless, the measures taken influence the aforementioned SDGs in an indirect way. For example, promoting sustainable mobility affects the expectations and the behavior of employees, who are inhabitants of a city at the same time. In consequence, they may influence local political decisions in a long perspective, whether indirectly, e.g., by using the bicycle more often or directly, e.g., by addressing the city authorities to improve infrastructure in this regard. Another example would be the primarily procurement of fish only from sustainable fishing and the measures to reduce food loss in canteen operations, contributing to the conservation of the oceans. Table 1 presents the direct and indirect influence certain measures have on the SDGs.

Table 1.

List of implemented measures and their associated SDGs. Several measures do contribute to more than one SDG.

There are further activities that indirectly influence the performances, improving the SDGs on an operational level. However, the LANUV also addresses plenty of SDGs directly by their core functions, e.g., the promotion of education for sustainable education, the collection and evaluation of data about the state of environment as well as the derivation of new concepts and actions from these efforts.

3. Results and Discussion

Many advices in guidelines and experience reports on the implementation of environmental, climate, or sustainability management in the administration are related to local government (e.g. [34,35]). However, the framework conditions in the state administration differ in several respects from the examples documented so far, therefore often not allowing a 1:1 transfer. For example, the aspect of citizen participation in the state administration is far less important than at the municipal level, and the organizational and decision-making structure differs considerably. Hence, an involvement of stakeholders in sustainability reporting and the resulting improved policy-making like, for example, in Italian cities [36], is simply not applicable here. A comparison with management approaches in commercial enterprises is also not easily possible, because in the administration, the product orientation is often much less pronounced, there are stronger dependencies on higher-level structures, and the stakeholders and their demands are different [37]. Based on the experience of the LANUV, Table 2 shows important success factors and inhibiting framework conditions for the implementation of measures and the continuous development of a sustainability management within a public administration on state level. Some inhibiting conditions arise from the opposite of a success factor.

Table 2.

Overview about the success factors and inhibiting framework conditions for sustainability management in state administration.

In the following section, the above-listed aspects are explained in more detail, additionally being flanked by findings from a report on action implications for the sustainable public administration in North Rhine-Westphalia by Schostok et al. of the Wuppertal Institute, which is largely based on the LANUV model project and further sources.

3.1. Measures

The question arises whether single measures and the consistent integration of sustainability aspects into the different action fields or a systematic management might achieve the desired change. The LANUV started in 2014 to implement measures in some areas without an overlaying management system, due to the lack of resources. Especially in the field of energy savings, public administrations can gain a direct profit by reducing energy costs [20], and indirectly, for example, in a sense of positive effects for employee motivation. However, these co-benefits can also increase the willingness of implementation on work unit-level, releasing money, e.g., from energy saving measures, which could be used for other purposes, “provided that the (partial) budget responsibility lies with the same work units” [29] (p. 23). The instrument of the sustainability budget, with goals and key figures of the units being based on sustainability criteria and thus linked to the decisions on the budget, can support this process [26]. The implementation of specific activities can also be expedient and useful, as the successes at the federal level in the areas of “missionE” (40,000 employees reached since 2012) and the consideration of life-cycle costs in procurement (approx. 2/3 of all departments) clearly show [38]. Even though the measures taken in the LANUV proved to be a good starting point, a holistic perspective cannot arise and continuous improvement across all SDGs on the entire administrative level cannot be controlled. Thus, sustainability should be part of the corporate strategy [39] and this overarching strategy should be promoted, as it avoids single, independently controlled initiatives [40]. Furthermore, by focusing on single measures, a preference of easy, low-cost ones might be the result, neglecting costly and high-effort ones that would bear a significant sustainability impact [41,42]. This implies that a systematic management approach is required, both in a state authority and at the level of the entire state administration. This can help combine existing measures as well as foster permanent integration of sustainability aspects and continuous improvement driven by aims and indicators. The New Public Management, referring to the integration of management techniques from the private in the public sector, offers a good basis for environmental management systems focusing on such instruments [43]. Furthermore, it structurally avoids unfair “greenwashing” [44]. However, since both strategies might lead to a change in the processes and a greater consideration of sustainability aspects, they can be pursued in parallel, working towards an organizational anchoring and permanent cultural change [29].

Beside the question, whether it is a good decision to launch single measures by themselves or not, many measures have already been integrated in the legal framework and have resulted in obligations for the public administration. The social dimension is particularly covered well, since appointing commissioners for, e.g., inclusion or equality is mandatory and employees are either subject to collective agreements or they are civil servants, which offers security and certain rights. However, including these in the sustainability management offers a new perspective and helps improve the established processes beyond legal obligations. A development is essential to address current and upcoming challenges like, e.g., gender equality beyond only two sexes or the integration of people with migration background, which are addressed as key points in the federal sustainability strategy as well [1]. Indeed, there already are state laws prescribing integration [45], but key indicators are needed to evaluate the success and to implement concrete measures to improve the situation.

3.2. Resources

All of the mentioned examples in chapter two of measures in the fields of action and the crosscutting issue of climate neutrality show that additional financial and personnel resources have to be available for a professional implementation, especially with regard to complex measures. For the introduction of an environmental management according to EMAS, the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety recommends a person with a full-time job and no additional work to drive the introduction forward [46].

Overall, it should be taken into consideration that the issues corporate environmental and sustainability management as well as climate neutrality are usually not part of the mandatory statutory tasks of a state authority, and therefore no additional resources are available, rendering it impossible for many state authorities to improve their sustainability performance in a structured manner. One exception would be the financial sustainability, which is an important issue due to the often highly indebted public sector [20]. Here, performance indicators are deeply integrated in the processes [47], allowing for systematic improvement.

Even if single projects in other sustainability fields are considered as an opportunity for an in-depth discussion and continuous improvement, it always carries the risk of missing out on follow-up financing for certain measures and therewith on continuity [29]. In the case of the LANUV, the establishment of a structured management system would not have been possible without the acquisition of funding and external project-related allocations, respectively. In addition, staff responsible for, e.g., waste, energy, and procurement, face more documentation requirements and additional tasks especially in the phase of establishment. While introducing new standards might support sustainable development and save resources, for example when considering whole life cycle costs for procured goods [48], the integration of sustainability aspects like these into existing processes can only take place in the course of time. Bansal and DesJardine believe time to be the essence of sustainability being integrated on an operational level [41], which is apparently true for the public administration in particular.

3.3. Communication

It is extremely important to communicate success internally and externally [29]. Externally, it contributes to the LANUV NRW being politically perceived as role model other administrations might get inspiration and guidance from. Within the authority, it increases the identification with the topic. Hence, concrete implementation successes were made clear to all those involved at an early stage as suggested by Gelderman et al. [40]. This led to a positive impression and high acceptance at all levels of the organization, while increasing external perception at the same time [26]. Additionally, a study from the Netherlands revealed organizational sustainability to be positively related to overall job satisfaction [49].

Furthermore, the support of the top management of an organization is necessary for the successful establishment of a management system [16,50,51], not only by providing human and financial resources, but also by backing the entire process and the associated objectives. Once implemented, sustainability management benefits from good administrative leadership as it leads to overall improvement [52], including employee engagement and motivation [53] as well as personal development and a creativity-friendly environment [54]. Indeed, the top authority management must be regularly informed about the implementation status of the sustainability management and, on their part, spread the information in other state institutions as well as the public.

The LANUV established the basis for a change process in the entire organization by means of various sustainability projects. Since these changes are often associated with uncertainty about the future, employees might consider them as dangers and risks, even though they seek some kind of involvement regarding the process at the same time [55]. In order to address these issues, a wide range of participation options, such as employee forums, management conferences, and workshops were realized to onboard the staff and reach a high level of identification with the process. This is the ideal ground to benefit from the pro-environmental behavior within most of the workforce, which is referred to as “eco-initiative” [56]. The active participation in workshops and idea management shows the interest in bringing specialist knowledge and everyday experience into the process. Making use of knowledge that is already present is one key for improvement [57]. The participation also clarifies the expectation that the employees perceive a concrete and timely implementation of measures, desirable and expedient for continuous improvement, as particularly important. Altogether, the sustainability management in the LANUV creates an innovation-friendly atmosphere, increasing employee satisfaction and making the authority more attractive as an employer, especially for young people starting out in environmental and sustainability professions.

3.4. Skills

A successful sustainability management needs a skilled person in charge of the process. Therefore, a commissioner should be appointed for the entire phase of establishment, permanently controlling the formal processes of the management system and organizing the involvement of all employees and the active communication [51]. This person needs persuasiveness in order to permanently promote the interest in the topic of sustainability in the organization and to generate a spirit of optimism in the workforce, encouraging creative ideas. The person needs a direct link to and support of the top management in order to have a positive influence on the decision-making processes for the operational sustainability, as top management is the most influential actor [40]. By building up a task force for the operational sustainability management, other people and committees, such as the staff council, the equality opportunity officers, and a representative body for disabled employees take part into the process and take over tasks. Since the design of management elements is sometimes very complex and needs explaining, exchanges with experienced environmental officers and appropriate training courses are particularly helpful in that regard.

Additionally, staff responsible for procurement or canteen operations should be offered further education on sustainability issues (e.g. [48]). This will lead to a high skilled work force that is able to properly address the challenges of, e.g., green public procurement or sustainable food supply.

3.5. Management System

In order to achieve a verifiable contribution in the state administration to cope with future tasks in the areas of climate neutrality and sustainability as well as to meet the requirements of the state administration’s role model function, all public institutions should take measures to achieve a necessary organizational and structural change. However, public administrations are usually struggling to welcome new ideas or unconventional approaches [58]. In particular, the existing basic conditions and regulations of public administrations are often not conducive to such a change and sometimes even counterproductive, for example when favoring the low-cost options in business travel or procurement [29]. It is always a trade-off between goals and policies regarding costs, quality, environmental protection, and other aspects [59]. In addition to an annual program of measures, the management system should contain an indicator-based success control. All necessary processes are established by means of internal monitoring audits, a management review as well as an ongoing and transparent reporting to the public and regular external assessments. The LANUV meets these requirements either by already following nationally and internationally established sustainability and reporting standards (e.g., DIN ISO 14001, ISO 26000, EMAS) or by preparing to follow them in the near future (e.g., GRI, DNK). As there are many common elements and processes, the use of several established standards allows for a comprehensive framework, including an economical approach as well as a high degree of comparability of the used instruments and reports, transparency, and organized development [60]. At the same time, it supports the institutions’ credibility without and within, also contributing to, e.g., employees’ commitment and involvement [57]. Furthermore, Greco et al. emphasize the importance of a fixed and strong set of indicators in their study on Italian and Australian cities, because the absence of strict rules on reporting results in a lack of transparency and credibility [61]. Regarding the standards, a study on the interface between EMAS and DNK shows that the combination of both systems results in advantages and synergy effects [62].

In addition to that, clear responsibilities and structures are required in a state authority for the introduction and continuous further development of a sustainability management. This involves appointing a sustainability management commissioner as well as having supporting staff members to ensure the successful implementation of a management system. This only works if the sustainability team closely cooperates with the responsible unit for implementation or the specialist unit. The responsibility for the budget and the implementation of measures as well as the authority for processes usually do not lie with the sustainability team, but with other units, like, e.g., the department for IT service, the vehicle fleet, or the internal service. These units in turn have their own interests or are bound to guidelines, for example with regard to the owner of the property or the IT strategy of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. In that regard, Gelderman et al. state that budget owners are the most influential actors next to top management [40]. Hence, the sustainability team itself cannot implement many measures or restructure processes. This resulted in a particularly high level of effort in terms of coordinating all interests, bundling resources, and meeting the time schedule. Therefore, a sustainability management should aim to integrate sustainability aspects in existing processes and avoid establishing parallel structures. Fostering the connections within the organization is one sign of a sustainable organization [63].

Furthermore, regarding all activities in the field of building and property management, the LANUV is not able to act independently as a tenant, but relies on the property owner. This applies not only to the implementation of the measures, but also to the data collection for key figures and indicators. Depending on the structure and the range of issues, this can sometimes result in considerable friction losses for the sustainability management. Regular discussions with the proprietors can contribute to an improvement.

Finally, a connection of the sustainability management with the existing management systems, such as the quality management, significantly reduces the effort, as existing structures can be taken up. For example, internal audits can be organized in parallel, avoiding a double burden on employees due to the audits and strengthening the willingness to collaborate. Another example would the use of energy management as groundwork, on which the state administration of Baden-Wuerttemberg followed through. Since 2013, all state ministries and since 2016 some large authorities and institutions of the subordinated administrative level, have been certified according to the international energy management standard ISO 50001, whereupon as the next step an environmental management is built [64]. If extensive structures in the field of climate-neutral state administration already exist, e.g., being the case in state Hesse, Germany, synergy effects might be used as well. The identification of CO2 emissions in the process of reaching climate-neutral operation in 2030 as described by the Hessian Ministry of the Environment, Climate Protection, Agriculture and Consumer Protection [65] as well as an approach based on the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle reveal the links to EMAS.

Since the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has harmonized its management norms by means of the High Level Structure (HLC), an integrated management system can easily be built from several systems, e.g., by adding an environmental management system according to EMAS or ISO 14001 to the quality management.

4. Conclusions

The demand to integrate more sustainability and climate protection into official structures and actions exists at all political levels in Germany. The state government of North Rhine-Westphalia has specified important framework conditions for a sustainable and climate-neutral state administration. The LANUV as a model authority was chosen as an example to illustrate a way working towards these goals. In the following paragraphs, some major findings are summed up with respect to the great endeavor of spreading sustainability and climate-neutrality in the public administration.

In both developing and testing management processes, the LANUV kept a high level of transparency. The sustainability management of the state office benefits considerably from the high affinity and the outstanding specialist knowledge in the workforce, resulting in enhanced acceptance. Many other public administrations do not have the same basis and hence may have to orientate more closely to less motivated employees concerning questions of sustainability. Therefore, transferability is only possible to a limited extent. However, the findings give some idea about possible strategies establishing a sustainability management within a public administration and give hints for conducive general framework conditions:

The implementation of measures should ensure a long-term perspective relying on key indicators and performance monitoring, preferably being integrated in structured management systems. However, especially institutions without intrinsic motivation and strong troubleshooters might be introduced to the topic by means of single measures. This approach seems to make sense, as management systems are complex and the coherencies are often considered to be in need of explanation and difficult to communicate, making advice and a superior coordination partly indispensable. Furthermore, it is only possible to achieve a successful implementation if additional financial and personnel resources are made available and the expenditure burden follows the task burden.

Addressing general framework conditions, a systematic, sustainability-oriented administrative program is indeed required, but just a few state authorities will introduce or can adequately introduce a climate and sustainability management on a voluntary basis due to the obstacles outlined before. On the other hand, intrinsically motivated administrations can foster the rollout and achieve quick success [29]. However, even these administrations need to ensure transparency towards the public and foster the participation of employees, as they are both a requirement and an equally important success factor of sustainability management in the state administration.

Accordingly, a mandatory decision is needed at the state level and should be accompanied by the obligation to appoint management representatives for operational sustainability and climate neutrality in all institutions of the administration [29]. The Wuppertal Institute suggests “the establishment of an organizational unit, whose task is to provide nation-wide support and also to promote the implementation of sustainability management systems” [29] (p. 45).

To support a nationwide management process, an advanced training and communication program would be required. Climate protection and sustainability obviously still need more time and expertise in the public administration to be accepted as an obligation. Not until then will the necessary resources provided for established processes such as workplace health management or equality be made available.

Already existing management systems in the state administration, such as environmental, quality, or energy management, offer the possibility of using existing and comparable structures and thus significantly reduce the effort required to implement climate and sustainability management. Regarding the social dimension, even though a good legal groundwork has been established, further efforts should be made to integrate associated elements into a management system in the future. The more recent social development makes it necessary, for example, to work towards gender equality, to employ more people with a migration background, to promote part-time workers, and to integrate handicapped people, especially with regard to reaching management positions.

The LANUV continuously passes on its experience to other public institutions. In this context, the activities are extensively communicated in digital formats as well as blueprints, and best practice examples are made available to other institutions within the state administration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B., G.O. and M.D.; formal analysis, F.B. and M.D.; investigation, F.B., G.O. and M.D.; resources, G.O.; data curation, F.B. and M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, F.B., G.O., and M.D.; writing—review and editing, F.B. and M.D.; visualization, F.B.; supervision, G.O.; project administration, F.B.; funding acquisition, F.B. and G.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The development of an ecological and sustainability management as well as several accompanying measures were funded by the following institutions: German Federal Environmental Foundation (DBU); Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure (BMVI); Ministry for Environment, Agriculture, Conservation and Consumer Protection of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia (MULNV); Ministry of Economic Affairs, Innovation, Digitalization and Energy of the State North Rhine-Westphalia (MWIDE).

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their critical comments and suggestions. This helped broaden the horizon while at the same time being more concise with regard to the core content, hence improving this piece of work tremendously.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Federal Government of Germany. Deutsche Nachhaltigkeitsstrategie—Weiterentwicklung; Federal Government of Germany: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Riedel, H. Nachhaltige Entwicklung des öffentlichen Sektors—Mit dem Reformkompass auf Kurs bleiben! Arb. Wirtsch. Verwalt. Inf. 2013, 59, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- State Government of North Rhine-Westphalia. Climate Protection Law of North Rhine-Westphalia—29.01.2013, 4th ed.; Gesetz–und Verordnungsblatt: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry for Economic Affairs, Innovation, Digitalization and Energy of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia (MWIDE). Klimaschutz in Nordrhein-Westfalen—Entwicklung der Treibhausgas-Emissionen, Ziele und Strategien, Instrumente und Perspektiven; MWIDE: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Auf dem Weg zur Klimaneutralen Bundesverwaltung 2030, Pressemitteilung Nr. 175/20. Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU). Available online: https://www.bmu.de/pressemitteilung/auf-dem-weg-zur-klimaneutralen-bundesverwaltung-2030/ (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Gherardi, L.; Linsalata, A.M.; Gagliardo, E.D.; Orelli, R.L. Accountability and Reporting for Sustainability and Public Value: Challenges in the Public Sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösler, C. Lokale Agenda 21 in deutschen Städten. In Lokale Agenda 21 Prozesse –Erklärungsansätze, Konzepte, Ergebnisse, Reihe „Städte und Regionen in Europa“ Band 7; Mühlich, H., Mühlich, E., Eds.; Springer: Opladen, Germany, 2000; pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkeley, H.; Betsill, M. Re-thinking Sustainable Cities: Multilevel Governance and the „Urban Politics“ of Climate Change. Environ. Politics 2005, 14, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Kern, K. Local Government and the Governing of Climate Change in Germany and the UK. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 2237–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, F.; Kamlage, J.-H. Kommunaler Klimaschutz—Handlungsmöglichkeiten und Rahmenbedingungen in deutschen Städten und Gemeinden. KWI Work. Paper. 2015. 2/2015. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-68793-2 (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Roman, A.V. Institutionalizing sustainability: A structural equation model of sustainable procurement in US public agencies. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 1048–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, I.; Domingues, A.R.; Caeiro, S.; Painho, M.; Antunes, P.; Santos, R.; Videira, N.; Walker, R.M.; Huisingh, D. Sustainability policies and practices in public sector organisations: The case of the Portuguese Central Public Administration. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, M.; Vallés, J. An analysis of the implementation of an environmental management system in a local public administration. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 82, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeemering, E.S. Sustainability management, strategy and reform in local government. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankele, K.; Kottmann, H. Ökologische Zielfindung im Rahmen des Umweltmanagements. Schriftenreihe des IÖW 147/00; IÖW: Berlin, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, S. Sustainability Management. In Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility; Idowu, S.O., Capaldi, N., Zu, L., Gupta, A.D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.M.; Scavarda, A.; Hofmeister, L.F.; Thomé, A.M.T.; Vaccaro, G.L.R. An analysis of the interplay between organizational sustainability, knowledge management, and open innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorino, D.J. Sustainability as a Conceptual Focus for Public Administration. Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opp, S.M.; Saunders, K.L. Pillar Talk: Local Sustainability Initiatives and Policies in the United States—Finding Evidence of the “Three E’s”: Economic Development, Environmental Protection, and Social Equity. Urban Aff. Rev. 2013, 49, 678–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, R. Nachhaltigkeit in der Verwaltung—Wunschdenken oder Realität? Jahrb. Schweiz. Verwalt. 2014, 5, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarini, A.; Opoku, A.; Vagnoni, E. Public healthcare practices and criteria for a sustainable procurement: A comparative study between UK and Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Ionescu, L.; Uță, C.; Hurloiu, I.; Andronie, M.; Dijmărescu, I. Environmentally Responsible Behavior and Sustainability Policy Adoption in Green Public Procurement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachhaltigkeit und Klimaneutralität. Federal Academy for Public Administration (BAköV). Available online: https://www.bakoev.bund.de/DE/02_Themen/Nachhaltigkeit_Klimaneutralit%C3%A4t/Nachhaltigkeit_Klimaneutralitaet.html?nn=b65de583-1521-4a5d-8640-d3ad399d6e90#doc02903dbf-284f-45df-a288-9822c12dd86dbodyText2 (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- ÖKOPROFIT® in Nordrhein-Westfalen—Umwelt und Wirtschaft Gemeinsam Stärken. Ministry for Environment, Agriculture, Conservation and Consumer Protection of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia (MULNV). Available online: https://www.umwelt.nrw.de/umwelt/umwelt-und-ressourcenschutz/ressourceneffizientes-wirtschaften/oekoprofit/ (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2009 on the Voluntary Participation by Organisations in a Community Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS), Repealing Regulation (EC) No 761/2001 and Commission Decisions 2001/681/EC and 2006/193/. Official Journal of the European Union, L342/1. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2009/1221/oj (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Heinrichs, H.; Schuster, F. Nachhaltige Verwaltung. In Handbuch zur Verwaltungsreform; Veit, S., Reichard, C., Wewer, G., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Environment Agency (UBA). Klimamanagement in Unternehmen; UBA: Dessau, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- German Environment Agency (UBA). Auf dem Weg zum Treibhausgasneutralen UBA—Aktualisierte Umwelterklärung des Umweltbundesamtes; UBA: Dessau, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schostok, D.; Prantner, M.; Nagel, F.; Ossadnik, I. Nachhaltige Landesverwaltung NRW. Bericht zum Forschungsmodul FM B3 im Forschungsprojekt „Umsetzungserfahrungen mit Landesnachhaltigkeitsstrategien—Fallstudie Landesnachhaltigkeitsstrategie NRW“; Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment, Energy: Wuppertal, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Die globalen Nachhaltigkeitsziele Konsequent Umsetzen—Weiterentwicklung der Strategie für ein Nachhaltiges Nordrhein-Westfalen. State Government of North Rhine-Westphalia. Available online: https://www.umwelt.nrw.de/fileadmin/redaktion/Broschueren/nrw_nachhaltigkeitsstrategie_2020.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Heinrichs, H.; Martens, P.; Michelsen, G.; Wiek, A. (Eds.) Sustainability Science; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wiek, A.; Lang, D.J. Transformational Sustainability Research Methodology. In Sustainability Science; Heinrichs, H., Martens, P., Michelsen, G., Wiek, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry for Climate Protection, Environment, Agriculture, Nature and Consumer Protection of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia (MKULNV). Klimaschutzplan Nordrhein-Westfalen—Klimaschutz und Klimafolgenanpassung; MKULNV: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Svara, J.H.; Watt, T.C.; Jang, H.S. How Are, U.S. Cities Doing Sustainability? Who Is Getting on the Sustainability Train, and Why? Cityscape J. Policy Dev. Res. 2013, 15, 9–44. [Google Scholar]

- Roberto, F.; Maglio, R.; Rey, A. Accountability and Sustainability Reporting in the Public Sector. Evidence from Italian Municipalities 2020. In CSR and Sustainability in the Public Sector; Crowther, D., Seifi, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, G.; Sciulli, N.; D’Onza, G. The Influence of Stakeholder Engagement on Sustainability Reporting: Evidence from Italian local councils. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 465–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaston, I. Public SECTOR Management: Mission Impossible? Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Government of Germany. Nachhaltigkeit Korrekt im Verwaltungshandeln Umsetzen—Maßnahmenprogramm Nachhaltigkeit, Monitoring Bericht 2019; Federal Government of Germany: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K.-H. Green supply chain management implications for “closing the loop”. Transp. Res. Part E 2008, 44, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelderman, C.J.; Semeijn, J.; Vluggen, R. Development of sustainability in public sector procurement. Public Money Manag. 2017, 37, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; DesJardine, M.R. Business Sustainability: It is about time. Strateg. Organ. 2014, 12, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torugsa, N.; Arundel, A. Complexity of Innovation in the Public Sector: A Workgroup-Level Analysis of Related Factors and Outcomes. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 18, 392–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojar-Fijalkowski, T. Directions of changes taking place in polish public administration. Право Государство 2017, 1–2, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- German Environment Agency (UBA). Leitfaden Treibhausgasneutralität in der Verwaltung; UBA: Dessau, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- State Government of North Rhine-Westphalia. Participation and Integration Law of North Rhine-Westphalia—14.02.2012. Gesetz Verordn. 2012, 5, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU). EMAS Leitfaden für Behörden. Umsetzungshilfe für die Einführung eines Umweltmanagementsystems nach EMAS in Behörden; BMU: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hezri, A.A.; Dovers, S.R. Sustainability indicators, policy and governance: Issues for ecological economics. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 60, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Andersson, G.; Gourlay, R.; Karner, S.; Mikkelsen, B.E.; Sonnino, R.; Barling, D. Balancing competing policy demands: The case of sustainable public sector food procurement. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crucke, S.; Kluijtmans, T.; Meyfroodt, K.; Desmidt, S. How does organizational sustainability foster public service motivation and job satisfaction? The mediating role of organizational support and societal impact potential. Public Manag. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusinko, C.A. Using Quality Management as a Bridge to Environmental Sustainability in Organizations. SAM Adv. Manag. J. 2005, 70, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zutshi, A.; Sohal, A.; Adams, C. Environmental management system adoption by government departments/agencies. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2008, 21, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazi, D.C.; Turrini, A.; Valotti, G. Public sector leadership: New perspectives for research and practice. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2013, 79, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugaddan, R.G.; Park, S.M. Quality of leadership and public service motivation: A social exchange perspective on employee engagement. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2017, 30, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wart, M. Public-Sector Leadership Theory: An Assessment. Public Adm. Rev. 2003, 63, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, T.; Helgø, T.I.T. From Change Management to Change Leadership: Embracing Chaotic Change in Public Service Organizations. J. Chang. Manag. 2008, 8, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stritch, J.M.; Christensen, R.K. Going Green in Public Organizations: Linking Organizational Commitment and Public Service Motives to Public Employees’ Workplace Eco-Initiatives. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2014, 46, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.M.; Elrehail, H.; Alatailatc, M.A.; Elçi, A. Knowledge management, decision-making style and organizational performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, M.; McMurray, A.; Muenjohn, N. Innovation and Leadership in Public Sector Organizations. J. Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thai, K.V. Public procurement re-examined. J. Public Procure 2001, 1, 9–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, W.; Koc, M. Development of a systematic framework for sustainability management of organizations. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1255–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, G.; Sciulli, N.; D’Onza, G. From Tuscany to Victoria: Some Determinants of Sustainability Reporting by Local Councils. Local Gov. Stud. 2012, 38, 681–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German EMAS Advisory Board (UGA). Eine Formel für Nachhaltigen Erfolg? Studie zur Schnittstelle zwischen EMAS und dem Deutschen Nachhaltigkeitskodex; UGA: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moldavanova, A.; Goerdel, H.T. Understanding the puzzle of organizational sustainability: Toward a conceptual framework of organizational social connectedness and sustainability. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of the Environment, Climate Protection and Energy Sector Baden-Wuerttemberg. Aktualisierte Umwelterklärung; Ministry of the Environment: Stuttgart, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Unser Ziel: Eine CO2-Neutral Arbeitende Landesverwaltung bis 2030. Available online: https://co2.hessen-nachhaltig.de/de/ueber-uns.html (accessed on 4 January 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |