Resilient Rural Areas and Tourism Development Paths: A Comparison of Case Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The New Multi-Scalar Approach of the National Strategy for Inner Areas in Italy

3. The Monti Dauni As SNAI Pilot Area: Overview

4. Experiential Tourism as a Form of Resilience

4.1. Castelluccio Valmaggiore and the Project “Comunità del Cibo Buono e Autentico”

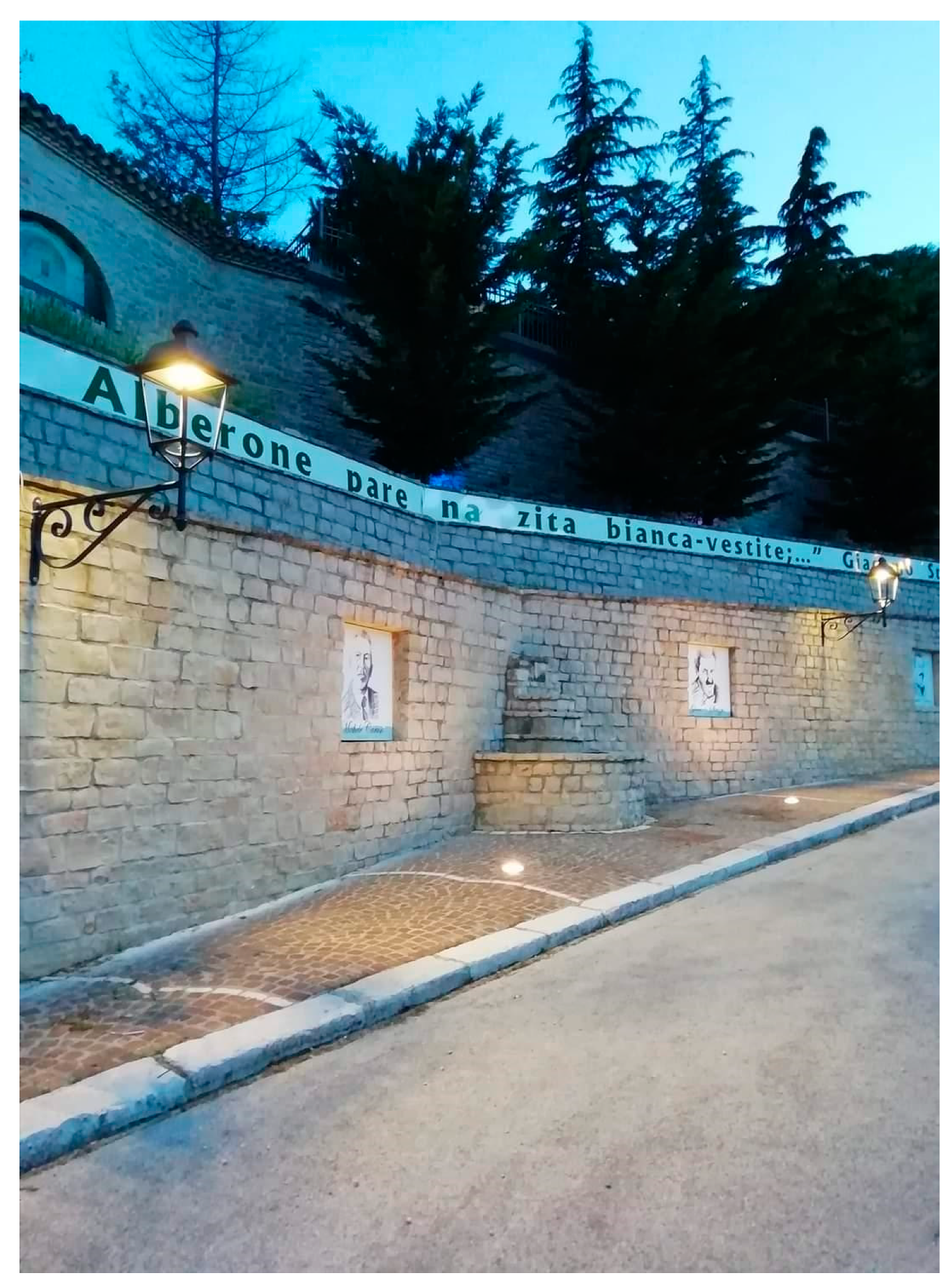

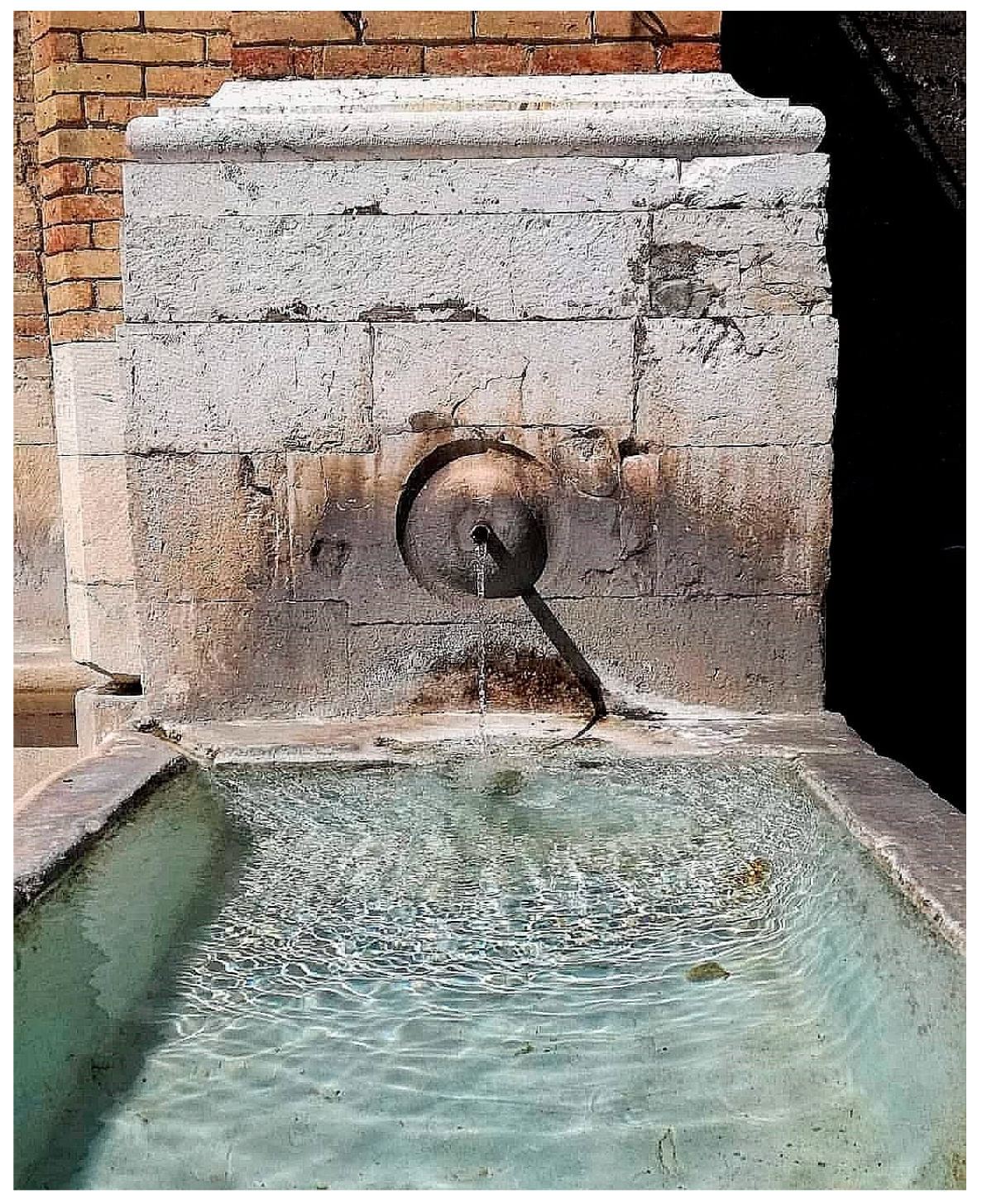

4.2. “Alberone pare Na Zita Bianca-Vestite...” (“Alberona Looks Like a Bride all Dressed in White”)

4.3. Biccari: When “Being a Community” Creates “Cooperation”

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pezzi, M.G.; Urso, G. Peripheral areas: Conceptualizations and policies. Introduction and editorial note. Ital. J. Plan. Pract. 2016, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Agenzia per la Coesione Territoriale. Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne: Definizione, Obiettivi, Strumenti e Governance. 2013. Available online: https://www.programazioneeconomica.gov.it (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Ugolini, G.M. Il rilancio delle aree rurali marginali: Anche una questione di progetto culturale. In Risorse Culturali e Sviluppo Locale; Madau, C., Ed.; Società Geografica Italiana: Rome, Italy, 2004; pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ciaschi, A.; De Iulio, R. Aree Marginali e Modelli Geografici di Sviluppo. Teorie e Esperienze a Confronto; Editore Sette Città: Viterbo, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sommella, R. Un gruppo di lavoro sulle vie interne allo sviluppo del Mezzogiorno. Geotema 1998, 10, 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cencini, C.; Dematteis, G.; Menegatti, B. L’Italia Emergente. Indagine Geo-Demografica sullo Sviluppo Periferico; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Coppola, P. L’osso e i suoi quesiti. Geotema 1998, 10, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Società Geografica Italiana. Politiche per il Territorio (Guardando all’Europa). Rapporto Annuale 2013; Società Geografica Italiana: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Celant, A. (Ed.) Ecosostenibilità e Risorse Competitive. Le Compatibilità Ambientali nei Processi Produttivi; Società Geografica Italiana: Rome, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Manzi, E. Centri minori tra geografia, urbanistica, beni culturali e ambiente. Spunti per una ricerca e un dibattito. Rivista Geografica Italiana 2000, 2, 255–272. [Google Scholar]

- Antolini, F.; Billi, A. Politiche di Sviluppo nelle Aree Urbane; UTET: Turin, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dipartimento Politiche Europee—Presidenza del Consiglio. Documento di Economia e Finanza. 2006. Available online: https://rgs.mef.gov.it (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Legge no. 147/2013, G.U. 27/12/2013. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2013/12/27/13G00191/sg (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Legge no. 158/2017, G.U. 02/11/2017. Available online: https://www.bosettiegatti.eu/info/norme/statali/2017_0158_piccoli_comuni.htm (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Turco, A. Configurazioni della Territorialità; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Space as Keyword. In David Harvey. A Critical Reader; Castree, N., Gregory, D., Eds.; Blackwell: Malden, UK, 2006; pp. 270–293. [Google Scholar]

- Dematteis, G. Regioni geografiche, articolazione territoriale degli interessi e regioni istituzionali. Stato Mercato 1989, 27, 445–467. [Google Scholar]

- Mannella, S. L’ambiente e l’agricoltura. In Scritti geografici sul Subappennino Dauno; Mannella, S., Fiori, M., Carparelli, S., Mininno, A., Varraso, I., Eds.; Pubblicazioni del Dipartimento di Scienze Geografiche e Merceologiche, Università degli Studi di Bari; Adriatica Editrice: Bari, Italy, 1990; pp. 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mannella, S.; Fiori, M.; Carparelli, S.; Mininno, A.; Varraso, I. Scritti geografici sul Subappennino Dauno; Pubblicazioni del Dipartimento di Scienze Geografiche e Merceologiche, Università degli Studi di Bari; Adriatica Editrice: Bari, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bissanti, A.A. La Dimora Rurale nel Tavoliere e nel Subappennino Dauno; Memorie Istituto di Geografia, Facoltà di Economia e Commercio, Università degli Studi di Bari, NS 3; Tipo Sud: Bari, Italy, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Bissanti, A.A. La Puglia. In I Paesaggi Umani; Touring Club Italiano (TCI): Milan, Italy, 1977; pp. 166–179. [Google Scholar]

- Bissanti, A.A. Puglia. Geografia Attiva; Adda: Bari, Italy, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rinella, A. Ripensare la realtà di un’area depressa: Il caso del Subappennino Dauno. Economia e Commercio 1990, 3, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Novembre, D. Puglia. Popolazione e Territorio; Milella: Lecce, Italy, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Amoruso, O. Progresso e regresso demografico nei comuni pugliesi: Una prima individuazione di ambiti spaziali. In L’Italia Emergente. Indagine Geo-Demografica sullo Sviluppo Periferico; Cencini, C., Dematteis, G., Menegatti, B., Eds.; Angeli: Milan, Italy, 1983; pp. 499–517. [Google Scholar]

- Varraso, I. L’esile copertura antropica della “montagna” pugliese. In Scritti Geografici sul Subappennino Dauno; Mannella, S., Fiori, M., Carparelli, S., Mininno, A., Varraso, I., Eds.; Pubblicazioni del Dipartimento di Scienze Geografiche e Merceologiche, Università degli Studi di Bari; Adriatica Editrice: Bari, Italy, 1990; pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel, C. Patrimoni paesistici, riforme amministrative e governo del territorio: Svolte e percorsi dissolutivi di rapporti problematici. Boll. Soc. Geogr. Ital. 1999, 4, 295–318. [Google Scholar]

- Banfield, E.C. Le Basi Morali di una Società Arretrata; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- GAL Meridaunia. Strategie di Sviluppo Locale “Monti Dauni”. Programmazione 2014–2020. 2014, p. 76. Available online: http://www.meridaunia.it/upload/PAL_GAL_MERIDAUNIA%202014-2020.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- GAL Meridaunia. Monti Dauni. La Puglia da Scoprire. 2015, p. 180. Available online: http://www.meridaunia.it/upload/upl1/Guida%20GAL%20Meridaunia%20-%20WEB.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Regione Puglia. Piano Paesaggistico Territoriale Regionale; (Scientific Director: A. Magnaghi), Document no.5 Ambito 2/Monti Dauni, February 2015. Available online: http://www.paesaggiopuglia.it (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Legge no. 64/1986, G.U. 14/03/1986. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:legge:1986-03-01;64 (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Decandia, L. Ripensare la “società dell’azione”, e ricominciare a “guardare il cielo”: La montagna come “controambiente” del sublime in una inedita partitura urbana. Scienze del Territorio 2016, 4, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Associazione Borghi Autentici d’Italia. Available online: www.borghiautenticiditalia.it (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Associazione I Borghi Più Belli d’Italia. Available online: www.borghipiubelliditalia.it (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Decision n. 870 of April 2015. Available online: http://burp.regione.puglia.it/en/bollettino-ufficiale?p_p_id=burpsearch_WAR_GestioneBurpportlet&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&p_p_col_id=column-1&p_p_col_count=1&_burpsearch_WAR_GestioneBurpportlet_jspPage=%2Fhtml%2Fburpsearch%2Fview.jsp&_burpsearch_WAR_GestioneBurpportlet_opz=dettagliosezione&_burpsearch_WAR_GestioneBurpportlet_anno=2015&_burpsearch_WAR_GestioneBurpportlet_burpId=15781&_burpsearch_WAR_GestioneBurpportlet_sezioneId=4574633&_burpsearch_WAR_GestioneBurpportlet_delta=75&_burpsearch_WAR_GestioneBurpportlet_keywords=&_burpsearch_WAR_GestioneBurpportlet_advancedSearch=false&_burpsearch_WAR_GestioneBurpportlet_andOperator=true&_burpsearch_WAR_GestioneBurpportlet_resetCur=false&_burpsearch_WAR_GestioneBurpportlet_cur= (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Regione Puglia. Deliberazione della Giunta Regionale n. 951 5/6/2018. Available online: https://www.burp.regione.puglia.it (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Woodward, K.; Jones, J.P., III; Marston, S.A. Of eagles and flies: Orientations toward the site. Area 2010, 42, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. For Space; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- MiBACT (Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali e per il Turismo). Piano Strategico di Sviluppo del Turismo 2017–2022. 2016, p. 112. Available online: http://www.turismo.beniculturali.it (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- MacCannell, D. Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Setting. Am. J. Soc. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist: A Theory of the Leisure Class; Schocken: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Martinego, M.C.; Giaccaria, P. Autenticità e radicamento nel turismo esperienziale. Introduzione. In (S)radicamenti; Dansero, E., Lucia, M.G., Rossi, U., Toldo, A., Eds.; Società di Studi Geografici, Memorie Geografiche: Firenze, Italy, 2017; pp. 513–514. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, S. Modelli Gestionali per il Turismo come Esperienza. Emozioni e Polisensorialità nel Marketing delle Imprese Turistiche; Cedam: Padua, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A.; Goetz, M. Creare Offerte Turistiche Vincenti con Tourist Experience Design; Hoepli: Milan, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti, A. Beni comuni, patrimonio culturale e turismo. Introduzione. In Commons/Comusne; Società di Studi Geografici, Memorie Geografiche: Firenze, Italy, 2016; pp. 437–438. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbiosi, C. Turismo esperienziale e narrazione selettiva dei luoghi: Il ruolo delle comunità residenti. In (S)radicamenti; Dansero, E., Lucia, M.G., Rossi, U., Toldo, A., Eds.; Società di Studi Geografici, Memorie Geografiche: Firenze, Italy, 2017; pp. 521–527. [Google Scholar]

- Rinella, A.; Rinella, F. Dalle tessere marginali al mosaico progettuale in rete: Le proposte di sviluppo locale dell’associazione ‘Borghi Autentici d’Italia’. In Ripartire dal Territorio. I Limiti e le Potenzialità di una Pianificazione dal Dasso, Atti del X Incontro Italo-Francese di Geografia Sociale (Lecce, 30-31 March 2017); Pollice, F., Urso, G., Epifani, F., Eds.; Placetelling® Collana di Studi Geografici sui Luoghi e sulle Loro Rappresentazioni, Università del Salento: Lecce, Italy, 2019; pp. 211–223. ISBN 978-88-8305-145-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rinella, A.; Rinella, F. Verso una narrazione creativa e originale della montagna: Il Sistema delle Comunità Ospitali dei Monti Dauni. Boll. Soc. Geogr. 2018, 14, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Garibaldi, R. Viaggio per cibo e Vino. Esperienze Creative a Confronto; Aracne: Rome, Italy, 2017; Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- Finocchi, F. Geografie del Gusto; Aracne: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rinella, F. Processi di autenticazione e turismo dei “sapori” e dei “profumi”: Il progetto “Comunità del cibo buono e autentico. In Mosaico/Mosaic; Cerutti, S., Tadini, M., Eds.; Giornata di studio della Società di Studi Geografici: Novara, Italy, 2019; pp. 749–758. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E.; Cohen, S.A. Authentication: Hot and Cool. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 3, 1295–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandiera Arancione. Available online: https://www.bandierearancioni.it (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Club per l’UNESCO di Alberona. Available online: https://alberonaclubunesco.it (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Available online: https://amp.foggiatoday.it/eventi/festival-dieta-mediterranea-troia-lucera-alberona.html (accessed on 23 November 2020).

- Verses by M. Caruso in the Original Project of the “Muro della Poesia”. Available online: https://lucerabynigh.it/18201-Alberona-e-il-muraglione-dei-poeti (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Verses by G. Strizzi on the “Muro della Poesia”. Available online: http://alberona.blogspot.com/2010/09/alberona-una-sposa-di-bianco-vestita.html (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Comune di Alberona. Available online: https://www.comune.alberona.fg.it (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Alberona a 5 Stelle. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/alberona-a-5-stelle-226034901094416 (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Mayor of Alberona’s Facebook Profile. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/de.m.leonardo (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- AlberonaComunica. Available online: https://www.alberonacomunica.wordpress.com (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, P.A.; Sforzi, J. (Eds.) Imprese di Comunità. Innovazione Istituzionale, Partecipazione e Sviluppo Locale; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Legacoop. Cooperative di Comunità. Opportunità di Sviluppo e Lavoro per il Bene Comune. 2011. Available online: www.legacoop.coop/cooperativa-di-comunità (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Bandini, F.; Medei, R.; Travaglini, C. Territorio e persone come risorse: Le cooperative di comunità. Impresa Soc. 2015, 5, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Magnaghi, A. Il Progetto Locale. Verso la Coscienza di Luogo; Bollati Boringhieri: Milan, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Regione Puglia. Disciplina delle cooperative di comunità (L.R. n. 23 del 20.5.2014). Bollettino Ufficiale della Regione Puglia 2014, 66, 17.869–17.870. Available online: www.regionepuglia.it/bollettino-ufficiale (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Governa, F. Il Milieu Urbano. L’Identità Territoriale nei Processi di Sviluppo; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pollice, F. Alberghi di comunità: Un modello di empowerment territoriale. Territ. Cult. 2016, 25, 82–95. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperativa di Comunità di Biccari. Available online: https://www.coopbiccari.it (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Visit Biccari. Available online: htpps://www.visitbiccari.com (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Claval, P. Introduzione alla Geografia Regionale; Zanichelli: Milan, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Teti, V. Pietre di Pane. Un’Antologia del Restare; Quodlibet Studio: Macerata, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Teti, V. Quel Che Resta. L’Italia dei Paesi, Tra Abbandoni e Ritorni; Donzelli editore: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Reynaud, A. Disuguaglianze Regionali e Giustizia Socio-Spaziale; Unicopli: Milan, Italy, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Amadore, N. Strategia Nazionale Aree Interne, il Governo Spinge per Accelerare. Available online: https://www.ilsole24ore.com (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Martinelli, L. L’Italia è bella Dentro. Storie di Resilienza, Innovazione e Ritorno nelle Aree Interne; Altreconomia: Milan, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Raffestin, C. Territorialità, territorio, paesaggio. In Territorialità: Concetti, Narrazioni, Pratiche. Saggi per Angelo Turco; Arbore, C., Maggioli, M., Eds.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2015; pp. 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J. La Teoria Dello Sviluppo Economico; UTET: Turin, Italy, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Pileri, P.; Granata, E. Amor loci. In Suolo, Ambiente, Cultura Civile; Libreria Cortina: Milan, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Caravaggi, L.; Imbroglini, C. La Montagna Resiliente. Sci. Territ. 2016, 4, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MUNICIPALITIES | pop. | pop. | inh./sq. km. | inh./sq. km. | (IV–III)/III | % > 75 years old | % > 75 years old | ||

| m a.s.l. | sq. km. | 1991 | 2019 | 1991 | 2019 | % | 1991 | 2019 | |

| Accadia | 650 | 30.48 | 3107 | 2277 | 101.94 | 74.70 | −26.71 | 10.7 | 13.2 |

| Alberona | 732 | 49.25 | 1269 | 902 | 25.77 | 18.31 | −28.92 | 11.6 | 18.6 |

| Anzano di Puglia | 760 | 11.12 | 2365 | 1185 | 212.68 | 106.56 | −49.89 | 7.4 | 14.8 |

| Ascoli Satriano | 393 | 334.57 | 6892 | 6102 | 20.60 | 18.24 | −11.46 | 6.6 | 10.6 |

| Biccari | 450 | 106.31 | 3462 | 2696 | 32.57 | 25.36 | −22.13 | 7.9 | 16.8 |

| Bovino | 620 | 84.16 | 4546 | 3138 | 54.02 | 37.29 | −30.97 | 10 | 16.9 |

| Candela | 474 | 96.14 | 2809 | 2732 | 29.22 | 28.42 | −2.74 | 8.3 | 10.6 |

| Carlantino | 558 | 34.17 | 1449 | 916 | 42.41 | 26.81 | −36.78 | 6.8 | 16.1 |

| Casalnuovo Monterotaro | 432 | 48.17 | 2370 | 1434 | 49.20 | 29.77 | −39.49 | 12.1 | 16.8 |

| Casalvecchio di Puglia | 465 | 31.70 | 2410 | 1763 | 76.03 | 55.62 | −26.85 | 6.8 | 14.3 |

| Castelluccio dei Sauri | 284 | 51.31 | 1900 | 2097 | 37.03 | 40.87 | 10.37 | 7.4 | 10.3 |

| Castelluccio Valmaggiore | 630 | 26.66 | 1552 | 1253 | 58.21 | 47.00 | −19.27 | 10.1 | 18.4 |

| Castelnuovo della Daunia | 543 | 60.99 | 1991 | 1359 | 32.64 | 22.28 | −31.74 | 9.6 | 15.9 |

| Celenza Valfortore | 480 | 66.48 | 2299 | 1485 | 34.58 | 22.34 | −35.41 | 10.7 | 28.2 |

| Celle di San Vito | 726 | 18.21 | 297 | 164 | 16.31 | 9.01 | −44.78 | 14.1 | 21.3 |

| Deliceto | 575 | 75.63 | 4304 | 3671 | 56.91 | 48.54 | −14.71 | 9.8 | 12.5 |

| Faeto | 820 | 26.16 | 1010 | 614 | 38.61 | 23.47 | −39.21 | 13.6 | 11.1 |

| Monteleone di Puglia | 842 | 36.04 | 1608 | 977 | 44.62 | 27.11 | −39.24 | 13.2 | 12.3 |

| Motta Montecorvino | 662 | 19.7 | 1159 | 682 | 58.83 | 34.62 | −41.16 | 13.5 | 23.6 |

| Orsara di Puglia | 635 | 82.24 | 3530 | 2604 | 42.92 | 31.66 | −26.23 | 9.9 | 17.6 |

| Panni | 801 | 32.59 | 1083 | 740 | 33.23 | 22.71 | −31.67 | 15.8 | 21.6 |

| Pietramontecorvino | 456 | 71.17 | 3111 | 2612 | 43.71 | 36.70 | −16.04 | 10.1 | 14.7 |

| Rocchetta Sant’Antonio | 633 | 71.9 | 2293 | 1767 | 31.89 | 24.58 | −22.94 | 9.5 | 15.5 |

| Roseto Valfortore | 658 | 49.61 | 1513 | 1054 | 30.50 | 21.25 | −30.34 | 18 | 17.7 |

| San Marco la Catola | 683 | 28.4 | 1794 | 925 | 63.17 | 32.57 | −48.44 | 9.6 | 17.8 |

| Sant’Agata di Puglia | 794 | 115.79 | 3049 | 1886 | 26.33 | 16.29 | −38.14 | 12.9 | 15.2 |

| Troia | 439 | 167.22 | 7898 | 6985 | 47.23 | 41.77 | −11.56 | 6.8 | 12.7 |

| Volturara Appula | 526 | 51.87 | 744 | 397 | 14.34 | 7.65 | −46.64 | 18 | 23.8 |

| Volturino | 735 | 58.02 | 2224 | 1654 | 38.33 | 28.51 | −25.63 | 9.1 | 27.2 |

| TOTAL | 1936.06 | 74,038 | 56,071 | 38.24 | 28.96 | −24.27 | 9.6 | 14.4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ivona, A.; Rinella, A.; Rinella, F.; Epifani, F.; Nocco, S. Resilient Rural Areas and Tourism Development Paths: A Comparison of Case Studies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063022

Ivona A, Rinella A, Rinella F, Epifani F, Nocco S. Resilient Rural Areas and Tourism Development Paths: A Comparison of Case Studies. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063022

Chicago/Turabian StyleIvona, Antonietta, Antonella Rinella, Francesca Rinella, Federica Epifani, and Sara Nocco. 2021. "Resilient Rural Areas and Tourism Development Paths: A Comparison of Case Studies" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063022

APA StyleIvona, A., Rinella, A., Rinella, F., Epifani, F., & Nocco, S. (2021). Resilient Rural Areas and Tourism Development Paths: A Comparison of Case Studies. Sustainability, 13(6), 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063022