Abstract

As disasters become progressively more frequent and complex, better collaboration through partnerships with private business becomes more important. This research aimed to understand how platforms support the engagement of the private sector—especially logistics businesses—in humanitarian relief operations. The study was based on a literature review and on an investigation of an emblematic case of the cross-sector platform, recognized at a global level in logistics and supply chain management, between the United Nations World Food Programme and the Logistics Emergency Teams (WFP/LET), composed of four global leading logistics providers. The insights resulting from this paper may be of particular interest to both academics and professionals regarding the two sectors, profit and non-profit. This is because the implementation of the platform reflects the concrete benefit for people in need reached by the humanitarian relief operations. It may also constitute a useful tool for building an agile supply chain capable of being resilient in responding to sudden and unexpected changes in the context, both in humanitarian and commercial supply chains.

1. Introduction

The last decade has seen a dramatic upward trend in the magnitude, number, and impact of natural and human-made disasters around the world; in particular, every year, there has been an increase in natural disasters, claiming tens of thousands of lives, affecting several million people and causing extremely high economic damage, as recorded by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters [1,2].

In particular, in South Asia, the 2004 earthquake and the resulting tsunami caused approximately 230,000 victims and 1.7 million displaced persons; more than 40 countries and 700 non-governmental organizations (NGOs) offered humanitarian assistance, and from all around the world, donations higher than USD 13 billion arrived, thus “initiating the largest relief effort in history” [1] (p. 114). The “response of the private sector was unprecedented” [2] (p. 5), and the role of logistics service providers (e.g., UPS, FedEx, and DHL) was especially crucial: they provided free or subsidized transportation and logistics—together with their aid agency partners [2].

Before 2004, response was unbudgeted, and cross-sector collaboration “seemed unfeasible” [3,4] (p. 220). Traditionally, business has considered the social sector as “a dumping ground for spare cash, obsolete equipment, and tired executives” [5] (p. 123); from the perspective of the humanitarian sector, profit-driven companies have been seen “to be the cause of, rather than solution to, problems affecting the developing world” [4] (p. 220), e.g., environmental disasters, pollution, and intensive monocultures.

The 2004 tsunami represents a turning point in the engagement of the private sector in humanitarian operations [1,2]. After that, in fact, the private sector and the humanitarian sector have been exploring solutions for a more fruitful cooperation. With this disaster, the donation of non-monetary offers—of in-kind goods, information and communications technology (ICT) equipment, and logistics supports—was substantial; this has also revealed significant criticalities that deserve attention [1]: a complete list or schedule of what was needed and by whom was not available for the various companies; clear information about what useful materials companies had and where was not available; there was no specialized personnel who could support in the evaluation phases of the goods received during the ongoing operations in order to decide whether to accept them or not and how to manage them; too many unsolicited and even inappropriate items had arrived that took up space in airports and warehouses, and they were not used and remained unclaimed for months, occupying spaces that could accommodate more useful items; there was a scarcity of fuel for scheduled flights due to the arrival of unsolicited supplies; and many companies had not received acknowledgement for the help given [1].

Despite these criticalities, a number of companies were able to provide concrete support to humanitarian organizations in relief operations: these companies, unlike others, were able to help effectively and efficiently because they had already established relationships with the humanitarian sector before the tsunami occurred [2].

However, since the 2004 tsunami, companies and aid organisations have been evaluating the ways in which they could collaborate most fruitfully with one another [1]. The involvement of private sector companies has grown considerably in humanitarian action in recent years, especially in relief operations. In fact, “as disasters become increasingly complex, better collaboration not only with government agencies, military units, humanitarian organizations but also in partnerships with private business becomes ever more important” [6] (p. 487).

After 2004, in summary, at least two imperatives have emerged in academic and professional contexts:

- Coordination in the effort for humanitarian action, characterized by a very complex setting, which involves very different actors, both in terms of their culture, purposes, interests, and mandates and in terms of logistic skills and competences [7];

- Logistics in humanitarian action, as it makes the difference between successful or failed results in the humanitarian operation, and because it represents the most costly part of any disaster relief, accounting for about 70/80% of the total costs in each disaster operation [6,8].

These two imperatives lead to the consciousness of the need of a new approach supporting effective private sector–humanitarian engagement meeting the challenge of preparing for/responding to disasters, valorising the tool of the “platform” for the logistics coordination of the supply network.

There are very few studies from this specific perspective, although its study can be extremely useful as an example and source of learning for those actors and supply chains, both in the humanitarian and commercial sectors, which more in general are facing crisis events of different types, both critical unexpected shocks and also smaller discontinuities.

In view of these considerations, our research aimed to answer the following key research question.

RQ. How can platforms support in engaging the private sector—especially logistics businesses—in humanitarian relief operations?

To address this point, this paper was organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the theoretical background arising from the literature. The research methodology is described in Section 3, after which the case study is analysed in Section 4. The main results are discussed in Section 5, and in Section 6 conclusions are drawn and future research steps are proposed.

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Emerging Need for a New Approach in Cross-Sector Humanitarian Action: The Platform

Platforms in humanitarian action have the potential to facilitate effective private sector engagement [9]. They can be considered “intermediary mechanisms” or “multi-faceted” entities useful to promote and support the engagement and organization of different actors in humanitarian action [9] (p. 8). The platform could assume the form of “a network, a strategic alliance, a coalition, an organisation, a set of principles or guidelines, a temporary coalition, a series of events or online fora,” aiming at promoting and supporting the concrete and efficient engagement [9] (p. 8). This solution could also be utilized for the private sector in contributing with its own effort in humanitarian operations.

The concept of a platform, in a humanitarian context or other, is based on the widely accepted idea that platforms represent a space/interface in which different actors, skills, abilities, resources, knowledge, objectives, or needs could be more easily finalized in a concrete interaction, which otherwise would be much more difficult to achieve. A platform may realize this by facilitating the matching of interests, by creating communication opportunities among different actors, by setting up standardized technological interfaces, and/or by building cross-functional teams [10]. According to this, three main platform characteristics emerge [10]: into the platform “framework” activities, resources and people may be better organized for the common objective; this framework is quite stable over time in terms of organizational structure, however, the activities, resources, and people that it comprises may be easily “reconfigurable.” The platform is an active support structure that facilitates “re-configurability” [11]. Re-configurability—together with modularity—facilitate the emergence of an “ecosystem” of complementary activities, resources, and people [12]. Modularity may enable the emergence of the ecosystem, allowing different interdependent organizations to coordinate without a formal hierarchy [13]. There are studies that suggest that “platform ecosystems” arise from positive feedbacks or “network effects” [10]. Going deep into the analysis by focusing on ecosystems (and on networks and systems), especially in service contexts, would enable practitioners to extend their (business or humanitarian) perspective to deal with increasingly complex business settings and co-create value in benefit of their stakeholders [14].

Platforms may support the engagement of the private sector in humanitarian action in all the activities that characterize the disaster management cycle [9]—as mitigation, preparedness, response, and reconstruction—and in development activities, related not only to disaster reliefs, but also to continuous aid work [2,6,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23].

The mitigation phase aims at reducing disaster risk and social vulnerability through the use of laws and mechanisms mainly related to the responsibilities of governments and institutions. The preparation phase aims at implementing a concrete successful operational response, during the period before a disaster strikes, through planning activities and strategies. The response phase aims at bringing help where needed as soon as possible; it refers to the various operations that are instantly implemented after a disaster occurs and has two sub-objectives [2]: to activate the immediate response of the “silent” or “temporary” network for the operation [24] and to restore as quickly as possible the essential conditions and services needed for the highest possible number of beneficiaries [2]. Coordination and collaboration among actors involved in the humanitarian action deserve special consideration in the response stage [7,15,16,25,26,27]. The reconstruction phase aims at rehabilitating normal conditions and rebuilding structures and infrastructures in the aftermath of a disaster, in the medium to long term [2].

Different platforms supporting the private sector’s engagement in humanitarian action have been studied by Oglesby and Burke in their research in 2012 [9]; the authors propose nine key findings emerging from the research, and not necessarily all findings are applicable to all the cases analysed in consideration of the great diversity (considering the geographic context, the scale, the purpose, and the activities) between the platforms included in the study. They are as follows [9] (pp. 4–5, pp. 21–30):

- “platforms emerge to address complex crisis challenges that individual organisations or partnerships are unable to overcome alone” [9] (p. 4, p. 21);

- “platforms reflect, and can contribute to, a changing concept and dynamic of humanitarian action with a great focus on disaster risk reduction and preparedness. However, they often struggle to turn this intention into practical action” [9] (p. 4, p. 23);

- “an added value of platforms is that they provide a clear access point for the private sector to engage in humanitarian action and to help overcome common challenges to engagement” [9] (p. 4, p. 24);

- “platforms struggle to define and measure their impact” [9] (p. 4, p. 25);

- “platforms across different contexts value common success characteristics which allow them to effectively serve their members” [9] (p. 5, p. 25);

- “currently there is no identifiable home or information repository for the learning platforms generate on how they facilitate the private sector’s engagement in humanitarian action” [9] (p. 5, p. 28);

- “platforms have a record of inconsistent progress in forging links with governments” [9] (p. 5, p. 28);

- “platforms recognise that they need to be adaptive, but face common challenges in doing this” [9] (p. 5, p. 29);

- “platforms recognise they will have to work in new ways to remain relevant in future contexts” [9] (p. 5, p. 29).

The study carried out by Oglesby and Burke (2012) helps in reflecting how much can be learnt by understanding platforms in terms of the possibility of making humanitarian and non-humanitarian actors working together [9].

The contribution of private companies in alleviating the economic impact of disasters, crises, and disruptions “makes good business sense” [1]. The intervention of companies, in collaboration with humanitarians, in disaster relief, seeks “to build on synergies between the business and humanitarian communities to advance humanitarian objectives and at the same time support Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)” [28] (p. 350). CSR is an area “where commercial and philanthropic intentions can easily overlap” also in a humanitarian context [27] (p. 140). Companies that intend to achieve their economic competitiveness objectives also by supporting responsible actions to improve society are motivated by the well consolidated assumption that economic and social value are not in opposition to each other, but rather overlap [29,30].

In a broader perspective, this engagement refers to the more comprehensive “sustainability” concept, which has become a business imperative and has also been recognised as a strategic goal by multiple organisations, also embracing a broadening perspective of the sustainability of “supply chains” or networks to which they belong [31,32,33]. This is especially in a context where competition is no more among single companies but among supply chains [34]; and where sustainability is primarily based on the three dimensions, termed “triple bottom line” [35,36] (Elkington 1998; 2018): economic, environment, and society. Therefore, this “sustainable supply chain management” (SSCM) means that organizations are held simultaneously responsible for the economic, social, and environmental performance of the supply chain to which they belong [37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. A sustainable supply chain is no longer considered “nice to have” but necessary [44] (p. 44). Moreover, “ultimately SSCM contributes to a holistic and long-term strategic perspective of a company and its supply chain, thereby going beyond formal accountability, environmental and social regulations as imposed by governments, and goes beyond perspectives regarding the Triple Bottom Line as a balancing act” [45] (p. 3, p. 6), surviving over time.

In the context of humanitarian action, the social dimension is prevalent, but it cannot remain alone to be effective: the economic dimension is needed to concretely enable the social dimension [2], and the topic of environmental sustainability in humanitarian logistics is growing in the humanitarian agenda, and in a way that is linked with the two other dimensions.

Logistics, in particular, plays an important role in the implementation of a sustainability strategy from a supply chain perspective, for many years now [46].

2.2. Logistics in Humanitarian Action: Towards a Sustainable Supply Chain Management

The 2004 tsunami provided evidence that the effectiveness of emergency aid response hinges on logistics activities and their speed and efficiency [47], thus increasing the awareness of the crucial role played by logistics and supply chain management in humanitarian relief operations [8].

The definition of ‘‘humanitarian logistics’’ considers the people, resources, knowledge, and activities involved in planning, implementing, and controlling an efficient and effective flow and storage of materials (with their corresponding information and financial flows), from the points of origin to the place where they are in need when a disaster occurs [6,48]. Moreover, it is crucial to efficiently and effectively coordinate inter-organizational performance, eliminate redundancy, and maximize synergy along the entire emergency supply chain relationships, from a supply chain management perspective [2].

In humanitarian relief operations, both logistics and supply chain management abilities are decisive: the ones related to logistics are more focused on moving something or someone from one point to another, and the ones related to supply chain management are more focused on the coordination of the relationships among actors performing the logistics operations [2].

Therefore, proper investment in logistics during disaster relief management provides a real opportunity to develop and implement the effective and efficient use of resources in humanitarian operations [49]. Moreover, a strategic use of resources allows humanitarian organizations to increase donor trust and long-term commitment by progressively sceptical donors [50]. Unlike in the past, today more humanitarian organizations are called upon to report the effective use of what they have received from donors and to communicate the impact of their actions in relief operations to demonstrate that they are really reaching those in need [6].

Since logistics and supply chain management competences are those most needed by the humanitarian sector in managing disaster relief, companies dealing with the business of logistics and supply chain management can be considered among the most useful in being able to contribute, because the company’s contributions with the greatest impact on the social sector use “core business skills” [5,6]. Companies with their core business in logistics and supply chain management are the so-called “logistics service providers”—LSPs: by virtue of their competences, they can play a crucial role in managing logistics activities and the coordination of relationships along the supply chain, as it is needed in humanitarian disaster relief operations that represent very complex logistics operations.

Among LSPs, the category of the so-called “integrator logistics provider” may designate those most appropriate for strategic partnerships with humanitarian organisations in relief actions. Logistics providers indicated as ‘‘integrators’’ offer “complex value-added solutions” with a high degree of personalization/modularization, exploiting their intangible assets, focused on organizational and managerial skills [2,51,52]: in particular, they are characterized by a high “customer adaptation” ability [53], as being more “non-physical asset-based” [54], and offering “solutions” with “wide value-added logistics services” [55]. By virtue of these qualities, the integrator “becomes a central point in the governance of the logistics network and has more strategic responsibility” [2] (pp. 32, 33). Sometimes they are termed as lead logistics providers [8]. Those LSPs have taken the initiative to propose themselves, with their logistics and supply chain management capabilities, as partners in humanitarian action [2,27].

3. Methodological Approach

To gain a deeper insight into the role of platforms in the involvement of the private sector—especially logistics businesses—in humanitarian action an emblematic case of cross-sector platforms was investigated.

Case study research is important in both logistics, which also provides detailed explanations of best practices [56,57,58], and in social sciences and management [59,60].

The emblematic example investigated is the platform of the Logistics Emergency Teams (LET) together with the lead of the Logistics Cluster of the United Nations, the World Food Programme (WFP).

The approach to the study of this case, based on the experience of the partnership between WFP and the LET companies, is qualified as explorative and qualitative, and it may represent an opportunity to inspire interpretative and/or explanatory future research based on it. A descriptive analysis has been chosen as an exploratory step that helps to explore singularities rather than looking for patterns within the data, given the uniqueness of the case analysed in this work.

The data collection is based on qualitative secondary published documents, both academic and professional, that directly refer to the WFP/LET partnership: on one side, academic papers that specifically analysed the case of WFP/LET, and also contained published interviews with members of WFP/LET, and, on the other side, institutional sources, such as websites, videos, reports, and public documents, that describe the initiative of the LET from the perspective of the partnership actors. Data arise from a variety of different sources, to ensure proper data triangulation: on one side, from academic publications that specifically analyse the initiative, mainly referring to the works of Cozzolino et al. in 2018 [61], Oglesby and Burke in 2012 [9], Stadtler and van Wassenhove in 2012 [62], Cozzolino in 2012 [2], and, on the other side, from the institutional Websites of the Logistics Cluster [63], United Nations World Food Programme [64], and Logistics Emergency Teams [65], and of the single companies currently composing the LETs partnership (Agility, UPS, Maersk, and DP World).

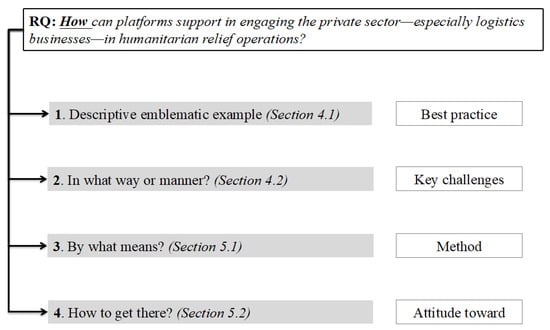

This investigation was based on a qualitative desk analysis and follows the logical scheme represented in Figure 1. The data obtained from the different documents/sources are systematically processed and organized, guarantying the validity and reliability of the research. The analysis aims at: synthetically describing the context when the platform was born, identifying actors and processes, and understanding how the specific investigated platform works (Section 4.1); assessing and operationalizing the characteristics of the platform, enhancing the engagement of the private sector in humanitarian relief operations, using the logical scheme of the key challenges described by Oglesby and Burke in 2012 [9] in their research (Section 4.2). This choice in particular is based on the consideration of the extensive and well-founded analysis by Oglesby and Burke [9], describing with a wide overview the topic of platforms investigated in humanitarian contexts.

Figure 1.

Logical scheme.

This kind of relationship investigated exemplifies “a platform for private sector–humanitarian collaboration” at a global level [9], and it is a way to “pioneer a new partnership model” as part of disaster response [62], as it is the first case of its kind in the world [63]. It is no coincidence that this initiative is the first of its kind and was born from the collaboration with WFP, the greatest expert in humanitarian logistics at the international level [49]. On the other side, there is a complex case of a multi-company partnership, changing its composition with time. The case in fact was chosen by virtue of its global importance and complexity, as it represents an emblematic example of a best practice platform in cross-sector humanitarian action: this case was the first (historically) and is still the only global cross-sector platform in logistics, collaborating in the preparedness, response, and reconstruction phases of the disaster management cycle, using core competencies. It was born under the auspices of the World Economic Forum in the wake of the 2004 Indian tsunami, nowadays still working and evolving around the initial platform idea.

4. An Emblematic Case of Global Platform in Humanitarian Action

4.1. World Food Programme and Logistics Emergency Teams: The Initiative

“The annual meeting of world economic leaders in Davos has become one of several platforms for [the] brokerage of public–private partnerships in the humanitarian field” [28] (p. 349). During the World Economic Forum (WEF) summit, United Nations agencies and WEF member companies declared to constitute an innovative initiative by international logistics providers, contributing by Logistics Emergency Teams (LET) intervening in disasters. The WEF facilitated the partnership initiative in 2005.

The LET currently consists of four large global logistics and transportation companies: Agility, UPS, Maersk, and DP World. They collaborate with each other to support pro bono the Logistics Cluster (LC) led by the United Nations World Food Program (WFP) during emergency responses to large-scale natural disasters.

The “Cluster Approach” (CA) is one of the major innovations powering the coordination capacity introduced in the United Nations systems. The CA was designated by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) and supervised by the Emergency Response Coordinator, as the main outcomes of Humanitarian Reform. Clusters are established to increase efficient and effective coordination among humanitarian actors in the relief efforts, identifying different key activity sectors/areas (technical areas, cross-cutting areas, and common service areas). Each cluster is assigned a lead agency within the UN system, which has leadership within the international humanitarian community in that particular sector/area. The Logistics Cluster is responsible for coordinating joint logistical activities in humanitarian emergency missions, ensuring timely and reliable logistical services—and related information—to the entire humanitarian community [63].

The lead agency for the LC is the World Food Programme, “because of its expertise in humanitarian logistics and its field capacity” [64]. The WFP is an executive member of the United Nations Development Group, a consortium of UN entities that aims to fulfil the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Moreover, it was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2020 for its efforts in providing food assistance in areas of conflict, and to prevent the use of food as a weapon of war and conflict. The WFP hosts the Global Logistics Cluster support team in its headquarters in Rome, Italy. WFP has thousands of dedicated employees with high levels of expertise and different transportation vehicles—trucks, planes, ships, helicopters, and amphibious vehicles—to ensure that they can reach those who need them most [64]. The WFP, engaged as an inter-agency logistics service provider, has decided to establish several agreements with both humanitarian participants and the private sector especially for serious disasters; in fact, much of the success of WFP in recent years has depended on the strength of its partnership with governments, other United Nations agencies, NGOs, and the private sector [2].

The LET “unites the capacity and resources of the logistics industry with the expertise and experience of the humanitarian community to provide more effective and efficient disaster relief” [65]. The LET partnership has lasted for more than 10 years: since it became operational, at the explicit request of the LC, the LET has responded on the field to 22 natural disasters and global crises, with its own means, people, skills, and key contacts on the basis of its networks and operations already existing in the place of emergency. It has also provided key information and analysis for Logistics Capacity Assessments (LCAs) to assist humanitarian organizations in emergency preparedness and response [65].

The greatest strength of LET lies in involving, in advance, all private and humanitarian members in the planning of their partnership in order to ensure an efficient and effective post-disaster response. The result is embodied in a series of pre-agreements and in an emergency plan ready to be activated in a few hours to support the relief efforts in the event of large-scale natural disasters (Olivia Bessat, Senior Manager, Global Agenda Council Team, World Economic Forum).

Over time, the LC has found it important to include an even more specific focus on preparation activities in its strategy. The preparedness phase is crucial to help strengthen the response phase and reduce the impact of new disasters. In particular, starting from 2016, following this focus, LET companies have increased their activities in this area with specific services and projects [65]. The LC has also asked the LET starting from 2017 to expand its support to other types of interventions. Before the expansion, the LET only responded to emergencies that were the result of large-scale natural disasters affecting more than 500,000 people. It now provides support in responding to sudden-onset natural disasters and to complex emergencies, health emergencies, slow-onset emergencies, and even the provision of support before an emergency [65].

Along these years of operating, the LET has provided humanitarian assistance in the following operations [65]: in 2019, cyclones Idai and Kenneth in Mozambique; in 2018 the Sulawesi earthquake and tsunami and the Java Pandeglang tsunami in Indonesia and refugee support in Bangladesh, Yemen, Syria, and Iraq; in 2016, Hurricane Matthew in Haiti; in 2015, the Gorkha earthquake in Nepal; in 2014, Ebola in West Africa and Typhoon Koppu/Landa in the Philippines; in 2013, Typhoon Haiyan/Yolanda in the Philippines; in 2012, Typhoon Guchol/Butchoy in the Philippines; in 2011, famine in the Horn of Africa and the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan; in 2010, an earthquake in Haiti and flooding in Pakistan; in 2009, an earthquake in West Sumatra and a typhoon in the Philippines; in 2008, tropical storms Fay in Haiti, Hanna and Ike in Gustav, and Cyclone Nargis in Myanmar; in 2007, earthquakes in Indonesia.

LET partners signal their commitment in the LET initiative in their sustainability sections of their institutional websites (see Table 1). They all have other experiences—outside of the Logistics Cluster request—in providing additional humanitarian support independently and bilaterally and in implementing other sustainability programs and projects, as reported on their institutional websites.

Table 1.

Logistics Emergency Teams (LET) initiative in business partners Web sites (Web sites accessed on 5 February 2021).

The LET is the first partnership of its kind, formalizing multi-stakeholder cooperation between private and humanitarian sectors. It remains one of the largest “public–private partnerships” launched and made operational by the WEF [65].

4.2. Analysis of the World Food Programme/Logistics Emergency Teams Partnership as a Global Cross-Sector Platform through the Lens of Oglesby and Burke’s Key Elements

After more than 10 years since its birth, it would be interesting to analyse the WFP/LET platform in comparison to each of the key challenges described by Oglesby and Burke in 2012 [9] in their research on platforms (presented in Section 2.1). This allows to articulate the description of the case through a classification of the humanitarian platforms deriving from the academic literature, also giving greater emphasis to the meaning and interpretation of the research data. A brief description of each aspect is provided below.

Referring to Point 1 (platforms may address complex disaster challenges that single organisations or partnerships are unable to overcome alone), the WFP/LET case shows that, even if it is not easy for organizations belonging to different sectors, “if two or more organizations can save more lives or ease more suffering by working together, they should seriously consider it” [66] (p. 35). Within the platform, joining forces between LSPs and humanitarian operators seems to provide concrete and important advantages in the success of complex relief interventions. Cooperation between two different sectors is not easy, but it is possible because they bring complementary resources by virtue of their mutual interests. As Athalie Mayo (the Global Logistics Cluster Coordinator) declares, “the scale and duration of both sudden onset, protracted and complex emergencies are too much for the humanitarian sector to respond to alone. Only through a strategic, predictable and sustainable cooperation with a variety of actors and crucially, the private sector, can these challenges be addressed” [67] (p. 2). This point revels that the coordination in the effort for humanitarian action is not easy because it engages very different players together, which have a high degree of heterogeneity, especially humanitarians and private companies, but not only, in terms of their culture, purposes, interests, mandates, skills, competences, etc. The topic of coordination is extremely important.

With reference to Point 2 (platforms can contribute to a strong focus on disaster risk reduction and on the preparedness phase), the WFP/LET case shows how important the phase of preparation is: “a successful response to a disaster is not improvised. The better one is prepared the more effective the response” [6] (p. 480). This platform develops knowledge internally based on a long logistics experience of tools and instruments from each LSP and through learning from relief operations that increase the virtuous loop of the learning process based on the “lesson learned” experienced on the field. Moreover, it assists agencies and governments to improve their preparedness for humanitarian crises, with mitigating logistics bottlenecks, capacity building, and the creation of networks and with structured valuable logistics information tools (such as the Logistics Capacity Assessment—LCA), acting at the global and also field levels. In 2016, in particular, the LC focused more on the phase of preparation and asked LET to follow this direction in their activities, which have proven to be key for a faster and more reactive response in case a disaster occurs [68]. Great attention is on preparedness that is the crucial phase to guarantee, through contingency and assessment planning, the successful of the response operation, saving lives. The preparation is not only centralized, but it is widespread locally among operators acting in the specific geographical area. Moreover, volunteers returning from humanitarian experience can transfer their knowledge to the local communities in which they use to work by increasing their degree of readiness in response to events of uncertainty.

WFP/LET are regulated by a strong and transparent procedure to guide intervention (Point 3—platforms may provide a clear access point for the engagement of the private sector in humanitarian action). Specific guidelines and agreements formalized by the UN community help direct the partnership. Furthermore, as emerges from an interview of a LET employee during a disaster relief operation: “We are in a very closed cooperation with WFP. We know each other and we know each other’s needs very well. So, in case of a disaster like this, we come together very quickly and we generate concrete plans” [2]. For example, in line with the members’ commitment to the “bigger picture,” the collaboration between LET members has seen UPS staff unloading the TNT planes to meet a request for logistics assistance from the LC. Moreover, this platform is also open to accept other LSPs interested in working in collaboration with the LC.

Even if it difficult to define and measure their impact, platforms are trying to improve this point (Point 4), and this specific platform communicates its results and projects. Annually, it publishes its annual report, and other documents and analysis, and shares facts and ideas at the Logistics Cluster Global Meeting with the partners involved or interested. It is not easy to assess the impact of a platform’s contribution, but they are working on it, e.g., with the performance and pertinence of the Monitor Logistics Cluster in the “Gaps and Needs Analysis.” More generally, a crucial aspect is about trying to measure the costs and outcomes/impact of the logistics services on the beneficiaries and what expected at the end of the overall intervention.

Members of this platform came together to provide useful logistics to support the humanitarian community, as mentioned in Point 5 (platforms may aggregate working members and their contributions to effectively provide useful services). For this type of platform with exclusive membership models, success is achieved through maintaining characteristics such as neutrality, transparency, and equity among members (the LET has a rotating Chair) and tight controls on the organisations permitted to join. Two employees of the platform after participation in the LET’s annual training explicitly declared on this point that, when they work together, they are all dedicated professionals with the same sense of community, even if they are competitors in commercial contexts: they feel like a team. This point reveals the need to have a useful service and product to be managed during the response phase, so that the errors that occurred in 2004 are not repeated: when for example, donations arrived that were not useful (even inappropriate ones) and occupied precious space in airports and warehouses, which could then not accommodate more useful items.

Referring to Point 6 (platforms may create and manage an information repository to learn how they can facilitate private sector engagement in humanitarian action), this platform has LC-WFP as its main collector of information. Moreover, it communicates through a rich institutional website where all the information useful for partnership is collected, and the contacts are indicated, with other actors involved, inside both the LC and WFP pages. On their website (LC, WFP, and LET), they collect annual reports, cases, and experiences from each voluntary member on the ground in blogs, interviews, research results, and other resources from the academic and professional literature. LET training takes place annually and prepares volunteers together with LC. Moreover, the platform is involved in the logistics training introduced by the LC (the LC runs and contributes to several training sessions aimed at developing the logistics response of the humanitarian community), implementing recommendations, best practices, and the lessons learned from previous relief operations. Shared information is the key factor for a concrete alignment and collaboration across inter and intra-organizational boundaries, assuring a virtually integration and a fully visibility along the supply chain. That is also useful to try to prevent mismatches and the so-called “Bullwhip” effect.

Point 7 refers to the characteristic of platforms that may contribute to develop linkages with governments for the members. In WFP/LET case, by virtue of their positioning in the global platform area of action, they may have a natural link to governments. For the moment, under the umbrella of the LC, the platform develops relationships with government entities and agencies across the different operations. This point underlines the importance of the relationships with the territory, in a bi-directional perspective, both from the platform to the local community, and vice versa from the local to the centralised responsibility; also because governments (host governments, neighbouring country governments, and other country governments) have the power to authorize operations after a disaster strikes.

Platforms need to be adaptive and sustainable in their evolving stages (Point 8): this platform was founded more than 10 years ago, but it has been able to renew itself and evolve in this context. The WFP/LET, under the support of the LC, have been created as a network of logistics actors, which are prepared to respond to emergencies and have been operational for more than 10 years, surviving and adapting in a very frequently changing context. The years since 2004 have seen a tailoring of the partnership that ensures their configuration and effective implementation [62]: Agility, DHL, TNT Express, and UPS started at the very beginning to investigate options to provide logistics-coordinated support to the humanitarian sector; in 2007, DHL chose to terminate its participation in the LET; in January 2008, the CEOs of the three companies formally announced the collaboration between them, the LET, and the LC at the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum; Maersk joined the LET in the following years; in 2014, there were three of them, Agility, Maersk, and UPS; in 2017, DP World also joined the team. This evolution underlines the character of the partnership of the LET and its modular matching with the WFP. The LET partnership appears itself to be a platform, so it might be possible to refer to the “platform-inside-a-platform” WFP/LET.

From a perspective considering the future (covered in Point 9—platforms need to work in new ways if the context requires changes, to remain relevant in future challenges), Athalie Mayo (the Global Logistics Cluster Coordinator) declared that “the innovative and inclusive spirit of the LET partnership provided a pioneering model for humanitarian and private sector collaboration,” and it is “essential to the Logistics Cluster” [67] (p. 2), also considering an increasing trend in the frequency and duration of humanitarian disasters that require being ready for new challenges. In 2017, the LC requested to expand the scope of the LET in the “complex emergencies” and in preparedness activities (as previously described). Prior to this expansion, the LET only participated in emergency responses that were the result of a large natural disaster affecting more than 500,000 people. Complex emergencies refer to crises of human origin that may intensify, for example, due to the various external dangers such as drought or the massive influx of refugees [68].

The considerations arising from this analysis seek to confirm the platform LET/WFP as a best practise in this context, even if with some aspects that might be implemented.

Commenting on the results of the research on the platform by Oglesby and Burke [9] and each correspondence with the initiative of WFP/LET, it is now possible to understand how platforms help in engaging the private sector, especially logistics businesses, in humanitarian relief operations.

5. Discussions and Implications

5.1. Orchestrating the Logistics Network

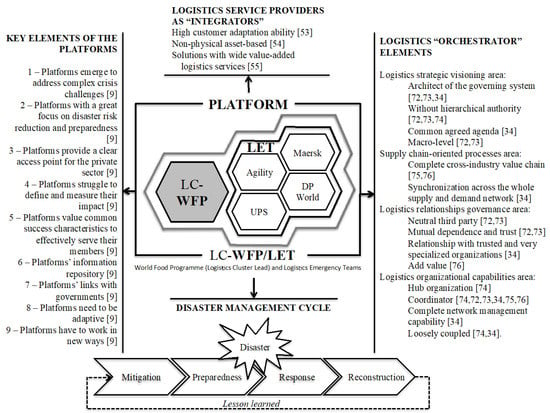

As described in the previous section, it is clear that WFP/LET represent a useful platform supporting the engagement of the private sector, especially logistics businesses, in humanitarian action since they provide a “place” that arranges the complementary contribution of professionals, resources, and activities in a stable organizational structure and makes the structure easily “reconfigurable” according to need [10,11].

In other words, the platform makes it possible to “orchestrate” the complex aid logistics network in response to emergencies [8]. The term metaphorically recalls the role of the symphonic orchestra maestro who composes the symphony, defining the timing and synchronisms of each musical element (as composer), and directs the individual contributions in the execution of the planned harmony (as conductor) [2,69,70,71]. The metaphor of the orchestra maestro can be transferred from the individual subject to organizations, referring to a more general combination of complementary resources for a common project [2,69,70,71]. It well describes the initiative of WFP/LET: the contribution of each element is an indispensable component of the overall performance. The idea of orchestration includes the fact that there must be an agreed-upon agenda that guides the achievement of supply chain goals of all participants in the supply chain [34].

The WFP/LET platform expresses its potential in the combinatory capacity of the two sectors—humanitarian and private—as an orchestra maestro, directing and organizing its logistic network. In fact, it seems to possess the relevant characteristics typical of the orchestrator that are fully transferable to logistics activities and appropriate for the WFP/LET platform. Thus, following a criterion of aggregation, it is possible to group the list of characteristics that are more relevant for a logistics orchestrator of a logistics network, according to four macro managerial areas [69], applied to the platform of this research:

- A logistics strategic visioning area that characterizes the orchestrator that:

- ○

- Includes the architect of the governing system [34,72,73];

- ○

- Is without hierarchical authority [72,73,74];

- ○

- Implements a common agreed agenda [34]; and

- ○

- Acts at a macro-level, not (necessarily) involved in managing the day-to-day operations of the service provider [72,73].

- A supply chain-oriented processes area that characterizes the orchestrator that:

- ○

- Is active in the complete (cross-)industry value chain [75,76]; and

- ○

- Has higher levels of synchronization across the whole supply and demand network [34].

- A logistics relationships governance area that characterizes the orchestrator that:

- ○

- Acts as a neutral third party [72,73];

- ○

- Is focused on mutual dependence and trust [72,73];

- ○

- Has a hands-off relationship with trusted and very specialized manufacturing organizations [34]; and

- ○

- Takes ideas from network partners and [adds] value by developing them further in their own organizations [76].

- A logistics organizational capabilities area that characterizes the orchestrator that:

- ○

- Acts as a hub organization [74];

- ○

- Is a coordinator [34,72,73,74,75,76];

- ○

- Has complete network management capability [34]; and

- ○

- Is loosely coupled [34,74].

Combining these characteristics of the emerging orchestrator role with key elements of the humanitarian platforms it is possible to more concretely understand how platforms, with their coordination function, can support the engagement of the private sector—especially logistics businesses—in humanitarian relief operations, and its potential for future research, as formalized in the framework in Figure 2. The issue of the responsibility for the coordination among the actors in the humanitarian supply chain takes on particular importance, since the adequate setting and management of the reciprocal interdependencies of the subjects involved become an essential requirement for the success of the entire supply chain and its operations. A coordination function that is mainly focused on three connected elements: logistics, communication, and knowledge.

Figure 2.

Platform framework: the Logistics Cluster-World Food Programme (LC-WFP)/Logistics Emergency Teams (LET) Partnership.

5.2. Moving toward New Challenges

Numerous important issues are combined in defining the complexity of the topic investigated in this paper and its relevance in the real context. However, some in particular, within this research, seem to emerge as the main guidelines, which define the direction to achieve, through the platform, full achievement in the engagement of the private sector—particularly of logistics companies—in humanitarian relief operations. They are the following, as also summarized in Table 2:

Table 2.

Practical implications.

- (a)

- To measure and report on relief operations results;

- (b)

- To foster cross-learning between commercial and humanitarian supply chains;

- (c)

- To manage complexity in humanitarian logistics and supply network.

The first (a) guarantees continuous improvement and allows to formalize the lessons learned from previous experiences, for the benefit of subsequent operations. Among various metrics, the measurements should control inputs, processes, outputs, outcomes and impact [77,78]. The most critical and important are outcomes (that reflect the benefits received by the recipients of the aid activities) and impact (that refers to the sustainable development results expected at the end of the delivered aid), but there are very few utilized in humanitarian activities, more often organizations arrive to the outputs (which refers to the direct products/services of a specific programme of activities) measurement [77,78].

The second (b) ensures that there is an exchange in complementary areas. In particular, the possibility to transfer knowledge experienced in a given sector to other area of application is also often used to boost the search for innovative solutions. The two sectors can learn from each other and build a process of transferring the best practices, thus a platform between companies and humanitarians can act as a kind of “learning laboratory” [5], with a multifaceted cross-sector perspective.

The third (c) ensures that the ability to respond is effective in a supply network that is extremely complex, considering at least the multitude of nodes (actors, facilities, etc.), links (relationships, activities, etc.) and interfaces (contact points), that constitute the network, with its structural components and dynamic interactions [79]. The interfaces are especially critical where there is a shift of responsibility that can create a discontinuity—at physical, operational and/or temporal level. Particularly, a complex network must be managed in a high uncertain context in response to disasters. The typical skills of the orchestrator are fundamental for the management of the complex humanitarian supply networks.

All of them contribute to the preparation of an “agile” supply chain in response to humanitarian disasters:

- (a)

- Humanitarian logistics metrics are essential to prove and measure the real agility of the response;

- (b)

- One potential area of cross-learning in the humanitarian context has only recently been identified by some authors in the agility of the supply chain [61];

- (c)

- The concept of agility goes beyond the level of an individual organization, having implications for the organizations within the supply network that are related to each other, providing entire agile supply chains [34].

Agility may be defined in the synthesis as “the capability to respond to unpredictable events in a simultaneous fast, effective, and flexible way and at a reasonable cost” [61] (p. 329). When agility is discussed in the humanitarian logistics and supply chain management context, it is mostly associated with its importance and usefulness during emergency relief operations, in the response phase [2,6,8,26,27,49,61]. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs has also underlined “agility” as a priority research theme [80].

Agility fits inside the framework of the platform, as it implies to be “event-driven”, “network-based”, “process-oriented” and “virtually integrated through shared information” [8].

An agile supply chain may guarantee a responsive, resilient, and “anti-fragile” [81] response to uncertainty. Focusing on this point, its crucial impact emerges, not only in strictly humanitarian contexts, but beyond: it has an influence on all over the wider and more frequent situations of the commercial chains that are faced with general uncertain, risks, disruptions, more or less serious, from a supply business interruptions to even extreme pandemic events, such as the one we are facing right now [82]. The experience of a humanitarian platform capable of partnering the two sectors together responding to disasters should be taken as an inspiration for the commercial chains coping with general critical events.

Thus, in this way, sustainable supply chain management broadens the perspective of an organization and its supply chain in a sense of a more strategic, systemic and holistic view, going beyond a formal—accounting, social (and environmental)—responsibility, imposed by rules and regulations, and “working toward a triple helix for value creation, a genetic code for tomorrow’s capitalism, spurring the regeneration of our economies, societies, and biosphere” [36].

6. Conclusions

This contribution aimed at investigating of the opportunity for companies to engage in the humanitarian relief operations throughout the platform. The literature and the analysed emblematic example reveal that platforms have the potential to make important contributions to facilitate an effective engagement of the private sector in humanitarian action.

The preliminary results that emerge from this research can be interesting and useful for both academics and professionals in the two sectors, profit and non-profit. In fact, first of all, the use of the platform makes it possible to concretely help people in need by reaching them through the various humanitarian relief operations; moreover, it can be a good basis for a constructive dialogue to build new projects to achieve further sustainable goals.

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has aggravated the context of the global crisis, and the need for coordination arises as an even more burning topic. As declared in the “Financial Times” (22 April 2020), the pandemic crisis has underlined the need to work together for the vital safety of single actors and entire supply chains: transforming their supply chains to “just in case” models (FT, 2020). The platform investigated in this research sustains the supply chains in this direction, through concrete and effective coordination, and it may be of example for other realities, in humanitarian contexts as well as in commercial ones.

A message contained in this paper is that “the commitment to breaking down the barriers to much closer collaboration across organizational boundaries” [8] (p. 9) is growing to also guarantee an agile supply chain in response to disasters, based on a platform solution.

Specifically, the “platform” investigated in the present paper is between the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) and the Logistics Emergency Teams (LET), composed of four global leading logistics providers. The WFP/LET platform represents an emblematic example in this research area, as a platform of high logistics competencies, for many reasons, at least: it is a cross-sector platform (between humanitarians and the private sector), it is a multi-company partnership (it involves different leading logistics providers at global level both competitors, in the commercial supply chains, and partners, in the humanitarian context), it is focused on delivering complex logistics services along the humanitarian supply chain, it is recognized at a global level, it is the first (historical) case and still the only global cross-sector platform in logistics, collaborating in preparing for and responding to huge disasters, and still surviving and developing its activities along the time, it was born under the auspices of the World Economic Forum, and its humanitarian partner, the WFP, is the most authoritative in the global humanitarian logistics context: it is the leader of the Logistics cluster, and it has experience with high logistical competences for the entire humanitarian system; moreover it was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2020, and it is an executive member of the UN Development Group for sustainability.

This study, despite having provided some useful insights on the topic, needs to be deepened, especially in its empirical investigation, with an on-field analysis, which requires a further detailed examination that extends the understanding of platform opportunities and also the criticalities for private sector–humanitarian collaboration. This could be achieved by questionnaires for and semi-structured interviews with the professionals engaged in the platform in its different activities, valorising the analysis of primary data.

Funding

The Author used her University research funds for covering the costs to publish in open access.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments which helped to improve the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Thomas, A.; Lynn, F. Disaster relief. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 114–126. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzolino, A. Humanitarian Logistics: Cross-Sector Cooperation in Disaster Relief Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kent, R.; Burke, J. Commercial and Humanitarian Engagement in Crisis Contexts: Current Trends, Future Drivers; King’s College London: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton, O.; Stadtler, L.; van Wassenhove, L.N. Private-Humanitarian Supply Chain Partnerships on the Silk Road. In Managing Supply Chains on the Silk Road: Strategy, Performance, and Risk; Haksöz, C., Seshadri, S., Iyer, A.V., Eds.; CRC Press: West Palm Beach, FL, USA, 2012; pp. 217–238. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter, R.M. From spare change to real change. The social sector as beta site for business innovation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1999, 77, 122–132. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wassenhove, L.N. Humanitarian aid logistics: Supply chain management in high gear. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2006, 57, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burcu, B.; Beamon, B.M.; Krejci, C.C.; Muramatsu, K.M.; Ramirez, M. Coordination in humanitarian relief chains: Practices, challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 126, 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher, M.; Tatham, P. Humanitarian Logistics: Meeting the Challenge of Preparing for and Responding to Disasters; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Oglesby, R.; Burke, J. Platforms for Private Sector: Humanitarian Collaboration. In Platforms for Private Sector: Humanitarian Collaboration; King’s College London: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative platforms as a governance strategy. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2018, 28, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciborra, C.U. The platform organization: Recombining strategies, structures, and surprises. Organ. Sci. 1996, 7, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawer, A.; Cusumano, M.A. Industry platforms and ecosystem innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobides, M.G.; Cennamo, C.; Gawer, A. Towards a theory of ecosystems. Strat. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 2255–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, S.; Lusch, R.; Reynoso, J.; Saviano, M.; Spohrer, J. Systems, networks, and ecosystems in service research. J. Serv. Manag. 2016, 27, 652–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, G.; Spens, K.M. Humanitarian logistics in disaster relief operations. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2007, 37, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyöngyi, K.; Spens, K. Identifying challenges in humanitarian logistics. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2009, 39, 506–528. [Google Scholar]

- Altay, N.; Green, W.G. OR/MS research in disaster operations management. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 175, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, S.J.; Beresford, A.K.C. Critical success factors in the context of humanitarian aid supply chains. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2009, 39, 450–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Zbinden, M. Marrying logistics and technology for effective relief. Forced Migr. Rev. 2003, 18, 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A. Why logistics? Forced Migr. Rev. 2003, 18, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Cottrill, K. Preparing for the worst. Traffic World 2002, 266, 15. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva, F.N. Providing special decision support for evacuation planning: A challenge in integrating technologies. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2001, 10, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D. Logistics for disaster relief: Engineering on the run. IIE Solut. 1997, 29, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jahre, M.; Jensen, L.; Listou, T. Theory development in humanitarian logistics: A framework and three cases. Manag. Res. News 2009, 32, 1008–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maon, F.; Lindgreen, A.; Vanhamme, J. Developing supply chains in disaster relief operations through cross-sector socially oriented collaborations: A theoretical model. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2009, 14, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasini, R.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. From preparedness to partnerships: Case study research on humanitarian logistics. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2009, 16, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasini, R.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Humanitarian Logistics; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Andonova, L.B.; Gilles, C. Business–humanitarian partnerships: Processes of normative legitimation. Globalizations 2014, 11, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, A.; Wankowicz, E.; Massaroni, E. Logistics service providers’ engagement in disaster relief initiatives. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The competitive advantage of corporate philanthropy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Koberg, E.; Longoni, A. A systematic review of sustainable supply chain management in global supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 1084–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaroni, E.; Cozzolino, A.; Wankowicz, E. Sustainable supply chain management: A literature review. Sinerg. Ital. J. Manag. 2015, 98, 331–355. [Google Scholar]

- Closs, D.; Speier, C.; Meacham, N. Sustainability to support end-to-end value chains: The role of supply chain management. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M. Logistics and Supply Chain Management; Pearson: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone Publishing Ltd.: Mankato, MN, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. 25 years ago I coined the phrase “triple bottom line.” Here’s why it’s time to rethink it. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2018, 25, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby, A.; Leat, M.; Hudson-Smith, M. Making connections: A review of supply chain management and sustainability literature. Supply Chain Manag. 2012, 17, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaziulusoy, A.I.; Boyle, C. Proposing a heuristic reflective tool for reviewing literature in transdisciplinary research for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. Environmental sustainability in the service industry of transportation and logistics service providers: Systematic literature review and research directions. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 53, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, A.; Pati, R.K.; Padhi, S.S.; Govindan, K. Evolution of sustainability in supply chain management: A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, H.; Jones, N. Sustainable supply chain management across the UK private sector. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Muller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M.; Shevchenko, A. Why research in sustainable supply chain management should have no future. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 50, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, W. Ethical and Sustainable Sourcing: Towards Strategic and Holistic Sustainable Supply Chain Management. In Decent Work and Economic Growth; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, A.; LaGuardia, P.; Srinivasan, M. Building sustainability in logistics operations: A research agenda. Manag. Res. Rev. 2011, 34, 1237–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, S.; Beresford, A.; Whiting, M.; Banomyong, R. The 2004 Thailand Tsunami Reviewed: Lesson Learned. In Humanitarian Logistics: Meeting the Challenge of Preparing for and Responding to Disasters; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2011; pp. 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A.; Kopczak, L. From Logistics to Supply Chain Management: The Path Forward in the Humanitarian Sector; Fritz Institute: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzolino, A.; Rossi, S.; Conforti, A. Agile and lean principles in the humanitarian supply chain. J. Hum. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2012, 2, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirstin, S.; Scott, P.S.; Fynes, B. (Le) agility in humanitarian aid (NGO) supply chains. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2010, 40, 623–635. [Google Scholar]

- Marasco, A. Third-party logistics: A literature review. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 113, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selviaridis, K.; Spring, M. Third party logistics: A literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2007, 18, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz, S.; Alfredsson, M. Strategic development of third party logistics providers. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2003, 32, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, G.; Virum, H. Growth strategies for logistics service providers: A case study. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2001, 12, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, M.; van Laarhoven, P.; Sharman, G.; Wandel, S. Third-party logistics: Is there a future? Int. J. Logist. Manag. 1999, 10, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellram, L.M. The use of the case study method in logistics research. J. Bus. Logist. 1996, 17, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Aastrup, J.; Halldorsson, A. Epistemological role of case studies in logistics. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 746–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, C.; Tsikriktsis, N.; Frohlich, M. Case research in operations management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, E.; Appelbaum, S.H. The case for case studies in management research. Manag. Res. News 2003, 26, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, A.; Wankowicz, E.; Massaroni, E. Agility Learning Opportunities in Cross-Sector Collaboration: An Exploratory Study. In The Palgrave Handbook of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 327–355. [Google Scholar]

- Stadtler, L.; van Wassenhove, L.N. The logistics emergency teams: Pioneering a new partnership model. Insead Case Study 2012, 10, 2012–5895. [Google Scholar]

- Logistics Cluster. Available online: http://www.logcluster.org (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- World Food Programme Awarded Nobel Peace Prize. Available online: https://www.wfp.org (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Logistics Emergency Teams. Available online: https://logcluster.org/logistics-emergency-team (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- McLachlin, R.; Larson, D.P.; Khan, S. Not-for-profit supply chains in interrupted environments: The case of a faith-based humanitarian relief organisation. Manag. Res. News 2009, 32, 1050–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logistics Emergency Team. Annual Report. 2019, pp. 1–13. Available online: https://logcluster.org/document/let-annual-report-2019 (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Logistics Emergency Team. Annual Report. 2018, pp. 1–8. Available online: https://logcluster.org/document/let-annual-report-2018 (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Cozzolino, A. Operatori Logistici; Wolters Kluwer: Milano, Italy, 2009; Volume 87. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzolino, A.; Vakharia, A.J. 4PL’s as “Orchestrators” of Logistics Networks. In Proceedings of the POMS Annual Meeting, Dallas, TX, USA, 4–7 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzolino, A.; Vakharia, A.J. 4PL-Providers as “Orchestrators” of Logistics Networks. In Proceedings of the Special Conference of Strategic Management Society (SMS), New Frontiers in Entrepreneurship: Strategy, Governance, and Evolution, Catania, Italy, 23–25 May 2007; pp. 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bitran, G.R.; Gurumurthi, S.; Sam, S.L. Emerging trends in supply chain governance. MIT Sloan Res. Pap. 2006. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=882086 (accessed on 3 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Bitran, G.R.; Gurumurthi, S.; Sam, S.L. The need for third-party coordination in supply chain governance. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2007, 48, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanaraj, C.; Parkhe, A. Orchestrating innovation networks. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, L. Concept and evolution of business models. J. Gen. Manag. 2005, 31, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterhuber, A. Value chain orchestration in action and the case of the global agrochemical industry. Long Range Plan. 2002, 35, 615–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatham, P.; Hughes, K. Humanitarian Logistics Metrics: Where We Are and How We Might Improve. In Humanitarian Logistics: Meeting the Challenge of Preparing for and Responding to Disasters; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2011; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Abidi, H.; De Leeuw, S.; Klumpp, M. Humanitarian supply chain performance management: A systematic literature review. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2014, 19, 592–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snehota, I.; Hakansson, H. Developing Relationships in Business Networks; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- L’Hermitte, C.; Tatham, P.; Bowles, M.; Brooks, B. Developing organisational capabilities to support agility in humanitarian logistics. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 6, 72–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, N.N. Antifragile: Things that gain from disorder. Math. Comput. Educ. 2012, 47, 238. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, T.; Vakil, B. Coronavirus is Proving We Need More Resilient Supply Chains. Available online: https://hbr.org/2020/03/coronavirus-is-proving-that-we-need-more-resilient-supply-chains (accessed on 5 March 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).