1. Background

Food security can be broadly defined as people having consistent access (physically, socially, and economically) not only to enough safe and nutritious food but also culturally appropriate food that meets their dietary needs, so that they can lead active healthy lives [

1]. Food insecurity, by contrast, refers to a lack of access to such food [

2]. Food security is crucial to health and has four dimensions (access, availability, utilisation, and stability) and is often less about food availability than issues that reduce its accessibility (affordability, location, and transport) [

1,

3,

4]. In Australia, the latest the Australian Health Survey (AHS) estimated that overall, 4% of Australian households ran out of food, with about 1.5% going without food when they could not afford it [

5]. Such figures are low compared to prevalence elsewhere. Indeed, Australia was ranked sixth in 2017 according to the Global Food Security Index (GFSI) [

6]. Nevertheless, the AHS results mean approximately 861,000 people aged over 2 years ran out of food and were unable to buy more at least once in the previous year. This affected younger persons more significantly, i.e., 5.9%, or 1,270,000, of those between 2 and 18, and 3.5%, or 753,400, of those aged 19 and over [

5]. This could reflect a more difficult situation existing within families. Although overall food insecurity is low among the Australian population generally, other studies applying different tools have reported a higher prevalence of food insecurity among various population groups [

7], particularly Indigenous populations [

8], low-income families [

9], and refugees and migrants [

10]. A similar situation exists among such population groups in other high-income countries [

3,

4,

11,

12].

Food insecurity (with or without hunger) occurs in disadvantaged urban areas where culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities and/or low income populations are concentrated [

7,

13]. Migrant families tend to congregate where possible, the location often dictated by affordability [

14,

15]. Such proximity also increases their ability to maintain family ties and culture, to enjoy the society of people from similar background and sharing a language, and to obtain easier access to culturally suitable foods [

16].

People from different cultural backgrounds have different food patterns [

17,

18]. Cultural food preferences might prove a barrier to food security for migrant cultural or religious minorities for two reasons: the added cost involved in physically accessing the foods and the cost of the foods themselves [

13,

19]. Such foods may be imported and present a higher purchase cost than locally produced alternative (but culturally unacceptable or unfamiliar) products.

Maintaining religious and cultural practice is important to many migrants, including Muslims. Although Muslims were among the 18th century settlers in Australia—their number increased with the 19th century explorers’ use of ‘Afghan’ cameleers and there was even earlier Makassan interaction with Indigenous populations in the far north of the continent [

20]—their presence increased markedly in the 20th century, especially since the 1960s and 1970s, with a large number arriving initially from Lebanon [

21]. Muslim Australians come from a variety of cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Many are from Asia (e.g., Turkey, Afghanistan, Bangladesh), while others are from Europe (e.g., Bosnia-Herzegovina), with Arabs from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) (e.g., Iraq, Iran) comprising approximately 20% of the total [

22]. These places of origin often reflect parts of the world troubled by internal faction fighting or war, with Australia representing a place of refuge for both refugees and migrants. Thus, by 2016, 604,200 Australians, or 2.6% of the population, identified as Muslims, up from 476,290 (or 2%) in 2011 [

23]. This includes first generation migrants and later generations (that from a migrant background).

Among the most recent arrivals are those from Libya. Although the Libyan population includes families who have resided in Australia for over two decades [

24,

25], their number was boosted by a number who entered the country of their own volition as students but were then compelled to seek protection during ongoing conflict that began with a revolution in 2011 in their homeland [

26].

For observant Muslims, ensuring that food is

halal is central to their religious practice. While some in the Australian community are familiar with the concept, many are not. This can cause confusion in terms of food production for Muslim consumption, not only on a commercial manufacturing and sales basis, but also for food preparation and sale in restaurants and cafes. The term

halal refers to foods that are lawful or permitted under Islamic law [

27], that is, foods that conform to the dietary food standard prescribed in the Qur’ān (Islam’s holy scriptures).

Haram refers to foods that are not permitted or are forbidden and are not be consumed by observant Muslims. Islamic law also dictates the approved method of slaughter, without which, an otherwise acceptable food becomes

haram [

28]. Excluded products include blood from any meat, any porcine product (including emulsifiers, gelatine, and rennet), and alcohol [

27]. The admixture of even minute quantities of elements that are

haram to products renders those foodstuffs unacceptable. Doubt in this space can prevent product purchase and impede consumption, especially in the absence of accurate labelling or confidence in that labelling.

Migrant families face other difficulties regarding food security. Nutritional labelling on food packaging provides important information to consumers at the point of purchase and plays an important potential role in promoting healthy food choices and eating behaviours. However, it should be noted at the outset that such labelling is largely language dependent [

29]. This reduces its value for migrant or refugee families not fluent in English (and the specific vocabulary of nutrients) or unfamiliar with how to ‘read’ the nutrition tables on packaging. Language facility also affects food preparation of unfamiliar foodstuffs and unfamiliar modes of food preparation [

30]. A major Canadian study found that members of one Arabic speaking community (Iraqi) reported improved diet due to their ability to read labels, which had increased since migration [

31]; however, generally, labelling was a problem for most CALD community members in high income westernised countries that were the subject of the study.

In Australia, there have been no specific research papers published related to Arabic Speaking Immigrants and Refugees (ASIR) and nutrition [

31]. Moreover, a recent review suggests that the comprehension of food security is generally low among MENA migrants in high income countries [

32]. MENA migrants maintain their ethnic identities by eating specific religious and culturally related foods [

17]. There is a substantial overlap between ASIR and MENA migrant populations. Given the number of such migrants and refugees entering the country, we believe an exploration of the food security or food adequacy status among minority groups from different CALD backgrounds (particularly ASIR communities) in Australia could contribute to the knowledge of issues around household food insecurity in such groups. This research seeks to do this amongst Libyan migrant families. Despite the population’s high level of education and understanding of food labels, food insecurity remains a problem among Libyan migrants [

33].

Recent

quantitative research on the level of food insecurity among Libyan families in Australia revealed that 72.7% of participants experienced food insecurity linked to household size, food stores location, food store type, and food costs. In addition, 35.8% of families reported inadequate comprehension of food labels [

33], which impeded their purchasing choices and was strongly associated with a number of socio economic variables [

33]. Another study among this population in Australia found that 64.4% had an income of less than AUD 42,000 [

34]. This compares with the average Australian taxpayer who earns approximately AUD 63,000 [

35]. Additionally, as the majority of Libyans are Muslim [

24], it can be hypothesised that they may desire to follow the dietary requirements (outlined above) that characterise their religious practice. This might also affect their food security. There has been no previous attempt to explain how these socioeconomic and cultural factors may influence their food security. More importantly, no prior research has reported on Libyan migrant food security perceptions, experiences, and needs. Thus, this paper aims to investigate food security among Libyan migrant families in Australia

qualitatively, exploring as many aspects of the issue as possible, including access to affordable foods that meet their cultural and religious needs, food label usage, the association between food label knowledge and food security, and the strategies migrants adopt in relation to food security and food labelling.

Theoretical Framework

This paper is situated within a food and nutrition security framework which provides a pragmatic lens for examining the fundamental elements of food security [

36]. Conceptually, food security has four primary pillars: accessibility, availability, utilisation, and stability [

37]. Access is achieved when people have sufficient resources (physical and economic) to obtain appropriate foods for a nutritious diet through purchase or own production. Availability is ensured if there is a consistent supply of such food. Adequate utilisation refers to the ability of the human body to convert food to nutrients sufficient to prevent malnutrition. Such consumption is moderated by a person’s nutrition knowledge and access to that knowledge [

36,

37]. Food utilisation should not be discussed only from a biological perspective. It reinforces family and social ties. Relationships and social networks are also critical for sharing food, food-related knowledge and skills, and food traditions that distinguish cultural communities [

38,

39]. These can be centred on ethnocultural background, health preferences (e.g., vegetarianism), and/or religious beliefs. Food and nutrition security can be achieved only when sufficient culturally adapted food is available within households and communities [

2]. Stability influences the other food security dimensions (availability, access, and utilisation). Stability (of supply and access) refers to individuals’ and the community’s ability to obtain food over time [

37]. Positive outcomes of food and nutrition security can include consumption of healthier foods, reduction in nutritional vulnerability, positive attitudes toward food preparation, retention of cultural food knowledge, and use of more sustainable food production methods [

36].

2. Methods

Methodologically, we adopted the phenomenological framework [

40]. The framework justifies the data collection method used to examine the lived experience of Libyan migrants residing in Australia. The use of a methodological framework allows appropriate data interpretation and maintains the quality and reliability of research [

40]. As this study involves examining the lived experience of food security among Libyan migrants in Australia, the phenomenological framework will be employed, as it has the ultimate aim of ‘understanding and describing the participants’ experiences of their everyday world as they see it’ [

41]. To have a deeper understanding of a person’s lived experience of a particular phenomenon, the participants must have a first-hand lived experience rather than a second-hand experience [

40]. To satisfy this intention, that is, in order to ‘see what the participant would see’, Libyan migrant families were recruited to generate a deeper and greater insight into their experience of food security, and perspectives of the ways that they understand their lived experience [

41].

Based on the phenomenological framework, we used the in-depth interviewing method for data collection. This kind of interaction between participant and researcher generates the required study data [

41]. Its aim is to explore the inner perspective of participants by capturing their experiences and their thoughts about, and feelings towards, a particular phenomenon [

40]. As this study explored families’ food security, in-depth interviews allowed us to see the situation from their point of view on food experiences through their lived experience, including how they coped with their food shortages. Furthermore, the purpose of conducting in-depth interviews is to interpret the meaning of a described phenomenon; additionally, it is a useful way to supply answers to questions about respondents’ experiences and feelings [

40,

42]. As this study also aimed to understand the meaning of food security to Libyan migrant families, in-depth interviews were adopted as these were considered the most appropriate method to meet the study’s objectives.

2.1. Participants and Recruitment Method

This paper is a part of a larger mixed-methods study on food security among Libyan migrants in Australia. The Libyan Embassy and the Australian Libyan Association assisted with the recruitment of members of the Libyan migrant community. The Embassy first contacted migrants by email and invited them to participate via a link on that invitation. This was supplemented by an online version of the invitation, linked to social media presences of Libyan immigrant groups (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp). Data collection was undertaken between October 2019 and February 2020. Participants were drawn from the 500 Libyan migrant families currently estimated to be living in Australia [

26]. Respondents were asked whether those who conducted most of their household’s food shopping would be willing to participate in an interview. Forty indicated their willingness to participate. We contacted them via email and SMS in Arabic and English, but only 27 responded. Voluntary participation at this stage may have indicated responses would be from those with a greater willingness to answer fully any questions [

43]. We contacted them by phone and arranged an interview (in person or zoom), its time and location. Participants consented to participation either in writing or orally. Saturation theory was adopted to determine the number of participants. Saturation is described as the point at which new themes are unlikely to be constructed from subsequent interviews, indicating that participant recruitment can be terminated [

43]. Recruitment of participants continued until little or no new information could be collected [

43]. Saturation point was reached at 20 interview participants. However, another 7 interviews were conducted to ensure that no further themes could be constructed, and we could be confident that we had achieved data saturation.

2.2. Procedures

The first author, R.M., performed all interviews with each family representative (although A.A. also attended the first three interviews to ensure interviews were conducted in accordance with appropriate interview procedures). Each interview began with a conversation on interviewee’s feelings about living in Australia to put the participant at ease. The interviewer referred to the guide to ensure the same topics were covered in each interview (

Table 1).

Either face-to-face or ‘zoom’ interviews were conducted with representatives of families residing in several Australian states to identify ways of ensuring Libyan migrants could access food consistent with their lifestyles and religious choices. Participants were invited to select the mode they felt more comfortable with. Both approaches were appropriate as they enabled participants to feel comfortable in sharing their personal experiences and feelings about their food access, availability, affordability, and utilisation in a private setting and at a time that was convenient to them. We conducted 11 face-to-face interviews and 16 Zoom interviews. Interviews took between 60 and 90 min.

Prior to the start of the in-depth interview, participants were introduced to the research and the purpose of the study, with their involvement in the study explained. Participants were then asked to sign a consent form to indicate that their informed consent had been given. Sociodemographic data were collected from each participant prior to commencement of the in-depth interview. With the participant’s approval, the interview was recorded using a portable electronic recording device and saved as a secure, password-protected MP3 file on the first author’s computer. The interviews took place at a location where the participants felt most comfortable. This was most often the participant’s home. Interviews were carried out using a topic guide (

Table 1) containing open-ended questions.

A token reward of a

$50 gift voucher was given to each participant upon the completion of the interview to compensate for time taken to participate in the research [

43,

44].

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for data analysis. The audio recordings of the interviews were first transcribed verbatim. For interviews where participants chose to respond in Arabic, the material underwent an additional step, that of translation from Arabic to English. This was undertaken by a professional translator, but further revised by the Arabic/English bilingual first author. Where possible linguistic errors occurred in the transcripts, further clarification was sought from the interviewees as meaning-making and meaning-sharing processes. All participants were later provided with the researcher’s interpretation of tentative themes to ensure that the transcribed data had been interpreted accurately. This material had then been through the process of Arabic–English–Arabic translation. Pseudonyms were substituted for each interviewee name, but their genuine location was indicated. These data were then coded, and themes identified from the transcriptions.

2.3. Data Analysis

Thematic analysis method was utilised to analyse the data [

43]. A thematic analysis involving an inductive approach was used to identify and analyse contextual patterns and themes within the data [

43]. Analysis was conducted in two stages: coding and identifying themes. For coding, transcripts were uploaded to the qualitative data management software Quirkos [

45]. The first author (R.M.) familiarised herself with the raw data through her initial reading of the transcripts line-by-line several times to generate meaningful paragraphs and statements which could be coded [

40]. Codes with similar meanings were then grouped together to form themes and sub-themes [

43].

Two researchers (R.M. and P.L.), who are trained in qualitative research, coded the transcripts and identified themes and sub-themes from the data [

43]. The codes, themes, and sub-themes were verified by P.L. and A.A., who selected and read sub-sections of the transcripts to confirm the codes and themes. Regular team meetings were held to discuss the themes and reach consensus.

2.4. Rigour

The member checking method was used to ensure the accuracy of the findings [

41]. The process of the interviewees checking the material took place at two levels. First, after the interviews had been audio recorded and transcribed verbatim for data analysis, all participants were provided with the researcher’s tentative themes and interpretation to ensure that the transcribed data had been interpreted accurately. Member checking is best done with polished interpreted data, such as the patterns, subthemes, and themes that arise from the data, rather than by providing the actual transcripts to participants [

44]. These interpreted data allow participants to comment on the findings and the researcher’s interpretations of their own and others’ quotes via email. The participants can either confirm or deny the accuracy of the interpreted data to ensure it reflects their views, feelings, and experiences, thus either supporting or challenging the researcher’s understanding [

42]. Secondly, responses were reviewed where certain sections of transcript appear unclear to a researcher while coding. This form of member checking ensures transcript accuracy. The peer review method was also used. Each interview was coded systematically and checked by the second and third researcher [

41].

3. Results

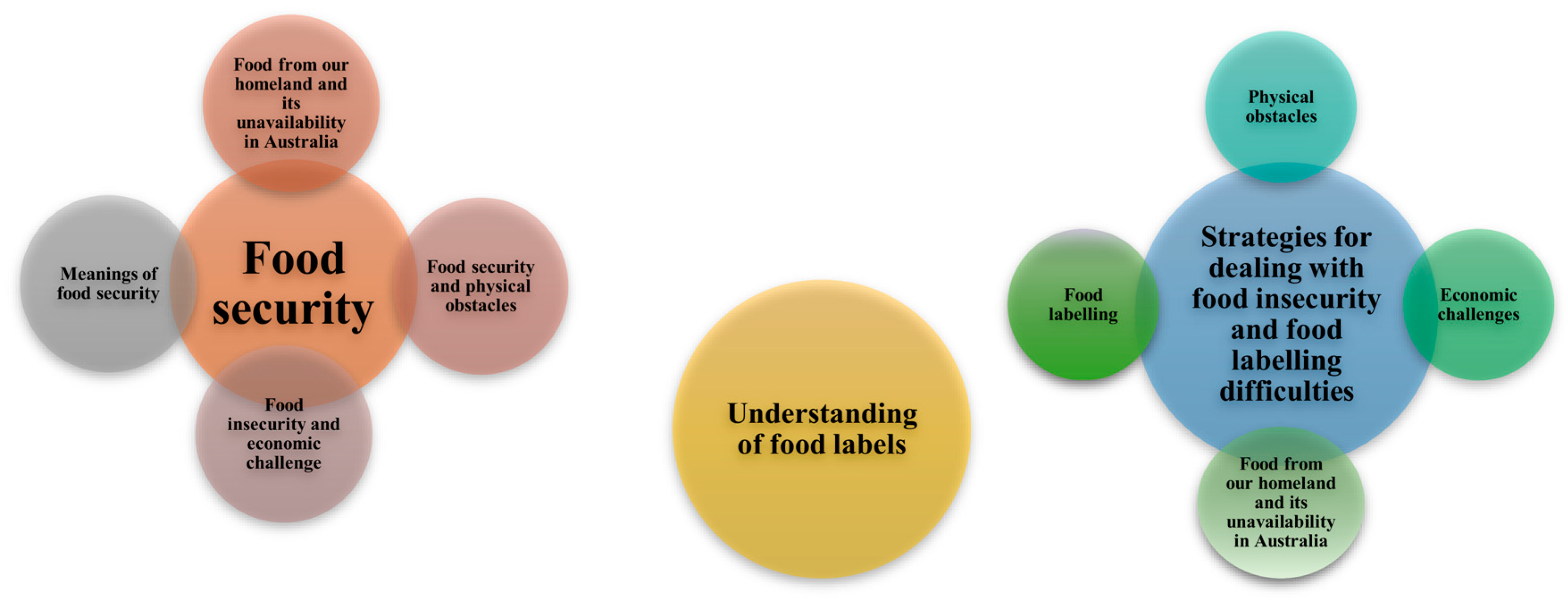

The research results are presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 1 below, with the various themes identified then outlined.

Table 2 illustrates the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants, while

Figure 1 illustrates the thematic structure of the findings and provides a visual representation of the three major themes (food security, understanding of food labels, strategies for dealing with food insecurity, and food labelling difficulties), the sub-themes, and their interconnectedness, as determined by qualitative analysis. The themes and subthemes are illustrated with verbatim quotations from participants.

3.1. Theme 1: Food Security

3.1.1. Meanings of Food Security

Food security has different meanings to or emphases for the various participants in this study. For the majority, food security is associated with food safety, that is, that the food was ‘clean’ and uncontaminated, had been stored properly (e.g., refrigerated if required), was not beyond the expiry date, and so able to be safely eaten. For others, food security means not being hungry and being able to afford the food they needed. In Arabic, there is an expression, which, in translation refers to ‘food enough to close the mouth’, that is, enough food to stop people feeling hungry but not necessarily the food one’s body needs for healthy living or the food people desire.

I think food insecure people are those who are undernourished, people who do not eat enough food or may starved of the right nutrition… However, I support myself and my family from the work, so I have not been struggling to the point of hunger.

(Ziyad, Melbourne)

For others, food security meant ease of access to quality food, its availability, and its affordability.

I think food security means that me and my family have financial security so we can afford to buy balanced and healthy food because unhealthy food is cheap to buy in Australia. Food security is all about being able to have a balanced diet full of fresh fruit and vegetables and good protein.

(Aziza, Wollongong)

Importantly, most participants mentioned that food security meant having food of sufficient quality, and that there was easy access halal food for themselves and their family, as this was central to their religious and cultural practice. Ensuring that food is halal is the everyday concern of observant Muslims and guides food consumption, including necessities such as meat and cheese, and discretionary items such as pastries and cake, and processed foods. Interviewees noted that this was important in terms of their families’ food security. Foods’ cultural suitability, including meeting religious requirements (i.e., halal), was important to many participants and formed part of their understanding of foods to which they needed security of access, whether in urban or regional areas.

In my opinion to be food secure, halal food should be clearly available in big supermarkets—easy access in the same shop [where] we do the other shopping…. This would be much easier and make me feel very happy.

(Shahd, Wollongong)

Traditional cultural food also occupies an important role in migrant lives, and its lack detracts from their overall sense of wellbeing.

We find whatever we want to eat [in terms of halal] and we can manage but we can’t find any of our favourite foods in restaurants or supermarkets or Asian food stores so, as I said, we go for easy options, what is available.

(Adel, Hobart)

The lack of familiar foods perpetuates their sense of being ‘a stranger in a strange land’; whereas access to familiar and culturally appropriate foods helps migrants feel ‘more at home’.

3.1.2. Food Security and Physical Obstacles

Most families living in urban areas (Sydney, Melbourne) did not find food access an issue. They shopped at the major supermarkets (such as Woolworths and Coles) and the traditional middle eastern grocery shops close to their homes. This enabled them to find a diversity of products and satisfy their cultural food needs but travelling outside of the city could prove problematic.

We always have trouble finding suitable food when we travel… It’s not a problem when we are at home in Sydney but, yes, when we travel, we struggle to find suitable meal … one we really like or suits our religion, but we usually pack light food, for example, bread and cheese.

(Juli, Sydney)

Families from regional areas faced difficulty in sourcing culturally suitable foods due to lack of proximity of appropriate shops to their dwelling and the unavailability of transport (private or public). For some, the distance to a bus stop or train station was too burdensome.

We don’t have a halal butcher in our area, so we have to drive 2 hours every month to Brisbane to get our halal meat (whole lamb, chicken).

(Ali, Toowoomba)

Ali added that it could take even longer due to traffic. Such trips added to product cost (see further below). He noted he would prefer to be able to go to a local supermarket. Instead, he said, they had to go to the supermarket, local food stores, and further afield to find what they required.

Sourcing culturally appropriate food, specifically halal meat, can prove difficult for some families. A few supermarkets were noted for being distrusted in their labelling and participants reported to find the meat ‘tastes different’ to what they were accustomed to.

3.1.3. Food Insecurity and Economic Challenges

Food affordability was an issue for most families in this study. As well as mentioning the additional cost often involved in purchasing halal food, nearly all participants noted that if their budget allowed, they would shop differently and buy fresh healthy food, particularly organically produced food, instead of unhealthy choices.

Many participants commented on the high cost of fresh fruit and vegetables.

I think the food prices in Australia are expensive compared to other countries, especially if you want to eat healthy food, like fresh fruit and vegetables.

(Salwa, Perth)

Many participants restricted individual portion size and hence food intake, both as a health measure but also as an economy measure when the budget was very ‘tight’ and there were other calls upon their income (e.g., electricity bills, private Islamic school fees). This could result in food substitution or restriction, as shown by Salwa:

I usually put two snacks in my children’s lunch boxes but these days it’s hard to afford that, so I just put one type and I just buy the fruit [sufficient only for the] school lunch box, not for weekends and I don’t buy fruit during the school holidays.

Prices varied substantially between locations. For example, a large bunch of fresh coriander (commonly used herb in Arabic cooking) may cost $8 in Sydney but $15 in Wollongong. In rural and remote areas, food prices for fresh foods are far higher than in capital cities or regional areas. The situation is exacerbated in periods of drought. For higher income or smaller families, the impact may be less.

I remember once, Australia had a drought, and the price of fresh vegetables was very expensive, for example, … one kilogram of cucumber was about 8 dollars, for us—a family of two—it was okay.

(Aziza, Wollongong)

While some families reported various obstacles to securing a healthy diet, other families were able to provide a healthy balanced diet every day for all meals due to their high economic status and convenient dwelling location in relation to sources of reasonably priced, religiously appropriate foods. Higher income made quality food easier to purchase.

For me, I find most of the food is affordable, no problem for me with the food prices in Australia. I believe compared to the income people get here, the food prices are affordable on supermarket shelves. For some brands, I find the food price is too high.

(Nama, Sydney)

Low income is a pronounced barrier to access to healthy nutritious food. Even when migrants are highly educated, often their employment may not match their qualifications due to lack of transferability of those qualifications and the language barrier. Their remuneration may reflect the fact that they have had to take a job far below their qualifications to feed their families. Permanent employment can also be difficult to find in a country where casualisation of the workforce has been continuing over many years. Migrants often find themselves able to gain only casual employment and may struggle in their adoptive country for some time.

Nonetheless, some (often with sought-after skills and a greater facility in English) enjoy relatively high incomes and have little problem accessing food in the quantity and of the quality they desire. A few, however, struggle due to assisting relatives abroad (often ageing parents) or repaying debts incurred for their migration.

As well as the physical obstacles (such as location) and economic challenges (such as low income, expenses, and higher cost of food) outlined above, there are other problems associated with a lack of availability and obstacles to utilisation (such as unfamiliar ingredients, tools, and utensils to prepare that type of food, lack of extended family in Australia, and having limited time as working parents).

3.1.4. Food from Our Homeland and Its Unavailability in Australia

There was a frequently expressed desire for greater availability of familiar foods (from migrants’ homeland) in major stores, not just in specialist food stores, which might be difficult to locate or far from the person’s home. As one participant noted:

Ahh to be honest I wish I could go to Coles or Woolworths because the same store is all around Australia. I wish if I could go there, find, and buy traditional Libyan food. Just the main food even. For example, we missed …. Bsisah. We missed that dish a lot, not sure if you heard of it?

(Ahmed, Hobart)

Specific foods sometimes require specific tools for use in meal preparation. These too can be difficult to access in Australia (for example, commercial size seed grinder for domestic use) or can be very expensive if found.

I miss eating Zumeeta. I know how to make it. I have the ingredients, but I cannot make it in my kitchen with my kitchen tools because it requires a big strong seed grinder.

(Eataq, Melbourne)

3.2. Theme 2: Understanding of Food Labels

Some migrants have enough nutrition literacy to facilitate suitable choice of products. However, sometimes they had difficulties in maintaining a nutritious diet due to other barriers, such as stresses of life, sudden demands on their income, and a lack of social support.

Due to the general high education levels of the participants, most were able to read food labels and had little difficulty understanding them. Many Libyan migrants sought specific information from food labels related cultural and religious practice, such as a food’s halal status. Some noted that its guidelines were not well-known among non-Muslims, and this could be a source of confusion. The knowledge of halal status is crucial for consumption of processed and other products by an observant family.

If you can find halal logo, that is great for us, so we can just buy it. But if you don’t have the halal logo, it’s quite difficult because we have to read the ingredients and ask questions and investigate the ingredients, so it’s a long process, even sometimes the answers are not inclusive. If I cannot find the answer, I leave the product. It would be so much easier if the product has the halal logo.

(Abdulsalam, Brisbane)

Ingredients of specific concern included rennet, gelatine, and emulsifiers from animal sources, as well as alcohol, all of which are haram, as explained above. Iman (Wollongong) noted:

I was afraid that I would eat something not halal. I had little knowledge about the products on the shelves… even the bread. I had been told they put gelatine in the bread.

Iman commented that she found the system of numbers on labels very difficult to understand. It was impossible to memorise all the numbers and what they stood for. For her dietary practice, it was very important for her to know whether a product contained rennet or gelatine, for example, while whether it contained a particular dye was unimportant to her. The tiny font size also made reading the labels difficult. Iman was not alone in her difficulty. Most participants commented on the difficulty they encountered trying to read the numbers in such small fonts and in finding the correct number for an ingredient which was unsuited to their cultural or religious requirements. As migrants’ experience and knowledge grew about local as well as imported foodstuffs, their food choices expanded. Iman reported now finding a great variety of acceptable foods, including culturally acceptable foods and couscous she had first thought unavailable in Australia. The source and type of emulsifiers and so forth, presented as numbers, remained difficult to identify easily.

The use of numbers for products rather than words saves space on labels but this can cause confusion in consumers. Some migrants have contacted manufacturers for clarification.

[P] products with emulsifier with 400 numbers I don’t buy them because it means they are from animal sources. I usually email the company to clarify. Some dairy products, if it says [vegetarian] rennet or non-animal source, I buy even if it’s not [stated/labelled] halal. But if it says rennet when saying the source, and I wish to buy it, then I email the company to clarify.

(Adel, Hobart)

Terminology can prove to be a barrier to non-English speaking migrants and to Australian-born English speakers.

The presence of an authorised Halal logo gives the purchaser confidence to buy the product without having to scan through all the ingredients, and many Libyan migrants expressed a desire for it to be more freely used on products. Many of the participants search for this information when shopping for food.

I usually don’t look at sugar and fat, but I do look at the ingredients. For example, when I go to the bakery, I look at the emulsifier [to see] if is halal or if it’s from vegetable or animal. I do look at the numbers. If I am not sure, I ask the customer service [person].

(Soma, Sydney)

Many others, however, are looking for nutrition information, as well as halal status, prior to purchase.

Food labels are very important for me; first because I am a Muslim and I look for the halal logo on the product. The second reason is [that] because I am a dietitian, I always look for healthy food or a healthier option.

(Aziza, Wollongong)

Migrants could also have other concerns, including fat and sugar content, for example, for diabetics.

I have to look at the labels to see if the product has any emulsifiers or rennet and preservatives and then how much fat and sugar the product has. I look at the first 3 ingredients. According to the product, the first 3 ingredients have the greatest concentrations. For example, if I am buying juice, l look to see how much sugar and real fruit it has in it.

(Aziza, Wollongong)

Buyer trust in meat was a particular problem, especially where halal and haram products were sold in the same store.

Sometimes even in a meat store where they have a certificate that says [they sell] halal meat… You will see they sell pork on the other side…Last week I asked them, ‘Why do you guys have a certificate [that] you have halal meat and you [also] sell pork?’ and they said, ‘We do pork on a different day—we clean everything, we do it on different day.’ Still, to me [this is] not right and I am not comfortable to eat that meat.

(Salma, Toowoomba)

However, things have been changing as the Muslim population living in Australia increases (and also due to slaughter of animals for consumption in Muslim countries). Where once halal butchers were rare, now halal meat can be more easily procured.

We usually buy halal food from a specific shop. Before we had only one shop, and we had to drive nearly one hour to get to it here in Wollongong, but now we have many shops who sell halal products, even in the giant supermarkets you can find middle eastern products. I can say we can buy all the halal food here. It’s more available now than 12 years ago when I first came to this country.

(Shahd, Wollongong)

However, the experience is not uniform across Australia. Hobart (in Tasmania) is a relatively small city where most people do not have sufficient knowledge about culturally appropriate food such as halal status.

One day, I went to a big store, not sure if it was Coles or Woolworths, and I asked the staff member there (she was a girl), I asked her about it and she said, ‘What?’!!!! She did not know what that meant, so I said, ‘Halal’, and I started explaining what ‘halal’ means.

(Ahmed, Hobart)

3.3. Theme 3: Strategies for Dealing with Food Insecurity and Food Labelling Difficulties

3.3.1. Physical Obstacles

A few families solve the problem presented by distance to source appropriate meat products by travelling to rural areas where an animal can be slaughtered to halal specifications.

No halal butcher is close to us. Each month my husband goes far away to a farm to get freshly [halal] slaughtered meat.

(Rana, Perth)

Some families would travel together from a regional area where a product was not readily available to a city area so that the cost of travelling could be shared. They also took this opportunity to socialise with others.

We have a halal butcher but we drive to Sydney because it’s much cheaper, same as the fruit and vegetables we buy bulk. We go as a group of families to share the traveling cost and to enjoy eating in fine dining halal restaurants.

(Arwa, Wollongong)

3.3.2. Economic Challenges

Some families were trying with great care to improve their food choices despite their limited income. Many also emphasised that they were seeking different ways to eat a healthier diet as consistently as they could. They were conscientious in trying to have nutritious foods and variety in their diets while ensuring that they could provide enough food at the lowest expense. For instance, in their attempts to deal with food hardship, some participants often purchased frozen fruit and vegetables and nutritious food in bulk when ‘on special’ offers.

When the tomatoes and peaches are on special in boxes, I buy them, even though I know that they are nearly spoilt. I must cook them immediately. I make sauces and give some to relatives.

(Arwa, Wollongong)

Some migrants acknowledged that buying fruit and vegetables ‘on special’ meant that this produce was usually not of optimum quality and did not last long. They bought it to stretch their food budget and meet their families’ food needs. Migrant householders may immediately cook such foods (as above) or freeze them. Alternatively, householders use fresh produce straightaway or juice it. One participant, Amani (Wollongong) said of the fruit and vegetables: ‘I know they have lost most of the nutrients but (I) just feed them [to my family] so that they will not be hungry’. Buying in bulk, thus, brings other challenges.

I usually buy fruit and vegetables in bulk if they are on special or buy at farmers’ markets because the products are cheap with good value. … to finish it before gets spoilt, I must cook the same dish repeatedly.

(Ayman, Sydney)

Different families adopted different strategies to counteract low income. Some families maintained a repetitive diet as a conscious strategy when trying to stretch their income resources over the month (a strategy facilitated by bulk buying). Others have adopted a different diet involving inexpensive products such as dried noodles and tinned fish.

Libyan food takes a long time and also [has] a lot of ingredients involved in the food, maybe… this is the thing, … here we eat mostly fast food or whatever we have, like instant noodles or tuna and salad. [It] may be [that] it is easier to cook, [we] lack time, or ingredients to make a proper meal.

(Eataq, Melbourne)

Often families go together to the farmers’ or Sunday markets to buy fresh food in bulk. This allows them to access produce at a lower price and also share produce with family and friends. This is an effective means of reducing outlays and reinforces familial and cultural bonds.

Others tried to reduce the impact of high fruit and vegetable costs by adopting other strategies, such as ‘eating seasonal produce as the prices are not as high’ (Arwa, Wollongong). The same interviewee mentioned that the consumption of food in season was a traditional (not religious) practice in her homeland.

While parents expressed their desire to consistently provide nutritious meals for their children, nearly half reported restricting school lunch box snacks to ensure their children had enough to eat throughout the month. While some restriction of ‘snacks’ is laudable (as they can be energy dense, fat and sugar rich foods), undue restriction of protein, and elimination of vegetable and fruit as ‘snacks’ due to high cost would not be a healthy outcome and parents seek to avoid it.

Participants would also travel from store to store to ensure that they accessed the best bargains and capitalised on sales. While this took quite a long time, participants did it to ensure they had sufficient good food at the lowest possible price, thus making their budget stretch further. Few relied on community charity hampers, preferring to adopt community buying, cooking in bulk, eating seasonally, and travelling widely from store to store (local and supermarket) to obtain the products required.

3.3.3. Food from Our Homeland and Its Unavailability in Australia

Attempting to access familiar foods can bring unintended consequences when relatives or friends (or returning or new migrants) try to secure access to favourite foods and spices for migrants in Australia by bringing ingredients unable to be sourced domestically into the country.

So, what we do with that [is] if a family [is] coming from holiday in Libya, they try to bring from overseas a large amount of particular food ingredients that we missed and enjoy eating. If it was permitted and passed by the Australian Border Force, then we gather and share it. As you know any food item brought into Australia needs to be declared. So, … not everything we wish to bring can be acceptable. We have many stories of people bringing food [in] that ended up with [that food] confiscated.

(Nama, Sydney)

3.3.4. Food Labelling

Various strategies were adopted to address difficulties posed by Australian food labelling practices. Some participants contacted companies directly. Soma (Sydney) found that if she was very keen to buy a product and contacted the company to check with them, the process was ‘fairly easy [as] they get back to you in a matter of hours’. Others, however, found it difficult, saying that ‘it’s a long story for me to explain and ask the company’ (Arwa, Wollongong). There are other problems caused by labels that lack clarity and are difficult to understand.

I just ignore that product [one with unclear labelling] and find something else, but this is very hard when my children hold such products like cakes and ice cream and I have to tell them ‘no’, not because of money shortage but do due the ambiguous food labels.

(Arwa, Wollongong)

Others checked products online to determine whether they were halal, and to find out what the numbers on the labels meant. This offered advantages.

I prefer to check online before I go to buy the ingredients, especially the new products, to save my time and also to not disturb the other shoppers because I feel I annoy them when I stand for a long time in front of the shelves. Also, sometimes I call the company in the shop to check the source of the product but more often I ring from home before I go to the shops.

(Shahd, Wollongong)

Some participants chose to shop only at local Arabic shops to ensure that all products purchased were halal.

I feel safer to buy from Arab food stores. I mainly buy the [prepackaged] juice and the chips and crackers for the kids from the Arabic shop because at least it [product information] is written in Arabic so I have no doubt that it is halal. I know it is low quality but at least it has no alcohol or gelatine in it. I had experience of buying products from supermarkets and then having to throw food out when I discovered it was not halal.

(Anas, Melbourne)

Participants tended to restrict their shopping to local Arabic stores where product composition or origin could easily be confirmed by looking at the label and talking with the owner if the participants had lower levels of English comprehension. It also prevented unnecessary waste that made participants, such as Anas, feel guilty.

Faced with an unfamiliar vocabulary, many Libyan migrants demonstrated a determination to understand the labels.

Sometimes they use difficult terminology on the food labels but we try to research it and find what that means, but we are quite familiar with that now. On average, once a month I need to research a word from the food label that I don’t know.

(Soma, Sydney)

Many participants also provided suggestions on improving the current system so that it would better meet their needs for clear and easy to read labelling. The priorities included the adoption of an appropriate logo and increased font size.

Most expressed the belief that label comprehension could be increased by it being written in a clearer way such as, using the name and source of the ingredients instead of numbers and symbols. Moreover, it could be enhanced by a greater use of the halal logo where food qualified for such labelling.

It will save a lot of time and that would make me feel very happy, not feel guilty and [it would be] easy to find my stuff quickly from the supermarket rather than to buy only some stuff from Coles, and maybe [then] need to drive 20 kms away to the halal store to buy halal meat. So, if we can find that [logo] in Woolworths or Coles, it will be convenient for us. That will be definitely better and will save us a lot of time.

(Ahmed, Hobart)

As can be seen above, migrants adopted strategies to streamline their shopping experience when seeking culturally appropriate foods. Over time, strategies change. Some of the participants (e.g., Juli of Sydney) observed that during their first years, they looked at the ingredient list of the product online before they went to the shop to save shopping time and because they felt that standing in front of the products for a long time might disturb other customers. Some migrants also learnt the specific numbers for haram products to be able to avoid them. Over time, migrants also become familiar with where desired foods are available and combine with neighbours and friends to access them in a cost-effective manner.

4. Discussion

Situated within a food and nutrition security framework, this paper provided insight into the food security experience among Libyan migrants in Australia. Many participants believe food security is more than having sufficient nutrition available at an affordable price and of a suitable quality for consumption, as well as not suffering from severe hunger [

1]. This involved having sufficient financial resources so food is readily able to be purchased [

46]. For others, it means having a balanced diet, with sufficient nutrients to sustain a healthy life. Some respondents confused the concepts of food safety and food security. For them, food security means food safety, e.g., food free from contaminants. Food security has been traditionally closely linked to food safety. This concern has been, and continues to be, addressed via legislation around the globe (e.g., in the UK from the 1800s, and later within the European Union, whose legislation usually constitutes a blueprint for many developing countries) [

47,

48]. Among matters subject to law are rules for animal slaughter and food importation, both of which were touched upon by interviewees in their approaches to meeting their food needs. Education related to such matters needs to be undertaken among migrants to ensure both food needs and legislative requirements are met for these regulations may differ from those to which they were previously subject.

For many respondents, another consideration looms large. As interviewees are Muslim migrants, religious dietary guidelines make certain foods religiously permissible or lawful (

halal) and others unlawful or not religiously permissible (

haram) [

49]. A lack of such foods (or their greater expense) can lead to a compromised diet and food insecurity [

2]. Interview data revealed the need for increased food security among Libyan migrants who experienced difficulty in securing adequate quantities of acceptable food of sufficient quality to meet their requirements.

The lack of

halal food as well as certain familiar cultural foods were the main concerns among the participants. The location of

halal food stores, their distance from interviewees’ homes, and ease, or otherwise, of access to such stores, could form an obstacle to accessing such foods [

2,

50]. This could result in purchasing foods from convenience stores that tend to lack healthier options [

51,

52,

53].

Food purchasers from families living in major cities such as Melbourne (Vic) and Sydney (NSW) had no difficulty accessing culturally and religiously suitable foods. Interviewees from cities with less cultural diversity, such as Perth (WA), and smaller cities and towns, such as Wollongong (NSW) and Toowoomba (Qld), encountered varying degrees of difficulty in accessing suitable foodstuffs. Those from smaller towns or regional or rural locations noted that they travelled some distance and had to shop from both supermarkets and local food stores to access culturally suitable foodstuffs. Migrants in major cities on the Australian mainland were able to satisfy their food requirements fairly easily, from supermarkets rather than specifically

halal produce suppliers, unlike Tasmanian migrants who experienced a lack of cultural food products in supermarkets, and had to shop from various other stores (such as Asian food stores) to satisfy certain cultural food requirements [

13]. This is possibly due to a lower concentration of CALD (particularly MENA) migrants in Tasmania [

25].

There were other issues related to availability and the cost of food, particularly healthy, culturally familiar, and religiously acceptable food [

10]. The cost of such foods was generally far higher in regional areas than in Australian cities [

13,

54]. Thus, location and economic factors intersect for purchasers [

55,

56]. However, there were notable deviations in the perceived importance of different dimensions for different families. Cultural suitability of foods was in some families prioritised over food quality. Religious acceptability was often the most important aspect to be considered in some instances (e.g., meat). Life stresses and lack of social support further complicated migrants’ ability to access culturally and religiously appropriate food. For some migrants, while they accessed

halal foodstuffs, they still found accessing traditional spices and other materials difficult. Others lacked appropriate equipment as it was rarely imported. A few studies echoed our findings on the role of cultural background, the location of residence, and its relative isolation. The study by Yeoh [

54] of a migrant population in Tasmania found migrants adapted to the new food culture by using different acculturation strategies, such as accessing food from various places (including interstate capital cities and overseas), using freezing as a storage method and modifying food preparation methods [

54]. The study concluded that factors affecting migrants’ food security were strongly shaped by migrants’ socio-demographic background [

54].

Income is a distinct barrier to food security among migrants [

33,

54] and general population subgroups [

57]. Interviewees in our study adopted various approaches to try and overcome this barrier. Means included freezing bulk purchases of fruit and/or vegetables or juicing them, as well as sharing transport to reach major centres or rural areas where bulk product and suitable foods could be accessed. Those families in higher income brackets were far less likely to encounter such difficulties or have to adopt such strategies. The fundamental reality for most Libyan families in Australia is that expenses often outstrip income. Families often compromise on this ‘elastic’ basic need—food—when other financial requirements (e.g., a power bill, or unavoidable medical treatment) trigger a sudden increase in expenditure, or when a sudden loss of income brings hardship. Therefore, some of them work very conscientiously to formulate and manage their monthly budgets and allocate appropriate funds toward their rent, utilities, and transportation, as well as saving to fulfil expected obligations (e.g., support an aged relative) and meet urgent costs in emergencies (e.g., medical or dental). Others, however, experience great difficulty achieving such goals [

58]. A 2006 study by Renzaho and Burns found Sub-Saharan African migrants in Victoria experienced similar difficulties to migrants in our study. They experienced difficulty locating their traditional foods, particularly vegetables, unprocessed maize meal, camel milk, and maize [

58]. In common with Libyan migrants, they adapted recipes, began to access unfamiliar vegetables, fruit, and other foodstuffs, including processed foods. A 2014 qualitative study by Yeoh et al. of a migrant population in Tasmania found, as our study did, that a migrant’s cultural background strongly influences their food security [

54].

In another 2014 a study by Yeoh et al., length of stay in Tasmania and region of origin were significantly associated with the migrant experience of food security [

13]. Length of stay and region of origin were also factors mentioned in our study as interviewees noted that they became more familiar with local products over time, and this affected their food purchases and food access. While over half of the Tasmanian participants in this study indicated that food costs were high in Tasmania (especially for culturally specific food), a high proportion of them were satisfied with the cost of food nevertheless. Again, in common with our study, the themes that emerged included food availability, accessibility, and affordability, while concerns included a lack of access to cultural foods or difficulty accessing them (e.g., having to travel long distances to obtain them) [

13].

It was noted that while many migrants were highly educated, they were still food insecure [

33]. They were highly literate but struggled with some aspects of labelling. They had no difficulty reading the list of ingredients; however, they were unable to differentiate between which products were suitable for them and which products were not. The complexity of the food label’s presentation was an issue that caused concern among the general population, and it has been associated with food insecurity [

59,

60]. Additionally, some migrants need to understand the food labels to recognise foods that are culturally or religiously appropriate for them. A 2010 paper on migrants to Australia from the Horn of Africa and their understanding of their new food environment found that nutrition messages are too complex and impede comprehension, especially among the less literate [

61]. This has the potential to affect dietary decisions and subsequent health outcomes negatively. Our study found that while socioeconomic aspects influenced consumption, the potential for nutritional food labelling to assist healthy food choices was undermined by difficulties in comprehension, presented by the complexity and formatting of nutrition-related labelling.

A 2012 US study (conducted among migrants from the former Soviet Union (FSU)) found that those surveyed experienced difficulty using food labelling [

62]. Research among a similar cohort in Israel found that socioeconomic factors were of greater importance than nutritional labelling in determining food consumption. The FSU migrants reported less than the native Israeli population on the need for nutritional labelling and did not consult such labels when purchasing food. Only age and migration correlated to healthy food consumption. Unlike our study, religious observance and education did not affect their food choices [

63]. Our study also found that problems persisted regarding labelling among some participants despite high education levels. The specialised language and interpretative skills could likewise make such labels less easily comprehensible even to native English speakers, especially to those with lower educational attainment.

Strengths and Limitations

This study is the first qualitative study on the food security among Libyan migrants and comprises an in-depth exploration of factors involved in their food security experience. It also explores the relationship between food labelling and food insecurity in that population. Its strengths include its involvement of a researcher from that population who is fluent in both English and Arabic, which meant that language was not an issue. The current study, with its use of a familiar ‘mother language’ for interviewees, maximises participation and accuracy of data collection, while the use of translation makes the information gathered accessible to a broad range of researchers and policy makers.

There are several limitations with this study. It was initially expected that the number of interview participants would be a minimum of 40. However, by the receipt of final communication there were only 27 participants. Nevertheless, the saturation point was reached at 20 interviews, although the remaining 7 were also analysed but no further themes were constructed. This confirmed the coverage of the material despite fewer than anticipated respondents. It should be noted that the voluntary nature of this sampling strategy might have resulted in a sample population that had a higher desire to respond fully to the interview questions, thus providing substantial data. As a convenience sample, the generalisability of the data may be limited because of difficulties that exist in generalising to larger populations. Additionally, the characteristics of the sample might not be typical of the other migrant populations. Therefore, it is suggested that researchers might consider undertaking similar research among different migrant groups, assessing their food security experience. A comparative study would enable researchers to determine whether the factors involved are similar or differ.