Abstract

Mindfulness has rapidly become a significant subject area in many disciplines. Most of the work on mindfulness has focused on the perspective of health and healthcare professionals, but relatively less research is focused on the organizational outcomes at the workplace. This review presents a theoretical and practical trajectory of mindfulness by sequential integration of recent fragmented scholarly work on mindfulness at the workplace. The review showcases that most contemporary practical challenges in organizations, such as anxiety, stress, depression, creativity, motivation, leadership, relationships, teamwork, burnout, engagement, performance, well-being, and physical and psychological health, could be addressed successfully with the budding concept of mindfulness. The causative processes due to higher mindfulness that generate positive cognitive, emotional, physiological, and behavioral outcomes include focused attention, present moment awareness, non-judgmental acceptance, self-regulatory functions, lower mind wandering, lower habit automaticity, and self-determination. Employee mindfulness could be developed through various mindfulness interventions in order to improve different organizational requirements, such as psychological capital, emotional intelligence, prosocial behavior, in-role and extra-role performance, financial and economic performance, green performance, and well-being. Accordingly, this review would be beneficial to inspire academia and practitioners on the transformative potential of mindfulness in organizations for higher performance, well-being, and sustainability. Future research opportunities and directions to be addressed are also discussed.

1. Introduction

In recent times, an intensified inquisitiveness has grown among scientists of many disciplines to delve into the mindfulness concept entrenched 2500 years ago in Buddhist teachings [1,2,3]. Practice and research on mindfulness increased tremendously in the last decade [4], and more than 90% of scientific work on mindfulness has been carried from 2010 onwards [3]. Notably, the recent upswing of attention on mindfulness was due to the seminal work of Jon Kabat-Zinn, the pioneer who introduced this tool to Western secular culture [5]. By this time, mindfulness meditation has integrated, to a certain extent, into medicine and science mainstreams, and has become a hot topic in cognitive science and affective neuroscience [6].

A recent evidence map, created through summarizing the systematic reviews on mindfulness interventions, revealed that most studies had been conducted to evaluate the health benefits of mindfulness. The majority of tasks in workplace mindfulness interventions are targeted at healthcare professionals [7]. Hence, relatively little effort has been made by organizational scientists to evaluate the other benefits of mindfulness in the workplace compared to the health benefits. Nevertheless, recent research findings demonstrated a wide array of positive outcomes for individuals, teams, and organizational culture due to mindfulness and mindfulness interventions. Some leading outcomes include performance, well-being, citizenship behavior, pro-social behavior, workplace spirituality, human health, human rights, and social justice. In tandem with the findings, the body of knowledge on mindfulness is rapidly expanding, and the attention of scientists from diverse fields, such as healthcare, business communities, education, religion, and sports, is drawn to the positive effects of the mindfulness investigations [8,9,10,11,12].

The law of impermanence has no exception to any workplace, as the working environment continuously changes. Although an employee has a great deal of power and influence, intrinsic limits exist either in changing things or objecting to changes. Job stress, insecurity, frustration, and failure are common phenomena in almost all employment [1]. Furthermore, prior research has proved that high work stress due to psychological job demands, low work social support, work decision latitude, and physical work demands cause major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, even among employees without a previous history of such disorders. [13]. Excessive role stress is caused by unawareness, partial seeing, or misperception. Nevertheless, the amount of psychological stress that an employee undergoes varies on how an individual perceives things [1].

Employees who work mindfully in any context cope efficiently with work stressors by setting up all inner resources to endure problems (emotional turmoil) at work [1]. Nevertheless, empirical evaluation on the effect of mindfulness at the workplace is scarce [14,15]. Scientists proposed mindfulness as a root construct in management science [8,10,16]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined health “as a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. Hence, with the perspective of employee health and organizational management, policymakers and academics have tremendous responsibilities on their shoulders to prepare employees to cope with perceived work stress, minimize stress at work, and avoid the incidence of developing depression and anxiety to a clinically significant stage. Therefore, the study of the mindfulness concept concerning organizational management is pivotally critical.

Phan et al. [17] suggested that people’s state of functioning could be optimized by mindfulness. Mindfulness meditation could be used as an optimizing agent to achieve optimal best practice in the tenets of the optimization theory in positive psychology. Moreover, scholars have recently attempted to consider the positive gains of mindfulness in organizations, and demonstrated that mindfulness enhances everything, including resilience, social relationships performance, and well-being. Mindfulness research in neurobiology proves that mindfulness-related changes in brain structures and activities affect increased awareness, careful affective and physiological regulation, and positive mental experiences. [8,10].

Hyland et al. [5] noted that many front-line organizations, such as Google, General Mills, and Aetna, embraced training programs on mindfulness within their workforce, intending to improve employee well-being and efficiency. According to Chade-Meng Tan, the founder of Google’s initiative on mindfulness training, “Search Inside Yourself”, attention training develops the ability to maintain a calm and clear mind even at a high emotional demand, which is the foundation for emotional skills, such as intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligence, resulting in numerous benefits, including stress reduction [18]. Besides, mindfulness meditation became a billion-dollar trade in 2016, representing 22% of Fortune 500 firms that already implemented mindfulness programs at work [19]. As a milestone in the mindfulness trajectory, the British House of Parliament took nationwide initiatives to implement mindfulness interventions for sectors mainly covering healthcare, the workplace, education, and the criminal justice system after eight hearings. The initiatives help enrich people’s mental capital to enhance productivity and creativity, leading to a better economy in the United Kingdom [20,21].

Scholars also noted an ongoing controversy among organizational scientists about implementing mindfulness interventions in the corporate sector, notwithstanding the trends mentioned above in various fields [5]. The world business community that utilizes modern concepts and technologies would become naturally reluctant to apply spiritual concepts originated from a religion that is neither followed by the majority of the world population, nor commonly practiced in the developed world. Hence, cross-cultural, or interdisciplinary studies on this tool would provide comprehensive long-lasting solutions to burning issues in organizational science.

At this juncture, a review with coherent integration of fragmented findings on this concept is crucial to understand such a phenomenon widely used in mainstream management. Moreover, a rationally comprehensible impression about the concept and the benefits, such as increased productivity and well-being of the employees, by applying the concept, should be available to invest in a concept such as mindfulness empirically or practically. On this backdrop, the researchers of the current study observed that although reviews on the mindfulness concept are available in the literature, no comprehensive integrative review covers the recent findings progress, specifically during the last five years, and the effects and mechanisms in organizational management. Accordingly, this review attempts to fulfill the following three key objectives: 1. ascertain current research progress and implications of mindfulness research on the workplace; 2. characterize the causative processes of higher mindfulness that generate positive outcomes; 3. communicate a future research outline.

The narrative review approach has a great potential in identifying research progress over time, detecting theoretical perspectives, and creating future research agenda [22]. In order to accomplish the above objectives with a greater understanding of the wide range of impact of mindfulness on the workplace functions, well-being, and the health of employees and overall sustainability comprehensively, the narrative approach was adopted in this study. The relevant articles for the study were identified, particularly in the Clarivate Analytics’ Web of Science in view of producing a quality article pool. The search string was (mindfulness and ((organi* or workplace Management) or (organi* or workplace performance) or (organi* or workplace well*))), and tracking new publication email alerts were activated to get the latest publications after the initial search. The first search of the literature yielded 1838 results. In order to identify additional good quality materials for a thorough understanding of the concept, and to prevent erroneous conclusions about gaps in the literature, we employed reference list scanning, citation tracking, and further searching in Scopus and Google Scholar databases where appropriate. The publications on mindfulness, mindfulness meditation, and other mindfulness-based training programmes related to the workplace covering public and private organizations were included in the current review. Studies on mindfulness intervention types such as long-term, short-term, face-to-face, and online are included. Materials published in English were considered for the review. Although more emphasis was placed on the last five years’ publications, some of the publications beyond this period that were crucial for scientifically sound narrative synthesis were also included. Publications solely focused on the benefits of mindfulness on clinical medicine, neurobiological and physiological outcomes, sports, religion, and student education were excluded. In addition to that, research involving practices other than mindfulness meditation, such as yoga and relaxation, were also excluded. Accordingly, this review presents a broad overview of up-to-date knowledge about the mindfulness phenomena, and contributes profoundly to the theory and corporate practice by exposing the great potential of the concept concerning organizational and salutary outcomes, and avenues for this nascent field’s future research and practice.

The structure of the remaining sections of the paper is as follows. Definitions of mindfulness, and scientific understanding of the attention and causative process of mindfulness are discussed in Section 1, followed by Section 2, which examines the evidence for mindfulness as a construct in organizational management. Section 3 discusses the theoretical and practical contributions of the review, and the future research directives on mindfulness. Finally, the conclusions of the study are presented in Section 4.

1.1. Definitions of Mindfulness

Scholars have several well-accepted definitions of mindfulness. The foremost definitions in the literature are presented in Table 1 to understand the particular conceptual domain. A significant concern about the concept is the non-existence of common accord among scientists on the definition of mindfulness, which could be a significant drawback for the field’s growth.

Table 1.

Definitions of mindfulness.

Building on the conceptual coverage of the definitions by Kabat-Zinn. [26,28] and Bishop et al. [27] which encapsulated the Buddhist doctrine of mindfulness [29], Feldman et al. [30] identified four dimensions in mindfulness: (1) the ability to regulate attention; (2) an orientation to present or immediate experience; (3) awareness of experience; and (4) an attitude of acceptance or non-judgment toward experience. However, no common consensus is observed among scientists on the definition and operationalizations [31]. Therefore, a more inclusive interdisciplinary alliance of scientists in the relevant fields, including Buddhist philosophers, is suggested to present a new, widely accepted definition, and the concept should be operationalized for work contexts.

The capacity of naturally occurring mindfulness that varies between persons is identified as the trait or the dispositional mindfulness. The mindfulness level that changes moment to moment within a person is called state mindfulness. Mindfulness meditation interventions enhance state and trait mindfulness [25,32,33]. Kabat-Zinn. [34] introduced mindfulness meditation as possibly the “most basic, the most powerful and the most universal” among the various meditative wisdom practices existing in the world. He defined meditation as “systematic and intentional cultivation of mindful presence, and through it, of wisdom, compassion, and other qualities of mind and heart conducive to breaking free from the fetters of our own persistent blindness and delusions”. He also accentuated that mindfulness meditation is the most required practice in the present world context for the well-being and healing process of human beings and the world.

1.2. Scientific Understanding of the Attention and Causative Process of Mindfulness

First and foremost, the basics of mindfulness’ influence on the attentional process have to be identified scientifically to proceed in the course of understanding mindfulness. The cognitive-behavioral process and behavioral regulation are influenced by the information received from direct, vicarious, and symbolic sources [35]. Attention is the prime feature of mindfulness, where three facets are identified in relation to mindfulness, namely attention stability, attention control, and attention efficiency. Attention stability reduces mind wandering, and increases present moment focus with sustained attention. Attention is paid appropriately to undermine habitual attention, and to distract information in attention control. Attentional efficiency is achieved by allocating greater attentional resources to process the appropriate targets, and a few attentional resources to process unnecessary targets. This attentional process results in cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and physiological outcomes [8,36]. As a result of retarded habitual behavior, employee negligence, and carelessness, higher productivity and work performance are achieved [37]. Therefore, mindfulness reduces unawareness, partial seeing, or misperception, leading to the above positive outcomes.

Individuals with high mindfulness tend to use proactive and reactive cognitive control with a more balanced approach than low mindful individuals who mainly rely on proactive control. Therefore, more mindful individuals depict higher flexibility, as both essential processing modes are functioning. In addition, individuals exhibit greater flexible performance due to increased non-judgmental present moment focus [38]. The automaticity of habit is independent from attention [39]. Prior literature proposed that mindfulness significantly impacts self-regulation [25,36,40] by reducing automaticity, and by better prediction and higher congruency between values and actions, leading to a self-determined behavior that is along the lines of the self-determination theory [10,41,42]. Additionally, neurological evidence indicated the efficiency in improving the self-regulation process because of mindfulness interventions [43].

The benefits of a balanced approach in proactive and reactive behavior should be evaluated by scholars in light of mindfulness findings, although proactive work behavior is appreciated for certain situations in management science. There are instances where sudden reactive decisions are needed to be made in complex organizational behavior. Hence, the non-judgmental present moment awareness developed through mindfulness intervention is likely crucial for a more balanced approach of proactive and reactive cognitive control in self-regulation. Accordingly, mindful individuals may not work merely on their previous experience. They work with less habit automaticity and less mind-wandering than their less mindful counterparts due to improved non-judgmental present moment awareness. Therefore, they understand needs, values, and interests with clear comprehension, and act with self-determination (intrinsic regulation).

Various attentional capacity improvement interventions have been introduced in order to foster mindfulness. The majority of the interventions are almost similar to mindfulness intervention techniques that can be implemented in organizational contexts, namely a mindfulness-based stress reduction program (MBSR) [44], and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) [45]. In addition to those programs, different modified versions of mindfulness training programs are designed and implemented using most characteristics of the two programs mentioned above [42]. Nevertheless, the majority followed MBSR [46]. For example, mindfulness-based resilience training (MBRT) was developed based on MBSR [47]. Other interventions include mindfulness meditation, loving-kindness meditation [33], and JW2016 brief mindfulness meditation [48].

2. Mindfulness as a Construct in Organizational Management

Previous studies have pinpointed two primary factors common among working adults: psychological distress, and mental health problems [49]. In most cases, employees are unaware that psychological distress may lead to mental health problems, and these conditions are left unattended [50]. Consequently, the condition may lead to detrimental repercussions, such as reduced organizational productivity, absenteeism, and an enhanced health budget for the organization [51]. In his meta-analysis, Virgili [52] highlighted that mindfulness training has been shown to play a more prominent role in this scenario, and reduces psychological distress among working adults.

Short-term mindfulness training programs also improve mindfulness [53], emotional memory, and emotional stability; reduce emotional intensity, negative emotional attention bias [48,54], momentary stress, overall perceived stress at work [55], and work-related stress; and improve self-care and work-life balance [56,57]. Recent meta-analyses reveal that mindfulness training programs were beneficial in lowering anxiety, depression, and stress [43,58], and improving psychological well-being [59], and the beneficial effect persists even after six months of the intervention [60]. Individuals with greater mindfulness can predominantly mitigate stress, leading to depleted dysphoric mood levels through lower state rumination affect [61].

Mindfulness is expected to play a significant role in places where high mental status is fundamental in the job nature, such as in error-intolerant, complex, and dynamic work setups. A study conducted among airline pilots of China Southern Airlines Ltd., where safety operation behaviors are of the utmost importance, revealed that mindfulness has a direct negative link with the pilots’ anxiety, and mindfulness affects anxiety through the influence of employee burnout [62]. Furthermore, other studies undertaken in Chinese nuclear power plants demonstrated that mindfulness is crucial for employees’ task and safety performance, especially among those responsible for high-complexity tasks. [63,64].

Mindfulness can be understood as a discipline of consciousness from a behavioral science perspective [65], and positively associates with self-regulation [10]. In consideration of human agency in social cognitive theory, self-efficacy results in the motivational process and self-regulation of people’s emotions and thoughts [66,67]. Thereby, the ability of self-regulation and reflective self-consciousness may enhance goal-directed behavior and employee engagement [68]. Focus and attention are psychological resources that assist people in dealing actively and efficiently with tasks. Those with high intrinsic motivation can cope with work stress by using available resources [69]. Mindfulness improves the attentional process, and moderates the association between organizational stress and job satisfaction. Therefore, mindfulness acts as a mitigator for employee dissatisfaction in an environment with high work stress by enhancing the focus on job demands, optimum use of job resources, and developing an emotional state of alleviated reactions (lower emotional reactivity) to stress [70], primarily by the non-judgmental facet of mindfulness [71].

Ryan and Deci [41] considered mindfulness as a vital phenomenon in triggering need satisfaction and eudaimonia. According to their self-determination theory, awareness is a primary factor to identify the reality of oneself, and the social and physical environment. Therefore, they argued that competence and mindfulness are imperative components leading to intrinsic motivation. Similarly, Brown et al. [72] unearthed the importance of mindfulness for episodic memory and motivation empirically. Hence, mindfulness is proposed to enhance the employee motivational process and satisfaction that is important for a healthier and productive workforce.

Mindfulness is also essential for somatic learning, where the coexistence of integrative mind and body attunement plays a significant role in management learning, the managing process, and somatic work [73]. Cacioppe [74] argued that mindfulness and flow foster organizational learning, particularly in learning organizations. Therefore, self-perceived competencies may be enhanced. Additionally, mindfulness increases psychological need satisfaction, job satisfaction, task performance, and organizational citizenship behavior, and reduces emotional exhaustion in employees [75].

According to a meta-analysis by Miao et al. [76], mindfulness has a significant positive relationship with emotional intelligence. Concurrently, the analysis found that age has a significant moderation effect on this particular relationship. The relationship was robust for older subjects. Moreover, mindfulness could play a critical role in alleviating females’ low performance in an environment with sexist behaviors [77]. Therefore, mindfulness helps to maintain sound mental status among elderly and female employees.

Scholarly work on the antecedents of mindfulness is limited because scientists recognized this concept as a comparatively stable trait, and relatively fewer empirical attempts exist on mindfulness in organizational science. However, the organizational environment is suggested to influence the employees’ mindfulness. One of the dimensions of mindfulness is employee awareness, which is positively affected by organizational support, such as supervisor support, and negatively affected by organizational constraints and task routineness. Besides, organizational constraints and task routineness positively correlate with absent-mindedness [75]. The changing quantitative and emotional demands at work and home affect the awareness and acceptance facets of mindfulness differently. Therefore, in addition to providing mindfulness training to improve mindfulness, crafting a suitable environment to facilitate mindful behavior is also essential in organizations [78]. Accordingly, the state mindfulness of employees is surmised to vary with the organizational environmental factors, and must be considered to maintain a constant level of mindfulness across various contextual domains.

Scholars summarized the enormous potential of meditation in creativity, intelligence, intelligence quotient (IQ), problem-solving ability, self-actualization, self-identity, self-esteem, wisdom, empathy, perception of others, interpersonal relationships, altruism, work performance, work satisfaction, reduced stress hormone production, neuroticism, depression, sensitivity to criticism, impulsiveness, anxiety, faster recovery from stress, and turnover propensity [79]. In general, scholars provide outpouring support that mindfulness training programs can be undertaken in the organizational context based on recently developed theoretical backups to improve performance and employee well-being. Therefore, researchers strongly encourage implementing mindfulness interventions, and incorporating mindfulness measurements for recruitment and promotional tools, specifically for stressful jobs [3,80].

In light of previous developments in diverse disciplines, the following sections broadly investigate the effectiveness of mindfulness and mindfulness meditation interventions for positive psychological outcomes concerning the core management functions, such as leadership, relationships, teamwork, employee engagement, work performance, and employee well-being.

2.1. Mindfulness on Leadership and Relationships

Leadership is a complicated and critical aspect of organizational success and the well-being of both leaders and followers [81,82,83]. Despite the wealth of literature available in the leadership field, scholars have surprisingly paid less attention to investigate the awareness quality and leaders’ attention. Leaders should identify their subordinates’ motives, expectations, and goals beforehand to manipulate their behavior [41]. Employees typically sense whether the leader focuses on the present moment physically and mentally or vice versa. Mindful leaders have the quality of present focus. Therefore, employees respect their leaders, and tend to develop a better relationship with the supervisor [15].

A systematic review by Donaldson-Feilder et al. [84] identified that mindfulness interventions improve a leader’s leadership capabilities, resilience, and well-being. Mindful leaders practice inter-personally fair behaviors with higher leader–member exchange quality. Such leaders positively affect employee psychological need satisfaction, performance (both in-role and extra-role), job satisfaction, and work-life balance, while negatively affecting employee emotional exhaustion and stress [15,85]. Moreover, mindful leaders display emotionally regulated behavior due to non-judgmental social observations of things happening around them. These leaders consider the needs, concerns, and values in making decisions. This behavior heightens their trustworthiness, and they easily influence their employees’ behavior, as employees trust their leader, feel safe, empathize, and are prone to have a better relationship with the leader [81].

Additionally, mindful leaders are also aware of their problem-solving and decision-making abilities, and they improve these dimensions by using their knowledge and skills. Therefore, followers identify that their leader is competent, which reduces their perceived uncertainty, and causes them to perform well. The leaders’ self-awareness governs self-regulation of emotions under deferent contexts, and depicts consistent behavior with predictable principles across all circumstances. This leadership integrity will influence the organization’s value congruence by aligning followers’ principles with the leaders’ principles, and by employees considering the leader as a role model [81].

Leaders’ mindful awareness and non-reactive stance concerning the employees’ needs improve their supportive behavior. Mindfulness forestalls leaders’ habitual judgments, and executes adaptive and flexible reactions, leading to work improvements. Owing to improved openness to experience due to mindfulness, the leader behaves as a role model, and stimulates the employees’ intellectual behavior. Therefore, leaders’ mindfulness positively influences leaders’ transformational leadership behavior, enhancing employee job satisfaction, and reducing employees’ psychosomatic complaints. Transformational leadership acts as the modus operandi in the association between leader mindfulness and subordinate well-being [86].

In addition, psychological need satisfaction (competence, relatedness, and autonomy) mediates the relationship between mindfulness and transformational leadership. Neuroticism is a boundary condition in the mediation effect of relatedness need satisfaction in the said association [87]. Similarly, scientists revealed that leaders with greater mindfulness build authentic leadership behaviors with their subordinates, and gain greater adaptability, innovation, resiliency, and improved engagement [88]. Thus, evaluating the trait mindfulness of job applicants for leadership positions is suggested [89].

Individuals with a high level of mindfulness improve negotiation effectiveness by using qualities such as building trust, concentrating on actions and appropriate language, flexible outcomes, and maintaining order in their minds [90]. Further, mindfulness training develops speech fluency and voice feedback [91]. Previous studies demonstrated that mindfulness improves listening skills [92], agreeableness [54], decisiveness, creativity [93], research and development intensity [94], moral reasoning capacity, ethical decision-making [11,95], unbiased decision-making [96], decision-making competence [97], and social cognition realms, such as greater empathy, higher theory of mind, higher emotional recognition, and lessens hostile attributional style or bias [98], and interpersonal conflicts [99].

Mindfulness may enhance the positive leadership qualities while reducing the negative leadership qualities of leaders. Therefore, leaders’ mindfulness plays a critical role in motivating and getting the maximum output from subordinates. Effective negotiations, improved appropriate decision making, well-being, and prosocial behaviors due to mindfulness make a conducive environment for higher performance. The relationships within the internal and external organizational environment may be more potent when employees are high in mindfulness. Those strong relationships are critical for employees’ minds to be healthy and successful at work in the highly complex, competitive, and turbulent contemporary organizational environment.

Team Mindfulness

Although team-level relationships and functions are decisive for the team and organization’s success, scholars have made minimal effort to understand the collective measure of the mindfulness construct relational process [8]. In order to address the previously unaccounted phenomenon, Yu and Zellmer-Bruhn. [100] conceptualized and defined team mindfulness as “a shared belief among team members that team interactions are characterized by awareness and attention to present events, and by experiential, non-judgmental processing of within-team experiences.” Researchers have proposed that team members’ mindfulness can be used to curb false consensus (which creates a cognitive bias within a team setting) by interfering with five critical team processes, namely open-mindedness, empowerment, conflict management, participation and value, and ambiguity tolerance. Concordantly, elevated team mindfulness may enhance team decision processes that typically adopt a routinized form of decision-making in practical scenarios, leading to team inertia, inflexibility, and mindlessness [101]. Furthermore, mindfulness reduces intergroup bias due to mindful awareness of stereotypic and prejudiced attitudes that promote hypo-egoic behavior [102].

Relationships are critical in a team setup. Mindfulness reduces hostile behaviors by reducing irritation and anger (hostile feelings), and lessens Machiavellian tendencies, counterproductive work behaviors [103], and workplace incivility behavior [104]. Moreover, team mindfulness has been identified as a brilliant tool to preserve organizations from team conflict transformation processes. Higher task disagreement in a team causes reactivity and elevated conflict incidences, and greater task and relationship conflict, leading to higher individual social undermining. Mindfulness reduces team relationship conflict links between team task conflict and team relationship conflict, leading to downstream individual social undermining. Therefore, mindfulness would help to strengthen interpersonal relationships, favorable reputation, and work-related success in a team setup [100]. The positive association between individual mindfulness and work engagement is strengthened by team mindfulness [105].

Predominantly, organization-wide mindfulness may be critical mainly in high-risk and safety-oriented organizations [106,107]. Mindfulness also improves workgroup relationships [8], group creativity [108], employees’ basic abilities to work successfully in a team setup [19], reduces social loafing [109], and improves group cohesion, group performance, and well-being [110]. Therefore, mindful human resources may forestall team inertia and strengthen intra-team and inter-team relationships, and teamwork, and, in turn, lead to an enhanced organizational positive atmosphere, performance, and employee well-being. On the whole, mindfulness enhances positive leadership qualities, employee relationships with management and their colleagues, and teamwork, probably due to attunement of each other for their different needs with respect to people, organizations, and the environment.

2.2. Mindfulness and Employee Engagement

Kahn [111], in his significant article on personal engagement, identified that mindfulness might function as a psychological factor that improves the physical, cognitive, and emotional presence at the work role, leading to a higher connectedness to one’s job. He further emphasized that being psychologically present at work is essential for personal engagement. However, there are distractors in work situations for full presence on the work [112]. Therefore, being fully present or the present moment awareness as depicted in mindfulness theory may enhance employee engagement.

2.2.1. Mindfulness as a Personal Resource for the Job Demands-Resources Model

The widely acclaimed job demands-resources model of Demerouti et al. [113], one of the prominent job stress models among researchers, considered only job resources in the motivational process for engagement and high productivity. Subsequently, scientists identified the importance of personal resources on human behavior and health, and accordingly, the element of personal resources was also integrated into the model with job resources [114]. Grover et al. [115] proposed mindfulness as a personal resource that could be incorporated into the job demands-resources model. They also argued that mindfulness decreases stress in various pathways, such as altering perceptions of job demands, moderating job demands impact on psychological stress, and directly affects psychological stress. Janssen et al. [14] found that mindful employees were engaged, and performed better than less mindful employees under high work pressure. Furthermore, studies demonstrated a negative relationship between mindfulness and emotional exhaustion. The negative association is stronger for employees with high job demands, functioning in a supervisory role, or those who are young and single [75,116]. Scholars may attempt to find why young and single subjects behave in such a manner.

Knight et al. [117] paid attention to the growing demand in scholarship on developing work engagement interventions in their meta-analysis, and classified four major intervention categories. They also distinguished mindfulness as one of the interventions in the health-promoting interventions category that can be implemented to enhance work engagement in organizations by reducing and managing stress, leading to increased well-being and healthier lifestyles. Subsequently, the same authors advanced this finding in their later narrative systematic review. They unearthed that mindfulness interventions are the most robust intervention for effective work engagement compared to other interventions, such as leadership training and job resource building. In addition, as a specific intervention focus, mindfulness has been identified as a moderator for the effectiveness of work engagement interventions. Fittingly, they argued that after the mindfulness interventions, previously considered employees’ stressors become challenges, leading to enhanced work engagement [118] because of clear comprehension of a particular scenario for employees due to improved mindfulness and a change in their perception.

Many studies undertaken among nursing staff demonstrated that mindfulness training effectively diminishes the emotional burden, and decreases burnout [119]. Furthermore, mindfulness helps alleviate negative emotions toward self and others. Mindfulness is also helpful to retain the momentum to maintain attunement and compassion [10], whereas mindfulness training reduces social workers’ compassion fatigue and perceived stress [42]. In addition, mindfulness minimizes the positive effect of job demands on burnout, and enhances the negative effect of job resources on burnout [120]. Mindfulness-based programs significantly reduced exhaustion, cynicism, rumination, and self-criticism (a negative aspect of self-compassion), worry, minimized burnout [121,122], and increased personal accomplishment, happiness, engagement, well-being, and job performance [123,124]. Hence, mindfulness may be applicable in the job demands-resources model to reduce job stress, minimize health status degradation, stimulate engagement, and enhance positive work-related outcomes.

2.2.2. Effect of Mindfulness on Psychological Capital and Flourishing

Malinowski and Lim [125] revealed that mindfulness improved work engagement via positive job-related effects and psychological capital. They also suggested that non-reactivity and non-judging facets of mindfulness are highly influential in bolstering engagement. Similarly, recently conducted online mindfulness interventions also improved work engagement, enhanced optimism, and reduced over-commitment [126]. Another study suggested the positive facilitation influence of mindfulness on psychological attributes to identify employees’ strengths, enabling them to use those strengths actively to enhance their work engagement [127]. Conversely, the link between leader mindfulness and their cynicism was negatively mediated by their psychological capital [83].

Higher mindfulness in employees is beneficial to enhance engagement in innovative behaviors among employees experiencing low-activated negative affects, such as feelings of unhappiness, sadness, and hopelessness, by energy conservation due to minimizing ruminative thoughts and instead expending such energy for innovative strategies, consistent with the conservation of resources theory [128,129]. Accordingly, mindfulness helps to recover from work stress by avoiding stressors and worries, and in returning quickly to the original mental state, enabling employee engagement [105]. Mindfulness interventions boost employee resources required for positive organizational outcomes [130]. Junça-Silva et al. [131] argued that mindfulness strengthens the positive effective experience, resulting in a higher level of employee flourishment. Zheng et al. [132] demonstrated that mindfulness cultivates personal resources and positive emotions, leading to psychological flourishing that fosters work engagement.

In addition to previously discussed outcomes, a high mindfulness level is believed to aid in maintaining task engagement by attenuating interrupting thoughts and emotions [8]. Studies found that teleworking and role conflict negatively link with employee engagement [133]. Nonetheless, Toniolo-Barrios and Pitt [134] proposed that mindfulness training could enhance attention to work tasks, work performance, and well-being when employees work from home, with numerous distractions and challenges in the home environment. In challenging situations, mindfulness would help mitigate fatigue, particularly screen fatigue in telecommuting, and improve work-life balance. Petchsawang and McLean [135] revealed that employees from organizations that offer mindfulness training programs are more spiritual and engaged than those who did not receive such exposure.

Improved focus attention, present moment awareness, and less distraction due to higher mindfulness changes the way employees perceive things and conserve resources, which may, in turn, help in reducing stress, and allow a speedy recovery from stressful events. Therefore, the discussed published data provide compelling evidence for the significant potential of the critical construct, namely mindfulness, in enhancing employee engagement.

2.3. Mindfulness and Work Performance

Researchers suggested that mindfulness can mitigate the negative effect of emotional job demands in the organizational context based on the following findings. Both mindfulness and mindfulness interventions have a negative relationship with surface acting emotion regulation strategies. The surface acting strategies lead to increased strain, as per emotional labor theory. Mindfulness has a beneficial influence in reducing emotional exhaustion by minimizing ego depletion, and increasing job satisfaction by enhancing self-determination [32,136]. Moreover, Reb et al. [137] found that employees with a higher level of mindfulness show enhanced task performance, and lower turnover intentions. Those relationships are mediated by reducing emotional exhaustion. Mindfulness training also enhances employee psychological resilience and task performance [138], whereas character strengths mediate the relationship between intervention and task performance [16].

2.3.1. Impact of Mindfulness on Jobs with High Demand

Some professions have highly stressful job demands due to their duty’s nature. Particular attention should be paid to these professions because any mistake can cause massive damage to diverse fields in the organization. A narrative synthesis by Scheepers et al. [139] showcased that mindfulness interventions significantly affect doctors’ well-being and performance. Furthermore, mindfulness training cultivates working memory and attention, and diminishes the process of cognitive degradation and cognitive failures over time in a highly demanding work environment, such as military cohorts [140,141]. Further, mindfulness mitigates the positive association between military stress and soldiers’ hopelessness [142]. Similarly, jobs such as the auditing process involve tedious tasks. However, mindful audit staff can carry out quality audits without premature sign-off, which is very important for future decision-making [143].

Educators also undergo massive stress when dealing with students [57,144]. Therefore, administrators should pay more attention to improve academics’ mental health [145]. Emerson et al. [146] and Lomas et al. [147] identified that mindfulness-based interventions foster self-awareness decentering, regulation of attention, emotional regulation, self-compassion, empathy, and self-efficacy in their systematic reviews. Educators’ anxiety, anger, stress, depression, and burnout are minimized due to those ramifications. Similarly, the interventions cultivate positive psychological and physical outcomes in education administrators due to stress reduction [148].

Moreover, a mindful teacher who encounters a stressful situation, such as time pressure, challenges, and conflicts, is aware of their body, emotions, and thoughts (present moment awareness), resulting in reduced reactivity, enhanced kindness, and the development of social-emotional competence. Consequently, they perform their duty by slowing, pausing, and stopping where appropriate. These teachers create an environment of “relaxed alertness” for students which is conducive to learning, where the threat is minimized, and the challenge level is elevated. In addition, mindfulness interventions reduce perceived stress and the incidence of bad moods among teachers at work and at home. The rumination on work-related stuff at home partially mediates reducing bad moods, and promotes higher sleep quality at home. Resultantly, the pro-social classroom is evident with an enhanced teacher–student relationship, satisfaction, well-being, and performance [144,147,149,150,151,152]. Therefore, mindfulness interventions may be crucial for the optimum performance of professionals exposed to high demand and stress by enhancing emotional, cognitive, and behavioral capabilities.

2.3.2. Effect of Mindfulness on Employee Creativity

Continuous creativity and innovation are essential for most jobs in the ever-changing organization scenarios for their sustainability. Individuals who do not possess such abilities are under pressure in organizations. Scholars argue that mindfulness moderates the relationship between job demands and innovative work behaviors. Employees who perform with enhanced attention and focus are immersed in coping with high job demands [153]. Mindfulness has a direct positive relationship with creativity. People with higher trait mindfulness, and those who undergo mindfulness training perform better in solving insight problems, possibly due to the change of mind concepts hindered by habitual reactions originating from prior experience [154].

Ngo et al. [155] proved that the relationship between mindfulness and job performance is mediated by creative process engagement and employee creativity, respectively. They argued that employees with higher mindfulness view the problems with deeper understanding, higher clarity, less noise, and less disconnection for the creative process than the superficial understanding by less mindful employees. Mindfulness helps creativity by buffering the effect of role conflict, role ambiguity, time pressure [156], and unconscious unethical behavior [157].

Similarly, technological mindfulness enhances creative thinking, reflective thinking, high visualization, job satisfaction, employee engagement, and higher performance [37]. Moreover, technological mindfulness buffers the effect of organizational stressors on the innovative use of enterprise systems [158]. In addition to that, mindfulness is helpful in mitigating techno-stressors and job burnout [159]. Higher mindfulness is likely to enhance clear understanding, and minimize disturbances for creativity enhancement through minimizing habitual reactions and attentional gaps. Therefore, mindfulness practices are instrumental in responding to the forces affecting sustainable competitive advantage in the business world.

2.3.3. Effect of Mindfulness on Coping with Cyber Stress

With the emergence of new and sophisticated technologies, new organizational management challenges are inevitable. Employees heavily use cyber devices, such as mobile phones, laptops, and tablets, for evening cyber leisure in the current technologically developed context, especially after office hours. Prior literature suggested that employees’ mindfulness-related self-regulatory capacities help offset the negative indirect link between evening cyber leisure, and sleep quality, and sleep quantity through bedtime procrastination. The mindfulness strengthens the positive indirect link between evening cyber leisure, sleep quality, and sleep quantity, owing to evening psychological detachment by spending evening leisure wisely. This process could eventually enhance psychological vitality and the following day’s work performance [160]. Further, mindfulness reduces internet addiction via self-control [161]. Hence, the improvement of mindfulness-related self-regulation may be advantageous directly and indirectly for organizational settings to deal with the issues caused by the novel trends in this complicated environment.

2.3.4. Impact of Mindfulness on Financial and Economic Performance

Financial and economic decision-making is a risky process in organizations. Failures in making appropriate decisions cause harmful repercussions for individuals and organizations as a whole. Financial mindfulness is identified as “openness and attention to, and awareness of, present financial events and experiences”, which could help relieve financial pain [162]. Researchers suggested that mindfulness is crucial in financial planning, investment portfolio management, maintaining a successful client and advisor relationship, endurance in financial market turmoil, and better financial decision-making [163]. Employees are in stressful conditions when an organization is on the verge of a financial or economic downturn or collapse. However, higher individual mindfulness leads to greater organizational mindfulness, enabling organizations to identify small-scale failures and anomalies at the organizational level proactively. The detections would be helpful to preclude economic losses and massive failures, and improve innovativeness, leading to enhanced organizational performances [164,165].

In the meantime, the underlying mechanism of Thailand’s sufficiency economy philosophy is believed to be ascribed to the fact that mindful managers identify external risks, and make appropriate business decisions [166]. The business decisions could minimize the firm-specific risk without compromising performance, and promote this economic philosophy considering shareholder wealth maximization [167]. Therefore, mindful awareness of leaders and employees may positively influence the organization’s better financial and economic health, as they would be well aware of financial and economic factors affecting the organization’s performance.

2.3.5. Mindfulness and Green Performance

The effects of emerging green concepts are essential for human health and a sustainable world. Overall organizational mindfulness is critical in implementing green concepts that require conceptual support from all organization levels [168]. Green mindfulness is crucial to appropriately understand economic and social green motives [168,169]. A study identified that mindfulness positively links with pro-environmental behavior via connectedness to nature [170].

Scientists explored that green shared vision has a positive indirect nexus with green creativity through green mindfulness [169]. Moreover, green transformational leadership has an indirect relationship with green performance through green mindfulness [171]. Therefore, mindfulness may boost green mindfulness and green practices in organizations, leading to organizational and environmental sustainability. Sustainability is achieved by reduced automaticity, greater pro-sociality, recognition of intrinsic values and openness to novel experiences, strong connectedness with nature, improved health, and subjective well-being. Accordingly, individual behavior changes due to higher mindfulness may effect positive societal changes [172]. In summary, employees’ performance and sustainability of the organization and the environment are enhanced by employees’ mindfulness due to minimized attention gaps and automaticity, and increased clear comprehension about the true nature of related phenomena.

2.4. Mindfulness and Employees’ Well-Being

In recent years, attention to employee well-being has emerged as a vital aspect of organizational science. Several positive impacts of improved employees’ well-being in a corporate environment are low sickness levels, reduced job turnover rates, and a highly hardworking, productive workforce. In their seminal study, Brown and Ryan. [36] highlighted that mindfulness is a crucial factor in psychological well-being. This claim has been proved using quantitative and qualitative methods [42]. Prior research has cued that mindfulness directly, and through positive job-related effects, hope, and optimism, enhances general well-being [125] and mental well-being [83].

Furthermore, evidence showcases that mindfulness heightens positive affect, self-care, and life satisfaction, and lowers psychological strain, negative affect, and health complaints. Prior research also suggests that attentional and non-judgmental facets of mindfulness may develop greater emotional intelligence. In turn, intrapersonal and interpersonal adaptive functioning associated with emotional intelligence results in higher well-being [40,173] and performance [93]. Moreover, loving-kindness meditation practiced by working adults cultivates mindful attention, mindfulness, compassion, social support, and social connections, leading to minimizing depression, and improving subjective well-being (life satisfaction and emotional balance), quality of life, physical health, and spirituality, and overcoming the hedonic treadmill effect with the broaden-and-build theory [99,174,175,176,177].

Wolever and colleagues demonstrated the effectiveness of the mindfulness training program at Aetna Inc. to reduce stress, and enhance sleep quality [56,178]. Similarly, the Trivago Flowlab showed positive effects on sleep quality by mindfulness interventions [179]. The way employees spend their time after work hours could be an influential factor in their work performance. The scholarship has demonstrated that higher mindfulness is positively associated with psychological and physical well-being-related dimensions, such as co-workers’ daily positive affect, psychological detachment after work, relaxation experiences, sleep quality, sleep duration [43,160,180,181,182,183], happiness [123], enhanced relationship satisfaction, minimized work–family conflicts [31,184,185], work–life enrichment [130], quality of life [122], reduced enacted incivility [104], reduced incidence of bad moods, enhanced satisfaction at work and home, and minimized daytime sleepiness and insomnia symptoms [151].

The existence of the phenomenon of gain spirals has been identified in the relationship between mindfulness and recovery experiences [186]. Mindful behavior may play a more dominant role in the following day’s performance, such as organizational citizenship behaviors [181]. These findings align with two prominent theories: the conservation of resources theory, and the broaden-and-build theory. The accumulated resources after working hours as positive emotions would be spent in the next day’s work, exhibiting positive outcomes [129,187].

Siegel [188] introduced mindfulness as human’s best friend, and accentuated the immense potential of mindfulness to make a world of compassion and well-being. He also described that intra- and interpersonal attunement is improved and reinforced by each other due to focused attention, mindful awareness, and self-regulatory functions. Therefore, mindfulness improves loving-kindness and compassion, which will develop intentions to look after the well-being of oneself and others in turn. Further, mindfulness interventions improve common humanity [189]. Shi and He [190] asserted that mindfulness generally reduces high self-referential processing in human beings, and reinforces other-referential processing to attain an equilibrium of mental activities toward others and oneself, which is crucial for pro-social behavior.

The social mindfulness concept assuages the adverse effects of customer mistreatment, and employees’ evening negative mood [191], and improves customer orientation [192]. Therefore, social mindfulness is a fundamentally important aspect of pro-social motivations. The qualities mentioned earlier may act as other-regarding motives, and initiate other-regarding actions, resulting in mutual well-being, as mentioned above [193]. In addition, scholars argued that mindfulness interventions could be used as soft management control systems to enhance occupational health and safety, improving individual, organizational, and societal sustainability. [11,194]. Therefore, greater emotional intelligence, and intrapersonal and interpersonal adaptive functioning cultivated due to higher mindfulness, help in improving well-being. Mindfulness also assists in precluding and combating employees’ strain in and outside the working environment. Consequently, positive cognitive, emotional, physiological, and behavioral outcomes due to mindfulness are crucial for ameliorating both leaders’ and employees’ well-being and health, indirectly affecting societal well-being, health, and sustainability.

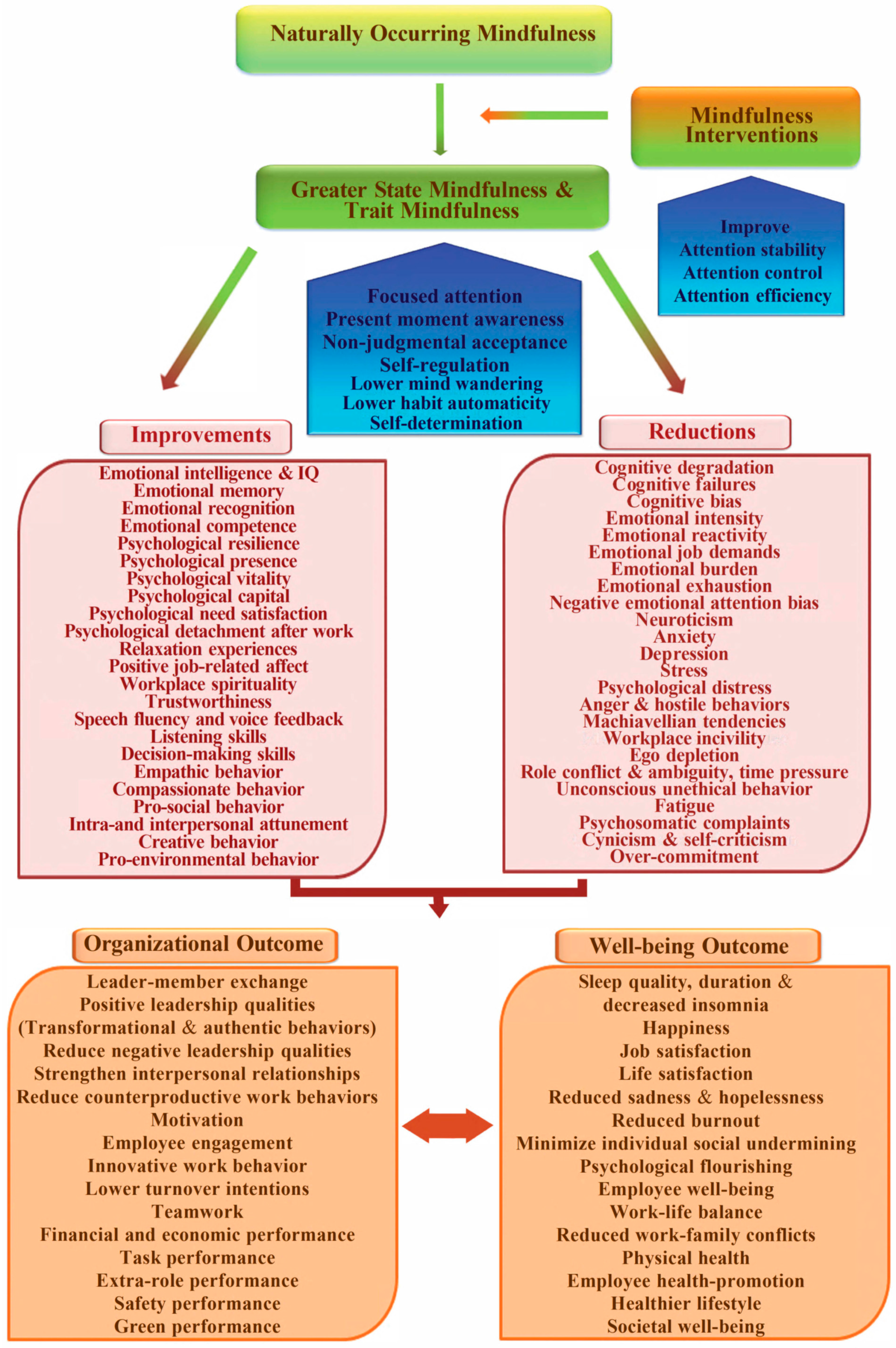

An overview of the effects of mindfulness interventions on employees and organizations is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of effects of mindfulness.

3. Discussion

Although we observe a growing trend in applying the mindfulness concept in many disciplines, including organizational management, there is still a controversy on the implementation of mindfulness interventions, and the exact mechanisms of action of mindfulness have not been illustrated fully. Hence, this review focused on mindfulness research progress, particularly during the previous five years. On the whole, there is a groundswell of scholarly support that mindfulness training programmes can be undertaken in the organizational context based on recently developed theoretical backup so as to improve performance and employee well-being.

3.1. Theoretical Contributions

This review identified the causative processes due to higher mindfulness that generate positive cognitive, emotional, physiological, and behavioral outcomes: focused attention; present moment awareness; non-judgmental acceptance; self-regulatory functions; lower mind wandering; lower habit automaticity; and self-determination. Accordingly, employees may change the way they perceive things, and set up all inner resources to endure problems at work, leading to optimizing their state of functioning. Mindful individuals experience a calm and clear mind even at a high emotional demand. Mindfulness remarkably reduces the experience of negative affectivity, improves the experience of positive affectivity, and maintains mental equilibrium between self and other referential processes, leading to lower stress, higher performance, pro-sociality, and higher well-being.

As a personal resource, mindfulness can be incorporated into the well-accepted stress model of the job demands-resources model of Demerouti et al. [113]. Accordingly, the motivational path of the model is activated, resulting in beneficial effects of higher employee engagement and performance, and the stress pathway is suppressed, which is beneficial to maintain a healthier life. As such, mindfulness may be helpful to improve the deteriorated health of employees, and forestall worsening health conditions of employees. In most cases, healthy persons may become a resource compared to unhealthy subjects for organizations and society. The healthier employees would contribute immensely in various ways, such as in minimizing sick leave, the organization’s health budget, and turnover intentions, leading to enhanced engagement and better organization performance. Therefore, mindfulness is a vital societal growth factor that ameliorates the salubrious effects of humans.

In addition, reduced mind wandering due to mindfulness could be used as a facilitator to preserve psychological resources for essential functions as per the conservation of resources theory [129]. Employees would utilize these preserved resources to make a positive psychological effect on organizational functions by preventing stressors, and recovering stress and worry quickly, and by catalysing psychological flourishing, leading to engagement, higher performance, and higher well-being. The evidence stipulated in this review justifies that mindfulness and meditation application is crucial in improving relationships, stress reduction, motivation, employee engagement, performance, and well-being in organizations due to the positive influence of high mindfulness on cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and physiological domains. Hence, this powerful trait contributes theoretically and practically in the organizational work context extensively to develop employees’ mental and physical health to flourish, improve a wide array of superior organizational outcomes, and warrant organizational success and sustainability.

3.2. Practical Contributions

In light of the mindfulness findings, we strongly encourage incorporating state and trait mindfulness measurements for recruitment and promotional tools, especially for stressful jobs. Mindfulness interventions can be used as the most influential training method to improve employee engagement [117]. As depicted in Figure 1, mindfulness enhances positive leadership qualities, employee relationships with management and their colleges, teamwork, employee engagement, performance, well-being, and sustainability. Accordingly, this review identified the great potential of mindfulness interventions that can be implemented in the workplace to improve individual, organizational, and societal sustainability.

3.3. The Future Research Directives on Mindfulness

Previous findings justify the need for further advancement of the mindfulness concept, and are useful to identify new opportunities to develop job performance and employee well-being. The work presented in this review has been predominantly concerned with the positive aspect of mindfulness, the most overarching parameter applied in the organizational context. Conversely, inconsistencies exist in the positive outcome of mindfulness in the literature. Some scholars anticipate some adverse effects of mindfulness, such as more personal interest may be developed rather than organizational interest by the employees [10,32]. Hence, understanding those claims is crucial for identifying them, and taking alternative remedial measures to rectify any adverse influence of mindfulness in organizations. Despite the fact that a multitude of mindfulness work has been reported in the literature, the effect of mindfulness on the workplace has not yet been sufficiently studied. More future work needs to be focused on diverse organizations to improve the generalizability of mindfulness research findings, as most of the existing workplace evidence represents healthcare workers. Due to limited attention on the link between mindfulness and employee commitment for societal sustainability factors, such as social justice, human rights, customer well-being, work-family enrichment processes, and other related societal issues, a great deal of work still needs to be done in this area. Thus, further research is required, as the workplace gains of mindfulness have not been fully established.

Mindfulness training programs are currently conducted in the organizational setting. Nevertheless, many mindfulness training methods are implemented without considering organization-specific contextual factors and empirical findings [8,178]. Mindfulness programs are helpful to be conducted for more homogeneous populations to identify the program’s influence on a particular population [195]. In addition to that, employee acceptance of various interventions needs to be evaluated to identify sustainable programs that can be delivered continuously. In order to identify the effective mode of delivery, face to face, online, teleconferencing, recordings, written materials, or a combination of those modes, need to be investigated. Therefore, applied research has to be performed in the future to identify optimum contemplative designs for various organization sectors to enable organizations to achieve higher efficacy and sustainability [8,33,196]. Although mindfulness programs enhance leadership qualities, scholars are unable to find the most appropriate mindfulness training program to develop managers’ leadership competencies [84]. Therefore, scholars may attempt to uncover the impact of mindfulness on different leadership behaviors, and to find the best mindfulness interventions for different employee categories in the organization setup.

Moreover, mindfulness trainers are argued to be familiar with a particular organization context, specifically in high-demand settings, which may produce more results than ordinary experts in mindfulness training. Therefore, more empirical attention should be paid to this connection to facilitate the designing of mindfulness training programs [197]. Contextual mindfulness training programs must be developed to suit the particular cohort. For example, mindfulness-based attention training (MBAT) is designed for elite military service members, and conducted by experts with exposure to a military setup for a considerable period [141]. Therefore, future research may focus on the practical requirements of the organizations, and attributes of the trainer, such as their experiences, for empirical validation.

Scholars recommended incorporating scientifically validated mindfulness interventions into organizational training and workplace health promotion programs [32,47]. There are different types of mindfulness interventions. Therefore, scientists should investigate the best intervention type, intervention content, level of guidance, practice frequency, session length, practice duration, class sizes, effect sustainability, and requirement and time lapse of refresher programs, since the effects of the interventions follow different magnitudes and mental functions, and deliver behavioral outcomes based on the discussed factors. Thus, empirical evidence is needed on a particular mindfulness training program that delivers sustained specific organizational requirements [72]. For example, some employees have deficits in executive functioning, such as working memory, problem-solving, emotion regulation, impulse control, self-motivation, and others [71]. Therefore, the researchers of the present study stress the need to design and validate training programs to address these specific aspects in future studies to mitigate the adverse effects of such deficiencies among employees by using mindfulness interventions.

After incorporating mindfulness training programs into existing organizational training programs, their synergistic effect should be appropriately tested. Organizations are conducting various training programs for their employees. A mindfulness training module can be incorporated into some programs, such as leadership training or motivational training. Minzlaff [198] argued that combining three components in an integrative coaching model comprising mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral coaching, and motivational interviewing would reduce problematic behaviors, and enhance employees’ performance and well-being compared to individual training programs. Therefore, future researchers may investigate the combined effect of various training programs inclusive with a mindfulness component rather than those conducted alone.

Scholars observed that the positive link between COVID-19 fear and job insecurity was mitigated by employee mindfulness [199]. Therefore, researchers may investigate the theoretical implications of employee mindfulness on organizational outcomes, such as performance and well-being during times of crisis. Besides, the positive relationship between mindfulness and employee readiness for change in a crisis is strengthened by well-being, and weakened by distress; possibly, such mental health conditions change the capacity for self-regulation [200]. Scholars found that past financial performance, firm age, and slack resources moderated the link between managerial mindfulness, and research and development (R&D) intensity. Krick and Felfe [173] discovered that mindfulness interventions are more beneficial for individuals with higher neuroticism and openness. Accordingly, moderation effects of factors, including demographic variables (age, gender, education, ethnicity) and organizational culture, should be evaluated. For example, employee age may be investigated in the relationships of mindfulness, since age-related cognitive and emotional differences exist. The influence of the intervention on performance and job satisfaction is mediated by emotional stability and agreeableness [54]. Therefore, circumstances where employees’ mindfulness facilitates or hinders organizational performance and well-being should be understood further. As such, future studies may focus on mindfulness as a moderator, mediator, and moderated mediation of workplace-related relationships.

The identified possible antecedents of mindfulness include workload, psychological detachment, sleep quality, pain, family issues, supervisor support [201], and quality of leader–member relationships [202]. Further, Said and Tanova [203] found that workplace bullying reduces the level of state mindfulness, leading to higher employee emotional exhaustion. Studies on the antecedents of mindfulness seem to be somewhat neglected in the literature. Therefore, identifying the individual, group, workplace, and social level antecedents, boundary conditions, and underlying processes are crucial, and studying the effectiveness of mindfulness on various management-related variables, potential mediators, and moderators between the relationship in work settings is imperative. Many studies on mindfulness focus on trait characteristics of mindfulness; however, the effect of state mindfulness (that changes moment to moment) on organizational outcomes has to be evaluated more in future studies [131,203]. Further studies are suggested to identify the particular effect of the dimensions of mindfulness on personal or workplace outcomes. For example, the non-judgmental facet may be more influential in stress reduction. Therefore, future researchers should be further committed inclusively to advance mindfulness conceptualization and operationalization at work with methodologically more rigorous designs.

Somewhat fewer studies have focused on the effect of collective mindfulness on organizational outcomes, and the effect of mindfulness on green performance. Hence, an extensive understanding of the effects of organizational mindfulness, and mindfulness on workplace green initiatives are required in future work. Many scholars have attempted to investigate the positive effects of high mindfulness. However, future work is suggested to explore the adverse effects of employees’ low mindfulness to understand how low mindfulness is disastrous for organizational performance and employee well-being. Future researchers should attempt to engage in randomized controlled studies in diverse samples from different employees and organizations with larger sample sizes and more longitudinal studies. There is ample scope for further work in this nascent concept in organizational science. Therefore, researchers are encouraged to undertake more rigorous research designs with field experiments or quasi-experiments.

3.4. Limitations

As the current review is a qualitative narrative review, effect size estimates of various outcomes are not measured. In addition, the authors’ subjectivity in reviewing sources is another limitation of this study. However, the findings presented in this review can be extended with systematic meta-analytic reviews in future work for a more systematic understanding of the mindfulness concept.

4. Conclusions

As per the first objective of this review, we demonstrated the most relevant developments of the mindfulness concept concerning organizational science, especially during the last five years, to comprehensively assimilate the concept. Overall evidence in this review postulated a high level of validity that mindfulness and meditation applications are vital in improving positive psychological movements, such as relationships, motivation, employee engagement, performance, and well-being, in organizations, owing to the beneficial impact of increased mindfulness on optimal functioning of cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and physiological realms. As such, this robust concept should be widely implemented in the organizational work setting to promote employees’ mental and physical health, enhance a variety of superior organizational outcomes, and ensure the organization’s success and sustainability.

In line with the promising results of prior research, mindfulness helps prevent employees’ strain inside and outside the working environment. Mindfulness meditation has a high potential to forestall psychological disorders of employees. It might facilitate cultivating a healthy mind, body, relationships, and an improved well-being to thwart adverse effects on human health. Accordingly, mindfulness promotes planetary health [204]. Hence, mindfulness and meditation techniques help to develop better organizational performance, well-being, a more compassionate society, and a sustainable world.

It is noteworthy that we characterized the causative processes of higher mindfulness as leading to positive cognitive, emotional, physiological, and behavioral outcomes: focused attention; present moment awareness; non-judgmental acceptance; self-regulatory functions; lower mind wandering; lower automaticity; and self-determination.

We outlined a comprehensive future research agenda as another key contribution of this composition. Predominantly, scholars need to develop a widely accepted definition, and the concept should be operationalized for work contexts. The review highlighted a significant scope for more research on mindfulness as a moderator, mediator, and moderated mediation. Very few studies exist on antecedents of mindfulness in the literature compared to studies on the consequences of mindfulness. Hence, future research endeavors are encouraged to explore those aspects.

The researchers hope that this novel integrative review fuels additional research to gain in-depth insights and knowledge. Thus, the use of these practices will increase in a wide range of everyday contexts in organizations among scientists, practitioners, and those who may be a little puzzled or anxious about the concept, as this review validates the positive influence of mindfulness in professional settings. Conclusively, mindfulness would become a key teaching–learning component in the mainstream management context to increase employee performance and well-being, and be the foundation for a successful organization and sustainable world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.N.K.W.P. and Z.C.; methodology, P.N.K.W.P. and Z.C.; validation, P.N.K.W.P. and Z.C.; formal analysis, P.N.K.W.P. and Z.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.N.K.W.P.; writing—review and editing, P.N.K.W.P. and Z.C.; visualization, P.N.K.W.P. and Z.C.; supervision, Z.C.; funding acquisition, Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by key Projects of Chinese National Social Science Fund Grant 20AZD019; 17AGL014, and Huazhong University of Science and Technology Special Funds for Development of Humanities and Social Sciences Grant HUST2019.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness; Random House, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Nyanaponika, T. The Heart of Buddhist Meditation: The Buddha’s Way of Mindfulness; Weiser Books: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goilean, C.; Gracia, F.J.; Tomás, I.; Subirats, M. Mindfulness in the workplace and in organizations. Pap. Del Psicol. Pap. 2020, 41, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredze, J.M. Albert Ellis and Mindfulness-Based Therapy: Revisiting the Master’s Words a Decade Later. J. Ration. Cogn. Ther. 2020, 38, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, P.K.; Lee, R.A.; Mills, M.J. Mindfulness at Work: A New Approach to Individual and Organizational Performance. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 8, 576–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.M.G.; Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness: Diverse perspectives on its meaning, origins, and multiple applications at the intersection of science and dharma. Contemp. Buddhism 2011, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, L.G.; Marshall, N.J.; Motala, A.; Taylor, S.L.; Miake-Lye, I.M.; Baxi, S.; Shanman, R.M.; Solloway, M.R.; Beroesand, J.M.; Hempel, S. Mindfulness meditation for workplace wellness: An evidence map. Work 2019, 63, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, D.J.; Lyddy, C.J.; Glomb, T.M.; Bono, J.E.; Brown, K.W.; Duffy, M.K.; Baer, R.A.; Brewer, J.A.; Lazar, S.W. Contemplating Mindfulness at Work. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 114–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-M.; Chen, T.-J. Inspiring prosociality in hotel workplaces: Roles of authentic leadership, collective mindfulness, and collective thriving. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glomb, T.M.; Duffy, M.K.; Bono, J.E.; Yang, T. Mindfulness at work. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Joshi, A., Liao, H., Martocchio, J.J., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011; Volume 30, pp. 115–157. [Google Scholar]

- Sajjad, A.; Shahbaz, W. Mindfulness and Social Sustainability: An Integrative Review. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, K.; Julliard, K. Implementation of a Mindfulness Moment Initiative for Healthcare Professionals: Perceptions of Facilitators. Explore 2018, 14, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melchior, M.; Caspi, A.; Milne, B.J.; Danese, A.; Poulton, R.; Moffitt, T.E. Work stress precipitates depression and anxiety in young, working women and men. Psychol. Med. 2007, 37, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, E.; Van Strydonck, I.; Decuypere, A.; Decramer, A.; Audenaert, M. How to foster nurses’ well-being and performance in the face of work pressure? The role of mindfulness as personal resource. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 3495–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reb, J.; Narayanan, J.; Chaturvedi, S. Leading Mindfully: Two Studies on the Influence of Supervisor Trait Mindfulness on Employee Well-Being and Performance. Mindfulness (N. Y.) 2014, 5, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, D.; Ruch, W. Fusing character strengths and mindfulness interventions: Benefits for job satisfaction and performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]