1. Introduction

Transitioning to a more sustainable society is a challenging task for organizations as well as individuals, requiring a managerial approach capable of addressing such complexity [

1,

2]. It is evident that sociotechnical transitions [

3] are complex, long-term, evolving phenomena, and as such, they cannot be directed in command and control terms, but rather require the development of coordinated multilevel processes (individual, organizational and system-level) [

4]. However, Rotmans and Loorbach [

5] argue that it is still possible to influence and guide, in terms of shaping the emergence and direction of these processes. Still, previous research on transition management provides limited insights into how individuals and organizations can, might, or should act in the present to affect processes of transition or to steer trajectories towards desired goals [

1,

6].

In this paper, we focus on the role of individuals in transition processes, specifically in an organizational setting. The transition management literature has highlighted the need for frontrunners taking part in transition processes, an exclusive group of individuals with quite specific characteristics [

5,

7,

8,

9]. They should be visionaries and frontrunners, open-minded and able to look beyond their own domain or working area. Such individuals are essentially boundary spanners—individuals with specific relational skills and competences to bridge diverging perspectives as well as facilitate the dissemination and integration of new information and knowledge into an organization [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Being a boundary spanner also entails navigating power dynamics in managing complexity, understanding motives, roles and responsibilities in “the big picture”, having insights into organizational strategies and visions, as well as knowing how and who to influence in order to obtain authority and legitimacy to drive change in an organizational context [

10,

11,

15].

As more and more organizations recognize the importance of sustainability transitions, there will be a large demand for skilled individuals capable of engaging in such processes [

11]. Whether they span internal or external boundaries of the organization, such individuals become critical change agents in organizations [

16] and essential in preparing the organization for sustainability transitions. As proposed by Smink, Negro [

17] and Goodrich, Sjostrom [

11], further research into boundary spanners’ activities, skills, and training is warranted because it can increase organizations’ capability to create and exploit transition opportunities.

Previous research has highlighted actions and behaviors of boundary spanners [

12,

18,

19] but has placed little emphasis on how boundary spanners emerge and how the necessary skills and competences can be supported, e.g., through training [

11,

20]. As a consequence, the processes through which individuals become boundary spanners “in practice” needs further attention [

14,

15,

21]—specifically, how organizations can enable individuals (formally designated or not) to take on this role and develop the skills and competences needed to become successful boundary spanners. As argued by Goodrich, Sjostrom [

11], the diversity of skills associated with boundary spanning functions are often not explicitly taught in pre-career academic or professional training and may be ad hoc or emergent for professionals, who are confined to a “trial-and-error” approach [

22].

This paper draws upon a longitudinal study of a large Canadian energy corporation, Hydro-Québec, attempting to increase and strengthen the organization’s sustainability orientation. Between 2015 and 2017, the organization engaged in a selection of its research and engineering staff in an innovative design method training program organized and directed by management and design scholars at a nearby university. In this paper, we illustrate the role of such training through the experiences and trajectories of four individuals taking part in the program, who, among all the participants, gradually assumed this new role of boundary spanners. We elaborate on how the training supported and enabled them to take on boundary-spanning roles by addressing the following research questions:

What are key characteristics that enable individuals to engage as boundary spanners, as well as the boundary conditions for assuming this role?

How and in what ways can a design training program contribute to the emergence of boundary spanners?

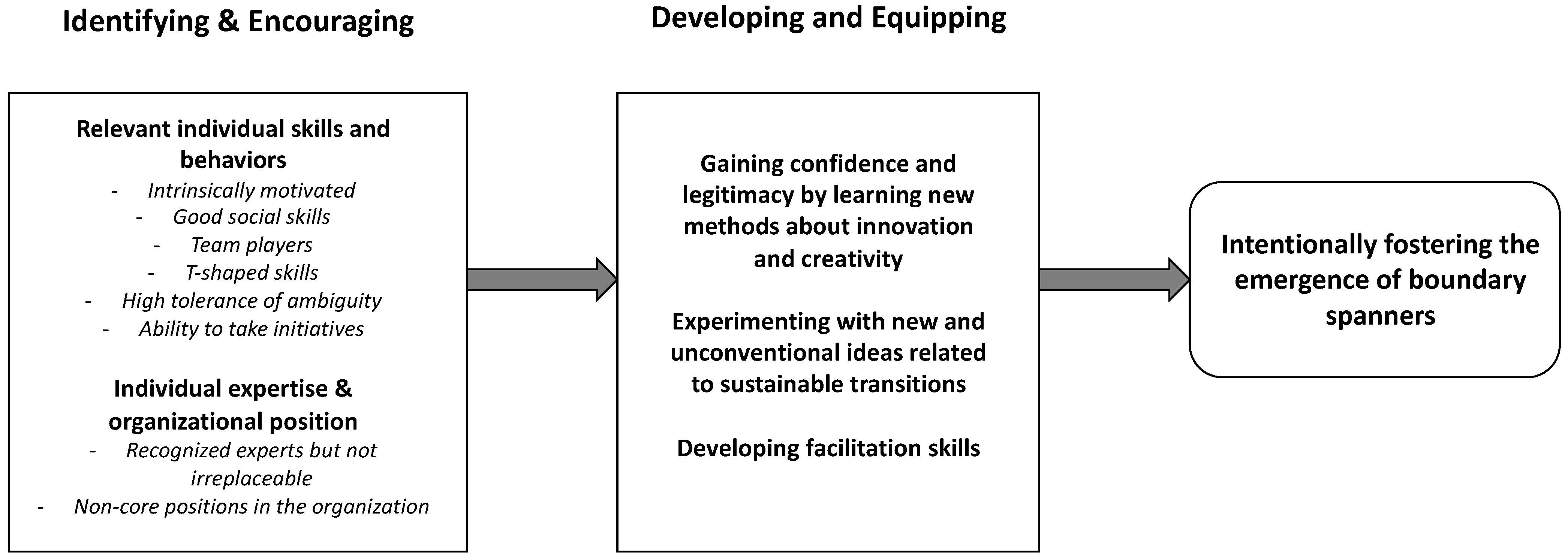

Answering these questions, our findings contribute to the literature on transition management by first identifying and explicating key characteristics in terms of relevant individual skills and behaviors, as well as in terms of individual expertise and organizational position. Secondly, our study highlights the process by which organizations can support and enable the emergence of these boundary spanners through design trainings that provide a dedicated safe space for these individuals to be reflexive and experiment with new alternatives that the organization could explore toward sustainability transitions.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Individuals in Transition Processes

Transition management is about fostering sustainability transitions from a system perspective [

8], where participatory, collaborative processes involving multiple actors and individuals are considered essential to reach the ultimate goal of sustainability. In fact, recent literature often presents the need for intermediary actors and organizations to navigate the fluid boundaries between adaptation and transformation in sustainable transitions [

16,

23,

24]. Still, the framework of transition management is lacking in detail as to how organizations and individuals can in practice and prepare to engage in transition processes inside as well as outside of the organization. It is not always easy to make a diverse group of individuals work together in a joint direction [

25], and collaborative processes can be challenging not only on an organizational level but also on an individual level for many reasons, such as unclear expectations, lack of a common language, diverging institutional logics, organizational politics or lack of appropriate management [

26]. Especially when dealing with sustainability issues that challenge the existing order, Rotmans and Loorbach [

5] argue that there is a need to consider the plurality of interest, values and prospects of a wide range of societal parties which contributes to the complexity.

As a consequence, taking part in transition processes requires a great deal from the individual participants, yet scholars [

27] have demonstrated that very little attention has been dedicated to explore the microfoundations of corporate social responsibility and activities to support sustainable transitions [

28]. Recently, López Reyes, Zwagers [

29] has drawn attention to the need to consider more carefully the “Human-Dimension” to make sustainable transitions actionable. According to Rotmans and Loorbach [

8], participants in transition processes need to have some basic skills and competences at their disposal, preferably being visionaries with the ability to look beyond their own domain or working area and be open-minded. While the participants do not have to be experts in their own field, they do need to be willing to invest time and energy in the process of innovation and commit themselves to it. According to [

5], these frontrunners should have the following:

The ability to consider complex problems at a high level of abstraction;

The ability to look beyond the limits of their own discipline and background;

They enjoy a certain level of authority within various networks;

The ability to establish and explain visions of sustainable development within their own networks;

They can think together;

They should be open for innovation instead of already having specific solutions in mind.

These qualities appear to matter as participants need to comprehend each other’s ideas, motives and vision and develop a better understanding for each other, in order to be able to search together and develop a common agenda [

5]. Still, making this work in practice is a challenge, as research shows that participants are often not equipped or used to working in this way in heterogeneous groups, operating in a free-format style [

30]. Nevens, Frantzeskaki [

31] identified a number of challenges relating to, e.g., the selection of genuine frontrunners, identifying and excluding members that do not contribute as desired, working for a certain period of time without very tangible results and still keeping up motivation and overcoming dominance of “stakes” and representation in favor of personal commitment. It has also been shown that a large degree of freedom can make participants feel insecure, which is difficult to overcome [

30,

32]. However, after a while, it appears that most participants find this setting very stimulating, enabling them to come up with some creative and innovative ideas [

30]. Another concern is the long-term impact of transition projects, where a study by Gössling, Hall [

33] following experiences of transition projects raised doubts about the effects of transition projects, due to participants’ lacking the necessary capabilities to integrate the learnings further into concrete actions within their daily organizational environment.

2.2. Boundary Spanners as Agents of Change in Sustainable Transitions

In the context of sustainability transitions, which require extensive collaboration and knowledge exchange among multiple actors, the value of individuals with specific skills has been noted [

9,

11,

12,

34]. For example, Hassink, Grin [

35] suggest that individuals with dual identities or organizational affiliations, who are able to combine, e.g., entrepreneurial and institutional behavior, can be critical in facilitating interactions across system boundaries, specifically initiators of collaboration in the care farming sector. Similarly, Smink, Negro [

17] describe how “boundary spanning” individuals step in to increase mutual understanding and forge productive working relationships among diverse actors in niche-regime interaction. However, the actors still struggle with the existing differences in institutional logics, which can hinder the transition towards more sustainable solutions [

11].

Thus, it does not appear surprising that in complex contexts characterized by uncertainty and change, there is a need of individuals who can bridge the divide between different parties (within or between organizations) and thereby connect different worlds [

12,

36]. Research on inter-organizational collaboration as well as in organizational behavior and strategic management has long recognized the value of such boundary spanning individuals [

13,

14,

18,

37,

38], although sometimes referred to by other names such as networker, broker, collaborator, cupid, civic entrepreneur, boundroid, sparkplug or collabronaut [

39]. Boundary spanners need not be individuals with a formally designated or nominated role; the roles may also be performed in practice by individuals without such nomination [

11,

15].

Several scholars have sought to classify the roles that boundary spanners are expected to perform [

10,

18,

37], concluding that this in fact constituted a bundle of skills, abilities and personal characteristics, which together result in effective inter-organizational behavior. Examples mentioned are

“building and maintaining relationships, managing within non-hierarchical environments, managing complexity and understanding motives, roles and responsibilities” [

10] (p. 103). This is accomplished by individuals through their ability to understand, empathize, build trust, and resolve conflicts. By acting as a go-between, they can essentially act as a translator by transposing ideas and thereby increase the potential “solution space” of a problem by raising other’s awareness of alternatives [

40].

Williams [

10], Saldert [

41] also note that boundary spanners manage such relationships through influencing and negotiating in highly politized environments, within organizations as well as in multi-actor collaboration. These individuals manage complexities and interdependencies and are capable of integrating strategy and implementation, e.g., seeing the big picture. This is based on an understanding of multiple roles, accountabilities and motivations in organizations, which can only be achieved by being exposed to multiple or contradictory logics, provoking reflection on these logics [

11,

40]. Williams [

10] argue that an individual disposition towards innovation, experimentation, risk-taking and entrepreneurship is essential for a boundary spanner battling complex problems, in contrast to striving towards a single “right” solution.

While boundary spanning is typically related to inter-organizational relations, it also occurs within organizations where the boundary spanners become change agents implementing change initiatives across internal organizational boundaries, also known as “boundary shaking” [

42]. Balogun, Gleadle [

42] describes how acting as a change agent within an organization in fact requires the same skills and competences and entails the same kind of practices that an “externally oriented” boundary spanner engages in. In fact, they may need to be even more conscious of dimensions of power and politics to succeed and rely heavily on influencing tactics to frame the change in a suitable way, mobilize support and obtain access to resources (ibid).

The multiple roles of a boundary spanner can easily come into conflict, and may lead to stress or burnout [

11,

43,

44], and in general terms, there are only few accounts of the “lived experience” of boundary spanners [

11,

42]. The pressing question is that we still know little of how boundary spanners emerge, or what mechanisms organizations can put in place to encourage their emergence. As expressed by [

11] there is a lack of training, recognition, and evaluation to adequately support boundary spanners in sustainable transitions. While there are examples, in practice, of courses and training programs focused on, e.g., enhancing communication and relation-building skills [

45] or strategic planning and project management [

46] and change management [

47], there still seems to be room for more comprehensive training opportunities that focus on identifying, rapidly assessing, and working to align different worldviews, values, priorities, and frameworks, to increase boundary spanning capacity and develop additional professional pathways [

11].

3. Empirical Context and Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This paper is based on data collected from a longitudinal qualitative single-case study [

48,

49], conducted between 2015 and 2017 within Hydro-Québec research center, a large organization that began to engage its teams in a transition to explore new avenues in the field of energy. Between 2015 and 2017, Hydro-Québec selected 40 members of its research and engineering staff to participate in an innovative design training program organized and directed by management and design scholars at a nearby university. The implementation of this training program led to the development of new individual competences as well as a shared language to address innovation and sustainability, but also so transformed the attitude and role of many participants within the organization. The case study represented a unique opportunity to capture the operational aspect and individual level of sustainable transition processes in the making in a firm seeking to renew its innovative direction, and thus it serves an illustrative purpose [

50]. In this paper, we specifically focus on the experiences and trajectories of four individuals who, among all the participants of the training, gradually assumed a new role as boundary spanners. We analyze the characteristics of these individuals as well as their trajectories to understand the conditions and factors that enabled them to take on the critical role of boundary spanners.

Two of the authors, who also participated in the design and execution of the training program, had the opportunity to observe and follow the innovative design training program to monitor its effects, and one author participated as an observer during several workshops in one of the cohorts. This implied that at least one of the authors was always physically present at most of the workshop days, observing and interacting with participants and organizers to understand what was happening and at the same time becoming immersed in the process. Following this first study, one of the authors conducted an ethnography for eight months in the organization [

51,

52,

53]. This provided the opportunity to extend the contact with many participants of the training program and follow their initiatives and personal trajectories.

3.2. Empirical Context: Training for Innovation and Sustainability at Hydro-Québec

Hydro-Quebec is the dominating state-owned actor in the energy industry in the Quebec province in Canada. As its core business, it takes care of production, transportation, and distribution of electricity in the province, based on the vast local resource of hydropower (for 99% of its operations). As such, its position has been relatively secure in terms of lack of competitors and a renewable and affordable way of producing electricity, which means that up until now, the organization has mainly focused on keeping up existing activities and maintaining their assets and infrastructure.

Hydro-Québec is the only power company in North America with a considerable research institute: The Hydro-Québec Research Institute (IREQ). With over than $100 million per year in R&D investment, IREQ includes approximately 500 scientific researchers, engineers, and specialists, who work at supporting all Hydro-Québec operations and development of scientific research in the field of energy, therefore actively pushing innovative ideas into the rest of the organization.

Still, at the mid-2010s, circumstances began to change and the Hydro-Québec top-management has started to recognize that there is most likely untapped value potential in the organization, which could be exploited to bring back greater profits to the Quebec taxpayers. Furthermore, the organization is not immune to the global sustainability debate and is experiencing growing pressure to explore novel ways to contribute to economic and social sustainability in Quebec and Canada and reduce greenhouse gas emissions in line with international political agreements. In addition, the energy market is in transition with new decentralized energy resources (such as solar panels, wind, batteries and electric vehicles, microgrids), the expected arrival of new players on the market, and new emerging technologies (ranging from blockchains, artificial intelligence, to battery storage capacities).

As part of a transformation to a more radical innovation plan, a training program in innovation design for IREQ staff was initiated and organized by three management and design researchers at two of the universities in Montréal (two of whom are authors of this paper). The training program involved two cohorts of 20 researchers each from IREQ. The total 40 participants were selected from all divisions of IREQ and were carefully chosen based on the importance of their technical expertise within the research center, as well as their personal attitude towards creative processes (ranging from comfort in unusual situations to openness to new ideas). This was not a mandatory training and the participants engaged freely.

The training consisted of a 9-day program spread over several months, where theoretical principles of innovative design (for an overview of the theoretical basis see: Le Masson, Weil [

54]) as well as a large number of theoretical frameworks and methods of creativity and innovation were introduced to the participants so as to allow them to better work on and with novel ideas. The remaining time, approximately 4–5 days of the training, was dedicated to working on pre-defined topics in teams using the tools and methods that were introduced in the training. These topics were specifically chosen because they were all addressing key issues for sustaining the sociotechnical transition Hydro-Québec was facing, such as “energy autonomous communities”, “smart green city”, “0-emission Canada”, “body-generated energy”.

3.3. Data Collection

This paper mobilizes a rich data set from both a focused study of the training program and an extended ethnographic study. By combining extensive observations, formal semi-structured interviews, and more informal and reflective exchanges with actors in the field (see

Table 1 for more details on data sources), we were able to outline the trajectories of four individuals who participated in the training program and who subsequently assumed the role of boundary spanners [

55]. The combination of this data—ranging from the researchers’ observation notes during the training workshops and capturing their first interventions, to the activities and engagements they were initiating a few months later—represented a unique opportunity to analyze boundary spanners in the making.

3.4. Data Analysis

To uncover the characteristics and the process that led several participants in the first training to become boundary spanners, we conducted a three-step analysis. Viewing the participants in the Hydro Quebec training as potential boundary spanners, or boundary spanners in the making, we selected 4 participants from the first cohort (winter of 2015/2016) of training who decided to join the second cohort (fall of 2016) as coaches: Jean-François, Marie-Andrée, Eric and Mariela. These 4 individual trajectories cannot be claimed to represent the trajectories of all the participants in the training; rather, they were selected as illustrative examples of the diverse and multifaceted journeys of individuals who become boundary spanners.

With these 4 individuals in mind, we engaged with our data again to uncover their individual trajectories [

48,

56]. We developed these trajectories by building on their reported interventions, the interviews we had conducted with them, as well as our observational data on their behaviors within different groups and the various initiatives they may have initiated or participated in. We focused on further shaping each trajectory to reach a fine-grained understanding of the characteristics, factors and key events that appeared to influence their behavior and could helped explain how they emerged as boundary spanners.

When the individual trajectory was drafted, we contrasted their trajectories with each other in order to identify a framework of common elements and disparities [

57]. Furthermore, we compared the trajectories and key elements of these individuals with those of other training participants who did not subsequently take on this boundary spanning role. This triangulation using our larger dataset allowed us to confirm as well as invalidate some of our initial assumptions and triggering us to re-work the initial framework, thus reinforcing the validity of our approach [

58]. Ultimately, this process allowed us to distinguish between critical characteristics of boundary spanners in the making, and the contribution that the training program may have played in their development.

4. Accounts from the Field: The Trajectories of Four Boundary Spanners

We introduce here a short account of the trajectories of Jean-François, Marie-Andrée, Éric and Mariela, who have progressively assumed the role of boundary spanners to act as a foundation for our analysis. Based on the experiences of these four individuals, we seek to uncover critical aspects of the process of developing boundary spanners more in-depth, and in particular, how and in what ways the innovative design training program may have contributed to their development as boundary spanners. A summary of essential components in the trajectories is presented in

Appendix A.

Jean-François. Jean-François is a mid-career statistician at the main office of IREQ in the suburb of Montreal, working on electricity demand forecasting using nonlinear regression models. Before the training in 2016, he was already involved in collective activities within IREQ, being, for instance, in charge of organizing an annual meeting of researchers and engineers from within and outside the company regarding the aging of hydroelectric dams. During the first training cohort, he remained a rather discreet participant, asking a few questions regarding the practical applications of the methods presented. During the training workshops, he spent a lot of his time helping his team communicate with each other, as several members of his team came from very different backgrounds and had very strong (and diverse) opinions about the energy sector. At the end of the first training, Jean-François spontaneously started an initiative, called the Innovation Café, to continue sharing ideas and knowledge about innovation methods, as well as the results of exploratory initiatives within the organization. The monthly event has evolved into an internal community that lasted almost a year and brought together more than 18 researchers and managers each time. As the organizer, Jean-François defined with participants the themes established for future sessions, and the presentations were followed by a more open discussion either on the topic of the day or to share news:

“I try to get as much field experience as possible to be able to help and try to circulate information as much as possible. I ended up settling down with our internal virtual sharing tool “GPS”, which is a tool I hate, but I use it and a lot of employees do. I take opinions, I integrate them… I try to create some sharing between the different teams, and project programs. I do it for the benefit of all.”.

(Jean-François, Fall 2016)

Besides setting up the Innovation Café, Jean-François invested a lot of time and effort in challenging the traditional way of setting up of the annual symposium on controlling the aging of assets. He integrated more presentations from people outside the energy industry and gave more space for discussions and workshops, rather than statics presentations. In the fall of 2016, he participated in the second training, not as a participant but as a coach. However, the tension between its new role as a facilitator and connector, and how his work was evaluated by his supervisors led him to decide to focus more on his statistical work. He regretted not being valued for all the aspects of his work, and looked forward to do something else within HQ:

“Research and innovation activities related to asset management (AM) are dispersed throughout IREQ. I am therefore currently working to ensure more synergy between these activities”.

(Jean-François, 2017)

By 2020, Jean-François made some changes in his career, and became Advisor for the Scenarios and Technology Roadmap Team, a unit dedicated to strategic and innovative planning.

Marie-Andrée. Marie-Andrée is researcher in her thirties whose work has been focused on load flexibility and demand response for the electric grid. She works at LTE, a unit of IREQ implanted in Shawinigan, roughly a 1 h drive from the Main Center. The LTE is Quebec leader in the field of technological innovation in the efficient use of energy, and Marie-Andrée is among several researchers who share her expertise. As a participant of the first training, she was joyful and always trying to make everyone at ease during the debates and discussions. Her interest was very much focused on finding quick and efficient ways to implement some elements of the training. From one week to the other, she came back with very specific questions regarding the practical use of the methods and tools presented, and especially the facilitator skills that were required to develop. Quite prone to collaborate with others, she confided that she was looking to reenchant her job after 10 years of doing similar things:

“I started exploration activities with colleagues in the client area. We have set up a series of workshops to identify interesting leads, which will allow us to capture new business models and ways of doing things. I facilitate these workshops with a colleague, so the knowledge I have acquired is directly useful”.

(Marie-Andrée, 2016)

After the first training, she volunteered to set up a workshop with users during a local innovative Fair (C2 Montréal), where she used the tools and methods from the training to invite users to invent new ways to efficiently use energy in their home. Marie-Andrée also supported Jean-François in sustaining the activities of the Innovation Café. She was very keen on developing further her facilitation skills and her capacity to set up ideation and co-design workshops, leading her to become a coach in the second training. Traveling each time from Shawinigan to Montréal to attend the trainings, she committed to help to the best of her abilities her colleagues. In 2020, she is still a researcher at the LTE, involved in all the key projects on new energy uses.

Eric. Eric is a researcher at the LTE unit in Shawinigan, like Marie-Andrée. His research is quite disruptive and novel, focusing on the integration of decentralized energy resources. He is a renowned expert with very specific technical skills. A cheerful team player, Eric arrived one hour early each day of the training, due to his commute and his fear of being late. He then had lots of opportunities to casually discuss with the persons in charge of the training, as well with other participants who would arrive a bit early with a cup of coffee. His interest lied quite a lot with applying the methods to his own research topics, especially regarding mechanisms to foster adhesion from multiple stakeholders to novel and disruptive ideas. When interacting with his team during the workshops, he was on a more observant posture, letting others talk much more, but reorienting the discussions to searching for originality and novelty when the group would settle too quickly on existing ideas. After the first training, Éric used his new facilitation skills to create an exploration group on decentralized energies, identifying and bringing together new groups of people who usually would never work together:

“I really appreciate these new methods which I find very useful. We really improve our brainstorming, and I can more easily identify what is not innovative in terms of ideas to take people further. I have workshops with one of the teams I work with, and I test some of the tools to go faster and map new things in my field.”

(Eric, 2017)

He also dedicated time and efforts to progressively set up field configuring events, such as an annual symposium on decentralized energy resources. Being still in the same position in 2020, as a researcher on the integration of decentralized energy resources, he is recognized as a key resource for setting up ideation workshop, but sometimes feels that it takes a lot of energy:

“Everyone finds it fun to organize and animate the workshops that have been set up, it’s always pleasant because it gives us the freedom to innovate. However, my circle of influence is now too big for me, it stresses me out”.

(Eric, 2017)

Mariela. Mariela is a research scientist and holds a Phd in chemistry. She is conducting research on the development of new materials, and its numerous potential applications to various energy equipment. She works at the main office of IREQ within a multidisciplinary team. She is recognized by her colleagues for her strong technical capabilities and problem-solving skills, but also her dedication and diligence in her work. She was very discreet during the first cohort of training, relying on others to ask questions, but demonstrating clear interest in both the content of the training and its potential applications. Surrounded by more extravert colleagues who were keener on debating and pushing forward their interrogations, she kept her questions for later. Building on her empathy, she cared for the well-being of her team during workshops and made sure everyone was satisfied with the orientations taken. Not a French native speaker, she worked in-between the meetings to make sure she had well understood the technical and sometimes quite abstract concepts that were discussed during the training. Even though language may have been a difficulty to overcome, she was very curious about everything and stayed strongly dedicated to the lectures and workshops, manifesting excitement and enthusiasm in the prospect of applying in real-life settings:

“I’m glad I learned methods to better organize creative work. I’m a chemist so my job is to invent in a laboratory, and the first sessions were difficult, but I loved being in contact with people I didn’t know in the company. I am already trying to mobilize these approaches with teams to reopen the field of research on new materials”.

(Mariela, Fall 2016)

After the end of the training, she set up collective ideation initiatives to explore the potential innovative uses of new polymers in the context of Hydro-Québec. Encountering difficulties in narrowing the scope of the exploration process, she connected with quite different people and went beyond the traditional tasks of her job description.

5. Analysis

While the four trajectories each have their unique and personal qualities, in our analysis we were able to tease out two critical characteristics that appear essential in becoming boundary spanners, and which organizations can strive to identify and encourage: (1) Relevant individual skills and behaviors and (2) Individual knowledge and position. In addition, we explain how and by what means organizations can support and enable the emergence of boundary spanners in practice, exploring more specifically the role that the design training program may have played.

5.1. Critical Characteristics of Boundary Spanners in the Making

Relevant individual skills and behaviors. As organizations seek to encourage and enable individuals to take on boundary spanning roles, the four accounts point to that the role of intrinsic motivation cannot be underestimated, as was clear also from research on individuals in transition processes [

8]. Engaging in boundary spanning activities is not something individuals do because they are told to, but rather because they want to, which supports previous research arguing the informal character of the boundary-spanning role [

11,

59,

60]. For an organization, this implies thinking carefully about what incentives to use to stimulate individuals to dare to explore this kind of role, and that self-selected training programs, possibilities for alternative career paths can be possibilities to do so. Furthermore, while previous research clearly argues that boundary spanners need to have good social skills [

13,

61], our accounts also suggest that boundary spanners need to be team players in order to have the best prerequisites for communicating and integrating knowledge. Organizations thus need to recognize the value of boundary spanners being rooted in a context, and not easily moved from one part of the organization to another. While some research [

12] claims that boundary spanners need a broad but superficial knowledge of the area they are working with, the boundary spanners we saw emerge in our accounts were recognized and respected experts within their respective fields, but with strong T-shaped skills in terms of being able to collaborate across disciplines and apply knowledge outside of their own area of expertise [

11,

62], something that is also essential in transition processes [

5]. Organizations could thus implement, e.g., expert career tracks to encourage individuals to continuously develop and deepen their expertise, while also supporting a breadth of knowledge by combining it with activities and work practices and routines that strengthen the development of T-shaped skills. Finally, we also see that boundary spanners benefit from a high tolerance of ambiguity and ability to take action at their own initiative, which sometimes implies operating in the political sphere of organizations to legitimize and attract resources for specific ideas [

63]. This would also be necessary in the context of sustainable transitions, according to Rotmans and Loorbach [

5]. Still, our accounts suggest that for these individuals, political power-playing was not the main driving force but rather something that needed to be tolerated to be able to experiment and create new knowledge and processes outside of core operations. Organizations can thus benefit from encouraging individual initiative and working in self-managed teams, while at the same time promoting transparency and tolerance of experimentation and failure, to minimize the risk of detrimental political games.

Individual expertise and position. In reflecting about the commonalities of the accounts, we find that while these individuals were certainly recognized experts in their respective field, they were not, however, individual with a very specific, or unique expertise in their organization. Rather, they were supposed to have a generally acceptable depth of expertise (combined with the T-skills discussed above), people who, given the right circumstances, conditions and training, can lead to opportunities to engage in boundary spanning behavior/activities. This is also in line with research on individuals’ role in transition processes, suggesting that deep expertise is not necessarily the most desirable [

5,

8,

11,

14]. Thus, from an organizational point of view, to support the breadth of knowledge there needs to be a sufficient overlap/redundancy in competences, to minimize dependence on specific individuals, or organizing ways to rotate responsibilities/positions to ensure that everyone understands multiple aspects of the work. Additionally, the accounts outline individuals who hold positions that could be considered outside of the core organization, and yet they were able to start new initiatives and secure commitments from others. Their position facilitated operating under the radar, like an invisible hand, making connections and taking initiatives without awaiting approval or direction from the top [

14]. While several of the individuals are contemplating their career choices, it is also clear that they do not seem to be career-driven in how they act. Rather, it appears as if these individuals use their position to engage in boundary spanning activities because they are motivated, interested and see a possibility to do so. To support this, organizations may want to reflect on alternative career paths in the organization and ensure that there are incentives and value in working at each hierarchical level (e.g., not forcing everyone upwards in the hierarchy), or even work towards a compressed hierarchy giving more autonomy and responsibility to groups and individuals to promote intrinsic motivation and encourage initiatives from the bottom.

5.2. How Design Training May Contribute to the Emergence of Boundary Spanners

From our analysis, three outcomes of the training were considered as essential in supporting and enable the emergence of boundary spanners:

Gaining confidence and legitimacy by learning new methods about innovation and creativity. Through the training, participants were exposed to new knowledge, perspectives and techniques for working with innovation and creativity. The setup of the training, which included mixing theoretical input, discussions, practical applications and homework, allowed the participants to gradually become more accustomed and skilled in applying the new methods [

64]. Especially the four participants in focus of our analysis, who participated as team facilitators in the second cohort, were able to develop a more profound understanding as they internalized the knowledge in a new way because they had to coach other participants. Through this successive buildup of competence and knowledge, the four participants could gain confidence in their practice and also legitimacy among their peers, as a new type of “expert” that could act as a boundary spanner [

15,

65].

Experimenting with new and unconventional ideas related to sustainable transitions. Additionally, the training offered multiple opportunities to practice the new methods and experiment with unconventional ideas that were far outside of the daily work, to discuss with peers and learn without the direct involvement of managers. This helped create a sense of psychological safety [

66] in the training community, which supported group learning about sustainability, which, although important, was not considered as core in the organization at that time. In that sense, the training sessions resemble an interstitial space [

67], where individuals are able to temporarily break free from their daily routine and experiment collectively with new activities and ideas, in order to develop new practices. It is suggested that such spaces are fruitful because they are informal and occasional, breaking down silos by serving as a bridge between people with different backgrounds who would otherwise not have worked together. The potential problems or frictions that can arise in such settings can, according to Furnari [

67], be mitigated through the presence of facilitators or catalysts that sustaining others’ interactions and assisting the construction of shared meanings, which is essentially a role played by the 4 participants featured in our analysis. Working in interstitial spaces is thus a valuable experience in the process of becoming a boundary spanner because much of the work of a boundary spanner is to engage others in forming new interstitial spaces.

Developing facilitation skills. Another interesting aspect of the training is the development of the participants as facilitators of creative sessions, which is crucial as boundary spanners need to connect producers and users of knowledge by enabling and organizing their interaction [

11], and this is also considered essential in transition processes [

5]. Initially, many of the participants were uncomfortable with facilitating the exploration of new ideas and engaging in creative processes with others, both internal and external to the organization, as that was not a role or skill that was part of their ordinary jobs. Even at the end of the final training session, many doubted that one day they would be able to apply this skill, which requires practice and cannot be learned just in theory. However, one year later, several of the participants, and in particular the four coaches, pointed out that having gained theoretical knowledge of it and observed how it was done by the facilitators in the training program, they dared to try to put it into practice and gradually develop their facilitation skills:

“I have facilitated exploration sessions with colleagues on several occasions, and the training has helped me to better organize these meetings. (…) I realized that I had to work on them (the sessions) very early to be sure to orient people well and to be able to make them consider different alternatives when they were blocked on a particular aspect or theme.”

(Jean-François, 2017)

This outcome, which was visible only a while after the training was completed, suggests a multifaceted role of the training in offering not only new knowledge and a safe space to experiment and discuss in the moment, but also to showcase and inspire individuals to continuously seek opportunities to apply the newly acquired skills, to increase their willingness to explore unknown territories, and to support self-efficacy in pursuing sustainable innovation. To that end, developing facilitation skills is a critical and necessary part of becoming a boundary spanner.

6. Discussion

Organizations seeking to engage in sustainable transitions must rely on boundary spanners acting as internal change agents with specific skills [

4]. With the aim to facilitate interaction in transition processes, our paper contributes to a better understanding of how such boundary spanners emerge, by identifying and encouraging individual characteristics, and how organizations can work to develop and support boundary spanners, e.g., through a design training program (summarized in

Figure 1). This builds further on the work on differences between boundary spanners, knowledge brokers and gate keepers [

14] and extends current knowledge of the role of training for boundary spanners [

11].

Our contributions are threefold; first, we identify some key individual characteristics to support interactions across system boundaries, to push for the development of new solution spaces and to translate and bring together different groups that are not initially connected, as essential to the emergence of boundary spanners. As such, these boundary spanners are well equipped to act as frontrunners in transition processes [

5,

68]. By clarifying and explicating these key characteristics in terms of relevant individual skills and behaviors and individual expertise and position, we add to the current discussion in transition management literature on what operationalization entails on an individual and organizational level [

1,

4,

14,

69]. While the informal character and emergence of boundary spanners is still heavily reliant on a bottom-up approach, our findings suggest that there are still many things that management can do from the top of an organization to stimulate and encourage individuals to further develop such skills and competences, seek new paths and strengthen their sense of self-efficacy [

70], and ultimately emerge as boundary spanners. For example, top management may consider putting in place specific incentives or recognition mechanisms aimed at acknowledging the work in the shadow often carried out by these actors to connect people, translate knowledge and new ideas to different groups, and develop initiatives that engage the organization towards new ways of doing things, work that often goes unnoticed [

11].

Second—and this is the most central aspect of our study—by adding insights into how a design training program can support the emergence of boundary spanners, we highlight the critical role of organizations to give a dedicated space to individuals to reflect and experiment with new ways to work with other actors [

67], and the value of dedicated training and courses to support these professionals [

11]. It can be argued that perhaps it is not so critical what the topic of the training is (e.g., leadership, social innovation or green business models) but rather that there is a format and the process that allows actors to work hands-on collectively, to explore freely and to quickly put their learning in into action in protected spaces afterwards. As such, our article extends previous work on frontrunners in transition processes [

4,

5] as well as transition arenas [

71,

72] as it opens up a discussion on how such spaces can be created and specifically developing training programs that can be deployed by managers or human resources departments in order to support the emergence of boundary spanners to facilitate and speed up sustainability transition processes.

Our third and final contribution relates to the process of emergence of these boundary spanners and explicating the role of training. Our findings do not suggest that boundary spanners can be made overnight, or even that it happens after a training program is completed. Rather, we have attempted to capture a process, a journey, dependent on both individuals as well as their context, through which individuals have established a learning climate [

9] and become ”primed” to a different way of thinking [

8]; to act as visionaries and frontrunners, with open-minds and the ability to look beyond their own domain to address greater challenges to sustain sociotechnical transitions toward sustainability. Not everyone that took part of the training ultimately emerged as a boundary spanner, but the training still nudged them in that direction. Contributing to recent research on boundary spanners and transition processes [

4,

11,

12,

17,

72], the nuances of the individual accounts of the boundary spanner trajectories have shown that there is a great diversity in who ultimately becomes a boundary spanner, and there is no one-size-fits-all type of boundary spanner. By highlighting that it is a process that relies on both individual behaviors and skills as well as the context and setting around that specific individual, we hope to debunk myths related to specific personality traits (e.g., extroverted or careerist) that suggest that boundary spanners are born and cannot be made.

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Perspectives for Future Research

This paper has explored how organizations can enable individuals to take on boundary spanning roles and develop the skills and competences needed to become boundary spanners needed to drive and implement sustainability transitions. We suggest that organizations can identify and encourage individual skills and behaviors (intrinsically motivated, good social skills, team player, T-shaped skills, high tolerance of ambiguity, ability to take initiative) and individual expertise and organizational position (being recognized experts but not irreplaceable, holding non-core positions in the organization) because these appear important to the emergence of boundary spanners. Furthermore, we propose that the design training program allows the organization to further support the development of boundary spanners because individuals through the training gain confidence and legitimacy by learning new methods about innovation and creativity, can experiment with new and unconventional ideas related to sustainable transitions as well as develop facilitation skills, which is also considered essential to the emergence of boundary spanners. By providing further insights into how boundary spanners emerge and develop, the paper extends previous literature on boundary spanners and operational aspects of sustainability transition processes.

Although our findings are based on a rich qualitative study in a specific context, further research is needed to validate and extend our propositions. While we have focused on a training program specifically around innovative design methods, it does not preclude that other training programs or organizational efforts can also be valuable to the development of boundary spanners. Still, our findings offer a step towards further theory development on the role of individuals in transition processes as well as guide organizations and practitioners in designing new training programs with the purpose of supporting the emergence of boundary spanners.

This research also opens the way to future research. First, it would be interesting to further investigate the organizational mechanisms that may participate in the evaluation and recognition of the roles held by boundary spanners. The informal aspects of facilitating collaboration and the influential roles they can play are often not formally recognized in the evaluation of their performance, although they are crucial in the context of sustainable transitions. Second, it would be interesting to see if other trainings that help create protected spaces for experimenting, collaborating, and developing facilitation skills can contribute to the emergence of boundary spanners. Finally, the literature often highlights the role of intermediary organizations in facilitating the connection and collaboration of different organizations in the context of sustainable transitions, which are thus specialized in boundary-spanning activities. It would be interesting to further investigate the organizational mechanisms that these organizations put in place to cultivate and legitimize the role of boundary spanners both internally and externally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Y., M.A. and R.R.; methodology, A.Y., M.A. and R.R.; data curation, A.Y., M.A. and R.R.; formal analysis, A.Y., M.A. and R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Y., M.A. and R.R.; writing—review and editing, A.Y., M.A. and R.R.; visualization, A.Y., M.A. and R.R.; project administration, A.Y. and M.A.; funding acquisition, A.Y. and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the FRQSC (Grant # 205466) and Chalmers University of Technology, Area of Advance Energy: post-doc grant in 2016.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of HEC Montréal.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary of four illustrative trajectories of boundary spanning individuals.

Table A1.

Summary of four illustrative trajectories of boundary spanning individuals.

| | Jean-François | Marie-Andrée | Mariela | Éric |

|---|

| Job position 2016 vs. 2020 | Research Statistician VS

Advisor, Scenarios and Technology Roadmap Team

Some ambiguity in the trajectory (facilitator vs. business analyst dilemma) | Power Demand Management Researcher vs.

Researcher on new energy use

Not careerist | Researcher in new materials

No change in 2020

Not careerist | Researcher in Integration of Decentralized Energy Resources

(Work in disruption)

No change in 2020

Not careerist |

| Location | IREQ Varennes (Main office) | IREQ Shawinigan (Geographical distance) | IREQ Varennes (Main office) | IREQ Shawinigan (Geographical distance) |

| Social Skills | Very good, Strong Networker

Qualities: Kind, dedicated to the collective | Very good, Medium Networker

Qualities: Team player, committed with a developed empathy. | Very good, but language barrier (French as a second language) Medium-low networker

Qualities: Team player, very emphatic | Very Good, Medium networker at the beginning, strong at the end.

Qualities: team player, committed |

| Expertise | Strong expertise, but not unique at IREQ | Strong expertise, not unique in her initial position at IREQ, much more specialized in her new field. | Speciality with a wide field of application | Critical expertise, difficult to replace |

| Behavior during the first training | Discreet, curious

Wonders about his role in his workshop’s team | Rebounds very quickly and applies the ideas and knowledge that come out of the project.

Committed and seeks early collaboration with trainers | Very discreet

No or very little participation, but a lot of excitement demonstrated at the end of the course | Discreet, curious

Arrives early in the morning, which allows exchanges and reflexivity with the trainers. |

| Key activities taken in charge or facilitated after the first training | Facilitated vision network 2035 (success leading to roadmaps)

Organizing symposium on Asset Management

Initiating community of practice on innovation methods | C2 Montréal: Activity with the client

Initiating community of practice on innovation methods | Leading exploration group on innovative applications of new materials | Leading exploration Group on Decentralized Energy Resources-very active in the organization |

| Motivation to commit to coaching the second cohort | Change profession | Reinvent her career +

Support and facilitate ideation activities | Enhance her scientific expertise + Exploring beyond her domain to see something new | Wanted to disrupt and implement change in his domain |

| Attitude towards organization politics | Conflicted between his expert role and a potential new role in fostering innovative behavior among colleagues | Is content acting under the radar in a unit that has its own culture far from the main office in Montreal | Doesn’t really engage in politics | Is content acting under the radar in a unit that has its own culture far from the main office in Montreal |

References

- Shove, E.; Walker, G. CAUTION! Transitions ahead: Politics, practice, and sustainable transition management. Environ. Plan. A 2007, 39, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schäpke, N.; Omann, I.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Van Steenbergen, F.; Mock, M. Linking transitions to sustainability: A study of the societal effects of transition management. Sustainability 2017, 9, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J. The Dynamics of Transitions: A Socio-Technical Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bögel, P.; Pereverza, K.; Upham, P.; Kordas, O. Linking socio-technical transition studies and organisational change management: Steps towards an integrative, multi-scale heuristic. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmans, J.; Loorbach, D. Transition management: Reflexive governance of societal complexity through searching, learning and experimenting. Manag. Transit. Renew. Energy 2008, 15–46. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1765/37236 (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Lode, M.L.; Te Boveldt, G.; Macharis, C.; Coosemans, T. Application of Multi-Actor Multi-Criteria Analysis for Transition Management in Energy Communities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaa, P.; Kern, F. Creative destruction or mere niche support? Innovation policy mixes for sustainability transitions. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rotmans, J.; Loorbach, D. Complexity and transition management. J. Ind. Ecol. 2009, 13, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Javaid, A.; Javed, A.; Kohda, Y. Exploring the role of boundary spanning towards service ecosystem expansion: A case of careem in pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, P. The competent boundary spanner. Public Adm. 2002, 80, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, K.A.; Sjostrom, K.D.; Vaughan, C.; Nichols, L.; Bednarek, A.; Lemos, M.C. Who are boundary spanners and how can we support them in making knowledge more actionable in sustainability fields? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 42, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keszey, T. Boundary spanners’ knowledge sharing for innovation success in turbulent times. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 1061–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jesiek, B.K.; Mazzurco, A.; Buswell, N.T.; Thompson, J.D. Boundary spanning and engineering: A qualitative systematic review. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 107, 380–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, A. Crowding at the frontier: Boundary spanners, gatekeepers and knowledge brokers. J. Knowl. Manag. 2015, 19, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levina, N.; Vaast, E. The emergence of boundary spanning competence in practice. implications for implementation and use of information systems. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 335–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundurpi, A.; Westman, L.; Luederitz, C.; Burch, S.; Mercado, A. Navigating between adaptation and transformation: How intermediaries support businesses in sustainability transitions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 125366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smink, M.; Negro, S.O.; Niesten, E.; Hekkert, M.P. How mismatching institutional logics hinder niche–regime interaction and how boundary spanners intervene. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 100, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aldrich, H.; Herker, D. Boundary spanning roles and organization structure. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1977, 2, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushman, M.L. Special boundary roles in the innovation process. Adm. Sci. Q. 1977, 22, 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.C.; Cunningham, F.C.; Braithwaite, J. Bridges, brokers and boundary spanners in collaborative networks: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chapple, W.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Welton, R.; Hewitt, M. Lights off, spot on: Carbon literacy training crossing boundaries in the television industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 162, 813–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bednarek, A.; Wyborn, C.; Meyer, R.; Parris, A.; Leith, P.; McGreavy, B.; Ryan, M. Practice at the boundaries: Summary of a workshop of practitioners working at the interfaces science, policy and society for environmental outcomes. Policy Soc. Environ. Outcomes 2016. Available online: https://www.lenfestocean.org/-/media/assets/2016/07/practiceattheboundariessummaryofaworkshopofpractitioners.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Chebrolu, S.P.; Dutta, D. Managing Sustainable Transitions: Institutional Innovations from India. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaa, P.; Bergek, A.; Matschoss, K.; van Lente, H. Intermediaries in Accelerating Transitions: Introduction to the Special Issue; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huxham, C.; Vangen, S. Doing things collaboratively—Realizing the advantage or succumbing to inertia? Organ. Dyn. 2004, 33, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yström, A. Managerial Practices for Open Innovation Collaboration: Authoring the Spaces “in-Between”; Dept. of Technology Management and Economics, Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernández-Chea, R.; Jain, A.; Bocken, N.M.; Gurtoo, A. The Business Model in Sustainability Transitions: A Conceptualization. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Reyes, M.E.; Zwagers, W.A.; Mulder, I.J. Considering the Human-Dimension to Make Sustainable Transitions Actionable. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmans, J.; van Asselt, M.; Anastasi, C.; Greeuw, S.; Mellors, J.; Peters, S.; Rothman, D.; Rijkens, N. Visions for a sustainable Europe. Futures 2000, 32, 809–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevens, F.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Gorissen, L.; Loorbach, D. Urban Transition Labs: Co-creating transformative action for sustainable cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yström, A.; Ollila, S.; Agogué, M.; Coghlan, D. The Role of a Learning Approach in Building an Interorganizational Network Aiming for Collaborative Innovation. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2019, 55, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M.; Ekström, F.; Engeset, A.B.; Aall, C. Transition management: A tool for implementing sustainable tourism scenarios? J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 899–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, M. Boundary spanning for governance of climate change adaptation in cities: Insights from a Dutch urban region. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2018, 36, 837–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, J.; Grin, J.; Hulsink, W. Enriching the multi-level perspective by better understanding agency and challenges associated with interactions across system boundaries. The case of care farming in the Netherlands: Multifunctional agriculture meets health care. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 57, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zietsma, C.; Lawrence, T.B. Institutional work in the transformation of an organizational field: The interplay of boundary work and practice work. Adm. Sci. Q. 2010, 55, 189–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tushman, M.L.; Scanlan, T.J. Boundary spanning individuals: Their role in information transfer and their antecedents. Acad. Manag. J. 1981, 24, 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Ring, P.S.; Van de Ven, A.H. Developmental processes of cooperative interorganizational relationships. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 90–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D. Organizations in Action; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, R.; Suddaby, R. Institutional entrepreneurship in mature fields: The big five accounting firms. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldert, H. Spanning Boundaries Between Policy and Practice: Strategic Urban Planning in Gothenburg, Sweden. Plan. Theory Pract. 2021, 1–17. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14649357.2021.1930120 (accessed on 19 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- Balogun, J.; Gleadle, P.; Hailey, V.H.; Willmott, H. Managing Change Across Boundaries: Boundary-Shaking Practices. Br. J. Manag. 2005, 16, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysonski, S. A boundary theory investigation of the product manager’s role. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosno, J.L.; Rinaldo, S.B.; Black, H.G.; Kelley, S.W. Half full or half empty: The role of optimism in boundary-spanning positions. J. Serv. Res. 2009, 11, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, S.J.; Gallagher, A.J.; Sopinka, N.M.; Nguyen, V.M.; Skubel, R.A.; Hammerschlag, N.; Boon, S.; Young, N.; Danylchuk, A.J. Considerations for Effective Science Communication; Canadian Science Publishing: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Buskey, E.J.; Bundy, M.; Ferner, M.C.; Porter, D.E.; Reay, W.G.; Smith, E.; Trueblood, D. System-wide monitoring program of the National Estuarine Research Reserve system: Research and monitoring to address coastal management issues. In Coastal Ocean Observing Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 392–415. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R.; Ceulemans, K.; Seatter, C.S. Teaching organisational change management for sustainability: Designing and delivering a course at the University of Leeds to better prepare future sustainability change agents. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, A.M. Longitudinal field research on change: Theory and practice. Organ. Sci. 1990, 1, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Siggelkow, N. Persuasion with case studies. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, A.E. Evaluating ethnography: Considerations for analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 1994, 19, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, P.; Hammersley, M. Ethnography and Participant Observation; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Le Masson, P.; Weil, B.; Hatchuel, A. Strategic Management of Innovation and Design; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, A. Strategies for theorizing from process data. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985; Volume 75. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. Triangulation in qualitative research. Companion Qual. Res. 2004, 3, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, A.; O’Malley, L. The role of the boundary spanner in bringing about innovation in cross-sector partnerships. Scand. J. Manag. 2016, 32, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S.; Smart, P. Exploring open innovation practice in firm-nonprofit engagements: A corporate social responsibility perspective. R&D Manag. 2009, 39, 394–409. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, S.D. Self-esteem and the self-censorship of creative ideas. Pers. Rev. 2002, 31, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkan, H.; Spohrer, J. T-shaped innovators: Identifying the right talent to support service innovation. Res. Technol. Manag. 2015, 58, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kislov, R.; Hyde, P.; McDonald, R. New game, old rules? Mechanisms and consequences of legitimation in boundary spanning activities. Organ. Stud. 2017, 38, 1421–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roberts, L.M. Changing faces: Professional image construction in diverse organizational settings. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 685–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Furnari, S. Interstitial spaces: Microinteraction settings and the genesis of new practices between institutional fields. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 439–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaa, P.; Boon, W.; Hyysalo, S.; Klerkx, L. Towards a typology of intermediaries in sustainability transitions: A systematic review and a research agenda. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Rotmans, J. The practice of transition management: Examples and lessons from four distinct cases. Futures 2010, 42, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buuren, A.; Loorbach, D. Policy innovation in isolation? Conditions for policy renewal by transition arenas and pilot projects. Public Manag. Rev. 2009, 11, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, K.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Avelino, F.; Giezen, M. Opening up the transition arena: An analysis of (dis) empowerment of civil society actors in transition management in cities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 145, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valgeirsdottir, D.; Onarheim, B. Studying creativity training programs: A methodological analysis. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2017, 26, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).