There Is No Place like Home! How Willing Are Young Adults to Move to Find a Job?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

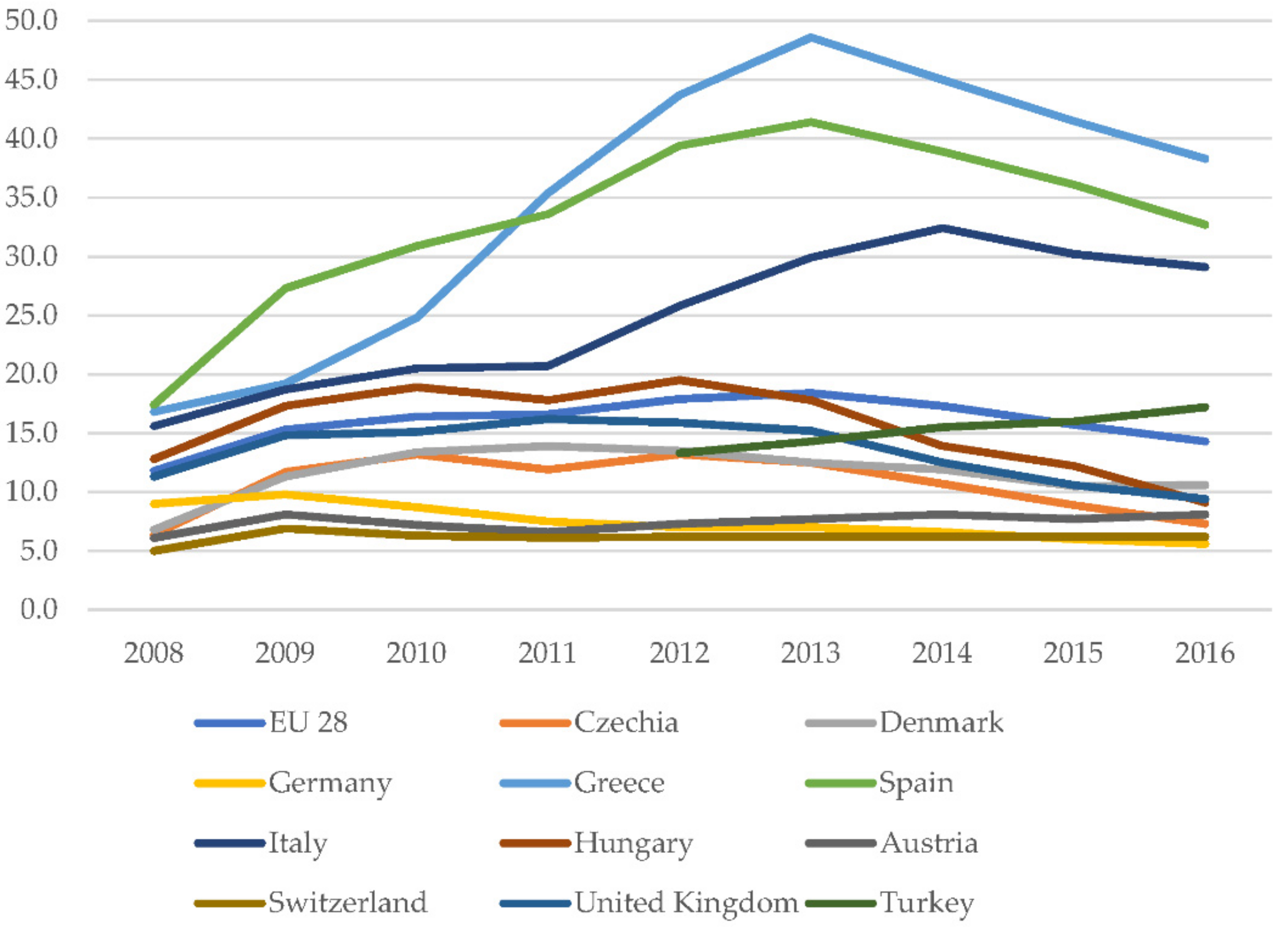

2. Youth Unemployment and the European Agenda to Combat It

3. Young Adults’ Willingness for Job Mobility

4. Data and Method

4.1. Dependent Variables

4.2. Independent Variables

4.3. Control Variables

5. Empirical Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Move within country | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| (2) Move to a different country | 0.443 * | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| (3) Age | −0.093 * | −0.079 * | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (4) Female | −0.072 * | −0.059 * | −0.022 * | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (5) Married | −0.079 * | −0.081 * | 0.354 * | 0.044 * | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (6) Medium education | 0.015 | 0.019 * | −0.242 * | 0.032 * | −0.075* | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (7) High education | 0.069 * | 0.063 * | 0.225 * | −0.003 | −0.024 * | −0.485 * | 1.000 | |||||||

| (8) Risk aversion | 0.127 * | 0.174 * | −0.073 * | −0.103 * | −0.016 * | 0.037 * | −0.004 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (9) Work values | 0.070 * | 0.029 * | 0.007 | −0.037 * | 0.112 * | 0.038 * | −0.081 * | 0.082 * | 1.000 | |||||

| (10) Employment status | −0.044 * | −0.031 * | 0.305 * | −0.161 * | 0.094 * | −0.166 * | 0.181 * | 0.037 * | 0.085 * | 1.000 | ||||

| (11) Economic self-sufficiency | −0.028 * | −0.058 * | −0.000 | −0.055 * | 0.071 * | −0.021 * | 0.093 * | 0.006 | 0.021 * | 0.244 * | 1.000 | |||

| (12) Social ties | 0.082 * | 0.087 * | −0.072 * | 0.040 * | −0.020 * | 0.049 * | −0.070 * | 0.053 * | 0.035 * | −0.221 * | −0.268 * | 1.000 | ||

| (13) Rural index | 0.010 | −0.028 * | −0.018 * | 0.011 | 0.017 * | −0.083 * | −0.051 * | −0.039 * | −0.015 * | −0.062 * | −0.005 | −0.027 * | 1.000 | |

| (14) Familialism | 0.009 | −0.006 | 0.029 * | −0.042 * | 0.155 * | 0.016 * | −0.102 * | 0.059 * | 0.353 * | 0.033 * | −0.030 * | 0.067 * | −0.003 | 1.000 |

Appendix B

| Variable | Question | Range | Mean (Std. Dev.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Move within country | “What changes would you be willing to make to get a new job?” “I would be willing to move to within country”

| 0–1 | 0.41 (0.49) |

| Move to a different country | “What changes would you be willing to make to get a new job?” “I would be willing to move to another country”

| 0–1 | 0.29 (0.46) |

| Age | “How old are you?” (Blank field for respondents to fill in the answer) | 18–35 | 27.16 (4.95) |

| Female | “Are you…”

| 0–1 | 0.52 (0.50) |

| Married | “Which one of the following descriptions best describes your current legal martial status today?”

| 0–1 | 0.29 (0.45) |

| Medium education | “What is the highest level of education you have successfully completed?” Recoded towards:

| 0–1 | 0.21 (0.40) |

| High education | “What is the highest level of education you have successfully completed?” Recoded towards:

| 0–1 | 0.48 (0.50) |

| Employment status | “Which of these descriptions applies to what you have been doing for the last month?” Recoded towards:

| 0–1 | 0.59 (0.49) |

| Economic self-sufficiency | “Thinking about your own financial situation, how satisfied are you right now?”

| 1–4 | 2.46 (0.86) |

| Social ties | “Thinking about your friends, how many of them are unemployed?”

| 1–5 | 2.22 (1.01) |

| Risk aversion | “On a scale from 0 to 10 would you say that in general you are a person who tends to avoid taking risks or are you fully prepared to take risks?” Scale ranging from

| 0–10 | 5.30 (2.40) |

| Work values | “Please read the following statements and tell us how much you agree or disagree with them.” To fully develop your talents you need to have a job. It’s humiliating to receive money without having to work. Work is a duty towards society. Work should always come first even if it means less spare time. For all statements: 1—strongly disagree/2—somewhat disagree/3—somewhat agree/4—strongly agree Recoded towards an index that takes the average of the answers to these statements. | 1–4 | 2.87 (0.60) |

| Familialism | “We would like to know your views about family relationships. To what extent to you agree of disagree with the follwing statements?” It is the duty of family members to take care of each other, even if they have to give up something they want themselves. Family members should stick together, no matter what sacrifices are required. It is important that children respect the decisions made by their parents, even if they disagree with these decisions. For all statements: 1—strongly disagree/2—somewhat disagree/3—somewhat agree/4—strongly agree Recoded towards an index that takes the average of the answers to these statements. | 1–4 | 3.14 (0.60) |

References

- Emilsson, H.; Mozetič, K. Intra-EU youth mobility, human capital and career outcomes: The case of young high-skilled Latvians and Romanians in Sweden. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021, 47, 1811–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aksakal, M.; Schmidt, K. The role of cultural capital in life transitions among young intra-EU movers in Germany. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, F.; Rocca, A.; Rocha, R.; Mateus, C.; Marta, E.; Tosun, J. Time to Get Emotional: Determinants of University Students’ Intention to Return to Rural Areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rye, J.F. Youth migration, rurality and class: A Bourdieusian approach. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2011, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demi, M.A.; McLaughlin, D.K.; Snyder, A.R. Rural Youth Residential Preferences: Understanding the Youth Development—Community Development Nexus. Community Dev. 2009, 40, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodori, A.E.; Theodori, G.L. The influence of community attachments, sense of community, and educational aspirations upon the migration intentions of rural youth in Texas. Community Dev. 2015, 46, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpiña Castillo, C.; Kavalov, B.; Ribeiro Barranco, R.; Diogo, V.; Jacobs-Crisioni, C.; Batista e Silva, F.; Baranzelli, C.; Lavalle, C. Territorial Facts and Trens in the EU Rural Areas within 2015–2030; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, J.; Arco-Tirado, J.L.; Caserta, M.; Cemalcilar, Z.; Freitag, M.; Hörisch, F.; Jensen, C.; Kittel, B.; Littvay, L.; Lukes, M.; et al. Perceived economic self-sufficiency: A country- and generation-comparative approach. Eur. Political Sci. 2019, 18, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Williams, A.M. Editorial Introduction: New European Youth Mobilities. Popul. Space Place 2018, 24, e2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, J.; Eichhorst, W.; Gábos, A.; Hadjivassiliou, K.; Lain, D.; Leschke, J.; McGuinness, S.; Kureková, L.M.; Nazio, T.; Ortlieb, R.; et al. Five Characteristics of Youth Unemployment in Europe: Flexibility, Education, Migration, Family Legacies, and EU Policy. SAGE Open 2015, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eurostat. Youth Unemployment Rate by Sex, Age and Country of Birth [yth_empl_100]. 2021. Available online: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Tosun, J. Promoting youth employment through multi-organizational governance. Public Money Manag. 2017, 37, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmuth, J.R.; Kittel, B.; Steiber, N.; Mühlböck, M. Cultural Pathways to Economic Self-Sufficiency and Entrepreneurship. An Overview of Theoretical Perspectives on Micro Mechanisms. CUPESSE Working Paper 1; Heidelberg University: Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, J.; Hörisch, F. Steering the behaviour of young people: The EU’s policy approach to promote employment. In Research Handbook on Behavioral Change and Public Policy; Strassheim, H., Beck, S., Eds.; Edgar Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 257–271. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, P.; Hörisch, F. Understanding massive youth unemployment during the EU sovereign debt crisis: A configurational study. Comp. Eur. Politics 2020, 18, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Youth in Action. Programme Guide. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012; pp. 1–149. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, J.; Treib, O.; De Francesco, F. The impact of the European Youth Guarantee on active labour market policies: A convergence analysis. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2019, 28, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Youth Employment Initiative (YEI). 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1176 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Council of the European Union. Council Recommendation on a Quality Framework for Traineeships (Employment, Social Policy, Health and Consumer Affairs Council Meeting). Brussels, Belgium. 2014. Available online: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/lsa/141424.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Favell, A. The new face of east-west migration in Europe. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2008, 34, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Commission. Youth on the Move (COM [2010] 477). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. 2010. Available online: http://europa.eu/youthonthemove/docs/communication/youth-on-the-move_EN.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Nienaber, B.; Manafi, I.; Vysotskaya, V.; Roman, M.; Marinescu, D. Challenging youth unemployment through international mobility. J. Soc. Econ. Stat. 2020, 9, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahanec, M.; Zimmermann, K. Labor Migration, EU Enlargement, and the Great Recession; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp, C.; Shore, J.; Tosun, J. Not so risky business? How social policies shape the perceived feasibility of self-employment. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2018, 28, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka, W.; Dudek, M.; Wojewodzic, T.; Król, K. Generational Changes in Agriculture: The Influence of Farm Characteristics and Socio-Economic Factors. Agriculture 2019, 9, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korzenszky, A. Extrafamilial farm succession: An adaptive strategy contributing to the renewal of peasantries in Austria. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 2019, 40, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zmika, K.; Fortes, A.; Tia, M.N.; Sumane, S.; Ayambila, S.N.; Zmija, D.; Satola, L.; Sutherland, L.A. Small farming and generational renewal in the context of food security challenges. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eistrup, M.; Sanches, A.R.; Munoz-Rojas, J.; Correia, T.P. A “Young Farmer Problem”? Opportunities and Constraints for Generational Renewal in Farm Management: An Example from Southern Europe. Land 2019, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kirkpatrick Johnson, M.; Elder, G.H., Jr.; Stern, M. Attachments to Family and Community and the Young Adult Transition of Rural Youth. J. Res. Adolesc. 2005, 15, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjarnason, T.; Thorlindsson, T. Should I stay or should I go? Migration Expectations Among Youth in Icelandic Fishing and Farming Communities. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mol, C. Migration aspirations of European youth in times of crisis. J. Youth Stud. 2016, 19, 1303–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cairns, D.; Growiec, K.; de Almeida Alves, N. Another ‘Missing Middle’? The marginalised Majority of Tertiary-Educated Youth in Portugal during the Economic Crisis. J. Youth Stud. 2014, 17, 1046–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mol, C. Intra-European Student Mobility in International Higher Education Circuits. Europe on the Move; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, C.H. Putting family centre stage: Ties to nonresident family, internal migration, and immobility. Demogr. Res. 2018, 39, 1151–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, M.J.; Dommermuth, L. Internal Migration and the Role of Intergenerational Family Ties and Life Events. J. Marriage Fam. 2020, 82, 1461–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens through the Twenties; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, J.; Speckesser, S.; Jensen, C.; O’Reilly, J. The absorption of structural and investment funds and youth unemployment. In EU Cohesion Policy: Reassessing Performance and Direction; Bachtler, J., Berkowitz, P., Hardy, S., Muravska, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bonoli, G.; Natali, D. The Politics of the New Welfare State; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality, and Behavior; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, G. Expectations, gender, and norms in migration decision-making. Popul. Stud. 2010, 54, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dalen, H.P.; Henkens, K. Explaining Emigration Intentions and Behaviour in the Netherlands, 2005–10. Popul. Stud. 2012, 67, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eurostat. Methodology—Rural Development. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/de/web/rural-development/methodology (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Debus, M.; Stegmaier, M.; Tosun, J. Economic voting under coalition governments: Evidence from Germany. Political Sci. Res. Methods 2014, 2, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J. What is Youth Political Participation? Literature Review on Youth Political Participation and Political Attitudes. Front. Political Sci. 2020, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D.; Kouznetsova, N.; Ray, R.; Ratzlaff, C.; Biehl, M.; Raroque, J. Psychological Culture, Physical Health, and Subjective Well-being. J. Gend. Cult. Health 1999, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbrande, T.; Coppin, L.; van der Hallen, P.; Ester, P.; Fourage, D.; Fasang, A.; Geerdes, S.; Schömann, K. Mobility in Europe. Analysis of the 2005 Eurobarometer Survey on Geographical and Labour Market Mobility; European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions: Luxembourg, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pethe, H. Un-restricted agents? International migration of the highly skilled revisited. Soc. Geogr. Discuss. 2007, 3, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniscia, B.; Deravignone, L.; González-Martín, B.; Pumares, P. Youth mobility and the development of human capital: Is there a Southern European model? J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciano, C. Educational Selectivity in U.S. Immigration: How do Immigrants Compare to Those Left Behind? Demography 2005, 42, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, M.; Arsene, C. The Demographics of Movers and Stayers in the European Union. In Pioneers of European Integration. Citizenship and Mobility in the EU; Recchi, E., Favell, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2009; pp. 26–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cemalcilar, Z.; Jensen, C.; Tosun, J. Gendered Intergenerational Transmission of Work Values? A Country Comparison. ANNALS Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2019, 682, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, D. The mobility imperative for rural youth: The structural, symbolic and non-representational dimensions rural youth mobilities. J. Youth Stud. 2015, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Consequences of Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. The Cosmopolitan Society and Its Enemies. Theory Cult. Soc. 2002, 19, 17–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamonska, J.; Czeranowska, O. Janus-faced mobilities: Motivations for migration among European youth in times of crisis. J. Youth Stud. 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, G.; Bramston, P.; Patrick, J.; Pannach, W. The Relevance of Community Sentiments to Australian Rural Youths’ Intention to Stay in Their Home Communities. Am. Behav. Sci. 2006, 50, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weaver, R.K. Getting People to Behave: Research Lessons for Policy Makers. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.; Hörisch, F. Security or autonomy?—A comparative analysis of work values and labor market policies in different European welfare states. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

| Policy Programme | Policy Measures |

|---|---|

| Youth in Action (2007) | Legal framework for supporting non-formal learning activities of young people (Decision N° 1719/2006/EC). It promotes mobility within and beyond EU borders, non-formal learning, and intercultural dialogue and encourages all young people regardless of their background. |

| Youth on the Move (2010) | Initiative (COM/2016/0940) for improving young adults’ prospects to find a job. The focus is on lifelong learning, higher education, and very centrally on the promotion of mobility. |

| Youth Guarantee (2013) | Commitment by all member states to ensure that youth under the age of 30 receive a good-quality offer of employment, education, apprenticeship or traineeship within four months after leaving education or becoming unemployed. |

| Youth Employment Initiative (2013) | Is one of the main EU financial resources to support the implementation of the Youth Guarantee. It supports young people who are not in education, employment, or training exclusively. |

| European Alliance for Apprenticeships (2014) | Aims to help trainees acquire high-quality work experience under fair conditions and thereby increase their chance of finding a good-quality job. |

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Move within country | 17,406 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Move to a different country | 17,406 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 |

| Rural index | 17,406 | 1.64 | 0.58 | 1 | 3 |

| Age | 17,406 | 27.16 | 4.95 | 18 | 35 |

| Female | 17,406 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Married | 17,406 | 0.29 | 0.45 | 0 | 1 |

| Medium education | 17,406 | 0.21 | 0.40 | 0 | 1 |

| High education | 17,406 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Employment status | 17,406 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Economic self-sufficiency | 17,406 | 2.46 | 0.86 | 1 | 4 |

| Social ties | 17,406 | 2.22 | 1.01 | 1 | 5 |

| Risk aversion | 17,406 | 5.30 | 2.40 | 0 | 10 |

| Work values | 17,406 | 2.87 | 0.60 | 1 | 4 |

| Familialism | 17,406 | 3.14 | 0.60 | 1 | 4 |

| Variable | Move within a Country | Move to a Different Country | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (Obs. 10,217) | Yes (Obs. 7189) | Diff. | No (Obs. 12,294) | Yes (Obs. 5112) | Diff. | |

| Employment status | 0.612 | 0.568 | −0.044 *** | 0.603 | 0.569 | −0.034 *** |

| Economic self-sufficiency | 2.479 | 2.429 | −0.050 *** | 2.49 | 2.381 | −0.108 *** |

| Social ties | 2.145 | 2.315 | 0.170 *** | 2.159 | 2.352 | 0.193 *** |

| Rural index | 1.631 | 1.643 | 0.012 | 1.646 | 1.611 | −0.035 *** |

| Familialism | 3.137 | 3.148 | 0.011 | 3.144 | 3.136 | −0.008 |

| Willingness to Move within the Country | (M0) | (M1) | (M2) | (M3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.971 *** | 0.971 *** | 0.976 *** | 0.971 *** |

| (0.00519) | (0.00517) | (0.00545) | (0.00519) | |

| Female | 0.738 *** | 0.738 *** | 0.720 *** | 0.739 *** |

| (0.0334) | (0.0334) | (0.0329) | (0.0334) | |

| Married | 0.948 | 0.944 | 0.940 | 0.946 |

| (0.0526) | (0.0523) | (0.0523) | (0.0528) | |

| Medium education | 1.282 *** | 1.291 *** | 1.312 *** | 1.284 *** |

| (0.0937) | (0.0940) | (0.0971) | (0.0939) | |

| High education | 1.480 *** | 1.495 *** | 1.554 *** | 1.482 *** |

| (0.0794) | (0.0802) | (0.0839) | (0.0796) | |

| Risk aversion | 1.108 *** | 1.109 *** | 1.109 *** | 1.108 *** |

| (0.0110) | (0.0110) | (0.0110) | (0.0110) | |

| Work values | 1.398 *** | 1.396 *** | 1.403 *** | 1.392 *** |

| (0.0573) | (0.0572) | (0.0579) | (0.0594) | |

| Rural index | 1.185 *** | |||

| (0.0535) | ||||

| Employment status | 0.895 ** | |||

| (0.0476) | ||||

| Economic self-sufficiency | 0.995 | |||

| (0.0284) | ||||

| Social ties | 1.104 *** | |||

| (0.0282) | ||||

| Familialism | 1.015 | |||

| (0.0418) | ||||

| Constant | 0.272 *** | 0.189 *** | 0.208 *** | 0.263 *** |

| (0.0553) | (0.0421) | (0.0471) | (0.0590) | |

| Country fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| AIC | 23,573.18 | 23,551.59 | 23,529.94 | 23,574.93 |

| BIC | 23,712.94 | 23,699.12 | 23,693.00 | 23,722.46 |

| Observations | 17,406 | 17,406 | 17,406 | 17,406 |

| Willingness to Move to Another Country | (M0) | (M1) | (M2) | (M3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.976 *** | 0.976 *** | 0.975 *** | 0.976 *** |

| (0.00552) | (0.00552) | (0.00578) | (0.00552) | |

| Female | 0.801 *** | 0.800 *** | 0.793 *** | 0.799 *** |

| (0.0397) | (0.0396) | (0.0397) | (0.0396) | |

| Married | 0.882 ** | 0.884 ** | 0.889 * | 0.885 ** |

| (0.0541) | (0.0542) | (0.0546) | (0.0544) | |

| Medium education | 1.196 ** | 1.191 ** | 1.231 ** | 1.192 ** |

| (0.0965) | (0.0962) | (0.100) | (0.0964) | |

| High education | 1.489 *** | 1.480 *** | 1.542 *** | 1.485 *** |

| (0.0888) | (0.0885) | (0.0932) | (0.0888) | |

| Risk aversion | 1.169 *** | 1.169 *** | 1.168 *** | 1.170 *** |

| (0.0132) | (0.0132) | (0.0132) | (0.0132) | |

| Work values | 1.183 *** | 1.184 *** | 1.180 *** | 1.194 *** |

| (0.0527) | (0.0527) | (0.0526) | (0.0549) | |

| Rural index | 0.890 ** | |||

| (0.0444) | ||||

| Employment status | 1.053 | |||

| (0.0625) | ||||

| Economic self-sufficiency | 0.918 *** | |||

| (0.0295) | ||||

| Social ties | 1.083 *** | |||

| (0.0309) | ||||

| Familialism | 0.966 | |||

| (0.0424) | ||||

| Constant | 0.192 *** | 0.246 *** | 0.202 *** | 0.208 *** |

| (0.0424) | (0.0606) | (0.0505) | (0.0505) | |

| Country fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| AIC | 20,948.81 | 20,941.53 | 20,915.93 | 20,949.64 |

| BIC | 21,088.57 | 21,089.06 | 21,078.98 | 21,097.16 |

| Observations | 17,406 | 17,406 | 17,406 | 17,406 |

| Willingness to Move within the Country | (M0) | (M1) | (M2) | (M3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.0071 *** | −0.0070 *** | −0.0059 *** | −0.0071 *** |

| (0.0013) | (0.0013) | (0.0014) | (0.0013) | |

| Female | −0.0735 *** | −0.0734 *** | −0.0795 *** | −0.0733 *** |

| (0.0110) | (0.0109) | (0.0111) | (0.0110) | |

| Married | −0.0130 | −0.0139 | −0.0150 | −0.0134 |

| (0.0134) | (0.0134) | (0.0135) | (0.0135) | |

| Medium education | 0.0601 *** | 0.0618 *** | 0.0657 *** | 0.0605 *** |

| (0.0176) | (0.0176) | (0.0178) | (0.0176) | |

| High education | 0.0949 *** | 0.0973 *** | 0.1067 *** | 0.0951 *** |

| (0.0129) | (0.0129) | (0.0129) | (0.0129) | |

| Risk aversion | 0.0248 *** | 0.0250 *** | 0.0250 *** | 0.0248 *** |

| (0.0024) | (0.0024) | (0.0024) | (0.0024) | |

| Work values | 0.0810 *** | 0.0808 *** | 0.0820 *** | 0.0801 *** |

| (0.0099) | (0.0099) | (0.0100) | (0.0103) | |

| Rural index | 0.0411 *** | |||

| (0.0109) | ||||

| Employment status | −0.0268 ** | |||

| (0.0129) | ||||

| Economic self-sufficiency | −0.0011 | |||

| (0.0069) | ||||

| Social ties | 0.0239 *** | |||

| (0.0062) | ||||

| Familialism | 0.0035 | |||

| (0.0100) | ||||

| Country fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 17,406 | 17,406 | 17,406 | 17,406 |

| Willingness to Move to Another Country | (M0) | (M1) | (M2) | (M3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.0050 *** | −0.0050 *** | −0.0051 *** | −0.0050 *** |

| (0.0011) | (0.0011) | (0.0012) | (0.0011) | |

| Female | −0.0449 *** | −0.0451 *** | −0.0467 *** | −0.0453 *** |

| (0.0100) | (0.0100) | (0.0101) | (0.0100) | |

| Married | −0.0254 ** | −0.0250 ** | −0.0238 * | −0.0246 ** |

| (0.0124) | (0.0124) | (0.0124) | (0.0124) | |

| Medium education | 0.0361 ** | 0.0353 ** | 0.0420 ** | 0.0355 ** |

| (0.0162) | (0.0162) | (0.0163) | (0.0162) | |

| High education | 0.0804 *** | 0.0791 *** | 0.0874 *** | 0.0798 *** |

| (0.0118) | (0.0118) | (0.0119) | (0.0118) | |

| Risk aversion | 0.0316 *** | 0.0315 *** | 0.0314 *** | 0.0317 *** |

| (0.0022) | (0.0022) | (0.0022) | (0.0023) | |

| Work values | 0.0339 *** | 0.0341 *** | 0.0334 *** | 0.0358 *** |

| (0.0090) | (0.0090) | (0.0090) | (0.0093) | |

| Rural index | −0.0235 ** | |||

| (0.0101) | ||||

| Employment status | 0.0105 | |||

| (0.0120) | ||||

| Economic self-sufficiency | −0.0173 *** | |||

| (0.0065) | ||||

| Social ties | 0.0161 *** | |||

| (0.0058) | ||||

| Familialism | −0.0070 | |||

| (0.0089) | ||||

| Country fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 17,406 | 17,406 | 17,406 | 17,406 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weiss, J.; Ferrante, L.; Soler-Porta, M. There Is No Place like Home! How Willing Are Young Adults to Move to Find a Job? Sustainability 2021, 13, 7494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137494

Weiss J, Ferrante L, Soler-Porta M. There Is No Place like Home! How Willing Are Young Adults to Move to Find a Job? Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137494

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeiss, Julia, Livio Ferrante, and Mariano Soler-Porta. 2021. "There Is No Place like Home! How Willing Are Young Adults to Move to Find a Job?" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137494

APA StyleWeiss, J., Ferrante, L., & Soler-Porta, M. (2021). There Is No Place like Home! How Willing Are Young Adults to Move to Find a Job? Sustainability, 13(13), 7494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137494