Mindfulness and Next-Generation Members of Family Firms: A Source for Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Development of Hypotheses

2.1. Family Businesses: The Need for Managing Complex and Paradoxical Organizations

2.2. Mindfulness and Family Firms

2.3. Main Benefits of Mindfulness in Organizations

2.4. Drivers of Mindfulness in Potential Successors in Family Firms

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants and Context

3.2. Procedure

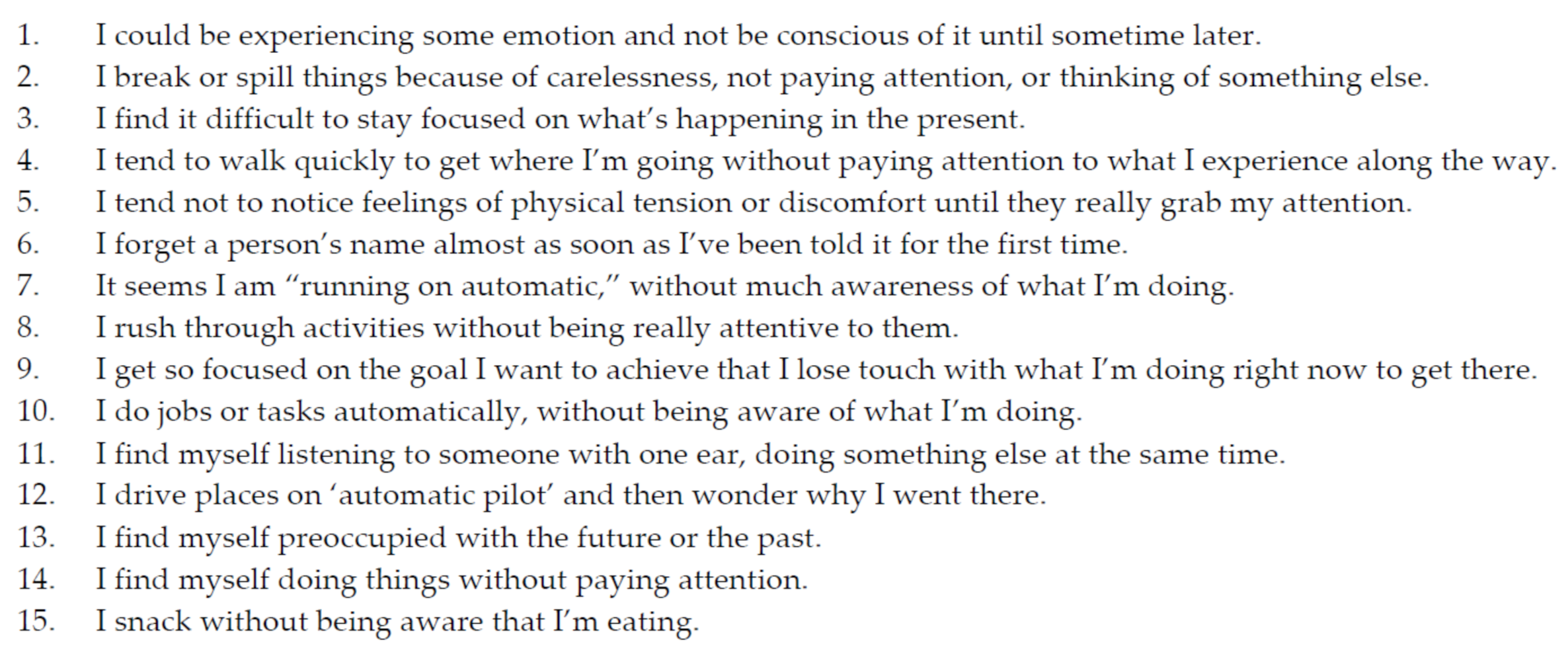

3.3. Instruments and Measures

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory and Descriptive Analysis

4.1.1. Description of the Sample

4.1.2. Mindfulness Level

4.2. Inferential Intergroup Analysis

5. Discussion and Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Helvert-Beugels, J.; Nordqvist, M.; Flören, R. Managing tensions as paradox in CEO succession: The case of nonfamily CEO in a family firm. Int. Small Bus. J. 2020, 38, 211–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Cruz, N.; Barros Contreras, I.; Hernangómez Barahona, J.; Pérez Fernández, H. Parents’ Learning Mechanisms for Family Firm Succession: An Empirical Analysis in Spain through the Lens of the Dynamic Capabilities Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, D.T.; Pearson, A.W.; Payne, G.T.; Sharma, P. Family business research as a boundary-spanning platform. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2018, 31, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudah, M.; Jabeen, F.; Dixon, C. Determinants linked to family business sustainability in the UAE: An AHP approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebl, M.R. Family involvement and organizational ambidexterity in later-generation family businesses: A framework for further investigation. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 1061–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Perlines, F.; Rung-Hoch, N. Sustainable Entrepreneurial Orientation in Family Firms. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine, A.; von Hauff, M. Sustainability-Driven Implementation of Corporate Social Responsibility: Application of the Integrative Sustainability Triangle. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suess-Reyes, J.; Fuetsch, E. The future of family farming: A literature review on innovative, sustainable and succession-oriented strategies. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzubiaga, U.; Maseda, A.; Iturralde, T. Exploratory and exploitative innovation in family businesses: The moderating role of the family firm image and family involvement in top management. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019, 13, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steier, L.P.; Chrisman, J.J.; Chua, J.H. Governance challenges in family businesses and business families. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 1265–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrelli, V.; Rondi, E.; de Massis, A.; Kotlar, J. Generational brokerage: An intersubjective perspective on managing temporal orientations in family firm succession. Strateg. Organ. 2020, 1476127020976972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, G.F.; Batchelor, J.H.; Burch, J.J.; Heller, N.A. Rethinking family business education. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2015, 5, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, M.; Ng, P.Y.; Ndubisi, N.O. Mindfulness, socioemotional wealth, and environmental strategy of family businesses. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.X.; Rooney, D. Addressing unintended ethical challenges of workplace mindfulness: A four-stage mindfulness development model. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Chandwani, R.; Navare, A. How can mindfulness enhance moral reasoning? An examination using business school students. Bus. Ethic- A Eur. Rev. 2018, 27, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Le Breton-Miller, I. Managing for the Long Run: Lessons in Competitive Advantage from Great Family Businesses; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jaskiewicz, P.; Heinrichs, K.; Rau, S.B.; Reay, T. To be or not to be: How family firms manage family and commercial logics in succession. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2016, 40, 781–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, T. Managing the Family Business: Theory and Practice; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pieper, T.M.; Smith, A.D.; Kudlats, J.; Astrachan, J.H. Article Commentary: The Persistence of Multifamily Firms: Founder Imprinting, Simple Rules, and Monitoring Processes. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 1313–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, F.; Melin, L.; Salvato, C.; Seidl, D.; Hitt, M. Call for Papers Special Issue on Advancing Organization Studies in Family Business Research: Exploring the multilevel complexity of family organizations. Organ. Stud. 2015, 36, 1269–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Habbershon, T.G.; Williams, M.; MacMillan, I.C. A unified systems perspective of family firm performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordqvist, M.; Melin, L. Entrepreneurial families and family firms. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 211–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, T.M.; Nason, R.S.; Nordqvist, M.; Brush, C.G. Why do family firms strive for nonfinancial goals? An organizational identity perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irava, W.J.; Moores, K. Clarifying the strategic advantage of familiness: Unbundling its dimensions and highlighting its paradoxes. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2010, 1, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Lewis, M.W. Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 381–403. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, A.E.; Lewis, M.W.; Barton, S.; Gartner, W.B. Paradoxes and innovation in family firms: The role of paradoxical thinking. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2016, 40, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuman, A.; Stutz, S.; Ward, J. Family Business as Paradox; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Waldman, D.A.; Han, Y.L.; Li, X.B. Paradoxical leader behaviors in people management: Antecedents and consequences. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 538–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audebrand, L.K.; Camus, A.; Michaud, V. A mosquito in the classroom: Using the cooperative business model to foster paradoxical thinking in management education. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 41, 216–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandade, K.; Samara, G.; Parada, M.J.; Dawson, A. From family successors to successful business leaders: A qualitative study of how high-quality relationships develop in family businesses. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2020, 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Srinivas Rao, A. Successor attributes in Indian and Canadian family firms: A comparative study. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2000, 13, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, T.M.; Sieger, P.; Halter, F. Should I stay or should I go? Career choice intentions of students with family business background. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cater, I.J.J.; Kidwell, R.E.; Camp, K.M. Successor Team Dynamics in Family Firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2016, 29, 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badham, R.; King, E. Mindfulness at work: A critical re-view. Organization 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Coming to Our Senses: Healing Ourselves and the World through Mindfulness; Hyperion: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, Z.V.; Williams, J.M.G.; Teasdale, J.D. Mindfulness-Bases Cognitive Therapy for Depression: A New Approach to Preventing Relapse; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.M.G.; Teasdale, J.D.; Segal, Z.V.; Kabat-Zinn, J. The Mindful Way through Depression: Freeing Yourself from Chronic Unhappiness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.M.G.; Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness: Diverse Perspectives on Its Meaning. Origin and Applications; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, P.K.; Lee, R.A.; Mills, M.J. Mindfulness at Work: A New Approach to Improving Individual and Organizational Performance. Ind. Org. Psycho. 2015, 8, 576–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, K.M.; Vogus, T.J.; Dane, E. Mindfulness in Organizations: A Cross-Level Review. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2016, 3, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danes, S.M.; Morgan, E.A. Family Business-Owning Couples: An EFT View into Their Unique Conflict Culture. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2004, 26, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labaki, R.; Michael-Tsabari, N.; Zachary, R.K.; Smyrnios, K.; Poutziouris, P.; Goel, S. Emotional dimensions within the family business: Towards a conceptualization. In Handbook of Research on Family Business, 2nd ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Goodman, R.J.; Inzlicht, M. Dispositional mindfulness and the attenuation of neural responses to emotional stimuli. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2012, 8, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, S.R.; Lau, M.; Shapiro, S.; Carlson, L.; Anderson, N.D.; Carmody, J.; Segal, Z.V.; Abbey, S.; Speca, M.; Velting, D.; et al. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2004, 11, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Y. The Influence of Managerial Mindfulness on Innovation: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M.; Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness: Theoretical Foundations and Evidence for its Salutary Effects. Psychol. Inq. 2007, 18, 211–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glomb, T.M.; Duffy, M.K.; Bono, J.E.; Yang, T. Mindfulness at work. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011; Volume 30, pp. 115–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, D.J.; Lyddy, C.J.; Glomb, T.M.; Bono, J.E.; Brown, K.W.; Duffy, M.K.; Baer, R.A.; Brewer, J.A.; Lazar, S.W. Contemplating Mindfulness at Work. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 114–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rubio, D.; Sanabria-Mazo, J.P.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Colomer-Carbonell, A.; Martínez-Brotóns, C.; Solé, S.; Escamilla, C.; Giménez-Fita, E.; Moreno, Y.; Pérez-Aranda, A.; et al. Testing the Intermediary Role of Perceived Stress in the Relationship between Mindfulness and Burnout Subtypes in a Large Sample of Spanish University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reb, J.; Narayanan, J.; Ho, Z.W. Mindfulness at work: Antecedents and consequences of employee awareness and absent-mindedness. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañas, J.J.; Quesada, J.F.; Antoli, A.; Fajardo, I. Cognitive flexibility and adaptability to environmental changes in dynamic complex problem-solving tasks. Ergonomics 2003, 46, 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldao, A.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Schweizer, S. Emotion regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psych. Rev. 2010, 30, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kring, A.M.; Sloan, D.S. Emotion regulation and psychopathology. In Emotion Regulation and Psychopathology: A Conceptual Framework; En, A.M., Kringy, D.S.S., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 13–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J.J. Handbook of Emotion Regulation, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chiswell, H.M. The Importance of Next Generation Farmers: A Conceptual Framework to Bring the Potential Successor into Focus. Geogr. Compass 2014, 8, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, J.H.; Chrisman, J.J.; Sharma, P. Defining the Family Business by Behavior. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1999, 23, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, J.; Tejedor, R.; Feliu, A.; Pascual, J.; Cebolla, A.; Soriano, J.; Pérez, V. Propiedades psicométricas de la versión española de la escala Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). Actas Esp. Psiquiat. 2012, 40, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T.; Lykins, E.; Button, D.; Krietemeyer, J.; Sauer, S.; Walsh, E.; Duggan, D.; Williams, J.M.G. Construct Validity of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in Meditating and Nonmeditating Samples. Assessment 2008, 15, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Irving, P.G. Four Bases of Family Business Successor Commitment: Antecedents and Consequences. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, A.; Minichilli, A.; Amore, M.D.; Brogi, M. The courage to choose! Primogeniture and leadership succession in family firms. Strat. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 2014–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, L.R.; Haynes, K.T.; Núñez-Nickel, M.; Jacobson, K.J.L.; Moyano-Fuentes, J. Socioemotional Wealth and Business Risks in Family-controlled Firms: Evidence from Spanish Olive Oil Mills. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 106–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinthal, D.; Rerup, C. Crossing an Apparent Chasm: Bridging Mindful and Less-Mindful Perspectives on Organizational Learning. Organ. Sci. 2006, 17, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobbs, S.; Raheja, C.G. Internal managerial promotions: Insider incentives and CEO succession. J. Corp. Finance 2012, 18, 1337–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, A.; Calati, R.; Serretti, A. Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | N | Measure | Descriptive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | Mean (S.D.) | |||

| Gender | 190 | Men | 56.8% | (108) |

| Women | 43.2% | (82) | ||

| Age | 193 | Years | 20.07% | (2.38) |

| Degree | 185 | Bus. Admin | 82.7% | (153) |

| Law | 0.5% | (1) | ||

| Bus. Admin + | 14.6% | (27) | ||

| Law | 2.2% | (4) | ||

| Other | ||||

| Variable | Centrality | Variability | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Median | Range (Min./Max.) | S.D. | |

| MAAS 1 | 189 | 4.23 | 4.00 | 1/6 | 1.02 |

| MAAS 2 | 191 | 4.58 | 5.00 | 1/6 | 1.24 |

| MAAS 3 | 192 | 4.23 | 4.00 | 1/6 | 1.14 |

| MAAS 4 | 191 | 3.36 | 3.00 | 1/6 | 1.29 |

| MAAS 5 | 190 | 4.23 | 4.00 | 1/6 | 1.20 |

| MAAS 6 | 191 | 4.31 | 5.00 | 1/6 | 1.47 |

| MAAS 7 | 191 | 4.30 | 4.00 | 2/6 | 1.07 |

| MAAS 8 | 192 | 4.06 | 4.00 | 1/6 | 1.13 |

| MAAS 9 | 191 | 4.21 | 4.00 | 1/6 | 1.08 |

| MAAS 10 | 190 | 2.12 | 4.00 | 1/6 | 1.16 |

| MAAS 11 | 191 | 3.99 | 4.00 | 1/6 | 1.18 |

| MAAS 12 | 190 | 4.93 | 5.00 | 2/6 | 1.24 |

| MAAS 13 | 191 | 4.04 | 4.00 | 1/6 | 1.23 |

| MAAS 14 | 192 | 4.28 | 4.00 | 1/6 | 1.11 |

| MAAS 15 | 192 | 4.55 | 5.00 | 1/6 | 1.41 |

| Men | Women | T-Student | R2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (S.D.) | N | Mean (S.D.) | Value | p | ||

| Mean level of mindfulness | 108 | 4.319 (0.87) | 81 | 4.321 (0.80) | −0.01 | 0.990 *n.s | 0.000 |

| Has F.B. | Does Not Have F.B. | T-Student | R2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (S.D.) | N | Mean (S.D.) | Value | p | ||

| Mean level of mindfulness | 78 | 4.28 (0.87) | 114 | 4.35 (0.81) | −0.61 | 0.541 *n.s | 0.002 |

| 1st Generation | 2nd Generation | 3rd Generation | ANOVA | R2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (S.D.) | N | Mean (S.D.) | N | Mean (S.D.) | Value | Sig. | ||

| Mean level of mindfulness | 34 | 4.19 (0.92) | 25 | 4.46 (0.76) | 16 | 4.28 (0.97) | 0.67 | 0.513 *n.s | 0.018 |

| Wants To | Does Not Want To | Does Not Know | ANOVA | R2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (S.D.) | N | Mean (S.D.) | N | Mean (S.D.) | Value | Sig. | ||

| Mean level of mindfulness | 26 | 4.60 (0.69) | 19 | 4.34 (0.97) | 32 | 3.98 (0.88) | 3.80 | 0.027 * | 0.093 |

| Believe They Will | Believe They Will Not | Do Not Know | ANOVA | R2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (S.D.) | N | Mean (S.D.) | N | Mean (S.D.) | Value | Sig. | ||

| Mean level of mindfulness | 26 | 4.58 (0.77) | 16 | 4.28 (1.03) | 35 | 4.06 (0.83) | 2.72 | 0.027 *n.s | 0.069 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arzubiaga, U.; Plana-Farran, M.; Ros-Morente, A.; Joana, A.; Solé, S. Mindfulness and Next-Generation Members of Family Firms: A Source for Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105380

Arzubiaga U, Plana-Farran M, Ros-Morente A, Joana A, Solé S. Mindfulness and Next-Generation Members of Family Firms: A Source for Sustainability. Sustainability. 2021; 13(10):5380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105380

Chicago/Turabian StyleArzubiaga, Unai, Manel Plana-Farran, Agnès Ros-Morente, Albert Joana, and Sílvia Solé. 2021. "Mindfulness and Next-Generation Members of Family Firms: A Source for Sustainability" Sustainability 13, no. 10: 5380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105380

APA StyleArzubiaga, U., Plana-Farran, M., Ros-Morente, A., Joana, A., & Solé, S. (2021). Mindfulness and Next-Generation Members of Family Firms: A Source for Sustainability. Sustainability, 13(10), 5380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105380