Competitive Pricing of Innovative Products with Consumers’ Social Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Considering consumers’ social learning, how will competitive enterprises set product prices?

- How will the demand and profits of competitive enterprises change with consumers’ social learning?

- How will learning intensity and product quality affect enterprises’ profits under consumers’ social learning?

2. Literature Review

3. Model without Consumer Learning

3.1. Basic Assumptions

3.2. Benchmark Model

4. Model with Consumer Learning

4.1. Process of Consumers’ Social Learning

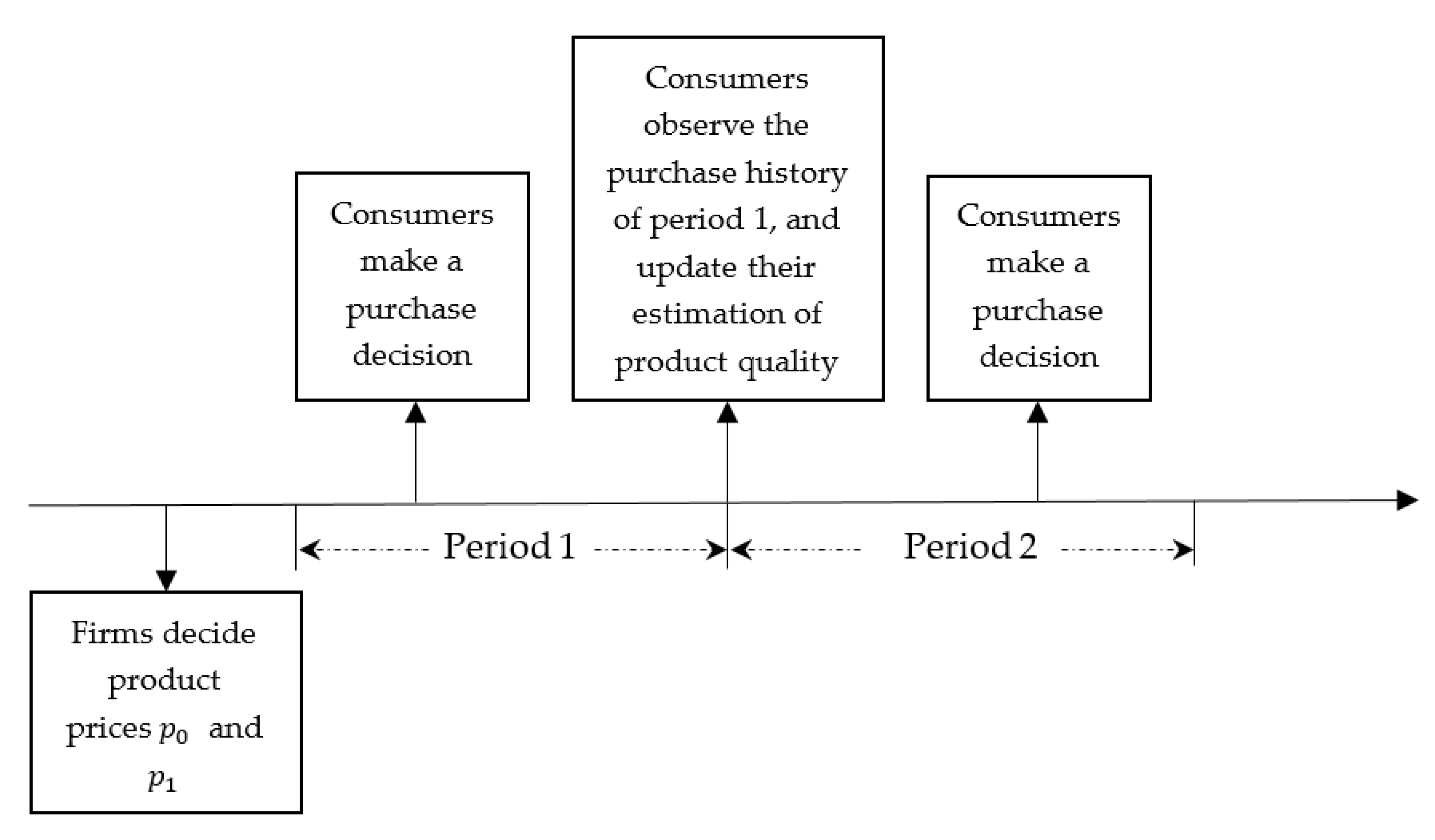

4.2. Decision-Making Process

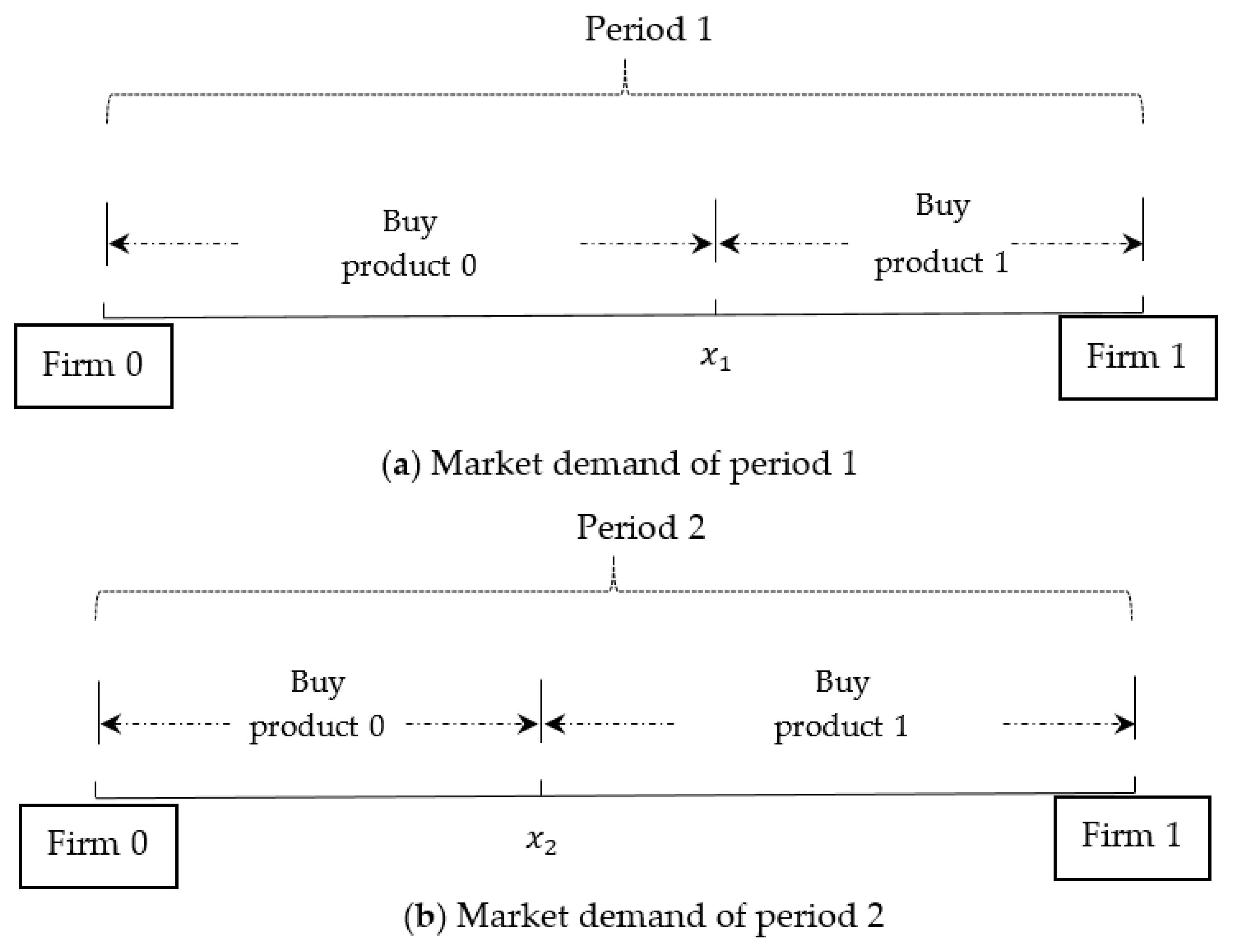

4.3. Equilibrium Analysis

5. Static Comparative Analysis

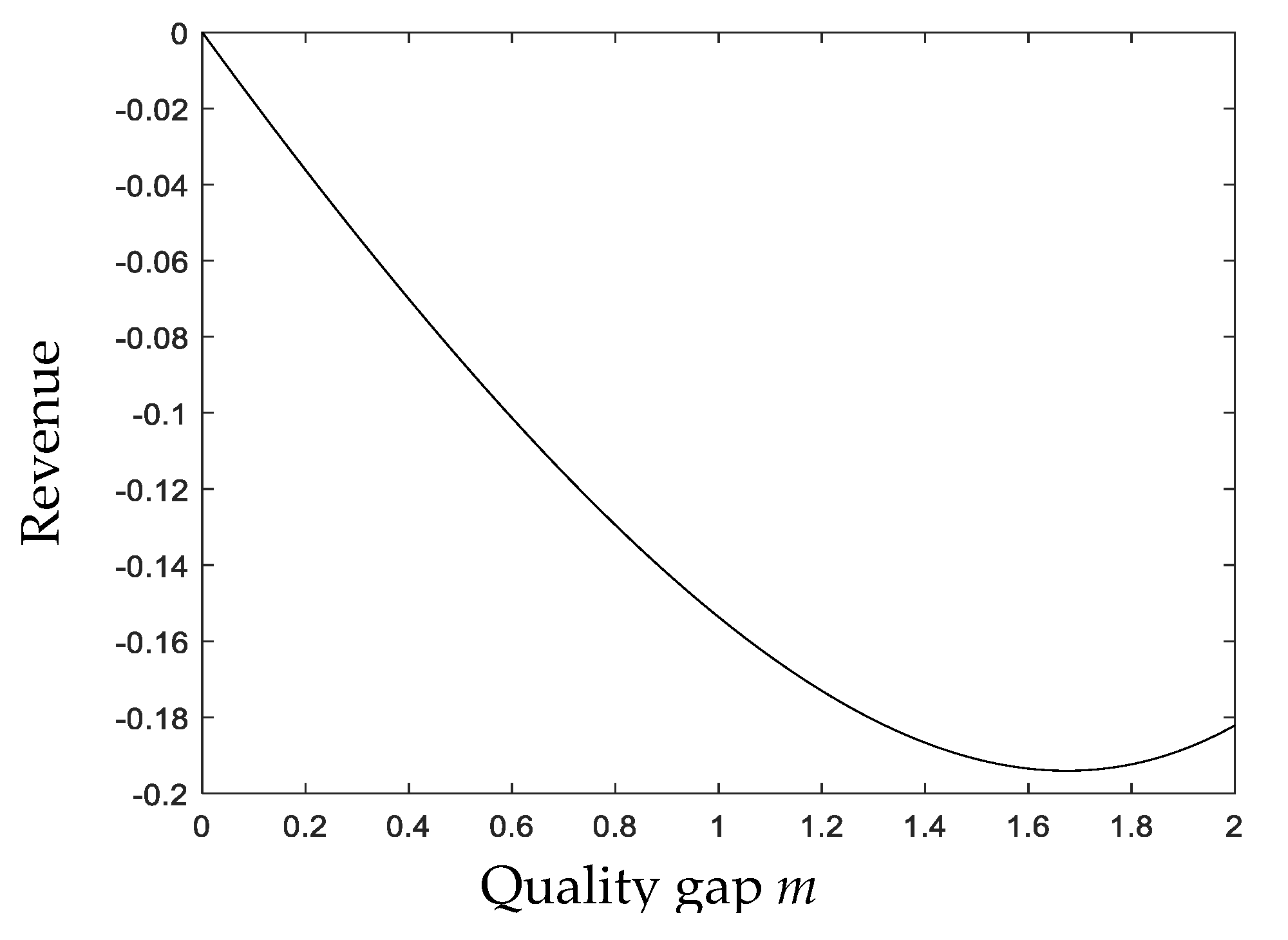

5.1. Effect of Quality Gaps

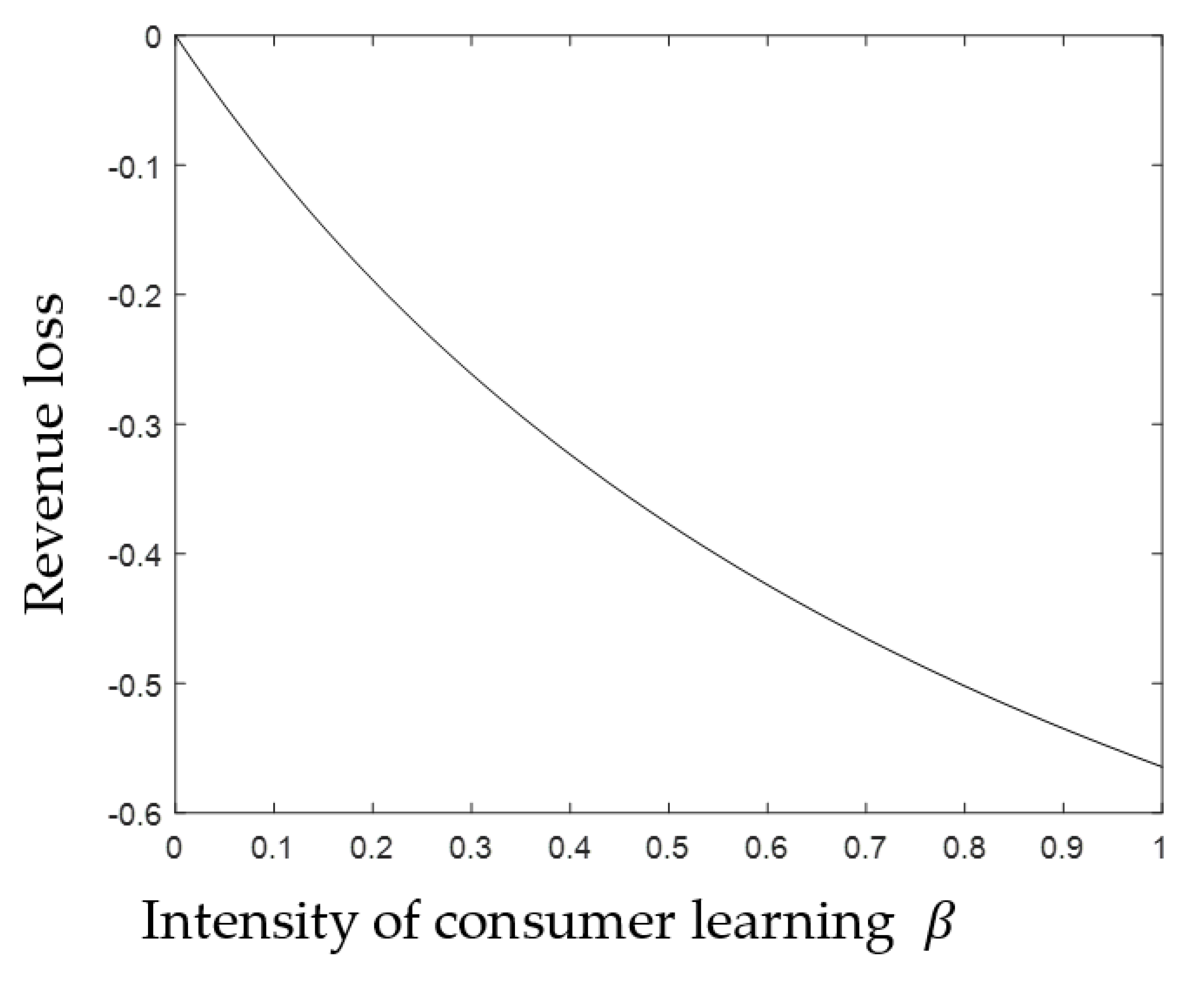

5.2. Effect of Intensity of Consumer Learning

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Zhou, J.; Zhao, X.; Xue, L.; Gargeya, V. Double moral hazard in a supply chain with consumer learning. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 54, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinney, R. Selling to Strategic Consumers when Product Value is Uncertain: The Value of Matching Supply and Demand. Manag. Sci. 2011, 57, 1737–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, P.; Papanastasiou, Y.; Segev, E. Social Learning and the Design of New Experience Goods. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 1502–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.V. A Simple Model of Herd Behavior. Q. J. Econ. 1992, 107, 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Fudenberg, E. Word-of-mouth learning. Games Econ. Behav. 2004, 46, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamley, C.P. Rational Herds: Economic Models of Social Learning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; Volume 8, pp. 265–298. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego, G.; Wang, R.; Ward, J.; Hu, M.; Beltran, J.L. Flexible-Duration Extended Warranties with Dynamic Reliability Learning. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2014, 23, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.D.; Xu, W.; Agrawal, A.; Muthulingam, S. Impact of Bayesian Learning and Externalities on Strategic Investment. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 550–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelen, B.; Kariv, S.; Schotter, A. An Experimental Test of Advice and Social Learning. Manag. Sci. 2010, 56, 1687–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Dahleh, M.; Lobel, I.; Ozdaglar, A. Bayesian Learning in Social Networks. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2011, 78, 1201–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callander, S.; Hörner, J. The wisdom of the minority. J. Econ. Theory 2009, 144, 1421–1439.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. Social learning with endogenous observation. J. Econ. Theory 2016, 166, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Debo, L.; Kapuscinski, R. Strategic Waiting for Consumer-Generated Quality Information: Dynamic Pricing of New Experience Goods. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 410–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzi, N.C.; Dada, M. Dynamic pricing and inventory control with learning. Nav. Res. Logist. 2002, 49, 303–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, U.; Rao, R.C. Leveraging Experienced Consumers to Attract New Consumers: An Equilibrium Analysis of Displaying Deal Sales by Daily Deal Websites. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 3555–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovchinnikov, A.; Milner, J. Revenue Management with End?of?Period Discounts in the Presence of Customer Learning. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2011, 21, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allon, G.; Bassamboo, A. Buying from the Babbling Retailer? The Impact of Availability Information on Customer Behavior. Manag. Sci. 2011, 57, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanastasiou, Y.; Savva, N. Dynamic Pricing in the Presence of Social Learning and Strategic Consumers. Manag. Sci. 2017, 63, 919–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villas-Boas, J.M. Consumer Learning, Brand Loyalty, and Competition. Mark. Sci. 2004, 23, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villas-Boas, J.M. Dynamic Competition with Experience Goods. J. Econ. Manag. Strat. 2006, 15, 37–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergemann, D.; Välimäki, J. Dynamic Pricing of New Experience Goods. J. Polit. Econ. 2006, 114, 713–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, B. Customer Recognition in Experience vs. Inspection Good Markets. Manag. Sci. 2015, 62, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, B. Social Learning and Dynamic Pricing of Durable Goods. Mark. Sci. 2011, 30, 851–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crapis, D.; Ifrach, B.; Maglaras, C.; Scarsini, M. Monopoly Pricing in the Presence of Social Learning. Manag. Sci. 2017, 63, 3586–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, L.; Zhang, H.; Qin, Y. Competitive Pricing of Innovative Products with Consumers’ Social Learning. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093806

Xiao L, Zhang H, Qin Y. Competitive Pricing of Innovative Products with Consumers’ Social Learning. Sustainability. 2020; 12(9):3806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093806

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Lu, Hang Zhang, and Yong Qin. 2020. "Competitive Pricing of Innovative Products with Consumers’ Social Learning" Sustainability 12, no. 9: 3806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093806

APA StyleXiao, L., Zhang, H., & Qin, Y. (2020). Competitive Pricing of Innovative Products with Consumers’ Social Learning. Sustainability, 12(9), 3806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093806