1. Introduction

The current precarious situation of the planet has created the need for the radical transformation of the systems that bring sustainable functioning and governance to societies over the next two decades [

1]. Based on this point of view, higher education—and especially universities as places of innovation, learning and experimentation—have the potential to accelerate transitions towards more just and sustainable societies; however, as institutions deeply rooted in power and privilege, universities also have the potential to reinforce the status quo and resist disruptive changes. A reorientation of higher education towards sustainability requires unconventional ways of looking at management, leadership, knowledge creation, and the interface between science and society. One of the trends that requires this reorientation is the emergence of transition studies towards sustainability.

Definitions from sociology and institutional theory emphasize transitions such as radical transformations of structural and multi-causal characteristics in coevolution as a change in the dominant rules of the game. For Grin et al. [

2], transitions are radical transformations towards a sustainable society in response to the persistent problems faced by modern societies. Rotmans et al. [

3] define transition as a set of connected changes that reinforce each other but are carried out in different areas, such as technology and economics, and the institutional fields that relate to ecology, human behavior, culture, and even belief systems. One approach in transition studies corresponds to sociotechnical systems. This perspective seeks to conceptualize, observe, and influence changes at the system level, integrating research into technological innovation, social sciences, and politics [

4]. Avelino and Wittmayer [

5] state that these changes are the result of the interaction and coordination of actions and innovations across multiple scale levels, highlighting the dynamics of change that result from the tensions between innovation niches and regime [

6]. According to this approach, sustainability converges through the driving forces of multiple actors that deliberately shape transitions around a shared long-term vision [

7].

In general, critical approaches to the transitions of sociotechnical systems focus firstly on emphasizing the relationships between the different actors that are parts of systems. Through this lens we can find forms of analyses that recognize agency and governance as central drivers for influencing system change processes in desirable directions [

8]. The power and empowerment relationships of actors also emphasize the emerging and public/political nature of action and change [

5]. Secondly, scholars have in recent years called for the incorporation of critical perspectives from the social sciences and humanities to transition studies of sociotechnical systems [

9,

10]. These approaches include just transitions to sustainability, a concept that, while still lacking consensus from scholars, incorporates a number of principles related to the effective participation of the constantly marginalized and oppressed sectors of society (women, indigenous communities, etc.), greater diversity in the system’s governance, and greater equity in the benefits resulting from these transformative processes [

11]. Indeed, new approaches to just transitions towards sustainability are established when we consider that the poorest populations on the planet have contributed the least to our current crisis, yet they are in the greatest state of vulnerability to the disastrous effects of climate change.

To achieve this change, it is essential to understand the magnitude and depth of the transformations, as well as the complexity of the social, technological, and ecological transitions required in the formal, informal, and policy-making spheres [

12]. From an educational perspective, it is necessary to overcome the current hegemonic pedagogical model that impedes the development of critical thinking (CT). Its origin dates back to the industrial era, although its epistemological bases are anchored in the nineteenth century, and it is characterized by a fragmented curriculum, a methodology that proposes that all students learn in the same way, a pedagogy that is understood as a mere unidirectional transmission of information from the teacher to the student, and an organization of the space, time, and grouping of students in a way that is totally out of step with today’s new learning approaches [

13].

Recognizing that it is impossible to deny, except intentionally or through innocence, the political aspect of education [

14] and its importance in the structures of the systems that govern us, the contribution of critical thinking in the field of education for development (ED) has been examined. It was in 1974 that, for the first time, an international agency such as UNESCO urged governments and all organizations engaged in educational activity among young people and adults to consider education as a means to help solve “the fundamental problems that impact the survival and well-being of humanity—inequality, injustice, and international relations based on the use of force—and to put in place measures that can facilitate their solution” [

15]. Since then, with the evolution of ED, we can distinguish five generations according to the advances observed in their approaches, content, and practices: the charitable-assistance approach, the developmental approach, critical and supportive development education, education for human and sustainable development, and education for development for global citizenship [

16,

17].

This evolution of ED has been linked both to the evolution of education and the evolution that the concept of development itself has undergone [

18]:

From a development perspective: in the 1950s, ED conceived the concept of development as a process resulting from the transfer of resources. It now conceives it as a multidimensional process of transformations aimed at generating capacities and opportunities for humanity [

19], as well as promoting a conscious and committed global citizenship.

From an educational perspective: ED is a dynamic concept, which is not conceived as a one-off aspect of the curriculum or a formative activity, but it is “a pedagogical line linked to intercultural education, under the focus of human rights and the culture of peace” [

20].

Lately, ED has been equipped with new content which facilitates the critical understanding of the globalization model and re-affirms the link between development, justice, and equity. In addition, ED should promote a global citizenship awareness linked to the issue of co-responsibility and oriented to local and global involvement and action. Similarly, ED strategically takes the “developing gender” approach to overcoming gender inequalities and injustices [

17]. This approach seeks to understand and analyze the functions and roles assigned by gender in social, political, and cultural circumstances. It is in this context that several authors have suggested that the capacity for critical thinking represents one of the fundamental skills to cultivate humanity within the field of education [

21] in the twenty-first century [

22].

It is in this generation that we find Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), understood, according to UNESCO [

23], as a holistic and transformative education that addresses the content and learning outcomes as well as the pedagogy and learning environment. As a result, ESD not only integrates content such as climate change, poverty, and sustainable consumption into curricula, but also creates interactive, student-centered teaching and learning contexts. What ESD requires is an evolution from teaching to learning. It seeks transformative and action-oriented pedagogy, and is characterized by aspects such as self-taught learning, participation and collaboration, problem orientation, inter- and trans-disciplinarity, and the creation of links between formal and informal learning. Only such pedagogical approaches can enable the development of the key skills needed to promote sustainable development [

23].

In general terms, two main streams of analysis that link critical thinking and education to sustainable development can be identified. First, empirical approaches and studies related to critical thinking and its implication, value, and usefulness with regard to people’s decision-making and actions towards sustainable development. This approach emphasizes the role that critical thinking plays as a fundamental skill, competence, and attitude for the development of sustainable awareness [

24], to analyze reality more effectively [

25] or as an element that allows people to reflect on their own actions [

26]. The second line of critical thinking emphasizes the strategies and methodologies used in higher education to incorporate, strengthen, evaluate, and transfer knowledge of sustainability towards the personal and professional development of students, using case studies [

27] or experiential learning [

28,

29] to represent alternatives for which there is growing interest in the academic field.

Furthermore, the use of new approaches in education allows for the development of critical thinking. This is the case for project-based learning (PBL) which helps participants to apply their knowledge to real social problems. PBL confronts students with authentic problems similar to real work activities, and it helps to develop soft skills, such as teamwork and collaboration, communication, critical thinking, and creativity, among others [

30]. PBL theory is founded on experiential learning [

31], inquiry-based learning [

32], and constructivist theory [

33]. PBL proposes from the beginning the obtaining of a concrete solution for a problem [

34]. PBL is a pedagogical approach focused on the acquisition of skills to understand large-scale and systemic change, particularly in its interactions with social movements. It is oriented towards collective social action and innovation, considered key drivers for the transition to sustainability [

4]. According to Jensen [

35], collective social action is defined as a voluntary action taken in common by a group of actors pursuing a shared interest. For this reason, good training in critical thinking must always be oriented towards action, that is to say, towards problem solving, in order to achieve personal and social satisfaction or happiness [

36].

Multiple examples in different fields [

37,

38,

39] have already studied the implications of PBL in the development of critical thinking. Moreover, the authors of [

40,

41] analyze quantitatively the development of CT in different pedagogical initiatives. Their main findings are that PBL is an effective tool for critical and creative thinking. Furthermore, introducing a collaborative pedagogical methodology in PBL stimulates the cognitive, motor, ethical, and affective aspects of learning. The students, as investigators, are turned into agents generating the knowledge that they learn. Whilst statistical methods might provide valuable evidence of these trends among learners, qualitative analysis addresses how and why these trends occur and what they mean for those taking part in critical thinking-based research. In that sense, it is in our interest to deeply understand how student reflections around engagement with a real problem, and how this is linked to a transition towards sustainability, combined with proposed didactic methods, can act as catalysts for critical thinking that supports sustainable development.

The purpose of this paper is to contribute to the latest stream of studies regarding critical thinking and its relationship to education for sustainable development through the results of a PBL experience developed during the Research Methodologies course of the Master’s in Local Development and International Cooperation at the Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV). An action research (AR) project was proposed between a group of twenty-two students and the farmers of the Agroecological Market (AM) at UPV. During the PBL, the students reflected individually and collectively on their actions using different techniques, thoughts, and judgements that characterized their critical thinking. These reflections were subsequently analyzed through the use of qualitative analysis techniques to identify the presence of critical thinking in the outcomes generated by students during the pedagogical process. Therefore, the main objective of the paper was to analyze the contribution of PBL to students’ critical thinking and its relationship with sustainable development through a qualitative analysis of the pedagogical outputs obtained during the process.

The structure of the paper begins with the theoretical framework that will allow for the examination of the categories of critical thinking identified in this research and their relationships with education for sustainability. Secondly, we present the project-based learning experience based on an action research methodology. Finally, the development of the students’ critical thinking is analyzed in detail, concluding with some reflections on the whole process.

3. A Project-Based Learning Experience

3.1. The UPV’s Agroecological Market (AM)

Every Thursday, local farmers come to sell their products at UPV’s Agroecological Market, originally promoted by social organizations based at the university, but currently managed directly by the UPV. In this Agroecological Market, local products are prioritized, with social and solidarity economy certifications. Currently, the market has ten farmers with a wide variety of products.

The AM is a young project, in that, little by little, it is being accepted by the campus community, and farmer’s sales have been increasing over the last three years. It has four main objectives: (i) to raise awareness of the importance of responsible consumption; (ii) to offer the university community a direct sales service for agroecological products; (iii) to strengthen incipient experiences linked to agroecology and food sovereignty; and (iv) to connect the scientific and educational potential of the UPV with the social network of the rural area surrounding the city of Valencia.

Currently, the AM is held every Thursday during the academic year at the Agora campus Vera, from 9.30 a.m. to 14.00 p.m. The weekly offer includes vegetables, fruits, cheese, bread, nuts, legumes, honey, and beverages. In addition, a variety of fair-trade entities in the city of Valencia have a regular presence in the AM. All products must have a seal from a participatory guarantee system (PGS) [

60] or at least the official ecological certification, prioritizing local, seasonal products and involving people in the achievement of food sovereignty.

The identity of the AM is defined using key concepts such as: awareness, proximity, opening, multiplier effect, balance and visibility. Moreover, AM farmers collectively define their aspiration as:

An Agroecological Market with certain stability (weekly), that is dynamic and proposes other activities, open to the outside, with an economic sustainability for the farmers, that opens the market with more positions and higher technology, which is linked to educational activities and that generates synergies with the different schools of the UPV and with the services of these schools.

Finally, the main actions to achieve this aspiration are: institutional dissemination, outreach to other campuses or neighborhoods, weekly market, collaboration with the campus’ cafeterias, proposing student projects related to the Agroecological Market.

3.2. The Master’s Degree in International Cooperation

The Research Methodologies (RM) course of the Master’s degree in International Cooperation at the UPV studied here consisted exclusively of an action research project which aimed to introduce students to research concepts and techniques through a PBL experience. The use of this approach faced great challenges related to engaging the students for three months in a long project with several uncertainties, but also gave rise to many opportunities to introduce a real research project into the course and to adapt the concepts taught in class to the necessities of the process.

During the academic period in which this research was carried out (2018–2019), a total of 22 students participated (14 females, 8 males). Eighteen came from various provinces in Spain, 2 from Colombia and 2 from Chile. The ages ranged from 25–31 (18 students) and 38–42 (4 students). The academic level comprised predominantly the Bachelor’s degree (20 students), with only 2 students holding a Master’s degree at the time of the course. The previous academic backgrounds of the students were in engineering (6 students), humanities and social sciences (7 students), biological sciences (4 students), and administration (5 students).

A central feature of the Master’s degree has been its focus on offering training oriented to what is defined by Clarke and Oswald [

61] as a critical development practice. This practice is characterized by placing the principles of social justice at the center of values and practices, and assuming the complex and political nature of development processes, which are understood to be permeated by power relations [

61]. This approach is related to the concept of professional skills developed by Walker et al. [

62], in which they propose that a university committed to human development and poverty reduction must address the training of development professionals from the perspective of their contribution to social change.

This set of imperatives leads us to consider that, beyond learning the essential techniques of development project management, it is also essential to work on the capacity to adapt to a changing, complex and non-conflict environment, and to be able to handle it. Therefore, this approach is about “being able to operate within the inherent complexity and unpredictability of social systems” [

63], being able to “deal better with complexity—not controlling it, but acting consciously and with resolution” [

64].

Along these lines, the Master’s degree is about building action-oriented critical learning within the framework of training related to development projects. To do this, the program incorporates the Brookfield approaches to CT [

65] in several aspects. On one hand, we highlight confrontation and the questioning of the hegemonic values, ideas, and practices in the field of development to assess their implications in terms of power relations between the actors involved in the processes. On the other, we highlight reasoning and analysis skills to form proper judgments of a rigorous nature, knowing how to contrast points of view based on available information. Finally, we emphasize learning to build and deconstruct their own experiences and meanings in complex intercultural contexts to enable action aimed at promoting changes of a social nature.

This course, developed within the RM module, used PBL as a methodological basis to design an action research project linked to the UPV’s Agroecological Market. This framework departs from the point of view of classical research approaches. It is based on experiential learning and focuses on solving real-world problems. The framework is collaborative and participatory and offers the possibility that participants gain a deeper knowledge of the problem at hand, making sense of it, asking good questions, and developing new ideas and solutions.

The methodology proposed in the course is based on an action research (AR) approach following the ideas of popular education by Freire [

66] and social research from the end of the twentieth century. The social groups who participate define the research questions, partake in the different phases of the project, and empower themselves with the results for their action and dissemination.

The first conceptualizations of AR are attributed to Kurt Lewin in the 1940s in the United States, constituting what Kemmis and McTaggart [

67] call the first generation of AR. Kurt Lewin defined AR as a participatory and democratic process carried out with the participation of the local population itself through all phases of the research: information gathering, analysis, conceptualization, planning, execution, and evaluation. This proposal argued that theoretical, practical, and social changes could be achieved simultaneously [

68]; as Lewin stated, “No action without investigation, no investigation without action” [

69].

A new generation of AR emerged within the social movements of developing countries [

70], supported by Popular Education Theories. In this sense, this new approach proposes the elaboration of theoretical arguments to justify more active approaches, and the need for AR to link its activity to broader social movements [

71].

For the purposes of our course and this study, we define AR as a process that includes study, reflection, and action. This process seeks to obtain reliable and useful results to improve collective situations that positively affect the rest of society. AR is based on the participation of social groups in the research process, which change from being the “object” of study to be the main subject of the research, controlling and interacting throughout the investigative process.

AR and CT are intimately related, as we have stated in our definition of action research. This has also been observed in other AR processes [

71,

72]. For this reason, CT is defined as a transversal competence in RM. Moreover, pedagogically its incorporation is implicit in the AR process.

3.3. The Project-Based Learning Process

To begin the project process, farmers selected a spokesperson to represent the collective. This person was the contact who channeled all information between students and farmers. The methodology used was based on AR and is defined in

Table 1.

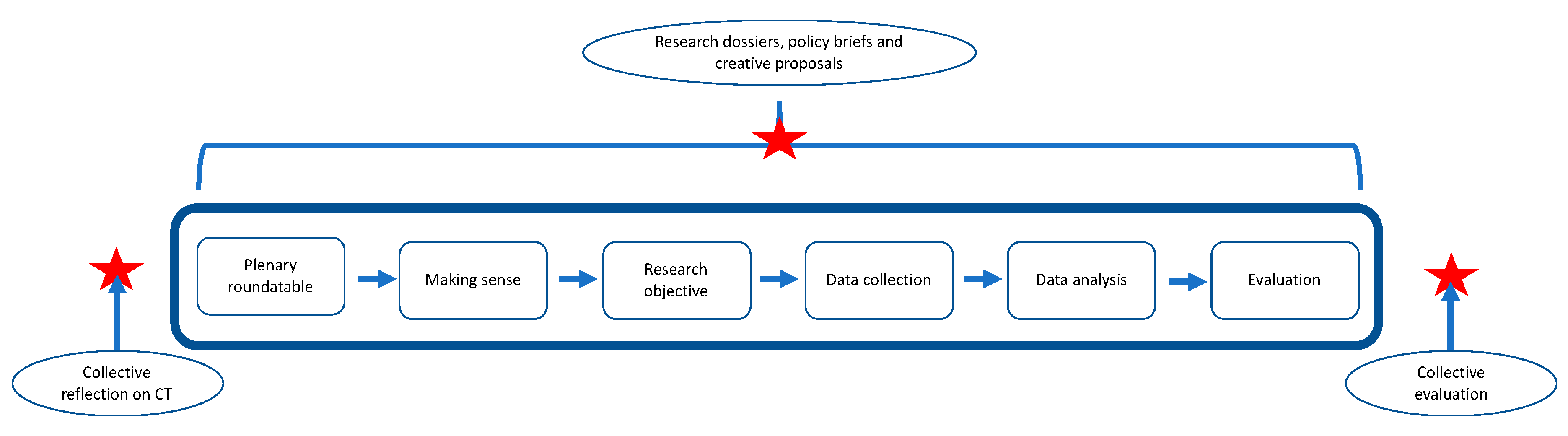

In

Figure 1, the scheme of the project-based learning process is presented, including the action research plan, along with the results produced by the students and the collective sessions carried out with the students to discuss their initial views and opinions and their final learnings and reflections.

3.3.1. Understanding the Context and Defining the Objective

The first step for the students participating in the action research process was to define the situation of the AM, and the demands and concerns of the farmers/vendors. A plenary roundtable was organized with the participation of four active members of the AM. The history, structure, organization, and problems of the AM which have made it difficult over time to achieve the AM’s objectives were presented. This stage was essential, because, aside from introducing the students to the members of the AM, it allowed students to establish their baseline data. Their understanding, explicit in their models using Lego® Serious Play®, was validated with the AM through their spokesperson.

This roundtable with farmers from the AM lasted for two hours and offered different information and visions. In the end, the students concluded that there were a variety of problems that could be solved to achieve the AM’s goals. Some of the problems they discovered included:

The price of the products, which does not adjust to the purchasing power of the students;

The day and time that the AM is held;

The low visibility that the market has among students at the university campus;

The AM has to be profitable in order for the farmers to come to the market.

The second step was to analyze the information garnered from the roundtable and make sense of it. The students were divided in two groups, each of 11 people. Ideas, questions, and objectives were analyzed using the methodological tools of Lego

® Serious Play

® based on the problems expressed by the farmers in the previous stage. Lego

® Serious Play

® is a methodology to facilitate communication not only orally but also through visual and tactile practices. It multiplies the collective reflection and understanding of complex ideas. The method helps to: i) use metaphors to explain ideas, making them more easily understood by others; ii) learn how to arrive at consensus solutions without the need for lengthy discussions or giving up firm beliefs; iii) learn the importance of developing general principles for making decisions rather than having to follow a list of instructions [

54]. The organization of small groups, which is recommended in Lego

® Serious Play

®, allowed all the students to participate actively and have their points of view considered. This strategy permits the use of this technique with larger groups of students divided in small groups, which can enrich the analysis through including each student’s own interpretation of the project’s context.

In our case, the main role of Lego

® Serious Play

® was as a catalyst for developing a collective narrative of the current and the aspirational context of the AM. Moreover, it is important to note that Lego

® Serious Play

® is not a problem-solving technique. Its purpose is related to collectively reflecting on the most important features of a context. This technique allowed the students to interpret and elaborate the initial information provided by the farmers and relate it to the theoretical background studied in the other courses in the International Cooperation Master’s degree. The technique began with an individual model which was shared by the participants. After this first step, the students selected the most important element of their models, and, by combining these elements across the groups, they built a shared model depicting a story that was agreed upon by all the participants. In this sense, the description of the AM´s context and the related theoretical background were agreed collectively upon following a process of respecting each of the individual contributions (

Figure 2).

The context analyzed by the students identified that there is little visibility of the market outside of the campus. Within the campus, the analysis established that consumers perceive difficulties regarding the price of the product as well as a lack of knowledge about sustainable consumption. Moreover, farmers do not have enough information about the campus and its population, and they observe that there is a lack of coordination among the farmers themselves.

After the contextual analysis, the students envisaged a future AM which met the objectives set by the farmers. They understood that farmers should have an impact in the consumption habits of the campus population. In addition, the farmers should become better known through improved marketing mechanisms. Similarly, agreements could be made with the university agents that exist within the campus itself, such as restaurants or catering services, that could offer other ways of doing business for the farmers.

Next, students discussed the theoretical framework for carrying out this study. Some of the chosen theories were: (i) transitions towards sustainability; (ii) solidarity economy; (iii) social communication; and (iv) ecofeminism. All these topics were used afterwards in explaining the results and proposals in the composition of the policy brief research dossiers.

The consensus research question was validated by the farmers in a meeting between spokespersons representing both students and farmers. They agreed on the research question of: What is the degree of knowledge of the UPV’s Agroecological Market and the kind of consumption [behaviors] of the students at the UPV’s campus?

3.3.2. Gathering and Analyzing Data

Data was gathered by means of quantitative (survey) and qualitative (interviews, focus group, and participant observation) techniques. This was carried out based on the contents given in the successive theoretical classes, such as the type of research, paradigm, theoretical framework, logic, form of study, and methodology.

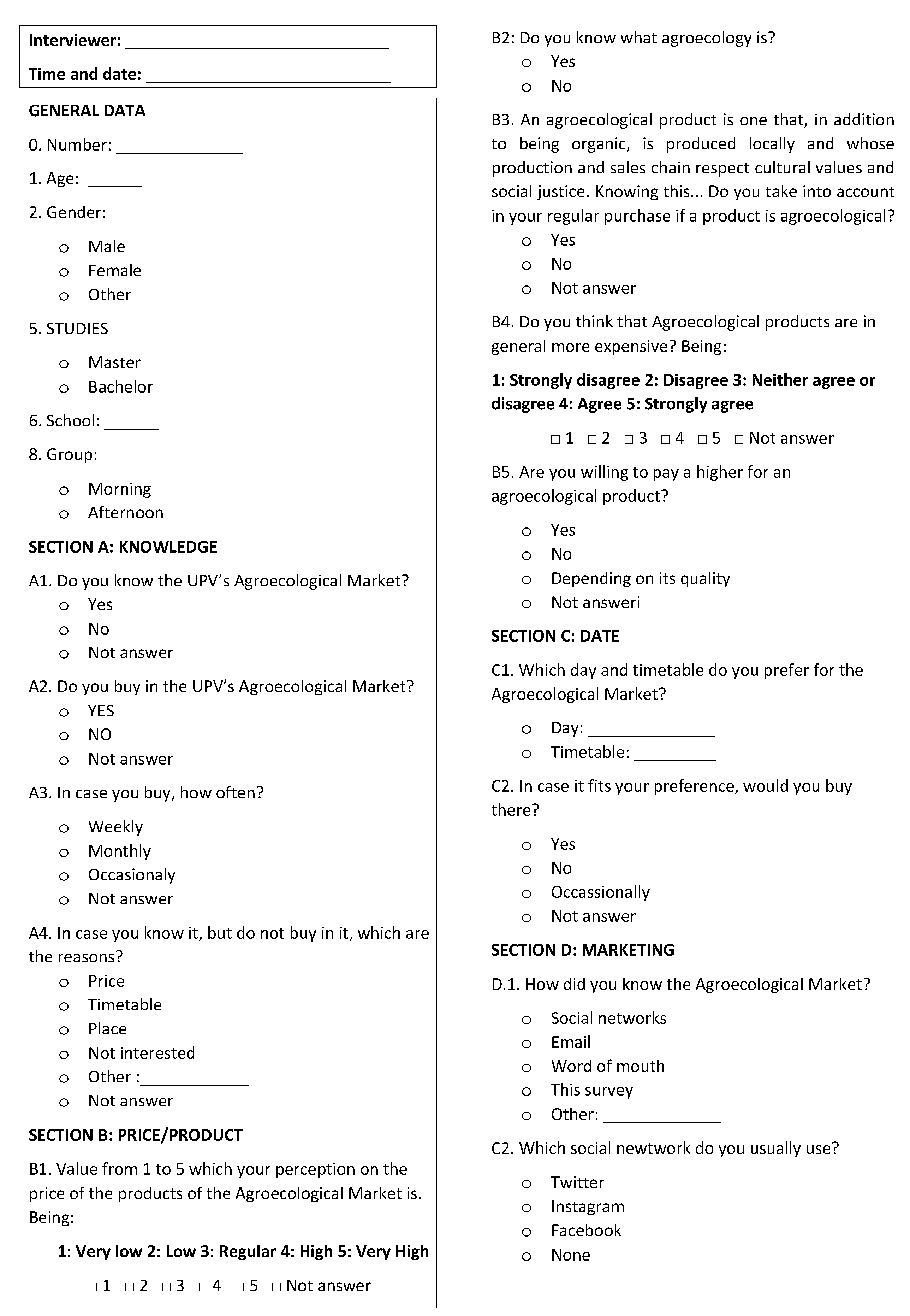

The objective of the research was focused on the students within the UPV’s campus. During the 2018–2019 school year, there were around 25,000 students on the campus. For the survey, a questionnaire (

Figure A1 in

Appendix A) was defined by the students and a sample of 240 students took the survey. The standard error was estimated to be of 7% with a confidence interval of 95%. The students were selected through a pseudo-random sample, with a strategy of performing the survey at different times and locations in order to engage students from each of the different faculties and departments of the university. The use of this kind of samples is recommended when there is no access to databases, and it is very common in developing studies [

73]. The survey was composed of 42 questions designed to collect information about participants’ knowledge of the market and their habits regarding sustainable food consumption.

Afterwards, a qualitative study was carried out seeking to understand in detail the perceptions around the AM. A total of 15 semi-structured interviews were applied, directed to AM farmers, consumers (students and university workers), and UPV managers or administrators. Five focus groups were conducted with UPV students, as well as five participant observations during the days that the AM was operating. As time was limited, the techniques used were selected and explained by the professors of the subject.

With all this information, students categorized and analyzed the information together in the classroom through analytical coding of the data in order to establish the subject areas and to examine and to interpret relevant analytical aspects. Additionally, they produced several policy briefs for the AM. A policy brief presents a concise summary of information that can help readers understand, and likely make decisions about, government policies. Policy briefs may give objective summaries of relevant research, suggest possible policy options, or go even further and argue for particular courses of action [

74].

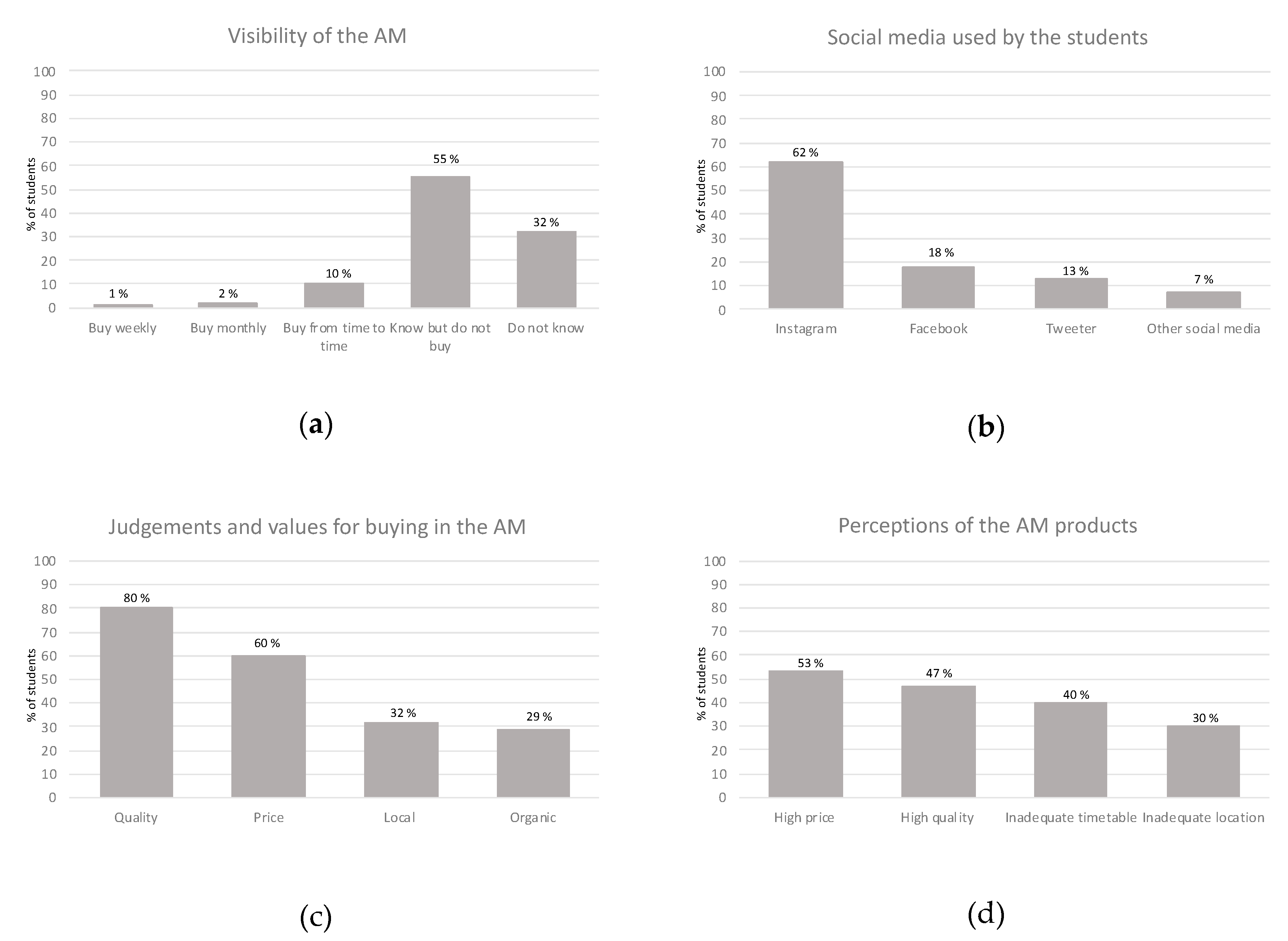

The results from the quantitative and qualitative analysis are summarized in

Figure 3 and

Table 2, respectively. The main results show that among the students 32% had never heard about the AM. Furthermore, only 10% had made purchases at the AM at least once, and only 1% of the students made purchases weekly at the AM. The results concerning the degree of students’ awareness of the AM were discussed in depth with the AM farmers in an evaluation session, and they realized that this was a very important issue for their strategy and success. Their opinion was that it was a key element for their subsequent actions in the future.

Additionally, the communication strategy was also investigated. The results showed that 81% of the students who knew of the existence of the AM did so because they passed by the location of the AM, but they did not receive any publicity via social media channels. Students highlighted (

Figure 3b) that the most common platform for informing and interacting was Instagram (62%), followed by Facebook (18%) and Twitter (13%), and finally other social media (7%). They also recommended some ideas for the AM to succeed, such as more visibility, home delivery, a more flexible timetable, and more affordable products.

Regarding the reasons and values for purchasing (or not) at the AM, more than 50% of participants noted that the prices of the AM products were more expensive than conventional products sold in supermarkets or small grocery stores. However, 40% of participants who have made purchases at least once in the AM argued that other values, such as the products being organic or local, were more important than the higher price point. Moreover, another interesting insight was that most of the participants confused concepts such as organic and agroecology, which suggests a lack of information in this issue among the students. Finally, the analysis confirmed that 80% of the participants considered the quality of products as very important when grocery shopping. With all this information and the discussion with the AM farmers, the students of the Research Methodologies course of the Master’s degree in International Cooperation at the UPV produced five policy briefs which were sent to the AM farmers.

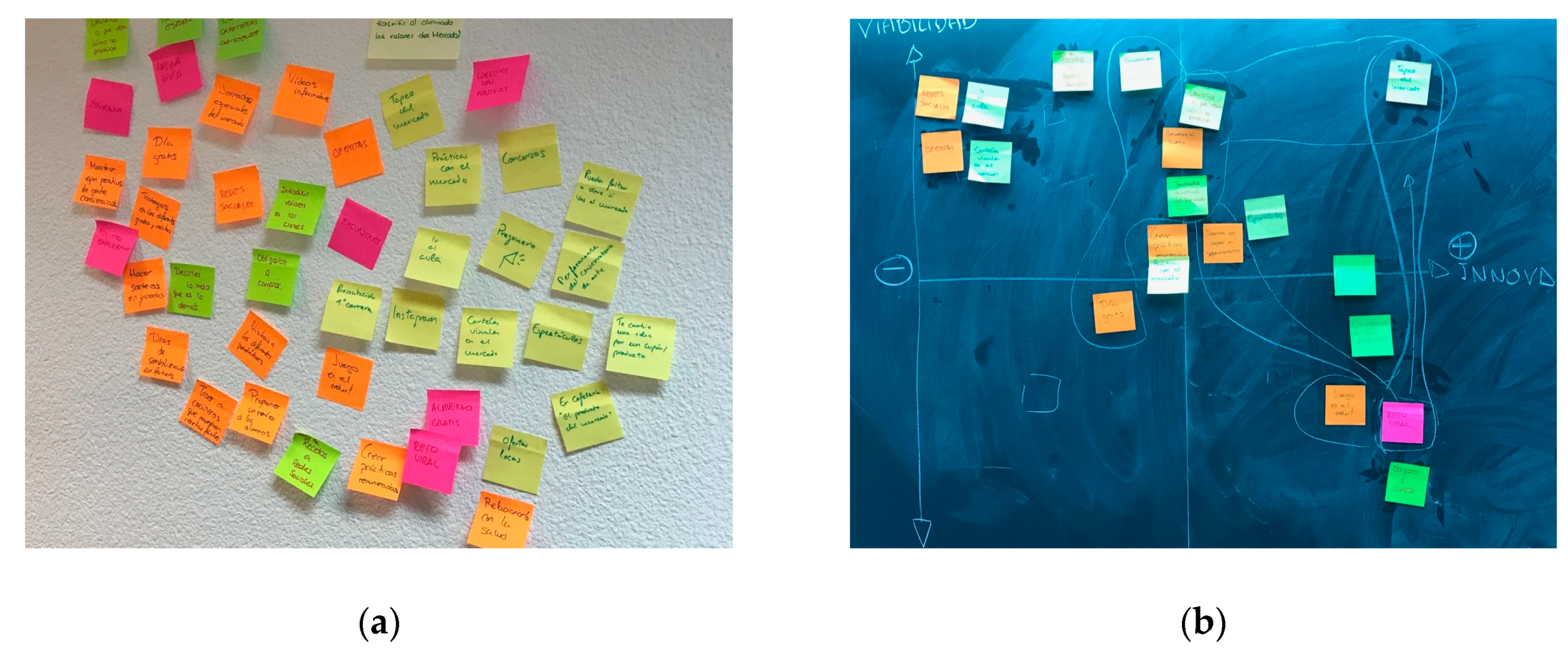

Finally, students participated in an ideation session, using Advance Creative Problem Solving (ACPS) methodology, which helped to propose creative solutions. ACPS combines design thinking and brainstorming activities to create numerous ideas, which afterwards are classified, improved, and converted into solutions [

75].

The students were divided into four groups of 5–6 people. First, a brainstorming activity was facilitated based on the principles defined by Alex Osborn [

76]. The ideation followed the process of teamstorming [

77] which is designed to create many ideas in a short period of time. The process combines the generation of new ideas and the improvement of existing ideas by exaggeration, combination, or reversal. The process encourages the participation of all students because they have to write down their ideas without judgements in all the steps. Moreover, the process is designed to fuse all the ideas in the process, supporting a combination of individual and collective creativity. More than 400 ideas were generated and then organized using a two-dimensional matrix, evaluating their viability and innovation, as shown in

Figure 4. Four solutions were chosen from among the many. The selected ones were related to strategies for engaging students with the AM, from awareness actions to social media strategies. Finally, the students combined the four solutions into the more solid proposal of creating an Instagram account for the UPV’s Agroecological Market, with awareness campaigns, presentation of farmers’ information, or contests for customers.

Moreover, the students delivered to the farmers not only the Instagram account proposal, but all the policy briefs and the data collected in the questionnaires and interviews. This final step is connected to the action part of the research process.

3.3.3. Collective Evaluation of the Experience

We understand collective evaluation as a very important step in the AR process. It is a matter of summoning and involving as many forces and actors as possible so that we can validate our results and proposals and discuss future applications of findings. This can include several meetings or just one, depending on the size and characteristics of the project’s context and the sectors involved [

78].

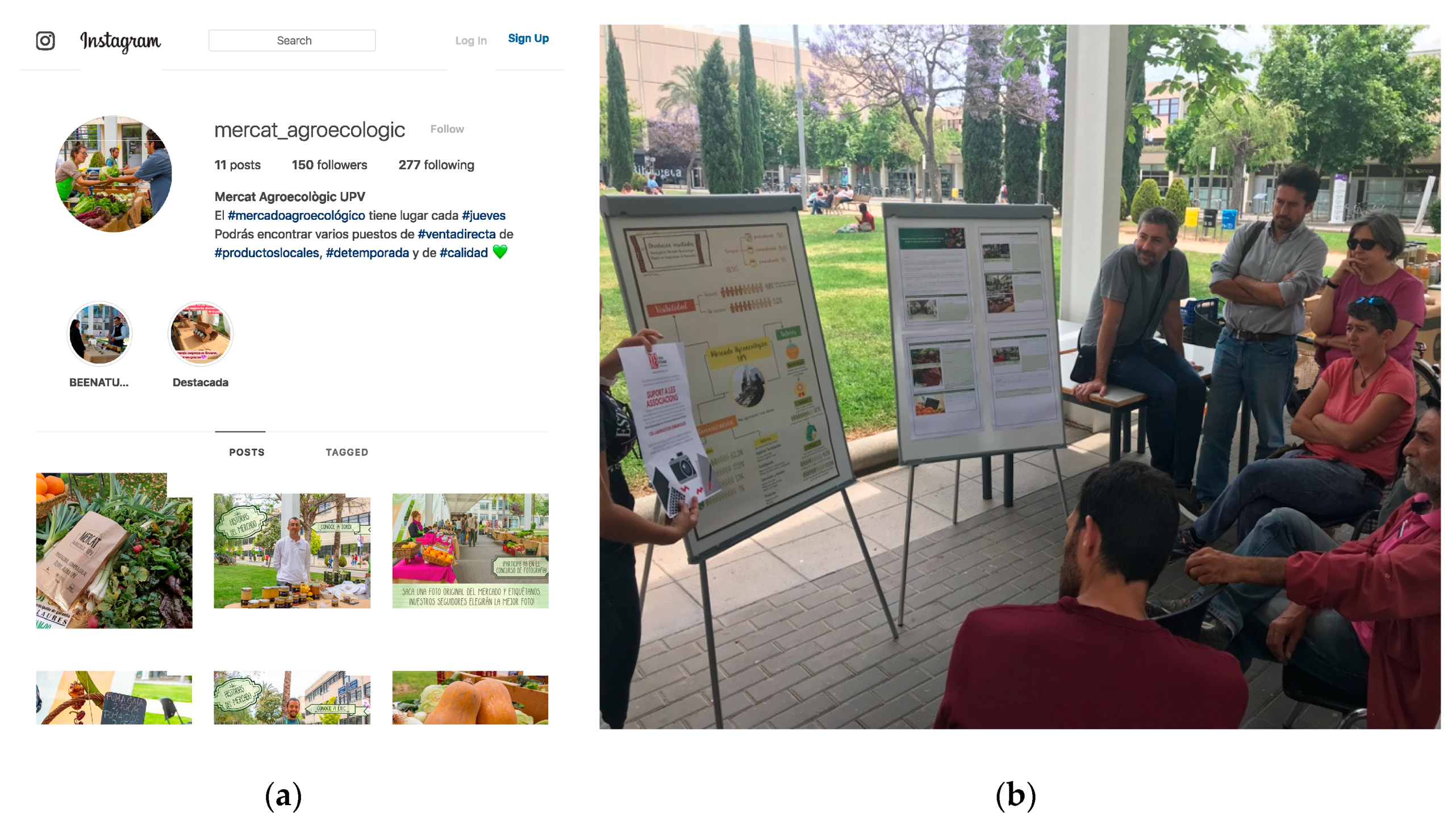

In the case of the investigation of the UPV’s Agroecological Market, the process ended with a presentation by the students to the AM members, including proposals for how to reach the objectives of the AM as defined by AM members and based in the results obtained through the AR carried out by students during the Research Methodologies course.

Figure 5 shows the evaluation with the farmers where the results of the research were presented and discussed with them for more than an hour. As part of the presentation, the students proposed the creation of an Instagram account to connect with students. Through this Instagram account, the AM can present farmers’ biographies and offer contests and challenges, as well as offer insights about agroecology to students and visitors on campus. This particular recommendation shows that this AR methodology has resulted in students going beyond initial knowledge generation; they have moved past reflection to support the design and implementation of real solutions for the AM, as is also observed in Saiz and Fernández [

36].

3.4. Critical Thinking in a Project-Based Learning Experience

Critical thinking is an inherent part of an AR project. In our project, critical self-reflection and attitudes towards reality were faced in all the research stages due to the interaction between AM farmers and students and among the students themselves. Furthermore, we introduced several activities in the design of the PBL to highlight the importance of CT and to enrich reflection during the process.

First, the PBL began and finished with two collective reflection sessions with the students from the Master’s program. The first session was used to reflect collectively about CT and how the students understood the three dimensions presented: a critical attitude towards reality, critical self-reflection, and critical action. Each student gave their own understanding of CT and then, with the assistance of the teaching staff, these definitions were collectively organized in the three previous dimensions. The second session was conducted at the end of the semester. A day of collective self-evaluation around the notions and categories of critical thinking defined at the beginning of the course was carried out. The aim of the activity was to identify through a collective reflection exercise how the pre-defined CT categories had or had not contributed to the development of the course from the students’ own perspectives and opinions. For this purpose, students analyzed, through the predefined CT categories, the methodology, contents, and activities carried out during the course. These activities were recorded by means of audio and video.

Additionally, assemblies were carried out at the end of each lecture throughout the semester. The structure of the assembly was similar to the ones proposed by many pedagogical theories, such as positive discipline [

79]. First, each participant had the opportunity to thank anyone or anything. Second, the group discussed a previously selected topic. Finally, the assembly ends with playing a teambuilding activity. This process was used for thinking and discussing the process, and to create a team strategy and culture.

An individual research dossier was planned to register their self-reflection during the course, in which both the activities carried out and the results obtained were described. These dossiers, as they represent the reflection of the learning obtained by the students during the process, were later used as evidence for the evaluation of the students’ CT development in the course.

This methodology was used in order to give space and time to the students to reflect and consider all the implications of an AR and a PBL approach. As one participant stated:

“Critical pedagogy says that education cannot be understood without being in contact with social movements. And what I understand is that they told us: "you are going to work with the market", they are telling us. "Go to reality." A reality that involves people, behind these people are farmers, and also students. What you are telling us: “you, researchers, go and connect, and go and work with these people, who have problems, challenges”. And I understand that there is a bet here. I see a way to educate that contrasts with other ways of educating, with other older ways, that could have filled us eight hours of Power Point”.

5. Results and Discussion: Critical Thinking Analysis

5.1. Critical Self-Reflection. Learning to Construct and Deconstruct Our Own Experiences and Meanings

This category of CT includes an analysis of the review of the students’ mental structures through the reflective exercises. This reflection, therefore, allowed the repositioning of the students around the research and learning process, leading them to question their role as students, the power relations between professors and themselves, and finally the notion of learning. As one student noted:

“Then, questioning our own ways of consuming. In the end, that it is a bit related to the researched-researcher relationship, that we often made statements about why people did not buy in the Agroecological Market with a little moral superiority and then you think: “But I have never bought in the Agroecological Market”, and I am in the same condition as them, right? Why am I judging them, and I am not judging myself, or why I am not rethinking, right? And it makes you also to see yourself introspectively”

Another key element analyzed during the evaluation session was that the pedagogy must be centered in human values. This was achieved by using Lego® Serious Play®, where all the views were taken into account, and by applying PBL with a very practical approach. The students observed the importance of this human values approach to logics, practices, and discourses during the semester and they valued the importance of education to enhance their abilities to see beyond the obvious reality, as explained by one of the participants:

“Then in Lego® Serious Play®, we all agree that it helped us a lot to see the different internal dynamics. When you are working with figures, and you return to the form of a plenary assembly, how the relationships and different personalities, egos.. come to light and it is much easier to fall into conflict and active listening disappears, or it doesn’t disappear, but it is much harder to maintain.”

The methodologies used in the AR project also had repercussions for other aspects related to critical self-reflection where the importance of the pedagogical process stands out as a form of expression and construction of narratives in a horizontal way, encouraging creativity through play, as well as revealing the importance of emotions. This aspect of the applied methodologies also allowed for the creation of spaces of containment, care, affection, and security, particularly from a gender perspective, as one female student stated: “This process generated a space where we could feel safe”. This atmosphere was created by proposing an assembly in each session where the students had the opportunity to thank and express their feelings and also discuss different topics related to the lecture’s environment. The results show that the students valued positively these moments during each session and they felt that it was useful for reducing the tensions in the classroom although they would have liked to use it a bit further asking for forgiveness, as was expressed by one of the participants:

“I would like to add, for example, that we finished the assembly and said what we thought about the class, and we thanked other people, but I think that from a critical thinking point of view, I would, at least, add the possibility to apologize because I think that during all the practices there are always conflicts, then, I think it is also important to ask for forgiveness.”

Finally, another aspect also highlighted in this category of analysis was the use of collective reflection, as it allowed students to look at themselves and review themselves through the eyes of the other by valuing what they learned from others and articulating how this learning was useful for questioning themselves. Aspects related to identity such as place of origin, family, childhood, and friends were continually challenged and reviewed. The fact of facing problems and real situations revealed the importance of interpersonal relationships based on seeing through the eyes of the other as we become aware of our own situations of privileges and opportunities in life. The fact that the AM is part of the daily life of students, as part of the usual landscape of the university, was resituated through a critical look at the importance and role of identity, in the sense of “what it is proper” or “who we are”. The latter highlights the importance and value of learning from “the local” in order to understand global processes. These changes involving new approaches, definitions, and practices will help us, as a community, to relate with our immediate environment.

5.2. Critical Action. We Ask Ourselves Why Things Happen

With a focus mostly on the external (social emancipation), critical action can be understood as the questioning of the set of hegemonic values, ideas, and practices for a social transformation. One aspect that emerges in this category, identified mainly in the students’ dossiers from PBL, is the importance of defending and prioritizing ethical values associated with sustainability which can be translated into logics, practices, and discourses to create the tensions that are necessary to overcome obstacles that obstruct change in our societies.

The reflection around concepts such as sustainable food or development was present from the beginning of the process when a roundtable with AM members was conducted. The participants increased their awareness of food systems and of farmers’ perspectives, and they realized the importance of individual actions to achieve real social changes, as explained by one of the students during the final evaluation of the process:

“So, the Agroecological Market has its own problems, right? And its relationship with the university, there is a tension. We are part of that, we also live our tensions, but that tension will generate changes when emerges. And the planet is suffering at the moment. So, that’s why we put the people with the producers here, but also the Master’s degree, the professors, the university and the planet, because there is a tension that is generating transformations for a change, we hope it is for the better”.

Regarding this category of CT analysis, we can say that it was facilitated in part by the nature of the course itself as well as by the use of the PBL methodology.

In this sense, the contradiction between the values of solidarity and communion that the Agroecological Market tries to transmit and the dominant values of contemporary society (such as selfishness and individualism) generates a tension that students clearly identify as a process that triggers change.

5.3. Critical Attitude Towards Reality. Reasoning and Analytical Skills to Form Rigorous Judgments

This dimension of CT emphasizes the importance of the evaluation of statements based on evidence, as one of the students stated:

“To go deeper into a subject with logic and impartiality, contrasting the information with reliable sources”.

One of the most important aspects of PBL is the ability of the participants to apply their work to a real-life scenario and the possibility of proposing creative solutions based on reliable data and facts. Moreover, another fundamental element was the combination of different research techniques. In the present project, participatory methodologies, such as Lego® Serious Play® and Advanced Creative Problem Solving, were used to define the focus, making sense of the context or searching for creative solutions to return to the AM farmers. For this reason, it can be argued that a systemic perspective was used during the process and the students were able to obtain more reliable information and propose more creative actions to promote the market among the campus community.

PBL as an inductive process that allowed the comparison of evidence was also an element evidenced during the analysis of the information. In this sense, the nature of the Research Methodology course allowed and facilitated the analysis and comparison of information generated during the same research process. The importance of “the process” was permanently highlighted by the students in relation to the usefulness for the generation of arguments. Similarly, the nature of the continuous assessment of the research process, where permanent evaluation becomes part of the learning process (particularly evident in the case of the qualitative research dossiers), allowed for the identification of how the position of the students in relation to different subjects evolved over time. The latter was reflected both in related aspects of the research process itself (e.g., selection of theoretical frameworks, sample sizes, or data collection techniques) as well as in an understanding of the complex characteristics of the agri-food system moving towards sustainability.

During the final evaluation session, a critical view of classical university learning was expressed by some of the participants regarding the classical methodologies normally used in higher education. However, the methodologies employed in the AR project, such as Lego® Serious Play®, PBL, or Advanced Creative Problem Solving, supplemented findings obtained through more traditional research processes, generating more rigorous judgements and arguments.

5.4. Contribution to Critical Thinking Development

As final remarks, the importance of the collective activities in the development of CT should be highlighted. As some of the students stated, the collective spaces where they could express freely and reflect on their theoretical approach, self-reflection, and emotions were of significant importance during the process. Techniques, such as assemblies at the end of each session, Lego® Serious Play®, and the final self-evaluation workshop, were of great importance to reflect, share, and discuss their own vision of the world and consumption behaviors. These techniques are easily adaptable to any course, age, and environment. Most of these techniques do not interfere with the main development of the theoretical contents of the subject and introduce a safe place to communicate and share emotions and concepts.

Moreover, the use of a practical case, such as the UPV’s Agroecological Market, enhances the perception of a social and real impact of the students’ results. For this reason, we state that PBL as an inductive process that allowed the comparison of evidence was also an element shown during the analysis of the information. In this sense, the nature of the Research Methodology course allowed and facilitated the analysis and comparison of information generated during the same AR process. The importance of “the process” was permanently highlighted by the students in relation to the usefulness for the generation of arguments and the development of students’ critical thinking.

Finally, as reflected by several participants, this process and all the techniques used in the course have induced change in their points of view, with ethical implications related to their consumption habits and their relationship with farmers. Most of the students met the farmers during the PBL and expressed their gratitude and respect for their jobs and ways of life. In that sense, PBL allowed students to approach the multiple realities behind the AM farmers. Analyzing the farmers’ lifestyle allowed students to see facts through the eyes of “the other”, activating the critical thinking of students in terms of their own realities, their own privileged conditions, and the structures and external factors that determine the construction of these realities.

However, the outputs used for the evaluation of CT proved to be difficult to analyze. On the one hand, collective reflections at the beginning and the end of the course might produce a distorted image of the development of CT during the AR process, because natural leaders could conduct the meetings, imposing their own arguments and opinions. Also, the collected data might not reflect the frustration and uncertainty which an AR project can produce during the process. It is therefore advisable to complement future research with data gathering designed specifically for the capture of information related to the reflection by the students on the defined CT dimensions.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a project-based learning approach oriented to promote critical thinking in students through the study of the AM at the UPV, within a course dedicated to research methodologies and techniques related to development processes. By assuming research as a situated, unmasking, and relativizing activity, different pedagogical methodologies have been combined to encourage the critical attitude of students towards reality, not only from the perspective of the studied topic but also with a focus on self-awareness and self-reflection.

The AM, as a research topic, was selected because it is an initiative situated in the same precise context in which the students live the course of their daily lives. The objective was to face the critical challenge of contemporary societies in terms of a transition towards a healthy and sustainable agri-food system. For these two reasons, it has provided an opportunity not only to confront broader societal contradictions, but also to question those that are related to students’ own daily lives. Focusing the research on a topic of which students are also a part enabled them to examine broader societal problems while at the same time asking about their own role as citizens and individuals. This combination of pedagogical approaches on a specific research topic has provided valuable insights on how to develop critical thinking in higher education.

Firstly, the project has helped students to construct and deconstruct their own experiences and meanings. Taking into consideration their emotions and contrasting their opinions in what was qualified as a “safe environment” helped students to question and challenge their own beliefs and identities. The specific pedagogical processes developed in the course enabled new forms of expression and a horizontal construction of narratives in which awareness of emotions played a crucial role. Continuous assessment of the research process, where permanent evaluation became part of the learning process, allowed for the identification of how the position of the students in relation to different subjects evolved over time. Consequently, the pedagogical processes made it possible to question essential elements, such as their own role as students, the power relations between lecturers and themselves, and, finally, the very notion and implications of learning. Particularly, the use of collective reflection allowed students to look at themselves and review themselves through the eyes of the other.

Secondly, it is clear that the course has contributed to the development of a critical attitude towards reality by working within the real case of the AM, thereby allowing the students to be more aware of concepts related to food sovereignty or agroecology. Through the study of the Agroecological Market initiative, students have been able to confront agroecological principles and practices to the dominant unsustainable food model of the overall university. They have been able to understand their contradictions and how they are embedded in the daily life of the university community. They have also been able to understand the inherent difficulties that consolidating such an experience implies. However, by focusing on the development of real alternative solutions to a real problem, students recognize not only a change in their perceptions and actions and a greater consciousness toward the environment and sustainability, but also a greater understanding of the tensions and the need to address them in order to advance transformations.

Finally, the process also allowed students to develop the ability to reason and analyze in order to form their own rigorous judgements. The pedagogical approach facilitated the visualization of conflicts and tensions among the different critical views of the participants by enabling the emergence of different conceptions of the problem through a methodology that was oriented towards creating a collective interpretation rather than convincing others. In this sense, Lego® Serious Play® contributed to enabling a creative dialogue where different views were integrated, and different kinds of knowledge came into play. Awareness of personal feelings combined with systemic analysis contributed to identifying biases and developing a complete interpretation of the problem that contributed to the development of a more holistic approach to the problem. In that sense, the combination of scientific methodologies with creative approaches to analysis and interpretations enabled participants to collectively elaborate and contrast their judgments about the topic at hand. Particularly, the fact that participants have developed, implemented, and tested a real solution for the AM also contributed to addressing and deeply understanding one of the main gaps in the market: the disconnection with the youngest members of the campus community. This pedagogical approach, combining methodological research rigor with action-oriented solutions that are put into practice, enabled students to understand complex systems not only from a theoretical perspective, but also from the point of view of practitioners.

In conclusion, the PBL approach in this course increased awareness of the food system combined through individual and collective reflections. Students faced their own contradictions and conflicts, which contributed to deeper critical thinking during the research process. The students along with the farmers of the AM, were able to obtain useful data and also solutions that allow them to connect with new costumers. At the end of the process, both students and farmers were challenged to change their points of view and reflect on sustainable development in their own life and in the campus activities. Action research enabled the possibility to undertake experiential learning and helped the students to engage with real stakeholders in the sustainable food system.

Finally, through our experience, and in relation to the larger process of ED, project-based learning has proven to be an effective tool for sustainable education since it allows for a critical approach to the current globalization model by reaffirming the link between development, justice, and equity and by promoting a critical awareness oriented towards local and global action.