Examining Luxury Restaurant Dining Experience towards Sustainable Reputation of the Michelin Restaurant Guide

Abstract

:1. Introduction

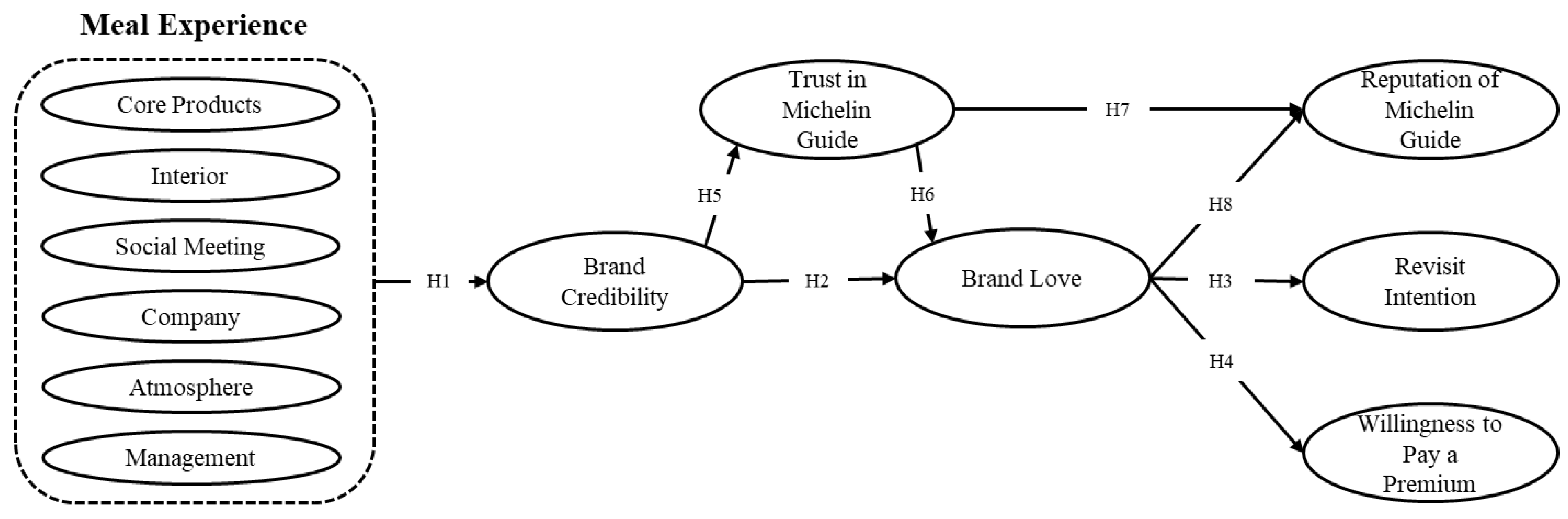

2. Literature Review

2.1. Meal Experience

2.2. Brand Credibility

2.3. Brand Love

2.4. Revisit Intention and Willingness to Pay a Premium

2.5. Trust and Reputation of Michelin Guide

3. Methods

3.1. Measurement Items

3.2. Survey Development and Data Collection

3.3. Data Screening and Analysis Techniques

3.4. Sample Profiles

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

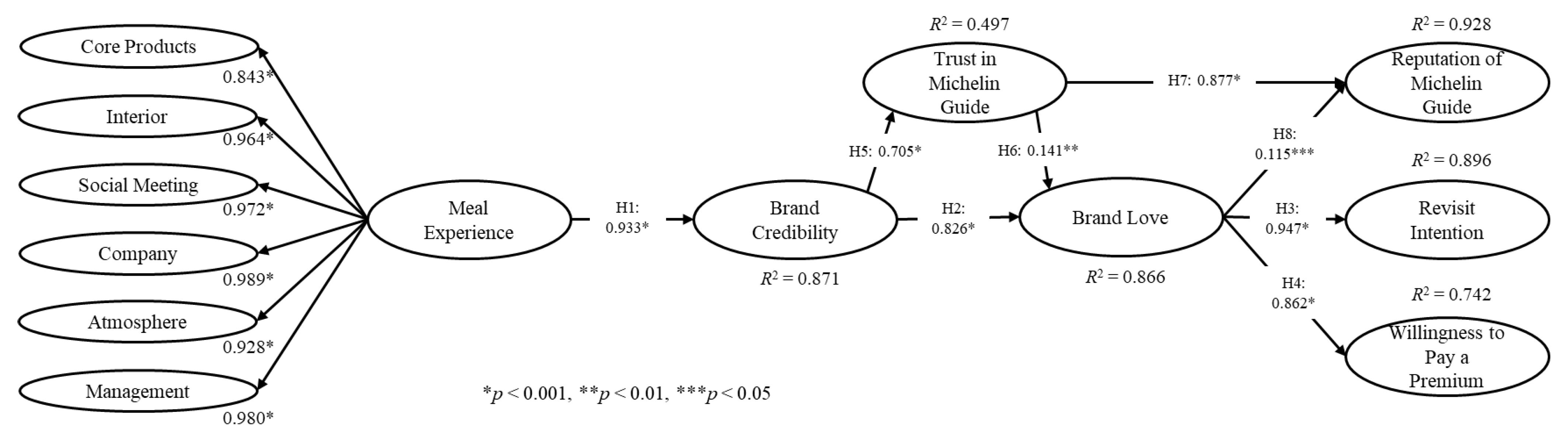

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling

4.3. Indirect Impact Assessment

5. Discussion

5.1. General Discussion

5.2. Implications

5.3. Limitations and Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Meal experience—Core product |

| This restaurant has a menu that is easily readable. (0.680) |

| This restaurant has a visually attractive menu that reflects the restaurant’s image. (0.769) |

| This restaurant has courses that give excellent taste experiences. (0.732) |

| This restaurant delivers dishes that are in accordance with the menu and description given from the staff. (0.790) |

| This restaurant has dishes that reflect the concept. (0.784) |

| Meal experience—Restaurant interior |

| This restaurant’s dining area is comfortable and easy to move around in. (0.768) |

| This restaurant’s restrooms are thoroughly clean. (0.735) |

| This restaurant uses colors, furnishing, art, and cutlery to give a complete impression. (0.741) |

| This restaurant’s physical facilities, such as buildings, signs, décor, lighting, and carpeting, are visually appealing. (0.754) |

| Meal experience—Restaurant social meeting |

| The staff at this restaurant quickly corrects anything that is wrong. (0.780) |

| The staff at this restaurant provides prompt and quick service. (0.753) |

| The staff at this restaurant makes you feel special. (0.749) |

| This restaurant has employees who are polite and show courtesy toward other staff members. (0.729) |

| This restaurant has an excellent reputation for providing its service at the time it promises to do so (e.g., drink or food is served at the time promised). (0.735) |

| This restaurant has an excellent reputation for insisting on error-free service (e.g., drinks and food are given correctly, no mistakes appear on patron’s bill). (0.744) |

| This restaurant has staff who are always willing to help patrons (e.g., willing to hang up their coats, call them a taxi, or help take photographs). (0.695) |

| This restaurant’s employees can answer your questions completely. (0.704) |

| Meal experience—Company |

| This restaurant’s employees make the entire company feel taken care of. (0.752) |

| This restaurant is aware of the occasion for the meal. (0.650) |

| This restaurant’s personal communicate with the entire company. (0.724) |

| Meal experience—Restaurant atmosphere |

| This restaurant has the ability to stimulate all senses. (0.800) |

| This restaurant atmosphere has the ability to make you feel special. (0.753) |

| Meal experience—Management control system |

| This restaurant’s personnel who well-trained, competent, and experienced. (0.721) |

| This restaurant seems to give employees support so that they can do their job well. (0.707) |

| This restaurant seems to have the customer’s best interest at heart. (0.760) |

| This restaurant has an optimal order of serving food for customers. (0.756) |

| This restaurant is dependable. (0.774) |

| Customers can trust employees at this restaurant. (0.780) |

| Brand credibility |

| This restaurant brand delivers (or would deliver) what it promises. (0.745) |

| Service claims from this restaurant brand are believable. (0.745) |

| Overtime, my experiences with this restaurant brand led me to expect it to keep its promises. (0.784) |

| This restaurant brand is committed to delivering on its claims. (0.746) |

| This restaurant brand has a name you can trust. (0.745) |

| This restaurant brand has the ability to deliver what it promises. (0.732) |

| Brand love |

| This is a wonderful restaurant brand. (0.764) |

| This restaurant brand makes me feel good. (0.741) |

| This restaurant brand is totally awesome. (0.731) |

| I have neutral feelings about this restaurant brand. (removed due to low loading, < 0.5) |

| This restaurant brand makes me very happy. (0.703) |

| I love this restaurant brand! (0.736) |

| I have no particular feelings about this restaurant brand. (removed due to low loading, < 0.5) |

| This restaurant brand is a pure delight. (0.716) |

| I am passionate about this restaurant brand. (0.728) |

| Trust in Michelin guide |

| I trust the restaurant rated by the Michelin guide. (0.828) |

| I trust the promises and assurances given by the Michelin guide. (0.821) |

| The Michelin guide gives me confidence to visit luxury restaurants. (0.809) |

| Reputation of Michelin guide |

| I believe that the Michelin guide has great recognition and prestige. (0.780) |

| I think the Michelin guide has a “good name”. (0.709) |

| I believe that the Michelin guide has a good reputation. (0.787) |

| I think the Michelin guide is one of the most important in fine dining. (0.808) |

| Revisit intention |

| I intend to visit this restaurant brand in the near future. (0.760) |

| The next time I need this kind of service, I will visit the same restaurant brand. (0.714) |

| I will continue to be loyal customer for this restaurant brand. (0.820) |

| Willingness to pay a premium |

| I am willing to pay a premium over competing services to be able to visit this restaurant brand again. (0.802) |

| I am willing to pay a lot more to dine at this restaurant brand than dining at other restaurant brands. (0.760) |

| I am willing to pay a higher price for this restaurant brand than for other restaurant brands. (0.758) |

References

- Hwang, J.; Hyun, S.S. The antecedents and consequences of brand prestige in luxury restaurants. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 17, 656–683. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, C. The Michelin-starred restaurant sector as a cultural industry. Food Cult. Soc. 2010, 13, 493–519. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Jang, Y.; Kim, Y.; Choi, H.-M.; Ham, S. Consumers’ prestige-seeking behavior in premium food markets: Application of the theory of the leisure class. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 260–269. [Google Scholar]

- Gutsatz, M.; Heine, K. Is luxury expensive? J. Brand Manag. 2018, 25, 411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, N.; Line, N.D.; Merkebu, J. Examining the impact of consumer innovativeness and innovative restaurant image in upscale restaurants. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2016, 57, 268–281. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, A.; Nayeem, T.; Murshed, F. Brand experience and consumers’ willingness-to-pay (WTP) a price premium: Mediating role of brand credibility and perceived uniqueness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 44, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- O’cass, A.; Frost, H. Status brands: Examining the effects of non-product-related brand associations on status and conspicuous consumption. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2002, 11, 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. What drives customers’ willingness to pay price premiums for luxury gastronomic experiences at Michelin-starred restaurants? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 82, 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp, J.-B.E.; Batra, R.; Alden, D.L. How perceived brand globalness creates brand value. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2003, 34, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C.; Surlemont, B.; Nicod, P.; Revaz, F. Behind the stars: A concise typology of Michelin restaurants in Europe. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2005, 46, 170–187. [Google Scholar]

- Ottenbacher, M.; Harrington, R.J. The innovation development process of Michelin-starred chefs. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 444–460. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, K.; Huiling Chen, A.; Peng, N.; Hackley, C.; Amy Tiwsakul, R.; Chou, C. Antecedents of luxury brand purchase intention. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2011, 20, 457–467. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. Antecedents and consequences of brand prestige of package tour in the senior tourism industry. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 679–695. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, C.; Zeng, Z.; Kale, S.H. The antecedents of tourists’ gaming spend: Does the brand prestige matter? Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 1086–1097. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Ham, S.; Moon, H.; Chua, B.-L.; Han, H. Experience, brand prestige, perceived value (functional, hedonic, social, and financial), and loyalty among GROCERANT customers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, T.H.; Kim, J.; Yu, J.H. The differential roles of brand credibility and brand prestige in consumer brand choice. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 662–678. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.G.; Ok, C.; Hyun, S.S. Evaluating relationships among brand experience, brand personality, brand prestige, brand relationship quality, and brand loyalty: An empirical study of coffeehouse brands. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 29, 1185–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Han, H. Examining strategies for maximizing and utilizing brand prestige in the luxury cruise industry. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 244–259. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, K.V. Development of SERVQUAL and DINESERV for measuring meal experiences in eating establishments. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2014, 14, 116–134. [Google Scholar]

- Erdem, T.; Swait, J. Brand credibility, brand consideration, and choice. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- Erdem, T.; Swait, J.; Louviere, J. The impact of brand credibility on consumer price sensitivity. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2002, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ok, C.; Choi, Y.G.; Hyun, S.S. Roles of brand value perception in the development of brand credibility and brand prestige. In Proceedings of the International ICHRIE Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 27–30 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, J.; Swait, J. The effects of brand credibility on customer loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2008, 15, 179–193. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, N.; Merunka, D. The role of brand love in consumer-brand relationships. J. Consum. Mark. 2013, 30, 258–266. [Google Scholar]

- Batra, R.; Ahuvia, A.; Bagozzi, R.P. Brand love. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, B.A.; Ahuvia, A.C. Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Mark. Lett. 2006, 17, 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.H.; Kang, S.K.; Lam, T. Reference group influences among Chinese travelers. J. Travel Res. 2006, 44, 474–484. [Google Scholar]

- Kiel, G.C.; Layton, R.A. Dimensions of consumer information seeking behavior. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 233–239. [Google Scholar]

- Mourali, M.; Laroche, M.; Pons, F. Antecedents of consumer relative preference for interpersonal information sources in pre-purchase search. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2005, 4, 307–318. [Google Scholar]

- Mourali, M.; Laroche, M.; Pons, F. Individualistic orientation and consumer susceptibility to interpersonal influence. J. Serv. Mark. 2005, 19, 164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Mattila, A.S. Why do we buy luxury experiences? Measuring value perceptions of luxury hospitality services. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1848–1867. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, K.; Lee, H.-R.; Gon Kim, W. The influence of the quality of the physical environment, food, and service on restaurant image, customer perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 200–223. [Google Scholar]

- Aseres, S.A.; Sira, R.K. An exploratory study of ecotourism services quality (ESQ) in Bale mountains National Park (BMNP), Ethiopia: Using an ECOSERV model. Ann. Leis. Res. 2019, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.L.; Hing, N. Measuring quality in restaurant operations: An application of the SERVQUAL instrument. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 1995, 14, 293–310. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson, B.J.; Stevens, P.; Patton, M. DINESERV: Measuring service quality in quick service, casual/theme, and fine dining restaurants. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 1996, 3, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, I.-B.; Öström, Å.; Johansson, J.; Mossberg, L. The five aspects meal model: A tool for developing meal services in restaurants. J. Foodserv. 2006, 17, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, K.V.; Jensen, Ø.; Gustafsson, I.-B. The meal experiences of á la carte restaurant customers. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2005, 5, 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, H.-Y.; Perks, H. Effects of consumer perceptions of brand experience on the web: Brand familiarity, satisfaction and brand trust. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2005, 4, 438–452. [Google Scholar]

- Hausman, A. A multi-method investigation of consumer motivations in impulse buying behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2000, 17, 403–426. [Google Scholar]

- Aro, K.; Suomi, K.; Saraniemi, S. Antecedents and consequences of destination brand love—A case study from Finnish Lapland. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- El-Manstrly, D. Enhancing customer loyalty: Critical switching cost factors. J. Serv. Manag. 2016, 27, 144–169. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Qu, H.; Yang, J. The formation of sub-brand love and corporate brand love in hotel brand portfolios. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 375–384. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Kiatkawsin, K.; Kim, W. Traveler loyalty and its antecedents in the hotel industry: Impact of continuance commitment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 474–495. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Thuong, P.T.M.; Kiatkawsin, K.; Ryu, H.B.; Kim, J.J.; Kim, W. Spa hotels: Factors promoting wellness travelers’ postpurchase behavior. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2019, 47, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, B.; Yu, J.; Han, H. The role of loyalty programs in boosting hotel guest loyalty: Impact of switching barriers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, 102328. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, A.; Zehir, C.; Kitapçı, H. The effects of brand experiences, trust and satisfaction on building brand loyalty; an empirical research on global brands. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 1288–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Krishnan, B.; Pullig, C.; Wang, G.; Yagci, M.; Dean, D.; Ricks, J.; Wirth, F. Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Casidy, R.; Wymer, W. A risk worth taking: Perceived risk as moderator of satisfaction, loyalty, and willingness-to-pay premium price. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 32, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Lee, K.-S.; Chua, B.-L.; Lee, S.; Kim, W. Role of airline food quality, price reasonableness, image, satisfaction, and attachment in building re-flying intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 80, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Selnes, F. An examination of the effect of product performance on brand reputation, satisfaction and loyalty. Eur. J. Mark. 1993, 27, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Wang, J.; Han, H. Effect of image, satisfaction, trust, love, and respect on loyalty formation for name-brand coffee shops. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 79, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Ballester, E.; Munuera-Aleman, J.L. Brand trust in the context of consumer loyalty. Eur. J. Mark. 2001, 35, 1238–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Chumpitaz Caceres, R.; Paparoidamis, N.G. Service quality, relationship satisfaction, trust, commitment and business-to-business loyalty. Eur. J. Mark. 2007, 41, 836–867. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Torres, J.A.; Arroyo-Cañada, F.-J. Building brand loyalty in e-commerce of fashion lingerie. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2017, 21, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Keaveney, S.M. Customer switching behavior in service industries: An exploratory study. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. Young travelers’ intention to behave pro-environmentally: Merging the value-belief-norm theory and the expectancy theory. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Forlani, F.; Pencarelli, T. Using the experiential approach in marketing and management: A systematic literature review. Mercat. Compet. 2019, 3, 17–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pencarelli, T. Marketing in an experiential perspective: Toward the “experience logic”. Mercat. Compet. 2017, 2, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Vigneron, F.; Johnson, L.W. A review and a conceptual framework of prestige-seeking consumer behavior. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 1999, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Category | Distribution | Valid Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 226 | 57.1 |

| Female | 170 | 42.9 | |

| Age | Mean | 40.09 | |

| Household income (KRW, million) | Under 24.9 | 30 | 7.6 |

| 25–39.9 | 72 | 18.2 | |

| 40–54.9 | 88 | 22.2 | |

| 55–69.9 | 78 | 19.7 | |

| 70–84.9 | 64 | 16.2 | |

| 85–99.9 | 32 | 8.1 | |

| Over 100 | 32 | 8.1 | |

| Educational Background | High school or below | 36 | 9.1 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 80 | 20.2 | |

| Master’s degree | 226 | 57.1 | |

| Doctorate | 46 | 11.6 | |

| Others | 8 | 2.0 | |

| Occupation type | Full-time employment | 278 | 70.2 |

| Full-time self-employed | 53 | 13.4 | |

| Part time employment | 12 | 3.0 | |

| Unemployed | 11 | 2.8 | |

| Student | 15 | 3.8 | |

| Retired | 4 | 1.0 | |

| Stay-at-home mother/father | 23 | 8.5 | |

| Visit companionship | Alone | 7 | 1.8 |

| Family/relatives | 171 | 43.2 | |

| Friends | 99 | 25.0 | |

| Partner | 85 | 21.5 | |

| Business Colleague(s) | 34 | 8.6 | |

| Prior visit(s) frequency to the same restaurant | First time | 111 | 28.0 |

| 2–4 time | 235 | 59.3 | |

| 5–10 times | 42 | 10.6 | |

| More than 10 times | 8 | 2.0 | |

| Frequency of visiting Michelin-starred restaurants | 1 time or less a year | 126 | 31.8 |

| 1–2 times a year | 165 | 41.7 | |

| 3–5 times a year | 84 | 21.2 | |

| 6–10 times a year | 12 | 3.0 | |

| More than 10 times a year | 9 | 2.3 |

| ME | CRE | LOVE | REV | PREM | TRUST | REPU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ME | 0.981 a | ||||||

| CRE | 0.932 b (0.869) c | 0.885 | |||||

| LOVE | 0.894 (0.799) | 0.956 (0.914) | 0.890 | ||||

| REV | 0.821 (0.674) | 0.851 (0.724) | 0.929 (0.863) | 0.809 | |||

| PREM | 0.667 (0.445) | 0.718 (0.515) | 0.883 (0.780) | 0.913 (0.834) | 0.817 | ||

| TRUST | 0.636 (0.404) | 0.691 (0.477) | 0.708 (0.501) | 0.715 (0.511) | 0.790 (0.624) | 0.860 | |

| REPU | 0.695 (0.483) | 0.754 (0.568) | 0.726 (0.527) | 0.738 (0.545) | 0.649 (0.421) | 0.957 (0.916) | 0.855 |

| AVE | 0.896 | 0.562 | 0.535 | 0.587 | 0.589 | 0.671 | 0.596 |

| Standardized Estimate | t-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meal experience | → | Core product | 0.843 * | |

| Meal experience | → | Restaurant interior | 0.964 * | |

| Meal experience | → | Personal social meeting | 0.972 * | |

| Meal experience | → | Company | 0.989 * | |

| Meal experience | → | Restaurant atmosphere | 0.928 * | |

| Meal experience | → | Management control system | 0.980 * | |

| H1: Meal experience | → | Brand credibility | 0.933 | 13.275 * |

| H2: Brand credibility | → | Brand love | 0.826 | 12.570 * |

| H3: Brand love | → | Revisit intention | 0.947 | 14.921 * |

| H4: Brand love | → | Willingness to pay a premium | 0.862 | 14.318 * |

| H5: Brand credibility | → | Trust in Michelin guide | 0.705 | 12.229 * |

| H6: Trust in Michelin guide | → | Brand love | 0.141 | 3.228 ** |

| H7: Trust in Michelin guide | → | Reputation of Michelin guide | 0.877 | 12.509 * |

| H8: Brand love | → | Reputation of Michelin guide | 0.115 | 2.164 *** |

| Goodness-of-fit statistics: χ2 = 2980.565, df = 1356, χ2/df = 2.198, RMSEA = 0.055, CFI = 0.895, IFI = 0.885, TLI = 0.889, NFI = 0.823, PGFI = 0.706 * p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.05 | Total variance explained: R2 of CRE = 0.871 R2 of LOVE = 0.866 R2 of REV = 0.896 R2 of PREM = 0.742 R2 of TRUST = 0.497 R2 of REPU = 0.928 | Total impact on REV, PREM, and REPU: TRUST = 0.134, 0.122, 0.893 LOVE = 0.947, 0.862, 0.115 CRE = 0.876, 0.797, 0.724 ME = 0.818, 0.744, 0.676 | ||

| Indirect Effect of | On | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRUST | LOVE | REV | PREM | REPU | |

| ME | 0.658 * | 0.864 * | 0.818 * | 0.744 * | 0.676 * |

| CRE | - | 0.100 | 0.876 * | 0.797 * | 0.724 * |

| TRUST | - | - | 0.134 | 0.122 | 0.016 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kiatkawsin, K.; Sutherland, I. Examining Luxury Restaurant Dining Experience towards Sustainable Reputation of the Michelin Restaurant Guide. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052134

Kiatkawsin K, Sutherland I. Examining Luxury Restaurant Dining Experience towards Sustainable Reputation of the Michelin Restaurant Guide. Sustainability. 2020; 12(5):2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052134

Chicago/Turabian StyleKiatkawsin, Kiattipoom, and Ian Sutherland. 2020. "Examining Luxury Restaurant Dining Experience towards Sustainable Reputation of the Michelin Restaurant Guide" Sustainability 12, no. 5: 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052134

APA StyleKiatkawsin, K., & Sutherland, I. (2020). Examining Luxury Restaurant Dining Experience towards Sustainable Reputation of the Michelin Restaurant Guide. Sustainability, 12(5), 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052134