Abstract

Previous researchers have found that low body satisfaction may be a barrier to engaging in physical activity. Therefore, this research examines the association between self-concept, body dissatisfaction, fitness, and weight status in adolescents. The sample was formed by 303 students from primary schools, (males (n = 150) and female (n = 153)) aged 10 to 13 years (M = 11.74; SD = 0.86). Initially, participants’ BMIs, as well as waist-to-hip ratio were assessed. Later, all individuals answered a questionnaire about their perception of self-concept and body image perception. Moreover, agility run test and 6-min walking test were developed to assess children’s physical fitness. Results showed self-concept differences according to different fitness level. Moreover, some factors from self-concept emerged as relevant to explain body dissatisfaction. Finally, outcomes suggest the importance of physical fitness and the perception of competence and self-esteem in adolescent boys and girls, so these two issues might be promoted in primary school classes to improve body satisfaction.

1. Introduction

Childhood obesity has emerged as an important public health issue worldwide, which has generated consequences of physical health problems [1]. There is clear evidence that overweightness and obesity are associated with poor body satisfaction [2,3,4,5,6], which promote lower self-concept [4]. Body satisfaction it is defined as a complex and multidimensional construct of individual’s about feelings about weight and shape his body, producing a positive affect about his body image [2].

Moreover, the multifaceted nature of physical self-concept has been widely confirmed in prior studies [7,8]. In exercise psychology, the physical self-concept has been identified as a psychological component through which motor skill level in childhood reverberates into physically active and healthy lifestyles in adolescence [7] as well as higher self-esteem levels [9]. Related to the factors regarding the maintenance of physical self-concept, many studies have shown the importance of body satisfaction in order to maintain and improve physical self-concept [3,10].

A recent Irish study investigating the relationship between physical motor skills proficiency and perceived physical self-concept levels among adolescents found a significant correlation between both variables for females [11]. Physical self-concept has been shown to be related with physical motor skills (i.e., agility, movement speed…) in youth [12]. In this sense, it is important to note the inverse relationship between movement skills and weight status [13], as well as between weight status and cardiorespiratory fitness [14]. Regarding sex, some studies have not found any association between motor skill performance, physical fitness and body-mass index (BMI) in boys and girls [15].

Minor levels of self-concept are showed within students who do not engage in physical activity [16]. Research studies demonstrate that adolescents, both males and females, who participate regularly in physical activity reported a more positive physical self-concept than those who were not active [17]. The study by Padial-Ruz et al. [18] showed that self-concept was shown by individuals with higher levels of physical activity. This confirms the positive effects of physical activity at a physical and mental level and on relatedness [19], and it is more evident during the adolescent stage [20]. Other studies carried out with self-concept and physical activity, related engagement in physical activity with improved physical self-concept in a more binding way, while failing to find relationships with other dimensions of self-concept [21,22].

However, previously studies have showed a strong relationship between body satisfaction and self-concept in adolescents [3]. Body satisfaction is a key element of the self-concept configuration, especially in adolescence [22]. Older age, male gender and lower BMI were associated with better body esteem in adolescents [23]. Besides the mental health-related aspects, BD is prospectively related to unhealthy weight control behaviors, binge eating and lower levels of physical activity according to a 5-years longitudinal study [24]. On the other hand, high levels of body satisfaction can have protective effects, such as better eating habits, healthier levels of PA and a lower probability of suffering from overweight in late adolescence and early young adult ages [22,24]. According to the association between body dissatisfaction and physical activity, a worse body satisfaction has been related with lower physical activity levels [6]. The study conducted by Sánchez-Miguel et al. [25] revealed lower perceptions of the BMI in female students with lower physical activity levels. Therefore, female students who were not dissatisfied with their body, they also had lower levels of self-identity (e.g., fitness, perception of competence, strength), which can promote the decrease of physical activity levels [25]. The study conducted by Añez et al. [26] within a large sample of Spanish adolescents showed that poor body satisfaction can appear as a barrier and not a motivator to physical activity adherence in youth. Furthermore, body satisfaction can promote the progressive appearance of behaviors aimed at improving an individual’s assessment of their own physical appearance [5] and creasing the physical activity level [4,12].

Regarding to sex, some studies have found that boys scored higher in self-esteem, competence, strength, appearance and fitness than girls [27], whereas other studies revealed that girls had higher levels of appearance than boys [28]. Babic et al. [7] found that sex was a significant moderator for general physical self-concept, revealing greater values in boys than girls. In this regard, sex differences can be explained either by biological causes or by sex role stereotyped lines: boys usually reach higher achievement in most physical domains as they often show greater muscular density than girls [7].

Previously, Ozmen et al. [8] conducted a cross-sectional survey on 2101 Turkish adolescents and found that body dissatisfaction was related to low self-esteem, and perceived overweightness was also associated with low self-esteem [29]. Furthermore, there are studies that have demonstrated the negative relationship between overweightness and obesity and psychological consequences such as self-concept [4]. Levels of self-concept represent protective factors against the development of maladaptive behaviors in scholars [30]. Research studies demonstrate that adolescents, both males and females, who participate regularly in PA report a more positive physical self-concept than those who are not as active [17,18,20,21].

Taking into account previous research and according to the relationship between body satisfaction and physical activity, the authors have found negative associations between body satisfaction and physical activity in both sex, emphasizing that low body satisfaction may be a barrier to engaging in physical activity [4,12,26,31]. Thus, the aims of the study were to know the differences between anthropometric variables and fitness in function of the perceived self-concept levels, as well as test the differences between anthropometric variables and fitness regarding body dissatisfaction level in boys and girls. We hypothesized that boys and girls with higher self-concept perceived will have lower weight, BMI, waist, hip, and better fitness variables in comparison with boys and girls with lower self-concept. As a second hypothesis, it was suggested that boys with better self-concept will present higher levels of fitness, anthropometric variables, and body satisfaction.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

A total of 303 students from 8 different Primary Schools in Extremadura, Spain, volunteered to participate, (males n = 150) and females n = 153), ranging in age from 10 to 13 years old (M = 11.74; SD = 0.86). Data were collected from February to June 2018. With the aim to conduct data analysis with all variables included in the study, only students completing all the required assessments were included in the final data set. Students that were missing demographic information, physical fitness or self-concept results, and those that had physician-directed physical education (PE) waivers were excluded from the study (there were 12 missing data due to the missing information). All data were collected during normal school hours. The sample was selected according to the research convenience, respecting accessibility and involvement of the schools.

2.2. Measures

Age, sex, and level of education we assessed using self-report. Individuals’ height and weight were measured wearing light clothing and without shoes. BMI was calculated as the weight (kg)/standing height (m)2 ratio. Height was measured with a Harpender anthropometer and recorded to the nearest mm. Weight was assessed to the nearest 0.01 kg with a SECA 884 electronic balance. Adolescents’ weight status was categorized based on Cole, Bellizi, Flegal & Dietz [32] recommendations. Waist and hip assessments were taken under clothes, to the nearest 0.1 cm at the midpoint between the lowest rib and iliac crest, and at the level of widest circumference over the greater trochanters, respectively, using a Lufkin tape. The waist-to-hip ratio was calculated as waist girth divided by the hip girth.

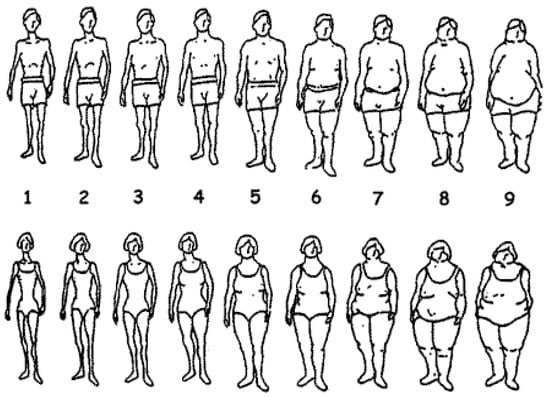

To assess self and ideal body sizes, the Stunkard Figure Rating Scale (Figure 1) was used. The Stunkard Scale consists of nine silhouette figures that increase in size from very thin (a value of 1) to very obese (a value of 9) [33]. Self-body size is the number of the figure selected by subjects in response to the prompt “Choose the figure that reflects how you think you look”. Ideal body size is the number of the figure chosen in response to the prompt “Choose your ideal figure”. For self-body size and ideal body size, dummy variables were created for the underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese body size categories. This scale has shown good validity and reliability [34]. Later, body size satisfaction was calculated. This value is defined as the difference between one’s perceived self-body size and perceived ideal body size.

Figure 1.

Stunkard Figure Rating Scale (Stunkard, Sorensen & Schulsinger, 1983).

To examine adolescents’ self-concept, a Spanish version [35] of the Physical Self-Perception Profile [36] was used. This instrument is formed of 28 items that test five factors: fitness (six items, such as “I feel very confident to continually exercise and keep my fitness”), appearance (six items, such as “I am very satisfied with how I am physically”), perceived competence (five items, such as “I am very good at almost every sport”), physical strength (five items, such as “I think that I am not as good as many others when I deal with situations in which strength is required”) and self-esteem (six items, such as “I feel a little uncomfortable in places where physical exercise and sports are practiced”). The instrument showed acceptable internal consistency (all factors were over 0.70) [37].

Physical fitness was assessed using the 6-min walking test (6MWT). The 6MWT was performed according to the standardization proposed by the American Thoracic Society [38]. A single 6MWT was developed along a flat and straight corridor of 30 m on a hard surface. Standard verbal encouragement was used during the test. Children were instructed to stop if they felt exhausted or discomfort. At the end of testing the maximum distance walked (6MWD) was determined with the aim to assess children’s cardiorespiratory level. To establish comparisons, raw data was employed due to potential bias in deriving an equation to estimate mean peak VO2máx from mean 6 MWD in children [39].

A running and turning test (shuttle run test 4 × 10 m) at maximum speed between two parallel lines and four points (four sponges) was developed to evaluate speed of movement, agility and coordination (motor performance).

2.3. Procedure

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of the First Author in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). All subjects were treated according to the American Psychological Association [40] ethics guidelines regarding consent, confidentiality, and anonymity of responses. Informed consent was provided by teachers, fathers, or mothers, explaining all the anthropometry and psychosocial variables to assess, considering that the adolescents included in the study were minors. First, subjects filled in a questionnaire, which was matched over time using a coding system to protect confidentiality. Subjects completed the questionnaire in a classroom before a physical education class. Secondly, after being split into groups of 5 individuals, they went to changing rooms to be anthropometrically measured. More than one researcher (male and female) were in the room to avoid embarrassment and to achieve a comfortable atmosphere. Finally, 4 × 10 shuttle run test and the 6-min walking test were developed. All the tests were conducted under the physical education classes, teacher agreed with all them (the results were shared with him/her), and the confidentiality of the responses were assured with the aim to not inference in students´ final marks.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was employed to assess data engagement scores. According to this test and thereafter, a U-Mann Whitney Wilcoxon test were conducted to compare differences between boys and girls in all studied variables. A Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare differences between groups for each factor of physical self-concept. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 and SPSS 23.0 software.

Regarding physical self-concept component, subjects were classified into three groups (<P25, P25–P75, >P75), according to two cut-offs values corresponding to 25th and 75th percentiles. The P25 group contains those subjects with lowest scores, and P75 subjects with highest scores. These cut-offs represent a feasible measure within primary school context [41]. The use of percentiles has been established as a useful and important alternative to mean-based indicators for obtaining conclusions when working with skewed data from questionnaires [42].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Means and standard deviations are presented in Table 1. In general, subjects show similar values in boys and girls in weight status-related physical traits and in physical fitness. Regarding self-perceived body image, boys show higher levels than girls. Finally, subjects reported scores above the midpoint of the scale for every physical self-concept dimensions.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics.

With the aim to analyze the differences between groups of high, medium and low levels of each self-concept factors, in different variables (height, weight, BMI, waist diameter, hip diameter, waist-to-hip ratio, physical fitness, 6 min’s walk test, and agility run), subjects were classified into three groups, according to two cut-offs values corresponding to 25th and 75th percentiles. The P25 group contains those subjects with lowest scores, and P75 subjects with highest scores, in order to facilitate comparisons [43,44].

Regarding to boys (Table 2 and Table 3), the results showed that there were significant differences between groups of fitness with respect to weight, BMI, waist diameter, hip diameter, waist-to-hip ratio, physical fitness, and 6 min’s walk test. Specifically, P25 group showed higher values in regarding to P25–P75 and P75 groups in weight, BMI, waist diameter, hip diameter. Furthermore, P25 group showed higher values with respect to P25–P75 group in waist-to-hip ratio and lower values with respect to P75 group in 6 min’s walk test. Furthermore, there were significant differences between groups of appearance with respect to BMI (P25 group showed high values with respect to P75 group) and waist diameter (P25 group showed higher values with respect to P25–P75 group). Likewise, there were significant differences between groups of competence with respect to weight, BMI, waist diameter, hip diameter, physical fitness, and 6 min’s walk test. Specifically, P25 group showed higher values in regarding to P25–P75 and P75 groups in weight, BMI, waist diameter, and 6 min’s walk test, and lower values with respect to the P75 group in hip diameter. Finally, there were no significant differences between groups of strength and self-esteem in the variables under investigation.

Table 2.

Physical self-concept according to weight status and physical fitness in boys.

Table 3.

Physical self-concept according to weight status and physical fitness in girls.

In relation to the differences in the perception of self-concept factors in girls, the main differences were found in fitness groups. The results showed significant differences in hip diameter, 6 min’s walk test, and agility run. P25 group showed higher values compared to P75 group in hip diameter and agility run, and with P25–75 and P75 in 6 min’s walk test. Finally, there were significant differences between groups of competence and self-esteem with respect to agility run. In both cases, P25 group showed higher values than P75 group.

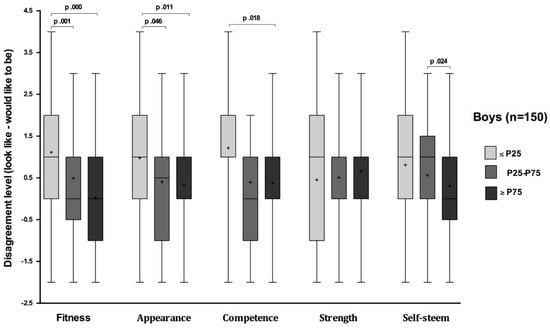

3.2. Differences in Stunkard Disagreement Level

To analyze the differences in the perception of Stunkard disagreement, subjects were classified into three groups, according to two cut-offs values corresponding to 25th and 75th percentiles. The P25 group contains those subjects with lowest scores, and P75 subjects with highest scores.

The results revealed that there were significant differences in four factors of self-concept between the three groups created in boys (Figure 1). Specifically, fitness and appearance showed significant differences in P25 regarding to P25–75 (pfitness = 0.001; pappearance = 0.046) and P75 (pfitness = <0.001; pappearance = 0.011). Furthermore, competence showed significant difference among P25 and P75 (p = 0.018) groups. The P25 group always had high levels in self-concept with respect to the other group. In contrast, self-esteem only showed significant differences between P25–75 and P75 groups (p = 0.024), with higher values in the first group. Finally, there was no difference in strength between Stunkard disagreement groups.

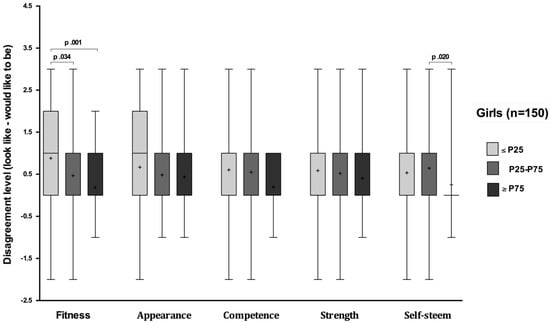

In relation to the differences in the perception of Stunkard disagreement in girls, only two factors of self-concept presented significant differences between Stunkard disagreement groups (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Fitness showed significant differences in P25 regarding to P25–75 (p = 0.034) and P75 (p < 0.001) and self-esteem between P25–75 and P75 groups (p = 0.020). In both cases, groups with less Stunkard disagreement had higher values in self-concepts factors.

Figure 2.

Stunkard disagreement level in boys.

Figure 3.

Stunkard disagreement level in girls.

4. Discussion

The main aims of the study were to know the differences between anthropometric variables and fitness regarding the perceived self-concept levels, as well as test the differences between anthropometric variables and fitness with respect to body dissatisfaction level in boys and girls. According to these aims, we hypothesized that boys and girls with better perceived self-concept will have higher values in fitness, lower anthropometrics variables, and greater body satisfaction. Moreover, it was hypothesized that boys with better self-concept will present higher levels of fitness, better anthropometric parameter, and body satisfaction.

According to the results, it is important to note the relationships found regarding fitness and BMI, waist and hip ratio, 6 min walking test, but there were not significant differences in agility regarding weight status in boys. Taking into account these results, the systematic review conducted by Babic et al. [7] examined the association between physical activity and physical self-concept in children and adolescents. The findings suggested that general physical self-concept and its sub-domains (i.e., perceived competence, perceived fitness and perceived appearance) are significantly associated with physical activity in young people. The research conducted by Padial-Ruz et al. [18] found that self-concept, in all of its dimensions, achieved a higher level among individuals who engaged in PA. This confirms the positive effects of PA at a physical and mental level, on social relations, this being even more evident during the adolescent stage [20]. Other studies carried out on self-concept relate engagement in PA with improved physical self-concept in a more binding way, while failing to find relationships with other dimensions of self-concept [21]. However, the intervention effect based on physical activity tended to diminish the gap self-concept and self-worth between groups.

On the other hand, in children, previous studies [31,45] revealed that only significant differences emerged in girls regarding the relationship between perception of fitness and agility according weight status (those girls with a better weight status showed lower scores in the agility test). Nevertheless, Utesch et al. [31] did not study the differences between boys and girls, and they revealed that higher levels of self-concept were related with greater values in physical activity. Up to our knowledge, this is an important finding with respect to other studies which did not test in depth the relationships/differences between boys and girls.

Furthermore, and according to the BMI results in girls, and as was suggested by Hardy et al. [14], there is a relationship between skill competence and being overweight, and it seems that in girls this association is emphasized. In this regard, the research developed by Jarvis et al. [15] showed that fitness and physical activity levels are more important in girls than boys. Their investigation revealed greater differences in girls compared to boys from 9 to 12 years old. In addition, the boys were had best values of physical activity levels than girls.

Our results did not find significant differences among weight and self-esteem strength in boys and girls. However, significant differences were showed between self-esteem and agility run regarding weight status in girls. Thus, it seems to reinforce the idea to have a good motor performance to improve self-esteem in girls, but it did not seem the same with boys. This finding support the idea that between boys and girls the relationship between locomotor skills and self-concept is not clear [14]. This is an important issue to investigate in further studies, since it has been demonstrated that boys spend more time playing/practicing physical activity in spare places than girls from early ages [46,47].

Moreover, an important issue to highlight is the importance of BMI and perception of appearance in boys but not in girls. This result is consistent with previous outcomes [2,3,4,25] which found lower scores in appearance in boys compared to girls, as well as a strong relationship between BMI and appearance. This might be explained through the greater participation in physical activities and sports among male sex, which exclude and/o identify those boys who do not engage in, affecting their perception of appearance [5]. This idea is supported by Prioreschi et al. [47] who revealed that boys were significantly more active than girls throughout the day, regardless of age or developmental stage, as well as it is important to note that physical activity intensity increased significantly with age (regardless of developmental stage). Therefore, the hypothesis was confirmed, although the differences found were not as expected.

Previous studies [22,48] have pointed out that differences between male and female participants were found for the different types of sports. In females, body dissatisfaction concerns were significantly lower among those who practiced non-aesthetic/non-lean and non-aesthetic/lean sports as compared to those who practiced aesthetic/lean physical activity or were inactive, in terms of the desire to lose weight and the discrepancy [22]. In males, however, only aesthetic/lean physical activity participants were more concerned about their body dissatisfaction. Apart from that, non-aesthetic/lean adolescent PA participants were the only group that showed a desire to be bigger [22]. This results could be explained by most traditional approach that is focused on the pressures that the characteristics of each type of sport put on their participants, which somehow determines their success [48].

The second hypothesis suggested that boys and girls with better self-concept will present higher levels of fitness, anthropometric variables, and body satisfaction. Considering the results, boys who are more dissatisfied with their body image, had lower appearance and fitness score, respecting those boys who are body dissatisfied. Nevertheless, it is highlighted that there were not significant differences between body dissatisfaction and strength. This issue might be explained through the suggestion that more active people were more satisfied with their body image than less active individuals [26,49]. This finding is generally in agreement with other research examining these relationships in youth populations [12,26], which found that individuals who were most satisfied with their body were those who were more active. Moreover, the differences in perception of fitness showed by those students dissatisfied with their body size compared to those satisfied, might be explained by the low levels of physical activity that those individuals who have inaccurate body size perceptions engage in [6].

As was suggested by previously studies [3,10], the psychological problem of bodily dissatisfaction is more prominent than the physiological problem of obesity. Moreover, in terms of psychological consequences, these are highlighted in boys, compared to girls, as can be seen in the self-concept results. These results are consistent with those found by Sánchez-Miguel et al. [4] who revealed more consequences in boys than girls in most of the self-concept variables regarding body dissatisfaction. Regarding boys and girls, it is important to note that those individuals who had a lower disagreement between their body real and their body ideal, showed greater scores in self-esteem, which is an important variable in predicting body dissatisfaction [9].

Regarding the effects of weight status and body dissatisfaction, [3] found that the body dissatisfaction was unrelated to self-esteem among underweight girls, whereas for all other weight status groups—average, overweight, and obese—the association was substantial. In addition, mean levels of body dissatisfaction were lower and levels of self-concept higher among underweight girls. These findings may reflect the fact that in females, underweight tends to be positively regarded in the media, by peers and even by family [50]. Hence, body dissatisfaction in underweight girls is less likely to be reinforced by individuals in their social environment, which may reduce its association with self-concept. In boys, by contrast, underweight is as likely, if not more likely, to be stigmatized as overweight [3,50], so that such a “protective effect” would not be expected. Therefore, the second hypothesis is confirmed.

In summary, this study shows the importance of self-concept and body satisfaction to promote physical activity and motor performance. Nevertheless, this last premise should be taken with caution because there are several studies showing that low body satisfaction may be a barrier to engaging in physical activity [26]. The main strength of this study is the use of psychological and physiological variables in the educational context. The limitations of the research included the research’s cross-sectional design, which precludes making casual inferences about the impact of self-concept, body dissatisfaction on fitness tests. Thus, further studies are needed to determine the mechanism responsible for the effects of physical activity and body dissatisfaction on self-concept. In this regard, interventions programs with the aim to test the influence of physical activity on body dissatisfaction are needed. As a prospective future, the authors recommend using a qualitative design that allows the collection of more information from body image, self-concept, motor performance, and physical activity.

However, two further implications for practical arose from this study. First, interventions with physical activity, focusing on promoting and developing skills in their activities, increasing students´ perception of competence, with the aim to improve self-concept and fitness should be considered. Secondly, physical activities should be focused on promoting self-esteem in boys and girls, with the purpose to not generate body dissatisfaction.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our results suggest the importance of perception of physical competence and self-esteem in adolescents´ boys and girls. These two issues should be addressed and promoting in physical education classes to improve fitness and body dissatisfaction with the adequate methodology and approach. Furthermore, this study identified the importance to improve skills (i.e., agility run) with the aim of enhancing physical appearance focused on motor control skills might be developed in physical education classes in primary school students. Moreover, in physical education classes, it is important to work on body acceptation and on the relationship between perceived real and ideal body weight. Finally, the findings of the present study highlight the relevance of developing strategies aimed at improving the perception of competence and self-esteem within physical education classes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A.S.-M., F.M.L. and D.H.-A.; methodology, P.A.S.-M., D.A.A. and M.A.T.-S.; software, P.A.S.-M. and E.D.L.C.-S.; validation, P.A.S.-M., F.M.L. and D.H.-A.; formal analysis, P.A.S.-M. and E.D.L.C.-S.; investigation, P.A.S.-M. and D.A.A.; resources, D.A.A.; data curation, D.H.-A. and E.D.L.C.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.A.S.-M.; writing—review and editing, P.A.S.-M. and M.A.T.-S.; visualization, M.A.T.-S.; supervision, E.D.L.C.-S. and M.A.T.-S.; project administration, M.A.T.-S.; funding acquisition, P.A.S.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the European Community and Ministry of Economy of Extremadura (IB16193).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Ministry of Economy and Infrastructures and European Community. The authors wish to thank the schools, children and their parents who generously volunteered to participate in the study. We also acknowledge all the staff members involved in the fieldwork for their efforts and great enthusiasm.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642. [CrossRef]

- Černelič-Bizjak, M. Changes in body image during a 6-month lifestyle behaviour intervention in a sample of overweight and obese individuals. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2019, 23, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, P.A.; Mond, J.; Eisenberg, M.; Ackard, D.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. The Link Between Body Dissatisfaction and Self-Esteem in Adolescents: Similarities Across Gender, Age, Weight Status, Race/Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 47, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; González, J.J.P.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Alonso, D.A.; Leo, F.M. The importance of body satisfaction to physical self-concept and body mass index in Spanish adolescents. Int. J. Psychol. 2018, 54, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, A.G.; Alonso, D.A.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; del Río Sánchez, C. Factors Dancers Associate with their Body Dissatisfaction. Body Image 2018, 25, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, D.T.; Wolin, K.Y.; Scharoun-Lee, M.; Ding, E.L.; Warner, E.T.; Bennett, G.G. Does perception equal reality? Weight misperception in relation to weight-related attitudes and behaviors among overweight and obese US adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babic, M.J.; Morgan, P.J.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Lonsdale, C.; White, R.L.; Lubans, D.R. Physical Activity and Physical Self-Concept in Youth: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sport. Med. 2014, 44, 1589–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozmen, D.; Ozmen, E.; Ergin, D.; Cetinkaya, A.C.; Sen, N.; Dundar, P.E.; Taskin, E.O. The association of self-esteem, depression and body satisfaction with obesity among Turkish adolescents. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, H.W.; Ellis, L.A.; Craven, R.G. How do preschool children feel about themselves? Unraveling measurement and multidimensional self-concept structure. Dev. Psychol. 2002, 38, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Sánchez, G.F.; Suárez, A.D.; Smith, L. Análisis de imagen corporal y obesidad mediante las siluetas de stunkard en niños y adolescentes españoles de 3 a 18 años. An. Psicol. 2018, 34, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, O.; Belton, S.; O’Brien, W. The Relationship between Actual Fundamental Motor Skill Proficiency, Perceived Motor Skill Confidence and Competence, and Physical Activity in 8–12-Year-Old Irish Female Youth. Sports 2017, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Bustos, J.G.; Infantes-Paniagua, Á.; Cuevas, R.; Contreras, O.R. Effect of Physical Activity on Self-Concept: Theoretical Model on the Mediation of Body Image and Physical Self-Concept in Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cliff, D.P.; Okely, A.D.; Magarey, A.M. Movement skill mastery in a clinical sample of overweight and obese children. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2011, 6, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, L.L.; Barnett, L.; Espinel, P.; Okely, A.D. Thirteen-year trends in child and adolescent fundamental movement skills: 1997–2010. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2013, 45, 1965–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, S.; Williams, M.; Rainer, P.; Jones, E.S.; Saunders, J.; Mullen, R. Interpreting measures of fundamental movement skills and their relationship with health-related physical activity and self-concept. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2018, 22, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Park, S.; Kim, S.; Koh, H. Handgrip Strength Among Korean Adolescents With Metabolic Syndrome in 2014–2015. J. Clin. Densitom. 2018, 18, 1094–6950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez Sepúlveda, U.; Gómez, B.; Matsudo, M. Actividad física, rendimiento académico y autoconcepto físico en adolescentes de Quintero. Educación Física y Ciencia 2016, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Padial-Ruz, R.; Pérez-Turpin, J.A.; Cepero-González, M.; Zurita-Ortega, F. Effects of Physical Self-Concept, Emotional Isolation, and Family Functioning on Attitudes towards Physical Education in Adolescents: Structural Equation Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, M.; Licata, M.; Kristen, S.; Thoermer, C.; Woodward, A.; Sodian, B. Social understanding and self-regulation predict pre-schoolers’ sharing with friends and disliked peers. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2015, 39, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickman, K.; Nordlund, M.; Holm, C. The relationship between physical activity and self-efficacy in children with disabilities. Sport Soc. 2018, 21, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, L.B.; Lund-Cramer, P.; Brondeel, R.; Smedegaard, S.; Holt, A.D.; Skovgaard, T. Improving children’s physical self-perception through a school-based physical activity intervention: The Move for Well-being in School study. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2018, 14, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Bustos, J.G.; Infantes-Paniagua, Á.; Gonzalez-Martí, I.; Contreras-Jordán, O.R. Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescents: Differences by Sex, BMI and Type and Organisation of Physical Activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K.-K.; Pang, J.S.; Lai, C.-M.; Ho, R.C. Body esteem in Chinese adolescents: Effect of gender, age, and weight. J. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr-Anderson, D.J.; Larson, N.I.; Nelson, M.C.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M. Does television viewing predict dietary intake five years later in high school students and young adults? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; Leo, F.M.; Amado-Alonso, D.; Pulido, J.J.; Sánchez-Oliva, D. Relationships between Physical Activity Levels, Self-Identity, Body Dissatisfaction and Motivation among Spanish High School Students. J. Hum. Kinet. 2017, 59, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Añez, E.; Fornieles-Deu, A.; Fauquet-Ars, J.; López-Guimerà, G.; Puntí-Vidal, J.; Sánchez-Carracedo, D. Body image dissatisfaction, physical activity and screen-time in Spanish adolescents. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klomsten, A.T.; Skaalvik, E.M.; Espnes, G.A. Physical Self-Concept and Sports: Do Gender Differences Still Exist? Sex Roles 2004, 50, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohbeck, A.; Tietjens, M.; Bund, A. Physical self-concept and physical activity enjoyment in elementary school children. Early Child. Dev. Care 2016, 186, 1792–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, J.; Denyer, G.; Steinbeck, K.S.; Caterson, I.D.; Hill, A.J. Obesity and Risk of Low Self-esteem: A Statewide Survey of Australian Children. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 712–718. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Sánchez, M.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; García-Marmol, E.; Chacón-Cuberos, R. Motivational Climate in Sport Is Associated with Life Stress Levels, Academic Performance and Physical Activity Engagement of Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utesch, T.; Dreiskämper, D.; Naul, R.; Geukes, K. Understanding physical (in-) activity, overweight, and obesity in childhood: Effects of congruence between physical self-concept and motor competence. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, T.J.; Bellizzi, M.C.; Flegal, K.M.; Dietz, W.H. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: International survey. BMJ 2000, 320, 1240–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stunkard, A.; Sorensen, T.; Schulsinger, F. Use of the Danish adoption register for the study of obesity and thinness. Res. Publ. Assoc. Res. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1983, 60, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Carraça, E.V.; Markland, D.; Silva, M.N.; Ryan, R.M. Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, J.A.; Cervelló, E.; Vera, J.A.; Ruíz, L.M.; Gimeno, E. Physical Self-Concept of Spanish Schoolchildren: Differences by Gender, Sport Practice and Levels of Sport Involvement. J. Educ. Hum. Dev. 2007, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, K.R. The physical self-perception profile. Manual; Northern Illinois University: DeKalb, IL, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: Hightstown, NJ, USA, 1978; p. 416. [Google Scholar]

- Crapo, R.O.; Enright, P.L.; Zeballos, R.J. Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. Pridobljeno 2002, 14, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, R.M.; Murthy, J.N.; Wollak, I.D.; Jackson, A.S. The six minute walk test accurately estimates mean peak oxygen uptake. BMC Pulm. Med. 2010, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, A.P. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vandoni, M.; Correale, L.; Valentina Puci, M.; Galvani, C.; Codella, R.; Togni, F.; La Torre, A.; Casolo, F.; Passi, A.; Orizio, C.; et al. Correction: Six minute walk distance and reference values in healthy Italian children: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 208179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsworth, G.R.; Osborne, R.H. Percentile ranks and benchmark estimates of change for the Health Education Impact Questionnaire: Normative data from an Australian sample. SAGE Open Med. 2017, 5, 205031211769571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, P.; Berry, G.; Matthews, J.N.S. Statistical methods in medical research Malden. MA Blackwell Sci. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts; Approved Standard—Third ed.; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, L.E.; Stodden, D.F.; Barnett, L.M.; Lopes, V.P.; Logan, S.W.; Rodrigues, L.P.; D’Hondt, E. Motor Competence and its Effect on Positive Developmental Trajectories of Health. Sport. Med. 2015, 45, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larouche, R.; Garriguet, D.; Tremblay, M.S. Outdoor time, physical activity and sedentary time among young children: The 2012–2013 Canadian Health Measures Survey. Can. J. Public Heal. 2016, 107, e500–e506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prioreschi, A.; Brage, S.; Hesketh, K.D.; Hnatiuk, J.; Westgate, K.; Micklesfield, L.K. Describing objectively measured physical activity levels, patterns, and correlates in a cross sectional sample of infants and toddlers from South Africa. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolak, L.; Murnen, S.K.; Ruble, A.E. Female athletes and eating problems: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2000, 27, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccagni, L.; Masotti, S.; Donati, R.; Mazzoni, G.; Gualdi-Russo, E. Body image and weight perceptions in relation to actual measurements by means of a new index and level of physical activity in Italian university students. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mond, J.M.; Hay, P.J.; Rodgers, B.; Owen, C.; Beumont, P.J.V. Assessing quality of life in eating disorder patients. Qual. Life Res. 2005, 14, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).