Changes in Physical Activity, Motor Performance, and Psychosocial Determinants of Active Behavior in Children: A Pilot School-Based Obesity Program

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Treatment Program

2.3. Measures

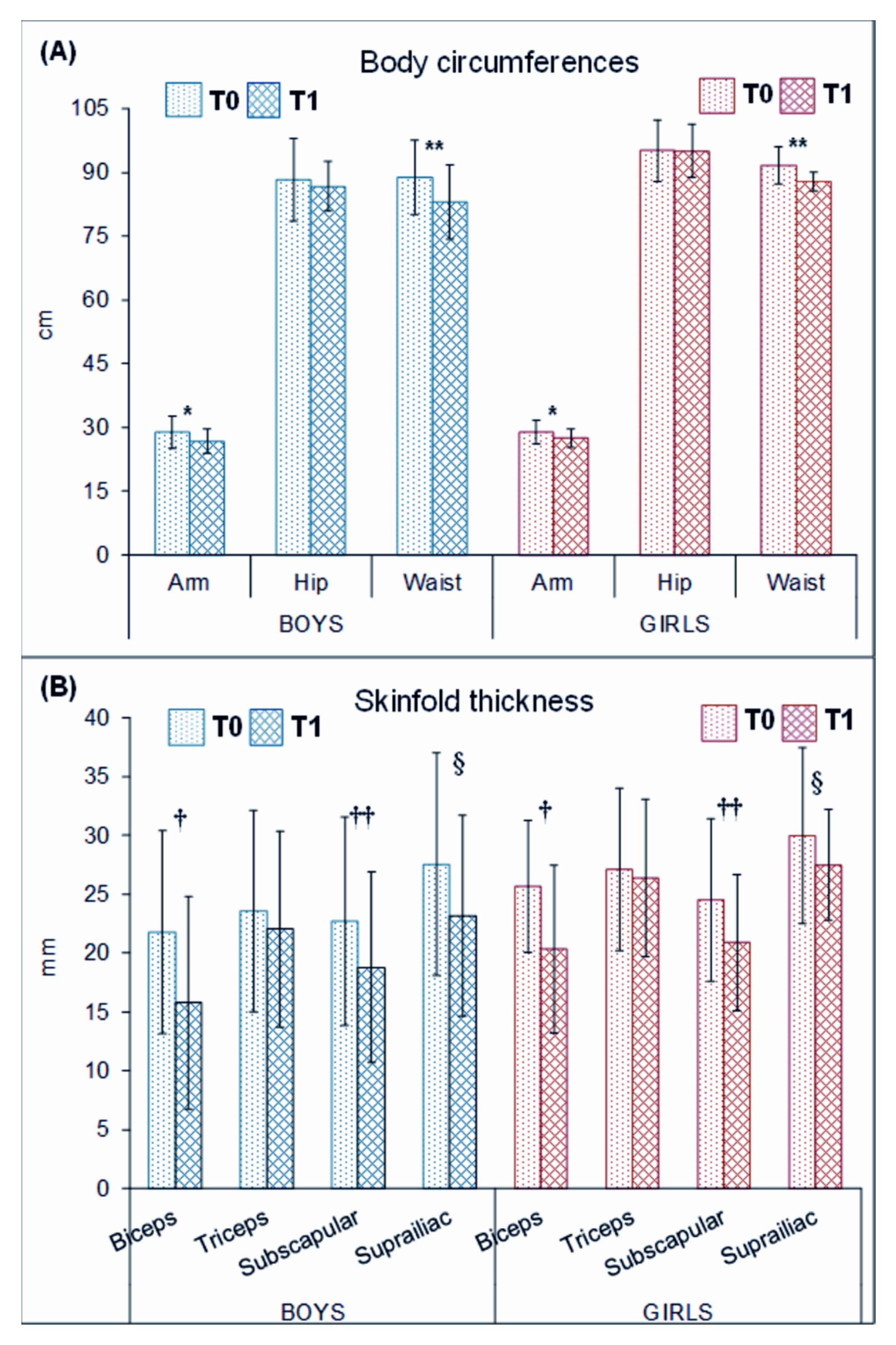

2.3.1. Body Composition

2.3.2. Physical Activity Levels

2.3.3. Physical Fitness

2.3.4. Perceived Physical Ability

2.3.5. Body Image

2.3.6. Psychobiosocial States

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsiros, M.D.; Olds, T.; Buckley, J.D.; Grimshaw, P.; Brennan, L.; Walkley, J.; Hills, A.P.; Howe, P.R.; Coates, A.M. Health-related quality of life in obese children and adolescents. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardle, J.; Cooke, L. The impact of obesity on psychological well-being. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 19, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mölbert, S.C.; Sauer, H.; Dammann, D.; Zipfel, S.; Teufel, M.; Junne, F.; Enck, P.; Giel, K.E.; Mack, I. Multimodal body representation of obese children and adolescents before and after weight-loss treatment in comparison to normal-weight children. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morano, M.; Colella, D.; Robazza, C.; Bortoli, L.; Capranica, L. Physical self-perception and motor performance in normal-weight, overweight and obese children. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2011, 21, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.J.; Fox, K.R.; Haase, A.M. Body image and physical activity among overweight and obese girls in Taiwan. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2010, 33, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finne, E.; Bucksch, J.; Lampert, T.; Kolip, P. Age, puberty, body dissatisfaction, and physical activity decline in adolescents. Results of the German health interview and examination survey (KiGGS). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, C. Body image in children and motor ability. The relationship between human figure drawings and motorability. In Body Image: New Research; Kindes, M.V., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 243–362. [Google Scholar]

- Shriver, L.H.; Harrist, A.W.; Page, M.; Hubbs-Tait, L.; Moulton, M.; Topham, G. Differences in body esteem by weight status, gender, and physical activity among young elementary school-aged children. Body Image 2013, 10, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinhas-Hamiel, O.; Singer, S.; Pilpel, N.; Fradkin, A.; Modan, D.; Reichman, B. Health related quality of life among children and adolescents: Associations with obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Hondt, E.; Deforche, B.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Lenoir, M. Relationship between motor skill and body mass index in 5-to10-year-old children. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2009, 26, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, V.P.; Stodden, D.F.; Bianchi, M.M.; Maia, J.A.; Rodrigues, L.P. Correlation between BMI and motor coordination in children. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2012, 15, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.E.; Reis, R.S.; Sallis, J.F.; Wells, J.C.; Loos, R.J.; Martin, B.W. Correlates of physical activity: Why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet 2012, 380, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortoli, L.; Bertollo, M.; Robazza, C. Dispositional goal orientations, motivational climate, and psychobiosocial states in youth sport. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2009, 47, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.R. Motivating kids in physical activity. Pres. Counc. Phys. Fit. Sports Res. Dig. 2000, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney, J.; Kwan, M.Y.; Velduizen, S.; Hay, J.; Bray, S.R.; Faught, B.E. Gender, perceived competence and the enjoyment of physical education in children: A longitudinal examination. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, C.M. Educación Emocional; Jeder: Sevilla, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Calleja, L.; García-Jiménez, E.; Rodríguez-Gómez, G. Evaluation of the design of the AEdEm Programme for Emotional Education in Secondary Education. RELIEVE 2016, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gråstén, A.; Yli-Piipari, S. The patterns of moderate to vigorous physical activity and physical education enjoyment through a 2-year school-based program. J. Sch. Health 2019, 89, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.A.; Lichtenberger, C.M. Fitness enhancement and changes in body image. In Body Image: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice; Cash, T.F., Pruzinsky, T., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 414–421. [Google Scholar]

- Kerner, C.; Haerens, L.; Kirk, D. Body dissatisfaction, perceptions of competence, and lesson content in Physical Education. J. Sch. Health 2018, 88, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deforche, B.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Tanghe, A.; Hills, A.P.; De Bode, P. Changes in physical activity and psychosocial determinants of physical activity in children and adolescents treated for obesity. Patient Educ. Couns. 2004, 55, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stodden, D.F.; Goodway, J.D.; Langendorfer, S.J.; Roberton, M.A.; Rudisill, M.E.; Garcia, C.; Garcia, L.E. A developmental perspective on the role of motor skill competence in physical activity: An emergent relationship. Quest 2008, 60, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, S. Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Children; University of Denver: Denver, CO, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, N.; Braithwaite, R.; Biddle, S.J.H. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity among adolescent girls: A Meta-analysis. Acad. Pediatr. 2015, 15, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, M.B.; Curry, W.B.; Kerner, C.; Newson, L.; Fairclough, S.J. The effectiveness of school-based physical activity interventions for adolescent girls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2017, 105, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzfischer, P.; Gruszfeld, D.; Stolarczyk, A.; Ferre, N.; Escribano, J.; Rousseaux, D.; Moretti, M.; Mariani, B.; Verduci, E.; Koletzko, B.; et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior from 6 to 11 years. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20180994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratton, G.; Fairclough, S.J.; Ridgers, N.D. Physical activity levels during the school day. In Youth Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior. Challenges and Solutions; Smith, A.L., Biddle, J.H., Eds.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2008; pp. 321–350. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, L.J.; Parsons, T.J.; Hill, A.J. Self-esteem and quality of life in obese children and adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2010, 5, 282–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morano, M.; Rutigliano, I.; Rago, A.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M.; Campanozzi, A. A multicomponent, school-initiated obesity intervention to promote healthy lifestyles in children. Nutrition 2016, 32, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bircher, J.; Kuruvilla, S. Defining health by addressing individual, social, and environmental determinants: New opportunities for health care and public health. J. Public Health Policy 2014, 35, 363–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Greenberg, D.F. Linear Panel Analysis. Models of Quantitative Change; Academic Press: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski, R.J.; Ogden, C.L.; Guo, S.S.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M.; Flegal, K.M.; Mei, Z.; Wei, R.; Curtin, L.R.; Roche, A.F.; Johnson, C.L. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: Methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002, 11, 1–190. [Google Scholar]

- Istituto Nazionale di Ricerca per gli Alimenti e la Nutrizione (INRAN). Linee Guida per una Sana Alimentazione Italiana Guidelines for Healthy Italian Food Habits. 2003. Available online: http://nut.entecra.it/648/Linee_Guida.html (accessed on 17 May 2019).

- Campanozzi, A.; Avallone, S.; Barbato, A.; Icone, R.; Russo, O.; De Filippo, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Pensabene, L.; Malamisura, B.; Cecere, G.; et al. High sodium and low potassium intake among Italian children: Relationship with age, body mass and blood pressure. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, K.; Whittingham, N.; Carter, L.; Kerr, D.; Gore, C.; Marfell-Jones, M. Measurement techniques in anthropometry. In Anthropométrica; Norton, K., Olds, T.S., Eds.; University of New South Wales: Sydney, Australia, 1996; pp. 25–75. [Google Scholar]

- Brook, C.G. Determination of body composition of children from skinfold measurements. Arch. Dis. Child. 1971, 46, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siri, W.E. Body composition from fluid spaces and density: Analysis of methods. In Techniques for Measuring Body Composition; Brozek, J., Hanschel, A., Eds.; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 1961; pp. 223–244. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker, P.R.; Bailey, D.A.; Faulkner, R.A.; Kowalski, K.C.; McGrath, R. Measuring general levels of physical activity: Preliminary evidence for the physical activity questionnaire for older children. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1997, 29, 1344–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, K.C.; Crocker, P.R.E.; Faulkner, R.A. Validation of the physical activity questionnaire for older children. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 1997, 9, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbrozzi, D.; Bortoli, L.; Bertollo, M.; Bucci, I.; Doria, C.; Robazza, C. Age-related differences in actual and perceived levels of physical activity in adolescent girls. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2012, 114, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harre, D. The Principles of Sports Training: Introduction to the Theory and Methods of Training, 2nd ed.; Sportverlag: Berlin, Germany, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Committee of Experts on Sports Research. EUROFIT: Handbook for the EUROFIT Tests of Physical Fitness, 2nd ed.; Sports Division Strasbourg, Council of Europe Publishing and Documentation Service: Strasbourg, France, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Trecroci, A.; Cavaggioni, L.; Caccia, R.; Alberti, G. Jump rope training: Balance and motor coordination in preadolescent soccer players. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2015, 14, 792–798. [Google Scholar]

- Bortoli, L.; Robazza, C. Italian version of the perceived physical ability scale. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1997, 85, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.E. Body figure perceptions and preferences among preadolescent children. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1991, 10, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoli, L.; Robazza, C. Dispositional goal orientations, motivational climate, and psychobiosocial states in physical education. In Motivation of Exercise and Physical Activity; Chiang, L.A., Ed.; Nova Science: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Bortoli, L.; Bertollo, M.; Filho, E.; di Fronso, S.; Robazza, C. Implementing the TARGET model in physical education: Effects on perceived psychobiosocial and motivational states in girls. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W. Sadly, the earth is still round (p < 0.05). J. Sport Health Sci. 2012, 1, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoli, L.; Bertollo, M.; Vitali, F.; Filho, E.; Robazza, C. The effects of motivational climate interventions on psychobiosocial states in high school physical education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2015, 86, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoli, L.; Vitali, F.; Di Battista, R.; Ruiz, M.C.; Robazza, C. Initial validation of the Psychobiosocial States in Physical Education (PBS-SPE) scale. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Battista, R.; Robazza, C.; Ruiz, M.C.; Bertollo, M.; Vitali, F.; Bortoli, L. Student intention to engage in leisure-time physical activity: The inter play of task-involving climate, competence need satisfaction and psychobiosocial states in physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 25, 761–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morano, M.; Colella, D.; Rutigliano, I.; Fiore, P.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M.; Campanozzi, A. Changes in actual and perceived physical abilities in clinically obese children: A 9-month multi-component intervention study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morano, M.; Colella, D.; Rutigliano, I.; Fiore, P.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M.; Campanozzi, A. A multi-modal training programme to improve physical activity, physical fitness and perceived physical ability in obese children. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, A.; Fu, A.; Cobley, S.; Sanders, R.H. Effectiveness of exercise intervention on improving fundamental movement skills and motor coordination in overweight/obese children and adolescents: A systematic review. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.M.; Morgan, P.J.; van Beurden, E.; Beard, J.R. Perceived sports competence mediates the relationship between childhood motor skill proficiency and adolescent physical activity and fitness: A longitudinal assessment. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berg, P.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Fat’n happy 5 years later: Is it bad for overweight girls to like their bodies? J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 41, 415–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Goeden, C.; Story, M.; Wall, M. Associations between body satisfaction and physical activity in adolescents: Implications for programs aimed at preventing abroad spectrum of weight-related disorders. Eat. Disord. 2004, 12, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Paxton, S.J.; Hannan, P.J.; Haines, J.; Story, M. Does body satisfaction matter? Five-year longitudinal associations between body satisfaction and health behaviors in adolescent females and males. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 39, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Castillo, S.; López Sánchez, G.F.; Sgroi, M.; Díaz Suárez, A. Body image and obesity by Stunkard’s silhouettes in 14- to 21-year-old Italian adolescents. J. Sport Health Res. 2019, 2, 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Gorely, T.; Nevill, M.E.; Morris, J.G.; Stensel, D.J.; Nevill, A. Effect of a school-based intervention to promote healthy lifestyles in 7–11year old children. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Boys (n = 9) | Girls (n = 9) | Analysis of Variance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Treatment M ± SD | Post-Treatment M ± SD | Pre-Treatment M ± SD | Post-Treatment M ± SD | Ftime(1,16) | p-Value | ηp2 | |

| Height (cm) | 149.10 ± 7.51 | 150.24 ± 6.64 | 151.89 ± 4.44 | 154.32 ± 4.87 | 5.16 | 0.037 | 0.24 |

| Weight (kg) | 57.27 ± 13.22 | 53.80 ± 9.70 | 61.46 ± 8.19 | 59.88 ± 7.17 | 2.11 | 0.166 | 0.12 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.58 ± 4.44 | 23.83 ± 4.09 | 26.59 ± 2.92 | 25.11 ± 2.35 | 10.28 | 0.006 | 0.39 |

| BMI percentile | 95.06 ± 3.56 | 90.71 ± 6.36 | 96.37 ± 1.94 | 94.38 ± 2.67 | 18.52 | 0.001 | 0.54 |

| BMI z-score | 1.84 ± 0.54 | 1.47 ± 0.51 | 1.87 ± 0.31 | 1.64 ± 0.30 | 16.53 | 0.001 | 0.51 |

| Body fat (%) | 37.02 ± 6.43 | 33.17 ± 7.57 | 42.89 ± 4.21 | 40.00 ± 3.88 | 19.67 | <0.001 | 0.55 |

| Physical activity levels | 1.66 ± 0.39 | 2.48 ± 0.64 | 1.84 ± 0.50 | 2.58 ± 0.79 | 38.12 | <0.001 | 0.70 |

| Physical fitness | |||||||

| Vertical jump (cm) | 19.58 ± 6.28 | 22.57 ± 8.47 | 15.78 ± 8.17 | 17.83 ± 4.39 | 5.76 | 0.029 | 0.27 |

| Medicine ball throw (m) | 4.08 ± 0.65 | 4.50 ± 0.88 | 3.53 ± 0.65 | 4.07 ± 0.67 | 36.85 | <0.001 | 0.70 |

| 10 × 5 m agility shuttle run (s) | 23.77 ± 1.76 | 22.79 ± 2.13 | 25.20 ± 1.86 | 24.27 ± 1.68 | 46.64 | <0.001 | 0.75 |

| Harre circuit test (s) | 31.55 ± 6.05 | 28.28 ± 4.48 | 34.75 ± 8.00 | 30.73 ± 5.50 | 33.76 | <0.001 | 0.68 |

| Perceived physical ability | |||||||

| Positive perceptions | 14.44 ± 2.19 | 17.89 ± 2.21 | 15.22 ± 1.72 | 19.44 ± 2.01 | 37.20 | <0.001 | 0.70 |

| Negative perceptions | 15.78 ± 2.49 | 20.89 ± 3.22 | 17.67 ± 2.06 | 23.11 ± 2.21 | 60.27 | <0.001 | 0.79 |

| Body dissatisfaction | 1.72 ± 0.62 | 0.92 ± 0.50 | 1.50 ± 0.50 | 1.17 ± 0.56 | 13.06 | 0.002 | 0.45 |

| Psychobiosocial states | |||||||

| Pleasant/functional | 2.25 ± 0.81 | 2.56 ± 0.76 | 2.73 ± 1.12 | 2.89 ± 0.53 | 0.96 | 0.342 | 0.57 |

| Unpleasant/dysfunctional | 1.08 ± 1.10 | 0.57 ± 0.43 | 0.84 ± 1.02 | 0.54 ± 0.61 | 2.78 | 0.115 | 0.15 |

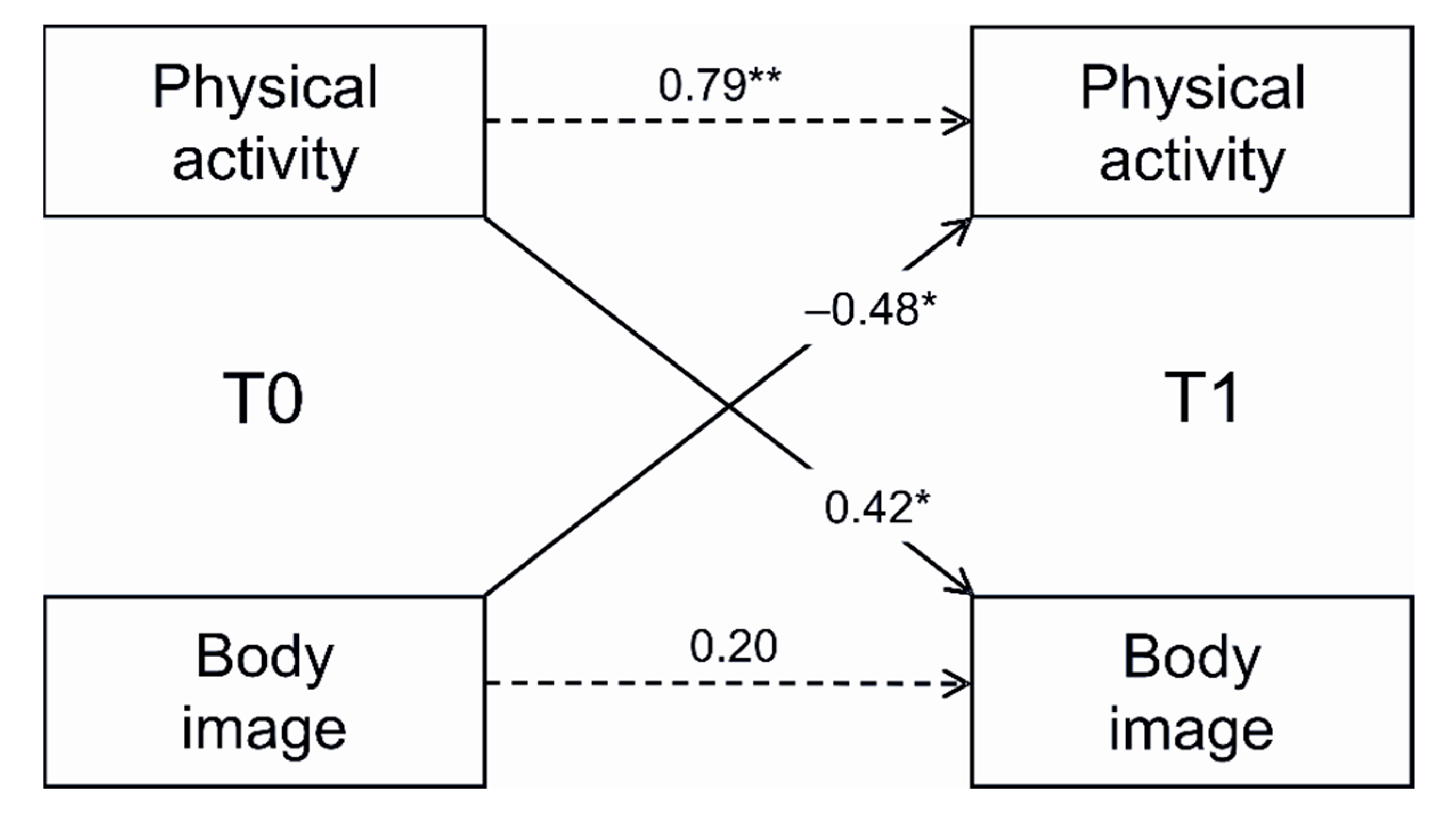

| Dependent Variables | Entered Variables | β | F | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Activity (T1) | ||||

| Step 1 | 3.85 * | 0.45 | ||

| Gender | 0.05 | |||

| Age | 0.06 | |||

| PA (T0) | 0.66 ** | |||

| Step 2 | 5.87 ** | 0.64 | ||

| Gender | 0.16 | |||

| Age | 0.12 | |||

| PA (T0) | 0.79 *** | |||

| Body image (T0) | −0.48 * | |||

| Body image (T1) | ||||

| Step 1 | 0.76 | 0.37 | ||

| Gender | −0.27 | |||

| Age | −0.15 | |||

| Body image (T0) | 0.30 | |||

| Step 2 | 1.19 | 0.52 | ||

| Gender | −0.14 | |||

| Age | −0.29 | |||

| Body image (T0) | 0.20 | |||

| PA (T0) | 0.42 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morano, M.; Robazza, C.; Rutigliano, I.; Bortoli, L.; Ruiz, M.C.; Campanozzi, A. Changes in Physical Activity, Motor Performance, and Psychosocial Determinants of Active Behavior in Children: A Pilot School-Based Obesity Program. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031128

Morano M, Robazza C, Rutigliano I, Bortoli L, Ruiz MC, Campanozzi A. Changes in Physical Activity, Motor Performance, and Psychosocial Determinants of Active Behavior in Children: A Pilot School-Based Obesity Program. Sustainability. 2020; 12(3):1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031128

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorano, Milena, Claudio Robazza, Irene Rutigliano, Laura Bortoli, Montse C. Ruiz, and Angelo Campanozzi. 2020. "Changes in Physical Activity, Motor Performance, and Psychosocial Determinants of Active Behavior in Children: A Pilot School-Based Obesity Program" Sustainability 12, no. 3: 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031128

APA StyleMorano, M., Robazza, C., Rutigliano, I., Bortoli, L., Ruiz, M. C., & Campanozzi, A. (2020). Changes in Physical Activity, Motor Performance, and Psychosocial Determinants of Active Behavior in Children: A Pilot School-Based Obesity Program. Sustainability, 12(3), 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031128