Public Agency in Changing Industrial Circular Economy Ecosystems: Roles, Modes and Structures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Different Roles and Contexts for Public Actors

2.2. The Ways of Public Involvement in Industrial CE Ecosystems

2.3. Organization and Structures of Industrial CE Ecosystems

3. Methods

3.1. Study 1: Extensive Multiple Case Study

3.2. Study 2: Focused Multiple Case Study

4. Results

4.1. Roles of Public Agency in Industrial CE Ecosystems

4.2. The Characteristics of the Relationships in Different Roles—The Two Modes

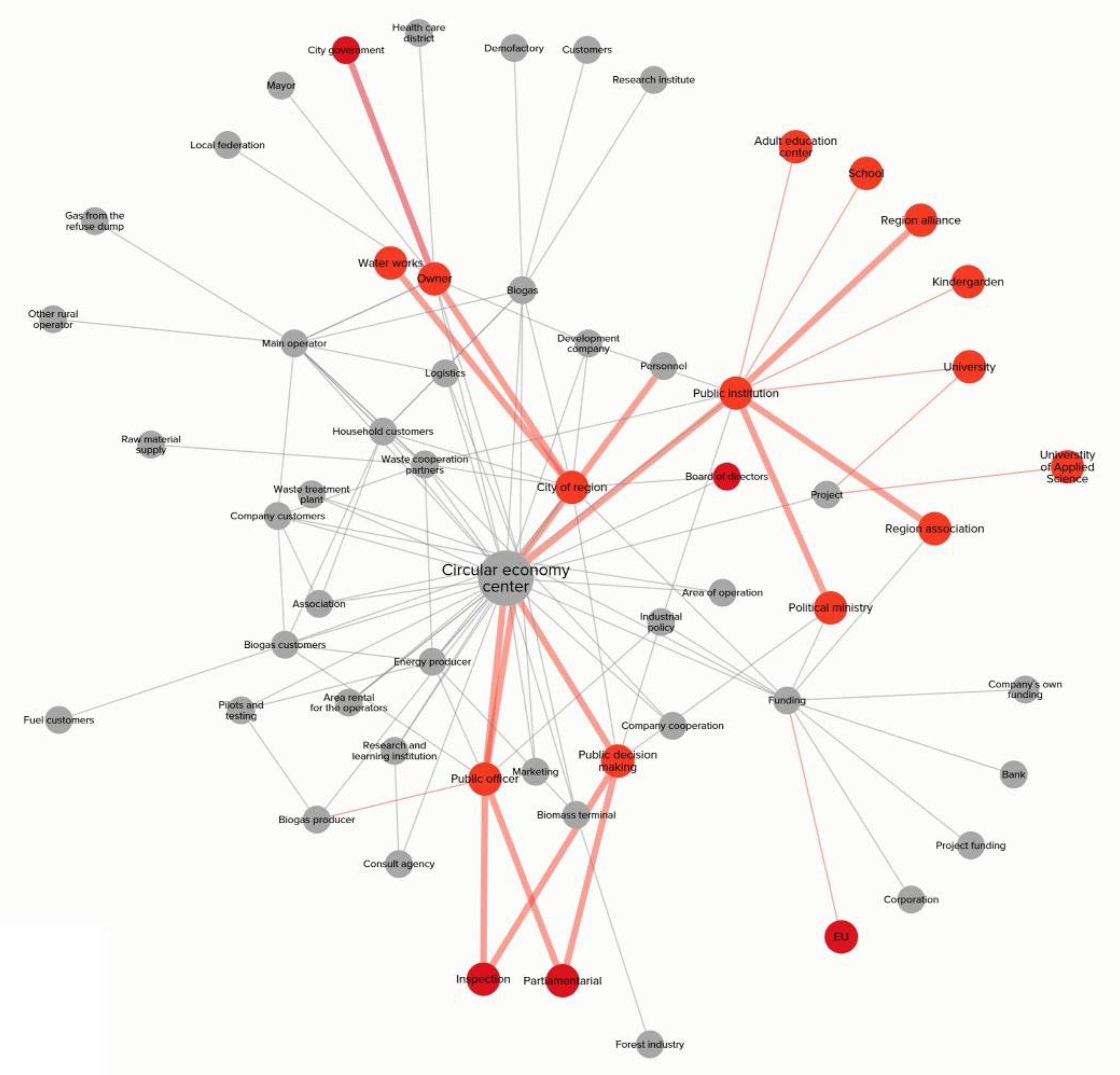

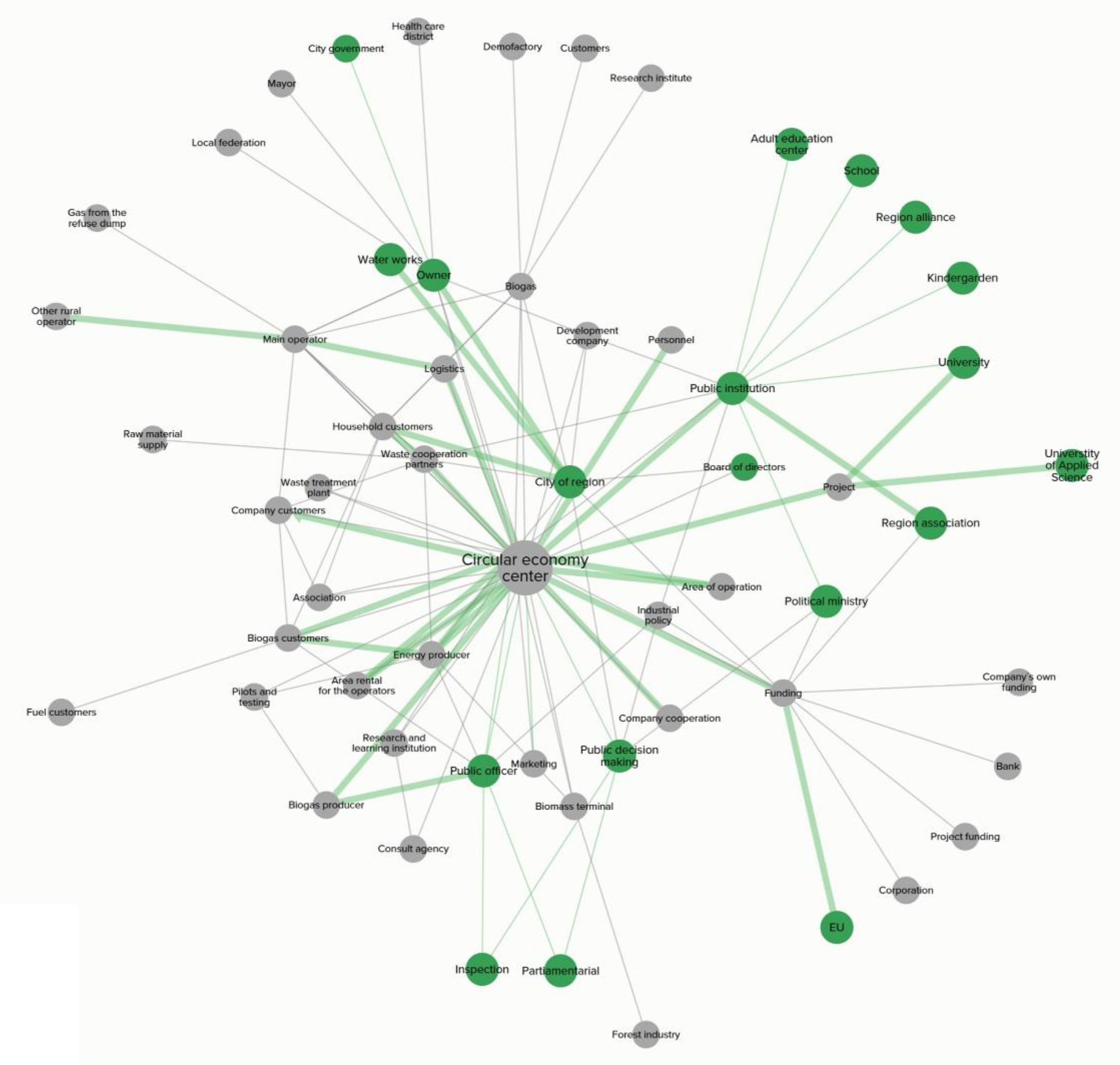

4.3. The Public Actor in Industrial CE Ecosystem Structure

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of the Key Results

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations

5.5. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bocken, N.M.; De Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; Van Der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, K.; Heikkinen, S. Sustainability Transitions at the Frontline. Lock-in and Potential for Change in the Local Planning Arena. Sustainability 2018, 10, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendeville, S.; Cherim, E.; Bocken, N. Circular cities: Mapping six cities in transition. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 26, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, J.; De Meulder, B. Interpreting circularity. Circular city representations concealing transition drivers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kębłowski, W.; Lambert, D.; Bassens, D. Circular economy and the city: An urban political economy agenda. Cult. Organ. 2020, 26, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, V.; Sahakian, M.; Van Griethuysen, P.; Vuille, F. Coming full circle: Why social and institutional dimensions matter for the circular economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J. Four ecosystem principles for an industrial ecosystem. J. Clean. Prod. 2001, 9, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruel, A.; Kronenberg, J.; Troussier, N.; Guillaume, B. Linking Industrial Ecology and Ecological Economics: A Theoretical and Empirical Foundation for the Circular Economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular Economy: The Concept and its Limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velenturf, A.P.M. Initiating resource partnerships for industrial symbiosis. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2017, 4, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulrow, J.S.; Derrible, S.; Ashton, W.S.; Chopra, S.S. Industrial Symbiosis at the Facility Scale. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, D.; Deutz, P. Reflections on implementing industrial ecology through eco-industrial park development. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1683–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarikka-Stenroos, L.; Ritala, P.; Thomas, L.D.W. Circular economy ecosystems: A typology, definitions, and implications. In Handbook of Sustainability Agency; Teerikangas, S., Onkila, T., Koistinen, K., Mäkelä, M., Eds.; Edgar Elgar: Cheltenham/Camberley, UK, 2021; pp. 15–37, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Paquin, R.L.; Howard-Grenville, J. Blind Dates and Arranged Marriages: Longitudinal Processes of Network Orchestration. Organ. Stud. 2013, 34, 1623–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchella, A.; Previtali, P. Circular business models for sustainable development: A “waste is food” restorative ecosystem. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertow, M.; Ehrenfeld, J. Organizing Self-Organizing Systems. J. Ind. Ecol. 2012, 16, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratini, C.; Georg, S.; Jørgensen, M. Exploring circular economy imaginaries in European cities: A research agenda for the governance of urban sustainability transitions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 974–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellantuono, N.; Carbonara, N.; Pontrandolfo, P. The organization of eco-industrial parks and their sustainable practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Han, F.; Cui, Z. Evolution of industrial symbiosis in an eco-industrial park in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Dijkema, G.P.J.; de Jong, M. What Makes Eco-Transformation of Industrial Parks Take Off in China? J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 19, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervero, R.; Sullivan, C. Green TODs: Marrying transit-oriented development and green urbanism. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2011, 18, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qviström, M.; Bengtsson, J. What Kind of Transit-Oriented Development? Using Planning History to Differentiate a Model for Sustainable Development. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 2516–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, B. How participatory planning processes for transit-oriented development contribute to social sustainability. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 6, 520–524. [Google Scholar]

- Ranta, V.; Aarikka-Stenroos, L.; Ritala, P.; Mäkinen, S.J. Exploring institutional drivers and barriers of the circular economy: A cross-regional comparison of China, the US, and Europe. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöggl, J.P.; Stumpf, L.; Baumgartner, R.J. The narrative of sustainability and circular economy—A longitudinal review of two decades of research. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 163, 105073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antikainen, M.; Aminoff, A.; Kettunen, O.; Sundqvist-Andberg, H.; Paloheimo, H. Circular Economy Business Model Innovation Process–Case Study. Sustain. Des. Manuf. 2017, 68, 546–555. [Google Scholar]

- Patala, S.; Hämäläinen, S.; Jalkala, A.; Pesonen, H.-L. Towards a broader perspective on the forms of eco-industrial networks. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 82, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Deutz, P.; Chen, Y. Building institutional capacity for industrial symbiosis development: A case study of an industrial symbiosis coordination network in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 1571–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herczeg, G.; Akkerman, R.; Hauschild, M.Z. Supply chain collaboration in industrial symbiosis networks. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, A.; Braccini, A.M.; Poponi, S.; Mosconi, E.M. A meta-model of interorganisational cooperation for the transition to a circular economy. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, E.A.; Evans, L.K. Industrial ecology and industrial ecosystems. J. Clean. Prod. 1995, 3, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Dijkema, G.P.J.; de Jong, M.; Shi, H. From an eco-industrial park towards an eco-city: A case study in Suzhou, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 102, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, J.A.; Tan, H. Progress toward a Circular Economy in China: The Drivers (and Inhibitors) of Eco-industrial Initiative. J. Ind. Ecol. 2011, 15, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingstrup, M.B.; Aarikka-Stenroos, L.; Adlin, N. When institutional logics meet: Alignment and misalignment in collaboration between academia and practitioners. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, X.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, Z. Institutional pressures, sustainable supply chain management, and circular economy capability: Empirical evidence from Chinese eco-industrial park firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowall, W.; Geng, Y.-J.; Huang, B.; Barteková, E.; Bleischwitz, R.; Türkeli, S.; Kemp, R.; Doménech, T. Circular Economy Policies in China and Europe. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Sarkis, J.; Wu, Z. Creating integrated business and environmental value within the context of China’s circular economy and ecological modernization. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1494–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Berkel, R.; Fujita, T.; Hashimoto, S.; Fujii, M. Quantitative Assessment of Urban and Industrial Symbiosis in Kawasaki, Japan. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morseletto, P. Targets for a circular economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Pascucci, S. Institutional incentives in circular economy transition: The case of material use in the Dutch textile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, J.L.; Paquin, R.L. Organizational Perspectives of Industrial Symbiosis: A Review and Synthesis. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Plan 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, V.; Wincent, J. Why and how to compete through sustainability: A review and outline of trends influencing firm and network-level transformation. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górecki, J.; Núñez-Cacho, P.; Corpas-Iglesias, F.A.; Molina, V. How to convince players in construction market? Strategies for effective implementation of circular economy in construction sector. Cogent Eng. 2019, 6, 1690760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Di Girasole, E.G.; Poli, G.; Regalbuto, S. Operationalizing the Circular City Model for Naples’ City-Port: A Hybrid Development Strategy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumann, F.; Tambo, T. Enterprise architecture for a facilitated transformation from a linear to a circular economy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, A.; Ashton, W.; Teixeira, C.; Lyon, E.; Pereira, J. Infrastructuring the Circular Economy. Energies 2020, 13, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, C. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner Researchers; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; de Jong, M.; Dijkema, G.P.J. Process analysis of eco-industrial park development–the case of Tianjin, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, J. On the Pragmatics of Qualitative Assessment: Designing the Process for Content Analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2006, 22, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkman, S.; Van Hezik, C. Global Assessment of Eco-Industrial Parks in Developing and Emerging Countries; The United Nations Industrial Development Organization, Vienna International Centre: Vienna, Austria, 2016; Available online: https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/2017-02/2016_Unido_Global_Assessment_of_Eco-Industrial_Parks_in_Developing_Countries-Global_RECP_programme_0.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Adams, M.; Cote, R.P.; Geng, Y.; Li, Y. Comparative study on the pathways of industrial parks towards sustainable development between China and Canada. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 128, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veleva, V.; Todorova, S.; Lowitt, P.; Angus, N.; Neely, D. Understanding and addressing business needs and sustainability challenges: Lessons from Devens eco-industrial park. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liwarska-Bizukojc, E.; Bizukojc, M.; Marcinkowski, A.; Doniec, A. The conceptual model of an eco-industrial park based upon ecological relationships. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, M. Eco-Industrial Developments in Japan; Indigo Development Working Paper #11; RPP International, Indigo Development Center: Emeryville, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Lowe, E.A.; Wei, Y.-A.; Barnes, D. Industrial Symbiosis in China: A Case Study of the Guitang Group. J. Ind. Ecol. 2007, 11, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, N.B. Industrial Symbiosis in Kalundborg, Denmark: A Quantitative Assessment of Economic and Environmental Aspects. J. Ind. Ecol. 2006, 10, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S. Industrial Symbiosis in the Kwinana Industrial Area (Western Australia). Meas. Control 2007, 40, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Feng, N. A case study of industrial symbiosis: Nanning Sugar Co., Ltd. in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2008, 52, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elabras Veiga, L.B.; Magrini, A. Eco-industrial park development in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: A tool for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xue, B.; Dong, H.; Fujita, T.; Chiu, A. Emergy-based assessment on industrial symbiosis: A case of Shenyang Economic and Technological Development Zone. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 13572–13587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J. Theory of industrial ecology: The case of the concept of diversity. Prog. Ind. Ecol. Int. J. 2005, 2, 35–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-S.; Won, J.-Y. Ulsan Eco-industrial Park: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Ind. Ecol. 2007, 11, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, A. Eco-industrial parks: The international state of art. In Eco-Industrial Parks: A Green and Place Marketing Approach; Caroli, M., Cavallo, M., Valentino, A., Eds.; Luiss University Press: Rome, Italy, 2015; pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Chinn, P.L.; Kramer, M.K. Theory and Nursing: A Systematic Approach, 5th ed.; Mosby Year Book: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ayres, L.; Knafl, K.A. Typological Analysis. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Given, L.M., Ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 901–902. [Google Scholar]

- Kluge, S. Empirically Grounded Construction of Types and Typologies in Qualitative Social Research. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2000, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnish Road Map to a Circular Economy 2016–2025. Available online: https://www.sitra.fi/en/projects/leading-the-cycle-finnish-road-map-to-a-circular-economy-2016-2025/ (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- Sitra honoured as a Leading Driver of the Circular Economy. Available online: https://www.sitra.fi/en/news/sitra-honoured-leading-driver-circular-economy-can-world-learn-finland/ (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- Kalundborg Symbiosis. Available online: http://www.symbiosis.dk/en/ (accessed on 16 February 2019).

- Geng, Y.; Xinbei, W.; Qinghua, Z.; Hengxin, Z. Regional initiatives on promoting cleaner production in China: A case of Liaoning. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1502–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leising, E.; Quist, J.; Bocken, N. Circular Economy in the building sector: Three cases and a collaboration tool. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 976–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; von Malmborg, F.; Strachan, P.A.; Ehrenfeld, J.R. Management and policy aspects of industrial ecology: An emerging research agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2004, 13, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.D.; Marsh, E.E. Content Analysis: A Flexible Methodology. Libr. Trends 2006, 55, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of the Case | Domicile | Primary Source Material |

|---|---|---|

| Burnside Industrial Park | Canada | [56] |

| Dalian Development Area (DDA) | China | [21] |

| Devens Eco-Industrial Park | USA | [57] |

| Ecopark Hartberg GmbH | Austria | [58] |

| Fujisawa Eco-industrial Park, EBARA Corporation of Japan | Japan | [59] |

| Guitang Group | China | [60] |

| Kalundborg Symbiosis | Denmark | [61] |

| Kawasaki Zero-Emission Industrial Complex | Japan | [39] |

| Kwinana Industrial Area (KIA) | Australia | [62] |

| Nanning Sugar Co., Ltd. | China | [63] |

| National Industrial Symbiosis Programme (NISP) | United Kingdom | [15] |

| Rizhao Economic and Technology Development Area (REDA) | China | [20] |

| Santa Cruz | Brazil | [64] |

| Shenyang Economic and Technological Development Zone (SETDZ) | China | [65] |

| Suzhou Industrial Park (SIP) | China (Singapore) | [33] |

| Tianjin Economic-Technological Development Area (TEDA) | China | [29] |

| Uimaharju Industrial Ecosystem | Finland | [66] |

| Ulsan Eco-industrial Park | South Korea | [67] |

| Value Park | Germany | [68] |

| Vreten Park | Sweden | [68] |

| Name of Case | Central (Public) Organization | Interviews with Key Actors | Observation, Ethnography | Secondary Source Material |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ekomo eco-industrial centre, Ämmässuo 1; Helsinki Region, Finland | Helsinki Region Environmental Services Authority HSY | 2 | Visiting the park; attending a workshop discussion; attending an online workshop (2); free-form discussion with a key actor; attending monthly meetings on project updates (ca. 20) | Annual reports; completions of the city council and other institutes; news; web pages; seminar presentation by the central organization |

| Rusko Waste Treatment Centre 2; Oulu, Finland | Kiertokaari Ltd. | 3 | Visiting the park; attending monthly meetings on project updates (ca. 20); free-form discussions with key actors; attending an online workshop | Annual reports; completions of the city council and other institutes; news; web pages; seminar presentations by the central organization (3) |

| ECO3 Kolmenkulma Eco-Industrial Park 3; Nokia, Finland | Verte Ltd. | 2 | Visiting the park; attending workshop discussion (4); free-form discussion with key actors; attending meetings of the park members and stakeholders (2) | Annual reports; completions of the city council and other institutes; news; web pages; journal article; project report; seminar presentations by the central organization (3) |

| Topinpuisto Circular Economy Hub 4; Turku, Finland | Lounais-Suomen Jätehuolto Ltd. | 3 | Attending monthly meetings on project updates (ca. 20); attending an online workshop | Annual reports; completions of the city council and other institutes; news; web pages |

| Role | Mode | |

|---|---|---|

| Facilitative | Dirigiste | |

| Operator | The operator of the park belongs to a local university. (Burnside Industrial Park, [56]) | In the park, there are different public-based departments that, e.g., assess the environmental impacts of the park attendees, determine whether an attendee or project is approved to the park or not, and monitor as well as perform environmental inspections in the park. (SIP, [33]) |

| The commission created by the state legislature guided the redevelopment of the old military base through regulatory and permit-granting actions. Alongside, a quasi-state agency manages the infrastructure, public services, and the sale and leasing of real estate within the area. (Devens Eco-Industrial Park, [57]) | In the park, there are different departments formed by the local authority. They, e.g., coordinate and manage the park, measure the pollution rates of the companies, facilitate inter-firm IS opportunities, and organize the dispersed knowledge resources in the park. (TEDA, [52]) | |

| The program, executed by 12 semi-autonomous regional offices, performed actions from promoting and building the IS network to maintaining and co-developing it. (NISP, [15]) | The main operator of the park is a local government-owned non-profit organization that provides environmental services for local companies. It is the core of the IS coordination network, as it acts as a collaboration platform between government departments and foreign organizations. (TEDA, [29]) | |

| Organizer | The state legislature created a commission to plan the reuse of the base, i.e., to generate vision and goals for the park. (Devens Eco-Industrial Park, [57]) | The park was established by the local municipality. (Ecopark Hartberg GmbH, [58]) |

| A department of the local municipality handles the secretary and visitors of the area. (Kalundborg Symbiosis, [74]) | The park was founded by the local municipality. (Vreten Park, [68]) | |

| The local municipality facilitates contacts between the park members. (Ecopark Hartberg GmbH, [58]) | The park was established when industries located in the industrial district signed a formal agreement with the government to be part of a state government initiative aiming for sustainable development. (Santa Cruz, [64]) | |

| The park is a government-to-government project between two countries. In practice, the park is located in one country, but it has been co-developed together with other countries that have special knowledge on the subject. (SIP, [33]) | ||

| The eco-transformation of the park has been government-driven and guided by national environmental policies. (TEDA, [29]) | ||

| The operator of the park is selected by companies and the local municipality government. (Ulsan Eco-industrial Park, [67]) | ||

| Financer | The local government provides financial incentives for the development of IS. (REDA, [20]) | The public actors at the municipality, province, and federal levels together cover the costs of the main operator of the park. (Burnside Industrial Park, [56]) |

| The local municipality offers the infrastructure and beneficial energy prices for the park members. (Ecopark Hartberg GmbH, [58]) | Major deal in program funding came from the government, with the aim of finding new ways to remain economically competitive under the changing and tightening regulatory environment. (NISP, [15]) | |

| The eco-transformation of the area was based on voluntary actions performed by the enterprises and financially supported by the national government. (Kawasaki Zero-Emission Industrial Complex, [39]) | ||

| The actions and services the national IS program provided were free of charge for the companies. (NISP, [15]) | ||

| Supporter | The park-located services such as shops, cafés, law offices and cinema are used by the park members and the inhabitants of the municipality. (Ecopark Hartberg GmbH, [58]) | The municipal wastewaters are treated in the park’s wastewater plant. The park also sells surplus electricity to the national grid. (Uimaharju Industrial Ecosystem, [66]) |

| There are by-product exchanges and steam and heat contracts between the park companies and the local municipality. (Kalundborg Symbiosis, [61]) | The over 1300 enterprises located in the park also include state-owned enterprises. (SETDZ, [65]) | |

| The municipal waste collection has been involved in recycling projects in the area. (Kawasaki Zero-Emission Industrial Complex, [39]) | ||

| In the park, the involved companies form groups that study and resolve social, environmental, and economic problems, which ultimately leads to strong public–private relationships that benefit both the companies and the local community. (Vreten Park, [68]) | ||

| The operator of the park liaises with the public authorities and other stakeholders. It has, for example, collaborated with a technological university to enhance the realization of IS in the park. (KIA, [62]) | ||

| The national environment agency worked together with the program to build awareness of IS. (NISP, [15]) | ||

| The local authorities have also participated directly in IS promotion. For example, the local government has organized a society of ecological companies. (REDA, [20]) | ||

| Policymaker | The local authorities and coordinating entities have tried to answer the needs and challenges of the park companies through sustainability policies, regulations, and programs. (Devens Eco-Industrial Park, [57]) | The park was established by the state legislature as an act to reuse the former military base. (Devens Eco-Industrial Park, [57]) |

| The program was the first national-level IS program in the world. The aim was to promote IS as a key policy tool for the industry and government to help the whole country reach a sustainable economy. (NISP, [15]) | The park is a result of the redevelopment aims of the local industrial properties initiated by the local municipality and supported by the federal government, the EU, and the local district. (Ecopark Hartberg GmbH, [58]) | |

| The frames for the EIP program were co-developed by the environmental protection agency of the city, state government, local university, community, and private sector constitutions. (Santa Cruz, [64]) | The park area has been allocated to companies by local authorities based on the aspect of leading environmental technologies and practices. (Kawasaki Zero-Emission Industrial Complex, [39]) | |

| The vital force for the redevelopment of the industrial area was the governmental eco-town program. The program aimed to ground innovative recycling actions within the aging conventional industry clusters. Under the program, the local government has guided the local industries toward more environmentally friendly actions. (Kawasaki Zero-Emission Industrial Complex, [39]) | ||

| The park became a national demonstration EIP, as it was selected by the national commission. (DDA, [21]) | ||

| The national guidelines create a frame based on which the management of the park has created its own guidelines to help accomplish the sometimes strictly binding national policy goals. (DDA, [21]) | ||

| The park was approved as a national eco-industrial demonstration park due to its good compliance with national policies. (Guitang Group, [60]) | ||

| The strong national policies toward pollution prevention and resource efficiency have guided the development agenda of the private park. (Nanning Sugar Co., Ltd., [63]) | ||

| The transformation of the park toward an eco-industrial one has been strongly led by national policies, according to which the management committee of the park has developed the park concept. Moreover, in the early phase, most of the IS performances were formed through the direct or indirect guidance of the governmental agenda. (REDA, [20]) | ||

| Alongside the national policies, the local city government has set its own policies for sustainability and designed its own implementation plans to develop CE within its area. (REDA, [20]) | ||

| The park has been established according to national economic and technological policies. There is a strong national agenda guiding the park. (SETDZ, [65]) | ||

| The national policies are accompanied by province-level policies, such as a fund for implementing cleaner production procedures in the companies. (SETDZ, [75]) | ||

| The park is part of an ongoing national development project, where the aim is to transfer traditional industrial parks into eco parks. The 15-year EIP plan has concrete steps according to which the industrial parks are being transformed. (Ulsan Eco-industrial Park, [67]) | ||

| Regulator | The park’s symbioses are to some extent the result of recycling-oriented thinking that has its grounding in the local legislative framework. (Kawasaki Zero-Emission Industrial Complex, [39]) | The main economic motives for the park companies to pursue IS are strict regulations, tax preferences, financial subsidies, and benefits from material substitution. (REDA, [20]) |

| The municipal government has accredited a committee to lead the development and management of the park. The committee does not have legislative rights, but it implements guidelines and policies in the park. (DDA, [21]) | The somewhat strict and demanding national legislation concerning the sustainable development of the sugar industry affects the actions of the park. (Guitang Group, [60]) | |

| In the park, there have been strong actions toward cleaner production in order to comply with the national legislation and maintain a good environmental image. (SETDZ, [65]) | ||

| There is a lot of regulation directly guiding the actions the park departments, especially the public ones, pursue. Overall, the regulation in the park has increased and become more demanding. It even pushes the companies to implement more environmentally friendly actions in their production. (SIP, [33]) | ||

| The national government has determined strict standards for the environmental quality of the industries in the park. (Ulsan Eco-industrial Park, [67]) | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uusikartano, J.; Väyrynen, H.; Aarikka-Stenroos, L. Public Agency in Changing Industrial Circular Economy Ecosystems: Roles, Modes and Structures. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310015

Uusikartano J, Väyrynen H, Aarikka-Stenroos L. Public Agency in Changing Industrial Circular Economy Ecosystems: Roles, Modes and Structures. Sustainability. 2020; 12(23):10015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310015

Chicago/Turabian StyleUusikartano, Jarmo, Hannele Väyrynen, and Leena Aarikka-Stenroos. 2020. "Public Agency in Changing Industrial Circular Economy Ecosystems: Roles, Modes and Structures" Sustainability 12, no. 23: 10015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310015

APA StyleUusikartano, J., Väyrynen, H., & Aarikka-Stenroos, L. (2020). Public Agency in Changing Industrial Circular Economy Ecosystems: Roles, Modes and Structures. Sustainability, 12(23), 10015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310015