A Sustainable Management Model for Cultural Creative Tourism Ecosystems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

- The president and founder of the Asociación de Comerciantes del Barrio de las Letras (The Association), a 66 year-old man, who has been an entrepreneur in the neighborhood for 35 years and owns one of the oldest shops. The topics addressed in this interview were trade in the neighborhood, local entrepreneur’s profiles, historical changes in neighborhood stores, goals, and commercial actions of the association.

- The general manager of The Association, a 49 year-old woman with a university degree. The subjects addressed were the goals, activities and commercial actions of the association, the responsibilities, and main managerial challenges of her position.

- Two additional founders of The Association: both male entrepreneurs, 45 and 48 years old, owners of a sports specialized store. The topics addressed with them were the reasons for the creation of the association, historical changes in the profiles of the entrepreneurs in the neighborhood, and the activities of The Association.

3. Results

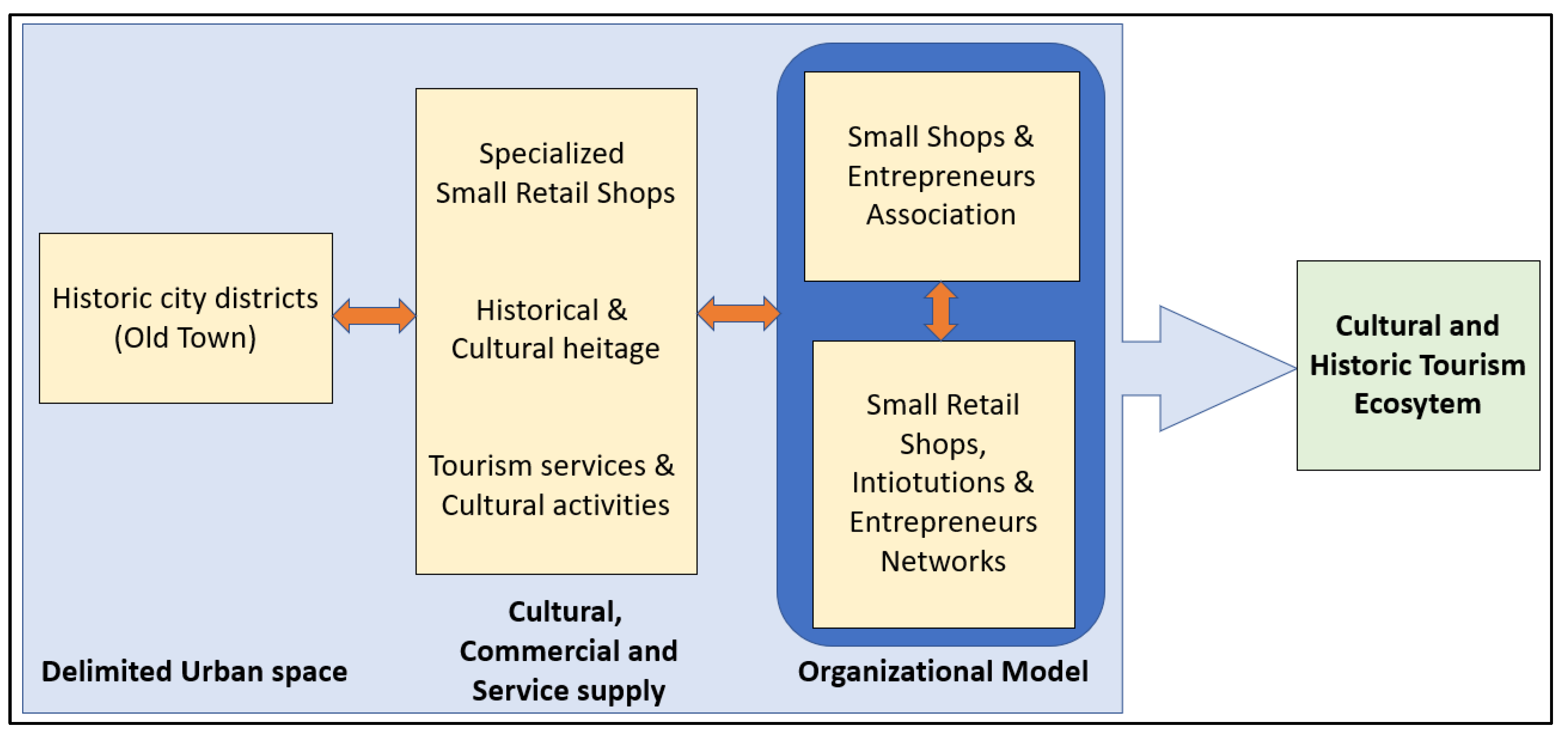

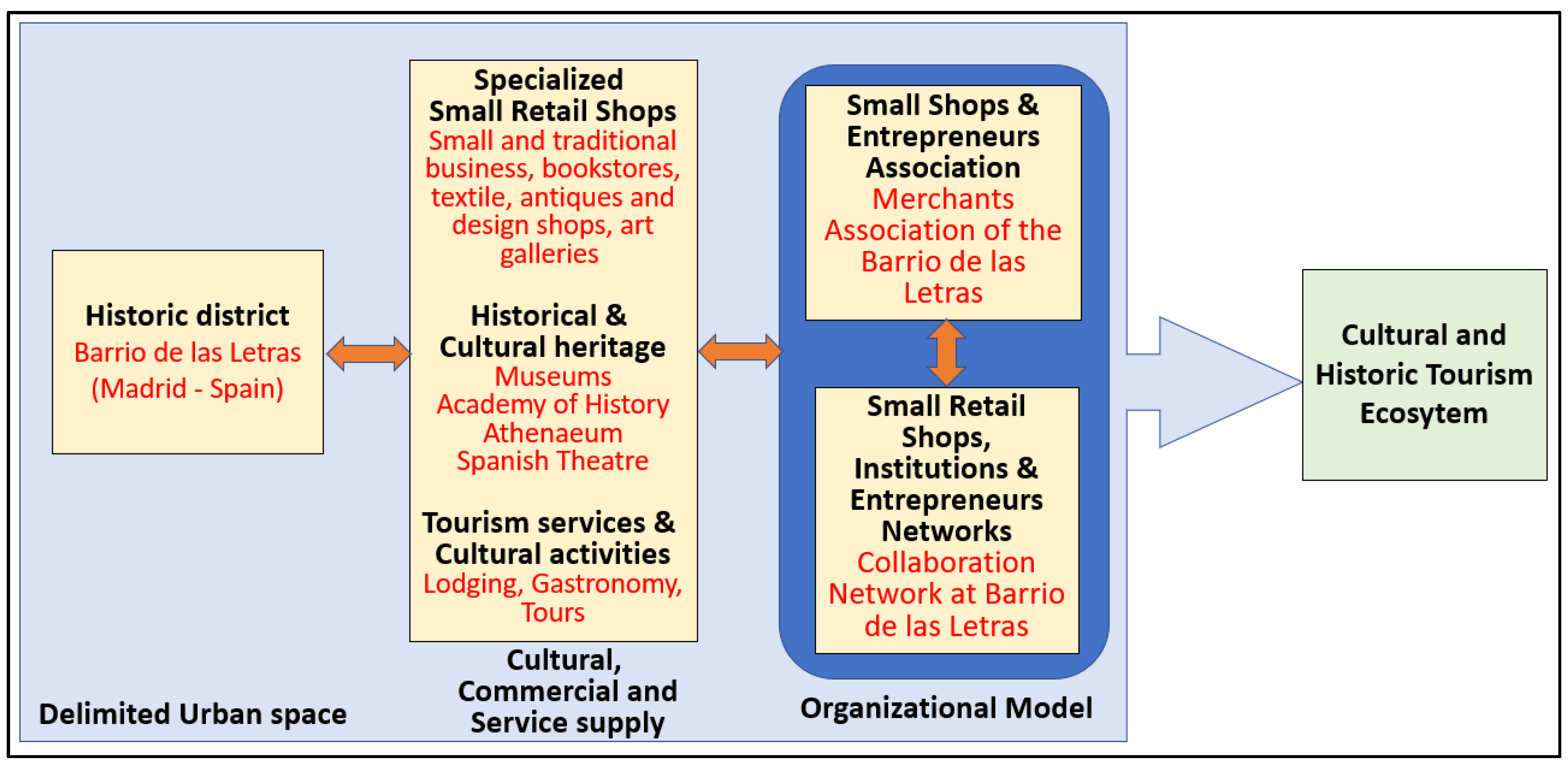

3.1. Management Model for City Centers with Historical and Cultural Identities: The Case of Barrio de las LetrasSubsection

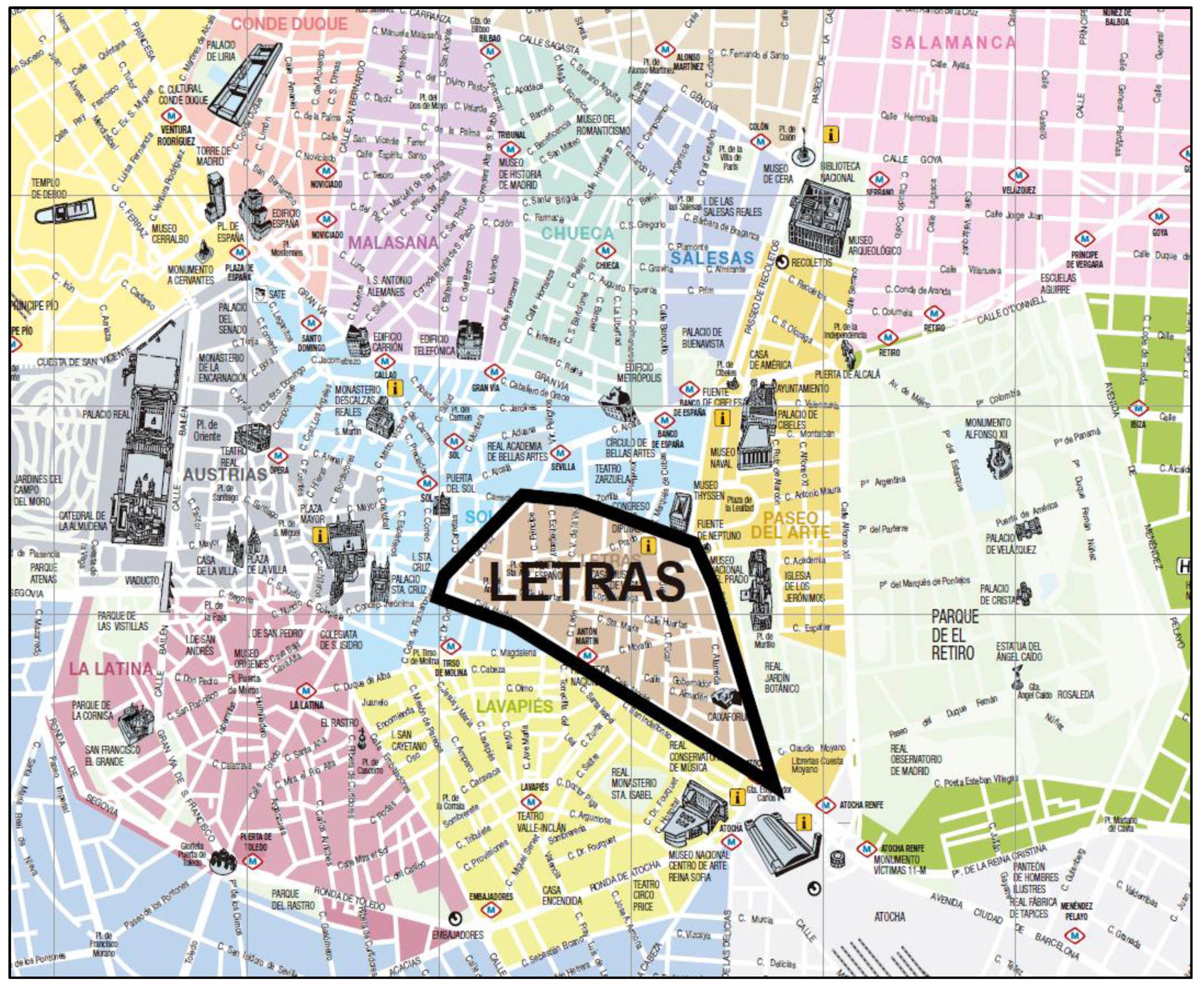

3.2. Delimited Urban Space in Barrio de las Letras

3.3. Cultural, Commercial, and Service Supply in Barrio de las Letras

- Specialized small retail. The influence of retail activity on the transformation of global cities is evident [69]; local and specialized shops have strategic value for their capacity to create unique environments that attract tourists. In some cities, the shopping streets are cultural objects, because of their specialized products. Specialized retail also might be associated with the historical and cultural identity of the district, such as the case of the “Centenary Stores of Madrid”; shops that are part of the living history of the city, protected and promoted in a Madrid tourism-sponsored guide, of which many are located in Barrio de las Letras. According to the data, the small retail segment consists of small commercial shops (95 respondents), with 35% dedicated to gastronomic services (67 respondents), 10% to diverse services (19 respondents), and 5% to lodging (9 respondents). The commercial establishments that create the identity of the neighborhood are mostly associated with history, art, and culture. The size of these businesses is small, with just an average of seven employees, though many businesses have just two or three employees. In our sample, 50% of the respondents to the questionnaire were the owners of the establishments, and the other 50% were employees who run the small businesses. In addition, 65.78% of the businesses are managed by people with university degrees, and 23.53% have secondary level. The deviation (16.76) stems from the hospitality and catering firms, which require more employees (around 20).

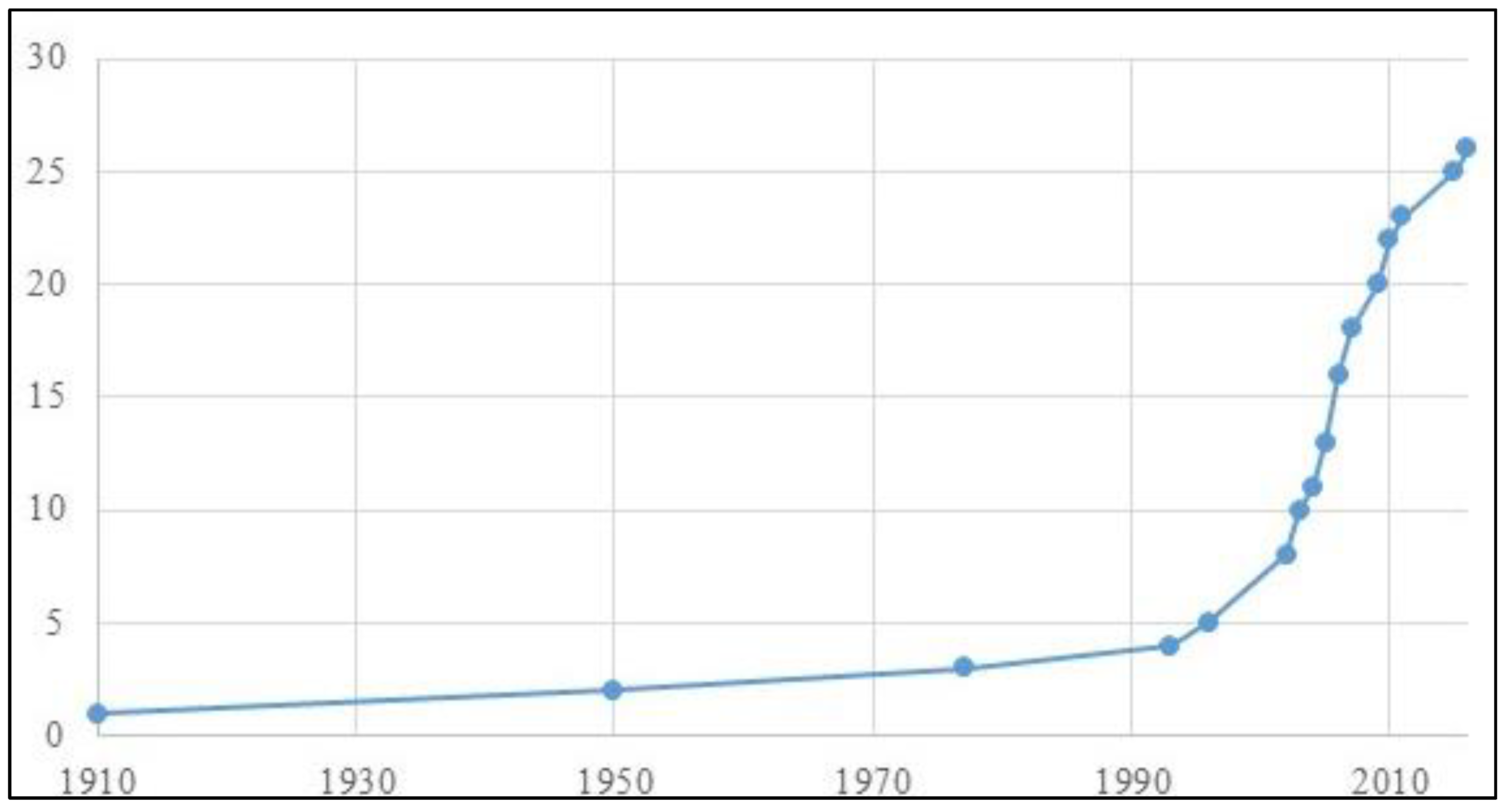

- Historic and cultural heritage. The local legacy is not necessarily associated with traditional tourist circuits, which highlight great monuments or visual icons that attract millions of visitors each year. Historic and cultural heritage instead constitute a strategic asset that is fundamental for developing cultural tourism and has a significant impact on destination brand equity [74,75,76] and includes tangible (e.g., museums, historical monuments, centenary stores) and intangible (e.g., routes, fairs, exhibitions, congresses, festivals) resources. “Heritage tourism is more “place-based” in that it creates a sense of place embedded in the local landscape, architecture, people, artefacts, traditions while cultural tourism is broadly concerned with the same types of experiences as heritage tourism, but at the same time less concerned with place” [77]. Intangible cultural heritage is a key means to differentiate cultural and historic destinations that benefit not only the socio-cultural life of visitors who are looking for unique experiences but also the inhabitants who live there [78]. Barrio de las Letras is a unique combination of heritage, cultural, and literary tourism. Literary tourism is associated with “places celebrated for literary depictions and/or connections with literary figures” [77]. Barrio de las Letras includes first-class historical and cultural offerings, such as the Prado Museum, Reina Sofía Arts Center, Caixa Forum, Lope de Vega and Cervantes House, and Ateneo de Madrid. With this cultural identity, the neighborhood is known for its unique “art strip”. Recent promotions of related cultural activities by these institutions have greatly increased the number of visitors (Table 3).

- Tourism services and cultural activities. Cities exposed to mass urban tourism need to find ways to decongest their traditional historic areas and promote new districts. Many and varied stakeholders participate in the reinvention of cultural and historic tourism, creating a mixture of top-down planned and emergent activities that seek to take advantage of the specialized retail offerings of the district, as well as the historical and cultural heritage already available there [40,80,81].

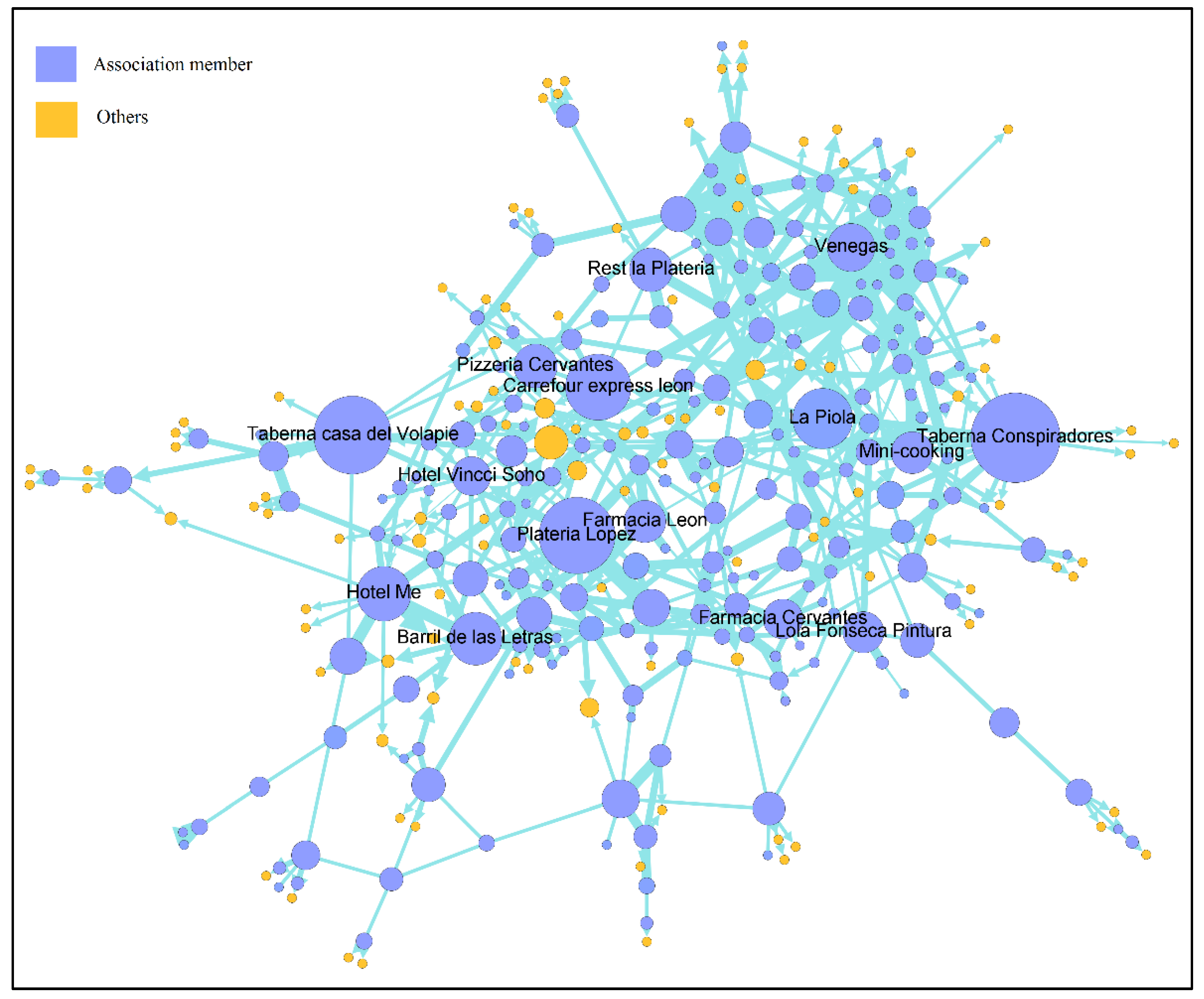

3.4. Management and Organizational Model

- Local associations of small retail shops and entrepreneurs. Associations have a leading role in revitalizing historical city areas [38,83]. Their members tend to be small businesses, looking for collaboration, the protection of their interests, and the creation of a reference group. Associations help coordinate entrepreneurs and small shops; identify new business and tourism opportunities [84]; and fulfill control functions, in that they devise ways to protect the identity of the district and differentiate it from traditional malls in suburbs [85]. Moreover, they often plan and implement changes to the commercial structures of historic districts, to enhance their attractiveness and visibility. Many studies accordingly demonstrate the relevance of interactions between public administrations and the association, to manage the commercial activity of urban areas jointly [37,84].

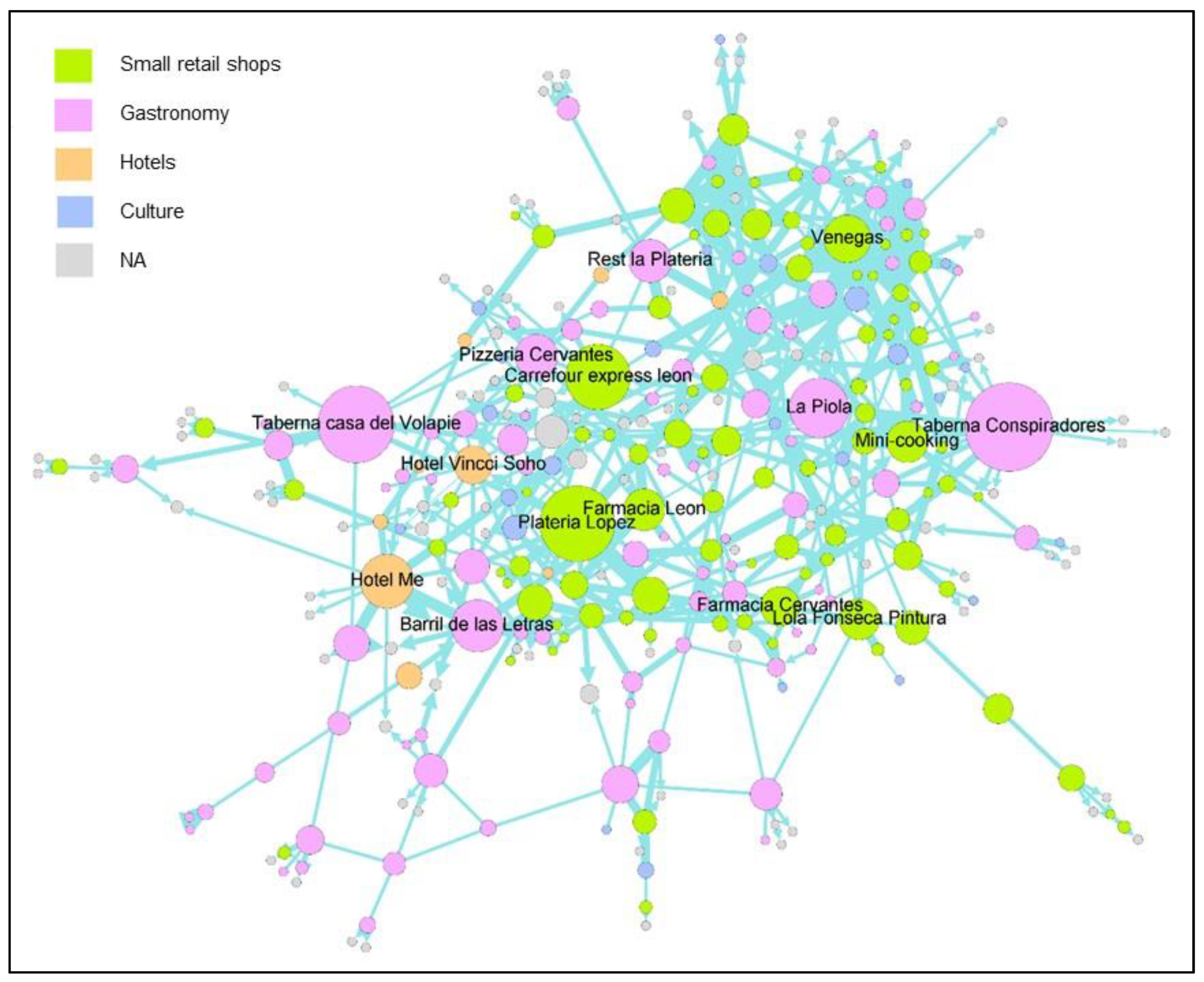

- Collaboration and social networks. Tourism is a critical industry, due to its vast potential to develop and improve regional competitiveness [65,86,87]. It is difficult to be competitive if regional stakeholders (public and private) are not involved, aligned, and collaborating [88]. Collaboration is essential to generate synergies and combine resources, which can then initiate virtuous cycles [40,86,89,90].

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Managerial Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashworth, G.; Page, S. Urban tourism research: Recent progress and current paradoxes. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTO. Tourism: 2020 Vision. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284404667 (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- WTO. Global Report on City Tourism. 2012. Available online: http://affiliatemembers.unwto.org/publication/global-report-city-tourism (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- WTO. Panorama OMT del Turismo Internacional. Available online: http://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/97892844181 (accessed on 19 October 2019).

- Garrod, B.; Dowell, D. Experiential Marketing of an Underground Tourist Attraction. Tour. Hosp. 2020, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhani, R. Understanding Private-Sector Engagement in Sustainable Urban Development and Delivering the Climate Agenda in Northwestern Europe. A Case Study of London and Copenhagen. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longley, A.; Duxbury, N. Introduction: Mapping cultural intangibles. Citycult. Soc. 2016, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.R. Museus, Turismo e Sociedade–uma reflexão. RITUR Rev. Iberoam. Tur. 2017, 7, 26–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagroba, M.; Szczepańska, A.; Senetra, A. Analysis and Evaluation of Historical Public Spaces in Small Towns in the Polish Region of Warmia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Naudin, J.; Vivas-Elias, P. La ciudad creativa y cultural como espacio de exclusión y segregación. Analizando La Placica Vintage de Zaragoza: Materialidades, prácticas, narrativas y virtualidades. EURE 2018, 44, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troitiño, M.A. El turismo en las ciudades históricas. Polígonos. Rev. Geogr. 1995, 5, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troitiño, M.A. Turismo y desarrollo sostenible en las ciudades históricas con patrimonio arquitectónico monumental. Estud. Turísticos 1998, 137, 5–53. [Google Scholar]

- Troitiño, M.A. Turismo, patrimonio y recuperación urbana en ciudades y conjuntos históricos. Patrim. Cult. España 2012, 6, 147–185. [Google Scholar]

- Troitiño, M.A. Las ciudades patrimonio de la humanidad de España: El desafío construir destinos turísticos sostenible en clave de patrimonio cultural. Estud. Turísticos 2018, 216, 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Exceltur. Available online: http://www.exceltur.org/ (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Madrid Destino. Available online: http://madrid-destino.com/es (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Tuespaña. Available online: https://www.tourspain.es/es-es (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Murphy, P. Tourism: A Community Approach; Methuen: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- García, J.S.; Troitiño Vinuesa, M.A. Vivir las Ciudades Históricas: Recuperación Integrada y Dinámica Funcional; Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Colección Estudios: Madrid, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce, G. Geografía urbana: Nuevos retos y complejidad del fenómeno urbano. In Geografía Humana. Fundamentos, Métodos y Conceptos; Editorial Club Universitario: Alicante, Spain, 2002; pp. 119–150. [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra, D.; Healy, R.; Sills, E. Staged authenticity and heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchena, J.M. Patrimonio y Ciudad: Nuevos Escenarios de Promoción y Gestión del Turismo Urbano Europeo; Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes: Alicante, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.Y. Heritage Tourism. Emotional Journeys into Nationhood. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Page, S. Destination marketing organizations and destination marketing: A narrative analysis of the literature. Tour. Manag. 2013, 41, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Place branding and city centre management: Exploring international parallels in research and practice. J. Urban Reg. Renew. 2014, 7, 363–369. [Google Scholar]

- González, P. Authenticity as a challenge in the transformation of Beijing´s urban heritage: The commercial gentrification of the Guozijian historic area. Cities 2016, 59, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, F.; Font, X.; Ivanova, M. Creating shared value in destination management organizations: The case of Turisme de Barcelona. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Bramwell, B.; Whalley, P.A. Cultural political economy and urban heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 68, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, C.; Coll, V.; Rausell-Köster, P.; Pérez Yábar, D. Cultural attitudes and tourist destination prescription. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 71, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Nuevos Caminos Para el Turismo Cultural? Available online: www.diba.es/cerc/arxinterac04/arcem1/richards/dipbarcelona (accessed on 27 June 2020).

- Canalis, X. Destinos Hípster, la Tendencia Para Mitigar el Turismo Masivo. Available online: https://www.hosteltur.com/115250_destinos-hipster-tendencia-mitigarturismo-masivo.html (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Valente, F.; Dredge, D.; Lohmann, G. Leadership and governance in regional tourism. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.G.; Barth, M. Learning Processes in the Early Development of Sustainable Niches: The Case of Sustainable Fashion Entrepreneurs in Mexico. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naef, P. Resilience as a City Brand: The Cases of the Comuna 13 and Moravia in Medellin, Colombia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakar, K. Critical success factors for tourist destination governance in times of crisis: A case study of Antalya, Turkey. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 786–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zach, F.; Hill, T.L. Network, knowledge, and relationship impacts on innovation in tourism destinations. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaterina, J.; Zorrilla, P. Encouraging the implication of shops in the city by means of retail associationism. The case of Bilbao. Cuad. Gest. 2005, 5, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Coca-Stefaniak, J.A.; Parker, C.; Quin, S.; Rinaldi, R.; Byrom, J. Town center management models: A European perspective. Cities 2009, 26, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinillo, S. Centros comerciales de área urbana. Estudio de las principales experiencias extranjeras. Distrib. Consum. 2001, 57, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaboldi, M.; Spiller, N. Actor-network theory and stakeholder collaboration: The case of cultural districts. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M. Entidades de planificación y gestión turística a escala local. El caso de las Ciudades Patrimonio de la Humanidad en España. Cuad. Tur. 2007, 20, 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D. Tourist districts in Paris: Structure and functions. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merinero-Rodríguez, R.; Pulido-Fernández, J.I. Analyzing relationships in tourism: A review. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Merinero-Rodríguez, R. Destinations’ relational dynamic and tourism development. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2016, 7, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Zee, E.; Vanneste, D. Tourism networks unraveled; a review of the literature on networks in tourism management studies. Tour. Manag. 2015, 15, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henche, B.G.; Salvaj, E. Barrio de Las Letras: Turismo, Comercio y Cultura. Asociacionismo y Estrategias de Comercialización de un barrio en transformación. Cuad. Tur. 2017, 40, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.; Hardyman, R. Place marketing and town centre management. A new tool for urban revitalization. Cities 1996, 13, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.; Wallis, J. Business Improvement Districts, a Guide to Establishing a BID in Massachusetts; Massachusetts Department of Housing & Community Development: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Applebaum, W. Evaluating store sites and determining store rents. Ecol. Geogr. 1960, 36, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizagárate, V. Marketing de Ciudades: Estrategias Para el Desarrollo de Ciudades Atractivas y Competitivas en un Mundo Global; Editorial Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Haider, D.H.; Rein, I. Marketing Places: Attracting Investment, Industry and Tourism to Cities, States and Nations; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, P.C.; Pereira Roders, A.R.; Colenbrander, B.J.F. Measuring links between cultural heritage management and sustainable urban development: An overview of global monitoring tools. Cities 2017, 60, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siow-Kian, T.; Shiann-Far, K.; Ding-Bang, L. A model of creative experience in creative tourism. Tour. Res. 2013, 41, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Creative tourism: Opportunities for smaller places? Tour. Manag. Stud. 2019, 15, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeça, S.; Gonçalves, A.R.; Marques, J.F.; Tavares, M. Mapping intangibilities in creative tourism territories through tangible objects: A methodological approach for developing creative tourism offers. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2019, 15, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Huang, S.; Fu, H. An application of network analysis on tourist attractions: The case of Xinjiang, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovich, K. The evolution and transformation of a tourism destination network: The Waitomo Caves, New Zealand. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.; Cooper, C.; Baggio, R. Destination networks: Four Australian cases. A. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisi, H.; Baggio, R.; Barratt-Pugh, L.; Willson, G. A network perspective of knowledge transfer in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 80, 102817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeri, M.; Baggio, R. Italian tourism intermediaries: A social network analysis exploration. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareti, S.; García Henche, B.; Salvaj, E. Dinamización de los barrios históricos hacia destinos de turismo experiencial. Papel de las redes de colaboración en la estimulación del Barrio de las Letras en Madrid y Barrio Italia en Santiago de Chile. Polígonos Rev. Geogr. 2018, 30, 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Novelli, M.; Schmitz, B.; Spencer, T. Networks, clusters and innovation in tourism: A UK experience. Tour. Manag. 2005, 27, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czakon, W.; Czernek, K. The role of trust-building mechanism in entering into network coopetition: The case of tourism networks in Poland. Indus. Mark. Manag. 2016, 57, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeri, M.; Baggio, R. Social network analysis: Organizational implications in tourism management. Int. J. Org. Anal. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, V.; Varajão, J.; Oliveira, P. Cooperation Networks in the Tourism Sector: Multiplication of Business Opportunities. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 64, 1172–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, M.; Armelini, G.; Salvaj, E. Understanding Social Contagion in Adoption Processes Using Dynamic Social Networks. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, R.; Parker, A. The Hidden Power of Social Networks; Harvard Business School Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Elizagarate, V. La ciudad centro comercial abierto: Un modelo con nuevas oportunidades para el comercio tradicional de los municipios y comarcas de Guipúzkoa. Rev. Dir. Adm. Empresas 2001, 9, 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro, A.; Marques, J.F. Visita Guiada à Fábrica de Antiguidades: Sociologia, Turismo e Autenticidade. Rev. An. Bras. Estud. Turísticos ABET 2017, 7, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría, J. Centros históricos: Análisis y perspectivas desde la Geografía. GeoGraphos 2013, 4, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turismo de Madrid. Available online: https://www.esmadrid.com/en/tourist-areas-map (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Asociación de Comerciantes Barrio de las Letras. Available online: www.barrioletras.com (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Martin, F. Turismo y economía en las ciudades históricas españolas. Ería 1998, 47, 267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Duarte, P.; Folgado-Fernández, J.A. The contribution of cultural events to the formation of the cognitive and affective images of a tourist destination. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kladou, S.; Kehagias, J. Assessing destination brand equity: An integrated approach. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2014, 3, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppen, A.; Brown, L.; Fyall, A. Literary tourism: Opportunities and challenges for the marketing and branding of destinations? J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2014, 3, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Calle, M. La Ciudad Histórica Como Destino Turístico; Ariel Turismo: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuntamiento de Madrid. Available online: www.madrid.es/portales/munimadrid (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Mora, D. Reinventando Ciudades y Recursos Turísticos. Available online: https://www.hosteltur.com/158060_turismo-experiencias-se-reinventa-destinos-urbanos.html (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- Skandalis, A.; Byrom, J.; Baister, E. Experiential marketing and the changing nature of extraordinary experiences in post-postmodern consumer culture. J. Business Res. 2019, 97, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinillo, S.; Japutra, A. Factors influencing domestic tourist attendance at cultural attractions in Andalusia, Spain. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filion, P.; Hoerning, H.; Buting, T.; Sands, G. The successful few. Healthy downtowns of small metropolitan regions. J. Am. Plan. Ass. 2004, 70, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azón, J.; Huarte, M.; Pelegrin, J. Asociacionismo comercial y cooperación en el comercio detallista. In Conocimiento, Innovación y Emprendedores: Camino al Futuro; Universidad de la Rioja Ediciones: Logroño, Spain, 2007; pp. 2267–2280. [Google Scholar]

- Medway, D.; Ebennio, D.; Alexander, A. Reasons of retailers’ involvement in town centre management. Inter. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2000, 28, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, F.; Giusti, J. Cultural heritage, tourism and regional competitiveness: The Motor Valley cluster. Citycult. Soc. 2012, 3, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehrer, A.; Raich, F.; Siller, H.; Tschiderer, F. Leadership networks in destinations. Tour. Rev. 2014, 69, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H. Network characteristics of drive tourism destinations: An application of network analysis in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Alletorp, L. Attitudes in the Danish tourism industry to the roles of business and government in sustainable tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2001, 3, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graci, S. Collaboration and Partnership Development for Sustainable Tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2013, 15, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Laboratorio para Ciudad de México. Innovación Participativa en el Distrito Federal. Basediseño E Innovación 2016, 3, 26–47. [Google Scholar]

- D’Angella, F.; Go, F.M. Tale of two cities’ collaborative tourism marketing: Towards a theory of destination stakeholder assessment. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkhorst, E. Turismo de co-creación, valor añadido en escenarios turísticos. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 1, 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, T.; Hubbard, P. The entrepreneurial city: New urban politics, new urban geographies. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1996, 20, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.K.; Kung, S.F.; Luh, D.B. A model of ‘creative experience’ in creative tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 41, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohridska-Olson, R.; Ivanov, S.; Creative Tourism Business Model and its Application in Bulgaria. Proceedings of the Black Sea Tourism Forum ‘Cultural Tourism—The Future of Bulgaria’. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1690425 (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Cabeça, S.; Gonçalves, A.R.; Marques, J.F.; Tavares, M. Creative tourist experiences in low- density territories: Valuing the Algarve´s Inland. In Creative Tourism Dynamics: Connecting Travellers, Communities, Cultures, and Places. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/44135232/Creative_Tourism_Experiences_in_Low_Density_Territories_Valuing_the_Algarve_s_Inland (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Richards, G. Designing creative places: The role of creative tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Universe | Commercial and Cultural Organizations. Barrio de las Letras |

|---|---|

| Geographical Area | Barrio de las Letras—Madrid |

| Sample | 187 valid surveys (of the 301 associates businesses) |

| Sampling Procedure | Convenience sampling, setting a confidence level of 95% and corresponding to a level of significance of 5% |

| Sample Error | According to the sample size used, the maximum permissible error (for an estimation of proportions) is assumed to be +/- 4% under conditions of maximum uncertainty (p = q = 50%) |

| Technique of collection of the information | Managed personal survey with structured questionnaire |

| Period of collection of information | January–July 2016 |

| Information processing | Univariate and descriptive bivariate analysis with Dyane, SPSS 12.0. and Excel. Social network analysis with Gephi |

| Shops | Frequency (95) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Antiquities | 9 | 9.47% |

| Food | 8 | 8.42% |

| Art | 15 | 15.79% |

| Flowers and plants | 1 | 1.05% |

| House and decoration | 6 | 6.32% |

| Musical instruments | 1 | 1.05% |

| Book shops | 6 | 6.32% |

| Fashion and Apparel | 20 | 21.05% |

| Health | 2 | 2.11 |

| Jewelry and costume | 3 | 3.16% |

| Printing and graphic arts | 1 | 1.05% |

| Other commercial activities | 12 | 12.63% |

| Repair and sale of motorcycles | 1 | 1.05% |

| Restaurants/Catering | Frequency (67) | Percentage |

| Restaurants and catering | 67 | 35% |

| Lodging | Frequency (9) | Percentage |

| Restaurants and catering | 67 | 35% |

| Hotels | 6 | 66.67% |

| Hostels | 1 | 11.11% |

| Others | 2 | 22.22% |

| Services | Frequency (19) | Percentage |

| Beauty | 2 | 10.53% |

| Teaching | 1 | 5.26% |

| Gym and Spa | 1 | 5.26% |

| Real State | 3 | 15.79% |

| Health and Sanitary centers | 1 | 5.26% |

| Leisure and Free time | 1 | 5.26% |

| Other services | 10 | 52.63% |

| Beauty | 2 | 10.53% |

| Museum | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prado | 2.732 | 2.912 | 3.157 | 2.516 | 2.754 | 2.697 | 3.034 | 2.824 | 2859 |

| Reina Sofía | 2.414 | 2.706 | 2.572 | 3.185 | 2.677 | 3.257 | 3.745 | 3.896 | 1694 |

| Lope de Vega | 21 | 22 | 22 | 42 | 64 | 84 | 106 | 90.2 | 151 |

| Caixa Forum | - | 1.000 | 904 | 764 | 768 | 568 | 568 | 623 | 947 |

| MADRID | 9.521 | 11.513 | 11.835 | 11.653 | 12.445 | 13.083 | 13.723 | 10.756 | 16.448 |

| Commercial Actions | Advertising Poster | Participation of Members of the Association |

|---|---|---|

| DecorAcción |  | 112 (59%) |

| The Frog Market |  | 116 (62%) |

| The Night of Books |  | 25 (13%) |

| Black Friday |  | 65 (34%) |

| Betweenness | Name | Degree | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.11 | Taberna Conspiradores | 19 | Taberna Conspiradores |

| 0.10 | Taberna Casa Del Volapie | 19 | Venegas |

| 0.09 | Platería López | 19 | Érase Una Vez. |

| 0.08 | Carredour Express Leon | 17 | Valyrium |

| 0.07 | Restaurante A’cañada | 13 | Taberna Casa Del Volapie |

| 0.06 | Hotel Me | 13 | Platería López |

| 0.06 | El Barril De Las Letras | 13 | Hotel Me |

| 0.05 | Venegas | 13 | Ginger & Velvet |

| 0.05 | Pizzería Cervantes | 13 | Miseria |

| 0.05 | La Platería | 12 | Hotel Vincci Soho |

| 0.05 | Farmacia León | 12 | Mazarias |

| 0.05 | Mini-Cooking | 12 | Motteau |

| 0.04 | Lola Fonseca Pintura En Seda | 12 | Il Guacciaro |

| 0.04 | Farmacia Cervantes | 11 | Losada |

| 0.04 | Hotel Vincci Soho | 11 | Droguería Pefu Castillo |

| 0.04 | Restaurante Matute | 10 | Carrefour Express Leon |

| 0.04 | Olarra | 10 | Pizzería Cervantes |

| 0.04 | Naturbier | 10 | Mini-Cooking |

| 0.04 | Librería Del Prado | 10 | Olarra |

| 0.04 | Ginger & Velvet | 10 | Bodegas Trigo |

| 0.04 | Restaurante Matute | 10 | Carrefour Express Leon |

| 0.04 | Olarra | 10 | Pizzería Cervantes |

| 0.04 | Naturbier | 10 | Mini-Cooking |

| 0.04 | Librería Del Prado | 10 | Olarra |

| 0.04 | Ginger & Velvet | 10 | Bodegas Trigo |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Henche, B.G.; Salvaj, E.; Cuesta-Valiño, P. A Sustainable Management Model for Cultural Creative Tourism Ecosystems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229554

Henche BG, Salvaj E, Cuesta-Valiño P. A Sustainable Management Model for Cultural Creative Tourism Ecosystems. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229554

Chicago/Turabian StyleHenche, Blanca García, Erica Salvaj, and Pedro Cuesta-Valiño. 2020. "A Sustainable Management Model for Cultural Creative Tourism Ecosystems" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229554

APA StyleHenche, B. G., Salvaj, E., & Cuesta-Valiño, P. (2020). A Sustainable Management Model for Cultural Creative Tourism Ecosystems. Sustainability, 12(22), 9554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229554