The Urban Museum as a Creative Tourism Attraction: London Museum Lates Visitor Motivation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Museums as a Cultural and Creative Tourism Attraction and Sustainability

2.2. Special Events During Late Hours in Museums

2.3. Museum Visitor Motivation Research

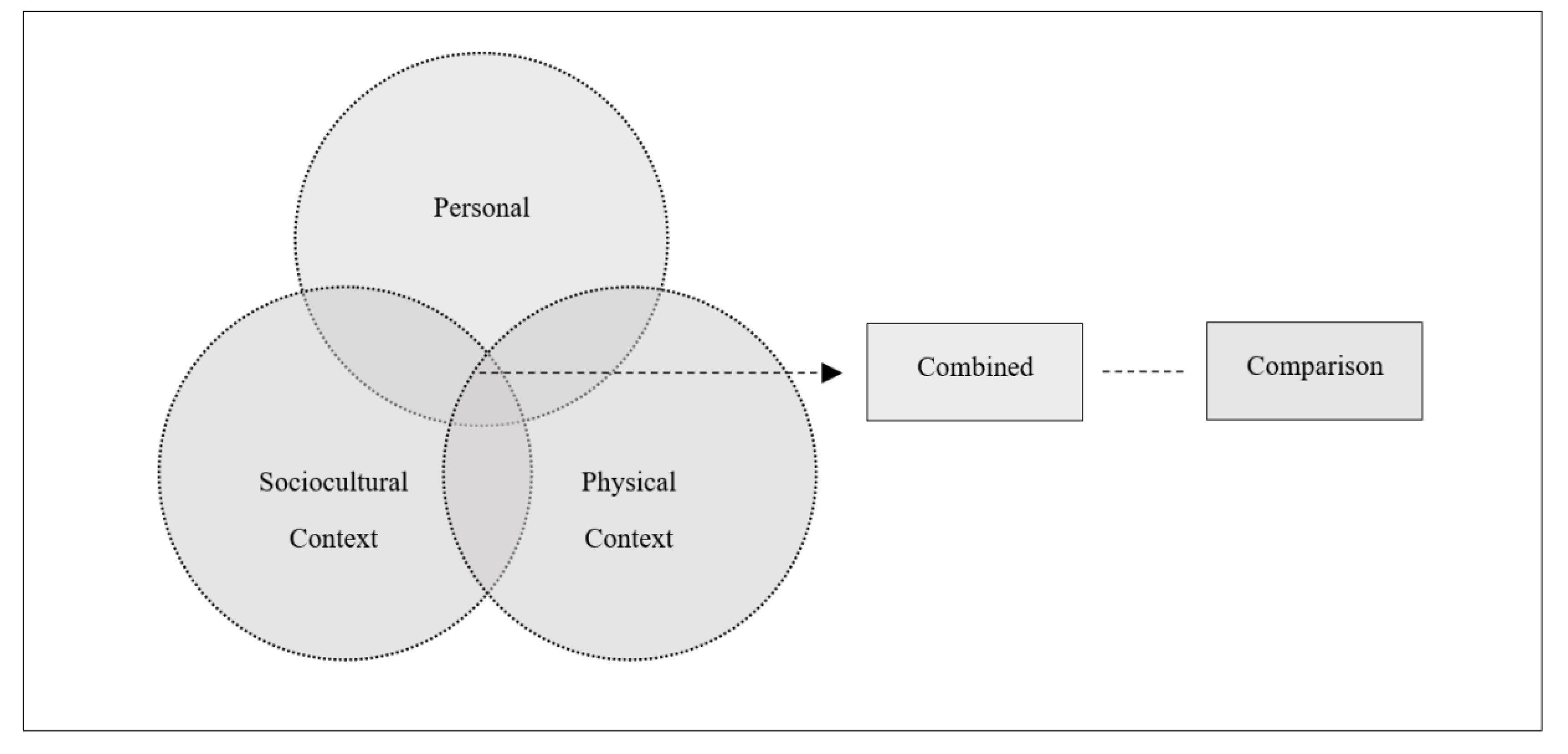

2.4. The Contextual Model of Learning to Determine Visitor Motivation

2.4.1. Personal Context

2.4.2. Social Context

2.4.3. Physical Context

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Aim and Questions

- How can visitors be comprehended with identity-related motivational factors?

- What are the motivational factors for visitors to visit the Museum Lates?

- How are the motivations different compared with other daily activities and exhibitions?

- How are the motivations different compared with day-time and late-hour visits?

- Why are the Museum Lates significant for museums as multi-functional institutions in enhancing the long-term goal of sustainability?

3.2. Qualitative Methodology Approach

3.3. The Interview Guidelines and Pilot Study

3.4. Research Scope and Sampling

3.5. Data Collection

3.6. The Analysis

4. Findings and Analysis

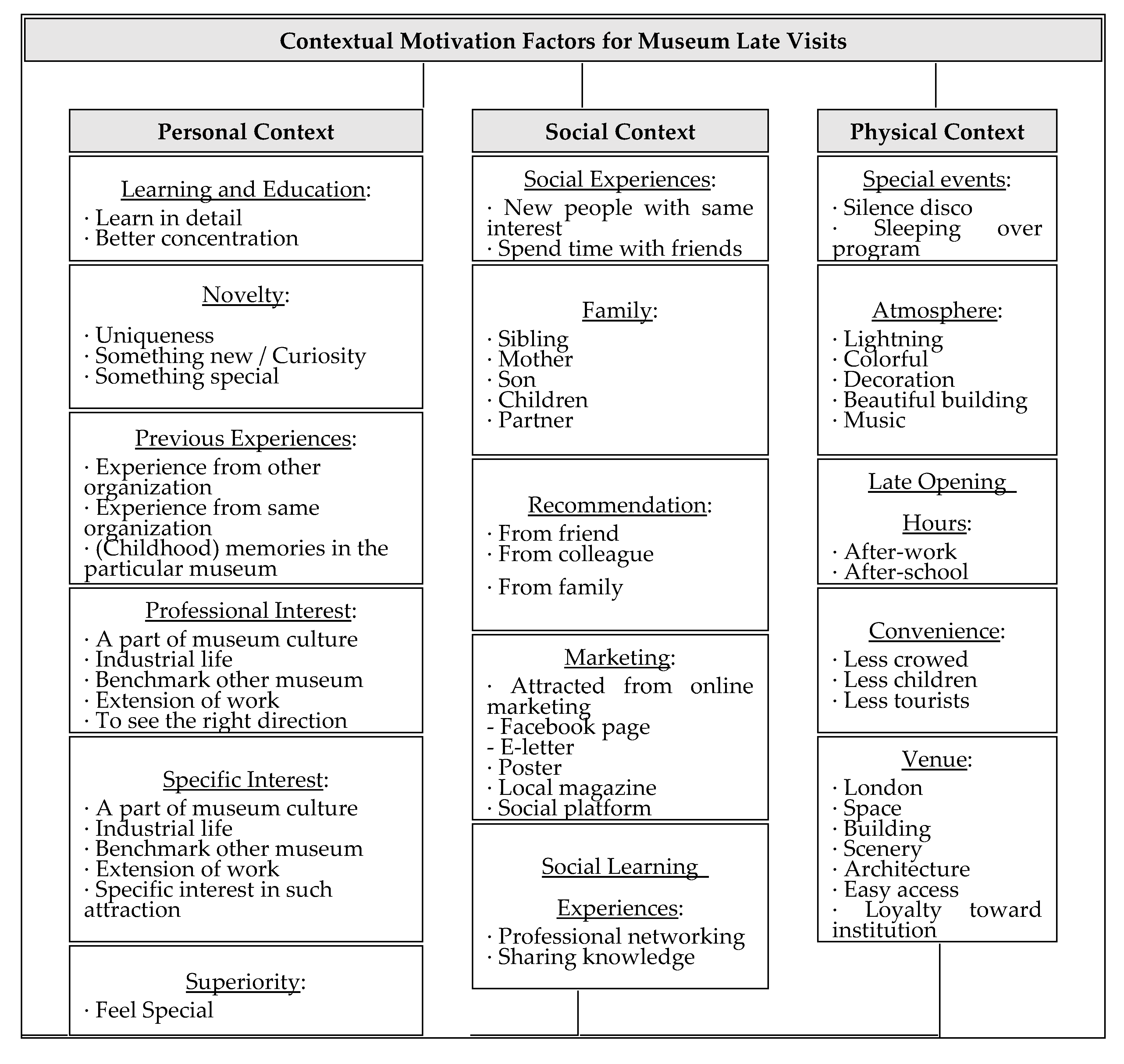

4.1. Contextual Motivational Factors

4.1.1. Personal Context

“…I was brought here as a child and I had such good memories… that to come back as an adult and spend a night here is truly magical.”

4.1.2. Sociocultural Context

4.1.3. Physical Context

“(…) normally the opening hours of museum are very close to when I work, so I don’t get much time to go to museums during the day.”

4.1.4. Combination and Complexity

4.1.5. Other Daily Activities and Exhibitions

“The Lates are a great way to open our door to people who are interested in learning more about the museum and what is happening here; day to day, it is a quite different setting (…)”

“So, for me, tonight is more about enjoying the space, but not necessarily seeing the exhibitions. It’s a beautiful building, so I’ll have a drink with my sister and catch up in beautiful scenery.”

4.1.6. Daytime

“(…) the atmosphere is just not that educational, you know, the lighting is so colorful and the decoration and people talk and laugh; it is just more entertainment, it is not that educational” (R-21).

“(…) I think that’s the main point (nodding). It made the museum night special (…) It is not really common for a museum to be opened during nighttime, so it makes [the event] more special, the event in the nighttime. I think I prefer during nighttime because maybe I am a student, so I after a full day of study or if I am working, you know, [I will] definitely want to do something with my friends and want to be relaxed, yes uh huh (nodding).”

“Daytime events are quite structured, quite short (…) the level of depth of engagement is different. (…) the topics and contents are the same, but running hours and the level of engagement is different”.

4.2. Museums as Multi-Functional Institutions to Enhance the Future Sustainability

“Though I came during the night and had drinks, educational and professional reasons come preferentially.” Similarly, there was a mention of the multi-functionality of museums by R-11: “Attracting is important, but education is more crucial.”

“I think people’s expectation is constantly growing… some people do not consider, not everyone but, as the same old dusty institutions they used [be], they are much more open, places to talk, discuss ideas… I think people see them as almost like a theme park or a festival, so our events are also almost considered to be in the bracket as well; the field is completely as open as the next, a museum can be anything.”

“I guess [the museum’s role is] a part for preservation and a part for utilization, isn’t it? And sort of, yes, comes together as well.”

4.3. Museum Lates as a Motivation

4.4. The Importance of Museum Lates

“…um, everything really does with that, um, generating income, generating some revenue for the museum as well through tickets…it is needed for the institution, but we do not expect big profits from the event.”

“They primarily started as another way of engaging different audiences that wouldn’t come naturally during the day or on the weekend to do something fun that’s interesting, that’s exciting, for a completely new market segment (…) They are an amazing, more fun time to get closer to the public” (EC-1).

“(…) I would say in terms of the rest of our events. Currently, our objectives are around, as Eszter said, developing new audiences and engaging them with our sites and the collections…I would definitely say, across the events, we are targeting similar but slightly different people to bring into the museum… inspiring people for learning… It is a good hook; some might not be coming otherwise” (EC-2).

“Cool events are crucial for current museums to hook visitors to come back. Simply drinking and partying can hardly lead to revisiting of consumers” (R-2).

“If [they] always have the same things, you don’t want to come more than once, I think. If you change something and [they] give something new, people would like to come again, maybe” (R-11). R-28 also mentioned Museum Lates as a “marketing” method of museums.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pencarelli, T.; Cerquetti, M.; Splendiani, S. The sustainable management of museums: An Italian perspective. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 22, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertacchini, E.E.; Dalle Nogare, C.; Scuderi, R. Ownership, organization structure and public service provision: The case of museums. J. Cult. Econ. 2018, 42, 619–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worts, D. Measuring Museum Meaning. J. Mus. Educ. 2006, 31, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, G.C.; Worts, D.; Janes, R.R.; Conaty, G. Looking Reality in the eye: Museums and social responsibility. In Negotiating a Sustainable Path: Museums and Societal Therapy; University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2005; p. 129. [Google Scholar]

- Easson, H.; Leask, A. After-hours events at the National Museum of Scotland: A product for attracting, engaging and retaining new museum audiences? Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 23, 1343–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, P.; Leask, A. Visitor engagement at museums: Generation Y and ‘Lates’ events at the National Museum of Scotland. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2017, 32, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordin, V.; Dedova, M. Cultural Innovation and Consumer Behaviour: The Case of Museum Night. Int. J. Manag. Cases 2014, 16, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bjeljac, Z.; Brankov, J.; Lukić, V. The ‘Museum Night’ Event—The Demographic Profile of the Visitors in Serbia. Forum Geogr. 2011, 10, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinghorn, N.; Willis, K. Measuring Museum Visitor Preferences towards Opportunities for Developing Social Capital: An Application of a Choice Experiment to the Discovery Museum. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2008, 14, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museumsatnight.org.uk. What’s on | Museums at Night. 2019. Available online: http://museumsatnight.org.uk/whats-on/#.VxOBgfkrKM8 (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Nhm.ac.uk. Lates | Natural History Museum. 2019. Available online: http://www.nhm.ac.uk/visit/exhibitions/lates.html (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- Tate. Late at Tate Britain. 2019. Available online: http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/late/late-tate-britain (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- Sciencemuseum.org.uk. Lates. 2019. Available online: http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/visitmuseum/plan_your_visit/lates (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Vam.ac.uk. Friday Late—Victoria and Albert Museum. 2019. Available online: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/f/friday-late/ (accessed on 18 April 2019).

- Mavrin, I.; Glavaš, J. The Night of the Museums Event and Developing New Museum Audience– Facts and Misapprehensions on a Cultural Event. Interdiscip. Manag. Res. 2014, 10, 265–274. [Google Scholar]

- Tansuchat, R.; Panmanee, C. Tourist Motivation, Characteristic, and Satisfaction in Night Festival: Loykrathong Festival; School of Tourism Development-Maejo University, Thailand and Asian Tourism Management Association: Chiangmai, Thailand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Axelsen, M. Using Special Events to Motivate Visitors to Attend Art Galleries. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2006, 21, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H. Understanding Museum Visitors’ Motivations and Learning. Available online: https://slks.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/dokumenter/KS/institutioner/museer/Indsatsomraader/Brugerundersoegelse/Artikler/John_Falk_Understanding_museum_visitors__motivations_and_learning.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Foster, S.; Fillis, I.; Lehman, K.; Wickham, M. Investigating the relationship between visitor location and motivations to attend a museum. Cult. Trends 2020, 29, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsen, M. Visitors’ Motivations to Attend Special Events at Art Galleries: An Exploratory Study. Visit. Stud. 2007, 10, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, A. Motivations for Visiting and not Visiting Museums Among Young Adults: A Case Study on uum Students. J. Glob. Manag. 2011, 3, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson: Harlow (Essex), UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.R. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. Am. J. Evaluation 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. The Museum Experience; Whalesback Books: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Freeland, C. But is It Art? Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez, A.V.; Tsutsui, N.D. The value of museum collections for research and society. BioScience 2004, 54, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cima, J. Private Events, Public Spaces: Why Guests Choose Museums as Hosting Sites a Case Study at the Museum of Flight. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, C. Museum and art gallery experience space characteristics: An entertaining show or a contemplative bathe? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, P.; Wolff, A.; Collins, T.; Zdrahal, Z. An event-based approach to describing and understanding museum narratives. In Proceedings of the Detection, Representation, and Exploitation of Events in the Semantic Web Workshop in conjunction with the International Semantic Web Conference, Bonn, Germany, 23 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. Changing Values in the Art Museum: Rethinking communication and learning. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2000, 6, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, G.E. Learning in the Museum; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Deborah, W. Museum Archives: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; Society of American Archivists: Chicago, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Aalst, V.; Boogaarts, I. From Museum to Mass Entertainment: The Evolution of the Role of Museums in Cities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2002, 9, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Event Management & Event Tourism, 2nd ed.; Cognizant Communication Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, D. Special Event Production. The Process; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Packer, J.; Ballantyne, R. Motivational factors and the visitor experience: A comparison of three sites. Curator Mus. J. 2002, 45, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, J. Measuring total customer experience in museums. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Mngt. 1999, 11, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christianson, M.; Farkas, M.; Sutcliffe, K.; Weick, K. Learning through Rare Events: Significant Interruptions at the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 846–860. [Google Scholar]

- Templeton, C.A. Museum Visitor Engagement through Resonant, Rich and Interactive Experiences. Ph.D. Thesis, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, K. Movement and Theater in the Art Museum. Master’s Thesis, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Belenioti, C.; Vassiliadis, C. Branding in the New Museum Era. In Strategic Innovative Marketing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, N.; Kotler, P. Can Museums be All Things to All People? Missions, Goals, and Marketing’s Role. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2000, 18, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, H. Arts, Entertainment and Tourism; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen-Verbeke, M.; Van Rekom, J. Scanning museum visitors. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriman, N. Museum collections and sustainability. Cult. Trends 2008, 17, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. Museum Experience Revisited; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hein, G.E. The Role of Museums in Society: Education and Social Action. Curator: Mus. J. 2005, 48, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Lin, F. Exploring Visitors’ Experiential Experience in the Museum. Available online: http://design-cu.jp/iasdr2013/papers/1597-1b.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Allen, J.; Harris, R.; McDonnell, I.; O’Toole, W. Festival and Special Event Management, 5th ed.; Wiley: Milton, Qld, Austrilia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, K. The Museum Refuses to Stand Still. Mus. Int. 1998, 50, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, N. Knowing the Public. A Review of Museum Marketing Literature and Research. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 1998, 17, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, R. Images of a Museum. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2001, 19, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendroff, A.L. Special Events: Proven Strategies for Nonprofit Fundraising; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Axelsen, M.; Arcodia, C.; Swan, T. New directions for art galleries and museums: The use of special events to attract audiences, a case study of the Asia Pacific Triennial. HTL Sci. 2006, 3, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Julia, H. Museums and touristic expectations. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirezli, O. Museum Marketing: Shift from Traditional to Experiential Marketing. Int. J. Manag. Cases 2011, 13, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilburn, M. Managing the Customer Experience: A Measurement-Based Approach; ASQ Quality Press: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Wolf, L. Museum visitor preferences and intentions in constructing aesthetic experience. Poetics 1996, 24, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. Learning from Museums: Visitor Experiences and the Making of Meaning; Rowman & Littlefield Publisher: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McManus, P. Memories as indicators of the impact of museum visits. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 1993, 12, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Page, S.J. Event Studies: Theory, Research and Policy for Planned Events, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. Museums and Their Visitors; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, K.B. Enhancing the attendee’s experience through creative design of the event environment: Applying Goffman’s dramaturgical perspective. J. Conv. & Event Tour. 2009, 10, 120–133. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, B.; Lune, H. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 8th ed.; Pearson: Harlow (Essex), UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Opdenakker, R. Advantages and disadvantages of four interview techniques in qualitative research. Forum Qual. Soz./Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2006, 7. Available online: https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/175/391 (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Marshall, M.N. Sampling for qualitative research. Fam. Pract. 1996, 13, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D. Qulitative Interview Design: A practical Guide for Novice Investigators. Qual. Rep. 2010, 15, 753–760. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.D.; Marsh, E.E. Content Analysis: A Flexible Methodology. Libr. Trends 2006, 55, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford university press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, S.E. The Museum and the public. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 1997, 16, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. Are art-museum visitors different from other people? The relationship between attendance and social and political attitudes in the United States. Poetics 1996, 24, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradburne, J. A New Strategic Approach to the Museum and its Relationship to Society. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2001, 19, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Perspectives |

|---|---|

| [44] | The institutions as a part of an urban tourist service |

| [42] | Leisure activity market |

| [36] | Informal learning and leisure experiences, educational leisure sites |

| [46] | Leisure context for majority of the audience |

| [6,45] | Sustainability for museum or Museum Lates across diverse audiences |

| [47,48] | Education and amusement |

| [15] | Education and entertainment |

| [1] | Sustainable management of museums |

| Institutions | The Museum Late | Event Date | Number of Interviewees | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visitors | Event Coordinators | |||

| NHM | Lates | 30 July 2016 | 18 | 2 |

| After-School Club for Grown-Ups and Silent School Disco | 22 July 2016 | |||

| Dino Snores for Grown-Ups | 5 August 2016 | |||

| Total: 20 | ||||

| Science Museum | Lates: Power Up | 27 July 2016 | 5 | 0 |

| Tate Modern | Tate Tap Takeover | 28 July 2016 | 5 | 0 |

| V&A Museum | Friday Late (October 2015) | 30 October 2015 | 1 | 0 |

| Friday Late (April 2016) | 29 April 2016 | 1 | ||

| Total | 28 | 2 | ||

| 30 | ||||

| Code | Organization | Position | Interview Style |

|---|---|---|---|

| EC-1 | NHM | Senior Event Coordinator | Semi-structured FGI |

| EC-1 | NHM | Senior Event Coordinator |

| Code | Nationality | Gender | Occupation | Age | Companion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-1 | Japanese | M | Student | 30s | Friends |

| R-2 | British | M | Working | 30s | Friends |

| R-3 | American | F | Student | 10s | Alone |

| R-4 | British | M | Working (entertainment industry) | 20s | Friends |

| R-5 | American | M | Working | 30s | Alone |

| R-6 | British | M | Working (art industry) | 30s | Co-workers |

| R-7 | Canadian | M | Working (art industry) | 30s | Co-workers |

| R-8 | British | F | Working (art industry) | 70s | Friend |

| R-9 | British | F | Working (art industry) | 60s | Friend |

| R-10 | British | F | Student | 20s | Friends |

| R-11 | Italian | F | Tourist | 30s | Partner |

| R-12 | Czech | M | Tourist | 10s | Mother |

| R-13 | Czech | F | Tourist | - | Son |

| R-14 | British | F | Working | 30s | Son and friends |

| R-15 | British | M | Working | 30s | Friends |

| R-16 | British | M | Working | 20s | Sister |

| R-17 | Korean | M | Tourist | 40s | Family |

| R-18 | British | M | Working | 20s | Friends |

| R-19 | Canadian | F | Tourist | 20s | Friends |

| R-20 | British | M | Working | 40s | Social club members |

| R-21 | Chinese | F | Student (event major) | 20s | Friends |

| R-22 | Thai | F | Student (event major) | 20s | Friends |

| R-23 | Taiwanese | M | Student | 20s | Friends |

| R-24 | British | F | Working | 40s | Partner |

| R-25 | Finn | F | Student | 20s | Alone |

| R-26 | British | F | Working | 50s | Friend |

| R-27 | British | F | Working | 40s | Friend |

| R-28 | Chinese | F | Student (event major) | 20s | Friends |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, A.; Berridge, G.; Kim, C. The Urban Museum as a Creative Tourism Attraction: London Museum Lates Visitor Motivation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229382

Choi A, Berridge G, Kim C. The Urban Museum as a Creative Tourism Attraction: London Museum Lates Visitor Motivation. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229382

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Ayeon, Graham Berridge, and Chulwon Kim. 2020. "The Urban Museum as a Creative Tourism Attraction: London Museum Lates Visitor Motivation" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229382

APA StyleChoi, A., Berridge, G., & Kim, C. (2020). The Urban Museum as a Creative Tourism Attraction: London Museum Lates Visitor Motivation. Sustainability, 12(22), 9382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229382