Abstract

Using the extended theory of planned behavior, this study examined individuals’ cognitive and psychological determinants of their intentions to donate to nonprofit organizations (NPOs) with either a positive or negative chief executive officer (CEO) reputation. With the use of online survey data (n = 371), the similarities and differences in the relationships between the determinants were analyzed for the two NPO CEO reputations. To verify the hypotheses, multiple regression was used to analyze the data. The results reveal that for NPOs with positive CEO reputations, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, moral norms, past behavior, and identification had positive effects on the intention to donate. In contrast, for NPOs with negative CEO reputations, subjective norms and identification had positive effects on the intention to donate. Attitude toward the NPO was not related to donation intentions regardless of the CEO’s reputation. These findings suggest the need for strategies to increase the public’s intentions to donate to problematic NPOs with negative reputations. Additionally, a strategy to further strengthen the intention to donate in the case of a positive CEO reputation is proposed. Theoretical and managerial implications of the results are also discussed, highlighting important considerations for CEO reputations and NPO management in the short and long terms.

1. Introduction

Donation is an action that must be sustained in order to practice love for humanity and to develop an inclusive society. The simple act of sharing a portion of personal property is a driving force that changes our global society. As countries around the world achieve economic growth and evolve from quantitative growth to the pursuit of improving the quality of life, donation has become a significant factor in the modern way of life [1]. Donations contribute to improving welfare around the world through effects such as improving economic inequality and class imbalance, children’s education, and living standards [2]. The role of nonprofit organizations (NPOs) is also gradually expanding, along with the increase in the need for their work. They play an important role in providing necessary services and materials to those in need at the local, national, and international levels [3]. Despite the significant efforts of NPOs, donations are on the decline worldwide.

According to the Charities Aid Foundation (CAF) data index of accumulated donations from 126 countries over the 10 years from 2009 to 2018, donations from superpower countries such as the United States (first), Canada (sixth), the United Kingdom (seventh), and the Netherlands (eighth) gradually decreased [4]. In addition, Poland and the Czech Republic were the countries with the largest declines in their average scores over the 10 years, and their monetary contributions decreased significantly [4]. In comparison with high-donation countries, Korea ranked 57th; compared with its rapid economic growth, ranking 11th–12th in GDP (gross domestic product) over the past five years, Korea’s donation culture remains at the level of developing countries. In particular, in a 2019 social survey by the Korea National Statistical Office, the number of respondents who reported having donation experience decreased steadily over 10 years: 36.4% in 2011, 34.6% in 2013, 29.9% in 2015, 26.7% in 2017, and 25.6% in 2019 [5].

It should be noted that trust in the nonprofit sector, in general, has been steadily declining, as have donations from Korea and other countries around the world. According to the Edelman Trust Barometer Global Report 2018 index of trust data from 28 countries, trust in the nonprofit sector decreased from 55% in 2016 to 53% in 2018 [6]. It is particularly noteworthy that in the United States, a donor powerhouse, trust decreased from 57% in 2016 to 49% in 2018 [6]. In addition, in the United Kingdom, respondents who indicated that they trusted charities decreased by 3%, from 51% in 2016 to 48% in 2018 [7], and in Korea, the percentage of respondents who indicated that they distrusted such organizations increased from 8.9% in 2017 to 14.9% in 2019 [5].

In many places, distrust is one of the direct results of corruption scandals among the chief executive officers (CEOs) of nonprofit organizations. For example, in the United States, between the years of 2008 and 2012, four organizations—the Cancer Fund of America, Cancer Support Services, Children’s Cancer Fund of America, and Breast Cancer Society—raised about US$187 million, but it was later revealed that all but 2.5% of the grand total of funds had been embezzled [8]. Most of the money was spent on the personal expenses of the founder, James Reynolds Sr., his family, and other staff members. The employees who were implicated in the embezzlement were charged. In 2018, Korea had its NPO CEO embezzlement scandal [9]. The New Hope Seed raised US$10.7 million, purportedly to support disadvantaged children and teenagers. However, the CEO used most of the money on apartments and overseas travel. Later, the CEO, who embezzled the children’s prospects as collateral, was sentenced to imprisonment. There are many similar negative reports about other nonprofit CEOs, and such problems have caused donors to be cautious about donating. Corrupt nonprofit CEOs worldwide have created a crisis for NPOs and the donation culture in general.

Therefore, this study examined the relations of NPO CEO reputations and individuals’ donation intentions. A CEO, or chief executive officer, provides strategic direction to organizations and has the ultimate responsibility for all company activities [10]. Beyond personal reputation, a CEO’s individual qualities and abilities are associated with a company’s reputation, including their effects on the company’s likability and economic benefits [11]. Reputation, as an intangible asset with a significant effect on real value investment, can play a role in for-profit companies’ abilities to secure resources and in nonprofits’ abilities to attract donors and funds. Understanding the perceived CEO reputation of the public will help in developing strategies to increase donation intention.

However, previous researchers have mainly studied the effect of an organization’s reputation, rather than the reputation of the CEO [12,13,14,15,16]. To our knowledge, research has not explored the socio-cognitive determinants of how the NPO CEO reputation influences donation intentions. In view of the issues and troubling number of donation scandals over the years, it is important to study the NPO CEO reputation in the context of donation. Accordingly, the current study is an attempt to address this problem and arrive at possible solutions.

Toward this goal, this study applies the theory of planned behavior to evaluate the effects of an individual’s cognitive and psychological factors on donation intention and derives a donation strategy for NPOs that aligns with the CEO’s reputation. This study verifies the influence of factors relating to donation intentions as established through prior research and examines how donation intentions may differ depending on a positive or negative CEO reputation. Therefore, the current study poses two research questions to examine how a positive or negative NPO CEO reputation activates the proposed cognitive and psychological factors in relation to an individual’s intention to donate. This study is expected to provide practical implications for developing strategies to increase donation intentions.

Research Question 1 (RQ1).

How does an NPO CEO’s positive reputation activate the proposed cognitive and psychological factors associated with individuals’ donation intentions?

Research Question 2 (RQ2).

How does an NPO CEO’s negative reputation activate proposed cognitive and psychological factors associated with individuals’ donation intentions?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Extended Theory of Planned Behavior (ETPB)

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) [17], expanded from Fishbein and Ajzen’s [18] theory of reasoned action, was designed to identify decisive factors in human social behavior. The TPB is used not only to predict certain behaviors but also to explore the intentions that lead to them [17]. The intention, influenced by attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control, leads to actual behaviors. In other words, the intention is a proximal determinant of behavior, and the more an individual wants to engage in a particular behavior, the more likely he or she is to do so [17]. Researchers have applied the TPB extensively across the wide range of academic fields to study individuals’ behaviors. Specifically, findings from the context of donation intentions and behaviors showed that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control had a large influence on such intentions.

First, attitude (AT) refers to the degree to which an individual evaluates a certain behavior favorably or unfavorably; a positive attitude promotes efforts to perform the behavior, while negative attitudes suppress the behavior [17]. Previous studies have shown considerable correlations between attitude and prosocial behavior. For instance, investigators found that attitudes toward blood donation [19,20], volunteer enrollment among college students [21], and organ donation [22] all affected individuals’ intentions to perform the studied behavior, and other researchers have confirmed that attitude is a major predictor of monetary donations [23,24].

Next, subjective norm (SN) refers to how important an individual considers a behavior based on perceived social pressure from referents whom the individual considers important. Individuals are more likely to perform behaviors if persons who are important to them have favorable reactions toward the behaviors and are less likely to perform them if important others hold negative reactions [17,25]. SN also has differing effects across different cultures, including noticeably different influences on donation intentions [26,27,28]. Researchers found that SN had no effect in individualist countries such as Canada and the United Kingdom [29,30] but a high effect in collectivist countries such as Pakistan and Malaysia [2,28,31]. These findings appear to reflect the differences between collectivist Eastern cultures that tend to be highly interdependent and Western cultures that value individuality [32].

Lastly, perceived behavioral control (PBC) refers to an individual’s evaluation of his or her abilities to perform a given behavior [17]. Individuals’ internal controls, such as self-confidence and ability, and external controls, such as money and time, facilitate their performance of certain behaviors [33]. In other words, individuals who determine that they have the required resources or capabilities to perform a certain behavior will perceive that they have high control over performing the behavior. Prior researchers have identified PBC as an influential factor in determining whether individuals donate money, blood, and organs, prosocial behaviors that reflect individual decision-making [2,34,35].

Many researchers are now leveraging behavioral intention and the predictive power of behavior components via an extended model that adds new external variables to the TPB. In donation studies, researchers have added various domain-specific variables to increase the TPB’s predictive power for donation intention and behavior. Researchers have consistently verified moral norms and past behavior as additional key factors that influence donation intentions.

Moral norm (MN) generally refers to an individual’s perception of whether a certain behavior is morally correct and his or her feeling of a personal responsibility or obligation to exhibit the behavior [36]. Warburton and Terry [37] suggested that moral norms were highly predictive of an individual’s altruistic behavior of donating blood. Smith and McSweeney [38] added moral norms to the TPB and found that MN had a more significant influence on an individual’s donation intentions and behaviors than other factors. Van der Linden [30] further confirmed the strong psychological influence of moral norms.

In addition, past behavior (PH), which many researchers insist should be considered in predicting the future [39], exerted a strong influence on the intention to donate. Kang et al. [40] studied the donation behavior of Korean donors. They revealed that the more donation experiences that the participant had, the higher the donation loyalty to a specific organization, thereby increasing actual donation intentions and behaviors. Feldman [41] demonstrated that children who have charitable sharing experiences in childhood are more likely to grow into generous and charitable adults. In other words, the experiential factor of an individual’s past donation behavior lowers the barriers to entry and contributes to making donations.

The literature review indicates that the extended TPB (ETPB) model has been employed as a useful tool for investigating an individual’s donation intention. Thus, this study attempts to analyze donor intentions by applying the following ETPB variables based on the findings of previous studies: attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, as well as moral norm and past behavior. We expect that these variables contribute to explaining an individual’s intention to donate based on a CEO’s positive or negative reputation. More specifically, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

It is expected that attitude toward an NPO would positively impact intention to donate.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

It is expected that subjective norms of an NPO would positively impact intention to donate.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

It is expected that perceived behavioral control of NPO donation would positively impact intention to donate.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

It is expected that an individual’s perceived moral norms would positively impact intention to donate.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

It is expected that the level of an individual’s past behavior would positively impact intention to donate.

Identification with the Nonprofit Organization (NPO) Chief Executive Officer (CEO)

During this study, in addition to engaging in cognitive evaluation, we speculated that study participants might assess the CEO’s reputation and develop psychological bonds. We also expected that psychological perceptions based on the CEO’s reputation would be closely related to the intention to donate. Therefore, to further explore the role of an NPO CEO’s reputation on public intentions to donate to the NPO, we added identification as an additional external variable.

Identification refers to the process of reconstructing one’s values, attitudes, and behaviors in the image of real or fictional characters that an individual strives to resemble [42] or the process of sharing inner experiences with others [43]. Findings from a study on content acceptance by media audiences indicated the involvement of a psychological mechanism by which study participants empathized with media characters and internalized the media content as though they themselves had been experiencing the events [44]. In fact, consumers often purchase products because they identify with the celebrities who promote advertising the products [45,46]. They wish to mimic the appearance, lifestyle, values, and habits of celebrities. Researchers have consistently confirmed the influence of viewers’ identification with celebrities on the effectiveness of celebrity advertising promotions.

Past literature also established that individuals may partially identify with the specific subject even if they do not agree with all values [47]. From the perspective of organizational identification, individuals identify with organizations based on values, differentiation, ethics, and recognition of legitimacy [48,49,50,51]. Identification will follow different patterns according to individual judgment criteria. From a business perspective, consumer identification with companies increases customer satisfaction and loyalty to these companies and reduces negative feedback [52]. It also promotes cooperative attitudes toward both work [53] and financial support [54].

Mael and Ashforth [54] explained that when individuals identify with a particular target, they perceive the target’s successes and failures to be their own, which can guide individuals’ behaviors to reflect those of the target. Identifying with influential individuals or organizations goes beyond a simple preference to direct actions. In this context, engaging the public’s identification with an NPO’s CEO has the potential to encourage donation intentions.

In summary, psychological interaction through identification produces more than a variety of positive effects on an individual. Identification with a specific subject affects not only the individual’s behavior but also the formation of values. This also affects the financial returns of companies and organizations. Accordingly, we predicted that study respondents would form meaningful identification with the CEO of nonprofits based on their value judgments of the reputation. Reputation and identification have a positive relationship and play a role in reinforcing emotional commitment [55]. Thus, individual-CEO identification is expected to affect donation intentions significantly and positively. This study aimed to analyze the influence of identification on donation intentions based on positive and negative CEO reputations. This discussion leads to the development of the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

It is expected that individual’s identification with an NPO’s CEO would positively impact intention to donate.

2.2. NPO CEO’s Reputation: Positive or Negative

Reputation is stakeholders’ accumulated beliefs or opinions about the characteristics and behavior of people or objects from the past to the present [56,57,58,59]. It is a consistent and overall assessment accumulated over time [60]. Fombrun et al. [61] explained that a good reputation serves as a magnet that attracts funds from sponsors. A favorable reputation is the driving force behind the creation of real value in the organization and may act as a buffer or shield in times of crisis [62,63]. It also enhances the value of organizations and individuals [64], and this improved value not only increases loyalty [65,66,67] but also plays a role in promoting positive feedback and product sales [68,69]. In contrast, a negative reputation decreases respect for a company’s advertising messaging [70] and the probability of purchase [71,72,73]. Consumers may also question the motives of the company’s CSR (corporate social responsibility) activities [74]. In other words, consumers’ evaluations of firms depend on how those consumers perceive a firm’s reputation [75].

One of the tactics that can improve reputational awareness from a business’s perspective is the management of the CEO’s reputation. Past research on reputation has focused on economics, organizational science, and marketing. However, as reputation research has matured, it has expanded to the study of the influences of personal reputations. Personal reputation acts like an individual’s credit report [11]. Thus, research is ongoing on the importance of the reputations of influential individuals including CEOs, presidents, politicians, entertainers, and sports stars.

CEO reputation has been predominantly studied in the field of personal reputation. Gaines-Ross [76] asserted that CEO reputation is a corporate asset formed by the CEO’s prestige and brand, as well as the overall respect held by internal and external stakeholders. The author emphasized that CEO reputation, like other assets, should be invested in and managed. To do that, the author suggested, the CEO’s competitiveness should be secured through trust, ethical principles, communication, and organizational and employee management. Burson-Marsteller [77], a public relations company, conducted a study in Belgium and found that companies with a high reputation generally had CEOs with high reputations. In short, how stakeholders rate a CEO’s reputation affects not only individuals but further organizations.

These effects of reputation can also be applied to donation research, a social domain. To our knowledge, there is no empirical documentation regarding an NPO CEO’s reputation coupled with the intention to donate. However, there are prior studies in which the influence of reputation has been applied to donation research. Holmes [78] studied students’ alma-mater sponsorship intentions after graduation. The study suggested that students who recognize their universities’ high public status are more likely to maintain a strong relationship with the university. Furthermore, researchers who examined the importance of an NPO’s reputation found that people were not reluctant to donate to reputable charities [15,79]. An NPO’s high reputation has been also found to positively impact people’s willingness to donate [15,80]. These studies prove that the concept of reputation is an important reference for measuring the public’s intention to donate.

Taken together, the present study was approached by the insights obtained from the research on the for-profit CEO reputation. This study assumes that public recognition that a nonprofit had a reputable CEO would positively affect the intention to donate by activating cognitive and psychological factors. In contrast, when the CEO of an NPO has a bad reputation, we speculate that the effect of cognitive and psychological factors on the intention to donate will be distinguishable from the result of a good reputation. Therefore, this study identifies the determinants that influence the intention to donate when the NPO CEO’s reputation is positive or negative and further examines the results’ differences.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Sampling Procedure and Sample

For this study, data agency Market Link administered the survey data collection. The study sample was chosen from South Korean residents; 400 respondents completed their survey questionnaire during the period of 31 July and 4 August 2020. The quota sampling method was employed to reflect a balance of both gender and age groups.

An online survey was employed, and two types of CEO scenarios were devised to portray CEO reputations (positive vs. negative). We assigned 200 participants to the positive scenario and the other 200 to the negative scenario, respectively. After exposure to each scenario, the respondents were asked to fill out their questionnaires. We excluded 29 surveys for unreliable or insincere responses, leaving a final data sample of 371 survey respondents (positive: n = 194; negative: n = 177). Thus, the yield rate calculated was 92.8%. The logic behind the classification of the two groups into positive and negative was driven by the work of Kim, Youn, and Lee [81], who classified the corporate CSR reputation into positive and negative record groups and analyzed consumer support for cause-related marketing. Based on their research, the groups in this study were separated based on their exposure to the NPO CEO’s positive or negative reputation.

In terms of their demographic characteristics, 186 (50.1%) of the survey respondents were male and 185 (49.9%) were female. Furthermore, 83 (22.4%) of the respondents were aged 50–59, followed by those aged 40–49 (76, 20.5%), 20–29 (73, 19.7%), 30–39 (72, 19.4%), and over 60 (67, 18.1%). The demographic profiles of respondents are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic profiles for the sample (N = 371). KRW: Korean Won.

3.2. Procedure

To test the hypotheses, using the reputation of the CEO of Giving Goods, a virtual nonprofit organization that raised charitable funds for social contribution, we created two scenarios: positive and negative. Giving Goods is an organization that has been manufactured for research and does not exist. Participants were asked to read the scenario, which explained the purpose of the NPO and its CEO’s reputation. We based our descriptions on Gaines-Ross’s [76] CEO reputation for both the positive and negative CEO reputations. Trust in the CEO, transparency, communication, organization, and crisis management elements were included.

To reduce the systematic bias caused by specific words in the CEO’s reputation, we constructed scenarios by using terms with opposite meanings. For example, we used positive and negative adjectives, such as high vs. low and active vs. passive, that indicate the opposite meaning. Moreover, we employed the words ‘no’ and ‘not’ to describe parts of the negative reputation scenario. Respondents were provided with a URL for completing the survey on their donation intentions after they read the scenario. The scenarios were written in Korean, but English translations of each scenario are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Two chief executive officer (CEO) reputation scenarios.

To assess the success of our constructed CEO reputations, the respondents were asked to rate their assigned scenario as more positive or more negative on a five-point Likert scale. A calculated t-test statistic indicated a significant difference between the two scenarios in the expected direction (t = 28.435, p < 0.001). That is, respondents who were exposed to the positive CEO record perceived the record to be positive (M = 4.010, SD = 0.675), while participants who were exposed to the negative record perceived the record to be negative (M = 1.932, SD = 0.728).

3.3. Measures

To measure the variables that are integral to this study, we employed the following definitions: (1) Attitude (AT) is a general evaluation of an NPO, assessed with three semantic differential scales; (2) subjective norm (SN) is the consideration of important people who might have influenced the respondents’ donation intentions; (3) perceived behavioral control (PBC) is the amount of control one has with regard to actual intention to donate; (4) moral norm (MN) is the perceived ethical responsibility toward NPOs; (5) past behavior (PH) is the experience of donating in the past and whether they have engaged regularly; (6) identification (ID) is whether respondents felt that the opinions and values of the NPO CEO were similar to their own or if they wanted to resemble the CEO; and (7) intention to donate is the willingness or plan to donate in the near future.

Measurement of the ETPB factors was devised with reference to the results of previously published studies. The works of Smith and McSweeney [38] and Mittelman and Rojas-Méndez [29] were mainly used, and the measurement of ID was guided by Hoffner and Buchanan [46]. We used a total of 23 questions to measure the study survey respondents’ intentions to donate to the Giving Goods, a virtual nonprofit organization. All items except for the scenario verification used a seven-point Likert scale that ranged from ‘definitely not’ to ‘definitely’ or ‘not at all’ to ‘frequently’; the questionnaire was written in Korean. Table 3 presents the detailed questions that we used to measure the study variables.

Table 3.

Measure of constructs.

To analyze the data, we first conducted an independent-sample t-test for each variable to analyze the differences between the two groups according to the positive or negative CEO reputation. Next, we performed multiple regression to analyze the magnitude and direction of the influence of each independent variable on the dependent variable, followed by the analysis of the relative magnitudes of the different independent variables’ influences. We analyzed all data using SPSS 18 statistical software.

4. Results

Prior to conducting the study, we performed a descriptive statistical analysis of the dependent and independent variables to characterize the data and interpret the data more easily. The Cronbach’s alphas for each variable showed high internal consistency in the range of 0.759–0.964. Table 4 presents details, including standard deviations (SD) and correlations among the predictor variables.

Table 4.

Correlation data among the constructs.

The independent-sample t-test on the survey results for positive and negative reputations revealed statistical differences in all variables. The analysis results are shown in Table 5. Overall, the findings show that the means for each variable in the positive reputation group were higher than those in the negative reputation group in the following order: ID (mean difference: 2.757), AT (mean difference: 2.568), SN (mean difference: 2.229), intention to donate (mean difference: 1.671), PBC (mean difference: 1.115), MN (mean difference: 0.767), PH (mean difference: 0.400).

Table 5.

Independent-samples t-test comparisons of positive versus negative reputation findings.

Furthermore, prior to multiple regression, we evaluated the potential problem of multi-collinearity. Our verification determined that the variance inflation factor (VIF) ranged from 1.150 to 6.465, and the tolerance ranged from 0.155 to 0.869. An examination of the collinearity statistics revealed that each predictor fell within acceptable boundaries of tolerance (>0.1) or VIF (<10), ruling out any substantive multi-collinearity threats [82].

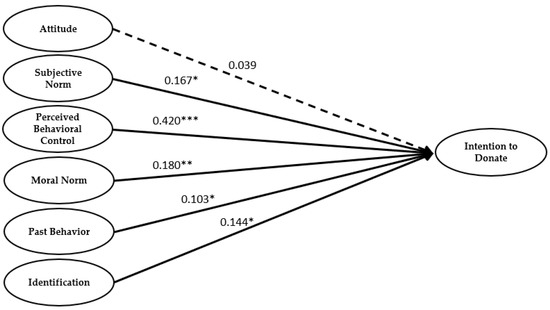

4.1. Positive CEO Reputation

Hypotheses 1–6 were based on the expectation that individuals’ intentions to donate to an NPO would be associated with the cognitive and psychological determinants of respondents’ perceptions of the nonprofit CEO’s reputation. In the regression model that measured the effects of the six independent study variables on donation intention in the positive CEO reputation group, the F value was 54.628 (p = 0.000). The regression model accounted for 63.7% of the total variation of the dependent variable of donation intention (Table 6). The results showed that most of the cognitive factors were significantly related to the CEO’s reputation. Independent variables that significantly affected the donation intentions were SN, β = 0.167 (p < 0.05); PBC, β = 0.420 (p < 0.001); MN, β = 0.180 (p < 0.01); and PH, β = 0.103 (p < 0.05). Contrary to our expectation, AT had a non-significant impact on individuals’ intentions to donate.

Table 6.

Multiple regression results.

H6 proposed that identification, a psychological factor between the individual and the CEO, would be significantly and positively predictive of the intention to donate. The results showed that the research hypothesis proposed was supported at the significance level of p < 0.05, with the value of β = 0.144. This finding confirmed the influence of an individual’s identification with the CEO through the CEO’s reputation. Figure 1 shows the results of the regression analysis associated with a positive CEO reputation.

Figure 1.

Results of the analysis for nonprofit organization (NPO) with a positive CEO record (note: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

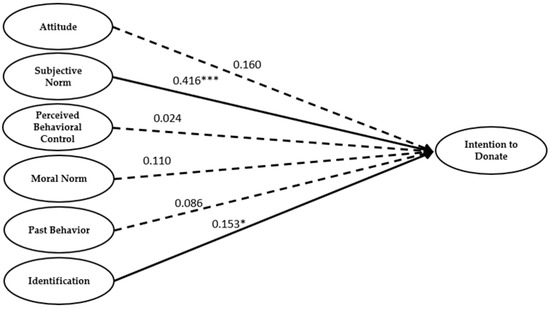

4.2. Negative CEO Reputation

The negative CEO reputation group, with all variables in the equation, accounted for 62.1% of the total variance in intentions (F = 46.463, p = 0.000). However, the pattern observed in the negative CEO reputation group differs from that in the positive group. In the negative reputation group, two predictors of SN (β = 0.416, p < 0.001) and ID (β = 0.153, p < 0.05) were found to significantly and positively impact intention to donate. In short, these findings indicate that SN and ID explain individual willingness to donate even if the CEO’s reputation is not favorable (see Table 6). However, the effects of AT, PBC, MN, and PH were found to be non-significant in predicting the intention to donate. Again, attitude emerged as a non-significant predictor of intention to donate in the negative CEO reputation group. Figure 2 illustrates the results of the regression analysis associated with a negative CEO reputation.

Figure 2.

Results of the analysis for an NPO with a negative CEO record (note: * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001).

5. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the cognitive and psychological determinants of donation intention in relation to the positive or negative reputation of a nonprofit organization’s CEO. Adding moral norms, past behavior, and identification to the existing TPB, we constructed an integrated model and empirically analyzed the statistical influences of each variable. Using the responses of a Korean sample to a constructed scenario, we assessed the individual effects of a set of independent variables to address two research questions exploring the influence of the positive or negative reputation of a nonprofit CEO on respondents’ intentions to donate to that NPO.

To address the research questions, it is important to discuss how the relationships between constructs are (or are not) different across NPOs. Regarding the similar pattern observed across the two groups of positive and negative CEO reputation (RQ1 and RQ2), subjective norms and identification showed significant associations with individual donation intentions, regardless of whether the CEO’s reputation was good or bad. These results indicate that when the NPO CEO’s reputation is good, this can be incorporated into strategies to strengthen donation intention. Leveraging subjective norms and identification to strengthen donation intention can be an effective promotional strategy for NPOs with a negative CEO reputation as well.

First, it was found that subjective norms (H2) significantly impacted donation intentions for both reputations. When determining behavioral values, the opinions of other influential people affect support for an action. Furthermore, when important others confirm the positive value of a donation, the donation intention is more likely to be highly formed. Prior studies have shown that SN has different degrees of influence in different cultures. High normative effects have been identified in Asian countries with highly interdependent collectivist cultures [2,28,31]. This study shows that SN has a high impact on both CEO reputations, which confirms that norms are also crucial for residents of Korea, an Asian country with a collectivist culture. These results support the results of prior studies conducted in collectivist cultural countries. Normative messages through important others should be delivered frequently. This is to emphasize not only that influential people consistently support one’s actions but also that their opinions help one’s decision. Further, seeing the donation process of influential celebrities can be effective for behavior modification. For example, if donation can be performed among celebrities in a reality TV program, this might motivate potential donors and raise awareness of donations.

It is noteworthy that identification (H6) influenced donation intention regardless of the CEO’s reputation. Nonprofit CEOs are not as well-known as for-profit CEOs. However, this study shows that the public can create an identification when a nonprofit CEO’s reputation is displayed, regardless of whether that reputation is positive or negative. We interpret this finding as identification formation by agreement to the value of the CEO. This type of value judgment and identification can directly affect donation intention: The stronger the identification with the NPO CEO, the greater the intention to donate. Therefore, it is necessary to provide information that can enhance the identification of NPO CEOs. In particular, emphasizing identification can lead to voluntary behaviors among citizens without special compensation for them [83,84,85,86]. Here, a person who has identified with a CEO could become a voluntary PR expert who actively informs others of relevant information. We arrive at this conclusion following prior evidence that identification with sports teams affects spectator consumption [87] and that identification with colleges significantly affects fundraising activity [54].

With regard to these findings related to identification, communicating with the public is the most important strategy. To promote good reputation, one communications strategy would be to share the NPO’s values, directions, and management plans that the CEO is considering. For instance, in addition to active communications online and offline, SNS (social networking service) viral marketing can be developed. This strategy would deliver shared values in a friendly and accessible way. A continuous exchange of shared values will help identification between the CEO and the individual and contribute to the development of donation intentions. In a bad reputation, a different communications strategy is needed. If there is a reputation-related problem, improvement must be directly delivered, and information that highlights the positive value of the CEO must be provided.

In contrast to our expectations, we found that attitude (H1) did not affect intention to donate in either reputation group. This finding contradicted prior findings that showed that attitude affected donation intention [19,23,88]. In other studies, however, cultural differences limited the influence of attitude [24,89], and variables such as moral norms and past behaviors had greater influence [90]. We propose two possible explanations for our findings. One, it may be that the perception of reputation did not play an important role in forming attitudes toward the organization or intention to donate because the scenario focused on the personal reputation of the CEO. If we manipulated the scenario for the NPO, the result for attitude might have been different. In addition, there is also the possibility that attitudes might not have had a significant effect because of the strong influence of subjective norms, a characteristic of Korea’s collectivist culture.

Next, we review the differences (RQ1 and RQ2) between positive and negative CEO reputations. In the positive reputation scenario, perceived behavioral control (H3), moral norms (H4), and past behavior (H5) were all significant, but they were all non-significant for the negative reputation. We interpreted this finding as indicating that perceptions of bad reputation have become an obstacle to activating the cognitive factor, which is an individual’s sense of control, belief, and moral responsibility. Additionally, respondents’ dissatisfaction with the bad reputation indicates that past behavior may not support future donation intention.

First, perceived behavioral control (H3) produced the greatest influence for the good CEO reputation group. This suggests that the stronger the belief in self-control and the more seriously one takes personal ownership of the donation decision, the greater the intention to donate. Indeed, the findings of this study are consistent with those of previous studies on blood and organ donation [34,35,91].

Moral norms (H4) had the second highest influence after PBC in the good reputation group; intention to donate increased with greater perceived moral responsibility. This result is consistent with previous findings for MN as a powerful predictor of actual donation behavior, along with moral responsibility or obligation [23,30,38]. Researchers consider the influence of moral norms to be a major factor in the TPB as well as in charitable donations in general [3,92,93].

Last, past behavior (H5) also showed significant results for the group with the good reputation scenario. Following Sargeant [94], who showed that satisfaction with past donation experiences affected donation behavior, we interpreted this finding to result from participant satisfaction with a good reputation. Accordingly, to increase the donation intentions of those with donation experience and to encourage them to become regular sponsors, satisfaction can be increased by continuing to maintain good reputation and delivering mementos or letters of appreciation. This is because psychological and social stimuli or external rewards from donations increase the willingness to donate to other donation agendas and strengthen the role that donors play [95].

Thus, PBC, MN, and PH were significant when the CEO’s reputation was good. It is essential to strategically emphasize that donations can begin changes in society, have a good influence on others’ lives, and be morally right. In the context of a negative CEO reputation, by contrast, it would be necessary to focus on solving fundamental problems, such as reputation, in a way that incorporates a long-term perspective and then using the communication strategies referred to above.

Donations are close interactions between donors and NPOs and are based on mutual trust that the money given will be used for its intended purpose. The CEO of a nonprofit organization is the person who oversees the organization’s management and is fully responsible for its transparency and trust. However, the scandals reported in the media regarding CEOs’ abuse of donations may cause the public to wonder if they should bother to donate or if their donations will be used appropriately. The strategies discussed above may have reinforced donation intentions while also helping organizations with negative reputations to overcome that challenge. However, these strategies can only be a short-term solution. To increase the sustainability of a donation culture, it is necessary to have a good reputation that can build trust over the long term.

Nonprofit CEOs should focus on reputation management. When incidents that negatively reflect on business ethics occur, people do not rely on traditional media coverage alone. Instead, they interpret news, evaluate companies, and share information with others. At present, positive effects must remain sustainable over the long term, in any field. Thus, it is necessary to increase CEO and NPO value through reputation management. This enhanced value benefits donors’ loyalty and plays a role in promoting positive feedback. When a good reputation is established, it is necessary to actively promote its content of a good reputation through a range of media channels. Communicating a good reputation can be useful information that potential donors can use to judge a nonprofit organization’s CEO and develop a donation intention. The work of Román-San-Miguel and Díaz-Cruzado [96] also highlights the need for expert communication with the public through media channels in the nonprofit sector. This communication can produce to a link between the organization and the audience [96]. Thus, it is time to suggest sufficient information so that donors can evaluate in multiple dimensions and select the NPOs they wish to donate to. If the communication strategy is pursued after reputation management begun, it will improve the overall donation culture. Managing reputation requires significant effort and time. However, these efforts are essential for the sustainability of the donation culture and the recovery of public trust in NPOs.

6. Conclusions and Limitations

This study investigated determinants that affect individuals’ intention to donate to an NPO when its CEO has either a positive or a negative reputation. We compared and discussed similarities and differences in relationships among the determinants and derived important implications from these discussions from a deeper perspective. It is noteworthy that, unlike the case of corporate CEOs, systematic research has not been conducted on the effects or relations of NPO CEOs on donation intention in past literature. In the past, individual donation decisions focused mostly on evaluations of NPOs, whereas in this study we emphasized the role of the reputation of the NPO CEO. Managing the CEO’s reputation will enhance the value of the NPO and the CEO, and it may help produce a donation culture that has a good influence on society. This study empirically identified methods of increasing donor intentions from the perspective of the CEO’s reputation. Although there are relatively modest contrasts across NPOs with good or bad CEO reputations, these findings provide practical information that the controversial NPO must alter the relevant reputational aspect to improve public donations.

Separately from these theoretical findings and managerial implications, this study had a few limitations. First, as there is not a well-known or validated scale that can be used to evaluate NPO CEOs, scenarios were constructed based on reputation factors in for-profit company CEOs. A non-profit organization CEO reputation scale could have produced more detailed research results. Therefore, in future study, an NPO CEO reputation scale should be created. Second, to obtain a better understanding of individual-CEO identification, a qualitative analysis of the reasons for the respondents’ decisions is needed. Knowing the cause of the identification will be essential in managing the reputation of the NPO CEO and establishing a better marketing strategy. Third, following previous research, this study examined both those with and without past donation behavior. It may be interesting to identify the antecedents to intention to re-donate or continuance intention to donate. Future studies may obtain more detailed results for groups with past donation behavior. Lastly, follow-up studies should utilize stratified sampling to identify the differences between groups more accurately.

Author Contributions

E.K.H. suggested the initial research idea; H.H.K. performed the literature review, designed the experiments, and analyzed the data; H.H.K. and E.K.H. both wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ein-Gar, D.; Levontin, L. Giving from a distance: Putting the charitable organization at the center of the donation appeal. J. Consum. Psychol. 2013, 23, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M.; De Run, E.C. Money donations intentions among Muslim donors: An extended theory of planned behavior model. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. 2015, 20, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.K.; Chan, C.M. Social-cognitive factors of donating money to charity, with special attention to an international relief organization. Eval. Program Plan. 2000, 23, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charities Aid Foundation; CAF World Giving Index. Available online: https://www.cafonline.org/about-us/publications/2019-publications (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Korea National Statistical Office. Available online: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/1/1/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=383171 (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Edelman Trust Barometer Global Report 2018. Available online: https://www.edelman.com/research/2018-edelman-trust-barometer (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Charities Aid Foundation; CAF UK Giving 2019. Available online: https://www.cafonline.org/about-us/publications/2019-publications/uk-giving-2019 (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- CNN. FTC: Scam cancer charities kept millions of dollars. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2016/04/01/health/cancer-charities-scam/index.html (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Yonhap News Agency. Transparency issues causing S. Koreans to shun donations. Available online: https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20181227001900320?section=search (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Waldman, D.A.; Yammarino, F.J. CEO charismatic leadership: Levels-of-management and levels-of-analysis effects. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 266–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E.; Kim, Y.; Moon, H. A Study on the Effect Model of the corporate Reputation and the CEO Reputation: With Focus on Samsung and SK. Korean J. Advert. 2005, 16, 125–144. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegelmilch, B.B. Targeting of Fund-raising Appeals—How to Identify Donors. Eur. J. Mark. 1988, 22, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D.J.; Green, C.L.; Brashear, T.G. Development and validation of scales to measure attitudes influencing monetary donations to charitable organizations. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.; Gabriel, H. Image and reputational characteristics of UK charitable organizations: An empirical study. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2003, 6, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, M.-M. The effects of charity reputation on charitable giving. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2009, 12, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, A.; Lee, S. Donor trust and relationship commitment in the UK charity sector: The impact on behavior. Volunt. Sect. Q. 2004, 33, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- France, J.L.; Kowalsky, J.M.; France, C.R.; McGlone, S.T.; Himawan, L.K.; Kessler, D.A.; Shaz, B.H. Development of common metrics for donation attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and intention for the blood donation context. Transfusion 2014, 54, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masser, B.M.; White, K.M.; Hyde, M.K.; Terry, D.J.; Robinson, N.G. Predicting blood donation intentions and behavior among Australian blood donors: Testing an extended theory of planned behavior model. Transfusion 2009, 49, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okun, M.A.; Sloane, E.S. Application of planned behavior theory to predicting volunteer enrollment by college students in a campus-based program. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2002, 30, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrhofer-Reinhartshuber, D.; Fitzgerald, A.; Benetka, G.; Fitzgerald, R. Effects of financial incentives on the intention to consent to organ donation: A questionnaire survey. Transplant. Proc. 2006, 38, 2756–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, S.R.; Hyde, M.K.; White, K.M. Predictors of young people’s charitable intentions to donate money: An extended theory of planned behavior perspective. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 2096–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez y Pérez, L.; Egea, P. About intentions to donate for sustainable rural development: An exploratory study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Jones, L.W.; Courneya, K.S. Extending the theory of planned behavior in the exercise domain: A comparison of social support and subjective norm. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 2002, 73, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Lee, D.W. A test of theory of planned behavior in Korea: Participation in alcohol-related social gatherings. Int. J. Psychol. 2009, 44, 418–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivis, A.; Sheeran, P. Descriptive norms as an additional predictor in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2003, 22, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 209–278. [Google Scholar]

- Mittelman, R.; Rojas-Méndez, J. Why Canadians give to charity: An extended theory of planned behaviour model. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2018, 15, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, S. Charitable intent: A moral or social construct? A revised theory of planned behavior model. Curr. Psychol. 2011, 30, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M.; Sarifuddin, S.; Hassan, A. Charity donation: Intentions and behaviour. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.Y.; Rhee, J.H. Who Clicks on Online Donation? Understanding the Characteristics of SNS Users during Participation in Online Campaigns. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. Decomposition and crossover effects in the theory of planned behavior: A study of consumer adoption intentions. Int. J. Mark. Res. 1995, 12, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purewal, S.; Van den Akker, O. British women’s attitudes towards oocyte donation: Ethnic differences and altruism. Patient. Esuc. Couns. 2006, 64, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manstead, A.S.R.; Terry, D.J.; Hogg, M.A. The Role of Moral Norm in the Attitude–Behavior Relation. In Attitudes, Behavior, and Social Context; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, J.; Terry, D.J. Volunteer decision making by older people: A test of a revised theory of planned behavior. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 22, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; McSweeney, A. Charitable giving: The effectiveness of a revised theory of planned behaviour model in predicting donating intentions and behaviour. J. Community Appl. Soc. 2007, 17, 363–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Norman, P.; Bell, R. The theory of planned behavior and healthy eating. Health Psychol. 2002, 21, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Kim, Y.; Cho, J. Citizens’ giving behavior patterns: Exploring loyal citizens in giving. Korean J. Soc. Welf. 2010, 28, 205–234. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, N.E. Time is money: Choosing between charitable activities. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy. 2010, 2, 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, B.P.; Brown, W.J. Media, celebrities, and social influence: Identification with Elvis Presley. Mass. Comm. Soc. 2002, 5, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, J. Compensatory media use: An exploration of two paradigms. Commun. Stud. 1996, 47, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass. Comm. Soc. 2001, 4, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffner, C.; Cantor, J. Factors affecting children’s enjoyment of a frightening film sequence. Commun. Monogr. 1991, 58, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffner, C.; Buchanan, M. Young adults’ wishful identification with television characters: The role of perceived similarity and character attributes. Media. Psychol. 2005, 7, 325–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, K.-H.; Lee, G.-H. The study of the effect of consumer-company identification on consumer’s evaluation of company products and behavioral responses. Korean. Mark. Rev. 2004, 19, 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Teresi, M.; Pietroni, D.D.; Barattucci, M.; Giannella, V.A.; Pagliaro, S. Ethical climate (s), organizational identification, and employees’ behavior. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelman, H.C. Compliance, identification, and internalization three processes of attitude change. J. Confl. Resolut. 1958, 2, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Chatman, J. Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer–company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, B. Calculations, values, and identities: The sources of collectivistic work motivation. Hum. Relat. 1990, 43, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Gilat, G.; Weisberg, J. Perceived external prestige, organizational identification and affective commitment: A stakeholder approach. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2006, 9, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.; Shanley, M. What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Acad. Manag. Ann. 1990, 33, 233–258. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.J. Reputation: Realizing Value from the Corporate Image; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; pp. 192–209. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, J. Managing Reputational Risk: Curbing Threats, Leveraging Opportunities; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2003; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, L.; Melewar, T. Corporate reputation and crisis management: The threat and manageability of anti-corporatism. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2005, 7, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.M. Corporate identity and the advent of corporate marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1998, 14, 963–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Van Riel, C.B.; Van Riel, C. Fame & Fortune: How Successful Companies Build Winning Reputations; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmeyer, J.M. Effects of Positive Reputation Systems. Soc. Sci. Res. 2000, 29, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rein, G.L. A reference model for designing effective reputation information systems. J. Inf. Sci. 2005, 31, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.D. Hypotheses on reputation: Alliance choices and the shadow of the past. Secur. Stud. 2003, 12, 40–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.; Bitting, E.; Ghorbani, A.A. Reputation formalization for an information–sharing multi–agent system. Comput. Intell. 2002, 18, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.W.; Dowling, G.R. Corporate reputation and sustained superior financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsuki, H.; Iwasa, Y. How should we define goodness?—Reputation dynamics in indirect reciprocity. J. Theor. Biol. 2004, 231, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Foxall, G.R.; Pallister, J. Beyond the intention–behaviour mythology: An integrated model of recycling. Mark. Theory. 2002, 2, 29–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, M.E.; Hartwick, J. The effects of advertiser reputation and extremity of advertising claim on advertising effectiveness. J. Cons. Res. 1990, 17, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.; Hitchon, J.C. Cause-related marketing ads in the light of negative news. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2002, 79, 905–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creyer, E.H. The influence of firm behavior on purchase intention: Do consumers really care about business ethics? J. Consum. Mark. 1997, 14, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J. The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. J. Cons. Aff. 2005, 39, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahilevitz, M. The effects of prior impressions of a firm’s ethics on the success of a cause-related marketing campaign: Do the good look better while the bad look worse? J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2003, 11, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Cameron, G.T. Conditioning effect of prior reputation on perception of corporate giving. Public Relat. Rev. 2006, 32, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines-Ross, L. CEO Capital: A Guide to Building CEO Reputation and Company Success; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Burson-Marsteller. (Burson-Marsteller, Brussels, Belgium). Research International: CEO Reputation Study. 2003. Available online: https://issuu.com/burson-marsteller-emea/docs/ceoreport (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Holmes, J. Prestige, charitable deductions and other determinants of alumni giving: Evidence from a highly selective liberal arts college. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2009, 28, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, A. Relationship fundraising: How to keep donors loyal. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2001, 12, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beldad, A.; Snip, B.; van Hoof, J. Generosity the second time around: Determinants of individuals’ repeat donation intention. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2014, 43, 144–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Youn, S.; Lee, D. The effect of corporate social responsibility reputation on consumer support for cause-related marketing. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2019, 30, 682–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, R.M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukerich, J.M.; Golden, B.R.; Shortell, S.M. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder: The impact of organizational identification, identity, and image on the cooperative behaviors of physicians. Adm. Sci. Q. 2002, 47, 507–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, R.; Shamir, B.; Chen, G. The two faces of transformational leadership: Empowerment and dependency. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, S.S.; Stamper, C.L. Perceived organizational membership: An aggregate framework representing the employee–organization relationship. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D. Work motivation and performance: A social identity perspective. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 49, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.M.; Beasley, F.; Gamble, T. Brand loyalty of NASCAR fans towards sponsors: The impact of fan identification. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2004, 6, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T. Consumer values, the theory of planned behaviour and online grocery shopping. Int. J. Consum. 2008, 32, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Green, R.T. Cross-cultural examination of the Fishbein behavioral intentions model. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1991, 22, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozionelos, G.; Bennett, P. The theory of planned behaviour as predictor of exercise: The moderating influence of beliefs and personality variables. J. Health Psychol. 1999, 4, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, M.; Cairns, E. Blood donation and Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour: An examination of perceived behavioural control. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 34, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterhof, L.; Heuvelman, A.; Peters, O. Donation to disaster relief campaigns: Underlying social cognitive factors exposed. Eval. Program Plan. 2009, 32, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radley, A.; Kennedy, M. Charitable giving by individuals: A study of attitudes and practice. Hum. Relat. 1995, 48, 685–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, A. Charitable giving: Towards a model of donor behaviour. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callero, P.L.; Howard, J.A.; Piliavin, J.A. Helping behavior as role behavior: Disclosing social structure and history in the analysis of prosocial action. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1987, 50, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-San-Miguel, A.; Díaz-Cruzado, J. Communication and advertising in NGDOs: Present and future. IROCAMM 2019, 2, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).