Abstract

Resilience captures firm capability to adjust to and recover from unexpected shocks in the environment. Being latent and path-dependent, the manifestation of organizational resilience is hard to be directly measured. This article assesses organizational resilience of firms in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic with pre-shock corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance as a predictor that positively influences the level of organizational resilience to the external shock caused by the pandemic. We develop three theoretical mechanisms based on stakeholder theory, resource-based theory, reputation perspective and means-end chain theory to explain how CSR fulfillment in the past could help firms maintain stability to adapt to and react flexibly to recover from the crisis. We examine the relationship in the context of the systemic shock caused by COVID-19, using a sample of 1597 listed firms in China during the time window from 20 January 2020 to 10 June 2020. We find that companies with higher CSR performance before the shock will experience fewer losses and will take a shorter time to recover from the attack.

1. Introduction

Since its outbreak in December 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic has hit the global economy with an unprecedented crisis with respect to its cause, scope and severity [1,2]. It has lasted for eight months, and the crisis is not slowing down on its affecting the lives of people and survival of organizations around the world [3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 pandemic as a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) on 30 January 2020 [4], taking into consideration the devastating threat it imposes on human health. By the middle of August 2020, the WHO reported 21,756,357 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 771,635 deaths in 213 countries and territories around the world. Given its threat to human health, followed by mandated social distancing, lockdowns and transportation restrictions, the pandemic has profoundly hit the global economy via its pressure on supply chains [5], labor force, operation and sales of products and services [6].

As the first country hit heavily by COVID-19 crisis, China had taken early measures, coping with the destructive consequences caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and recovering from the disaster [7]. It is reported that although the country’s GDP in the first quarter of 2020 fell by 6.8%, the GDP in the second quarter increased by 3.2% It shows that the economic growth rate has changed from negative to positive, implying that the overall economy has shown a rapid recovery (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2020). During disruptions such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the resilience of commercial organizations becomes a critical issue to investigate [8,9]. The systematic shock of the COVID-19 pandemic and the later recovery in China make the country an appropriate context for research on organizational resilience which is defined as a system’s latent ability to endure adversity as well as to recover after a shock [10]. To survive unexpected events, organizations need to develop a resilience capacity which enables them to (a) cope effectively with unexpected events (need to be tested in a post-shock environment where firms are recessing) and (b) bounce back from crises [11] (need to be tested in a post-shock environment where firms begin to recover). The former captures the stability dimension of resilience, which is an organization’s ability to resist adverse circumstances, indicating that systematic shocks have no severe consequences as they fall within the boundaries of a firm’s coping range. The latter embraces the level of flexibility—a firm’s capacity to restore an acceptable level of functioning or return to normal state [10,12,13].

Recent studies have put forward the idea that organizational strategies or processes are important for building resilience [14,15]. However, little is known about which elements contribute to an organization’s resilience and how these actually work in a particular natural setting. In the event of the COVID-19 outbreak and continuation, more insightful investigations on predictors of firm resilience which involve peculiar conditions of the pandemic are needed. Especially, the shadow of fear and insecurity that the virus cast over the globe have made it more salient than ever The interdependence between social, environment and economic wellbeing is calling for socially and environmentally responsible behaviors of the business sector which would eventually benefit the firms themselves. How such socially responsible practice would actually help firms sustain their resilience in an unprecedented crisis such as COVID-19 is still scarcely explored. To address this issue, this research seeks to explore corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the role as a predictor of organizational resilience in the COVID-19 crisis.

As defined by Aguinis and Glavas [16] CSR covers, “context-specific organizational actions and policies that take into account stakeholders’ expectations and the triple bottom line of economic, social, and environmental performance.” The definition emphasizes the consideration for a broader set of stakeholders than shareholders merely, and the inclusion of social and environmental causes in addition to the objective of profit maximization. Although it is criticized that research on CSR lacks a coherent theoretical foundation [17], most of the perspectives employed to investigate the effect of CSR on firm performance are consistent in that they hinge on the benefits generated from an enhanced stakeholder relationship. In this research, we are going to synthesize various theories whose principles relate the benefits of CSR to the role of the stakeholder relationship, and use such principles to assess the level to which social responsibility practice engagement could help firms through a crisis in the external environment [18,19,20]. To be specific, we base our analysis on the premise of stakeholder theory and resource-based view to explain that via actively engaging themselves in socially responsible behaviors and activities, firms could develop sustainable bonds with major stakeholders and such bonds could generate valuable and unique resources such as information, knowledge, collaboration, reputation, loyalty, etc., that are difficult to be copied by competitors. The resources are generated with trust, commitment and stakeholders’ willingness to share burden and support the firm even in the difficult time [21]. Combined with the framework of organizational resilience which consists of stability and flexibility dimensions [10], we propose that CSR can contribute to firm capabilities of resisting the crisis (retaining stability) and re-bouncing back to the normal state (fostering flexibility). During uncertain conditions and severe turbulence, these advantages would be essential for firms to cope with exogenous shocks and bounce back from unexpected crises.

The present article is expected to contribute to the extant literature in several aspects. Our first intended contribution is to enrich resilience research by using a two-dimension concept which embraces the notion of resilience in a more comprehensive way. Previous studies use a one-dimension concept, namely reliability or adaptability to represent resilience, which can be partial and biased from both theoretical and empirical perspectives [22,23,24,25]. We employ stability and flexibility as the two dimensions of organizational resilience [26,27] considering that the mutual verification of the two dimensions will construct a more reliable framework and reduce the probability of errors. Moreover, COVID-19, given its unprecedented widespread scope and devastating severity, provides a unique natural setting for examining the resilience shown by firms. Worldwide systematic shocks are rare, which is why we seize the hit by the COVID-19 crisis to update the resilience measurement and findings. The findings obtained by this research would provide evidence on CSR in turbulence, thereby suggest theoretical as well as practical guides out of the crisis time.

Second, we develop a solid theoretical foundation for the relationships between CSR and both dimensions of organizational resilience by employing various strategy theories. We integrate stakeholder theory and resource-based theory to highlight the significant role of stakeholder engagement which is fostered via active CSR participation in both stability and flexibility dimensions of resilience. We count on the stakeholder approach of CSR to explain that CSR participation entails the considerate care for critical groups of stakeholders, which in turn fosters strong and enduring bonds between a firm and its stakeholders, then offer the firm strong support, both tangible and intangible, from its critical stakeholders. Meanwhile, resource-based theory suggests that such valuable and unique resources (i.e., bonding with stakeholders and support from them) are a source of competitive advantages which help firms to survive competitions and overcome difficult time. Therefore, good CSR performance could positively influence a firm’s in both stability and flexibility dimensions because it fosters strong and enduring bonds between a company and its stakeholders. Considering the special context of COVID-19, we conceptualize and employ the most updated data on the COVID-19 crisis in Chinese firms to empirically prove that the authentic stakeholder-company bonding resulted from the active participation in CSR will ignite its helpfulness in crisis time and contribute to both dimensions of organizational resilience, which is a key capability that helps firms out of the crisis [28,29].

2. Theory and Hypothesis

The topic of corporate social responsibility (CSR) has received a great deal of attention and has been the center of numerous discussions in both academic and practical contexts over the past three decades. Previous studies, including meta-analyses on CSR have proposed various theoretical perspectives to explain the mechanisms that CSR engagement could benefit different aspects of firm-level performance (e.g., [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]). As one of the earliest, the most popular and the dominant paradigms to be employed in investigating CSR-related issues, stakeholder theory suggests that CSR activities take into consideration the interest of different stakeholder groups in addition to shareholders, which would significantly benefit firms in a reciprocal and multilateral process [38,39,40,41,42]. The groups of stakeholders embraced by the notion of “society” in “corporate social responsibility” involve employees, suppliers, customers, environment and community, whose well-being and satisfaction substantially determine the success of the business. Socially responsible initiatives, which help a firm build up and maintain good relationships with critical stakeholders and receive support from them, therefore, are important for a business’s sustainable development. Since it was first suggested by Freeman (1984), the stakeholder theory has offered a new approach to think about responsibilities of a business as well as the benefits obtained via fulfilling such responsibilities.

What types of benefits could be obtained and how worthy they are to pursue could be explained by the notion of a resource-based view which emphasizes the possession of certain resources as a firm’s competitive advantages over its rivals (e.g., [43,44,45]). The enhanced stakeholder relationship developed by actively engaging in social activities and via ethically committing to socially responsible behaviors would be sources of unique and valuable assets such as information, knowledge, know-hows, expertise exchange and collaborations, reputation, etc. The uniqueness and valuableness of these resources lie in that they are imperfectly imitable. For example, information and knowledge are accumulated through different forms of CSR activities across time, and the raw resources obtained would go through the exploitation and transformation by the firm to become customized for their own. Reputation is also a type of exclusive resource obtained by CSR engagement. Good CSR performance will signal a positive reputation of being responsible and committed upon which stakeholders may rely to make assessments and decisions particularly in case of inadequate information.

Organizational resilience is defined as, “both the ability of a system to persist despite disruptions and the ability to regenerate and maintain existing organization” [10]. The concept of resilience has been discussed in the literature of organizational studies as a necessary capability to cope with external shocks such as natural disasters, economic recession and widespread epidemic [25,46,47,48,49]. Such external disturbances bring along with them a series of consequences to the economy including sharp declines in customer demand, disruption of supply chain, restriction or even suspension of operations. The exposure to such chaotic business environments requires firms to foster the ability to adapt, to innovate and be flexible in order to resist the crisis as well as to bounce back to the normal state as soon as possible, which is embraced in the notion of resilience. A resilient firm would be better prepared for coping with unexpected circumstances and thus suffer from less severe damage, and they are likely to recover quicker from the loss [50,51]. In this study, we follow the method by DesJardine, Bansal and Yang [26] to capture the manifestation of organizational resilience in two dimensions—(1) stability dimension which indicates the severity of loss, and (2) flexibility dimension which capture the time to recovery.

Based on above-mentioned theoretical perspectives, we propose that firms with a better CSR profile will perform better during such unexpected shocks such as COVID-19 compared to those with not so good a CSR profile. To be specific, we seek to discuss the effect of CSR performance before a crisis on organizational resilience during the crisis. When the firm encounters an unexpected turbulence in the environment, the support coming from major stakeholders such as employees, suppliers, customers and the government offers critical resources for the firm to adapt to and quickly overcome the crisis. We propose three mechanisms via which a pre-shock CSR performance could matter to the degree of resilience against the shock.

Firstly, CSR fosters stakeholder cooperation and reciprocation. By actively engaging in CSR from earlier, a firm has built around them a network of loyal and reliable partners, and, particularly, the bonding is developed on trust and commitment which would become essentially helpful when an environmental disturbance occurs. Firms run into successive difficulties which may lead to, for instance, a downturn in performance, but loyal suppliers, customers and employees who have been attached to the firm in a sustainable connection will stay. They would be more likely to tolerate mistakes rather than suspending the collaboration (in case of suppliers), leaving for other products or services (in case of customers) or changing the job (in case of employees). Relationships developed via CSR are sustainable and lasting ones [52,53,54]. The more firms engage themselves in socially responsible initiatives, the more authentic and enduring connections they can build around their critical stakeholders. These connections enable firms to stay updated with the changes in the market, which speeds up their adaption to new conditions [55,56]. This advantage becomes even more meaningful in the crisis context when everything is unprecedented, uncertain and unpredictable.

Second, CSR performance may enhance a firm’s reputation. The history of a company’s performance is a major reference for new partners to base on in the context of incomplete information [57]. For example, a good CSR profile may signal to investors and bankers about the firm’s legitimacy, reliability and corporate citizenship. The good reputation, therefore, could promote the access to financial capital, which is crucial to survive a crisis. New customers may choose a certain product or service over other similar ones based on their impression of the company’s reputation of being ethical and socially responsible. Given that the aggregate customer demand sharply declines in the crisis, any factor that could help attract new customers would be extremely valuable [58,59]. The history of active CSR participation could also differentiate the firm from other employers in the labor market to attract talents [60,61]. During the difficult time, the budget for all types of resources both financial and non-financial is narrowed down. The ability to recruit and keep the right people for the job would save significant time and other costs.

Third, CSR could foster the firm’s innovation capacity to gain competitive advantage to survive and even flourish at the middle of the crisis. The inputs for innovation may come from external forces such as resources and collaborations obtained from enhanced stakeholder relationships, or internal gains from fostered employee engagement and creativity [62,63,64,65]. As discussed above, good connections with an external stakeholder network provide firms with information, knowledge and ideas, which are valuable inputs for R&D activities and innovation outputs. Moreover, the spread of socially responsible culture which is coherent throughout the organization could foster the accumulation of the collective efforts of internal forces, increase employee morale and involvement in organizational learning, in generating ideas and making innovative decisions [28,66]. On the basis of these premises, the following two hypotheses are proposed.

- Stability dimension of resilience. Stability refers to the firm’s capacity to maintain their core operation and identity in the context of the changing environment [25]. In this study, the level of stability is manifested in the degree of loss resulted from the pandemic. More severe loss indicates a lower level of stability that the firm could maintain during the crisis. We predict that firms who perform better at CSR before the shock will suffer from a smaller magnitude of loss. Via the process of actively engaging themselves in social practices, firms have accumulated thorough and diverse understanding about the changing environment which facilitate them to absorb the change and quickly adapt to the new context [67]. The interactive and interdependent bonding with various groups in the operation, which foster sharing and supporting one another within the network, would in turn generate collective strength for firms to maintain stability and minimize the severity of loss [68]. Moreover, the engagement in CSR enables firms to stay updated to the signal of the change in the environment; thereby they could quickly identify, process and respond to threats [47]. The early identification and quick response allows firms to avoid the escalation of the problem and reduce the damage [69].

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The firm that has better CSR performance prior to the shock would be more likely to maintain the stability following the shock.

- Flexibility dimension of resilience. The level of flexibility indicates how much time it takes for the system to recover to the normal state [26]. We predict that CSR performance is positively related to the extent to which the firm reacts flexibly to the environmental turbulence by fostering collective points of view to generate innovative solutions, renovate the system and make timely decisions on the changing context. Firms with high CSR engagement would be more likely to foster stakeholder involvement in solving problems because they trust each other and have developed good collaboration from earlier activities. The close relationship with stakeholders could offer firms with diverse points of view and multidimensional sources of information accumulated from employees and broader stakeholder networks including indigenous groups, customers and outside and inside directors [26], which would in turn stimulate creativity and develop novel solutions to adapt to the unexpected shock. New strategies always entail a certain level of risk and uncertainty. The support of stakeholders who are directly affected by the application of those ideas will help to reduce the risk and shorten the testing time. This advantage in turn contributes to speeding up firms’ moving forward and recovering from the disruption. Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The firm that has better CSR performance prior to the shock would be likely to recover more quickly from the shock.

3. Sample and Method

We constructed a data set of 1604 companies publicly listed in China from the Shenzhen Stock Exchange and Shanghai Stock Exchange as the research sample. B-share firms are excluded because they disclose only financial data in their annual reports while other data needed for this study are unavailable. We also excluded firms in the financial sector because they follow different accounting standards. Given that the COVID-19 pandemic was broadcasted officially for the first time in CCTV news in China on the evening of 20 January 2020 (the daily stock trading in China closes at 3 p.m.), we identify 21 January 2020 as the shock starting day in our research. Companies regardless of industries are included given that the pandemic casts a threat over all the aspects of the economy.

Our dataset was compiled from two major sources including the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) and the Hexun (HX) CSR database. Data on firm-level accounting fundamentals and stock price were obtained from the CSMAR database. Data on CSR scores came from Hexun (HX) listed company’s social responsibility report which is the first vertical financial portal website in China. The database provides financial information services as well as annual ratings for CSR strengths and concerns under several categories [70,71,72].

In order to test our hypotheses, we conducted Study 1 and Study 2 which involves testing the effect of a firm’s pre-shock CSR performance on the magnitude of the drop in its stock price following the shock (representing the degree of stability) and on the time needed to recover from the drop to the pre-shock level (representing the degree of flexibility), respectively. In Study 1, we performed a series of OLS (ordinary least squares) models with robust standard errors in which the drop in stock price is regressed on a set of control variables and pre-shock CSR score. In Study 2, Cox proportional hazard models are employed in a survival analysis to capture the effect of CSR performance on the probability of the recovery and on the duration needed for the firm to recover. One of the advantages of survival analysis is that it enables the consideration of a right censoring issue which occurs when the event of interest (i.e., the point of time when the stock price recovers to the pre-shock level) has not occurred by the end of the observation period. Specifically, in our sample, there are 300 firms in our original data out of 1604 observations falling on the right censoring problem. Taking this concern into account can increase internal validity and minimize biases estimates.

Details on variable measures and analysis procedures are presented in the following part.

4. Study 1

- Dependent variable

We follow Buyl, Boone and Wade [27] and DesJardine, Bansal and Yang [26] to measure a drop in a firm’s stock price following the shock as the first dimension of resilience—stability. It is captured by the absolute percentage change in closing price before (i.e., the closing price on January 20) and after the starting day of the COVID-19 on 21 January 2020 (i.e., the lowest closing price during the period from 21 January to 10 June). The higher this indicator is, the larger stock price drop it represents, which implies a lower degree of stability that the firm can maintain during the pandemic.

- Independent variable.

Corporate social responsibility refers to the company’s commitment to complying with ethical standards, contributing to economic development, improving the life quality of employees and their families and caring for the local community as a whole (World Commission on Sustainable Development, 1998). This article uses Hexun listed company’s corporate social responsibility report data as the measure for the level of CSR. The database includes five dimensions of social responsibility that firms take into consideration while operating their business: shareholder responsibility, employee responsibility, supplier, customer and consumer rights responsibility, environmental responsibility and social responsibility. Each of the five level-1 sub-indicators is constructed by further level-2 and level-3 sub-indicators.

Details of Hexun CSR index construction are illustrated in Table 1 [70]. These dimensions capture the firm’s level of responsibility fulfillment for five major groups of stakeholders. This measure, therefore, is in line with the stakeholder theory that we employ to consider CSR engagement in this research. The aggregate CSR score used in the models is the sum of these five dimensions and we take the average of the 2018 and 2019 as the representative score for a firm’s level of CSR performance prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1.

Hexun (HX) index system.

- Control variables.

We incorporated the following ten control variables into our study: firm size, age, R&D intensity, board independence, intangible assets, operating efficiency, financial leverage, ownership structure, GDP growth rate and industry dummies. Except GDP growth rate and industry dummies, all of the control variables are averages of 2018 and 2019. Size is the natural logarithm of the book value of total assets. Previous studies suggest that larger firms are more resilient than smaller ones. Age is calculated as the number of years from the firm establishment to 2019. Older firms can be more experienced to manage abrupt events. R&D intensity is calculated as the percentage of R&D personnel to total personnel, which reflects a firm’s efforts to build its long-run innovative capabilities. We assumed that R&D investment, as a long-term oriented and aspirational risk-taking activity, may cause a loss in stock price in short-run. Board independence is measured as the percentage of independent directors on the board; Board independence is shown by previous research to influence the process of decision making in the organization, which would significantly matter in the event of an external turbulence. Intangible asset is the natural logarithm of the book value of intangible assets, which usually include patent and trademark rights. It can typically represent the recognition of consumers, especially during a crisis. Operating efficiency is calculated as sales divided by the book value of total assets. Stakeholders during a crisis tend to stay with or turn to more efficient firms, preventing such firms from negative influence caused by the external shock. Financial leverage is the sum of long-term debt divided by the book value of total assets. Lower leverage indicates less financial risk. Investors and other stakeholders tend to become more sensitive to risk during an economic crisis, which in turn influences the firm’s resilience. Ownership structure represents the equity nature of a firm [73,74]. To be specific, a dummy indicator which is equal to 1 if the firm is state-owned and 0 otherwise. We included provincial GDP growth rate in the second quarter in order to capture the macroeconomic effects. Previous studies believe firm-level factors have direct effect on organizational resilience while overlooking macroeconomic and environmental factors. As mentioned before, Chinese economy has been hit by the COVID-19 pandemic and started to recover, this study additionally controlled macroeconomic effects to focus better on organizational resilience. We also create industry dummies to control for various sector-related differences.

- Regression results.

We select OLS models with robust standard errors to perform a regression analysis. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations for all variables. The findings in Spearman’s rank correlation matrix show that CSR is significantly and negatively associated with the severity of loss. Except for the correlation coefficient between size and intangible assets, all significant correlation coefficients between explanatory variables are less than 0.6, which indicates a low degree of multi-collinearity. Further, among all predictors, the variance inflation factors (VIFs) ranged from 1.01 for Board independence to 2.72 for Size. Given that the VIFs were less than 10, substantial multicollinearity was not present [75].

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations.

Results of the regression analysis are shown in Table 3. We entered all control variables in Model 1 and added CSR in Model 2. Hypothesis 1 predicts the positive relationship between pre-shock CSR engagement and organizational resilience. In support of hypothesis 1, the coefficient of CSR is negative and statistically significant (b= −0.002, p < 0.000), which indicates that a higher level of CSR is related to a lower level of decline in stock price.

Table 3.

OLS (ordinary least squares) regression estimates of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on drops in closing price.

5. Study 2

- Dependent variable.

The second study investigates the effect of prior CSR performance on the probability of a firm’s stock price recovering from the shock to pre-shock performance level. Since 21 January 2020 has been regarded as the starting day of COVID-19 crisis, we take the closing price on 20 January 2020 as the pre-shock performance level. Then we calculate the number of days (recorded as t) needed for a firm to recover its stock price to the level of pre-shock performance to obtain the duration of recovery used for duration analysis. The observation period spanned from 21 January through 10 June. The firms whose stock price did not recover to the pre-shock level at the end of the observation time window are treated as right censored. When the time duration is entered as the input, the results obtained by the Cox proportional hazard models model would tell us the probability that a firm would achieve the recovery level, given that the recovery has not been achieved up to a given point t during the observation period.

- Independent variable.

The same measurement of corporate social responsibility as the previous study is employed in this study.

- Control variables.

We used the same set of control variables as in Study 1.

- Estimation.

Cox proportional hazard models [76,77] are employed to estimate the effect of CSR on shortening firms’ recovery duration from the shock. At the end of the observation period, there are firms that have not recovered to their pre-shock levels. The recovery time of these companies is in (142, +∞) range. We use a right censoring approach to address this problem. Robust variance estimators are applied to calculate standard errors.

- Results.

The results of study 2 are presented in Table 4. In support of hypothesis 2, the coefficient representing the causal effect of CSR on the recovery probability is positive and statistically significant (b = 0.009, p < 0.05), which indicates that firms with higher levels of CSR are likely to have higher probability of recovery after the shock. Cox proportional hazard models also return a hazard ratio which facilitates the interpretation of the result. The ratio of CSR on the recovery of time which is equal to 1.009 (p < 0.05), indicates that for every additional point in a firm’s CSR performance, the probability of recovery increases by 0.9%.

Table 4.

Cox Survival Models for Recovery.

Given that all variables need to satisfy the assumption of proportional risk in order for the cox proportional hazard model to be applied, we conducted two tests to validate the proportional risk assumption. First, we perform a proportional risk test based on Schoenfeld residuals. If the hypothesis of proportional hazards is valid, the Schoenfeld residuals should not show regular changes over time. Thus, we regress the Schoenfeld residual to time, and then check whether the coefficient of time is equal to 0. According to the results, we can accept the assumption of proportionate risk from the perspective of the whole model and most variables. However, the variable size (p = 0.026) and ownership structure (p = 0.185) may violate the proportional risk assumption, which needs further verification. Second, we further introduce the interaction of time and size into the cox regression. As shown in Model 3, Table 4, the interaction term is not significant, suggesting that the variable size satisfies the proportional risk assumption. Similarly, in Model 4, the interaction of time and ownership type in the cox regression is not significant, supporting that the variable ownership structure satisfies the proportional risk assumption.

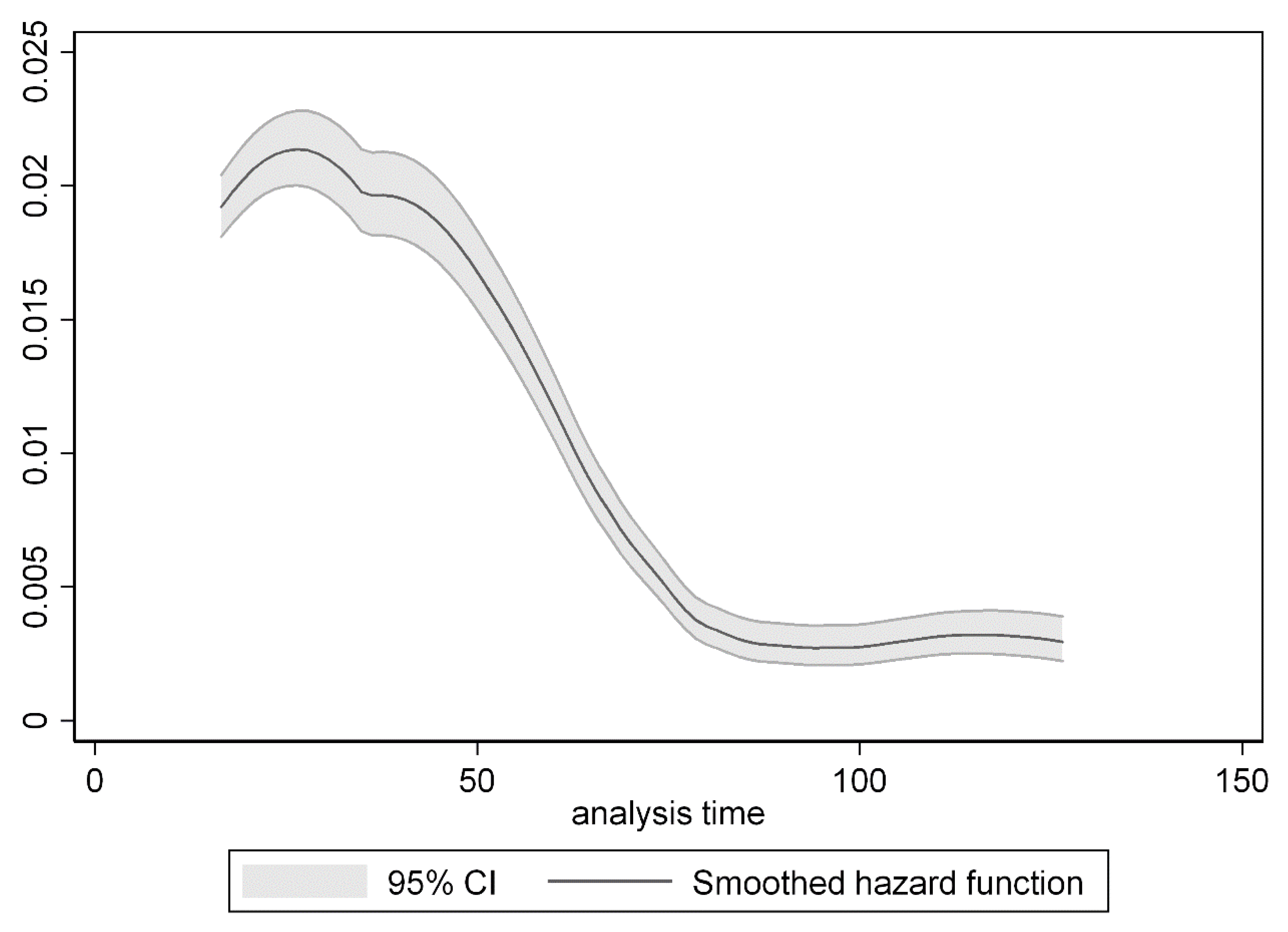

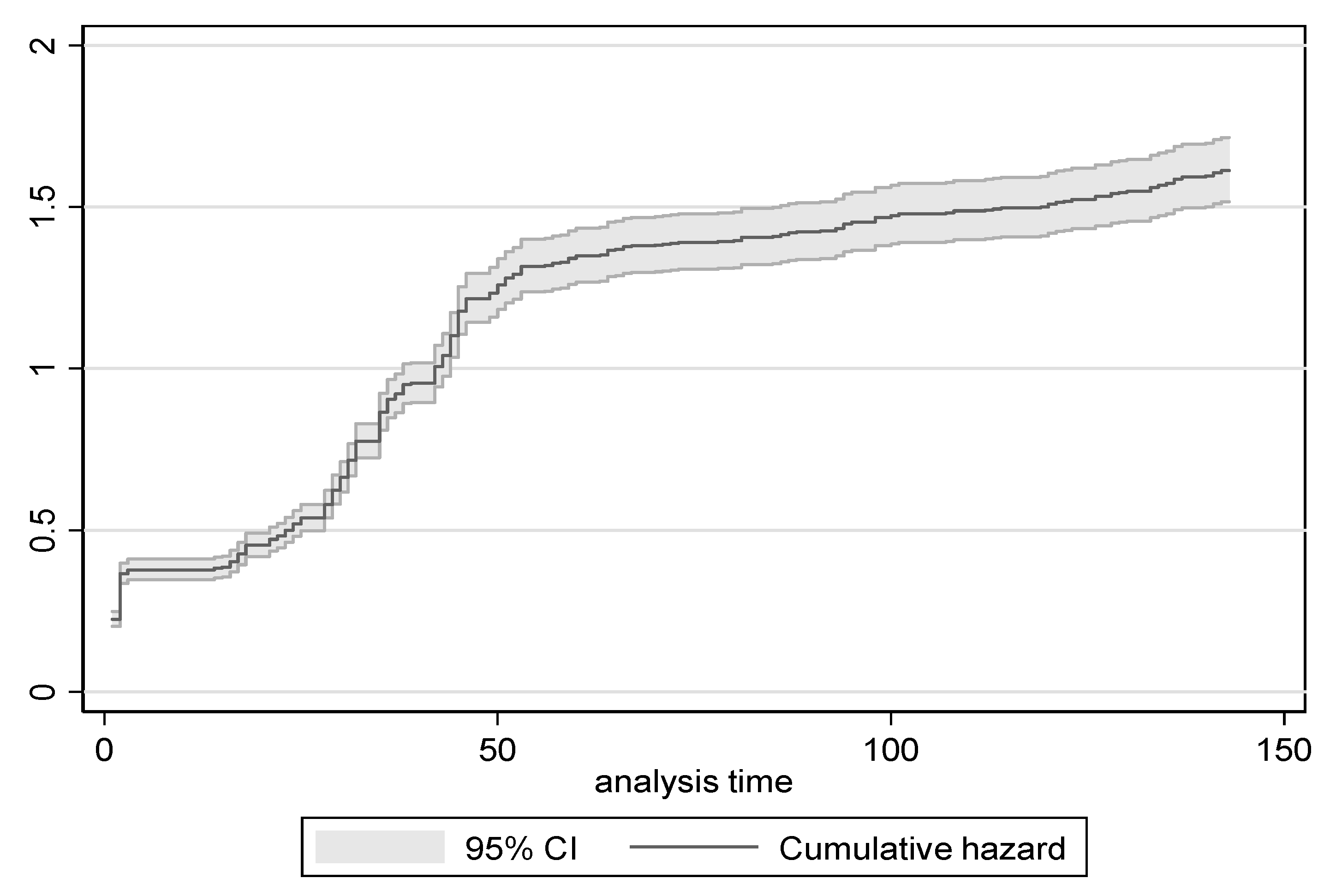

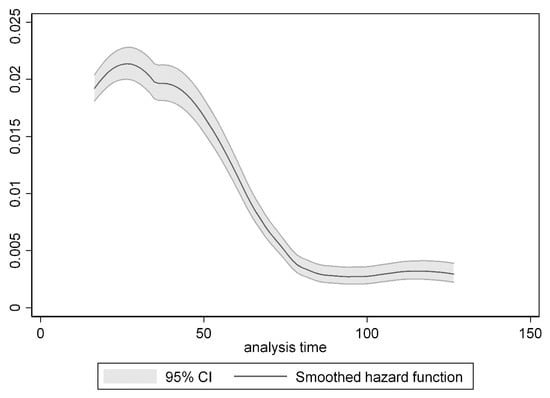

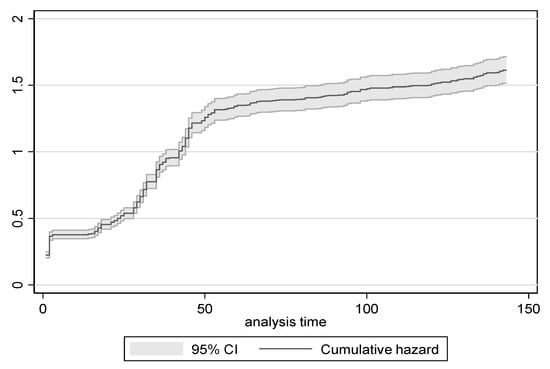

In addition, there exists a certain level of heterogeneity between state-owned and other ownership types (private companies, mixed ownership enterprise and so on), which may influence the regression results. It is assumed that individuals within a group are homogenous while individuals in different groups have heterogeneity, which is called “Shared Frailty”. We performed the test for shared frailty in Model 5, and the frailty was assumed to be subject to gamma distribution. The likelihood-ratio char2(01) is 0.000 and is not significant, suggesting that there is no shared frailty in ownership structure. As it can be seen from Figure 1, the hazard function shows that the probability of firm recovery is decreasing over time. Figure 2 illustrates the cumulative hazard function, which is the sum of hazard rate. The slope of this curve is decreasing over time, implying that the possibility of recovery becomes less with time going by.

Figure 1.

Smoothed hazard estimate.

Figure 2.

Nelson–Aalen cumulative hazard estimate.

- Robustness Tests.

In the proportional hazard model, we can use the maximum likelihood estimation to have a consistent and valid estimation, only if the distribution of the baseline hazard function is known. As is shown in Model 6 of Table 5, we assumed that the baseline hazard function follows an exponential distribution; here, the results remain unchanged. In Model 7, we assumed that the baseline hazard function follows Weibull distribution. In Model 8, we assumed that the baseline hazard function follows Gompertz distribution. Again, the results from these analyses are highly consistent with our main results.

Table 5.

Robustness.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Getting far beyond its threat to human health, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has been seriously affecting the global economy and every individual business worldwide. Just like everyone of us building up a strong immune system to deal with the disease, firms have to develop a high level of resilience when encountering such a sudden, unprecedented and severe external threat. No longer in panic, grief or questioning, firms are struggling for survival by minimizing the loss and shortening the time for getting back to normal state. Since the outbreak and spread of the pandemic, despite difficulties and restrictions in many aspects of research conditions, a lot of studies have been conducted, seeking for factors that could help to raise the degree of resilience of firm health. For instance, Golan, Laura and Igor [5] review the literature of global supply chain resilience to reveal the requirement for the network analysis and advanced resilience analytics, thereby finding out the absence of the framing of specific disruption scenarios used to develop and test supply chain resilience models as well as the utilization of more advanced models that merely focus on supply chain networks. Ding, et al. [78], one of the first research conducted on the influence of pre-2020 characteristics over firm resilience in COVID-19 provides empirical evidence that firms with stronger finance capacity, less exposure to global supply chain, and more CSR activities tend to suffer less severely from stock price drops. Rui, et al. [79] focus on environmental (E) and social (S) aspects to investigate the extent to which a firm’s ES performance could help to decrease the volatility of stock returns during the crash.

Our research on the one hand provides consistent results with previous studies in that we acknowledge the level of CSR engagement positively contributes to organizational resilience, which is the ability of firms to sense maladaptive tendencies and cope with unexpected situations [80]. On the other hand, we add new values to the research topic by integrating the principles of stakeholder theory and resource-based theory to explore how strong stakeholder relations contribute to organizational resilience [26,80,81]. Prior resilience research concludes that organizations are more likely to be resilient as they create the continuing ability to use internal and external resources to resolve issues [13,47]. In this line of enquiry, Ortiz-de-Mandojana and Bansal [80] believe that resilience is fostered through flexible resources, such as committed workers and corporate reputation. Gittell, et al. [82] consider relational reserves, financial reserves and viable business models as sources of resilience. These studies, however, construct the logic based on specific resources while neglecting the integration of stakeholders which indeed generate and considerably determine the acquisition of such resources. We connect stakeholder-related values generated by CSR engagement and emphasize the meaning of such values as firms’ competitive advantages, the notions which are manifested in stakeholder theory and resource-based view, thereby contributing a conceptualization of CSR’s effect during a systematic crisis, which is fragmented and incoherent in the literature.

In terms of the conceptualization and measurement of firm resilience, we employ a two-dimension, comprehensive concept instead of merely investigating the variation in stock price as an indicator of firm immunity against the pandemic. The use of a one-dimension concept in prior studies goes through two phases: first comes reliability, then followed by adaptability. In the 1980s, academic interest focused on internal organizational reliability, for instance, Perrow [22] antecedently stressed reliability, which embraces the level of operational safety. Further research on highly reliable organizations tries to explore how these organizations find ways to address challenging conditions and problems [23,24,25]. Since the event of 9/11 2001, terrorist attacks in the US had profound impacts on resilience research, ending the predominant concern with reliability and shifting the attention to adaptability. Scholars pay attention to coping mechanisms and response strategies under conditions of great environmental uncertainty [47,82,83,84]. However, recent studies by DesJardine, Bansal and Yang [26], Buyl, Boone and Wade [27] highlight the need to have an integrated and comprehensive framework of resilience. Accordingly, organizational resilience is distinguished by two dimensions, namely stability and flexibility, which indeed synthesize the characteristics implied in reliability and adaptability in the previous literature. We employ this framework and empirically investigate the influence of CSR on the two dimensions, thereby constituting a significant addition to the resilience research. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic, given its unprecedented widespread scope and devastating severity, is an ideal context to examine the resilience shown by firms. Worldwide systematic shocks are rare, which is why we seize the hit by the COVID-19 crisis to update the resilience measurement and findings.

6.1. Managerial Implications

The COVID-19 pandemic is still on-going, and firms are fighting to adapt themselves to the new normal. How to deter the impact of the pandemic and survive thus is a critical question for managers, investors and regulators. Based on the theory developed and empirical evidence obtained, our research generates several implications that could be employed in the practice of management as well as government regulation.

For managers, they can have a clearer understanding of “where” to invest to develop an appropriate response to crisis and build resilience [85]. Given the potential help by CSR, firms may want to actively disclose their profile of CSR activities and make it noticeable and salient in the company profile if possible. Particularly in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, it becomes clearer than ever that various participants in the economy are highly interdependent when facing the common pandemic. Furthermore, more than ever, the business sector is expected by society and the government to stand on the same side with them and join hands in fighting the disaster. Socially responsible behaviors and activities by business sector would draw attention and be appreciated more than it was back in the old normal. Confirming themselves with the long history as a responsible and ethical corporate identity could help firms to gather support from important groups, thereby strengthening resilience capability.

Our findings would help restore investor confidence in high CSR firms. This is because firms with better CSR performance in the past could absorb exogenous disturbances and bounce back more effectively than their counterparts. These findings reaffirm that values generated by CSR are long-term and sustainable. Based on event system theory, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic created a strong panic because it was highly novel, disruptive and critical [86]. In this case, the confidence and support from investors means more than ever.

Further, investors, governments and regulators should pay close attention to low-CSR investment firms, which are more likely to experience larger severity of loss and lower probability of recovery after the adverse shock. Especially, governments and regulators may want to care for to such firms when offering supports for corporate sector out of the crisis.

6.2. Limitation and Suggestions for Future Research

In spite of the contributions, our research is subject to several limitations. First, although we employ the principle of stakeholder and resource-based theories to theoretically explain the mechanisms through which CSR engagement could help to strengthen firm resilience, our research could not empirically examine the mechanism of the impact of CSR on organizational resilience. Due to the unavailability of archival sources of data, we cannot obtain sufficient data to empirically test the mediating role of the resources generated from enhanced stakeholder relationships in the hypothesized mechanisms. Studies using such datasets are dominated by US samples while we are interested in a Chinese sample in this study. Unfortunately, readily and publicly available equivalents on large sample sizes do not exist in China, nor are reliable and extensive firm-level data. We encourage future scholars to conduct an in-depth investigation involving moderating and mediating factors surrounding the relationship when the necessary data become more available. The second limitation is that the measurement of organizational resilience may limit the generalizability of our findings. Due to the unavailability of data, the observation time window is 142 days which is pretty short. During our observation period, some enterprises did not reach the lowest closing stock price, and some enterprises did not finish the bounce back. Although we use a special research method to remedy this defect, it could cause a certain degree of bias in our research. However, the best way to solve this problem is to extend the observation window, which will make the research less time-efficient. Future studies could consider replicating the research with a wider time window later on when the crisis has finished. Besides, despite the fact that critics of the efficient-market hypothesis accept the idea that stock prices reflect all relevant information about the firm, the gauge of resilience exclusively relies on stock price, which may reflect certain deviation. Future studies could examine different ways of operationalizing organizational resilience, such as long-term sales or different types of stock price.

Third, our findings may be subject to the influence of China’s unique institutional and cultural environments because the data are obtained in one single country. For instance, ownership structure is defined in our research as state-owned firms and other firms, which is quite typical of Chinese corporate guidelines, so the research of ownership structure may be more pervasive in China than in other economies. Although our selection of context to some extent facilitates the investigation of COVID-19 effects as highlighted earlier, future research may need to be cautious when generalizing our findings across other national contexts. Sampling the data set with a wider range of geographic regions with different levels of economic development could help to overcome the limitation.

Author Contributions

Methodology, software and writing—original draft preparation W.H.; study design, supervision and funding acquisition, S.C.; conceptualization, project administration and writing—review and editing, L.T.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant no.71672127 and grant no. 71941023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brown, R.; Rocha, A. Entrepreneurial uncertainty during the Covid-19 crisis: Mapping the temporal dynamics of entrepreneurial finance. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2020, 14, e00174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaccini, M.; Saccani, N.; Kowalkowski, C.; Paiola, M.; Adrodegari, F. Navigating disruptive crises through service-led growth: The impact of COVID-19 on Italian manufacturing firms. Ind. Market. Manag. 2020, 88, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M.; Stanske, S.; Lieberman, M. Strategic responses to crisis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, V7–V18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabia, C.; Alsafib, Z.; O’Neilla, N.; Khanb, M.; Kerwanc, A.; Al-Jabirc, A.; Iosifidisa, C.; Aghad, R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int. J. Surg. 2020, 76, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golan, M.S.; Laura, H.J.; Igor, L. Trends and applications of resilience analytics in supply chain modeling: Systematic literature review in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Environ. Syst Decis 2020, 40, 222–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema-Fox, A.; Laperla, B.R.; Serafeim, G.; Wang, H. Corporate Resilience and Response During COVID-19. Harvard Business School Accounting & Management Unit SSRN 3578167. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3578167 (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Yonggui, W.; Aoran, H.; Xia, L.; Jia, G. Marketing innovations during a global crisis: A study of China firms’ response to COVID-19. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 214–220. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Rangarajan, D.; Paesbrugghe, B. Increasing resilience by creating an adaptive salesforce. Ind. Market. Manag. 2020, 88, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, J.M. COVID, resilience, and the built environment. Environ. Syst Decis. 2020, 40, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L.; Pritchard, L. Resilience and the Behavior of Large-Scale Systems; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Duchek, S. Organizational resilience: A capability-based conceptualization. Bus. Res. 2019, 13, 215–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; van Eeten, M.J.G. The Resilient Organization—A critical appraisal. Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K. Resilience in business and management research: A review of influential publications and a research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmer, W.A.; Shawnee, K.V.; Roger, C. Engendering resilience in small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): A case study of Demmer Corporation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5395–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, A.; Umit, B. Change process: A key enabler for building resilient SMEs. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5601–5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What We Know and Don’t Know About Corporate Social Responsibility A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Gibson, C.; Zander, U. Editors’ Comments: Is Research on Corporate Social Responsibility Undertheorized? Acad. Manag. Rev. 2020, 45, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebble, J.F. Toward a Comprehensive Model of Stakeholder Management. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2005, 110, 407–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, S.; Maklan, S.; French, P. Corporate Social Responsibility: Exploring Stakeholder Relationships and Programme Reporting Across Leading FTSE Companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.P.; Guay, T. Corporate Social Responsibility, Public Policy and NGO Activism in Europe and the United States: An Institutional-Stakeholder Perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrow, C. Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies, Basic Books; Princeton University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Rochlin, G.I. Safe operation as a social construct. Ergonomics 1999, 42, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, K.M. High reliability organizations (HROs). Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2011, 25, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Obstfeld, D. Organizing for high reliability: Processes of collective mindfulness. Res. Organ. Behav. 1999, 3, 81–123. [Google Scholar]

- DesJardine, M.; Bansal, P.; Yang, Y. Bouncing back: Building resilience through social and environmental practices in the context of the 2008 global financial crisis. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1434–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyl, T.; Boone, C.; Wade, J.B. CEO narcissism, risk-taking, and resilience: An empirical analysis in US commercial banks. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1372–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragoncorrea, J.A.; Sharma, S. A Contingent Resource-Based View of Proactive Corporate Environmental Strategy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M. Stakeholder influence capacity and the variability of financial returns to corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 794–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caligiuri, P.; Mencin, A.; Jiang, K. Win–Win–Win: The Influence of Company-Sponsored Volunteerism Programs on Employees, NGOs, and Business Units. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 825–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Song, H.J.; Lee, H.M.; Lee, S.; Bernhard, B.J. The impact of CSR on casino employees’ organizational trust, job satisfaction, and customer orientation: An empirical examination of responsible gambling strategies. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.P.; Lyau, N.M.; Tsai, Y.H.; Chen, W.Y.; Chiu, C.K. Modeling Corporate Citizenship and Its Relationship with Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics. 2010, 95, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, K.; Hattrup, K.; Spiess, S.O.; Lin-Hi, N. The effects of corporate social responsibility on employees’ affective commitment: A cross-cultural investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 1186–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Shao, R.; Thornton, M.A.; Skarlicki, D.P. Applicants’ and Employees’ Reactions to Corporate Social Responsibility: The Moderating Effects of First-Party Justice Perceptions and Moral Identity. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 895–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, R.E.; Corlett, S.; Morris, R. Exploring Employee Engagement with (Corporate) Social Responsibility: A Social Exchange Perspective on Organisational Participation. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrikat, J.; Guenther, E.; Hoppe, H. Making sense of conflicting empirical findings: A meta-analytic review of the relationship between corporate environmental and financial performance. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M.E. A Stakeholder Framework for Analyzing and Evaluating Corporate Social Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, C.A.C. Corporate Stakeholders and Corporate Finance. Finan. Manag. 1987, 16, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pittman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Bradley, R.A.; Donna, J.W. Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Is the resource-based ‘view’ a useful perspective for strategic management research?Yes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, J.T.; Pandian, J.R. The resource-based view within the conversation of strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1992, 13, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, D.M. The market reaction to social responsibility disclosures: The case of the Sullivan principles signings. Account. Organ. Soc. 1990, 15, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, K.M.; Vogus, T.J. Organizing for resilience. In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline; Cameron, K.S., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Managing the Unexpected; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2001; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E. The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: The Mann Gulch disaster. Adm. Sci. Q. 1993, 38, 628–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.; Wilson, D.C.; Branicki, L.; Sullivan-Taylor, B.; Wilson, A.D. Extreme events, organizations and the politics of strategic decision making. Account. Audit Account. J. 2010, 23, 699–721. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan-Taylor, B.; Wilson, D. Managing the Threat of Terrorism in British Travel and Leisure Organizations. Organ. Stud. 2009, 30, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggemann, S.; Williams, M.; Kro, G. Building in sustainability, social responsibility and value co-creation. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2014, 29, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhiraja, S.; Yadav, S. Employer Branding and Employee-Emotional Bonding—The CSR Way to Sustainable HRM; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, M.; Kahn, B.; Sharples, C. Sustainable Investing: Establishing Long-Term Value and Performance. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.K.; Marcus, A.A. Rules versus discretion: The productivity consequences of flexible regulation. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 170–179. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, M.V.; Fouts, P.A. A Resource-Based Perspective on Corporate Environmental Performance and Profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 534–559. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.; Shanley, M. What’s in a Name? Reputation Building and Corporate Strategy. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 233–258. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Satisfaction, and Market Value. J. Marketing 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Del Bosque, I.R. CSR and customer loyalty: The roles of trust, customer identification with the company and satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Greening, D.W.; Turban, D.B. Corporate Social Performance as a Competitive Advantage in Attracting a Quality Workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Greening, D.W. Corporate Social Performance And Organizational Attractiveness To Prospective Employees. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 658–672. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse, K.; Verbeke, A. Proactive environmental strategies: A stakeholder management perspective. Strateg. Manag. 2003, 24, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Dowell, G. A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm: Fifteen Years After. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Alvarez, I.; Prado-Lorenzo, J.M.; Garcia-Sanchez, I.M. Corporate social responsibility and innovation: A resource-based theory. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 1709–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Vredenburg, H. Proactive corporate environmental strategy and the development of competitively valuable capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 729–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.D. Adapting to Environmental Jolts. Adm. Sci. Q. 1982, 27, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, D.; Kreutzer, M.; Lechner, C. Resolving the Paradox of Interdependency and Strategic Renewal in Activity Systems. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 210–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K. Positive organizing and organizational tragedy. In In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline; Cameron, K., Dutton, J., Quinn, R., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 66–80. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, M.; Xu, R.; Liao, X.; Zhang, S. Do CSR ratings converge in China? A comparison between RKS and Hexun scores. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, J. Managerial Humanistic Attention and CSR: Do Firm Characteristics Matter? Sustainability 2018, 10, 4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, M.; Zhang, M. Chinese Financial Market Investors Attitudes toward Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from Mergers and Acquisitions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wong, T.J.; Xia, L. State ownership, the institutional environment, and auditor choice: Evidence from China. J. Acc. Econ. 2008, 46, 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qian, C. Corporate Philanthropy and Financial Performance: The Roles of Social Expectations and Political Access. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 1159–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D.R. Regression Models and Life-Tables (With Discussion). J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Stat. Methodol.) 1971, 34, 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D.R. Partial Likelihood. Biometrika 1975, 62, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Levine, R.; Lin, C.; Xie, W. Corporate Immunity to the COVID-19 Pandemic; 0898-2937; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, A.; Yrjo, K.; Shuai, Y.; Chendi, Z. Resiliency of Environmental and Social Stocks: An Analysis of the Exogenous COVID-19 Market Crash. Rev. Corp. Financ. Stud. 2020, 9, 593–621. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N.; Bansal, P. The long-term benefits of organizational resilience through sustainable business practices. Strateg. Manag. 2016, 37, 1615–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C.; Ioannou, I. To save or to invest? Strategic management during the financial crisis. Strateg. Manag. Financ. Crisis 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittell, J.H.; Cameron, K.; Lim, S.; Rivas, V. Relationships, layoffs, and organizational resilience: Airline industry responses to September 11. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2006, 42, 300–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutu, D.L. How Resilience Works. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 46–50, 52, 55 passim. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hamel, G.; Vlikangas, L. The quest for resilience. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2003, 81, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, H.S.; Poolton, J.; Sharifi, H. The role of agile strategic capabilities in achieving resilience in manufacturing-based small companies. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5469–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, L.A.; Reeves, S.; Porr, W.B.; Ployhart, R.E. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on job search behavior: An event transition perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).